Abstract

Recent research into the placebo effect has implications for the ethics of shared decision-making (SDM). The older biomedical model views SDM as affecting which therapy is chosen, but not the nature or likelihood of any health outcomes produced by the therapy. Research indicates, however, that both the content and manner in which information is shared with the patient, and the patient’s experience of being involved in the decision, can directly alter therapeutic outcomes via placebo responses. An ethical tension is thereby created between SDM aimed strictly and solely at conveying accurate information, and “outcome engineering” in which SDM is adapted toward therapeutic goals. Several practical strategies mitigate this tension and promote respect for autonomous decision-making while still utilizing the therapeutic potential of SDM.

INTRODUCTION

Peabody’s classic 1927 paper, “The Care of the Patient,” argued ahead of its time that science shows an association between psychosocial factors and disease.1–3 The placebo and nocebo effects exemplify this association.4,5 Despite homage to Peabody’s eloquence, 20th century American medicine largely ignored or derided the placebo effect. Recently, the science of the placebo has achieved greater (if still grudging) acceptance.4,6 Patients’ expectations can alter the course of illness, and surveys indicate that physicians often prescribe medications to promote placebo effects.7–9 It is time to apply these findings to the ethics of shared decision-making (SDM), especially given SDM’s inclusion in the Affordable Care Act of 2010.10

The term SDM is often used inconsistently.11,12 The following elements characterize our understanding of SDM13–18:

Physician and patient both actively share information

The physician actively explores the patient’s values and preferences

The physician assists the patient in selecting the best option through supportive conversation

The physician is guided by the patient’s preferences both in how much information to share, and how much to involve the patient in the decision process

The physician ultimately respects the patient’s right to make the decision

SDM may (and should) be employed in life-threatening disease, where biomedical factors far outweigh placebo effects in determining the outcome. Nevertheless, physicians frequently encounter treatment decisions involving chronic and self-limited illnesses. In these latter cases, SDM’s role in promoting therapeutic placebo effects assumes greater importance.

Two Models of SDM’s Impact on Patient Outcomes

SDM is generally interpreted according to a biomedical model. The SDM process starts with the scientific data on the nature and likelihood of the benefits and harms associated with each treatment. The physician explains these facts and then assists the patient in choosing the option that seems most in accord with her values. SDM helps the patient choose one treatment or another, which then acts on the patient’s body by a purely materialistic mechanism, independent of the SDM process.

Consider a patient with chronic low back pain. SDM requires that the physician explain the many treatment options, including perhaps surgery, medications, physical therapy, massage, and acupuncture. The patient, guided by the physician to the extent that the patient wishes, then chooses a treatment option (e.g., acupuncture). Any relief the patient receives from acupuncture is attributed either to its physiological properties or to placebo effects. The SDM process itself is presumed to have no role in determining the outcome.

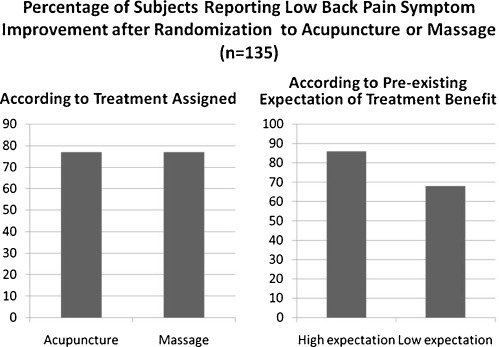

This biomedical model neglects recent findings about placebo effects. Consider for example a study by Kalauokalani et al. comparing acupuncture to massage for back pain.19 After eliciting subjects’ expectancies regarding the efficacy of both modalities, investigators randomly assigned the subjects to one of these two treatments. Overall, there was no difference in outcomes between the acupuncture and massage groups. But there was a significant and clinically important difference between the high-and low-expectancy groups—subjects administered the treatment they believed was best for back pain, whether massage or acupuncture, had outcomes superior to those given the opposite treatment (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Data summarized from Kalauokalani et al,.19 matched vs. mismatched expectancies and therapeutic response to massage or acupuncture in low back pain.

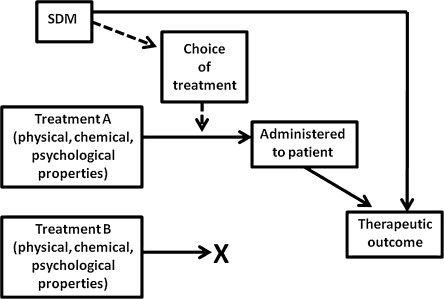

In an expanded model of SDM (Fig. 2), the SDM process can powerfully shape the patient’s emotions and beliefs, which in turn can influence the therapeutic outcome. Consider a physician about to recommend massage, but SDM elicits the patient’s belief that acupuncture would be better. The physician might then alter the recommendation, arguing that the patient is more likely to respond well to acupuncture. Alternatively, the physician could explain in more detail why she is recommending massage. The discussion might change the patient’s belief, shifting from uninformed to better informed preferences, and thus contribute to an improved outcome from massage.

Figure 2.

Expanded model of SDM. Solid arrows denote presumed causal connections.

The Scientific Base for the Expanded Model

Extensive research, which we only briefly summarize here, supports the expanded model of SDM.20 Patient participation in treatment decisions as part of a “sustained partnership” with the physician improves health outcomes to a degree not fully explained merely by better adherence to treatment.21–24 Outcomes affected range from emotional well-being and improved function to symptom relief and altered physiological measures.25,26

Placebo effects operate on different diseases and organ systems by activating different neurochemical pathways.4,7 Both cognitive and affective brain areas participate in these neurochemical processes in an overlapping and interactive manner. One area of research that illuminates the clinical significance of placebo effects is hidden vs. open administration of medication. Experiments involving medications for pain, anxiety, and Parkinson’s disease reliably demonstrate approximately twice the symptomatic relief when patients see medication injected intravenously, compared with administration of the same medication by a concealed, pre-programmed infusion pump.27 The patient’s knowledge of and psychological reaction to the medication appear to be as important as its chemical properties in producing the desired outcome. Supportive, empathic communication with the physician further enhances therapeutic results.28

While we have focused on positive placebo effects, the nocebo effect—undesired outcomes resulting from the patient’s negative expectations—also has important implications for SDM.4,5 Communications about adverse effects of treatments may affect the likelihood of these reactions.

Ethical Implications for SDM

The expanded model of SDM raises several ethical questions:

How much of the scientific evidence must be discussed with patients? Should patients be told, for example, that a treatment recommendation is based only on level B evidence rather than level A?

Should we tell patients that their mental states could account for treatment outcomes, when the “bare” treatment (in pharmacological or physiological terms) may have little or no efficacy?

Is it legitimate to manipulate the SDM process to maximize placebo reactions, stretching or even abandoning truthful disclosure? How much and what kind of “spin” is permissible in describing treatment options to stimulate healing?29

Negotiation and transparency in SDM help to address these ethical concerns to promote both autonomy and therapeutic benefit.

Negotiation and Transparency

Ideally, patients are involved in making decisions on two levels.30 The decision we generally focus on is a specific choice among alternative treatments. But these decisions are lower-level exercises of SDM that ideally should reflect a prior higher-level decision. Higher-level SDM is a negotiation over the patient–physician relationship—to what degree the patient wishes to be informed, how much the patient desires the physician to interject her own values into the discussion, and so on. In short, the patient decides where to locate this relationship on a spectrum between physician as neutral information purveyor and physician as trusted counselor.31

Higher-level negotiation could address the ethical question of “spin.” The patient, for example, might agree that the physician add optimistic spin to later therapeutic discussions but not conceal critical evidence or deceive the patient. The patient could later ask for additional details if she suspected that spin was interfering with her rational choice among treatments.

Transparency—the physician’s thinking out loud about therapeutic choices—is another tool that may enhance the ethical use of SDM. Transparency is generally a helpful strategy for incorporating SDM smoothly into the flow of the typical patient encounter.32,33 Exactly how transparent a discussion ought to be to achieve placebo-related “boost” in treatment is a matter for research and careful judgment. But the following statement seems ethically justified as well as likely to be therapeutically effective:

Science shows that we have built-in chemical responses that help make medicines and other treatments work better. My job is to work with you to turn on those powerful inner forces. How can we apply this to your back pain? One thing that turns on those powerful inner chemicals is your belief that a treatment will work, and your picking the treatment in which you have the greatest confidence. I sense that you have a lot of faith in acupuncture. So acupuncture could give you the best of both worlds, the potential benefits from the needles plus that extra boost from your own confidence.

By being transparent about promoting placebo effects, the physician invites more questions from skeptical patients, and avoids using deception to secure benefit. Many assume that honest disclosure would negate placebos’ therapeutic potential. However, irritable bowel syndrome patients randomized to receive open-label placebo pills and told that such pills often relieve symptoms through a “mind-body self-healing process” experienced more relief than no-treatment controls.34 Thus disclosure of the physician’s goal of enhancing the placebo response may be perceived by the patient as a positive “pep talk” and actually augment the placebo reaction by reinforcing positive expectations.

Transparency and negotiation both help determine how much scientific evidence to share with each patient. Even if the difference between level A and B evidence seems purely technical, physicians can give patients a general sense of whether a recommendation is strongly or weakly supported. Moreover, the physician as health educator should convey some rudiments of evidence-based medicine to patients as part of routine care. That understanding will help patients to be realistic about the uncertainties of medical interventions. Negotiation may reveal which patients wish to know more about the evidence, and physicians limited in either time or knowledge may refer patients to resources such as internet sites. The further development of interactive decision aids will assist interested patients in understanding the evidence.

Further Ethical Recommendations

Negotiation and transparency illustrate how some degree of outcome engineering is both permissible and desirable on the expanded SDM model. As with acupuncture for back pain, physicians will generally be most justified in recommending a treatment primarily for its placebo properties when evidence shows the modality is associated with a pronounced placebo response and when the risk of adverse reactions is low. Nevertheless, considerable judgment is needed, partly because such evidence exists for very few modalities today. As Kalauokalani et al. show, the likelihood of a placebo response may depend on individual expectancies which cannot be discerned from population averages.19

Outcomes engineering may help prevent nocebo effects.5,35 In a study of influenza immunization, those told that 5% of patients suffered reactions ended up reporting more side effects than those told that 95% would suffer no such reactions.36 Since both disclosures were logically equivalent, it seems reasonable to encourage the framing that produces the better therapeutic outcome.37

Outcomes engineering risks indirectly leading to false patient beliefs. Since many patients are firmly wedded to the traditional biomedical model, they may conclude incorrectly that a treatment that works must have done so due to its pharmacological or physiological properties rather than via placebo effects. Whether such false beliefs would arise, when physicians practice transparency to avoid this result, requires further research. We suggest that the physician who has exercised due care to frame information in a positive but truthful way should not be held responsible for any false beliefs that occur.

Information disclosure is always selective, and different physicians convey the same information differently. Thus outcome engineering is unavoidable. Physicians should become self-conscious about the engineering process and promote optimal outcomes while respecting patient autonomy. Further research is needed to guide physicians in achieving these goals.

CONCLUSION

Placebo and nocebo effects can result from any aspect of the medical encounter and are not exclusively tied to SDM. We have focused on SDM because of its ethical importance and because its role in eliciting these effects has commonly been ignored.

As Peabody understood in 1927, unless the science of medicine is fully deployed to elucidate and contribute to the art of medicine, medicine suffers as both a science and an art.1,3 Incorporating placebo and nocebo effects, the expanded model of SDM allows us to reintegrate the art and science of medicine for the ultimate benefit of patients.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to several anonymous reviewers for their detailed and helpful comments. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the National Institutes of Health, the Public Health Service, or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Funding Source

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Peabody FW. The care of the patient. J Am Med Assn. 1927;88:877–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.1927.02680380001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrington A. The cure within: a history of mind-body medicine. New York: Norton; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129–36. doi: 10.1126/science.847460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benedetti F. Placebo effects: understanding the mechanisms in health and disease. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hahn RA. The nocebo phenomenon: scope and foundations. In: Harrington A, editor. The placebo effect: an interdisciplinary exploration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1997. pp. 56–76. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guess HA, Kleinman A, Kusek JW, Engel LW. The science of the placebo: toward an interdisciplinary research agenda. London: BMJ Books; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colloca L, Miller FG. Role of expectations in health. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24:149–155. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328343803b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tilburt JC, Emanuel EJ, Kaptchuk TJ, et al. Prescribing ‘placebo treatments’: results of national survey of US internists and rheumatologists. BMJ. 2008; 337:a1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Kermen R, Hickner J, Brody H, Hasham I. Family physicians believe the placebo effect is therapeutic but often use real drugs as placebos. Fam Med. 2010;42:636–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Title III, Subtitle F. Sec. 3506. Program to facilitate shared decisionmaking. http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Patient_Protection_and_Affordable_Care_Act/Title_III/Subtitle_F#SEC._936._PROGRAM_TO_FACILITATE_SHARED_DECISIONMAKING. (accessed December 19, 2011).

- 11.Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60:301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moumjid N, Gafni A, Brémond A, Carrère MO. Shared decision making in the medical encounter: are we all talking about the same thing? Med Decis Making. 2007;27:539–546. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07306779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinstein JN, Clay K, Morgan TS. Informed patient choice: patient-centered valuing of surgical risks and benefits. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:726–730. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moulton B, King JS. Aligning ethics with medical decision-making: the quest for informed patient choice. J Law Med Ethics. 2010;38:85–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2010.00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Connor AM, Wennberg JE, Legare F, et al. Toward the tipping point: decision aids and informed patient choice. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:716–725. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Making health care decisions. Part 1: Report. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1982:31.

- 17.Faden RR, Beauchamp TL. A history and theory of informed consent. New York: Oxford University Press; 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katz J. The silent world of doctor and patient. New York: Free Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalauokalani D, Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, et al. Lessons from a trial of acupuncture and massage for low back pain: patient expectations and treatment effects. Spine. 2001;26:1418–24. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200107010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brody H, Miller FG. Lessons from recent research about the placebo effect—from art to science. JAMA. 2011;306:2612–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenfield S, Kaplan S, Ware JE. Expanding patient involvement in care: effects on patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:520–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-4-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leopold N, Cooper J, Clancy C. Sustained partnership in primary care. J Fam Pract. 1996;42:129–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blasi Z, Harkness E, Ernst E, et al. Influence of context effects on health: a systematic review. Lancet. 2001;357:757–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crow R, Gage H, Hampson S, et al. The role of expectancies in the placebo effect and their use in the delivery of health care: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 1999;3(3):1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152:1423–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Street RL, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colloca L, Lopiano L, Lanotte M, Benedetti F. Overt versus covert treatment for pain, anxiety and Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:679–84. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00908-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaptchuk TJ, Kelley JM, Conboy LA, et al. Components of the placebo effect: randomized controlled trial in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ. 2008;336:999–1003. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39524.439618.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller FG, Colloca L. The placebo phenomenon and medical ethics: rethinking the relationship between informed consent and risk-benefit assessment. Theor Med Bioeth. 2011; doi:10.1007/s11017-011-9179-8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Green JA. Minimizing malpractice risks by role clarification. The confusing transition from tort to contract. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:234–41. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-3-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emanuel EJ. Emanuel LL Four models of the physician-patient relationship. JAMA. 1992;267:2221–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03480160079038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brody H. Transparency: informed consent in primary care. Hastings Cent Rep. 1989;19(5):5–9. doi: 10.2307/3562634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurz-Milcke E, Gigerenzer G, Martignon L. Transparency in risk communication: graphical and analog tools. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1128:18–28. doi: 10.1196/annals.1399.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaptchuk TJ, Friedlander E, Kelley JM. Placebo effect without deception: a randomized controlled trial in irritable bowel syndrome. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(12):e15591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colloca L, Miller FG. The nocebo effect and its relevance for clinical practice. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:598–603. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182294a50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Connor AM, Pennie RA, Dales RE. Framing effects on expectations, decisions, and side effects experienced: the case of influenza immunization. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1271–76. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00177-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferguson E, Gallagher L. Message framing with respect to decisions about vaccination: the roles of frame valence, frame method and perceived risk. Br J Psychol. 2007;98:667–80. doi: 10.1348/000712607X190692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]