Abstract

This study compared the neurology residency training experience for a single neurology resident at the University of Pennsylvania from the years 2002–2005. The prevalence of encounters seen during this residency was compared to the prevalence of neurological disorders typically observed by ambulatory neurologists in the United States (US). A total of 1,333 patients were evaluated during this residency. Ischemic stroke/ transient ischemic accident, epilepsy, metabolic encephalopathy, peripheral neuropathy, and multiple sclerosis were the most common neurological disorders observed. The four most common reasons for an outpatient visit to a neurologist (i.e. headache/migraine, epilepsy, cerebrovascular disease, and peripheral neuropathy) typically account for ~ 49–55% of all appointments, but only contributed to ~40% of patient encounters during this neurology residency. While these results reflect the encounters of a single neurology resident, both the total number and distribution of neurological diagnoses were similar to previous experiences over two decades ago at US academic medical centers despite significant changes in health care delivery and policy. This case report demonstrates that neurology residency programs continue to overemphasize acute management of inpatient neurological disorders compared to outpatient care of more prevalent neurological complaints. Additional measures could be instituted to ensure a broader range of experiences during residency (i.e. online resident log). These methods could allow residency coordinators to identify certain areas of deficiency in regards to exposure to patients for a resident and ensure greater competency during residency.

Keywords: Education, Residency

INTRODUCTION

Neurology training in the United States (US) continues to evolve in response to our greater understanding of neurological disorders and the discovery of new therapies. In the past few years significant changes have occurred in neurology residency training programs. Program directors are constantly trying to abide to resident review committee (RRC) regulations while ensuring adequate training of future neurologists [1].

One way to assess if these changes in policy have impacted neurology training is to access the total number and type of neurological diseases that have been observed during a residency experience. To date, a small series of case studies have investigated the personal experiences of some residents over various time periods in the US, Canada, and the United Kingdom (UK) [2, 8, 10]. D’Esposito noticed that his residency training overemphasized the management of acute inpatient neurologic disorders that are less prevalent in the US compared with outpatient care of more prevalent disorders commonly seen in a neurology practice. Moore and Cloak subsequently presented their neurological training experiences in the US and Canada as well as Maddison presented his training encounters in the UK. A decade later each of these residents observed a relative similarity in patient profiles to those previously seen by D’Esposito. For these case reports the neurologic disorders seen during training did not reflect the incidence and lifetime prevalence of these disorders seen by community neurologists [6, 7].

More recently the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has enacted a work hour requirement for all resident physicians within the US [15]. These rules limit duty hours to 80 per week; require residents to have at least 1 day in 7 to be free from all educational and clinical responsibilities; and ensure adequate time for rest and personal activities [5]. While much has been written concerning the effect of these regulation on residency training, to date no conclusive evidence has been shown that these changes have improved patient safety or the quality of experiences during residency [13]. In fact, many changes that have been instituted could have a deleterious impact on the total number and variety of neurological disorders encountered by residents [14]. In an attempt to compare results from previous case reports [2, 8, 10] to more recent experiences after enactment of ACGME duty hour regulations, the patient log of a single neurology resident was assessed during the years 2002–2005.

METHODS

Prospective data were collected concerning all new patients encountered by a single neurology resident from 2002–2005 at the University of Pennsylvania adult neurology residency program. Follow-up encounters (either inpatient or outpatient) were not included in the analysis. Clinical information was collected for each patient with principal diagnosis determined after completion of the neurological evaluation. If a patient was noted to have multiple diagnoses during a work-up, the primary reason for an encounter was chosen. For purposes of comparison to previous studies conducted in the US, all adult and pediatric patients seen were classified into one of a possible 20 broad diagnostic categories that encompass all neurologic disorders [2, 8, 10]. New patient encounters were also categorized by encounter type as either: inpatient admission, inpatient consultations, or outpatient evaluation. The proportions of disorders seen during this residency were compared to the most common reasons for an office visit to a community neurologist [6, 9].

RESULTS

Patients were evaluated at three university based hospitals. Adult patients were seen at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (26 months) and Pennsylvania Hospital (4 months) while pediatric patients were seen at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (3 months). Clinical exposure in adult neurology consisted of the following rotations: inpatient service (15 months), consultation service (4 months), and outpatient service (3 months of outpatient clinic only and 1 afternoon per week throughout residency). A rotation in psychiatry was not performed as this residency was completed prior to a change in residency requirements. Adult outpatient electives were each one month in duration and consisted of the following 7 rotations: electroencephalography, electromyography, neuro-opthomology, movement disorders, neuro-oncology, neuropathology, and neuroradiology. Patients who were evaluated during electrodiagnostic or neuroradiology elective rotations were not included in the analysis of new patient encounters in order to allow for comparison to previous experiences by neurologists in training.

A total of 1,333 new patients were evaluated during the 3-year period of the residency. These encounters consisted of a total of 1,002 inpatient encounters (364 (48%) as admissions to the neurology service and 638 (27%) as neurology consults) and 331 (25%) were outpatient neurology visits. A total of 638 patients were encountered during the first year of residency, 346 during the second year, and 331 during the third year. This distribution of patient encounters reflects the curriculum of the University of Pennsylvania residency program, with most inpatient rotations occurring during the first and second years of training, while more outpatient and elective rotations scheduled during the end of the second and third years.

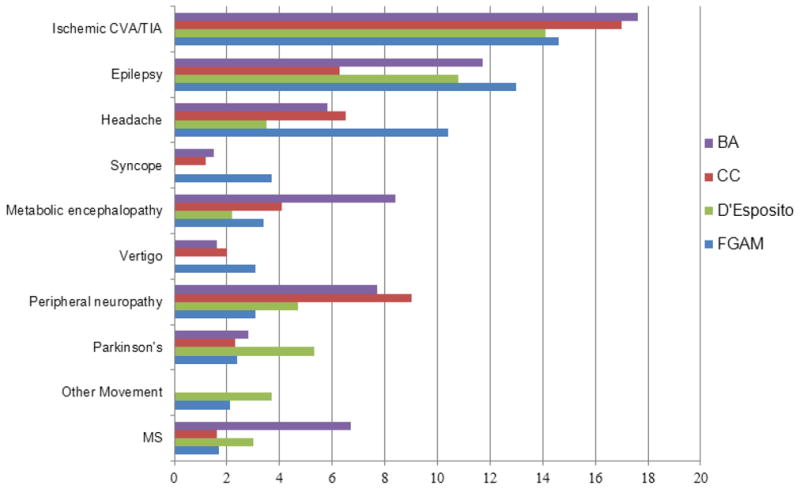

The ten most common primary diagnoses seen during this residency were tabulated and compared to previous studies in the US (Table 1). These ten common disorders accounted for 71% of all patients seen during this residency. In particular, the top two diagnoses seen during this residency (ischemic cerebrovascular disease and epilepsy) were similar to previous US studies [2, 10] (Figure 1). However, a higher percentage of patients with metabolic encephalopathy and multiple sclerosis were observed during this residency compared to previous neurology residency experiences.

Table 1.

Top 10 Most Common Neurological Diagnoses Encountered During Residency and Comparison to Previous Experiences in the United States.

| Resident CC 10 | Resident MD 2 | Resident BA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Variables | |||

| Institution Residency Performed | Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota | Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts | University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Residency Years | 1986–1989 | 1988–1991 | 2002–2005 |

| Total Number of Patients Seen | 1009 | 1332 | 1333 |

| Neurological Disorder: Total number (%) | |||

| Ischemic CVA/TIA | 172 (17%) | 188 (14%) | 243 (18%) |

| Epilepsy | 64 (6 %) | 144 (11%) | 162 (12%) |

| Metabolic encephalopathy | 41 (4%) | 29 (2%) | 116 (8%) |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 91 (9%) | 63 (5%) | 106 (8%) |

| Multiple sclerosis | 16 (2%) | 40 (3%) | 92 (7%) |

| Headache | 66 (7%) | 47 (4%) | 80 (6%) |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 28 (3%) | NA | 49 (4%) |

| Parkinson's disease | 26 (2%) | 70 (5%) | 38 (3%) |

| Unknown/ other neurological disorders | 35 (4%) | 21 (2%) | 37 (3%) |

| Central nervous system infection | 20 (2%) | NA | 33 (2%) |

NA= not available

Figure 1. The ten most common diagnostic categories encountered during this neurology residency compared to previous US experience.

All data are expressed as a percentage of the total new patients seen and are compared to existing literature (CC and FGAM from Moore and Chalk, 2005 and D’Esposito from D’Esposito, 1995).

Using these diagnostic categories, the prevalence of encounters seen during this residency was compared to the most common reasons for an office visit to a community neurologist [6, 7]. The four most common neurologic complaints (headache, epilepsy, neuropathy, and cerebrovascular disease) accounted for ~49–55% of the total neurologic burden in the US [6]. These same four diagnoses represented ~40% of all patient encounters during this neurology residency. More than 10% of all patients present to a community neurologist with neck/back pain, sleep disorders, or cognitive complaints [6]. However, during this residency these diagnoses accounted for less than 1% of all patients seen. In addition, several diagnoses were overrepresented. For example, uncommon disorders (primary brain neoplasms, metastases to the brain and spinal cord, cranial neuropathies, myasthenia gravis, and myopathies) account for < 1% of the total number of visits to an ambulatory neurologist setting but comprised > 6% of all new patients encountered during this residency.

DISCUSSION

While this case report reflects the experiences of a single neurology resident it still demonstrates that both the total number as well as the neurological diagnoses observed were similar to previous experiences at US academic medical centers despite changes in health care delivery and ACGME residency requirements. The observed lack of change over two decades may in fact reflect the stability in subsidization for residents. For more than fifty years, graduate medical education has been primarily funded through Medicare, Medicaid, the Department of Veterans Affairs, the Department of Defense, the Public Health Service, and disproportionate share payments to hospitals in underserved areas.

These observations continue to suggest that neurology residency programs in the US continue to overemphasize acute inpatient care of less prevalent neurological disorders compared to outpatient care of more prevalent diseases seen in the general population [12]. In particular, 75% of all new patient encounters were seen in the inpatient setting with similar results seen two decades ago (65–72%) [2, 10]. Since a large portion of residency is spent in the inpatient arena, current neurology residency experiences tend to focus on a limited number of neurological disorders. Several areas, such as training in neurorehabilitation, ethics, end-of-life/palliative care, office management, and medical-legal/malpractice evaluations were not available during this residency and should receive further emphasis [14]. Coverage of these topics in outpatient clinical rotations could help ensure that neurology is continued to be included as a primary care specialty. Greater exposure to ambulatory patients, including in community practice settings and in staff model health maintenance organizations should be considered. In some instances community physicians have be given the opportunity to supervise students and residents in university settings, but few programs send students or residents to community practices. Neurology departments have been slow to adopt community rotations due to lack of financing and difficulty ensuring an optimal educational experience [11].

A number of limitations exist for this case report. Although the recorded new patient encounters were obtained prospectively, the study itself was retrospective in nature. Differences could occur in how the primary diagnosis was determined in this study compared to previous work, although this is likely to be non-significant. Second, this study only reflects the more recent experience of a single resident in the US. Questions also remain as to how typical these experiences are compared to other US neurology residents since ACGME changes in policy. An attempt to compare neurology resident experiences across programs in the US using a residency log system met considerable resistance [4]. Compared to other specialties (i.e. obstetrics and surgery) [3], objective criteria for the certification of a qualified neurology resident based on individual clinical exposure (i.e., patient encounters) does not exist. Neurology residency program supervisors continue to face the dilemma of how to ensure that neurology residents adequately comply with RRC guidelines. An online resident log could allow residency coordinators to identify certain areas of deficiency in regards to exposure to certain neurological disorders and ensure competency. As part of this reaccreditation process for neurology residencies, the RRC could review these resident logs to determine whether a neurology programs provided sufficient breath of neurological experiences for their graduates. The exact number and exact type of patients that should be seen remains unresolved and should be determined by the ACGME and RRC. Information gleaned from a residency log at each institution could also highlight a program's strengths and enhance its’ attractiveness to applicants. Third, this study compares results to those previously obtained at major academic medical centers in the US. Significant differences may exist amongst other countries in terms of length, formal structure and organization [8]. In addition, an institutional bias may exist. Faculty expertise may differ at various institutions depending on if the department is more academic compared to community based. While the University of Pennsylvania is an international leader in a number of subspecialties an increase in the number of patients for many disorders (i.e. dementia) was not observed. These results may reflect the nature of specific tertiary care centers that serve as referral centers for community neurologists who are not familiar with the diagnosis and treatment of uncommon neurological disorders. Neurology residency experiences within tertiary medical centers in the US may not be reflective of future clinical exposure as only 24% of neurologists practice within an academic setting (American Academy of Neurology member demographics: www.aan.com/globals/axon/assets/6723.pdf and www.aan.com/globals/axon/assets/4388.pdf). Additional descriptions of resident experiences from smaller more community based neurology residency programs in the US are needed. Fourth, calculation of the prevalence of neurological complaints seen by general neurologists is based upon results from 15–30 years ago. Significant changes in the health care system (creation of health maintenance organizations and rise of neurospecialists and neurohospitalists) have occurred and could make generalization limited. New studies looking at the prevalence of neurological disorders encountered in the ambulatory setting are needed.

This case report does not espouse that the current system of training is better or worse preparation for clinical practice. However, data from this study and previous reports does suggest that neurology residency experiences have not changed despite new policy interventions by the ACGME. Results from this study could influence neurology residency coordinators concerning the proper balance between inpatient and outpatient exposures that is necessary for adequate neurology training.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Tim Lee for his assistance in tabulating the data and Dr. Doulas Larsen for his helpful suggestions.

Funding Sources:

Support came from NIMH (1K23MH081786) (BA), NINR (1R01NR012657 and 1R01NR012907) (BA), and the Dana Foundation (DF10052) (BA).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure Information:

Dr. Ances is currently participating in a clinical trial of anti-dementia drugs sponsored by Pfizer. He also serves on the scientific advisory board for Lilly Pharmaceuticals.

Author Contribution:

Dr. Ances acquired and analyzed the data as well as wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Corboy JR, Boudreau E, Morgenlander JC, Rudnicki S, Coyle PK. Neurology residency training at the millennium. Neurology. 2002;58:1454–1460. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.10.1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D'Esposito M. Profile of a neurology residency. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:1123–1126. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540350117024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fairfax LM, Christmas AB, Green JM, Miles WS, Sing RF. Operative experience in the era of duty hour restrictions: is broad-based general surgery training coming to an end? Am Surg. 2010;76:578–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gill DJ, Freeman WD, Thoresen P, Corboy JR. Residency training the neurology resident case log: a national survey of neurology residents. Neurology. 2007;68:E32–33. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000262059.88365.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jagannathan J, Vates GE, Pouratian N, Sheehan JP, Patrie J, Grady MS, Jane JA. Impact of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education work-hour regulations on neurosurgical resident education and productivity. J Neurosurg. 2009;110:820–827. doi: 10.3171/2009.2.JNS081446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurtzke JF. The current neurologic burden of illness and injury in the United States. Neurology. 1982;32:1207–1214. doi: 10.1212/wnl.32.11.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacDonald BK, Cockerell OC, Sander JW, Shorvon SD. The incidence and lifetime prevalence of neurological disorders in a prospective community-based study in the UK. Brain. 2000;123 ( Pt 4):665–676. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.4.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maddison P. Neurology training in the United Kingdom: a diagnostic analysis of over 5000 patients. J Neurol. 2005;252:605–607. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0682-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menken M. The ambulatory workload of office-based neurologists: implications of the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:379–381. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1996.00550040119023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore FG, Chalk C. How well does neurology residency mirror practice? Can J Neurol Sci. 2005;32:472–476. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100004467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ringel SP, Vickrey BG, Keran CM, Bieber J, Bradley WG. Training the future neurology workforce. Neurology. 2000;54:480–484. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.2.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rose AS. Graduate training in neurology. An assessment based on the opinions of 80 neurologists in private practice. Arch Neurol. 1971;24:165–168. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1971.00480320093009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roses RE, Foley PJ, Paulson EC, Pray L, Kelz RR, Williams NN, Morris JB. Revisiting the rotating call schedule in less than 80 hours per week. J Surg Educ. 2009;66:357–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuh LA, Adair JC, Drogan O, Kissela BM, Morgenlander JC, Corboy JR. Education research: neurology residency training in the new millennium. Neurology. 2009;72:e15–20. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000342389.60811.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shin S, Britt R, Doviak M, Britt LD. The impact of the 80-hour work week on appropriate resident case coverage. J Surg Res. 2010;162:33–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]