Abstract

We previously provided evidence that cadherin-6B induces de-epithelialization of the neural crest prior to delamination and is required for the overall epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT). Furthermore, de-epithelialization induced by cadherin-6B was found to be mediated by BMP receptor signaling independent of BMP. We now find that de-epithelialization is mediated by non-canonical BMP signaling through the BMP type II receptor (BMPRII) and not by canonical Smad dependent signaling through BMP Type I receptor. The LIM kinase/cofilin pathway mediates non-canonical BMPRII induced de-epithelialization, in response to either cadherin-6B or BMP. LIMK1 induces de-epithelialization in the neural tube and dominant negative LIMK1 decreases de-epithelialization induced by either cadherin-6B or BMP. Cofilin is the major known LIMK1 target and a S3A phosphorylation deficient mutated cofilin inhibits de-epithelialization induced by cadherin-6B as well as LIMK1. Importantly, LIMK1 as well as cadherin-6B can trigger ectopic delamination when co-expressed with the competence factor SOX9, showing that this cadherin-6B stimulated signaling pathway can mediate the full EMT in the appropriate context. These findings suggest that the de-epithelialization step of the neural crest EMT by cadherin-6B/BMPRII involves regulation of actin dynamics via LIMK/cofilin.

Keywords: EMT, Cadherin-6B, BMP, Non-canonical, LIMK, Cofilin, Neural Crest

INTRODUCTION

The epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) is an important biological process for normal embryonic development and for pathological processes, such as the formation of the neural crest and fibrosis and tumor invasion, respectively (Yang and Weinberg, 2008). Cadherins have essential roles in the development of epithelial junctions and polarity and regulate the EMT in a variety of tissues (Gumbiner, 2005). In the classical view, epithelial cells undergoing the EMT lose cell-cell adhesion caused by decrease of E-cadherin expression and gain motility (Yang and Weinberg, 2008). Cadherins are linked in some way to cortical actin to develop the polarized adherens junction (Adams et al., 1996; Kwiatkowski et al., 2010; Perez-Moreno et al., 2003). The regulation of cellular adherens junctions and dynamics of actin cytoskeleton is therefore important for the EMT.

The EMT of the neural crest is divided into at least two steps, de-epithelialization and delamination (Park and Gumbiner, 2010). Cadherin-6B, a homolog of human cadherin 6, is a Type II cadherin which is a component of cell adherens junctions (Patel et al., 2006). Although it has been shown that loss of cadherins is often required for the EMT (Yang and Weinberg, 2008) we have reported that cadherin-6B expression actually promotes the neural crest EMT (Park and Gumbiner, 2010). An alternate view, that cadherin-6B inhibits the EMT and must be repressed by snail genes, has been reported for cranial neural crest (Coles et al., 2007; Taneyhill et al., 2007). However, we found that cadherin-6B is expressed in the early migratory neural crest cells in the trunk region that have undergone delamination as well as in the trunk premigratory neural crest cells. In contrast, expression of N-cadherin protein is lost in the cadherin-6B expressing neural crest. We found that cadherin-6B induces de-epithelialization of the neural crest, which is the first step in the overall EMT (Park and Gumbiner, 2010), but N-cadherin inhibits the overall EMT of the neural crest (Park and Gumbiner, 2010; Shoval et al., 2007). Moreover, induction of de-epithelialization of the neural crest by cadherin-6B is mediated by bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) receptor signaling independently of BMP protein itself (Park and Gumbiner, 2010).

BMPs are members of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) family and play important roles in the development of embryos and organs, the differentiation of stem cells, and the regeneration of wounded tissues. Signaling by TGF-β family members can be transduced both by Smad dependent (canonical) and Smad independent (non-canonical) pathways (Derynck and Zhang, 2003; Massague, 2008). In the canonical pathway, BMP ligand induces a formation of heterodimer receptor complex, which is composed of the Type I BMP receptor (BMPRI) and the Type II BMP receptor (BMPRII). Within that complex, BMPRII activates BMPRI through phosphorylation. The active BMPRI phosphorylates Smads 1/5/8, which are released from BMPRI and in a complex with Smad4 enter nucleus in order to regulate the transcription of BMP target genes (Shi and Massague, 2003).

In order to transduce non-canonical BMP signaling, various proteins, such as JNK, Trb3, Src, and LIM kinase 1 interact with the long cytoplasmic region of BMPRII (Chan et al., 2007; Foletta et al., 2003; Lee-Hoeflich et al., 2004; Podkowa et al., 2010; Wong et al., 2005). BMPRII has a unique long cytoplasmic region, which is not present in other Type II receptor for TGFβ family proteins (Nishihara et al., 2002; Rosenzweig et al., 1995). The mediators of non-canonical BMP signaling regulate cellular processes such as cell growth (Wong et al., 2005), differentiation (Chan et al., 2007), the stabilization of microtubules (Podkowa et al., 2010), and the regulation of actin dynamics (Foletta et al., 2003; Lee-Hoeflich et al., 2004). The EMT has also been shown to be regulated by non-canonical TGFβ signaling mediated by its Type II receptor (Ozdamar et al., 2005). Direct phosphorylation of Par6 by TGFβ Type II receptor is required for TGFβ dependent EMT of mammary gland epithelial cells. Since BMP signaling mediates cadherin-6B induced de-epithelialization, the first step of the overall EMT of the neural crest, we wished to determine the nature of the intracellular BMP signaling pathway that mediates de-epithelialization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chicken embryos

Fertilized chicken (Gallus gallus) eggs (Charles River Laboratories, North Commons, CT) were incubated at 38°C in a humidified incubator (G.Q.F Manufacturing Co., Savannah, GA, USA). Embryos were staged according to the number of somite pairs.

Tissue preparation and immunohistochemistry

Tissue preparation and immunohistochemistry were performed as described (Park and Gumbiner, 2010). The trunk portion of fixed embryos (between the levels of the front and hind limb buds) was dissected out and sectioned serially at 12 – 14μm. The collected serial sections distributed over 10 slides. The immunohistochemistry of cryosections was carried out with the primary antibodies against following proteins; MSX1/2 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB), 1:300), ZO-1 (Zymed, 1:500), N-cadherin (Zymed, 1:500), cadherin-6B (DSHB, 1:200), laminin (Sigma, 1:500), HNK-1 (hybridoma producing primary monoclonal antibody supernatant from The American Type Culture Collection, 1:50), HA (Covance, 1:500/Santa Cruze, 1:200), p-cofilin (Rabbit4321, gift from James Bamburg, 1:300). The following secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes) were used at a 1:1000 dilution: anti-mouse IgG-Alexa 546, anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa 546, anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa 633, and anti-mouse IgM-Alexa-546. When required, TO-PRO-3 (Molecular Probes) was used for nucleus staining. For immunohistochemistry of phosphorylated cofilin, embryos were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes. Images were collected using a Nikon Eclipse TE2000 confocal microscope.

Electroporation and DNA constructs

DNA constructs were prepared and electroporation was carried out as described (Park and Gumbiner, 2010). Fifteen to eighteen somite pair stage embryos were electroporated with following cDNAs which were cloned into the pCIG vetor containing IRES-nlsGFP or the vector, pCAGGS-IRES-mGFP; cadherin-6B, glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol (GPI)-cadherin-6B (Park and Gumbiner, 2010), BMP4, Noggin, SOX9, Smad6, full length/short BMP Type II receptor (gift from Liliana Attisano, University of Toronto), wildtype/dominant negative LIMK1 (gift from Ora Bernard, St Vincent Institute of Medical Research), constitutively active BMP Type I A/B receptor (gift from Jane E. Johnson, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center), wildtype/S345A/S345E Par6 (gift from Michael D. Ehlers, Duke University Medical Center), and wildtype/S3A cofilin-1-HA (gift from Ian Macara, University of Virginia).

Western blot analysis

After electoporation of DNA constructs, the efficiency of electroporation was checked by GFP expression in the neural tube of embryos. The trunk part of embryos (between front limbs and hind limbs) was dissected out and the neural tube was dissected away form surrounding tissue such as somites. After washing the neural tube with phosphate buffered saline including 1mM CaCl2, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), and a mixture of phosphatase inhibitors (calbiochem), the dissected tissue was collected in RIPA buffer including protease inhibitor cocktail and a mixture of phosphatase inhibitors. The tissue and solution were drawn in and out of a 200μL pipette several times to homogenize cells. 5X SDS buffer was directly added into the extract and the extract was completely denatured with boiling at 95c° for 10 min. Then, Western blotting was performed using standard procedures. Tissue collected from at least 2 embryos was used for analysis of each experimental group. Antibodies against phosphorylated Smad1/5/8 (Cell Signaling Technology) and α-tubulin (Sigma) were used for immunoblotting.

Quantitative analysis of de-epithelialization

For quantitative analysis, we analyzed the sections exhibiting high electroporation efficiencies. The elecroporation efficiency was determined by GFP expression, because the electroporated DNA constructs have IRES-GFP. For the quantification of de-epithelialization, we measured percentage of sections exhibiting de-epithelialization in all analyzed sections of an embryo. We analyzed 7 – 28 sections per embryo. Data were presented as averages ± standard deviation and the Student’s t-test was performed to determine significance of differences. The criterion for de-epithelialization was the appearance of greater than half of GFP expressing cells inside of the lumen of the neural tube.

RESULTS

Cadherin-6B induced de-epithelialization is mediated by non-canonical BMP signaling

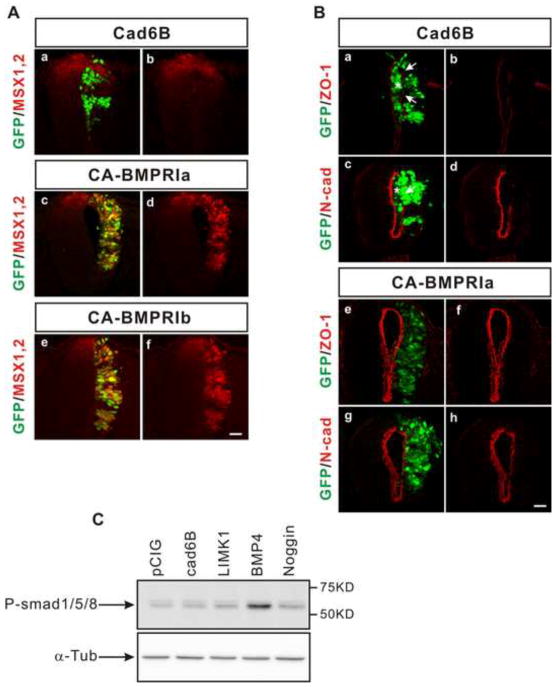

In the neural tube, cadherin-6B induces de-epithelialization, which is mediated by BMP signaling (Park and Gumbiner, 2010). BMP signaling can be transduced either through the canonical pathway dependent on transcriptional regulation by Smads or through the non-canonical pathway independently of transcriptional regulation by Smads (Massague, 2008; Miyazono et al., 2010). To ask whether cadherin-6B induced de-epithelialization is mediated by canonical or non-canonical BMP signaling, we examined the expression of downstream target genes of canonical BMP signaling, MSX1/2 (Timmer et al., 2002). Ectopic cadherin-6B expression induced de-epithelialization (Park and Gumbiner, 2010) (figure 1Ba-d), but not MSX1/2 expression in the neural tube (figure 1Aa,b). The cadherin-6B overexpressing neural tube half lost polarized tight junctions and adherens junctions at the lumen as assessed by the distribution of ZO-1 (figure 1Ba,b) or N-cadheirn (figure 1Bc,d), respectively. Also, GFP positive cells accumulated within the lumen of the neural tube (figure 1Ba–d). However, MSX1/2 remained normally expressed only in the dorsal region of the neural tube regardless of the ectopic cadherin-6B in the lateral regions (figure 1Aa,b). In addition, we performed Western blot analysis of phosphorylated Smad1/5/8 (P-Smads) with electroporated embryos in order to observe whether cadherin-6B activates canonical BMP signal. Ectopic BMP4 induced phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8 in the electroporated embryos (figure. 1C). However, ectopic cadherin-6B did not change the level of P-Smads, comparing to control electroporation (pCIG) (figure. 1C). Moreover, neither knock-down of cadherin-6B (shRNA of cadherin 6B) nor functional inhibition of cadherin-6B (dominant negative cadherin-6B) in the dorsal neural tube impaired endogenous MSX1/2 proteins expression (figure. S1). It is known that constitutively active BMP type I receptors can activate canonical BMP signaling in the neural tube independently of BMP ligand (Timmer et al., 2002). Indeed, ectopic expression of the constitutively active BMP type I receptor A or B induced MSX1/2 in the neural tube (figure 1Ac-f). However, epithelial polarity, judged by ZO-1 or N-cadherin distribution or by cell accumulation in the lumen, was not disrupted by the constitutively active BMP type I A receptor (figure 1Be-h). Therefore, canonical BMP signaling is not sufficient to induce de-epithelialization, and de-epithelialization induced by cadherin-6B does not appear to activate canonical BMP signaling.

Figure 1. Canonical signaling via BMP type I receptor does not mediate de-epithelialization.

(A) MSX1/2 are induced by ectopic expression of constitutively active BMP type I receptor, but not cadherin-6B. Both the constitutively active BMP Type I receptor A (CA-BMPRIa) (n=13 embryos, c,d) and the constitutively active BMP Type I receptor B (CA-BMPRIb) (n=5 embryos, e,f) induce MSX1/2 (red) expression, in contrast to cadherin-6B (Cad6B, n=5 embryos, a,b). (B) Ectopic expression of constitutively active BMP Type I receptor does not induce de-epithelialization. Ectopic cadherin-6B (Cad6B, n=9 embryos) disrupts the polarized distribution of ZO-1 (red, a,b) and N-cadherin (N-cad, red, c,d), but ectopic CA-BMPRIa does not (n=13 embryos, e–h). Arrows indicate disruptions in the polarized distribution of ZO-1 (Ba) or N-cad (Bc) and asterisks indicate transfected (GFP positive) cells which accumulate inside of the lumen of the neural tube (Ba,c). Construct for cadherin-6B, CA-BMPRIa, or CA-BMPRIb have an IRES-GFP (green) to mark the transfected cells. Scale Bar: 25μm. (C) Ectopic cadherin-6B does not induce phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8. Western blot of phosphorylated Smad1/5/8 (P-smad1/5/8) was performed with embryos that were respectively electroporated with cadherin-6B (cad6B), LIMK1, BMP4, Noggin, or control construct (pCIG), respectively. Alpha-tubulin (α-Tub) is an internal control for Western blot of P-Smads. The phosphorylation level of Smad1/5/8 is upregulated only in response to BMP4. Quantification of the gel bands, normalized to the alpha-tubulin loading controls, indicate values relative to the pCIG control (1.0), ectopic cadherin-6B (1.2) or LIMK1 (1.6), Noggin (1.7), and BMP4 (4.8).

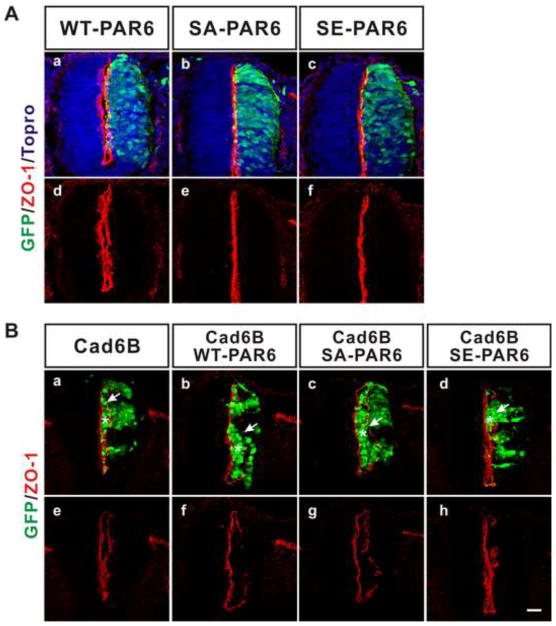

BMP signaling can be transduced through a non-canonical pathway mediated by the BMP Type II receptor (BMPRII) as well as canonical pathway. Non-canonical signaling could either be mediated by a pathway common to all TGFβ family Type II receptors, or by a specific BMPRII pathway, since the cytoplasmic tail of BMPRII is unique among TGFβ family Type II receptors. A recent study showed that TGFβ signaling mediates the EMT through non-canonical signaling involving the Type II receptor (Ozdamar et al., 2005). In this pathway, the Type II receptor phosphorylates Par6 and enhances the formation of Par6/Smurf1 complex, which disrupts tight junctions through the localized degradation of RhoA. Importantly, S345A Par6, a phosphorylation deficient mutant of Par6, was found to inhibit TGF dependent EMT (Ozdamar et al., 2005). In contrast, S345A Par6 did not block the effects of cadherin-6B (figure 2). Therefore, a different pathway, perhaps one specific to the BMPRII, may be involved.

Figure 2. De-epithelialization induced by cadherin-6B is not mediated by Par6, which is required for TGFβ dependent EMT.

(A) The polarity of ZO-1 is not disrupted by wildtype Par6 (n=3 embryos, a,d), S345A Par6 (a phosphorylation deficient mutant of Par6, n=3 embryos, b,e), or S345E Par6 (a phosphorylation-mimic mutant of Par6, n=3 embryos, c,f). Nuclei were stained blue by To-Pro-3 (a–c). (B) De-epithelialization induced by cadherin-6B was not affected by phosphorylation at Ser345 of Par6. ZO-1 is stained by red and the transfected cells are marked by IRES-GFP (green). Arrows indicate disruptions in the polarized distribution of ZO-1 and asterisks indicate transfected cells which accumulate inside of the lumen of the neural tube (a–d). Cadherin-6B (n=4 embryos), cadherin-6B/WT-PAR6 (n=3 embryos), cadherin-6B/SA-PAR6 (n=3 embryos), cadherin-6B/SE-PAR6 (n=3 embryos), Scale bar: 25μm.

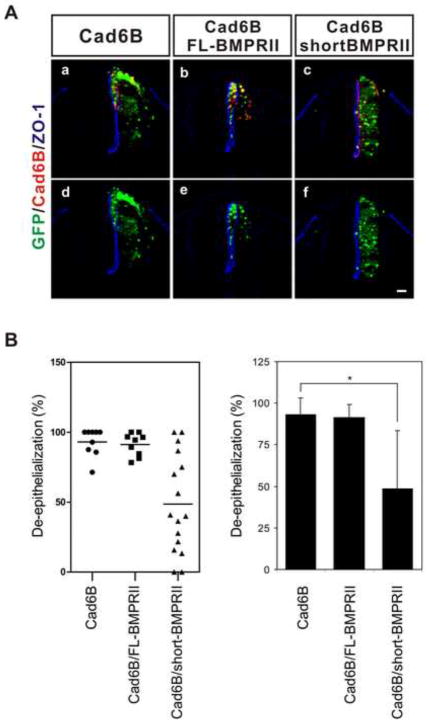

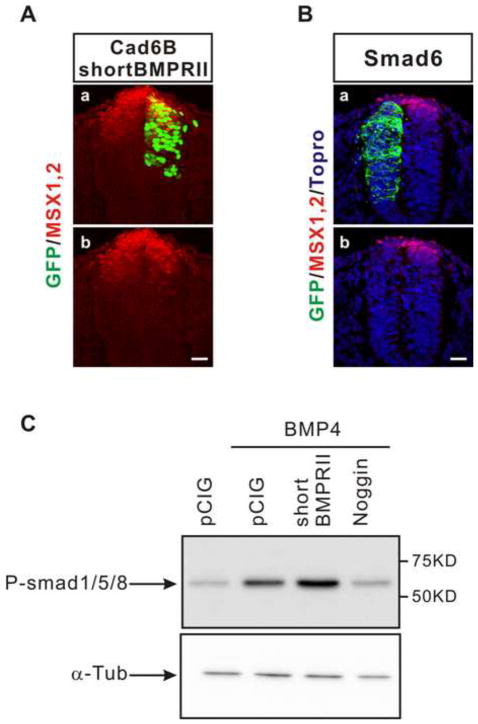

The BMPRII has uniquely long cytoplasmic tail following the kinase domain, which can interact with various cytoplasmic mediators in order to transduce non-canonical BMP signaling (Miyazono et al., 2010) A mutant of the BMP type II receptor lacking the unique cytoplasmic tail but retaining the kinase domain (short BMPRII) has been shown to be a specific inhibitor of non-canonical BMP signaling because the kinase domain is still able to phosphorylate BMP Type I receptor and mediate canonical signaling (Lee-Hoeflich et al., 2004; Nishihara et al., 2002). Therefore, we asked whether the short BMPRII affects de-epithelialization induced by cadherin-6B. ShortBMPRII significantly reduced cadherin-6B induced de-epithelialization (figure 3). Co-overexpression of shortBMPRII preserved the polarized localization of ZO-1 at the lumenal surface of neuroepithelial cells which express ectopic cadherin-6B (figure 3Ac,f and B). However, ectopically expressed wildtype BMP type II receptor (FL-BMPRII) did not affect de-epithelialization induced by cadherin-6B, presumably because it can still mediate non-canonical signaling and endogenous FL-BMPRII is enough for de-epithelialization induced by ectopic cadherin-6B (figure 3Ab,e and B). Although FL-BMPRII is able to mediate non-canonical signaling activated by cadherin-6B, FL-BMPRII alone did not induce de-epithelialization (figure. S2). The ectopic expression of short BMPRII did not decrease the endogenous expression of MSX1/2 in the dorsal neural tube (figure 4A), nor inhibit phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8 induced by ectopic BMP4 in the neural tube (figure. 4C). These results confirm that shortBMPRII does not interfere with canonical BMP signaling. Therefore, non-canonical BMP signaling as well as the long BMPRII cytoplasmic tail are involved in de-epithelialization induced by cadherin-6B.

Figure 3. The cytoplasmic tail of the BMP Type II receptor is required for cadherin-6B induced de-epithelialization.

(A) A mutant BMP Type II receptor lacking the cytoplasmic domain C-terminal to the kinase domain (shortBMPII) inhibits de-epithelialization induced by cadherin-6B. Ectopic cadherin-6B (Cad6B, red) disrupts of the polarized distribution of ZO-1 (blue) on the luminal surface of the neural tube and induces the accumulation of GFP positive cells inside of the lumen of the neural tube (a,d). Co-overexpression of shortBMPII inhibited de-epithelialization induced by cadherin-6B (c,f). Wild-type BMP Type II receptor (FL-BMPRII) did not affect de-epithelialization (b,e). IRES-GFP (green) marks the transfected cells. The percentage of examined sections per embryo exhibiting de-epithelialization (see methods) is shown as the mean ± s.d. in (B). 9 ~ 28 sections per embryo were used for the analysis (Cad6B; 93.1 ± 9.96 %, n= 8 embryos, Cad6B/FL-BMPRII; 91.2 ± 8.19 %, n= 9 embryos, Cad6B/shortBMPRII; 48.6 ± 35.09 %, n= 16 embryos). The same results are presented in two ways, single bar graph and points graph. *; P<0.0013, Scale bar: 25μm.

Figure 4. Short BMP Type II receptor does not inhibit canonical BMP signaling.

(A) Short BMP Type II receptor (shortBMPRII, n=4 embryos) does not affect endogenous expression of MSX1/2 (red) in the dorsal neural tube. Immuohistochemistry of MSX1/2 was performed with sections co-overexpressing cadherin-6B/shortBMPRII. (B) Smad6, inhibitory Smad, downregulates the endogenous expression of MSX1/2 (n=3 embryos). The transfected cells are marked by IRES-GFP (green) of the electroporated constructs. Nuclei were stained blue by To-Pro-3 (Topro, blue in B). Scale bar: 25μm. (C) ShortBMPRII does not block phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8 in response to BMP4. Western blot of phosphorylated Smad1/5/8 (P-smad1/5/8) was performed with embryos electroporated with control vector (pCIG), BMP4, BMP4/shortBMPRII, or BMP4/Noggin. Alpha-tubulin (α-Tub) is an internal control for Western blot of P-Smads. Co-overexpression of Noggin with BMP4 totally blocked phosphorylation of Smads induced by BMP4,but co-overexpression of shortBMPRII did not.

De-epithelialization induced by cadherin-6B or BMP is mediated by the LIM kinase/Cofilin pathway

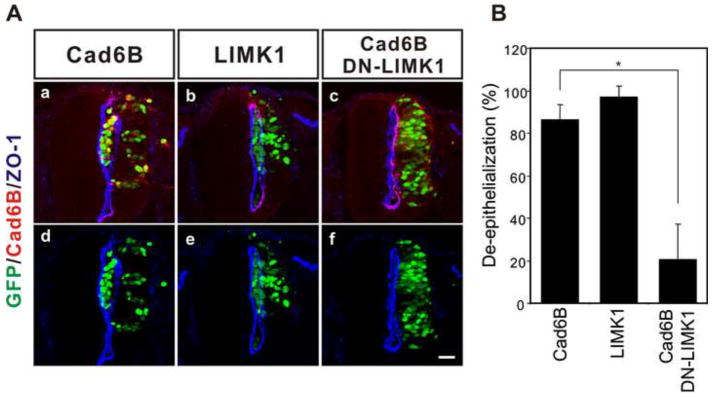

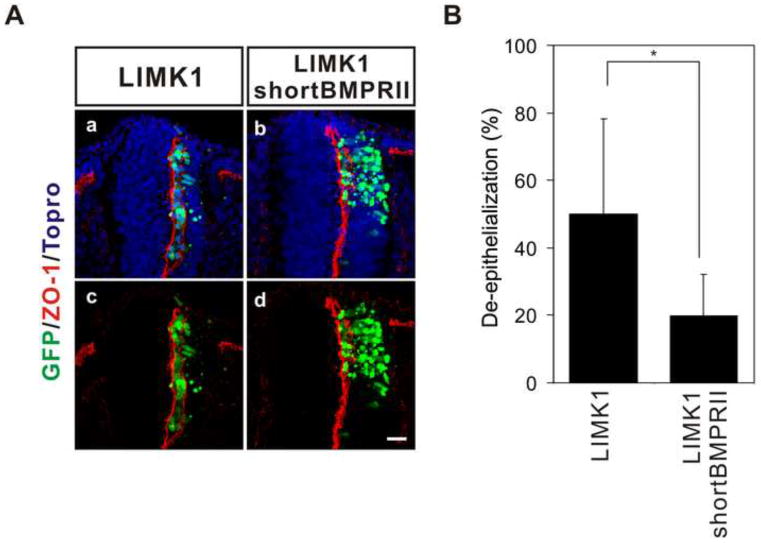

Non-canonical BMP signaling has been found to be transduced through several different mediators including LIM kinase 1 (LIMK1), Trb3 and Src, dependent on cellular context (Chan et al., 2007; Foletta et al., 2003; Hassel et al., 2004; Lee-Hoeflich et al., 2004; Miyazono et al., 2010; Wong et al., 2005). LIMK1 is expressed in most tissues of the developing embryo including the neural tube (Foletta et al., 2004). The activity of LIMK1 bound to cytoplasmic tail of BMP Type II receptor is regulated non-canonically by BMP (Foletta et al., 2003; Lee-Hoeflich et al., 2004) and the primary role of LIMK1 is to phosphorylate cofilin in order to regulate actin dynamics (Arber et al., 1998; Yang et al., 1998) as a mechanism to change cell morphology and/or migration. Therefore, we examined whether LIMK mediates cadherin-6B induced de-epithelialization in the neural tube. Ectopic expression of LIMK1 induced de-epithelialization of the neural epithelial cells of the neural tube (figure 5). The polarity of ZO-1 was disrupted at the luminal surface of the neural tube and GFP expressing cells (LIMK1-IRES-GFP) accumulated in the lumen (figure 5Ab,e). These effects were very similar to those induced by cadherin-6B (figure 1Ba–d and 3Aa,d) or BMP (figure 7Aa,e). Furthermore, dominant negative LIMK1 (DN-LIMK1), which is an inactive kinase form of LIMK1 and also behaves as a dominant negative, inhibited de-epithelialization induced by cadherin-6B (figure 5Ac,f and B). Therefore, LIMK1 appears to mediate cadherin-6B induced de-epithelialization in the neural tube. We also tried to determine whether de-epithelialization by LIMK1 occurred in functional association with the BMPRII. ShortBMPRII, the specific blocker of non-canonical BMP signaling, partially inhibited de-epithelialization induced by LIMK1 (figure 6). This suggests that LIMK1 may normally be regulated through binding to the tail of BMPRII, but still has some de-epithelialization activity on it own when expressed at high levels due to unregulated activity.

Figure 5. LIMK1 acts downstream of cadherin-6B to induce de-epithelialization.

(A) Ectopic LIMK1 expression induces de-epithelialization and dominant negative LIMK1 (DN-LIMK1) inhibits de-epithelialization induced by cadherin-6B. The transfected cells are marked by IRES-GFP (green) of the cadherin-6B (Cad6B) or LIMK1 expression constructs. Cadherin-6B expression is shown with immunostaining in red and the polarized distribution of ZO-1 (blue) delineates the luminal surface of the neural tube. The percentage of examined sections per embryo exhibiting de-epithelialization (see methods) is shown as the mean ± s.d. in (B). 13 ~ 21 sections per embryo were used for the analysis (Cad6B; 86.2 ± 7.05 %, n= 6 embryos, LIMK1; 96.9 ± 5.34 %, n= 7 embryos, Cad6B/DN-LIMK1; 20.4 ± 17.05 %, n= 5 embryos). *; P<0.001, Scale bar: 25μm.

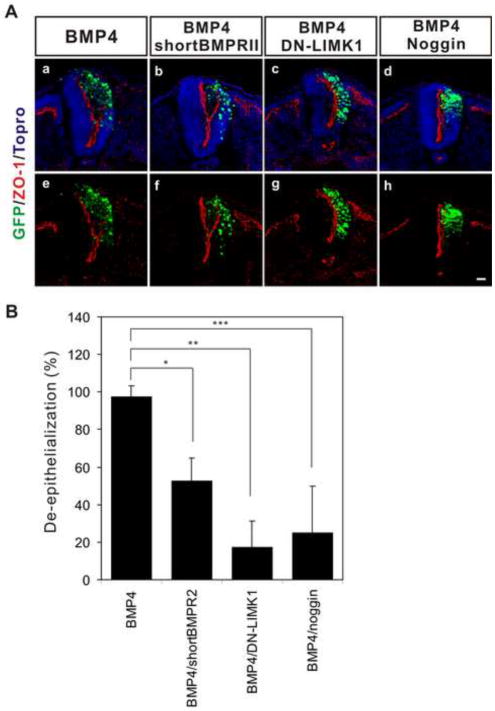

Figure 7. LIMK mediated non-canonical signaling through BMP Type II receptor is required for de-epithelialization induced by BMP4.

(A) BMP4 induced de-epithelialization is inhibited by co-overexpression of shortBMPRII, DN-LIMK1, or Noggin. The distribution of ZO-1 (red) represents the polarized apical surface of the neural tube. The percentage of examined sections per embryo exhibiting de-epithelialization (see methods) is shown as the mean ± s.d. in (B). 7 ~ 27 sections per embryo were used for the analysis (BMP4; 97.3 ± 5.96%, n= 5 embryos, BMP4/shortBMPRII; 52.4 ± 12.39%, n= 4 embryos, BMP4/DN-LIMK1; 17.1 ± 14.21%, n= 6 embryos; BMP4/Noggin; 25.0 ± 25.00%, n=3 embryos). IRES-GFP (green) marks the transfected cells. Nuclei were stained blue by To-Pro-3 (Topro, Aa,b,c,d). *; P<0.0002, **; P<0.0001, ***; P<0.0007, Scale bar: 25μm.

Figure 6. Non-canonical BMPRII signaling is required for de-epithelialization induced by LIMK1.

(A) Uncoupling LIMK1 from BMPRII using tailless shortBMPRII reduces LIMK1 induced de-epithelialization. The polarized distribution of ZO-1 (red) represents the apical surface of the neural epithelial cells. The percentage of examined sections per embryo exhibiting de-epithelialization (see methods) is shown as the mean ± s.d. in (B). 13 ~ 19 sections per embryo were used for the analysis (LIMK1; n= 7 embryos, LIMK1/shortBMPRII; n= 7 embryos). IRES-GFP (green) marks the transfected cells. Nuclei were stained blue by To-Pro-3 (Topro, Aa,b). *; P<0.032, Scale bar: 25μm.

De-epithelialization is induced by BMP as well as cadherin-6B in the neural tube (figure 7Aa,e). Therefore, we also examined whether the de-epithelialization induced by BMP is mediated by LIMK1. As expected, Noggin, an extracellular BMP antagonist, inhibited de-epithelialization induced by BMP4 (figure 7Ad,h and B). Importantly, both the shortBMPRII and DN-LIMK1 inhibited de-epithelialization induced by BMP4 (figure 7Ab,f,c,g and B). Therefore, it is likely that the effect of BMP on de-epithelialization of the neural tube is mediated by a LIMK1-dependent non-canonical BMP signaling pathway.

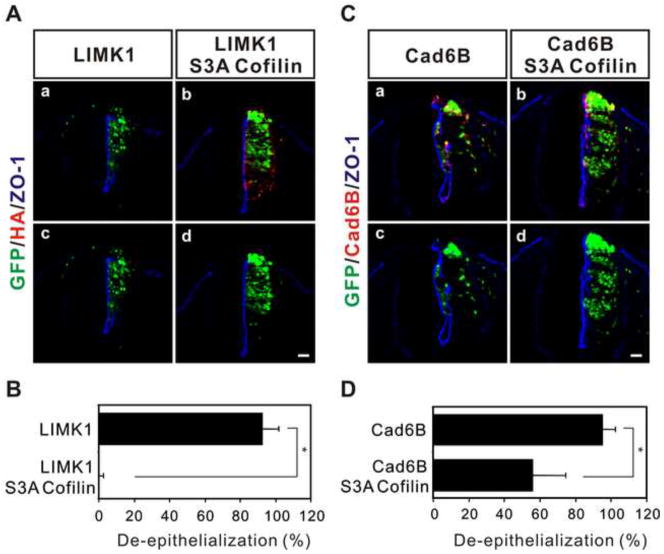

Cofilin and actin-depolymerizing factor (hereafter, together called cofilin) mediate LIMK signaling and play fundamental roles in actin dynamics (Arber et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2007; Yang et al., 1998). The actin filament severing activity of cofilin is reversibly regulated through phosphorylation and dephosphorylation on Ser3. Phosphorylation on Ser3 mediated by the LIMK family, including LIMK1/2, inhibits cofilin and de-phosphorylation of cofilin by the Slingshot family of phosphatases reactivates cofilin (Wang et al., 2007). Therefore, we examined whether cofilin is involved in de-epithelialization induced by cadherin-6B or LIMK1. S3A cofilin1, a phosphorylation-defective mutant of cofilin1 was co-overexpressed with either cadherin-6B or LIMK1. Co-overexpression of cadherin-6B and S3A cofilin1 was checked with the co-immunohistochemistry of cadherin-6B and HA (figure S3). S3A cofilin1 completely inhibited de-epithelialization induced by LIMK1 (figure 8Ab,d and B). De-epithelialization induced by cadherin-6B was also significantly inhibited by S3A cofilin1 (figure 8Cb,d and D). Therefore, cofilin appears to act downstream of LIMK in the induction of de-epithelialization by cadherin-6B and LIMK, and phosphorylation of cofilin is required for the de-epithelialization.

Figure 8. Cofilin mediates de-epithelialization induced by LIMK1 or cadherin-6B.

(A) De-epithelialization induced by LIMK1 is inhibited by S3A mutated cofilin (S3A-Cofilin). Ectopic expression of S3A cofilin is confirmed by HA staining (red). The percentage of examined sections per embryo exhibiting de-epithelialization (see methods) is shown as the mean ± s.d. in (B). 13 ~ 24 sections per embryo were used for the analysis (LIMK1; 92.5 ± 9.57%, n= 4 embryos, LIMK1/S3A-Cofilin; 0.7 ± 1.89%, n= 7 embryos). (C) De-epithelialization induced by cadherin-6B (Cad6B, red) is partially inhibited by S3A cofilin. The percentage of examined sections per embryo exhibiting de-epithelialization (see methods) is shown as the mean ± s.d. in (D). 8 ~ 24 sections per embryo were used for the analysis (cad6B; 95.2 ± 7.08%, n= 4 embryos, cad6B/S3A-Cofilin; 56.1 ± 18.27%, n= 6 embryos). The epithelial polarity of the neural tube is shown by the polarized distribution of ZO-1 (blue). The transfected cells are marked by IRES-GFP (green) of the electroporated constructs. *; P<0.004, Scale bar: 25μm.

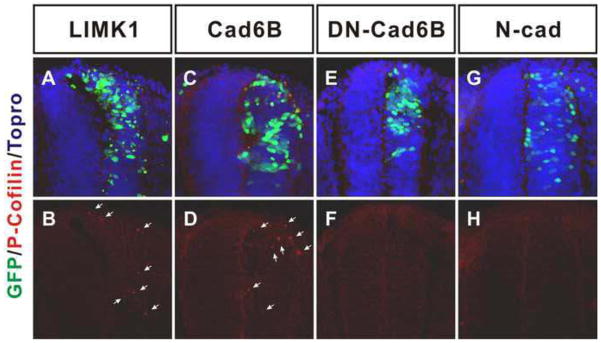

We then examined whether cadherin-6B can stimulate the phosphorylation of cofilin in the neural tube. We were not able to observe any increase in the levels of phospho-cofilin biochemically using immunoblotting of lysates of dissected embryonic tissue from embryos electroporated with cadherin-6B constructs (not shown). However, we believe that it is very difficult, if not impossible, to detect increased phosphorylation over the background of endogenous phosphorylated cofilin, because only a small portion of each neural tube is transfected by electroporation, and it is difficult to dissect neural tubes away from other tissues, which also may have endogenous phosphorylated cofilin. Therefore, we used immunohistochemical staining of phospho-cofilin. Ectopic expression of LIMK1, which is known to directly phosphorylate cofilin, stimulated immunostaining of phosphorylated Ser3 cofilin in transfected (GFP expressing) portions of the neural tube (figure 9A,B, 6 out of 6 embryos). The phosphorylated cofilin immunostaining was observed as pattern of spots or aggregates, similar to previous findings (Bravo-Cordero et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011), This indistinct pattern is presumably due to the fact that phosphorylated cofilin is the free non-actin associated form and cytosolic proteins are difficult to fix, especially in tissue prepared for cryosectioning. Importantly, ectopic cadherin-6B also increased immunostaining of phosphorylated cofilin in transfected (GFP expressing) portions of the neural tube (figure 9C,D) with a clear and consistent increase in the appearance of positive spots or aggregates over background samples (in both control embryos or unelectroporated neural tube halves) in 6 out of 6 embryos. In contrast to LIMK1 and cadherin-6B, N-cadherin and dominant negative cadherin-6B (DN-cad6B, glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol (GPI)-cadherin-6B), which don’t induce de-epithelialization (Park and Gumbiner, 2010), did not increase immunostaining of phosphorylated cofilin (figure 9E–H). Therefore, these results suggest that cadherin-6B specifically stimulates the LIMK/cofilin pathway to induce de-epithelialization of the neural tube.

Figure 9. Cadherin-6B stimulates phosphorylation of Cofilin.

Phosphorylation of cofilin was analyzed with immunohistochemistry (red). Ectopic expression of LIMK1 (A,B, 6 out of 6 embyos) and cadherin 6B (C,D, 5 out of 5 embryos) increases phosphorylation of cofilin at ser 3. Arrows indicate positive staining of phosphorylated cofilin. However, neither ectopic expression of dominant negative cadherin-6B (DN-Cad6B, E,F, 3 out of 3 embryos) nor N-cadherin (N-cad, G,H, 5 out of 5 embryos,) show phosphorylated cofilin positive staining. IRES-GFP (green) marks the transfected cells. Nuclei were stained blue by To-Pro-3 (Topro, blue in Ba,b). Scale bar: 25μm.

Cadherin-6B-induced LIMK1-dependent non-canonical BMP pathway stimulates the overall EMT of the neural crest

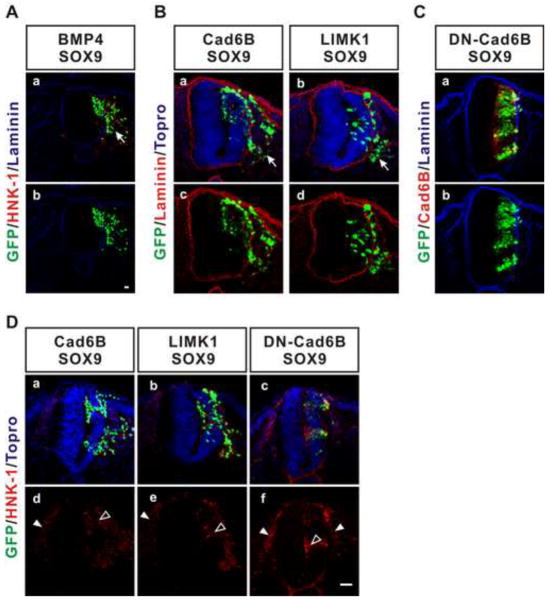

De-epithelialization provides a very robust assay to measure the activities of molecules that contribute to the first step of the EMT, but it is important to ask whether this cadherin-6B stimulated pathway actually promotes the overall EMT. We previously found that the EMT of the endogenous neural crest depended in part on cadherin-6B induced de-epithelialization (Park and Gumbiner, 2010). However, neither cadherin-6B nor BMP expression can induce full ectopic delamination of cells from the neural tube, because other factors are required in addition to de-epithelialization (Park and Gumbiner, 2010). Interestingly, slug is a transcription factor thought to be involved in the EMT in a variety of tissues, but it can only induce ectopic delamination in the neural tube when it is co-expressed with SOX9, another transcription factor that provides competence for the EMT (Cheung et al., 2005; Park and Gumbiner, 2010). Similarly, we observe that co-overexpression of cadherin-6B and SOX9 induced robust ectopic delamination in the neural tube (figure 10Ba,c). Laminin delineates the basement membrane of the neural tube, and cells expressing cadherin-6B/SOX9 cross the basement membrane to exit the neural tube (figure 10Ba,b). Ectopic BMP4 by itself only induces de-epithelialization in the neural tube (figure 7Aa,e), but BMP4 is also able to induce ectopic delamination when co-expressed with SOX9 (figure 10Aa,b). In contrast, dominant negative cadherin 6B (DN-cadherin-6B), which does not induce de-epithelialization (Park and Gumbiner, 2010), does not induce ectopic delamination when co-overexpressed with SOX9 (figure 10Ca,b). These findings support our previous conclusion that de-epithelialization is the first step of the overall EMT of the neural crest (Park and Gumbiner, 2010). Importantly, LIMK1 also induced robust ectopic delamination when co-overexpressed with SOX9 (figure 10Bb,d). Cells de-epithelialized with ectopic Cadherin-6B (Park and Gumbiner, 2010) or LIMK1 without SOX9 (figure S4) do not express HNK-1 or cadherin 7 which are markers of the migrating neural crest cells. However, co-overexpression of SOX9 along with cadherin-6B or LIMK1 induces HNK-1 in GFP positive neuroepithelial cells as well as in ectopically delaminating GFP positive cells (figure 10Da,b,d,e), similarly to expression of SOX9 alone (Cheung et al, 2003). Therefore, de-epithelialization induced by LIMK1-dependent non-canonical BMP signaling appears to contribute to the overall EMT similar to de-epithelialization induced by cadherin-6B or BMP in the neural tube. Thus, in the appropriate context, the cadherin-6B stimulated noncanonical BMPR-LIMK pathway promotes the full EMT and delamination of migratory neural crest.

Figure 10. De-epithelialization induced by cadherin-6B or LIMK1 contributes to ectopic delamination.

(A–C) Ectopic expression of SOX9 along with BMP4 (A, 3 out of 3 embryos), cadherin-6B (B, Cad6B, 9 out of 9 embryos), or LIMK1 (B, 7 out of 7 embryos) induces ectopic delamination. As a control, co-expression of dominant negative cadherin-6B (DN-Cad6B) and SOX9 does not induce ectopic delamination (C, 3 out of 3 embryos). The basement membrane is delineated by laminin staining (red in B or blue in A and C). Arrows indicate the cells which have undergone ectopic delamination (Aa, Ba,b). (D) HNK-1, a marker of the migrating neural crest cells, is expressed in GFP positive neuroepithelial cells after ectopic expression of SOX9 along with cadherin-6B (a,d, 7 out of 7 embryos), LIMK1 (b,e, 9 out of 9 embryos), or DN-Cad6B, (c,f, 3 out of 3 embryos), regardless of ectopic delamination, similarly to expression of SOX9 alone (Cheung et al, 2003). Closed arrow heads indicate endogenous migrating neural crest cells expressing HNK-1. Open arrow heads indicate GFP positive neuroepithelial cells expressing HNK-1. IRES-GFP (green) marks the transfected cells. Nuclei were stained blue by To-Pro-3 (Topro, blue in Ba,b). Scale bar: 25μm.

DISCUSSION

We previously provided evidence that cadherin-6B expression in the trunk premigratory neural crest promotes the initial step in the EMT neural crest by triggering a de-epithelialization of the neuroepithelial cells in the dorsal neural tube (Park and Gumbiner, 2010); and we discussed the differences from the alternate reported role of cadherin-6B in cranial neural crest (Coles et al., 2007; Taneyhill et al., 2007). Importantly, we found that this de-epithelialization step was not directly due to the adhesive role of cadherin-6B, but rather due to its local stimulation of BMP receptor signaling, independent of the ligand, BMP. In this study, we confirm and extend these findings on cadherin-6B induced BMP receptor signaling in de-epithelialization. We found that it does so via a known BMP Type II receptor-mediated non-canonical pathway. This non-canonical BMPRII pathway is stimulated by both cadherin-6B and BMP and involves LIMK phosphorylation of the actin severing protein cofilin, similar to a pathway that has previously been found to mediate the effects of BMP on the actin cytoskeleton (Foletta et al., 2003; Lee-Hoeflich et al., 2004). Importantly, we also find that LIMK signaling, as well as cadherin-6B and BMP, can promote neural crest cell delamination from the neural tube when co-expressed with SOX9, a transcription factor that enables neural crest delamination in other contexts (Cheung et al., 2005; Park and Gumbiner, 2010), indicating that this non-canonical pathway is involved in the overall EMT.

In our previous study, we initially detected cadherin-6B induced BMP signaling via the BRE-lacZ reporter assay, and then demonstrated the requirement for BMP signaling in de-epithelialization using inhibitors of BMPR signaling (Park and Gumbiner, 2010). However, we now show that de-epithelialization does not appear to involve the induction of Smad-dependent BMPR target genes, since factors that induce de-epithelialization do not turn on the known BMP canonical target genes, MSX1/2, nor does activation of Smad-dependent target genes by constitutively active Type I receptor cause de-epithelialization. Also cadherin-6B or LIMK1 does not induce Smads phsophorylation, nor does shortBMPRII, which inhibits de-epithelialization, block phosphorylation of Smads in response to BMP4. We previously observed that Smad6 inhibits de-epithelializtion induced by cadherin-6B (Park and Gumbiner, 2010). Smad6 or Smad7 are known to interact with Smurf2 to mediate downregulation of BMP/TGF-β receptors complexes (Kavsak et al., 2000), and this downregulation of BMPRs complex might inhibit non-canonical BMP signaling as well as canonical. We do not know why cadherin-6B induces the BRE-lacZ reporter; it is either due to an indirect effect, a nonspecific effect, or else the non-canonical BMPR pathway may be able to indirectly regulate the expression of some genes in addition to regulation of the actin cytoskeleton via LIMK-cofilin.

Several non-canonical, Smad-independent BMP and TGFβ signaling pathways have been described that could potentially regulate the cytoskeleton and/or de-epithelialization. One that seemed particularly relevant to the neural crest EMT is the finding that TGFβ can induce the EMT in cultured tumor epithelial cells via a direct cytoplasmic pathway involving par6 (Ozdamar et al., 2005). The phosphorylation of Par6 by the TGFβ Type II receptor is necessary for the localized ubiquitinylation of RhoA to induce TGFβ dependent dissolution of tight junctions in the EMT. However, a dominant negative inhibitor of this pathway had no effect on cadherin-6B induced de-epithelialization. Moreover, we found a requirement for the unique cytoplasmic domain of the BMPRII, which is not found in TGFβ receptors. Because non-canonical BMPRII signaling through LIMK1 has been found to have a role in regulation of the cytoskeleton (Foletta et al., 2003; Lee-Hoeflich et al., 2004), this pathway was a good candidate for regulation of de-epithelialization, which must involve re-organization of the cytoskeleton in some way. Indeed, we found strong evidence that cadherin-6B or BMP induced de-epithelialization depends in part on LIMK and its substrate cofilin. Other molecules have been found to interact with the long cytoplasmic domain of BMPRII, including Trb3 (Chan et al., 2007) and Src (Wong et al., 2005), and have also been proposed to mediate non-canonical BMPRII signaling. Our data strongly implicated the better-known LIMK-cofilin pathway, but we cannot exclude that these other factors might also play a partial role, since DN-LIMK and mutant cofilin did not completely inhibit de-epithelialization by cadherin-6B.

Other factors, that are induced by BMP signaling in the neural tube and play a role in EMT of the neural crest, might also play a role in de-epithelialization mediated by non-canonical BMPRII signaling. RhoB is one such factors (Cheung et al., 2005; Liu and Jessell, 1998). However, we observed that dominant negative RhoB did not inhibit de-epithelialization induced by cadherin-6B (data not shown). The mechanism of de-epithelialization induced by cadherin-6B/LIMK might function in parallel with a RhoB dependent mechanism of EMT of the neural crest in chick.

It is not yet clear how cadherin-6B activates BMPRII-dependent LIMK1 signaling. There have been differing reports on how LIMK1 might be regulated in non-canonical BMP signaling via BMPRII (Foletta et al., 2003; Lee-Hoeflich et al., 2004). One study has shown that the catalytic activity of LIMK1 is inhibited by its binding to BMPRII (Foletta et al., 2003). PAK4, one of the LIMK1 activators cannot activate LIMK1 because BMPRII binds LIMK1. However, BMP treatment induces dissociation of LIMK1 from the LIMK1/BMPRII complex and the free LIMK1 is activated by PAK. In contrast, another study has reported that binding of LIMK1 to the c-terminal tail of the BMPRII activates LIMK1, because the binding blocks LIMK1 intramolecular interaction between LIM domains and the kinase domain which negatively regulates LIMK1 (Lee-Hoeflich et al., 2004). After BMP treatment, the bound LIMK1 is further activated by Cdc42 which is activated by BMP. In either case, the interaction between LIMK1 and BMPRII is required for the regulation of LIMK1 activity in non-canonical BMP signaling. It is possible therefore, that cadherin-6B positively regulates the functional or physical interaction between LIMK1 and BMPRII independent of BMP and facilitates formation of the LIMK1/BMPRII activation complex. Importantly, ectopic BMPRII did not induce de-epithelialization without cadherin-6B. It is likely that BMPRII-LIMK1 signaling is dependent on cadherin-6B. It is also possible that the cytoplasmic tail of cadherin-6B plays a role in the activation of BMPRII/LIMK1 signaling, because dominant negative cadherin-6B lacking cytoplasmic tail does not induce de-epithelialization (Park and Gumbiner, 2010). Of course, any mechanism must take into account that it is a cadherin specific function, as N-cadherin does not activate this pathway.

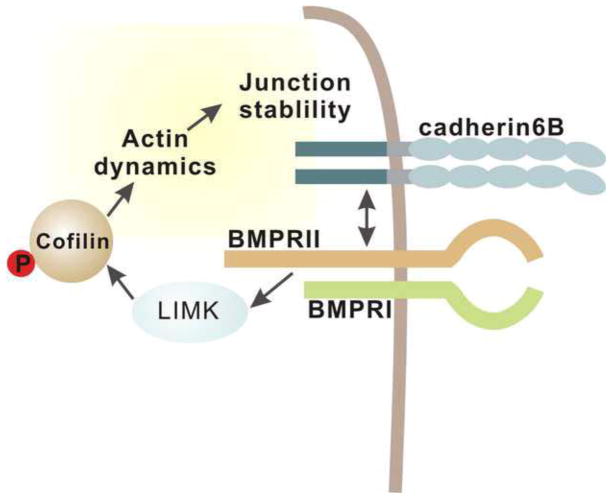

Through its regulation of actin filament severing, cofilin plays many different important roles in morphogenesis and cell migration, including many events in the neural tube and the neural crest (Gurniak et al., 2005). Active cofilin severs actin filaments resulting in forming free barbed ends in order to induce actin polymerization at the new free barbed ends. Since phosphorylation of cofilin by LIMK1 inhibits its actin severing function, the question arises as to how cofilin inactivation could be required for cadherin-6B induced de-epithelialization in the neural tube. One possibility is that local changes in actin dynamics at the cell junctions could have roles in junction stability and thereby epithelial polarity (figure 11). For example, it has been reported that Par3, a polarity protein inhibits LIMK2 and promotes tight junction assembly, and that S3A phosphorylation deficient mutant of cofilin can restore tight junctions in Par3 knockdown cells (Chen and Macara, 2006). It is also known that cofilin dynamics is linked to tight junction stability (Nagumo et al., 2008). More recently, it was reported that knockdown of cofilin disturbs E-cadherin dependent adhesion in the zebrafish embryo (Lin et al., 2010). In more general terms, the spatial and temporal regulation of cofilin activity is essential for the polarity and directional migration of cells (Mouneimne et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2011). De-epithelialization is a complex process involving many aspects of cell organization and behavior, which can be mediated by actin dynamics in numerous ways. Phosphorylation of cofilin by LIMK1 could interfere with the maintenance of epithelial polarity and thereby cause de-epithelialization as the first step in the EMT.

Figure 11. A model for how interactions between cadherin-6B and activation of BMPRII/LIMK signaling regulate junction stability through cofilin regulation of actin dynamics.

Cadherin-6B activates non-canonical BMP signaling mediated by BMPRII. The activated non-canonical BMP signaling regulates cofilin dynamics through LIMK. Actin dynamics regulated by cofilin might play a role in regulation junction stability. In the neural crest, cadherin-6B plays a role not only in the intercellular adhesions, but also in the local regulation of the intracellular signaling in order to integrate outside/inside signals between neighbors.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall our findings provide an explanation for how a specific cadherin, which is normally expected to support the formation of polarized epithelia, could specifically induce de-epithelialization. Cadherin-6B does so by inducing a specific cytoplasmic signaling pathway, the noncanonical BMPR-LIMK pathway, that regulates the organization of the actin cytoskeleton and presumably disrupts cell junctional polarity. Furthermore, in the proper context, stimulation of the noncanonical BMPR-LIMK pathway by either cadherin-6B or BMP can mediate the full neural crest EMT.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Cadherin-6B promotes the epithelial mesenchymal transition of neural crest cells

Cadherin-6B-induces de-epithelialization via noncanonical BMP receptor signaling

De-epithelialization is mediated by BMP receptor activation of LIM kinase

LIM kinase phosphorylates the actin regulatory protein cofilin

With Sox9 this pathway leads to delamination of neural crest from the neural tube

Acknowledgments

We thank Xiaowei Lu and Jing Yu for helpful discussions and suggestions. This work was supported by NIH Grant R37GM37432-24S1 to Barry Gumbiner.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams CL, Nelson WJ, Smith SJ. Quantitative analysis of cadherin-catenin-actin reorganization during development of cell-cell adhesion. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1899–1911. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arber S, Barbayannis FA, Hanser H, Schneider C, Stanyon CA, Bernard O, Caroni P. Regulation of actin dynamics through phosphorylation of cofilin by LIM-kinase. Nature. 1998;393:805–809. doi: 10.1038/31729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo-Cordero JJ, Oser M, Chen X, Eddy R, Hodgson L, Condeelis J. A novel spatiotemporal RhoC activation pathway locally regulates cofilin activity at invadopodia. Curr Biol. 2011;21:635–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan MC, Nguyen PH, Davis BN, Ohoka N, Hayashi H, Du K, Lagna G, Hata A. A novel regulatory mechanism of the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway involving the carboxyl-terminal tail domain of BMP type II receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5776–5789. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00218-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Macara IG. Par-3 mediates the inhibition of LIM kinase 2 to regulate cofilin phosphorylation and tight junction assembly. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:671–678. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung M, Briscoe J. Neural crest development is regulated by the transcription factor Sox9. Development. 2003;130:5681–5693. doi: 10.1242/dev.00808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung M, Chaboissier MC, Mynett A, Hirst E, Schedl A, Briscoe J. The transcriptional control of trunk neural crest induction, survival, and delamination. Dev Cell. 2005;8:179–192. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles EG, Taneyhill LA, Bronner-Fraser M. A critical role for Cadherin6B in regulating avian neural crest emigration. Dev Biol. 2007;312:533–544. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature. 2003;425:577–584. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foletta VC, Lim MA, Soosairajah J, Kelly AP, Stanley EG, Shannon M, He W, Das S, Massague J, Bernard O. Direct signaling by the BMP type II receptor via the cytoskeletal regulator LIMK1. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:1089–1098. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foletta VC, Moussi N, Sarmiere PD, Bamburg JR, Bernard O. LIM kinase 1, a key regulator of actin dynamics, is widely expressed in embryonic and adult tissues. Exp Cell Res. 2004;294:392–405. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumbiner BM. Regulation of cadherin-mediated adhesion in morphogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:622–634. doi: 10.1038/nrm1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurniak CB, Perlas E, Witke W. The actin depolymerizing factor n-cofilin is essential for neural tube morphogenesis and neural crest cell migration. Dev Biol. 2005;278:231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassel S, Eichner A, Yakymovych M, Hellman U, Knaus P, Souchelnytskyi S. Proteins associated with type II bone morphogenetic protein receptor (BMPR-II) and identified by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 2004;4:1346–1358. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavsak P, Rasmussen RK, Causing CG, Bonni S, Zhu H, Thomsen GH, Wrana JL. Smad7 binds to Smurf2 to form an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets the TGF beta receptor for degradation. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1365–1375. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski AV, Maiden SL, Pokutta S, Choi HJ, Benjamin JM, Lynch AM, Nelson WJ, Weis WI, Hardin J. In vitro and in vivo reconstitution of the cadherin-catenin-actin complex from Caenorhabditis elegans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:14591–14596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007349107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee-Hoeflich ST, Causing CG, Podkowa M, Zhao X, Wrana JL, Attisano L. Activation of LIMK1 by binding to the BMP receptor, BMPRII, regulates BMP-dependent dendritogenesis. Embo J. 2004;23:4792–4801. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CW, Yen ST, Chang HT, Chen SJ, Lai SL, Liu YC, Chan TH, Liao WL, Lee SJ. Loss of Cofilin 1 Disturbs Actin Dynamics, Adhesion between Enveloping and Deep Cell Layers and Cell Movements during Gastrulation in Zebrafish. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JP, Jessell TM. A role for rhoB in the delamination of neural crest cells from the dorsal neural tube. Development. 1998;125:5055–5067. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.24.5055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J. TGFbeta in Cancer. Cell. 2008;134:215–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazono K, Kamiya Y, Morikawa M. Bone morphogenetic protein receptors and signal transduction. J Biochem. 2010;147:35–51. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvp148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouneimne G, DesMarais V, Sidani M, Scemes E, Wang W, Song X, Eddy R, Condeelis J. Spatial and temporal control of cofilin activity is required for directional sensing during chemotaxis. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2193–2205. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagumo Y, Han J, Bellila A, Isoda H, Tanaka T. Cofilin mediates tight-junction opening by redistributing actin and tight-junction proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:921–925. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishihara A, Watabe T, Imamura T, Miyazono K. Functional heterogeneity of bone morphogenetic protein receptor-II mutants found in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:3055–3063. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-02-0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozdamar B, Bose R, Barrios-Rodiles M, Wang HR, Zhang Y, Wrana JL. Regulation of the polarity protein Par6 by TGFbeta receptors controls epithelial cell plasticity. Science. 2005;307:1603–1609. doi: 10.1126/science.1105718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KS, Gumbiner BM. Cadherin 6B induces BMP signaling and de-epithelialization during the epithelial mesenchymal transition of the neural crest. Development. 2010;137:2691–2701. doi: 10.1242/dev.050096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SD, Ciatto C, Chen CP, Bahna F, Rajebhosale M, Arkus N, Schieren I, Jessell TM, Honig B, Price SR, Shapiro L. Type II cadherin ectodomain structures: implications for classical cadherin specificity. Cell. 2006;124:1255–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Moreno M, Jamora C, Fuchs E. Sticky business: orchestrating cellular signals at adherens junctions. Cell. 2003;112:535–548. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podkowa M, Zhao X, Chow CW, Coffey ET, Davis RJ, Attisano L. Microtubule stabilization by bone morphogenetic protein receptor-mediated scaffolding of c-Jun N-terminal kinase promotes dendrite formation. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:2241–2250. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01166-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig BL, Imamura T, Okadome T, Cox GN, Yamashita H, ten Dijke P, Heldin CH, Miyazono K. Cloning and characterization of a human type II receptor for bone morphogenetic proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7632–7636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Massague J. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;113:685–700. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoval I, Ludwig A, Kalcheim C. Antagonistic roles of full-length N-cadherin and its soluble BMP cleavage product in neural crest delamination. Development. 2007;134:491–501. doi: 10.1242/dev.02742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneyhill LA, Coles EG, Bronner-Fraser M. Snail2 directly represses cadherin6B during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions of the neural crest. Development. 2007;134:1481–1490. doi: 10.1242/dev.02834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmer JR, Wang C, Niswander L. BMP signaling patterns the dorsal and intermediate neural tube via regulation of homeobox and helix-loop-helix transcription factors. Development. 2002;129:2459–2472. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.10.2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Eddy R, Condeelis J. The cofilin pathway in breast cancer invasion and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:429–440. doi: 10.1038/nrc2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong WK, Knowles JA, Morse JH. Bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II C-terminus interacts with c-Src: implication for a role in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;33:438–446. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0103OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Weinberg RA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition: at the crossroads of development and tumor metastasis. Dev Cell. 2008;14:818–829. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang N, Higuchi O, Ohashi K, Nagata K, Wada A, Kangawa K, Nishida E, Mizuno K. Cofilin phosphorylation by LIM-kinase 1 and its role in Rac-mediated actin reorganization. Nature. 1998;393:809–812. doi: 10.1038/31735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Luo J, Wan P, Wu J, Laski F, Chen J. Regulation of cofilin phosphorylation and asymmetry in collective cell migration during morphogenesis. Development. 2011;138:455–464. doi: 10.1242/dev.046870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.