Summary

We performed a prospective, open-label, randomised controlled trial comparing the air-Q® against the LMA-ProSeal™ in adults undergoing general anaesthesia. One hundred subjects (American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status 1–3) presenting for elective, outpatient surgery were randomly assigned to 52 air-Q® and 48 ProSeal devices. The primary study endpoint was airway seal pressure. Oropharyngolaryngeal morbidity was assessed secondarily. Mean (SD) airway seal pressures for the air-Q® and ProSeal were 30 (7) cmH2O and 30 (6) cmH2O, respectively (p = 0.47). Postoperative sore throat was more common with the air-Q® (46% vs 38%, p = 0.03) as was pain on swallowing (30% vs 5%, p = 0.01). In conclusion, the air-Q® performs well as a primary airway during the maintenance of general anaesthesia with an airway seal pressure similar to that of the ProSeal, but with a higher incidence of postoperative oropharyngolaryngeal complaints.

The air-Q® Intubating Laryngeal Airway (air-Q; Mercury Medical, Clearwater, FL, USA) is a new supraglottic airway device (SAD) intended for use as a primary airway as well as an aid for tracheal intubation in situations of anticipated or unanticipated difficult airways. Its design includes a large airway tube inner diameter (ID), a short airway tube length and a tethered, removable standard 15-mm circuit adapter. These features enable direct insertion of larger tracheal tubes (up to 7.5 and 8.5 mm IDs for air-Q sizes 3.5 and 4.5, respectively) through the airway tube and reduce the tracheal tube length requirements imposed by some SADs to ensure tracheal tube cuff placement below the level of the vocal cords [1].

Amongst current SADs, the LMA-ProSeal™ (LMA North America, San Diego, CA, USA) has demonstrated its superior ability to seal the airway even under high pressure (~27–36 cmH2O) [2], which allows it to be used reliably with or without positive pressure ventilation. This seal is significantly higher than that reported for the LMA-Classic™ (cLMA; LMA North America, San Diego, CA, USA), of ~16–22 cmH2O [2]. Nonetheless, the cLMA has been reported to be an excellent conduit for fibreoptic-aided intubation [3, 4], particularly by less experienced practitioners [5]. Because of the configuration of the airway tube relative to the bowl of the mask of the ProSeal (slightly off to the right) and its smaller airway tube ID compared with the cLMA, intubating directly or using a fibreoptic exchange technique through the device may be more challenging and negate its potential advantage with respect to lung ventilation [6].

Data on use of the air-Q is currently limited. Paediatric case reports [7, 8], a prospective, observational study in adults [9] and two prospective randomised trials comparing blind intubation rates through the air-Q and other SADs comprise the literature [10, 11]. Two of the studies used an earlier generation of the PVC-based, single-use device [9, 10] and only one reported airway seal pressure achieved with the device [9]. Thus, our primary goal was to compare the airway seal pressures (as a surrogate for efficacy of lung ventilation) of the newest generation, silicone-based, reusable air-Q and the ProSeal in adults undergoing general anaesthesia. We hypothesised that the seal of the air-Q would be commensurate with other frequently used SADs, but not as good as the ProSeal, as our early experience, albeit using the single-use device, suggested an airway seal pressure on the order of 25 cmH2O [12]. Secondly, we sought to compare: overall insertion success; ease of insertion; positioning of the device in relation to the vocal cords; haemodynamic effects after initial placement; subjective ratings of overall clinical usefulness; and peri-operative oropharyngolaryngeal morbidity, between the devices.

Methods

The University of Wisconsin Health Sciences Institutional Review Board approved this prospective, open-label, randomised controlled trial. After written informed consent, patients were randomly assigned by toss of a coin to receive either an air-Q or ProSeal. All patients ≥ 18 years of age, scheduled for elective outpatient surgery in which general anaesthesia with the placement of a SAD was planned, were eligible. Patients with symptomatic or untreated gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, prior oesophagectomy, hiatus hernia, vomiting within 24 h of surgery, known oropharyngeal pathology making a proper SAD fit unlikely, or any condition for which the primary anaesthesia team deemed intubation with a tracheal tube to be necessary, were excluded. The study population did not result from screening all patients presenting for outpatient surgery, but rather represents a sample taken from consecutive screening on days when one of three investigators (REG, KMS and AMJ) was scheduled to be in the outpatient surgery centre.

After intravenous access was established, patients were premedicated with 1–2 mg midazolam at the discretion of the attending anaesthesiologist and transported to the operating room. Standard monitors, including pulse oximetry, electrocardiography, capnography, non-invasive arterial blood pressure and inspired / expired multi-gas analysis, were placed. Denitrogenation was accomplished by tidal breathing of 10 l.min−1 oxygen 100% for > 3 min. General anaesthesia was induced intravenously with fentanyl (0–2 µg.kg−1) and propofol (2–3 mg.kg−1) and maintained with 2–3% sevoflurane in 50% oxygen delivered via a circle anaesthesia system. Neuromuscular blocking drugs were not used as part of the induction, but only afterwards to facilitate surgical conditions at the discretion of the primary anaesthesia providers.

When the patient became unresponsive to a jaw thrust, the assigned device was placed. Before placement, the devices were tested for leaks and lubricated on the tip and posterior surface with water-soluble surgical gel. The use of viscous lidocaine and / or other topical anaesthetics was not allowed. For patients assigned to the air-Q group, size 3.5 and 4.5 devices were placed in women and men, respectively. Before insertion, just enough air was withdrawn from the device to cause visible dimpling in the posterior portion of the cuff. The device was then placed in the patient’s mouth behind the tongue and the index finger of the operator’s left hand was used to guide the tip of the cuff around the base of the tongue. Simultaneously, a caudad force was applied with the operator’s right hand on the airway tube and the device was rotated inwardly and forward into position. If initial resistance to advancement was met, a jaw lift with the operator’s left hand was performed, while the device was rotated inwardly and forward into position with the right hand. When advancement met a firm stop, the cuff was inflated with 15–20 ml air (15 ml for size 3.5 and 20 ml for size 4.5) in accordance with the manufacturer’s labelled recommendation and assessed for adequate ventilation, defined as measurement of end-tidal carbon dioxide on the anaesthesia monitor and observation of a rising chest with manual inflation using the breathing bag of the anaesthesia circle system. Pressure manometer-guided cuff inflation was not used for the air-Q as the manufacturer makes no recommendation for cuff inflation pressure, but only a maximum cuff inflation volume.

For patients assigned to the ProSeal group, size 4 and 5 devices were placed in women and men, respectively, using the unassisted, gum elastic bougie-guided insertion technique described by Matioc et al. [13]. We used this technique as it represents an optimal first-attempt insertion method for the ProSeal [14]. Accordingly, an appropriately sized ProSeal was first loaded on to a lubricated, Portex 15-Fr, 60-cm coudetipped bougie (Smiths Medical, Dublin, OH, USA), placed straight-end first into the proximal end of the gastric drainage port until it extended approximately 20 cm from the distal edge of the device. After the patient was unresponsive to a jaw thrust, a size 3 Macintosh laryngoscope was placed gently into the mouth in order to assure that the tongue and hypopharyngeal tissues were displaced anteriorly. No attempts were made to view the epiglottis or vocal cord apparatus. With the ProSeal and bougie held as a unit in the dominant hand, the straight end of the bougie protruding from the ProSeal was inserted into the oesophagus under direct vision. The laryngoscope was then removed and the ProSeal was railroaded over the bougie into position. Once in place, the bougie was removed. The ProSeal cuff was inflated to an intra-cuff pressure of 60 cmH2O using a hand-held manometer and adequate ventilation was assessed.

All devices were inserted by one of the primary investigators (REG and AMJ), both of whom were equally experienced using both devices and insertion techniques. Insertion success was defined as device placement with observation of adequate ventilation within three attempts. One attempt was counted if the device had to be removed from the patient’s mouth during the insertion procedure. In the event of insertion failure, further airway management was at the attending anaesthesiologist’s discretion. Insertion time for the air-Q was measured from when the investigator picked up the device after induction of anaesthesia to confirmation of ventilation by end-tidal carbon dioxide tracing on the monitor. For the ProSeal, the time was measured from when the investigator began to insert the blade of the laryngoscope into the patient’s mouth to confirmation of ventilation by end-tidal carbon dioxide tracing on the monitor.

After device placement and confirmation of adequate ventilation, the airway seal pressure was tested with the patient’s head and neck in the neutral position by closing the expiratory valve and setting the fresh gas flow to 5 l.min−1; airway seal pressure was taken as the pressure at which the needle of the manometer attached to the anaesthesia circuit reached equilibration associated with an audible air leak from the oropharynx up to a maximum pressure of 40 cmH2O. Gastric insufflation was assessed by auscultation over the epigastrum during manual lung inflation and recorded as either present or not present. After devices were in place, leak-tested and secured, an investigator placed a fibreoptic bronchoscope (FB-15V, Pentax Medical, Montvale, NJ, USA) to the end of the airway tube and the relationship of the bowl of the mask to the vocal cords was graded using the view at the eyepiece as follows: 1 = full view of the vocal cords; 2 = partial view of the cords including arytenoids; 3 = epiglottis only; or 4 = other (SAD cuff, pharynx, other) [4]. Systolic, diastolic and mean arterial blood pressure, heart rate and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry (SpO2) were recorded before anaesthetic induction and at 1-min intervals over the first 5 min after device placement. At the conclusion of the case, the airway device was removed when the patient was awake enough to follow commands. The airway cuffs were left inflated during removal. After removal, the device was examined for the presence of grossly visible blood or bile. Its presence or absence was recorded and the severity of any staining was classified as mild, moderate, or severe. In the recovery area, once the patient was fully awake, the oropharynx was examined to assess for any injury. In addition, a standardised questionnaire was administered before hospital discharge and by telephone follow-up at 24 h to assess the frequency of oropharyngolaryngeal complaints. When present, complaints were graded by the patient as mild, moderate, or severe. All study data were recorded by one of the authors or a trained data collector. All patients remained unaware of their study group assignment; however, the personnel performing the study procedures and / or data collection, as well as the primary anaesthesia provider(s), were not blinded.

Our study was powered for superiority of the ProSeal over the air-Q for the primary outcome. Pilot data collected by the primary investigators (REG and AMJ) for the air-Q showed a mean (SD) seal pressure of 25 (7) cmH2O, while the ProSeal is reported to be 30 (8) cmH2O [2]. Considering a difference of 5 cmH2O to be the smallest clinically relevant difference in airway seal pressure, we calculated a standardised difference (difference divided by standard deviation) of 0.625 (5 / 8). Using the nomogram of Altman [15] for a two-sample comparison of a continuous variable, relating standardised difference, power and significance level, a total population size of 100 (50 patients per group) was determined for our study to ensure 80% power with a two-sided alpha of 0.05 to detect a 20% difference in airway seal pressures between the air-Q and ProSeal. Data analysis was performed on an intent-to-treat basis. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1.2. (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) Fisher’s exact testing was performed to analyse the study primary and secondary endpoints. Generalised estimating equations were used in the analysis of repeated measures. For all tests, statistical significance was defined as a p value < 0.05.

Results

One hundred and four patients were screened and approached for consent between 22 October 2009 and 13 April 2010. Four patients declined participation. No patient withdrew after enrolment. Fifty-two air-Qs and 48 ProSeal were placed. No differences in group baseline characteristics were found (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients undergoing anaesthesia with the air-Q or ProSeal supraglottic airway device. Values are mean (SD) or number (proportion).

| Air-Q (n = 52) |

LMA ProSeal (n = 48) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age; years | 39 (12) | 39 (14) |

| Sex; male | 28 (54%) | 25 (52%) |

| Height; cm | 175 (10) | 175 (10) |

| Weight; kg | 83 (18) | 87 (23) |

| BMI; kg.m−2 | 27 (5) | 28 (7) |

| Mallampati grade | ||

| 1 | 22 (42%) | 19 (40%) |

| 2 | 25 (48%) | 23 (48%) |

| 3 | 5 (10%) | 6 (12%) |

| 4 | 0 | 0 |

| ASA physical status | ||

| 1 | 18 (35%) | 22 (46%) |

| 2 | 29 (56%) | 23 (48%) |

| 3 | 5 (9%) | 3 (6%) |

| 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Surgery type | ||

| Orthopaedic | 50 (96%) | 45 (94%) |

| Urological | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) |

| General | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Other | 0 | 1 (2%) |

BMI, body mass index. ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

Table 2 summarises the devices’ size and performance characteristics. Devices were sized according to protocol in all patients with exception to one female patient who received a size 3 ProSeal due to her smaller size. Mean (SD) airway seal pressures for the air-Q and the ProSeal, were similar. There were no insertion or usage failures. Air-Q and pLMA insertion was rated easy in 87% vs 98% and slightly difficult in 13% vs 2% insertions, respectively (p = 0.067). Insertion time was shorter with the air-Q than with the ProSeal. Overall usefulness was rated excellent, good and fair 85%, 13% and 2% of the time when the air-Q was used and 88%, 8% and 4% of the time when the ProSeal was used (p = 0.57). Overall duration of use was similar. There were no differences in the fibreoptic view of the vocal cords. No episodes of epigastric insufflation after placement of the device or the appearance of gross bile after its removal were noted for either device. Gross blood was noted on 10 (19%) and 4 (8%) air-Qs and ProSeals after removal, respectively (p = 0.15). One patient who received an air-Q was found in the recovery area to have a lip abrasion. No oropharyngeal injuries were found in the ProSeal group.

Table 2.

Device size and performance of air-Q or ProSeal supraglottic airway device. Values are number (proportion), mean (SD) or mean (range).

| Air-Q (n = 52) |

LMA ProSeal (n = 48) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Device size | |||

| 3.5 | 25 (48%) | ||

| 4.5 | 27 (52%) | ||

| 3 | 1 (2%) | ||

| 4 | 24 (50%) | ||

| 5 | 23 (48%) | ||

| Insertion attempts | 0.11* | ||

| 1 | 44 (88%) | 47 (98%) | |

| 2 | 6 (12%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 3 | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Insertion time; s | 20 (14) | 28 (11) | < 0.0001 |

| Seal pressure; cmH2O | 30 (7) | 30 (6) | 0.47 |

| View of glottis | 0.25† | ||

| 1 | 41 (78%) | 29 (60%) | |

| 2 | 6 (12%) | 10 (21%) | |

| 3 | 1 (2%) | 6 (13%) | |

| 4 | 4 (8%) | 3 (6%) | |

| Duration of use; min | 72 (18–175) | 87 (26–183) | 0.16 |

First attempt compared with > 1 attempt.

Grade 1 and 2 glottic views compared with grades 3 and 4.

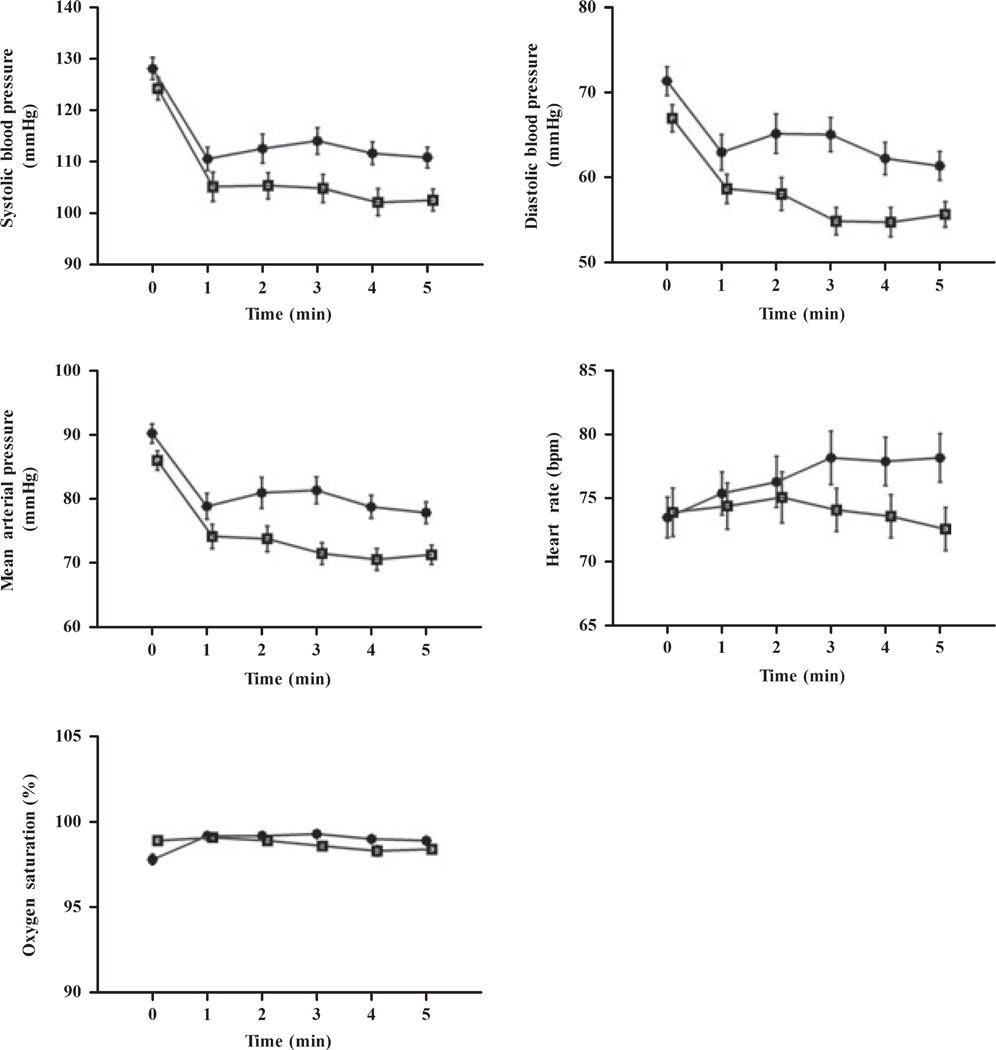

Haemodynamic and respiratory data at baseline and over the first 5 min after device placement are shown in Fig. 1. No significant changes over time were observed for heart rate and SpO2. In both the air-Q and the ProSeal groups, systolic, diastolic and mean arterial blood pressures decreased over time (p < 0.05). In addition, systolic, diastolic and mean blood pressure values were significantly higher in the air-Q group compared to the ProSeal group (p = 0.002, p < 0.0001 and p < 0.0001, respectively).

Figure 1.

Haemodynamic and respiratory characteristics after placement of the air-Q (●) and ProSeal (□). Values are mean (and for clarity, error bars are SEM).

In the recovery area, more patients in the air-Q group reported sore throat (46% vs 38%, p = 0.03). At 24-h follow-up, more patients in the air-Q group reported pain on swallowing (p = 0.01), but not sore throat (30% vs 5%, p = 0.07). The occurrence of pain in the jaw or mouth, pain on speaking, tongue swelling, tongue numbness, face numbness, lip numbness, ear pain, hearing change and vomiting in the recovery area or at 24-h follow-up were similar between devices. The presence of gross blood on the device at removal was significantly associated with sore throat pain (p = 0.04) in the recovery area, but not at 24-h follow-up.

Discussion

Our main finding is that airway seal pressures of the air-Q and ProSeal were similar. We do not believe a type-2 statistical error arose as, in a post hoc power analysis, our sample size provided > 95% power to detect a clinically relevant 5-cmH2O airway seal pressure difference between the devices. In other respects, we found the air-Q to be a satisfactory device, while providing a clear view of the vocal cords in 90% of patients, which should have facilitated fibreopticguided tracheal tube placement through the device if necessary.

The ProSeal was chosen as the comparator for our study as clinical evidence has demonstrated its ability to provide a superior airway seal pressure compared with other currently available SADs [2]. Both air-Q and ProSeal are constructed from silicone, which may conform to the supraglottic structures better than PVC, the material used for many disposable SADs, which tend to have higher airway seal pressures. Design features unique to the air-Q that are likely to improve its airway seal pressure include: (1) an anterior curve of the airway tube that better approximates the upper oropharyngeal airway and may provide a more stable end-to-end coupling with the glottis; (2) mask ridges that may improve the transverse stability of the bowl and support the lateral cuff seal; and (3) a higher posterior heel height, which may improve the seal at the base of the tongue. However, the mean airway seal pressure for the reusable air-Q may actually be higher than we observed because first, in order to avoid pulmonary complications, measurement was terminated if a pressure of 40 cmH2O was reached. This occurred in seven (13.5%) and six (12.5%) patients receiving air-Qs and ProSeals, respectively. Second, we chose to fill the air-Q cuff after insertion with 15–20 ml air in accordance with the device labelling, which may have resulted in over-inflation. Keller et al. previously demonstrated that over-inflation of the cLMA results in a decline in airway seal pressure [16]. If this holds true for the air-Q, then the mean airway seal pressure for the air-Q observed in this study may be an underestimate.

Our findings that the air-Q was easy to insert are similar to those recently reported by Bakker et al. using the earlier generation, PVC-based, single-use design in 59 generally healthy patients undergoing elective surgery [9], and are in agreement with multiple other reports in which a host of reusable and disposable laryngeal masks were used [17–28]. The insertion success is likely to proceed from the commonality of techniques and general design features of the air-Q and other SADs.

We did not assign insertion time as a primary endpoint as the additional steps required by the gum elastic bougie-guided insertion technique used for ProSeal placement would bias the results. We chose this technique to optimise placement of the control device as it represented the standard insertion technique for both primary investigators placing the study devices and has been reported to result more frequently in successful ProSeal placement on the first attempt [14]. Notably, the mean (SD) time for ProSeal insertion and first attempt success rate in our study are consistent with previously published results (25 (14) s vs 28 (11) s and 100% vs 98%, respectively) [14] and supports our choice and performance for placement of the control device.

More patients who received the air-Q reported throat compared with those receiving the ProSeal. We suspect cuff over-inflation (discussed above) was a likely factor [29, 30]. Mucosal injury occurring at air-Q insertion and / or removal may also be a contributing factor.

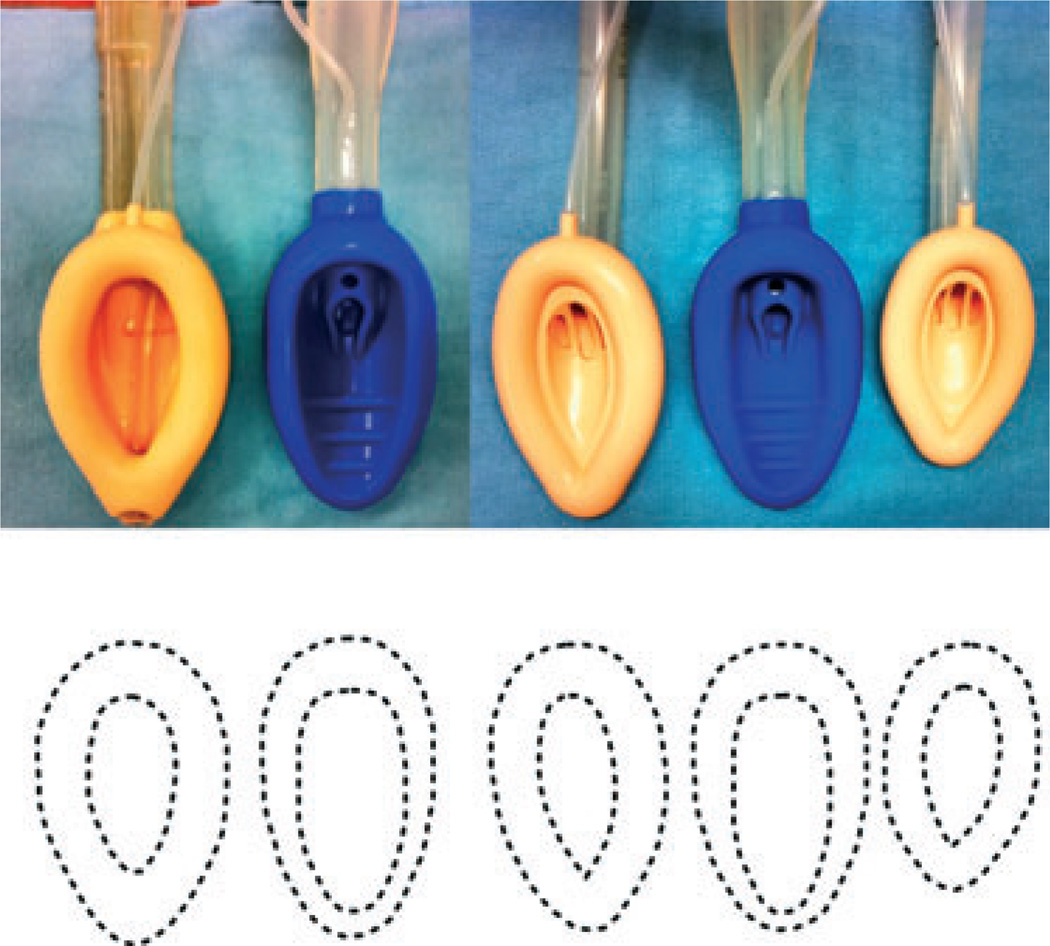

Our choice of size of device for use in each patient deserves further mention. The air-Q sizes (3.5 and 4.5) are intended to be intermediate to the familiar whole number sizes (3, 4 and 5) of other adult-sized SADs, but there are differences in the size of the periglottic portion of the mask and the bowl-to-mask ratio between the study devices (Fig. 2). We chose to follow sex-based rather than weight-based sizing for both devices [31–33].

Figure 2.

From left to right, comparison of the overall sizes and the bowl-to-cuff relationships of the size 5 LMA-Classic™, size 4.5 air-Q®, size 4 LMA-Classic™, size 3.5 air-Q® and size 3 LMA-Classic™ (top). Note the overall dimensions of the air-Q® are intermediate to the respective LMA-Classic™. This is illustrated graphically by tracing the cuff of the device from the top part of the figure (bottom).

Although we recorded the view of the glottic aperture, our study was not a comparison of the air-Q and the ProSeal as conduits for fibreoptic intubation. Two recent investigations have reported blind intubation success rates via the air-Q of up to approximately 77% with overall success (including fibreoptic-assisted intubation) success rates of up to 99% [10, 11]. This falls short of the blind and fibreoptic assisted intubation success rates via the LMA-Fastrach™ reported in the same trials, so this is an aspect of performance that warrants further study.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms Namita Azad, MPH, Research Coordinator, Office of Clinical Trials, University of Wisconsin-Madison, for her assistance in coordinating our trial.

This research was supported by intradepartmental funding and, in part, by Grant UL1RR025011 from the NIH National Center for Research Resources. Air-Q® devices were provided free of charge by the manufacturer for use in the study.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the Society for Airway Management’s Annual Meeting, Chicago, USA; September 2010.

Competing interests

None of the authors have any financial relationship with any of the device manufacturers with an interest in the subject matter of this study. Further, none of these manufacturers were involved in the design of study, study conduct, data analysis and / or manuscript preparation.

References

- 1.Asai T, Latto IP, Vaughan RS. The distance between the grille of the laryngeal mask airway and the vocal cords – is conventional intubation through the laryngeal mask airway safe? Anaesthesia. 1993;48:667–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1993.tb07175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cook TM, Lee G, Nolan JP. The Proseal™ laryngeal mask airway – a review of the literature. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 2005;52:739–760. doi: 10.1007/BF03016565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandit JJ, MacLachlan K, Dravid RM, Popat MT. Comparison of times to achieve tracheal intubation with three techniques using the laryngeal or intubating laryngeal mask airway. Anaesthesia. 2002;57:128–132. doi: 10.1046/j.0003-2409.2001.02401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danha RF, Thompson JL, Popat MT, Pandit JJ. Comparison of fibreoptic-guided orotracheal intubation through classic and single-use laryngeal mask airways. Anaesthesia. 2005;60:184–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.04045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hodzovic I, Petterson J, Wilkes AR, Latto IP. Fibreoptic intubation using three airway conduits in a mannequin – the effect of operator experience. Anaesthesia. 2007;62:591–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blair EJ, Mihai R, Cook TM. Tracheal intubation via the Classic™ and Proseal™ laryngeal mask airways – a manikin study using the Aintree Intubating Catheter. Anaesthesia. 2007;62:385–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.04994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jagannathan N, Roth AG, Sohn LE, Pak TY, Amin S, Suresh S. The new air-Q™ intubating laryngeal airway for tracheal intubation in children with anticipated difficult airway: a case series. Pediatric Anesthesia. 2009;19:618–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.02990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang D, Deng XM, Tong SY, Luo MP, Xu KL, Wei YK. Fibreoptic intubation through Cookgas intubating laryngeal airway in two children. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:1141–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.06097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakker EJ, Valkenburg M, Galvin EM. Pilot study of the air-Q intubating laryngeal airway in clinical use. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. 2010;38:346–348. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1003800217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erlacher W, Tiefenbrunner H, Kästenbauer T, Schwarz S, Fitzgerald RD. CobraPLUS and Cookgas air-Q versus Fastrach for blind endotracheal intubation: a randomised controlled trial. European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 2011;28:181–186. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e328340c352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karim YM, Swanson DE. Comparison of blind tracheal intubation through the intubating laryngeal mask airway (LMA Fastrach™) and the Air-Q™. Anaesthesia. 2011;66:185–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joffe AM, Liew EC, Galgon RE, Viernes D, Treggiari MM. The second-generation air-Q® intubating laryngeal mask for airway maintenance during anaesthesia in adults: a report of the first 70 uses. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. 2011;39:40–45. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1103900106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matioc AA, Arndt GA. Unassisted Gum elastic bougie – guided insertion of the ProSeal™ laryngeal mask airway. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:1240–1241. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200411000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brimacombe J, Keller C, Vosoba D. Gum elastic bougie-guided insertion of the ProSeal™ laryngeal mask airway is superior to the digital and introducer tool techniques. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:25–29. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200401000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altman DG. Statistics and ethics in medical research – III how large a sample? British Medical Journal. 1980;281:1336–1338. doi: 10.1136/bmj.281.6251.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keller C, Pühringer F, Brimacombe JR. Influence of cuff volume on oropharyngeal leak pressure and fibreoptic position with the laryngeal mask airway. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1998;81:186–187. doi: 10.1093/bja/81.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brimacombe J, Keller C, Morris R, Mecklem D. A comparison of the disposable versus the reusable laryngeal mask airway in paralyzed adult patients. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 1998;87:921–924. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199810000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brimacombe JR, Brimacombe JC, Berry AM, et al. A comparison of the laryngeal mask airway and cuffed oropharyngeal airway in anesthetized adult patients. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 1998;87:147–152. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199807000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brimacombe J, von Goedecke A, Keller C, Brimacombe L, Brimacombe M. The laryngeal mask airway Unique™ versus the Soft Seal™ laryngeal mask: a randomized, crossover study in paralyzed, anesthetized patients. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2004;99:1560–1563. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000133916.10017.6D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brimacombe J, Keller C. The ProSeal laryngeal mask airway. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:104–109. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200007000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Zundert AAJ, Fonck K, Al-Shaikh B, Mortier E. Comparison of the LMA-Classic™ with the new disposable Soft Seal laryngeal mask in spontaneously breathing adult patients. Anesthesiology. 2003;99:1066–1071. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200311000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook TM, Trümpelmann P, Beringer R, Stedeford J. A randomised comparison of the Portex Softseal™ laryngeal mask airway with the LMA-Unique™ during anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2005;60:1218–1225. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Francksen H, Bein B, Cavus E, et al. Comparison of LMA Unique, Ambu laryngeal mask and Soft Seal laryngeal mask during routine surgical procedures. European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 2007;24:134–140. doi: 10.1017/S0265021506001219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenberg RS, Brimacombe J, Berry A, Gouze V, Piantadosi S, Dake EM. A randomized controlled trial comparing the cuff oropharyngeal airway and the laryngeal mask airway in spontaneously breathing anesthetized adults. Anesthesiology. 1998;88:970–977. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199804000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paech MJ, Tweedie O, Stannard K, et al. Randomized, crossover comparison of the single-use SoftSeal™ and the LMA Unique™ laryngeal mask airways. Anaesthesia. 2005;60:354–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shafik MT, Bahlman BU, Hall JE, Ali MS. A comparison of the Soft Seal™ disposable and the Classic re-usable laryngeal mask airway. Anaesthesia. 2006;61:178–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao MM, Webb T, Bjorksten AR. Comparison of disposable and reusable laryngeal mask airways in spontaneously ventilating adult patients. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. 2004;32:530–534. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0403200410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sudhir G, Redfern D, Hall JE, Wilkes AR, Cann C. A comparison of the disposable Ambu® AuraOnce™ laryngeal mask with the reusable LMA Classic™ laryngeal mask airway. Anaesthesia. 2007;62:719–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brimacombe J, Holyoake L, Keller C, et al. Emergence characteristics and postoperative laryngopharyngeal morbidity with the laryngeal mask airway: a comparison of high versus low initial cuff volume. Anaesthesia. 2000;55:338–343. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2000.01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seet E, Yousaf F, Gupta S, Subramanyam R, Wong DT, Chung F. Use of manometry for laryngeal mask airway reduces postoperative pharyngolaryngeal adverse events. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:652–657. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181cf4346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asai T, Howell TK, Koga K, Morris S. Appropriate size and inflation of the laryngeal mask airway. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1998;80:470–474. doi: 10.1093/bja/80.4.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Voyagis GS, Batzioulis PG, Secha-Doussaitou PN. Selection of the proper size of laryngeal mask airway in adults. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 1996;83:663–664. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199609000-00062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berry AM, Brimacombe JR, McManus KF, Goldblatt M. An evaluation of the factors influencing selection of the optimal size of laryngeal mask airway in normal adults. Anaesthesia. 1998;53:565–570. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1998.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]