Abstract

We report Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi strains with a nonclassical quinolone resistance phenotype (i.e., decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin but with susceptibility to nalidixic acid) associated with a nonsynonymous mutation at codon 464 of the gyrB gene. These strains, not detected by the nalidixic acid disk screening test, can result in fluoroquinolone treatment failure.

Keywords: Salmonella, typhoid fever, ciprofloxacin, treatment failure, gyrB, bacteria, antimicrobial resistance, expedited, dispatch

Typhoid fever caused by Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi (hereafter referred to as Salmonella Typhi) remains a major health problem in the developing world (1). Treatment with appropriate antimicrobial drugs has become hampered by gradual plasmid-mediated resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and cotrimoxazole, particularly in southern and Southeast Asia (2). Consequently, since the early 1990s, fluoroquinolones (such as ofloxacin and ciprofloxacin [Cip]) have been widely used. However, multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhi isolates that are also resistant to nalidixic acid (NalR) (MIC >256 μg/mL) and show decreased susceptibility to Cip (CipDS) (MIC range, 0.125 μg/mL–1 μg/mL) have emerged and become endemic on the Indian subcontinent and in Southeast Asia (3–5). This resistance to quinolones was caused by amino acid substitutions in the quinolone resistance–determining region (QRDR) of the DNA gyrase subunit gyrA, a key target of quinolones. Because these NalR–CipDS Salmonella Typhi strains have been associated with slower clinical responses to fluoroquinolones and treatment failures, clinical laboratories should attempt to identify these isolates (3,6,7). However, despite the accumulation of clinical, microbiologic, and pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic studies suggesting a resistance breakpoint of >0.125 μg/mL for ciprofloxacin, the clinical breakpoints published by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (susceptibility <1 μg/mL, resistance >4 μg/mL) and those from the antibiogram committee of the French Society for Microbiology (susceptibility <0.5 μg/mL, resistance >1 μg/mL) (www.sfm.asso.fr/nouv/general.php?pa=2) have not been reevaluated (6–9). Use of these standard breakpoints has probably resulted in the underreporting of CipDS Salmonella Typhi strains. The NalR screening test has been proposed as an alternative since the mid–1990s and recommended since 2004 by CLSI and 2010 by the French Society for Microbiology (3,7). This screening test is based on the fact that CipDS Salmonella Typhi isolates with nonsynonymous (NS) mutations in codons 83 or 87 of gyrA are uniformly NalR. However, recent reports have indicated that this approach cannot identify the newly described Salmonella Typhi isolates that are Nal susceptible (NalS)–CipDS for which mechanisms of resistance are not linked to mutations in gyrA (7,10,11). Recently, NS mutations in codons 464 (Ser to Phe) and 466 (Glu to Asp) of gyrB were found in 7 NalS–CipDS Salmonella Typhi isolates (12). We present data on the occurrence and characterization of the resistance mechanisms of NalS–CipDS isolates in 685 Salmonella Typhi isolates of the French National Reference Center for Salmonella (FNRC-Salm).

The Study

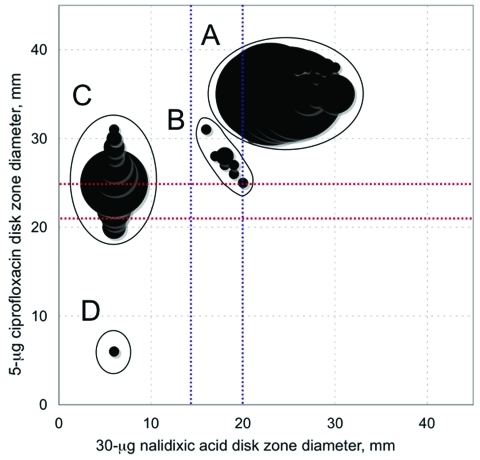

In France, laboratory surveillance of typhoid fever infections is performed by the FNRC-Salm through its network of ≈1,500 hospital and private clinical laboratories. Almost all Salmonella Typhi isolates in France are referred to the FNRC-Salm, and almost all are acquired abroad, mainly in Africa and Asia. Until 2009, CipDS Salmonella Typhi was monitored with the 30-μg Nal screening test. A total of 685 Salmonella Typhi isolates collected during 1997–2009 were reanalyzed to identify NalS–CipDS Salmonella Typhi isolates. The scattergram correlating the zone diameters around the 5-μg ciprofloxacin disk with those of the 30-μg Nal disk showed 4 subpopulations, which were labeled A (554 isolates), B (11 isolates), C (119 isolates), and D (1 isolate) (Figure 1). The characteristics of these populations are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. The QRDRs of gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE genes were studied on 133 isolates selected to represent diversity in terms of year of isolation, geographic origin, and MICs. To analyze the isolate characteristics, we used the following approaches: sequencing (5), denaturing high performance liquid chromatography (4), and Luminex-based genotyping assays (12). QRDR DNA sequences were compared with those of Salmonella Typhi strain Ty2 (GenBank accession no. AE014613). In subpopulation A, 75 isolates had wild-type QRDR sequences, whereas 2 isolates had a gyrB mutation at codon 465 leading to amino acid substitution Gln to Leu. Their Nal MICs were 2 and 4 μg/mL, respectively, and those of Cip were 0.04 μg/mL and 0.08 μg/mL, respectively. Notably, both isolates were acquired in Mexico during 1998 and 2009, respectively. In subpopulation C, the lowest MIC values for Cip (0.06 μg/mL) were associated with a mutation at codon 87 of the gyrA gene, whereas MICs did not increase with the additional mutation in the parE gene. Subpopulation D consisted of 1 isolate, highly resistant to ciprofloxacin, which was acquired by a traveler in India in 2004. This isolate contained 2 NS mutations in the gyrA gene and 1 in the parC gene.

Figure 1.

Scattergrams for 685 Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi isolates correlating the zone diameters around the 5-μg ciprofloxacin disk with those of the 30-μg nalidixic acid disk. Circle sizes are proportional to the number of isolates. Red lines indicate the respective antibiogram committee of the French Society for Microbiology (CA-SFM) breakpoints for ciprofloxacin (susceptible [S] >25; resistant [R] <22 mm). Blue lines indicate the respective CA-SFM breakpoints for nalidixic acid (S >20 and R <15 mm).

Table 1. Characteristics of the 674 Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi isolates belonging to subpopulations A, C, and D, France, 2007–2009*.

| Subpopulation |

No. isolates |

Nal MICs,† μg/mL |

|

Cip MICs,† μg/mL | QRDR mutation (no./no. tested) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC50 |

MIC90 |

Range |

MIC50 |

MIC90 |

Range |

||||

| A | 554 | 4 | 4 | 1–8 | 0.008 | 0.025 | 0.002–0.08 | WT (75/77) | |

| gyrB Leu465 (2/77) | |||||||||

| C | 119 | >256 | >256 | 128–>256 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.06–0.5 | gyrA Phe83 (24/44) | |

| gyrA Tyr83 (12/44) | |||||||||

| gyrA Asn87 (4/44) | |||||||||

| gyrA Gly87 (2/44) | |||||||||

| gyrA Phe83 and parE Asn420 (2/44) | |||||||||

| D | 1 | >256 | 8 | gyrA Phe83, gyrA Asn87, and parC Ile80 | |||||

*Nal, nalidixic acid; Cip, ciprofloxacin; QRDR, quinolone resistance–determining region of the gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE genes; WT, wild type. †MICs of Nal and Cip were determined by Etest strips. MIC50, 50% below; MIC90, 90% below.

.

Table 2. Characteristics of the 11 Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi isolates belonging to subpopulation B, France, 2007–2009.

| Isolate | Year | Geographic origin | Antimicrobial drug resistance type | Disk diffusion, mm |

MIC, μg/mL |

gyrB | Haplotype | PFGE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nal | Cip | Nal | Cip | ||||||||

| 97-5123 | 1997 | Unknown | CipDS | 18 [I] | 28 [S] | 8 [S/S] | 0.125 [S/S] | Tyr464 | Non-H58 | X8 | |

| 02-2759 | 2002 | India | CipDS | 19 [I] | 26 [S] | 4 [S/S] | 0.125 [S/S] | Phe464 | H58 | X2 | |

| 05-1578 | 2005 | India | Pansusceptible | 18 [I] | 28 [S] | 8 [S/S] | 0.047 [S/S] | Asp466 | Non-H58 | X6 | |

| 05-2556 | 2005 | India | CipDS | 17 [I] | 31 [S] | 16 [I/S] | 0.19 [S/S] | Phe464 | Non-H58 | X7 | |

| 05-9141 | 2005 | India | CipDS | 17 [I] | 28 [S] | 12 [I/S] | 0.125 [S/S] | Tyr464 | Non-H58 | X3 | |

| 06-426 | 2006 | India | CipDS | 20 [S] | 25 [S] | 8 [S/S] | 0.125 [S/S] | Tyr464 | Non-H58 | X3 | |

| 07-6086 | 2007 | Tunisia | Pansusceptible | 16 [I] | 31 [S] | 16 [I/S] | 0.047 [S/S] | WT | ND | ND | |

| 08-7675† | 2008 | India | ASCSulTmpSXTCipDS | 18 [I] | 28 [S] | 8 [S/S] | 0.125 [S/S] | Phe464 | H58 | X1 | |

| 09-1986† | 2008 | India | ASCSulTmpSXTCipDS | 18 [I] | 27 [S] | 8 [S/S] | 0.125 [S/S] | Phe464 | ND | X1 | |

| 09-0350 | 2009 | Unknown | CipDS | 19 [I] | 27 [S] | 8 [S/S] | 0.125 [S/S] | Phe464 | Non-H58 | X5 | |

| 09-2317 | 2009 | French Guyana | Pansusceptible | 19 [I] | 32 [S] | 8 [S/S] | 0.032 [S/S] | Glu468 | Non-H58 | X4 | |

*PFGE, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis; Nal, nalidixic acid; Cip, ciprofloxacin; WT, wild type; ND, not determined; A, ampicillin; S, streptomycin, C, chloramphenicol; Su, sulfamethoxazole; Tmp, trimethoprim; SXT, cotrimoxazole; CipDS, decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin. Disk diffusion test was performed and interpreted ([S], susceptible; [I], intermediate) following recommendations of antibiogram committee of the French Society for Microbiology. MICs were determined by Etest strips, and categorization was made according to the French Society for Microbiology and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. †Previously described same patient (13).

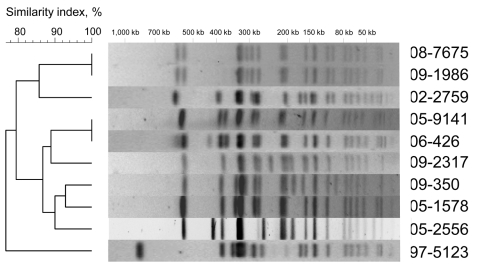

Eleven isolates of subpopulation B were categorized as susceptible to Nal by determining MICs and by using CLSI breakpoints (susceptibility, <16 μg/mL; resistance, >32 μg/mL). Of the 11 isolates, 8 (from 7 patients) had a ciprofloxacin MIC >0.125 μg/mL and were thus classified as CipDS isolates. We were able to review the medical records of 2 patients infected with a NalS–CipDS isolate. One patient (isolates 08-7675 and 09-1986) relapsed 15 days after completion of the treatment (oral ofloxacin, 200 mg 2×/d for 8 days) (13). The second patient (isolate 05-2556) was treated with extended-spectrum cephalosporins, and no fluoroquinolones. Regarding the resistance mechanisms the plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance–conferring genes qnr (qnrA, B, S, D), qepA, and aac(6′)-Ib-cr were not detected by PCR (5,14). The QRDRs of gyrA, parC, and parE genes were of a wild type, whereas an NS mutation was found in gyrB for all but 1 isolate. However, only the 8 isolates with mutations at codon 464 were NalS–CipDS. To assess whether these isolates were genetically related, haplotyping (4) and XbaI-pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) subtyping (5) were performed. On the strength of the results, we concluded that the gyrB mutation was acquired independently by strains belonging to different PFGE types (Figure 2). According to a newly developed single nucleotide polymorphism assay (Y.S.), 2 of these strains belong to the current emerging H58 Asian population (4), whereas the others do not (Table 2). In our study, the NalS–CipDS isolates with gyrB mutations at codon 464 were most often non–multidrug-resistant and acquired mainly in India. Our first NalS–CipDS isolate was isolated 13 years ago, and since is rare (prevalence ≈1%.). Although Cooke et al. (10) did not characterize isolates for their resistance mechanisms, they reported that NalS–CipDS represented 11.6% (49/421) of Salmonella Typhi isolated in England, Scotland, and Wales during 1999–2003, while Lynch et al. (11) reported that such isolates were 4.6% (36/770) of Salmonella Typhi isolates identified in the United States during 1999–2006. Epidemiologic data were available for 39 isolates in the British study, 18 of which were acquired in India, 8 in Pakistan, and 4 in Bangladesh (10). The 10-fold difference in the prevalence observed between our study and that of Cooke et al. are probably related to the historical links and the subsequent population flow between the United Kingdom and the Indian subcontinent.

Figure 2.

XbaI pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) profiles obtained from 10 Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi isolates belonging to subpopulation B. The dendrograms generated by BioNumerics version 3.5 software (Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium) show the results of cluster analysis on the basis of PFGE fingerprinting. Similarity analysis was performed by using the Dice coefficient, and clustering was done by using the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic averages.

Conclusions

NalS–CipDS Salmonella Typhi isolates originating from Asia comprise ≈1% of Salmonella Typhi isolates in France but are more prevalent in the United States and the United Kingdom. The NS gyrB mutation at codon 464 was found exclusively in NalS–CipDS isolates; however, the effects of this mutation need to be formally demonstrated by site-directed mutagenesis. Furthermore, the involvement of an efflux system, such as AcrAB-TolC and OqxA, or the qnrC gene, have not been investigated and cannot be excluded.

Whatever the molecular mechanism of resistance of such strains, the main concern is detection of such isolates in clinical practice to prevent fluoroquinolone treatment failures. Consequently, the NalR screening test should no longer be recommended and ciprofloxacin drug MICs should be determined for all Salmonella Typhi isolates instead. There is also a clear need to reevaluate the clinical breakpoints for this pathogen.

Acknowledgment

We thank all the corresponding laboratories of the French National Reference Center for Salmonella network for their assistance.

This work was funded by the Institut Pasteur (M.A.-D., F.-X.W.), the Institut de Veille Sanitaire (M.A.-D., F.-X.W.), and the Science Foundation of Ireland (grant no. 05/FE1/B882 to Y.S. and M.A.).

Biography

Mrs Accou-Demartin is a public health technologist at the FNRC-Salm. Her primary research interest focuses on surveillance, molecular epidemiology, and antimicrobial drug–resistance mechanisms of Salmonella spp.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Accou-Demartin M, Gaborieau V, Song Y, Roumagnac P, Marchou B, Achtman M, et al. Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi with nonclassical quinolone resistance phenotype [expedited]. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2011 Jun [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1706.101242

References

- 1.Crump JA, Mintz ED. Global trends in typhoid and paratyphoid fever. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:241–6. 10.1086/649541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wain J, Kidgell C. The emergence of multidrug resistance to antimicrobial agents for the treatment of typhoid fever. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2004;98:423–30. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2003.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wain J, Hoa NT, Chinh NR, Vinh H, Everett MJ, Diep TS, et al. Quinolone-resistant Salmonella typhi in Vietnam: molecular basis of resistance and clinical response to treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1404–10. 10.1086/516128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roumagnac P, Weill FX, Dolecek C, Baker S, Brisse S, Chinh NT, et al. Evolutionary history of Salmonella Typhi. Science. 2006;314:1301–4. 10.1126/science.1134933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le TA, Fabre L, Roumagnac P, Grimont PA, Scavizzi MR, Weill FX. Clonal expansion and microevolution of quinolone-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi in Vietnam from 1996 to 2004. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3485–92. 10.1128/JCM.00948-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aarestrup FM, Wiuff C, Mølbak K, Threlfall EJ. Is it time to change fluoroquinolone breakpoints for Salmonella spp.? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:827–9. 10.1128/AAC.47.2.827-829.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crump JA, Kretsinger K, Gay K, Hoekstra RM, Vugia DJ, Hurd S, et al. Clinical response and outcome of infection with Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi with decreased susceptibility to fluoroquinolones: a United States FoodNet Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1278–84. 10.1128/AAC.01509-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crump JA, Barrett TJ, Nelson JT, Angulo FJ. Reevaluating fluoroquinolone breakpoints for Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi and for non-Typhi salmonellae. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:75–81. 10.1086/375602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Booker BM, Smith PF, Forrest A, Bullock J, Kelchlin P, Bhavnani SM, et al. Application of an in vitro infection model and simulation for reevaluation of fluoroquinolone breakpoints for Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:1775–81. 10.1128/AAC.49.5.1775-1781.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooke FJ, Day M, Wain J, Ward LR, Threlfall EJ. Cases of typhoid fever imported to England, Scotland and Wales (2000–2003). Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:398–404. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lynch MF, Blanton EM, Bulens S, Polyak C, Vojdani J, Stevenson J, et al. Typhoid fever in the United States, 1999–2006. JAMA. 2009;302:859–65. 10.1001/jama.2009.1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song Y, Roumagnac P, Weill FX, Wain J, Dolecek C, Mazzoni CJ, et al. A multiplex single nucleotide polymorphism typing assay for detecting mutations that result in decreased fluoroquinolone susceptibility in Salmonella enterica serovars Typhi and Paratyphi A. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010. Jun 1. PMID: 20511368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Gaborieau V, Weill FX, Marchou B. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi with decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin: a case report [in French]. Med Mal Infect. 2010;40:691–5. 10.1016/j.medmal.2010.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sjölund-Karlsson M, Howie R, Rickert R, Krueger A, Tran TT, Zhao S, et al. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance among non-Typhi Salmonella enterica isolates, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1789–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]