Abstract

In structural biology, pulsed field gradient (PFG) NMR for characterization of size and hydrodynamic parameters of macromolecular solutes has the advantage over other techniques that the measurements can be recorded with identical solution conditions as used for NMR structure determination or for crystallization trials. This paper describes two transverse relaxation-optimized (TRO) 15N-filtered PFG stimulated-echo (STE) experiments for studies of macromolecular translational diffusion in solution, 1H-TRO-STE and 15N-TRO-STE, which include CRINEPT and TROSY elements. Measurements with mixed micelles of the Escherichia coli outer membrane protein X (OmpX) and the detergent Fos-10 were used for a systematic comparison of 1H-TRO-STE and 15N-TRO-STE with conventional 15N-filtered STE experimental schemes. The results provide an extended platform for evaluating the NMR experiments available for diffusion measurements in structural biology projects with molecular particles of different size ranges. An initial application of the 15N-TRO-STE experiment with very long diffusion delays showed that the tedradecamer structure of the 800 kDa Thermus thermophilus chaperonin GroEL is preserved in aqueous solution over the temperature range 25–60°C.

This communication evaluates and applies transverse relaxation optimization (TRO) in NMR experiments that are used to measure translational diffusion of macromolecular solutes in liquids. Renewed interest in hydrodynamic measurements is generated by increased focus of structural biology on supramolecular structures, which requires analytical tools for the characterization of entities consisting of two or multiple non-covalently linked molecules. Among the methods used, which include also ultracentrifugation, quasi-elastic light scattering, small angle X-ray scattering and small angle neutron scattering, pulsed field gradient (PFG) NMR has the advantage that the measurements can be carried out under conditions of protein and detergent concentrations, ionic strength and temperature that are closely similar to those used for NMR structure determination and crystallization trials. In line with the aforementioned interest in hydrodynamic studies of supramolecular structures, prominent applications of PFG-NMR diffusion measurements include monitoring of protein association,1–4 characterization of protein–ligand interactions,5–7 and determination of the size and shape of detergent micelles and membrane protein–detergent mixed micelles.8–11

NMR diffusion measurements initially used the spin echo (SE) experiment.12 Subsequently the stimulated echo (STE) experiment, which enables storing the magnetization along the z-axis during waiting periods when it is not being dephased or re-phased by magnetic field gradients,13 has been widely used for studies of macromolecular systems with slow longitudinal relaxation and fast transverse relaxation, i.e., with T1 ≫ T2, where T1 and T2 are the longitudinal and transverse nuclear spin relaxation times, respectively. More recently, heteronuclear filters were incorporated into STE pulse sequences, in order to distinguish between signals arising from stable-isotope-labeled and unlabeled components in the solutions studied,14 and the X-STE experiment15,16 was designed to extend the size limit for measurements of diffusion coefficients of isotope-labeled molecules beyond the STE limit of about 50 kDa. This was achieved by storing the magnetization during the diffusion delay on either 15N- or 13C-spins, which both have slower relaxation rates than 1H-spins in the same protein. Although the diffusion interval in X-STE could thus be increased about 10-fold when compared to STE,15 transverse relaxation during the INEPT 15N,1H-magnetization transfer steps became a limiting factor when working with large molecular sizes. To further extend the size range, we now replaced the INEPT coherence transfers in 15N-filtered PFG-STE experiments by CRINEPT.17 Studies of mixed micelles of the outer membrane protein X (OmpX) from Escherichia coli and the detergent Fos-10 with the experiments 1H-TRO-STE and 15N-TRO-STE were used to compare the performance of corresponding experiments with and without TRO. The 15N-TRO-STE experiment was then applied for studies of the hydrodynamic properties of the 800 kDa tetradecameric chaperonin protein GroEL from Thermus thermophilus18,19 under variable solution conditions.

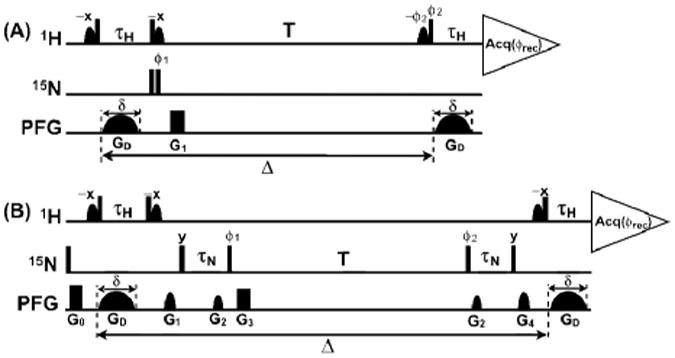

The 1H-TRO-STE experimental scheme (Fig. 1A) is based on a heteronuclear-filtered PFG-STE experiment (Fig. 1C in Tillet et al.6) in which the magnetization is stored in the bilinear HzNz state during the delay T. In 1H-TRO-STE the delay τH is adjusted for optimal CRINEPT transfer17 rather than being set to |2JHN |–1 = 5.4 ms6 . To avoid radiation damping during the diffusion delay and prevent saturation of the labile protein protons, water-selective soft pulses are applied to keep the bulk water magnetization along the z-axis during the entire course of the experiment, and no 15N-decoupling is applied during acquisition in order to benefit from the 15N–1H TROSY effect19. The 15N-TRO-STE scheme (Fig. 1B) has in common with the X-STE experiment of Ferrage et al.15 that losses due to longitudinal relaxation are reduced by keeping the magnetization in the Nz state during the delay T. To further achieve efficient TRO, we introduced a 1H-to-15N magnetization transfer element consisting of two consecutive CRINEPT steps, τH and τN, and added 15N–1H TROSY by eliminating 15N-decoupling during acquisition. In the practice of PFG-STE experiments one measures the ratio of a signal, S, which is recorded with variable amplitudes of the gradient pulse GD and therefore attenuated by diffusion, and a reference signal, S0, which is recorded with very weak GD amplitudes:

Figure 1.

TRO-STE (transverse relaxation-optimized 15N-filtered PFG-stimulated echo) pulse schemes for measuring translational self-diffusion constants, Dt, of macromolecules in solution. Vertical bars on the lines marked 1H and 15N indicate non-selective 90°-pulses, and sine-bell shapes on the line 1H indicate water-selective 90°-pulses. The line marked PFG indicates the durations and shapes of pulsed magnetic field gradients applied along the z-axis. The gradients GD, which encode the variable diffusion delay, Δ, have adjustable amplitudes and a fixed duration, δ, of 4.5 ms. The “crusher gradients” G0 to G4 are used to dephase unwanted magnetization. The CRINEPT transfer delay τH can be optimized using CRINEPT buildup measurements, and τn can be adjusted for high sensitivity using a 15N-TRO-STE experiment with constant GD gradient amplitude. For both delays, typical lengths thus found are between 3.0 and 5.4 ms. (A) 1H-TRO-STE. For the applications in this paper, the duration and strength of the rectangular gradient G1 were 500 μs and 31 G/cm. Phase cycling: ϕ1= x,–x,x, –x; ϕ2= x, x,y,y; ϕrec= x,–x,–x,x. (B) 15N-TRO-STE. Duration, strength and shape of the gradients G0 to G4: G0, 1 ms, 27 G/cm, rectangular; G1, 0.5 ms, 23 G/cm, sine-bell; G2, 0.3 ms, 13 G/cm, sine-bell; G3, 0.5 ms, 31 G/cm, rectangular; G4, 0.5 ms, 21 G/cm, sine-bell. Phase cycling: ϕ1 = y,–y,y,–y; ϕ2 = y,y,–y,–y; ϕrec = x,–x,–x,x.

| (1) |

In Eq. (1), q = γHsGDδ is the area of the gradient pulse GD, where γH is the proton gyromagnetic ratio and s represents the shape of the diffusion gradient with peak amplitude GD and duration δ, Dt is the translational diffusion constant, and δ is the diffusion delay (Fig. 1). Both signals, S0 and S, are dampened by longitudinal 1H and 15N relaxation during the delay T, affected by transverse 1H and 15N relaxation during the transfer periods, τH and τN, and modulated by scalar couplings. The resulting signal attenuation can be described by the factors fH-TRO-STE and fN-TRO-STE:

| (2) |

| (3) |

Γ̄ H and Γ̄N are average transverse auto-relaxation rate constants of in-phase and anti-phase 15N and 1H coherences:20,21

| (4) |

| (5) |

ΓNz,Nz and ΓHzNz,Hz,Nz are the longitudinal relaxation rate constants for the Nz and the HzNz states. For 15N-TRO-STE the signal attenuation caused by diffusion between the two gradients G2 (length: 0.3 ms, gradient strength: 13 G/cm) was estimated to be < 1 ‰ even for long diffusion delays (Δ = 1 s) and fast diffusion (Dt = 2 × 10–10 m2/s), and it was therefore not considered in Eq (3).

The coefficients ΛH, ΛN and KN are given by Eqs. (6)–(8), where and are the transverse 1H and 15N cross-correlated relaxation rate constants:

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

The equations (6)–(8) describe linear combinations of polarization transfers via scalar coupling (sine function) and via CRIPT (hyperbolic sine and cosine functions). For short rotational correlation times τc, the cross-correlated relaxation rate constants and are negligibly small and only the INEPT pathway given by the second term in Eqs. (6)–(8) contributes significantly to the CRINEPT transfer, whereas for τc-values > 100 ns, and become large and CRIPT is the dominant polarization transfer mechanism in the CRINEPT element.17 In the absence of spin relaxation, the signal intensity in the 15N-TRO-STE experiment would be reduced by a factor of 2 when compared to other STE-type experiments (see Eqs. (2) and (3)). Nonetheless, model calculations of the relative sensitivities of the 15N-TRO-STE, 1H-TRO-STE and X-STE experiments for translational diffusion measurements predict that 15N-TRO-STE is a promising approach for studies of large supramolecular structures with rapid transverse spin relaxation [Figure S1 in the Supporting Information (SI)].

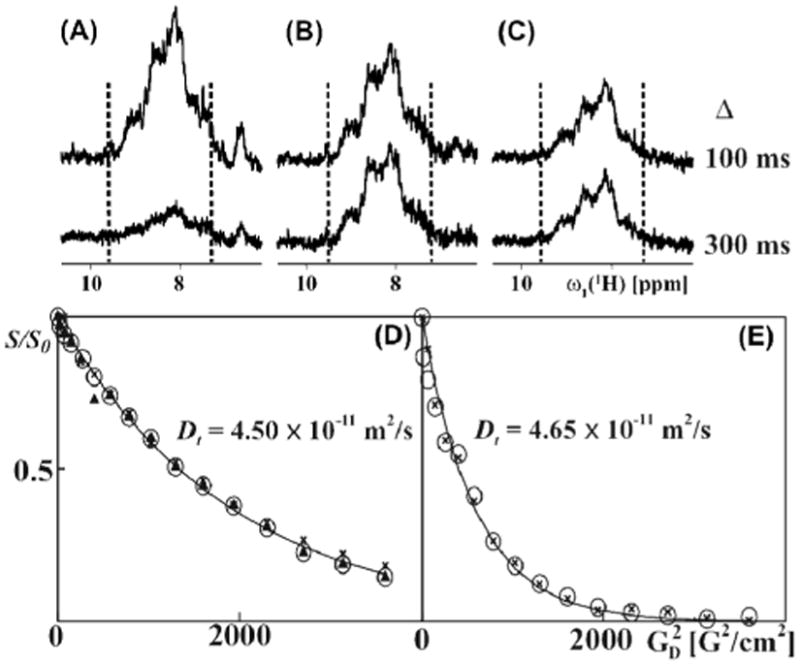

For an experimental validation of the predictions in Fig. S1, we recorded 15N-TRO-STE, 1H-TRO-STE and X-STE experiments of [u-15 N,u∼80%-2H]-OmpX (outer membrane protein X from E. coli) reconstituted in mixed micelles with the detergent Fos-10, with Δ values (Fig. 1) ranging from 100 ms to 300 ms. At a sample temperature of 4º C, the effective rotational correlation time, τc, of OmpX/Fos-10 micelles was = 52 ns, as determined using the TRACT experiment. For this system, 15N-TRO-STE is approximately 1.5-fold more sensitive than X-STE (Fig. 2, B and C), which reflects the higher efficiency of the CRINEPT transfers17 used in 15N-TRO-STE when compared to the INEPT transfers in the X-STE experiment. This gain is close to the 1.3-fold increase in sensitivity of 15N-TRO-STE over the X-STE experiment predicted for uniformly 80% 2H-labeled antiparallel β-sheets in particles with the size of OmpX/Fox-10 micelles (Fig. S1A in the SI). For a diffusion delay of 100 ms the 1H-TRO-STE experiment was about two-fold more sensitive than 15N-TRO-STE, but its signal intensity fell off rapidly for longer delays Δ (Fig. 2A). The small loss of 15N-TRO-STE signal intensity between Δ-values of 100 ms and 300 ms (Fig. 2B) probably arises primarily because the KN magnetization transfer pathway (Eq. (3)) becomes less efficient for long diffusion delays due to longitudinal proton relaxation of the HzNz state.

Figure 2.

Experimental comparison of the 1H-TRO-STE, 15N-TRO-STE and X-STE pulse schemes for translational diffusion measurements, based on data collected with [u- 15N,u∼80%- 2H]-OmpX in mixed micelles with the unlabeled detergent Fos-10 at 4°C (A)–(C): 1D 15N-filtered 1H NMR spectra measured using 1H-TRO-STE, 15N-TRO-STE and X-STE, respectively, with gradient strengths, GD, of 3 G/cm, and diffusion delays Δ (see Fig. 1) of 100 and 300 ms. The signal intensity between the broken vertical lines was evaluated in order to obtain the values for S0 and S which were used in Eq. (1) to determine the diffusion constants indicated in panels (D) and (E). (D) NMR data used to determine the diffusion constant acquired with Δ = 100 ms. (E) Same as (D), measured with Δ = 300 ms. In (D) and (E), relative signal intensities are plotted versus the square of the gradient strength. In (D), filled triangles, crosses and open circles represent the data obtained with the 1H-TRO-STE, X-STE and 15N-TRO-STE experiments, respectively. In (E), only the X-STE and 15N-TRO-STE data are shown. Translational diffusion constants, Dt, are indicated as calculated rom the 15N-TRO-SE data using a single-exponential fit. For the TRO-STE experiments, the encoding gradients, δ (Fig. 1), had a length of 4.5 ms. For the X-STE experiment, bipolar gradients of length 2.25 ms were used.15 Each of the one-dimensional spectra is the result of accumulating 128 transients in 5 minutes.

For measurements of diffusion constants, the amplitude of the gradients GD (Fig. 1) was incremented linearly in 16 steps. The resulting decay of the signal intensity as a function of the square of the GD amplitude is single-exponential, as predicted by Eq. (1), yielding values for the diffusion coefficient of OmpX/Fos-10 micelles between 4.50 and 4.65 × 10−11 m2/s (Fig. 2, D and E). Overall, the model calculations of Fig. S1 and the experiments with OmpX/Fos-10 mixed micelles (Fig. 2) yielded three key results. Firstly, the 1H-TRO-STE scheme provides high sensitivity for work with small molecular particles which can be studied with Δ-values (Fig. 1A) up to about 100 ms. 1H-TRO-STE may therefore become an attractive alternative to other experiments12–16 available for studies of molecular sizes corresponding to τc-values up to about 40 ns. Secondly, for measurements with diffusion delays Δ longer than 100 ms, as needed for studies of large molecular sizes, the 15N-TRO-STE scheme yields the best sensitivity. Thirdly, identical translational diffusion coefficients for OmpX/Fos-10 mixed micelles were obtained with either of the three experimental schemes used in Fig. 2, A–C, with Δ = 100 ms, and a closely similar value was obtained with Δ = 300 ms (because of the low sensitivity (Fig. 2A), the 1H-TRO-STE data obtained with Δ = 300 ms are not included in Fig. 2E). For each size range one may thus select the experimental scheme that yields the best sensitivity, without running risks that the diffusion measurements might be biased by the selection of the particular experiment.

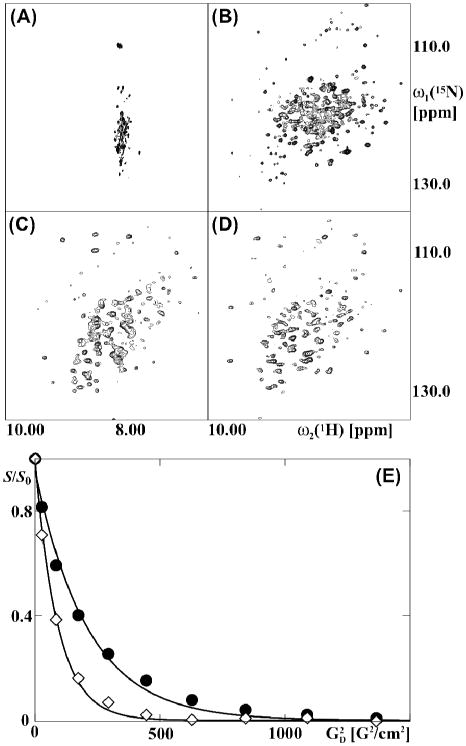

For an initial assessment of the uniformly [2H,15N]-labeled chaperonin Tth GroEL we measured 15N-1H NMR correlation spectra. Key observations resulted from the temperature dependence of the 2D [15N,1H]-TROSY spectrum on the one hand, and the 2D [15N,1H]-CRIPT-TROSY spectrum on the other hand (Fig. 3). Small dispersion of the resonances along the ω2(1H)-axis in the 2D [15N,1H]-TROSY spectrum at 25 °C (Fig. 3A) indicates that the observed signals are from flexibly disordered polypeptide segments devoid of regular secondary structure.23 This is in line with previous studies,24,25 which had shown that transverse relaxation is too fast to allow observation of NMR signals from structured polypeptide segments within particles of several hundred kDa in 2D [15N,1H]-TROSY spectra recorded at room temperature. The spectrum of Fig. 3A is strikingly different from the widely dispersed 2D [15N,1H]-correlation map with more than 300 resolved cross-peaks (Fig. 3B) that was obtained from the 2D [15N, 1H]-TROSY measurement at 60 °C and is typical for a folded globular protein. In contrast, the 2D [15N,1H]-CRIPT-TROSY spectra recorded at 25 °C and at 60 °C have similar overall features (Fig. 3, C and D), and they also show comparable dispersion of the 1H chemical shifts to that in the [15N, 1H]-TROSY spectrum at 60 °C (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

NMR spectra and diffusion measurements of the uniformly [15N, 2H]-labeled 800 kDa protein GroEL from Thermus thermophilus. (A) and (B): 2D [15N,1H]-TROSY spectra acquired at 25 °C and at 60 °C . (C) and (D): 2D [15N, 1H]-CRIPT-TROSY spectra acquired at 25 °C and 60 °C with CRIPT transfer delays of 1.0 ms and 2.0 ms, respectively. (E) NMR data used to determine the diffusion constant with 15N-TRO-STE experiments at 25 °C (filled circles) and 60 °C (open diamonds). The spectra were recorded with δ = 4.5 ms and Δ = 800 ms (see Fig. 1). S and S0 were evaluated as the sum of the signal intensities in the 1H chemical shift range 8.7 to 9.6 ppm. T he resulting values for the diffusion coefficients, Dt, were determined by fitting the data to Eq. 1 (see Table S1). The parameter settings used to collect and process the data are described in the Methods section in the SI.

For a more detailed interpretation of the data in Fig. 3, in particular in view of the extensive differences, between the [15N,1H]-TROSY spectra at 25 °C and at 60 °C (Fig. 3, A and B), it was of interest to characterize the oligomeric state of Tth GroEL at the different temperatures used. We therefore measured 15N-TRO-STE experiments to determine the translational diffusion coefficient of Tth GroEL, Dt,EL, at 25 °C and at 60 °C (Fig. 3E). We further determined the diffusion coefficient of the internal standard DSS, Dt,DSS, at the same temperatures, and calculated the relative diffusivity of Tth GroEL, dEL, using Eq. S1. It has been shown previously that convection in the sample can lead to an overestimation of the diffusion coefficient Dt in PFG-STE experiments26 . Jerschow and Müller have developed elegant NMR experiments to eliminate these convection artifacts27, however, these methods are difficult to implement into X-STE type experiments. We therefore chose the alternative to work with samples with restricted volumes . In order to assess the influence of convection on the measured Dt values at 60 °C, we measured PFG-STE experiments of HDO at variable temperatures and diffusion delays (Fig. S2), which revealed that by using the experimental set-up described in the methods section of the SI, Dt measurements at 60 °C were not measurably affected by convection.

The value of 3.8 × 10−1 m2/s for Dt,EL at 25 °C (Table S1) is much smaller than the Dt value expected for a 58 kDa Tth GroEL monomer, and it is characteristic for a large particle in the molecular size-range of tetradecameric Tth GroEL.28 The diffusion constant of the reference compound DSS, Dt,DSS, is 2.4 times larger at 60 °C than at 25 °C (Table S1), which is in satisfactory agreement with the increase by a factor 2.1 that is predicted based on the temperature dependence of the viscosity, η, for H2O.29 Finally, the relative diffusivity for Tth GroEL, which is independent of the solvent viscosity and the temperature, has closely similar values at 25 °C and 60 °C (Table S1). The combined data on GroEL and DSS then show that the value of 10.1 × 10–1 m2/s for Dt,EL at 60 ºC can be rationalized by the decrease of the solvent water viscosity η with increasing temperature, and that the tetradecameric state of Tth GroEL is highly populated also at 60 °C. The improved quality of the 2D [15N, 1H]-TROSY spectrum of Tth GroEL at 60 °C, when compared to the corresponding spectrum at 25 °C (Fig. 4, A and B), is therefore due to the shorter effective τc-value resulting from the reduced solvent viscosity at 60 ºC and not to dissociation of the tetradecameric functional state of the chaperonin.

In conclusion, the presently introduced 1H-TRO-STE and 15N-TRO-STE experiments enable improved measurements of the translational diffusion coefficients for 15N-labeled polypeptides in large complexes. In particular, the fully transverse relaxation-optimized experiment 15N-TRO-STE opens the possibility to determine small diffusion coefficients of polypeptide chains in su-pramolecular structures of several hundred kDa in size.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. George W. Farr and Navneet K. Tyagi for help with the preparation of Tth GroEL. This work was supported by the Joint Center for Innovative Membrane Protein Technologies (JCIMPT; NIH Roadmap Initiative grant P50GM073197 for technology development). K.W. is the Cecil H. and Ida M. Green Professor of Structural Biology at The Scripps Research Institute.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. The Bruker AVANCE pulse programs for the H-TRO-STE and the N-TRO-STE experiments are shown in the listings S1 and S2, respectively. A summary of sample preparation and NMR spectroscopy are available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Altieri AS, Hinton DP, Byrd RA. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:7566–7567. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dingley A, Mackay J, Chapman B, Morris M, Kuchel P, Hambly B, King G. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:321–328. doi: 10.1007/BF00197813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ilyina E, Roongta V, Pan H, Woodward C, Mayo K. Biochemistry. 1997;36:3383–3388. doi: 10.1021/bi9622229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krishnan V. J Magn Reson. 1997;124:468–473. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1996.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hajduk PJ, Olejniczak ET, Fesik SW. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:12257–12261. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tillett M, Horsfield M, Lian LY, Norwood T. J Biomol NMR. 1999;13:223–232. doi: 10.1023/a:1008301324954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodge P, Monvisade P, Morris GA, Preece I. Chem Commun. 2001;2001:239–240. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vinogradova O, Sonnichsen F, Sanders C. J Biomol NMR. 1998;11:381–386. doi: 10.1023/a:1008289624496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chou JJ, Baber JL, Bax A. J Biomol NMR. 2004;29:299–308. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000032560.43738.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krueger-Koplin R, Sorgen P, Krueger-Koplin S, Rivera-Torres IO, Cahill S, Hicks D, Grinius L, Krulwich T, Girvin M. J Biomol NMR. 2004;28:43–57. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000012875.80898.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stanczak P, Horst R, Serrano P, Wüthrich K. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:18450–18456. doi: 10.1021/ja907842u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stejskal EO, Tanner JE. J Chem Phys. 1965;42:288–292. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanner JE. J Chem Phys. 1970;52:2523–2526. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dingley A, Mackay J, Shaw G, Hambly B, King G. J Biomol NMR. 1997;10:1–8. doi: 10.1023/A:1018339526108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrage F, Zoonens M, Warschawski D, Popot JL, Bodenhausen G. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:2541–2545. doi: 10.1021/ja0211407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarkar R, Moskau D, Ferrage F, Vasos P, Boden-hausen G. J Magn Reson. 2008;193:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2008.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riek R, Wider G, Pervushin K, Wüthrich K. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4918–4923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimamura T, Koike-Takeshita A, Yokoyama K, Ma-sui R, Murai N, Yoshida M, Taguch H, Iwata S. Structure. 2004;12:1471–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pervushin K, Riek R, Wider G, Wüthrich K. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:12366–12371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brutscher B. Conc Magn Reson. 2000;12A:207–229. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luginbühl P, Wüthrich K. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spect. 2002;40:199–247. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee D, Hilty C, Wider G, Wüthrich K. J Magn Reson. 2006;178:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wüthrich K. NMR of Proteins and Nucleic Acids. Wiley; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fiaux J, Bertelsen EB, Horwich AL, Wüthrich K. Nature. 2002;418:207–211. doi: 10.1038/nature00860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riek R, Fiaux J, Bertelsen EB, Horwich AL, Wüthrich K. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:12144–12153. doi: 10.1021/ja026763z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hedin N, Yu TY, Furo I. Langmuir. 2000;16:7548–7550. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jerschow A, Müller N. J Magn Reson. 1997;125:372–375. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Squire PG, Himmel ME. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1979;196:165–177. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(79)90563-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atkins PW. Physical Chemistry. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1995. p. C27. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.