ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

A fundamental aim of primary care redesign and the patient-centered medical home is improving access to care. Patients who report having a usual site of care and usual provider are more likely to receive preventive services, but less is known about the influence of specific components of first-contact access (e.g., availability of appointments, advice by telephone) on preventive services receipt.

OBJECTIVE

To examine the relationship between number of first-contact access components and receipt of recommended preventive services.

DESIGN

Secondary survey data analysis.

PARTICIPANTS

Five thousand five hundred and seven insured adults who had continuity with a usual primary care physician and participated in the 2003–2006 round of the Wisconsin Longitudinal Survey.

MAIN MEASURES

Using multivariable logistic regression, we calculated adjusted risk ratios, adjusted predicted probabilities and 95% confidence intervals for each preventive service.

KEY RESULTS

Experiencing more first-contact access components was significantly associated with a higher rate of receiving cholesterol tests, flu shots and prostate exams but not mammography. There was variation in the number of components needed (between two and seven) to achieve a significant difference.

CONCLUSIONS

Having an increasing number of first-access components in a primary care office may improve preventive services receipt, and more components may be required for those services requiring greater provider contact (e.g., prostate exam) versus those that require less (e.g., mammography). In primary care redesign, the largest gains in preventive services receipt likely will come with redesign of multiple components simultaneously. While our study is a necessary step towards broadly understanding the relationship between first-contact access and preventive service receipt, other important questions remain. Certain components may drive greater improvements in the receipt of different services, and the effect of some of these components may depend on individual patient characteristics. Further research is critical for understanding redesign strategies that may optimize preventive service delivery.

KEY WORDS: patient-centered medical home, preventive medicine, access to care, continuity of care, primary care, health care utilization, aging

INTRODUCTION

One of the fundamental aims of primary care redesign is improving patients’ access to care, defined by the Institute of Medicine as the “timely use of personal health services to achieve the best possible outcome.”1 At a fundamental level, access to primary care involves having a usual site of primary care and a usual provider at that site of care. Having this level of access has been associated with numerous positive health outcomes including increased receipt of preventive services.2–4 Preventive services such as cancer screening, immunizations and cholesterol screening are well known to reduce premature mortality.5–10

Although having access to a usual provider and source of care has been linked to improved preventive care, less is known regarding the impact of primary care office access factors. These structural factors have been conceptualized as facilitating first-contact care, whereby patients use primary care as an entry point into the medical system.11 First-contact care encompasses the availability and accessibility of care at a primary care office, such as wait times for appointments, office hours, and the availability of advice by telephone. It is considered one of the core attributes of primary care and first-contact access is a key tenet of the patient-centered medical home.12 The few studies that have examined the impact of first-contact care on preventive services reported a positive association between preventive service receipt and the presence of the two to four components of first-contact care that were studied.13,14 What has not been examined in detail, however, is how many of these components of first-contact care are necessary to achieve this benefit. Answering this question is important to guide primary care office redesign efforts to improve outcomes including preventive care delivery.

This study was designed to increase our understanding of how many components of first-contact access are necessary to achieve a significantly higher rate of certain individual preventive services. In a sample of insured older adults who reported two or more years of continuity with the same primary care physician and office, we examined the influence of an increasing number of first-contact access components upon the receipt of four preventive health measures—cholesterol screening, influenza vaccination, mammograms and prostate screening. We also examine the most and least commonly reported first-contact access components.

METHODS

Sample

The sample was defined within the 2003–2006 rounds of the combined telephone and mail survey of the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study, a long-term cohort study of a one-third random sample (N = 10,317) of individuals who graduated from Wisconsin high schools in 1957, and 8,778 of their randomly-selected siblings. In 2003–2006, surviving participants were first interviewed by telephone. Those completing the telephone interview or those who refused the telephone interview then received a mailed survey. Numerous telephone interview attempts were made and surveys were mailed up to three times. The response rate for the telephone survey was 80% among graduates and 78% for siblings. The response rate for the mailed survey was 88% among graduates and 81% among siblings. The study has had continually high response rates due to a history of “good will” with the sample.15

We excluded those who reported no visits to a medical provider in the past 12 months (7%) and those who were uninsured (3%). We further restricted the sample to include only respondents who had evidence of an established continuity of care relationship with an individual primary care physician (59%). This relationship was defined by reporting that a respondent usually saw the same family practice or internal medicine doctor at the same facility for at least two years. The final sample consisted of 5,507 adult respondents, 91% of whom were age 60 or older. Sixty-one percent of the sample were high school graduates, who ranged in age from 62 to 68, and 39% were siblings, ages 40 to 86. The Institutional Review Board at the participating university granted approval for this study.

Variables/Measures

The primary outcome variables were yes/no questions that asked respondents to report the receipt of four preventive services in the last year. These services were chosen because they were recommended to be performed annually and thus their appropriate completion could be measured by the questions posed in the survey. Respondents were asked “In the last 12 months, have you had (1) a cholesterol test; (2) a flu shot; (3) a mammogram; and/or (4) a prostate exam?” The appropriate sample for receipt of each preventive service was determined by guidelines in place at the time of the study.16–19 Specifically, mammogram screening was examined in women aged 40 or older, and prostate screening was examined in men aged 50 or older. The receipt of annual cholesterol testing was examined in those reporting atherosclerotic vascular disease conditions (high blood pressure, coronary heart disease/myocardial infarction, circulation problems, stroke, high cholesterol) and diabetes. We examined the receipt of influenza vaccination in those aged 50 or older.

The components of first-contact access were assessed using eight items from the validated access to care subscale of the Group Health Association of America Consumer Satisfaction Survey (CSS).20 These items began with the stem, “Thinking about your own health care, how would you rate…” Areas assessed were the (1) convenience of the location of your doctor’s office (2) hours when the doctor’s office is open (3) arrangements for making appointments for medical care by phone (4) length of time spent waiting at the office to see the doctor (5) length of time waiting between making an appointment for routine care and the day of the visit (6) availability of medical information or advice by phone, (7) ease of seeing the doctor of your choice, and (8) amount of time you have with doctors and staff during a visit. The original response categories were excellent, very good, good, fair or poor. Responses of “excellent” or “very good” were considered indicative of perceiving that access in an area was satisfactory; thus, response categories were collapsed as follows: 1 = excellent/very good, 0 = good/fair/poor.

Covariates included in all models as categorical variables were age (<60, 60–64, 65–69, 70+), gender (except for models predicting prostate exams (men only) and mammography (women only)), marital status (married, separated/divorced, widowed, never married), education (high school or less, some college, college, post-graduate), total household income (<$30,000, $30,000–44,999, $45,000–59,999, $60,000–74,999, >$75,000, missing), type of health insurance (private, Medicare and other private, Medicare or other public), self-rated health (excellent/very good/good and fair/poor), a count of self-reported chronic conditions (0–1, 2, 3, >4) and self-perception of positive health behaviors. Self-perception of positive health behaviors was measured by an item that asked for agreement or disagreement with the statement “I work hard at trying to stay healthy.” Responses were dichotomized (agree strongly/agree and neutral/disagree/disagree strongly).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed in 2010 using Stata.21 First, polychoric correlations were performed to assess the relation between the individual components of first-contact accessibility. Initial descriptive analysis included percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. Multivariable logistic regression was used to calculate adjusted risk ratios, adjusted predicted probabilities and 95% confidence intervals for each preventive service. An adjusted risk ratio approach was used given its superiority to odds ratios when presenting findings from multivariable logistic regression analyses of dichotomous outcomes where the outcomes are common.22 The number of components was included in separate regression models as a continuous variable to examine the linearity of response, and then as an indicator variable to examine the effect of adding an additional component. Adjusted predicted probabilities were estimated based on the recycled predictions approach using the Stata margins command. Differences were considered statistically significant at a value of p < 0.05. Confidence intervals were calculated using a robust estimate of the variance that allowed for clustering of siblings within families.

The study’s funding sources had no role in the design, conduct, or results, nor the decision to report the data in publication.

RESULTS

Respondent characteristics of this cohort of insured individuals with an established primary care physician continuity relationship are found in Table 1. The majority of respondents were in their sixties, female, married, had a high school education or less and had a total household income greater than or equal to $45,000. Most had private health insurance, had four or more chronic conditions, rated their health as good to excellent and agreed that they worked hard to stay healthy. There were high rates of preventive service receipt among those in the sample eligible to receive each service. In the past 12 months, 90% reported receiving a cholesterol test, 63% a flu shot, 78% a prostate exam and 83% a mammogram (data not shown in table).

Table 1.

Key Demographic and Health Characteristics of 2003–2006 Wisconsin Longitudinal Study Respondents (N = 5507)

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Less than 60 | 496 (9) |

| 60-64 | 2829 (51) |

| 65-69 | 1677 (30) |

| Greater than or equal to 70 | 505 (9) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 2940 (53) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 4429 (80) |

| Separated or divorced | 470 (9) |

| Widowed | 411 (7) |

| Never married | 195 (4) |

| Educational attainment | |

| High school or less | 2963 (54) |

| Some college | 854 (16) |

| College | 807 (15) |

| Post-graduate | 831 (15) |

| Total household income ($) | |

| Less than $30,000 | 1015 (18) |

| $30,000-$44,999 | 935 (17) |

| $45,000-$74,999 | 1538 (28) |

| Greater than or equal to $75,000 | 1781 (32) |

| Missing | 238 (4) |

| Health insurance | |

| Private | 3071 (56) |

| Medicare and other private | 1886 (34) |

| Medicare or other public | 550 (10) |

| Chronic conditions* | |

| 0-1 | 812 (15) |

| 2-3 | 1852 (34) |

| 4 or more | 2843 (52) |

| Self-rated health | |

| Excellent or very good | 3403 (62) |

| Good, fair, or poor | 2076 (38) |

| Work hard to stay healthy | |

| Strongly agree or agree | 4527 (82) |

| Neutral, disagree, or strongly disagree | 963 (18) |

Due to rounding, percentages may not add to 100

*The following 22 chronic conditions were measured in this count: asthma, bronchitis/emphysema, serious back trouble, circulation problems, kidney/bladder problems, ulcer, allergies, multiple sclerosis, high blood pressure, diabetes, cancer, coronary heart disease/ myocardial infarction, stroke, arthritis, pain and stiffness in the joints, mental illness, chronic sinusitis, fibromyalgia, high cholesterol, irritable bowel syndrome, osteoporosis, and prostate problems

Variation existed in the extent that individuals perceived excellent or very good access in the eight first-contact areas (Table 2). The component that was perceived accessible by the most individuals was making appointments for care by phone (68%). The component where there was the least perceived access was the availability of medical advice and information by phone (38%). Correlation between the eight first-contact elements ranged from 0.48-0.87.

Table 2.

Percent of 2003–2006 Wisconsin Longitudinal Study Respondents (N = 5507) Reporting First-Contact Access Components*

| First-Contact Access Components | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Availability of medical advice and information by phone | 2119 (38) |

| Length of time between making an appointment and day of visit | 2343 (43) |

| Length of time spent waiting at office for the doctor | 2481 (45) |

| Amount of visit time spent with doctors and staff | 2914 (53) |

| Hours when the doctor’s office is open | 3104 (56) |

| Convenience of location of the doctor’s office | 3265 (59) |

| Ease of seeing doctor of his/her choice | 3492 (63) |

| Making appointments for care by phone | 3740 (68) |

*Presence of first-contact accessibility component defined as a rating of 4 or 5 on a 5 point scale where 1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, 5 = excellent

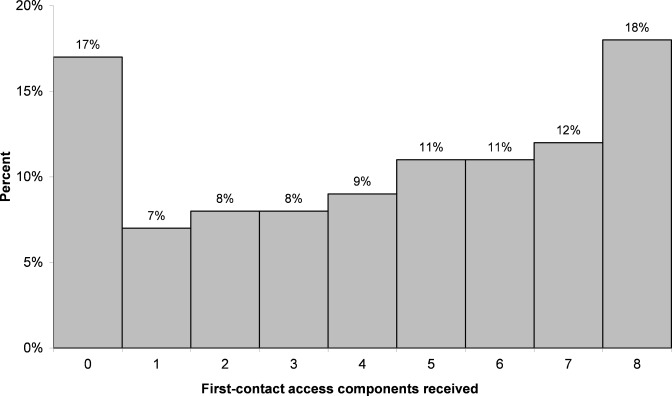

Figure 1 is a histogram showing the number of first-contact areas in which individuals perceived having very good or excellent access. An almost equivalent number (17 vs. 18 percent of the sample) perceived having access to zero and all eight components.

Figure 1.

Percent of participants receiving 0–8 first-contact access components*

* First-contact access components defined as very good or excellent ratings on the following: convenience of doctor’s location, hours of doctor’s availability, phone appointment arrangements, office wait time, time between making appointment and visit, medical advice and information availability by phone, ease of seeing doctor of choice, and amount of visit time spent with doctors and staff

As shown in Tables 3 and 4, an increasing number of first-contact access components was significantly associated with an increase rate of receiving cholesterol tests, flu shots and prostate exams. The number of components was not significantly associated with increased mammogram screening rate. There was variation in the number of components needed to achieve a significant difference for individual preventive services. After the presence of two first-contact access components, the rate of receiving a cholesterol check increased between four and seven percentage points. For flu shots, a significant increase of nine to seventeen percentage points was seen when six first-contact access components were present. Seven or more components were needed for the rate of prostate screening to significantly increase (by 12%–14%). Adjusted models that included the number of access components as a continuous variable similarly showed a significant increase in the receipt of cholesterol tests, flu shots, and prostate exams, but not mammograms (data not shown).

Table 3.

Multivariable Adjusted Risk Ratios, Predicted Probabilities, and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) for Logistic Regression Predicting Cholesterol Checks (N = 4109) and Flu Shots (N = 5399) by Number of First-Contact Access Components*†‡

| Number of first-contact access components | Cholesterol Checks | Flu Shots | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Risk Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Predicted Probability (95% CI) | Adjusted Risk Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Predicted Probability (95% CI) | |

| 0 | 1.00 (reference) | 86% (84, 89) | 1.00 (reference) | 58% (55, 61) |

| 1 | 1.03 (0.98, 1.08) | 89% (85, 92) | 0.98 (0.89, 1.08) | 57% (53, 62) |

| 2 | 1.06 (1.01, 1.10)‡ | 91% (88, 94) | 1.08 (0.98, 1.17) | 63% (58, 67) |

| 3 | 1.05 (0.996, 1.10) | 90% (87, 94) | 1.06 (0.96, 1.15) | 62% (57, 66) |

| 4 | 1.07 (1.02, 1.11)‡ | 92% (90, 95) | 1.05 (0.96, 1.14) | 61% (57, 65) |

| 5 | 1.04 (0.996, 1.09) | 90% (87, 93) | 1.08 (0.99, 1.17) | 63% (59, 67) |

| 6 | 1.04 (0.99, 1.08) | 90% (87, 93) | 1.11 (1.02, 1.20)‡ | 65% (61, 69) |

| 7 | 1.07 (1.02, 1.11)‡ | 92% (90, 95) | 1.09 (1.01, 1.18)‡ | 64% (60, 67) |

| 8 | 1.07 (1.03, 1.11)‡ | 92% (90, 94) | 1.17 (1.09, 1.25)‡ | 68% (65, 71) |

*Adjusted for age, sex, marital status, educational attainment, total household income, health insurance, chronic conditions, self-rated health, and working hard to stay healthy

†Presence of first-contact access component defined as very good or excellent ratings the following: convenience of doctor’s location, hours of doctor’s availability, phone appointment arrangements, office wait time, time between making appointment and visit, medical advice and information availability by phone, ease of seeing doctor of choice, and amount of visit time spent with doctors and staff

‡Indicates significance of p < 0.05

Table 4.

Multivariable Adjusted Risk Ratios, Predicted Probabilities, and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) for Logistic Regression Predicting Prostate (N = 2381) and Mammogram (N = 2891) Screening by Number of First-Contact Access Components*†

| Number of first-contact access components | Prostate Screening | Mammogram Screening | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Risk Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Predicted Probability (95% CI) | Adjusted Risk Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Predicted Probability (95% CI) | |

| 0 | 1.00 (reference) | 73% (69, 78) | 1.00 (reference) | 83% (79, 86) |

| 1 | 1.07 (0.97, 1.17) | 78% (73, 84) | 0.97 (0.90, 1.05) | 81% (75, 86) |

| 2 | 0.999 (0.90, 1.10) | 73% (67, 79) | 1.00 (0.93, 1.08) | 83% (78, 88) |

| 3 | 1.02 (0.91, 1.13) | 75% (68, 81) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.08) | 84% (79, 88) |

| 4 | 1.04 (0.94, 1.13) | 76% (70, 81) | 1.00 (0.93, 1.07) | 83% (78, 87) |

| 5 | 1.05 (0.96, 1.14) | 77% (72, 82) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.07) | 83% (79, 87) |

| 6 | 1.06 (0.96, 1.16) | 78% (72, 83) | 0.995 (0.93, 1.06) | 82% (78, 86) |

| 7 | 1.12 (1.03, 1.22)‡ | 82% (78, 87) | 1.02 (0.96, 1.08) | 84% (80, 88) |

| 8 | 1.14 (1.06, 1.23)‡ | 84% (80, 87) | 1.03 (0.98, 1.09) | 85% (82, 88) |

*Adjusted for age, sex, marital status, educational attainment, total household income, health insurance, chronic conditions, self-rated health, and working hard to stay healthy

†Presence of first-contact access component defined as very good or excellent ratings for the following: convenience of doctor’s location, hours of doctor’s availability, phone appointment arrangements, office wait time, time between making appointment and visit, medical advice and information availability by phone, ease of seeing doctor of choice, and amount of visit time spent with doctors and staff

‡Indicates significance of p < 0.05

We also examined detailed frequencies of each of the eight first-access components according to the number of components that individuals reported receiving (data not shown). Those who reported two first-access components were most likely to report excellent or very good access for arrangements for making appointments by phone and convenience of the location. The two components that were least accessible for individuals who reported the presence of six components were length of time waiting between making an appointment for routine care and the day of the visit and the lack of availability of medical information or advice by phone. For those who reported seven components, the least available component was medical information or advice by phone.

DISCUSSION

In this sample of insured older adults who had continuity with a primary care physician, we found that having more first-contact access components significantly increased the rate of receiving cholesterol checks, flu shots and prostate screening in the past year. There was no effect on the receipt of mammograms. A different number of first-contact access components were needed for the rate of each preventive service to significantly increase, with cholesterol checks requiring the least number of components in place, and prostate screening requiring the most. The first-access component which respondents perceived to be least accessible was the availability of medical advice and information by phone.

For preventive services where more contact with a provider was required, more first-contact access components were necessary to increase rates. The receipt of cholesterol testing, for instance, which generally just requires an open lab and a provider order, showed a significant increase after just two first-contact access components. In contrast, prostate testing, which requires an invasive exam from a provider, required seven components to show a significant increase. Primary care practices can use this information when deciding on which components of access to invest in, as some preventive services gains may be realized from smaller investments such as expanding clinic laboratory hours as compared to the larger investment of trying to incorporate all eight first-access components.

Mammograms, which are most often not obtainable at the clinic office site, were unaffected by office first-contact access components. A possible explanation for the rate of mammography being unaffected by the presence of first contact access is among the four preventive services studied, it is the one with the most visible public health promotion efforts. The need for mammography screening has been widely publicized through national campaigns such as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for Medicare National Medicare Mammography Campaign and National Breast Cancer Awareness Month. The overall mammography screening rate in our study population was quite high, lending credence to the idea that it might be factors other than first contact access to the primary care office that influence mammogram receipt. In fact, there has been a movement towards letting guideline eligible patients schedule their own mammograms independent of orders generated by a provider during office visits.23 This highlights that not all screening tasks will be equally affected by first contact access.

Our overall findings lend support to the patient-centered medical home movement, which among its many aims strives to make primary care more accessible.12 These findings suggest that a combination of initiatives to transform the delivery of primary care and to improve many aspects of first-access contact may be needed for practices to increase the receipt of several preventive services, rather than just one or two incremental changes. We found that as accessibility increased, there were gains in the receipt of certain preventive services, up to 17 percent in the case of influenza vaccination. This benefit, which was found even in our relatively affluent study population with excellent continuity of care, may translate into larger payoffs in a community setting where socioeconomic disparities would be more prevalent. Continuity of care and enhanced access to care have both independently been shown to improve receipt of preventive services in these vulnerable populations.24–26 In addition, the current national certification approach to medical homes allows for different tiers of qualification, determined by how many aspects of a medical home a practice has incorporated.27 Our findings support this approach particularly with first-contact access components. We found that the components of first-contact access to care have a dose–response effect on the receipt of several preventive services.

Our study uses a conceptual framework that implies more access points means better access, and that it is the number of access points that will be the lever for improving receipt of preventive services. This approach is warranted given that many individuals experience a cumulative burden from multiple barriers to accessing care that may be counterbalanced by multiple access points.28,29 Seventy percent of study respondents reported not receiving two or more first-access components. While our study is a necessary step towards broadly understanding the relationship between structural aspects of access in primary care clinics and preventive service receipt, there are other important questions about primary clinic first contact access and preventive service receipt that are not answerable in our data due to sample size. Certain first-contact access components may be more important than others for improving receipt of different preventive services. In addition, individual patient characteristics such as attitudes towards preventive service receipt,30,31 knowledge of preventive services,32 and chronic disease burden33 may interact with individual primary first contact access components to influence the receipt of recommended care (e.g., the effect of the amount of visit time spent with patients on mammography may be stronger for patients with lower health literacy than those with adequate health literacy). Further research into questions such as these is critical as primary care practices strive to redesign care in a way that optimizes patient-centered preventive service delivery.

Our findings should be considered in light of several additional limitations. Our sample consists primarily of older adults, and thus our findings might not be generalizable to the entire adult population. However, the screenings that we studied are indicated primarily for older individuals. In addition, our sample is limited in geographical and racial/ethnic diversity as it is drawn from individuals who attended Wisconsin high schools in the 1950s and their siblings. However, Wisconsin Longitudinal Study graduates are generally representative of the approximately 67% of Americans aged 60 to 64 who also are white non-Hispanic with a high school education.34 Another limit is our use of self-reported receipt of preventive services, which may be overestimated.35 However, there is no reason to believe any overestimation would differ between those reporting different numbers of first-contact access components. This could, though, lead to an underestimation of the effect of first contact access on preventive service receipt. Lastly, because influenza vaccination was available at other community sites during the years of the study it is difficult to know if individuals received these immunizations in their primary care clinic. These community sites, particularly pharmacies, provide the ease of a single contact, and are becoming increasingly important for the receipt of immunizations.36,37 However, this sample had a high degree of continuity with the clinic and an average number of four chronic conditions, making it likely that they would regularly be going to the clinic to receive preventive care.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that an increasing number of first-access components is significantly associated with higher rates of receipt of preventive services. Further, the number of components needed before seeing significant increases varies according to how much provider contact is necessary for a preventive service. When engaging in redesign, practices may receive small benefit from incrementally improving their availability and accessibility. However, the largest gains likely will come with comprehensive redesign of multiple access components simultaneously. Further research is needed to guide prioritizing and targeting other patient-centered medical home principles in primary care practice to maximize preventive care delivery.

Acknowledgments

Contributors

None.

Funders

This project was supported by the Health Innovation Program and the Community-Academic Partnerships core of the University of Wisconsin Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (UW ICTR) funded through an NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA), grant number 1 UL1 RR025011. In addition, Nancy Pandhi is supported by a National Institute on Aging Mentored Clinical Scientist Research Career Development Award, grant number l K08 AG029527. Dr. DeVoe’s time on this project was supported by grant number K08 HS16181 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). This project was also supported by the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center (UWCCC) Support Grant from the National Cancer Institute, grant number P30 CA014520. Additional support was provided by the UW School of Medicine and Public Health from the Wisconsin Partnership Program. This research uses data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Since 1991, the WLS has been supported principally by the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG09775, R01 AG033285), with additional support from the Vilas Estate Trust, the National Science Foundation, the Spencer Foundation, and the Graduate School of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. A public use file of data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study is available from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1180 Observatory Drive, Madison, Wisconsin, 53706 and at http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/wlsresearch/data/. The view expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Prior presentations

None.

Conflicts of interest

None disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Access to health care in America. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blewett LA, Johnson PJ, Lee B, Scal PB. When a usual source of care and usual provider matter: adult prevention and screening services. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1354–1360. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0659-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu KT. Usual source of care in preventive service use: a regular doctor versus a regular site. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:1509–1529. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.10524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saultz JW, Lochner J. Interpersonal continuity of care and care outcomes: a critical review. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:159–166. doi: 10.1370/afm.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Summaries for patients. Screening for depression in adults: U.S. preventive services task force recommendations. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151–I56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Kerlikowske K, Grady D, Rubin SM, Sandrock C, Ernster VL. Efficacy of screening mammography. A meta-analysis JAMA. 1995;273:149–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simonsen L, Reichert TA, Viboud C, Blackwelder WC, Taylor RJ, Miller MA. Impact of influenza vaccination on seasonal mortality in the US elderly population. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:265–272. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fireman B, Lee J, Lewis N, Bembom O, Laan M, Baxter R. Influenza vaccination and mortality: differentiating vaccine effects from bias. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170:650–656. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewington S, Whitlock G, Clarke R, et al. Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths. Lancet. 2007;370:1829–1839. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61778-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farley TA, Dalal MA, Mostashari F, Frieden TR. Deaths preventable in the U.S. by improvements in use of clinical preventive services. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:600–609. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forrest CB, Starfield B. The effect of first-contact care with primary care clinicians on ambulatory health care expenditures. J Fam Pract. 1996;43:40–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stange KC, Nutting PA, Miller WL, et al. Defining and measuring the patient-centered medical home. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:601–612. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1291-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bindman AB, Grumbach K, Osmond D, Vranizan K, Stewart AL. Primary care and receipt of preventive services. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:269–276. doi: 10.1007/BF02598266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeVoe JE, Fryer GE, Phillips R, Green L. Receipt of preventive care among adults: Insurance status and usual source of care. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:786–791. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.5.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauser RM, Sewell WH, Logan JA, et al. The Wisconsin Longitudinal Study: Adults as Parents and Children at Age 50. IASSIST Q. 1992;16:23–38. [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer. 5 March 2008. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/docroot/PED/content/PED_2_3X_ACS_Cancer_Detection_Guidelines_36.asp. Accessed 12 March 2008.

- 17.National Cholesterol Education Program. Detection, evaluation and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Bethesda: National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 2002.

- 18.Bridges CB, Harper SA, Fukuda K, Uyeki TM, Cox NJ, Singleton JA. Prevention and control of influenza. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2003;52(RR-8):1–36. [PubMed]

- 19.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The pocket guide to clinical preventive services 2005. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005.

- 20.Davies AR, Ware JE. GHAA’s consumer satisfaction survey and user’s manual. 2. Washington, D.C.: Group Health Association of America; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 21.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software. 11.1 ed. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2009.

- 22.Kleinman LC, Norton EC. What’s the Risk? A simple approach for estimating adjusted risk measures from nonlinear models including logistic regression. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:288–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00900.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suter LG, Elmore JG. Self-referral for screening mammography. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:710–713. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Malley AS, Mandelblatt J, Gold K, Cagney KA, Kerner J. Continuity of care and the use of breast and cervical cancer screening services in a multiethnic community. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1462–1470. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1997.00440340102010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corbie-Smith G, Flagg EW, Doyle JP, O’Brien MA. Influence of usual source of care on differences by race/ethnicity in receipt of preventive services. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:458–464. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10733.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beal AC, Doty MM, Hernandez MM, Shea KK, Davis K. Closing the divide: How medical homes promote equity in health care: Results from The Commonwealth Fund 2006 Health Care Quality Survey. Washington, D.C.: The Commonwealth Fund; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.NCQA. Standards and Guidelines for Physician Practice Connections®—Patient-Centered Medical Home (PPC-PCMH™). Washington, D.C.: National Committee for Quality Assurance; 2008.

- 28.Fiscella K, Shin P. The inverse care law: implications for healthcare of vulnerable populations. J Ambul Care Manage. 2005;28:304–312. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200510000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thorpe JM, Thorpe CT, Kennelty KA, Pandhi N. Patterns of perceived barriers to medical care in older adults: a latent class analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:181. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ajzen I. Nature and operation of attitudes. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:27–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooke R, French D. How well do the theory of reasoned action and theory of planned behaviour predict intentions and attendance at screening programmes? A meta-analysis. Psychol Heal. 2008;23:745–765. doi: 10.1080/08870440701544437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res. 1974;9:208–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fontana SA, Baumann LC, Helberg C, Love RR. The delivery of preventive services in primary care practices according to chronic disease status. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1190–1196. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.7.1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.U.S. Bureau of the Census. Educational Attainment in the United States: March 2000. Series P-20, No. 536. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office; 2000.

- 35.Fiscella K, Holt K, Meldrum S, Franks P. Disparities in preventive procedures: comparisons of self-report and Medicare claims data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:122. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singleton JA, Poel AJ, Lu PJ, Nichol KL, Iwane MK. Where adults reported receiving influenza vaccination in the United States. Am J Infect Control. 2005;33:563–570. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Westrick SC, Watcharadamrongkun S, Mount JK, Breland ML. Community pharmacy involvement in vaccine distribution and administration. Vaccine. 2009;27:2858–2863. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.02.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]