Abstract

Background

Associations between thyroid function and hepatic steatosis defined by enzymatic and sonographic criteria are largely unknown in the general population. Thus, the aim of the present study was to investigate the association between thyroid function tests and sonographic as well as enzymatic criteria of liver status in a large population-based study, the Study of Health in Germany (SHIP).

Methods

Data from 3661 SHIP participants without a self-reported history of thyroid or liver disease were analyzed. Hepatic steatosis was defined as the presence of a hyperechogenic ultrasound pattern of the liver and increased serum alanine transferase concentrations. Serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), free triiodothyronine (FT3), and free thyroxine (FT4) concentrations were associated with hepatic steatosis using multinomial regression models adjusted for sex, age, physical activity, alcohol consumption, waist circumference, and food intake pattern.

Results

We detected no consistent association of serum TSH and FT3 concentrations with hepatic steatosis. In contrast, serum FT4 concentrations were inversely associated with hepatic steatosis in men (odds ratio (OR)=0.04 [95% confidence interval (CI)=0.01; 0.17]) and women (OR=0.06 [95% CI=0.01; 0.42]).

Conclusions

Results from the present cross-sectional study suggest that low FT4 concentrations are associated with hepatic steatosis. Longitudinal and intervention studies are warranted to investigate whether hypothyroidism increases the risk of hepatic steatosis or vice versa.

Introduction

Thyroid hormones play an important role in hepatic lipid homeostasis (1) through increased expression of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptors on the hepatocytes (2) and the activation of lipid-lowering liver transaminases (3), which result in lower serum LDL concentrations. On the other hand, the liver metabolizes thyroid hormones and thereby influences the regulation of their systematic endocrine effects (4).

Several previous studies investigated thyroid function tests in patients with liver cirrhosis (5–9), but only three studies addressed the association between thyroid function tests and hepatic steatosis (10–12). One study that was conducted in inpatients using a matched case–control design demonstrated a twofold higher risk of hypothyroidism in patients with hepatic steatosis compared with controls (11). Another study among 10,292 outpatients (12) investigated associations of serum thyrotropin (thyroid-stimulating hormone; TSH) and free thyroxine (FT4) concentrations with serum γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) concentrations. In that study (12), serum TSH concentrations were positively associated with liver enzyme concentrations, while serum FT4 concentrations were inversely related with liver enzyme concentrations. Finally, a small case–control study found significantly lower concentrations of FT4, but not TSH, in men with alcoholic fatty liver disease (10).

The results of these studies (10–12) indicate that hypothyroidism might be related to hepatic steatosis. This seems to be biologically plausible, as overt hypothyroidism is associated with visceral obesity (13,14), metabolic syndrome (15), insulin resistance (16), and lipid peroxidation (17), all of which are closely related to hepatic steatosis. Moreover, evidence from population-based studies (18–21) suggests that sonographic and laboratory markers of hepatic steatosis are associated with the risk of atherosclerotic endpoints, and are therefore in line with the increased cardiovascular risk in hypothyroidism (22–24).

Previous studies are limited by selected populations (10–12), small sample sizes (10,11), and potential residual confounding through lacking information on influential medications (e.g., thyroid hormone replacement or antithyroid drugs), lifestyle characteristics (e.g., alcohol consumption), and obesity status among the study participants (10–12). In addition, previous reports were partly based on increased transaminase concentrations to indicate fatty liver (12), but transaminase concentrations might be increased due to various reasons not necessarily related to hepatic steatosis (25). In contrast, the diagnosis of hepatic steatosis based on ultrasound and increased transaminase concentrations is much more specific and sensitive than a diagnosis based solely on liver enzymes (26).

To overcome the limitations of previous research, the aim of the present study was to investigate the association between thyroid function tests and hepatic steatosis identified by increased ALT concentrations and liver ultrasound. For this, we used data from a large-scale population-based study, the Study of Health in Germany (SHIP).

Materials and Methods

Study population

SHIP is a population-based study in West Pomerania, a region in Northeast Germany. Details on study design have been published previously (27,28). In brief, from the 212,157 inhabitants living in the area, a representative random sample of 7008 subjects aged 20 to 79 years was selected using population registries where all German inhabitants are registered. Only individuals with German citizenship and main residency in the study area were included. The net sample (without migrated or deceased persons) comprised 6267 eligible subjects, whereof 4308 finally participated (response 68.8%). All participants gave written informed consent. The study conformed to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in an a priori approval by the local Ethics Committee of the University of Greifswald.

There were 647 subjects (452 women) excluded due to (overlaps exist) known self-reported thyroid disease (n=349), current thyroid-related medication according to the anatomical-therapeutical-chemical code H03 (n=285), positive hepatitis antibodies or reported history of liver cirrhosis (n=37), and missing data in any of the considered variables (n=131). The final study population for the present analysis comprised 3661 subjects (1741 women).

Measurements

All participants underwent an extensive standardized medical examination including the collection of blood samples. Liver ultrasound was performed by trained physicians using a 5 MHz transducer and a high-resolution instrument (Vingmed VST Gateway, Santa Clara, CA). The sonographers were unaware of the participant's clinical and laboratory characteristics. In SHIP, ultrasound examinations and readings have strict quality standards (29,30). A hyperechogenic liver pattern was defined as the presence of a bright pattern with evident density differences between hepatic and renal parenchyma (21,31,32).

For laboratory examinations, nonfasting blood samples were drawn from the cubital vein in the supine position. The laboratory quarterly takes part in the official national German external proficiency testing programs. In addition, internal quality controls were analyzed daily. Serum ALT, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and GGT concentrations were measured photometrically (Hitachi 704; Roche, Mannheim, Germany). ALT, AST, and GGT concentrations were expressed as μmol/(L·s), which corresponds to (μmol/[L·s])×60=IU/L. For ALT, concentrations exceeding the sex-specific 75th percentile were termed as increased ALT—0.69 μmol/(L·s) in men and 0.41 μmol/(L·s) in women. Hepatic steatosis was defined as a hyperechogenic liver pattern in ultrasound and increased ALT concentrations (33,34). Concentrations of TSH, free triiodothyronine (FT3), and FT4 were analyzed by immunochemiluminescent procedures (FT3, LUMItest, Brahms, Berlin, Germany; TSH and FT4, LIA-mat, Byk Sangtec Diagnostica GmbH, Frankfurt, Germany). All assays were performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The functional sensitivity of the TSH assay was 0.03 mIU/L. Hyper- and hypothyroidism as well as their overt and subclinical forms were defined using reference limits established in the study region (35). Hyperthyroidism was defined by decreased serum TSH concentrations; hypothyroidism was defined by increased serum TSH concentrations. Subclinical hyper- or hypothyroidism was defined by decreased or increased serum TSH concentrations and FT4 and FT3 concentrations being in the reference range. Overt hyper- or hypothyroidism was defined by decreased or increased serum TSH concentrations and increased or decreased FT3 or FT4 concentrations.

The anthropometric measures included waist circumference, measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using an inelastic tape midway between the lower rib margin and the iliac crest in the horizontal plane, with the subject standing comfortably with weight distributed evenly on both feet. Lifestyle factors included physical activity, food intake pattern, and alcohol consumption. Subjects who participated in physical training during summer or winter for at least 1 hour a week were classified as being physically active. Alcohol consumption was evaluated as beverage-specific alcohol consumption (beer, wine, and distilled spirits) on the last weekend and last weekday preceding the examination, and the mean daily alcohol consumption was calculated using beverage-specific pure ethanol volume proportions (36). Food intake pattern was selected from a validated food frequency questionnaire. The classifications were summarized to a dietary pattern score for each subject (37). Gender-specific tertiles of this score reflected the food quality: lower tertile, unfavorable dietary pattern (<12 for men, <14 for women); medium tertile, intermediate dietary pattern (12 to 14 for men, 14 to 16 for women); and upper tertile, favorable dietary pattern (>14 for men, >16 for women).

Statistical analysis

Selected baseline demographic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics were compared by sex using χ2 test (qualitative data) or Mann–Whitney U-test (quantitative data). Serum TSH, FT3, and FT4 concentrations were associated with liver enzymes and hyperechogenic liver pattern by multivariable regression models adjusted for age, physical activity, alcohol consumption, waist circumference, and food intake pattern. For categorical outcomes, multinomial logistic regression models were applied. To weaken the impact of outliers in the exposure variable on the associations investigated, TSH, FT3, and FT4 concentrations were power-transformed before they were used in regression analyses (38). Since the interaction term between serum TSH concentrations and sex was significantly associated to the outcome variables, all analyses were done stratified for men and women. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant in all calculations. All statistical analyses were performed by Stata 11.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX).

Results

Characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. Compared with women, men were older, had a higher waist circumference, and consumed more alcohol. Men also had significantly higher concentrations of liver enzymes (ALT, AST, and GGT), FT3, and FT4, but lower serum TSH concentrations. Prevalence of a hyperechogenic liver pattern was nearly twice as high in men than in women. Similarly, we found a higher prevalence of hepatic steatosis in men (16.3%) compared with women (11.3%).

Table 1.

Selected Baseline Characteristics Stratified by Sex

| Men (n=1920) | Women (n=1741) | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 50.5±16.6 | 48.1±16.1 | <0.001 |

| ALT (μmol/[L·s]) | 0.58±0.37 | 0.36±0.21 | <0.001 |

| AST (μmol/[L·s]) | 0.42±0.27 | 0.32±0.15 | <0.001 |

| GGT (μmol/[L·s]) | 0.81±1.73 | 0.37±0.53 | <0.001 |

| TSH (mU/L) | 0.77±0.86 | 0.99±3.12 | <0.001 |

| FT3 (pmol/L) | 5.31±0.89 | 5.17±0.83 | <0.001 |

| FT4 (pmol/L) | 13.11±3.07 | 12.43±4.49 | <0.001 |

| Hyperthyroidism | 156 (8.1%) | 123 (7.1%) | 0.231 |

| Subclinical | 140 (7.3%) | 109 (6.3%) | 0.217 |

| Overt | 16 (0.8%) | 14 (0.8%) | 0.923 |

| Hypothyroidism | 34 (1.8%) | 66 (3.8%) | <0.001 |

| Subclinical | 29 (1.5%) | 50 (2.9%) | 0.005 |

| Overt | 5 (0.3%) | 16 (0.9%) | 0.008 |

| Hyperechogenic liver pattern | 724 (37.7%) | 363 (20.8%) | <0.001 |

| Hepatic steatosis | <0.001 | ||

| US− & ALT<75th percentile | 1014 (52.8%) | 1107 (63.6%) | |

| US− & ALT>75th percentile | 182 (9.5%) | 271 (15.6%) | |

| US+ & ALT<75th percentile | 412 (21.5%) | 167 (9.6%) | |

| US+ & ALT>75th percentile | 312 (16.3%) | 196 (11.3%) | |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 95.4±11.7 | 82.5±13.1 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption (g/day) | 19.8±23.1 | 5.5±9.2 | <0.001 |

| Physically active | 803 (41.8%) | 772 (44.3%) | 0.124 |

| Food intake pattern | 0.999 | ||

| Unfavorable | 683 (35.6%) | 619 (35.6%) | |

| Intermediate | 448 (23.3%) | 406 (23.3%) | |

| Optimal | 789 (41.1%) | 716 (41.1%) |

Data are absolute numbers (percentages) or means±standard deviation.

p-Values were calculated with χ2 test for categorical and Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables.

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; FT3, free triiodothyronine; FT4, free thyroxine; US+, hyperechogenic liver ultrasound pattern; US−, normoechogenic liver ultrasound pattern.

Table 2 shows the results of the multinomial logistic regression analyses, which revealed a borderline significant association between serum TSH concentrations and hepatic steatosis in men but not in women. No association was detected between serum TSH concentrations and ALT concentrations within the reference range combined with a hyperechogenic liver pattern in men and women. Further, there were no significant interaction terms between serum TSH concentrations and any of the confounders, which were significantly associated with hepatic steatosis.

Table 2.

Association Between Serum Thyroid Hormone Concentrations and Hepatic Steatosis in Men and Women

| |

Men (n=1920) |

Women (n=1741) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | OR [95% CI] | p-Value | OR [95% CI] | p-Value |

| Power-transformed TSH | ||||

| US−ALT− | REF | REF | ||

| US−ALT+ | 3.15 [0.24; 41.92] | 0.384 | 2.69 [0.61; 11.88] | 0.192 |

| US+ALT− | 1.10 [0.13; 9.04] | 0.928 | 0.47 [0.05; 4.46] | 0.509 |

| US+ALT+ | 7.00 [0.86; 56.90] | 0.069 | 1.64 [0.27; 10.08] | 0.594 |

| Power-transformed FT4 | ||||

| US−ALT− | REF | REF | ||

| US−ALT+ | 0.66 [0.12; 3.52] | 0.629 | 1.38 [0.35; 5.44] | 0.644 |

| US+ALT− | 0.20 [0.06; 0.67] | 0.009 | 0.04 [0.01; 0.30] | 0.001 |

| US+ALT+ | 0.04 [0.01; 0.17] | <0.001 | 0.06 [0.01; 0.42] | 0.004 |

| Power-transformed FT3 | ||||

| US−ALT− | REF | REF | ||

| US−ALT+ | 0.87 [0.24; 3.08] | 0.827 | 0.62 [0.22; 1.75] | 0.368 |

| US+ALT− | 2.60 [1.03; 6.56] | 0.043 | 0.45 [0.12; 1.78] | 0.258 |

| US+ALT+ | 1.30 [0.43; 3.90] | 0.640 | 1.19 [0.32; 4.44] | 0.791 |

OR: outcome was analyzed by multinomial logistic regression adjusted for age, physical activity, alcohol consumption, waist circumference, and food intake pattern.

ALT+, ALT ≥sex-specific 75th percentile; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

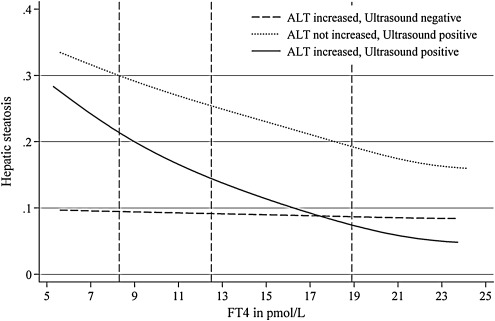

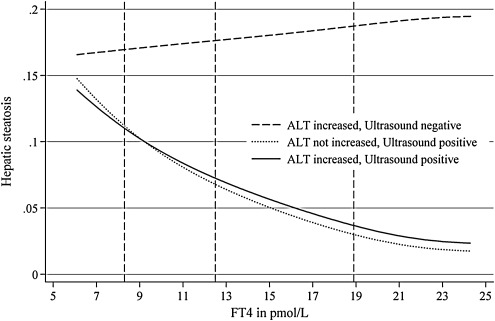

In both men and women, FT4 concentrations were significantly associated with a hepatic steatosis (Table 2; Figs. 1 and 2). The median of the serum FT4 concentration distribution, lower, and upper reference limits established in the study region (35) are provided in Figures 1 and 2. The graphs indicate the probability for the outcome at a specific serum FT4 level. For example, the probability for the combined presence of ALT concentrations ≥75th percentile and a hyperechogenic liver pattern decreases from 22% at a serum FT4 level of 8.3 pmol/L to 8% at a serum FT4 level of 18.9 pmol/L. Results did not differ significantly when additionally adjusted for serum TSH concentrations.

FIG. 1.

Probability for hepatic steatosis at different serum-free thyroxine (FT4) concentrations in men. Vertical dashed lines represent the lower reference limit (8.3 mIU/L), the median of the serum FT4 level distribution (11.8 mIU/L), and the upper reference limit (18.9 mIU/L). ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

FIG. 2.

Probability for hepatic steatosis at different serum FT4 concentrations in women. Vertical dashed lines represent the lower reference limit (8.3 mIU/L), the median of the serum FT4 level distribution (11.8 mIU/L), and the upper reference limit (18.9 mIU/L).

FT3 concentrations were not associated with diagnostic markers of hepatic steatosis with one exception. In men FT3 concentrations were positively associated with a hyperechogenic liver pattern in combination with normal ALT (Table 2).

For sensitivity analysis we categorized serum TSH concentrations according to hyper- and hypothyroidism. We detected no association between hyper- or hypothyroidism and hepatic steatosis in men or women (Table 3). Analyses without adjustment for waist circumference revealed a significant association between hypothyroidism and hepatic steatosis in women (odds ratio (OR)=2.23 [95% confidence interval (CI)=1.11; 4.46]) but not in men (OR=1.89 [95% CI=0.80; 4.53]).

Table 3.

Association Between Hyper- and Hypothyroidism and Hepatic Steatosis in Men and Women

| |

Men (n=1920) |

Women (n=1741) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | OR [95% CI] | p-Value | OR [95% CI] | p-Value |

| Hyperthyroidism | ||||

| US−ALT− | REF | REF | ||

| US−ALT+ | 0.66 [0.29; 1.50] | 0.323 | 1.06 [0.62; 1.79] | 0.838 |

| US+ALT− | 0.82 [0.54; 1.25] | 0.364 | 0.79 [0.42; 1.48] | 0.463 |

| US+ALT+ | 0.73 [0.41; 1.29] | 0.283 | 0.70 [0.36; 1.36] | 0.293 |

| Hypothyroidism | ||||

| US−ALT− | REF | REF | ||

| US−ALT+ | 1.41 [0.48; 4.15] | 0.533 | 1.36 [0.69; 2.67] | 0.370 |

| US+ALT− | 0.75 [0.24; 2.39] | 0.629 | 0.82 [0.31; 2.17] | 0.695 |

| US+ALT+ | 2.18 [0.84; 5.63] | 0.109 | 1.30 [0.59; 2.86] | 0.510 |

OR: outcome was analyzed by multinomial logistic regression adjusted for age, physical activity, alcohol consumption, waist circumference, and food intake pattern.

Hyperthyroidism, TSH≤0.25 mIU/L; hypothyroidism, TSH>2.12 mIU/L.

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate whether there is an association between thyroid function tests and hepatic steatosis using a population-based design. We found an inverse association between serum FT4 concentrations and hepatic steatosis, whereas serum TSH and FT3 concentrations were not consistently associated with hepatic steatosis after adjustment for sex, age, physical activity, alcohol consumption, waist circumference, and food intake.

Our results partly agree with those from Targher et al. (12), who reported positive or negative relations of serum TSH or FT4 concentrations with serum ALT and GGT concentrations. In our study there was only a significant inverse association between FT4 concentrations and hepatic steatosis. Differences between the study of Targher et al. (12) and our investigation might have resulted from lack of consideration of major confounders and mediators, such as waist circumference, alcohol consumption, and food intake pattern, in the latter study (12). Further, the study by Targher et al. (12) was conducted in inpatients with possible selection bias of more severe forms of thyroid, liver, and comorbid conditions in the analytical sample. In contrast, our study population was recruited population-based where subjects with preclinical states might be well presented. Moreover, the outcome in the latter study (12) was only defined using serum transaminase concentrations, whereas hepatic steatosis was more sensitively defined using both sonographic and laboratory criteria in our study. Serum ALT concentrations are not only a marker for liver disease but also for general cell death. Thus, the reported association between serum TSH and ALT concentrations might be referred to a relationship of serum TSH concentrations with general cell death but not necessarily with hepatic steatosis.

Liangpunsakul and Chalasani (11) reported a higher prevalence of hypothyroidism in patients with a hepatic steatosis than in controls. Our study did not confirm this finding, since hypothyroidism defined by increased serum TSH levels was not significantly associated with hepatic steatosis. The results from the latter study (11), however, might not be comparable to those from our study. Their study population was recruited from inpatients (11) and, in contrast to our study, hypothyroidism was defined according to medication and previous diagnosis of hypothyroidism. Given the clinical setting of the other study, the frequency of participants with overt hypothyroidism in the group of hypothyroid individuals was higher than in our population-based study. This suggestion is further supported by the fact that serum FT4 but not serum TSH levels were significantly associated with hepatic steatosis in our study. Thus, overt but not subclinical hypothyroidism might be associated with hepatic steatosis. In our study population it was not possible to investigate the association between overt hypothyroidism and hepatic steatosis because the numbers were inadequately low.

Green et al. (10) reported decreased FT4 and T4 concentrations but normal FT3 and T3 concentrations in patients with a fatty liver disease, whereas FT4 concentrations were normal and FT3 concentrations decreased in end-stage liver disease. Our study not only confirms the results from that study, but extends current knowledge by providing evidence that an association between FT4 and hepatic steatosis is not only present in clinically well-defined patients but also in the general population.

There are explanations, which may substantiate the relationship between thyroid function tests and hepatic steatosis. First, the association between thyroid function and hepatic steatosis might be related to the possible effect of hypothyroidism on the development of obesity (13,14). Adipokines like leptin, secreted by visceral adipose tissue, stimulate the hypothalamicpituitary-thyroid axis to increase TSH secretion (38,39). In our analysis, hypothyroidism was associated with hepatic steatosis in women but not in men without adjustment for waist circumference. Thus, mediation by obesity might play a role in the association between hypothyroidism and hepatic steatosis even though we detected no consistent association between serum TSH concentrations and hepatic steatosis.

Second, patients with hypothyroidism have not only an increased risk of hyperlipidemia (39) but also exhibit increased fatty acid oxidation and hepatic output of triglycerides. Consequently, hypothyroid patients might be prone to altered lipid peroxidation (17), which is one of the leading causes of liver cell damage (40). Third, decreased thyroid function is associated with insulin resistance, which appears to be a hallmark of hepatic steatosis (16), as well as features of the metabolic syndrome (15), including visceral obesity, glucose intolerance, hypertriglyceridemia, hypertension, and low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (41). Thyroid hormones have pleiotropic effects on energy homeostasis (14,42), lipid and glucose metabolism (43–45), and blood pressure (46), relating thyroid hormone concentrations with parameters of the metabolic syndrome.

On the other hand, the missing association between serum TSH concentrations and hepatic steatosis along with the inverse association between serum FT4 concentrations and hepatic steatosis in our study might argue for a relationship between hepatic steatosis and decreased thyroid function tests in the alternative direction. In men, ∼80% of T3 is produced from T4 by conversion in liver and kidneys. It is well known that liver fat accumulation influences the metabolism of different hormones. For example, increased 5β-reductase activities (47) result in fewer cortisol/cortison metabolites and an altered negative feedback control of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, which in consequence enhances the adrenocorticotropic hormone–dependent dehydroepiandrosteron sulfate production. The inverse association between serum dehydroepiandrosteron sulfate levels and the risk of hepatic steatosis in young men has been suggested by our group previously (48). Regarding thyroid hormones, the conversion of T4 to T3 might be reduced by stress, starvation, or chronic illness, which may result in the so-called low T3 syndrome or nonthyroidal illness. This phenomenon has been explained by the idea that the body tries to reduce its metabolism to conserve energy. Early studies suggested that some fatty acids are potent inhibitors of extrathyroidal T4 conversion (49). Recently, it has been shown that impaired thyroid hormone action itself may contribute to altered transcriptional changes in human liver, which results in hepatic lipid accumulation and might be associated with insulin resistance in fatty liver (50). Therefore, an increase of fatty acids in hepatic steatosis might inhibit T4 to T3 conversion, which in turn perpetuates fat accumulation in the liver. Thus, the question of causality remains unanswered by our cross-sectional study. Longitudinal and intervention studies to determine the direction of causality are strongly needed in this respect.

In summary, results from the present cross-sectional study suggest that low FT4 concentrations are associated with hepatic steatosis. We detected no consistent association between serum TSH concentrations and hepatic steatosis. Longitudinal and intervention studies are warranted to investigate whether hypothyroidism is causally related to hepatic steatosis or vice versa.

Acknowledgments

SHIP is part of the Community Medicine Net (www.medizin.uni-greifswald.de/cm) of the University of Greifswald, which is funded by grants from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, grant 01ZZ0403); the Ministry for Education, Research, and Cultural Affairs; and the Ministry for Social Affairs of the Federal State of Mecklenburg–West Pomerania. The analyses were further supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG Vo 955/5-2) and the GANI_MED consortium, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. The contributions to data collection made by field workers, study physicians, ultrasound technicians, interviewers, and computer assistants are gratefully acknowledged. Novo Nordisk provided partial grant support for the determination of plasma samples and data analysis.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Malik R. Hodgson H. The relationship between the thyroid gland and the liver. QJM. 2002;95:559–569. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/95.9.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ness GC. Lopez D. Chambers CM. Newsome WP. Cornelius P. Long CA. Harwood HJ., Jr Effects of L-triiodothyronine and the thyromimetic L-94901 on serum lipoprotein levels and hepatic low-density lipoprotein receptor, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase, and apo A-I gene expression. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;56:121–129. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ness GC. Lopez D. Transcriptional regulation of rat hepatic low-density lipoprotein receptor and cholesterol 7 alpha hydroxylase by thyroid hormone. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;323:404–408. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reed L. Pangaro LN. Physiology of the thyroid gland, the liver. In: Becker KL, editor. Principles and Practice of Endocrinology and Metabolism. Vol. Lippincott Co.; Philadelphia: 1995. pp. 285–291. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bianchi GP. Zoli M. Marchesini G. Volta U. Vecchi F. Iervese T. Bonazzi C. Pisi E. Thyroid gland size and function in patients with cirrhosis of the liver. Liver. 1991;11:71–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1991.tb00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faber J. Thomsen HF. Lumholtz IB. Kirkegaard C. Siersbaek-Nielsen K. Friis T. Kinetic studies of thyroxine, 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine, 3,3,5′-triiodothyronine, 3′,5′-diiodothyronine, 3,3′-diiodothyronine, and 3′-monoiodothyronine in patients with liver cirrhosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1981;53:978–984. doi: 10.1210/jcem-53-5-978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guven K. Kelestimur F. Yucesoy M. Thyroid function tests in non-alcoholic cirrhotic patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Eur J Med. 1993;2:83–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.L'Age M. Meinhold H. Wenzel KW. Schleusener H. Relations between serum levels of TSH, TBG, T4, T3, rT3 and various histologically classified chronic liver diseases. J Endocrinol Invest. 1980;3:379–383. doi: 10.1007/BF03349374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oren R. Sikuler E. Wong F. Blendis LM. Halpern Z. The effects of hypothyroidism on liver status of cirrhotic patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;31:162–163. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200009000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green JR. Snitcher EJ. Mowat NA. Ekins RP. Rees LH. Dawson AM. Thyroid function and thyroid regulation in euthyroid men with chronic liver disease: evidence of multiple abnormalities. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1977;7:453–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1977.tb01337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liangpunsakul S. Chalasani N. Is hypothyroidism a risk factor for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;37:340–343. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200310000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Targher G. Montagnana M. Salvagno G. Moghetti P. Zoppini G. Muggeo M. Lippi G. Association between serum TSH, free T4 and serum liver enzyme activities in a large cohort of unselected outpatients. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;68:481–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knudsen N. Laurberg P. Rasmussen LB. Bulow I. Perrild H. Ovesen L. Jorgensen T. Small differences in thyroid function may be important for body mass index and the occurrence of obesity in the population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:4019–4024. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nyrnes A. Jorde R. Sundsfjord J. Serum TSH is positively associated with BMI. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:100–105. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uzunlulu M. Yorulmaz E. Oguz A. Prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism in patients with metabolic syndrome. Endocr J. 2007;54:71–76. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k06-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maratou E. Hadjidakis DJ. Kollias A. Tsegka K. Peppa M. Alevizaki M. Mitrou P. Lambadiari V. Boutati E. Nikzas D. Tountas N. Economopoulos T. Raptis SA. Dimitriadis G. Studies of insulin resistance in patients with clinical and subclinical hypothyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;160:785–790. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sundaram V. Hanna AN. Koneru L. Newman HA. Falko JM. Both hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism enhance low density lipoprotein oxidation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:3421–3424. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.10.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee DH. Jacobs DR., Jr Gross M. Kiefe CI. Roseman J. Lewis CE. Steffes M. Gamma-glutamyltransferase is a predictor of incident diabetes and hypertension: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Clin Chem. 2003;49:1358–1366. doi: 10.1373/49.8.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee DH. Silventoinen K. Hu G. Jacobs DR., Jr Jousilahti P. Sundvall J. Tuomilehto J. Serum gamma-glutamyltransferase predicts non-fatal myocardial infarction and fatal coronary heart disease among 28,838 middle-aged men and women. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2170–2176. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meisinger C. Doring A. Schneider A. Lowel H. Serum gamma-glutamyltransferase is a predictor of incident coronary events in apparently healthy men from the general population. Atherosclerosis. 2006;189:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volzke H. Robinson DM. Kleine V. Deutscher R. Hoffmann W. Ludemann J. Schminke U. Kessler C. John U. Hepatic steatosis is associated with an increased risk of carotid atherosclerosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1848–1853. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i12.1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biondi B. Klein I. Hypothyroidism as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Endocrine. 2004;24:1–13. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:24:1:001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fowler PB. Risk in cardiovascular disease. Subclinical hypothyroidism is risk factor for coronary heart disease. Bmj. 2000;321:175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodondi N. Newman AB. Vittinghoff E. de Rekeneire N. Satterfield S. Harris TB. Bauer DC. Subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of heart failure, other cardiovascular events, and death. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2460–2466. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.21.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis JR. Mohanty SR. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a review and update. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:560–578. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Springer F. Machann J. Claussen CD. Schick F. Schwenzer NF. Liver fat content determined by magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1560–1566. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i13.1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.John U. Greiner B. Hensel E. Lüdemann J. Piek M. Sauer S. Adam C. Born G. Alte D. Greiser E. Haertel U. Hense HW. Haerting J. Willich S. Kessler C. Study of Health In Pomerania (SHIP): a health examination survey in an east German region: objectives and design. Soz Praventivmed. 2001;46:186–194. doi: 10.1007/BF01324255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Volzke H. Ittermann T. Schmidt CO. Dorr M. John U. Wallaschofski H. Stricker BH. Felix SB. Rettig R. Subclinical hyperthyroidism and blood pressure in a population-based prospective cohort study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;161:615–621. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dorr M. Wolff B. Robinson DM. John U. Ludemann J. Meng W. Felix SB. Volzke H. The association of thyroid function with cardiac mass and left ventricular hypertrophy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:673–677. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Volzke H. Alte D. Schmidt CO. Radke D. Lorbeer R. Friedrich N. Aumann N. Lau K. Piontek M. Born G. Havemann C. Ittermann T. Schipf S. Haring R. Baumeister SE. Wallaschofski H. Nauck M. Frick S. Arnold A. Junger M. Mayerle J. Kraft M. Lerch MM. Dorr M. Reffelmann T. Empen K. Felix SB. Obst A. Koch B. Glaser S. Ewert R. Fietze I. Penzel T. Doren M. Rathmann W. Haerting J. Hannemann M. Ropcke J. Schminke U. Jurgens C. Tost F. Rettig R. Kors JA. Ungerer S. Hegenscheid K. Kuhn JP. Kuhn J. Hosten N. Puls R. Henke J. Gloger O. Teumer A. Homuth G. Volker U. Schwahn C. Holtfreter B. Polzer I. Kohlmann T. Grabe HJ. Rosskopf D. Kroemer HK. Kocher T. Biffar R. John U. Hoffmann W. Cohort profile: the study of health in Pomerania. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:294–307. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and the metabolic syndrome. Am J Med Sci. 2005;330:326–335. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200512000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Volzke H. Schwarz S. Baumeister SE. Wallaschofski H. Schwahn C. Grabe HJ. Kohlmann T. John U. Doren M. Menopausal status and hepatic steatosis in a general female population. Gut. 2007;56:594–595. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.115345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haring R. Wallaschofski H. Nauck M. Dorr M. Baumeister SE. Volzke H. Ultrasonographic hepatic steatosis increases prediction of mortality risk from elevated serum gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase levels. Hepatology. 2009;50:1403–1411. doi: 10.1002/hep.23135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lau K. Lorbeer R. Haring R. Schmidt CO. Wallaschofski H. Nauck M. John U. Baumeister SE. Volzke H. The association between fatty liver disease and blood pressure in a population-based prospective longitudinal study. J Hypertens. 2010;28:1829–1835. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833c211b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Volzke H. Alte D. Kohlmann T. Ludemann J. Nauck M. John U. Meng W. Reference intervals of serum thyroid function tests in a previously iodine-deficient area. Thyroid. 2005;15:279–285. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alte D. Ludemann J. Piek M. Adam C. Rose HJ. John U. Distribution and dose response of laboratory markers to alcohol consumption in a general population: results of the study of health in Pomerania (SHIP) J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64:75–82. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winkler G. Schwertner B. Döring A. [Short methods for the characterization of a dietary pattern: use and evaluation of a food-frequency questionnaire] Ernährungsumschau. 1995;42:289–291. (In German.) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Royston P. Sauerbrei W. Multivariable Model–Building: A Pragmatic Approach to Regression Anaylsis based on Fractional Polynomials for Modelling Continuous Variables. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester United Kingdom: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duntas LH. Thyroid disease and lipids. Thyroid. 2002;12:287–293. doi: 10.1089/10507250252949405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poli G. Albano E. Dianzani MU. The role of lipid peroxidation in liver damage. Chem Phys Lipids. 1987;45:117–142. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(87)90063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grundy SM. Metabolic syndrome pandemic. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:629–636. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.151092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krotkiewski M. Thyroid hormones in the pathogenesis and treatment of obesity. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;440:85–98. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01420-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Danese MD. Ladenson PW. Meinert CL. Powe NR. Clinical review 115: effect of thyroxine therapy on serum lipoproteins in patients with mild thyroid failure: a quantitative review of the literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:2993–3001. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.9.6841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kutty KM. Bryant DG. Farid NR. Serum lipids in hypothyroidism—a re-evaluation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1978;46:55–56. doi: 10.1210/jcem-46-1-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Torrance CJ. Devente JE. Jones JP. Dohm GL. Effects of thyroid hormone on GLUT4 glucose transporter gene expression and NIDDM in rats. Endocrinology. 1997;138:1204–1214. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.3.4981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Asvold BO. Bjoro T. Nilsen TI. Vatten LJ. Association between blood pressure and serum thyroid-stimulating hormone concentration within the reference range: a population-based study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:841–845. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Westerbacka J. Yki-Jarvinen H. Vehkavaara S. Hakkinen AM. Andrew R. Wake DJ. Seckl JR. Walker BR. Body fat distribution and cortisol metabolism in healthy men: enhanced 5beta-reductase and lower cortisol/cortisone metabolite ratios in men with fatty liver. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4924–4931. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Volzke H. Aumann N. Krebs A. Nauck M. Steveling A. Lerch MM. Rosskopf D. Wallaschofski H. Hepatic steatosis is associated with low serum testosterone and high serum DHEAS levels in men. Int J Androl. 2010;33:45–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2009.00953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chopra IJ. Huang TS. Beredo A. Solomon DH. Chua Teco GN. Mead JF. Evidence for an inhibitor of extrathyroidal conversion of thyroxine to 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine in sera of patients with nonthyroidal illnesses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;60:666–672. doi: 10.1210/jcem-60-4-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pihlajamaki J. Boes T. Kim EY. Dearie F. Kim BW. Schroeder J. Mun E. Nasser I. Park PJ. Bianco AC. Goldfine AB. Patti ME. Thyroid hormone-related regulation of gene expression in human fatty liver. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3521–3529. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]