Abstract

Cells perform wide varieties of functions that are facilitated, in part, by adopting unique shapes. Many of the genes and pathways that promote cell fate specification have been elucidated. However, relatively few transcription factors have been identified that promote shape acquisition after fate specification. Here we show that the Nkx5/HMX homeodomain protein MLS-2 is required for cellular elongation and shape maintenance of two tubular epithelial cells in the C.elegans excretory system, the duct and pore cells. The Nkx5/HMX family is highly conserved from sea urchins to humans, with known roles in neuronal and glial development. MLS-2 is expressed in the duct and pore, and defects in mls-2 mutants first arise when the duct and pore normally adopt unique shapes. MLS-2 cooperates with the EGF-Ras-ERK pathway to turn on the LIN-48/Ovo transcription factor in the duct cell during morphogenesis. These results reveal a novel interaction between the Nkx5/HMX family and the EGF-Ras pathway and implicate a transcription factor, MLS-2, as a regulator of cell shape.

Keywords: Caenorhabditis elegans, tubulogenesis, morphogenesis, cytoskeleton

Introduction

Many cell types that are commonly found throughout the animal kingdom have quite remarkable shapes. For example, neurons form highly elaborate axonal and dendritic processes to construct networks that support the many functions of the nervous system. The shapes of neurons can vary tremendously depending on the function of the neuron and the distance between the innervating target and the cell body (Kanning et al., 2010; Marin et al., 2006; Meinertzhagen et al., 2009). Glial cells, which ensheath neurons, can adopt elongated or stellate shapes depending on the functions and shapes of the associated neurons (Mason et al., 1988; Oikonomou and Shaham, 2011). Epithelial cells, which line our organs and external body surfaces, typically are classified as squamous, cuboidal, or columnar in shape (Andrew and Ewald, 2010), but certain epithelial cells, such as tracheal terminal cells in Drosophila and the excretory canal cell in C.elegans, adopt more complex, branched morphologies (Buechner, 2002; Schottenfeld et al., 2010). Although each cell type in the body has a characteristic shape, the relationship between cell fate determination and cell shape acquisition is poorly understood.

The cytoskeleton is the major determinant of cell shape, and all three major components of the cytoskeleton (actin, microtubules, and intermediate filaments) play critical roles. Actin monomers polymerize into long stable filaments and webs that provide mechanical structure to cells (Pollard and Cooper, 2009). Microtubule monomers also polymerize into long rigid filaments that provide structure and serve as tracks for long-range transport of other cellular materials, especially at the growing tips of polarized elongated cells such as neurons (Stiess and Bradke, 2010). Intermediate filaments (IFs) organize into more flexible, rope-like structures that help maintain cell shape and resist mechanical stress (Chang and Goldman, 2004; Goldman et al., 1996; Herrmann et al., 2007). The actin, microtubule and IF-based cytoskeletons are interconnected by various bridging proteins, such as formins and plakins (Chesarone et al., 2010; Leung et al., 2002), and work together to establish and maintain cell shape.

Transcription factors play key roles in specifying cell fates and in promoting subsequent steps of terminal differentiation, and thus must ultimately influence the cytoskeleton to confer cell-type appropriate shapes. Indeed, a few transcription factors appear dedicated specifically to the control of cell shape. For example, transcription factors of the Snail family drive cell shape changes during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition by repressing E-cadherin and other epithelial-specific genes (Peinado et al., 2007). The Drosophila zinc finger transcription factor shavenbaby (svb)/ovo promotes formation of specialized epidermal appendages (denticles) by upregulating multiple genes important for re-organization of the actin cytoskeleton and the extracellular matrix (Chanut-Delalande et al., 2006; Payre et al., 1999). Ovo function appears to be conserved, since the mouse ovo gene, Movo1, also promotes formation of specialized epidermal appendages (hair follicles) (Dai et al., 1998). However, defects in cell fate determination vs. terminal differentiation can be difficult to distinguish in many systems, and few other transcription factors have been identified that function specifically in shape determination downstream of fate specification.

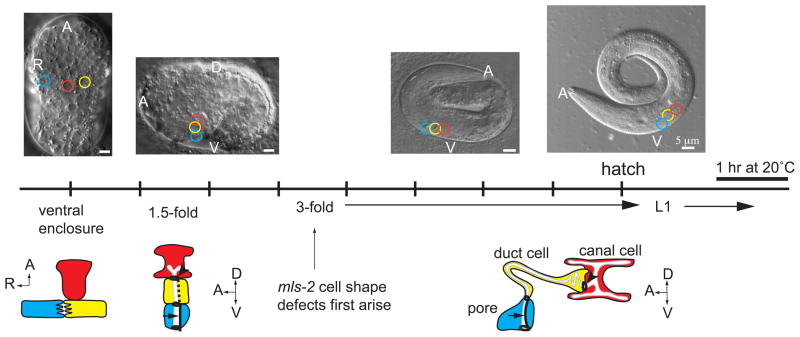

The C.elegans excretory (renal-like) system contains three distinct cell types that adopt unique shapes (Abdus-Saboor et al., 2011; Buechner, 2002; Nelson et al., 1983). All three cells of the excretory system (canal, duct, and pore) are unicellular epithelial tubes that connect in tandem via apico-lateral junctions (Fig. 1). Unicellular tubes are single cells that form tubes by wrapping or hollowing mechanisms (Kamei et al., 2006; Lubarsky and Krasnow, 2003; Rasmussen et al., 2008). The canal cell is the largest cell in the worm and adopts an H-like shape, with four hollow canals that extend the entire length of the worm’s body (Buechner, 2002). The duct and pore are much shorter in length and connect the canal cell to the outside environment (Fig. 1). The duct has a distinctive asymmetric shape, and the region of the duct that connects to the pore is narrow in diameter similar to an axonal extension. The pore has a more regular, conical shape (Fig. 1). Thus the cells of the excretory system provide a model to investigate how epithelial cells adopt specialized shapes.

Figure 1. Timeline of excretory system development.

Schematics of excretory canal cell (red), duct (yellow), and pore (blue) at different developmental stages. DIC images correspond to developmental stage listed on timeline; colored circles on the DIC images represent positions of the canal, duct, and pore. Dark black lines indicate apical junctions. Dotted line, duct auto-fusion. Arrow, pore autocellular junction. Arrowhead, duct-canal cell intercellular junction. Schematics are modified from (Abdus-Saboor et al., 2011). EGF-Ras-ERK-dependent duct vs. pore cell fate specification occurs just prior to the 1.5-fold stage (Abdus-Saboor et al., 2011). The duct elongates extensively between the 1.5-fold and early 3-fold stages (Stone et al., 2009).

The excretory duct and pore develop from initially equivalent precursors that adopt distinct fates in response to EGF-Ras-ERK signaling (Abdus-Saboor et al., 2011; Sulston et al., 1983; Yochem et al., 1997). The duct and pore fates are distinguished by several properties. For example, during migration of the precursors to the midline, the duct takes a canal proximal position, while the pore moves ventrally (Fig. 1). Both cells form unicellular tubes via a wrapping process, but the duct subsequently fuses its autocellular junction while the pore retains its autocellular junction (Stone et al., 2009). During morphogenesis, the duct elongates more extensively than the pore and adopts its unique, asymmetric shape. The duct also expresses the transcription factor LIN-48, an ortholog of Drosphila svb/ovo that influences duct position and/or length (Wang and Chamberlin, 2002).

Here we show that the Nkx5/HMX transcription factor MLS-2 promotes cell shape acquisition in the C.elegans excretory duct and pore. MLS-2 cooperates with the EGF-Ras pathway to promote lin-48/ovo expression, but MLS-2 must have additional relevant targets since the cell shape defects of mls-2 mutants are more severe than those of lin-48 mutants. The roles we identified for MLS-2 in epithelial tube cell development expand the role of Nkx5/HMX proteins, which have traditionally been shown to act within the nervous system (Wang and Lufkin, 2005). MLS-2 promotes differentiation of two other elongated cells in C.elegans, the AWC neuron and the CEP sheath glial cell (Kim et al., 2010; Yoshimura et al., 2008). Therefore, MLS-2 may have a core function in promoting morphogenesis and terminal differentiation in cells that adopt elongated shapes.

Materials and Methods

Strains and alleles

Bristol N2 was the wild-type strain. Strains were maintained and manipulated by standard methods unless otherwise noted. Mutant alleles used are III: mpk-1(ku1), lin-48(sa469). IV: eor-1(cs28), let-60(n1046), lin-1(n304). X: lon-2(e678), mls-2(cc615), mls-2(cs71). Balancers used are: hT2[qIs48] (I; III), mIn1[mIs14 dpy-10(e128)] (II), or nT1[qIs51] (IV, V)). Transgenes used are: jcIs1 (AJM-1::GFP) (Koppen et al., 2001), saIs14 (lin-48p::GFP) (Johnson et al., 2001), wIs78 (AJM-1::GFP) (Koh and Rothman, 2001), csEx146 (lin-48p::mcherry) (Abdus-Saboor et al., 2011), qpIs11 (vha-1p::GFP) (Mattingly and Buechner, 2011), qnEx59 (dct-5p::mcherry) (Abdus-Saboor et al., 2011). csIs55 (GFP::MLS-2) was generated from a pYJ59-containing array (Jiang et al., 2005) by gamma-irradiation-induced integration.

EMS Mutagenesis Screen

Wild-type animals were mutagenized with 50 mM EMS as described previously (Brenner, 1974), and allowed to self-fertilize. F1 progeny were picked to individual plates. From each F1 plate, 8 F2 progeny were picked to individual ksr-2(RNAi) plates, and F3 progeny were screened for rod-like lethal larvae. Mutants were isolated by picking live siblings of rod-like lethal larvae and allowing them to self fertilize. 9 mutants with a rod-like lethal phenotype of greater than 15% penetrance were kept for further analysis. ksr-2(RNAi) was performed to generate a sensitized background for identifying ksr-1-like mutations. Three ksr-1 alleles (cs66, cs74, cs76) were obtained that showed phenotypes that strongly depended on ksr-2(RNAi), as expected based on the known redundancy between the ksr-1 and ksr-2 paralogs (Ohmachi et al., 2002). All other mutants showed phenotypes that were independent of ksr-2(RNAi).

Mapping and complementation tests

Genetic mapping and complementation tests were performed using standard methods. All mutations were roughly mapped by crossing mutant hermaphrodites with males carrying a balancer chromosome marked with GFP. Green hermaphrodite progeny of either the genotype m/+; Bal/+ (where m = mutation and Bal=balancer) or m/Bal were picked to individual plates and allowed to self-fertilize. Rod-like lethal progeny segregating from these animals were examined for GFP expression to assess presence of the balancer chromosome. Animals that segregated only non-GFP rods were presumed to be of the genotype m/Bal. Mutations were then fine-mapped to specific chromosomal regions and candidate loci by further two-factor and/or three-factor linkage mapping.

cs66 mapped close to dpy-6 on the X chromosome. cs66, cs74, and cs76 all showed strong genetic interactions with ksr-2(RNAi) and failed to complement ksr-1(n2526). cs67 mapped close to unc-29 on chromosome I and failed to complement egg-6(ok1506) (Mancuso et al., 2012). cs71 mapped close to lon-2 on the X chromosome and failed to complement mls-2(cc615). cs72 mapped close to unc-24 on chromosome IV and failed to complement vha-5(ok1588). cs73 mapped close to bli-3 on chromosome I and failed to complement let-124(h276). This locus has been re-named lpr-1 (lipocalin-related-1) (Stone et al., 2009). cs75 mapped close to dpy-20 on chromosome IV and failed to complement let-60(sy101sy127). Genomic sequencing revealed a single G-to-A nucleotide change within the let-60/Ras coding region, leading to an Isoleucine to Phenylalanine amino acid change at codon 120. cs127 mapped approximately 3 cM away from dpy-20 on chromosome IV and failed to complement lin-3(n1059).

Marker Analysis and Imaging

Images were captured by differential interference contrast (DIC) and epi-fluorescence microscopy using a Zeiss Axioskop and Hamamatsu C5985 camera, or by confocal microscopy using a Leica SP5. Images were processed for brightness and contrast using Photoshop or ImageJ.

Duct and pore measurements were performed using ImageJ software with worms expressing AJM-1::GFP, which marks the pore autocellular junction (AJ) and the duct-canal junction. To measure the height of the pore AJ, a straight line was drawn in ImageJ from the base of the pore AJ to the top the pore AJ. To measure the duct length, a straight line was drawn in ImageJ from the top of the pore AJ to the duct-canal junction.

To visualize expression of MLS-2 in the duct and pore lineages, we generated 3D confocal movies of strains UP2051 (pie-1::mCherry::HIS-58::pie-1utr; his-72pro::HIS-24::mCherry::let-858utr; GFP::MLS-2) and RW10890 (pie-1::mCherry::HIS-58::pie-1utr; his-72pro::HIS-24::mCherry::let-858utr; PAL-1::GFP) as previously described (Murray et al., 2006) on a Leica TCS SP5 resonance-scanning confocal microscope with 0.5 micron z slice spacing and 1.5 minute time point spacing. Temperature was 22.5°C. We used a hybrid blob-slice model and StarryNite (Bao et al., 2006; Santella et al., 2010) for automated lineage tracing and curated the full lineage through the stage when ~600 nuclei are present (bean stage, approximately 275 minutes) with AceTree (Boyle et al., 2006).

Results

An EMS mutagenesis screen for mutants with duct cell abnormalities

Animals mutant for various components of the canonical EGF-Ras-ERK pathway all display a rod-like lethal phenotype associated with absence or abnormal development of the excretory duct cell (Abdus-Saboor et al., 2011; Yochem et al., 1997). To identify additional genes important for duct development, we conducted an EMS mutagenesis screen for rod-like lethal mutants. After screening 3900 haploid genomes, we identified 9 mutants, several of which had incompletely penetrant phenotypes. We used the apical junction marker AJM-1::GFP, which labels the pore autocellular junction, and a duct-specific lin-48 marker to classify these mutants into two phenotypic groups: 1) Mutants with a duct-to-pore fate transformation; and 2) Mutants with apparently normal duct fate specification. Mapping and complementation tests (Materials and Methods) revealed that the first group included alleles of lin-3/EGF, let-60/Ras and ksr-1/Kinase Suppressor of Ras, as expected based on the known role of EGF-Ras signaling. The second group of mutants included alleles of vha-5, lpr-1 (Stone et al., 2009) and egg-6 (Mancuso et al., 2012), which have been described elsewhere.

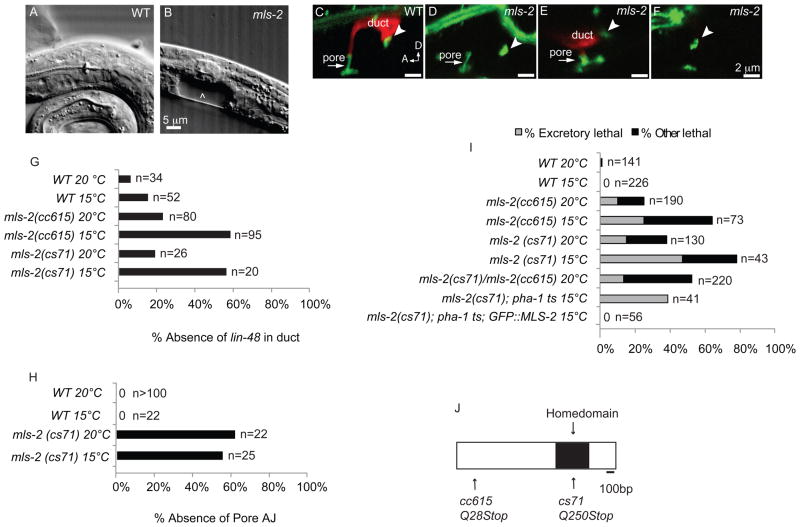

The incompletely penetrant lethal allele cs71 fell into a third category (Fig. 2). cs71 mutants sometimes lacked lin-48 reporter expression, as seen in Ras pathway mutants, but loss of this duct fate marker was not accompanied by duplication of the excretory pore fate (Fig. 2D,F,G). Furthermore, the excretory pore sometimes appeared abnormal or missing based on absence or shortening of its characteristic autocellular junction (Fig. 2E,F,H). Thus, cs71 defined a gene important for both excretory duct and pore development.

Figure 2. mls-2 mutants have incompletely penetrant and cold sensitive lethal excretory system defects.

(A) WT L1 stage larva. (B) mls-2(cs71) L1 stage larva showing fluid accumulation near duct and pore (arrowhead). (C-F) L1 worms with AJM-1::GFP junction marker and lin-48p::mcherry duct marker. Arrowhead, duct-canal cell intercellular junction. (C) WT larva with one duct and one pore. (D) mls-2 mutant with normal AJM-1::GFP but no lin-48 expression. (E) mls-2 mutant with normal lin-48 duct expression and collapsing pore. (F) mls-2 mutant with no lin-48 duct expression and no pore autocellular junction. (G,H) Quantification of marker loss phenotypes in mls-2 mutants. AJ, autocellular junction. (I) Rod-like (excretory) lethality shown as a fraction of total lethality. Other lethality scored as any worm that failed to reach L4 within 4 days. Note: GFP::MLS-2 rescue data scored by DIC microscopy looking for presence or absence of fluid cysts in L1s. Non-transgenic siblings were scored as controls. Complete genotype in this experiment was: mls-2(cs71); pha-1(e2123); Ex[GFP::MLS-2; pha-1(+)]. (J) Protein structure of MLS-2 showing the homeodomain and mutant alleles. cs71 changes a CAA codon (Q250) to TAA (stop).

cs71 is an allele of mls-2

Linkage mapping placed cs71 near the mls-2 gene on the X chromosome. mls-2(cc615) null mutants showed a similar rod-like lethal phenotype, and cs71 and cc615 failed to complement (Fig. 2I). cs71 mutants contained a nonsense mutation in the mls-2 coding region (Fig. 2J). In addition, a translational GFP::MLS-2 reporter completely rescued cs71 lethality (Fig. 2I). We conclude that cs71 is an allele of mls-2.

mls-2 encodes a homeodomain transcription factor that belongs to the Nkx5/HMX superfamily (Jiang et al., 2005). Most members of the Nkx5/HMX family have the HMX motif [A/S]A[E/D]LEAA[N/S] located immediately downstream of the homeodomain (Wang and Lufkin, 2005; Yoshiura et al., 1998), but MLS-2 and its closest relative, the chick SOHo1 protein, both lack the HMX motif (Deitcher et al., 1994). Accordingly, it has been suggested that MLS-2 be considered a member of the Nkx5 family instead of HMX (Yoshimura et al., 2008). In sea urchins, zebrafish, fruit flies, and mice, members of the Nkx5/HMX family are expressed in the developing central nervous system and sensory organs (Gongal et al., 2011; Martinez and Davidson, 1997; Wang et al., 2000). The function of Nkx5/HMX family members has not diverged substantially between species as Drosophila HMX can fully rescue the otic vesicle defects of hmx-2/3 null mice (Wang et al., 2004). Consistent with roles in the nervous system, C.elegans MLS-2 is expressed predominantly in neurons and glial cells (see below), and MLS-2 is required for differentiation and morphogenesis of the AWC chemosensory neurons and the CEP sheath glial cells (Kim et al., 2010; Yoshimura et al., 2008).

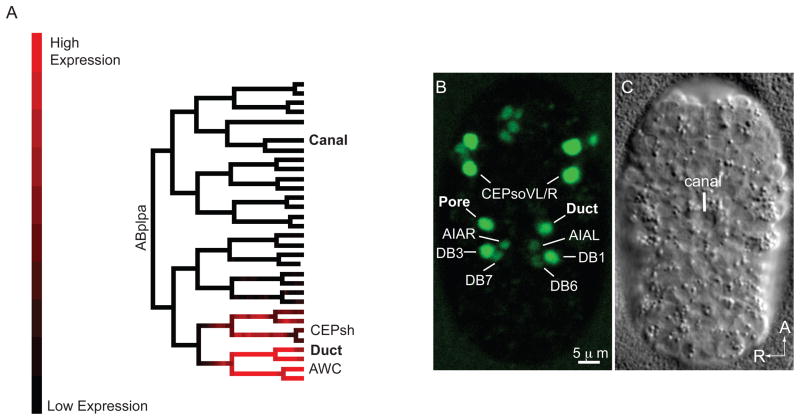

MLS-2 is expressed in the duct and pore lineages

Since mls-2 promotes duct and pore cell development, we asked if the expression pattern of MLS-2 was consistent with a direct role for MLS-2 in these cells. To visualize MLS-2 expression we used csIs55, an integrated version of the GFP::MLS-2 translational reporter that completely rescued mls-2 lethality (Fig. 2I). To gain a complete picture of the MLS-2 expression pattern during embryogenesis, we analyzed confocal time-lapse movies of three developing embryos expressing GFP::MLS-2 and a nuclear histone::mcherry marker (Material and Methods). GFP::MLS-2 expression became detectable around the 50-cell stage of embryogenesis and was restricted to specific, reproducible sublineages of the AB blastomere, most of which gave rise to neuronal and/or glial descendants (Fig. 3 and Supplemental Fig. 1). GFP::MLS-2 was also expressed in the duct and pore lineages, but was never observed in the canal cell (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. mls-2 is expressed in the duct and pore cell lineages.

(A) Lineage tree showing florescence intensity of GFP::MLS-2 expression from 3D automated lineage analysis. Only 1 of 3 embryos that were lineaged is shown here. Only the ABplpa lineage is shown, but GFP::MLS-2 is symmetrically expressed in the ABprpa lineage, which gives rise to the excretory pore. See Supplemental Fig.1 for complete lineage analysis of all 3 embryos. (B) Ventral enclosure embryo expressing GFP::MLS-2, and (C) corresponding DIC image. Identities of some nuclei are indicated. CEPsh nuclei are dim and not visible at this stage. AWC nuclei are not in plane of focus. The pair of nuclei directly above the CEPsoVL/R nuclei are the sisters of the CEPsoVL/R that are fated to die (Sulston et al., 1983). The DB1/DB3 ventral cord motor neurons are sisters of the duct and pore, respectively. AIAL/R are amphid inter-neurons and DB6/DB7 are ventral cord motor neurons; expression in these cells initiates at this stage and is very faint.

In 3/3 movies, we saw that expression of GFP::MLS-2 initiated in the grandparents of the duct and pore cells (Fig. 3A). GFP::MLS-2 expression persisted in the duct and pore cells through the ventral enclosure (Fig. 3B) and 1.5-fold stages of embryonic development, during which time fates are specified via EGF-Ras-ERK signaling and the duct and pore cells stack and form tubes (Abdus-Saboor et al., 2011). By the first larval stage of development, when the duct and pore cells have achieved their mature morphologies, GFP::MLS-2 was no longer detected in the duct and pore cells (data not shown). An MLS-2 polyclonal antibody showed the same expression pattern in the duct and pore cells as GFP::MLS-2 (Abdus-Saboor et al., 2011) and (data not shown). We conclude that the temporal and spatial expression pattern of MLS-2 is consistent with MLS-2 acting cell autonomously to promote duct and pore development.

mls-2 mutants have incompletely penetrant and cold-sensitive lethal excretory system defects

Although both mls-2(cs71) and mls-2(cc615) appear to be null alleles since they truncate or eliminate the protein, their lethal and duct marker phenotypes were incompletely penetrant and cold-sensitive (Fig. 2G,I). The pore junction phenotype was also incompletely penetrant but was not cold-sensitive (Fig. 2H). In addition to the incompletely penetrant early L1 excretory arrest, some mls-2 mutants arrested as larvae without noticeable excretory defects (Fig. 2I). MLS-2 is required for ventral CEP sheath glia morphogenesis, and approximately 20% of worms with ablated ventral sheath glial cells arrest as early larvae (Yoshimura et al., 2008). Therefore, the other non-excretory larval arrest seen in mls-2 mutants could be the result of glial defects. MLS-2 is also required for differentiation of the AWC neurons, but no lethality is associated with loss of the AWC neurons (Kim et al., 2010). Although the duct and pore are closely related in lineage to the ventral CEP sheath glial cells and the AWC neurons (Fig. 3A), mls-2 mutants fail to express differentiation markers for each cell type with varying levels of penetrance, suggesting independent roles for MLS-2 in each cell. The incomplete penetrance of mls-2 null mutants suggests that there are redundant factors that work in parallel to MLS-2 to promote excretory system development. The fact that presumptive null alleles are cold sensitive suggests that the process that requires MLS-2 is cold-sensitive, and not the specific alleles.

mls-2 cooperates with the EGF-Ras pathway to promote duct differentiation and lin-48/ovo expression

To address possible redundancy between MLS-2 and other related homeodomain factors, we took a candidate based approach. We screened 9 of the gene products most related by sequence to MLS-2 by RNA-mediated interference (RNAi). We observed no enhancement of mls-2 excretory phenotypes with this strategy (Supplemental Fig. 2), although we cannot exclude the possibility of inefficient RNAi knockdown; RNAi generally works very poorly in the excretory system (Rocheleau et al., 2008). We also made double mutants between mls-2 and three other related homeodomain genes for which mutants exist, but this too yielded no enhancement of the mls-2 excretory phenotype (Supplemental Fig. 2). However, a more unbiased genome-wide RNAi screening approach identified two chromatin modifying factors, pbrm-1 and tag-298, that greatly enhanced mls-2 rod-like lethality (IA and K. Howell unpublished). pbrm-1 has been previously shown to suppress the multi-vulva phenotype of let-60 Ras(n1046 gf) and also interact with other Ras pathway effectors in the vulva (Lehner et al., 2006).

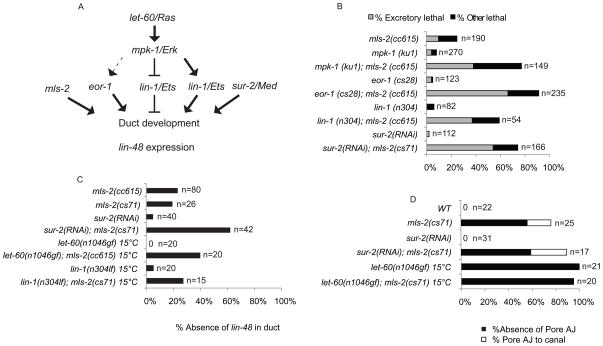

We asked if combining mls-2 with mutants in the EGF-Ras-ERK pathway could enhance the excretory-related lethality of mls-2 (Fig. 4). Specifically, we examined hypomorphic mutants for mpk-1/ERK, which is the terminal kinase in the EGF-Ras pathway (Wu and Han, 1994) and null mutants for lin-1/Ets, a downstream transcription factor (Beitel et al., 1995). In addition, we examined a null mutant for the nuclear factor eor-1 and RNAi for sur-2; these factors act redundantly downstream of MPK-1/ERK (Howard and Sundaram, 2002; Singh and Han, 1995; Tuck and Greenwald, 1995). mpk-1/ERK, lin-1/Ets, eor-1, and sur-2 single mutants all had a weakly penetrant lethal phenotype (Fig. 4B). However, when these mutants were combined with mls-2 mutants, there was a great enhancement of both excretory and total lethality (Fig. 4B). These data suggested that mls-2 cooperates with the EGF-Ras-ERK pathway to promote excretory duct development.

Figure 4. mls-2 cooperates with the EGF-Ras-ERK pathway to promote duct differentiation and lin-48/ovo expression.

(A) EGF-Ras-ERK signaling pathway downstream of let-60/Ras. eor-1, lin-1/ETS, and sur-2/Med23 are downstream nuclear effectors. mls-2 acts downstream or parallel to the EGF-Ras-ERK pathway. (B) Rod-like (excretory) lethality shown as a fraction of total lethality. Other lethality scored as any worm that failed to reach L4 within 4 days. Experiments performed at 20°C. (C) Percentage of L1 worms that lacked lin-48p::GFP expression in duct. Note: let-60(n1046) and lin-1(n304) worms frequently had two lin-48p::GFP positive nuclei instead of one. (D) Percentage of L1 worms that lacked a pore autocellular junction and worms that had a pore AJ junction connected directly to the canal cell (Pore AJ to canal), as scored with AJM-1::GFP. Note: let-60(n1046) and let-60(n1046); mls-2(cs71) were scored at late 3-fold instead of L1. mls-2 alone and in combination with sur-2 (RNAi) assessed at 20°C. let-60(n0146) alone and in combination with mls-2 assessed at 15°C. Note: eor-1(cs28) (Rocheleau et al., 2002) and lin-1(n304)(Beitel et al., 1995) are null alleles; mpk-1(ku1)(Lackner and Kim, 1998) is a hypomorphic allele. Experiments performed at 20°C unless otherwise indicated.

Importantly, we found no evidence for defects in duct vs. pore cell fate specification in mls-2 mutants. Although many mutants lacked markers indicative of the duct or pore cell fate, in no case did we observe duplication of either fate; thus, apparent loss of one cell type was not associated with conversion to the other. mls-2 enhanced defects in duct terminal differentiation, as reflected by enhanced loss of the lin-48 duct marker in a sur-2 background (Fig. 4C). mls-2 did not suppress the pore-to-duct fate transformations of let-60 ras gain-of-function (gf) mutants (Fig. 4D), but did reduce lin-48 marker expression in let-60(gf) and lin-1 backgrounds (Fig. 4C). These data placed mls-2 genetically downstream or in parallel to the EGF-Ras-ERK pathway with respect to turning on lin-48 in the duct cell (Fig. 4A). Thus, mls-2 cooperates with EGF-Ras-ERK to promote terminal differentiation of the excretory duct cell.

mls-2 affects duct and pore tube cell shape

To better understand the mls-2 mutant phenotype, we used additional markers to visualize the shapes of excretory system cells in mls-2 mutants. To visualize the canal cell, we used the vha-1p::GFP marker, which labels the entire cytoplasm of this cell (Mattingly and Buechner, 2011). In mls-2 mutants, the canal cell extended its canals normally the entire length of the worm, and fluid rarely accumulated within the canal lumen (3/104) (Supplemental Fig. 3), suggesting that mls-2 excretory lethality is not the result of canal cell defects.

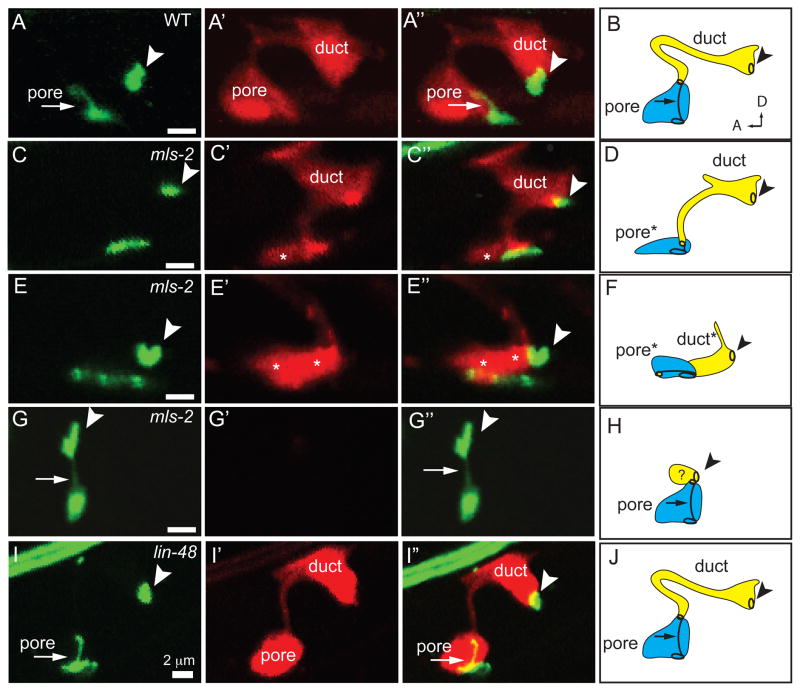

We visualized the cytoplasm of the duct and pore cells with dct-5p:mcherry in combination with AJM-1::GFP (Fig. 5). The duct and pore cells in mls-2 mutants frequently had abnormal globular shapes rather than their normal elongated morphologies (Fig. 5C-H). These cell shape defects were variable, with individual animals exhibiting defects in only the pore (Fig. 5C), only the duct (Fig. 5G), or in both cells (Fig. 5E). mls-2 mutants scored with lin-48p::mcherry and AJM-1::GFP also had variable defects, with either the duct (Fig. 2D), pore (Fig. 2E), or both cells affected (Fig. 2F). Pore cell shape defects were strongly correlated with absence of the pore autocellular junction. In mutants where only the pore cell was affected, the duct often reached to the ventral epidermis (Fig. 5C); this phenotype was compatible with animal survival. In rare mls-2 mutants where only the duct cell was affected, the pore cell appeared to connect directly to the canal cell, and the dct-5p::mcherry marker was not expressed in the duct or pore cells (Fig 5G). Therefore, it was difficult to define the position of the duct cell with this particular phenotype, but we hypothesize that the duct cell either failed to elongate or was displaced. In summary, mls-2 affects the shape of both the excretory pore and duct cells.

Figure 5. mls-2 affects duct and pore tube shape.

AJM-1::GFP (left column) and dct-5p::mCherry (second column) in early L1s grown at 15°C, lateral view. Third column shows overlay. Fourth column shows schematic interpretation of phenotypes. Arrowhead, duct-canal cell intercellular junction. (A,B) WT; n=20. (C–H) mls-2(cs71); n=25. (C,D) Pore cell collapsed and duct extending ventrally; n=11/25. Note: In both wildtype and mls-2 mutants, the duct sometimes displays a dorsal extension as seen here. (E,F) Both the duct and pore cells collapsed ventrally; n=3/25 (G,H) Pore cell AJ connected to canal cell, with duct cell presumably small or mispositioned; n=5/25. The remaining 6/25 mls-2 mutants looked similar to WT. Asterisks indicate ventral cells with collapsed cell shapes. (I, J) lin-48(sa469); n=15. Duct cell shape appears similar to wild-type. Note: lin-48(sa469) is a strong loss-of-function allele that alters a histidine in the second C2H2 zinc finger (Chamberlin et al., 1999).

mls-2 cell shape defects begin during duct and pore elongation

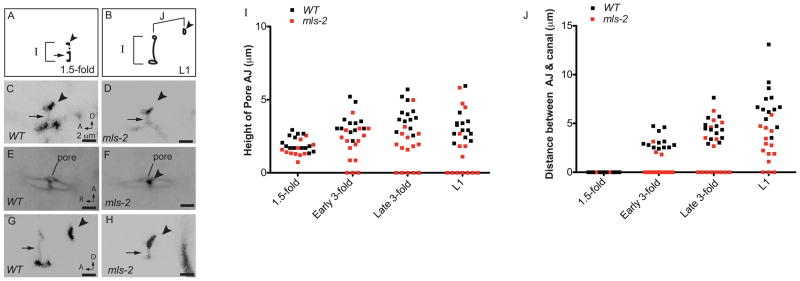

To determine when the mls-2 cell shape and junctional defects began, we measured the length of the pore autocellular junction (AJ) and the distance between the pore AJ and duct-canal junction (an estimate of duct length) at four time-points between the 1.5-fold stage of embryogenesis and the first larval stage of development (Fig. 6). In wildtype worms at the 1.5-fold stage, the duct and pore cells have stacked in tandem and wrapped into tubular structures with simple, block-like shapes (Figs. 1 and 6C) (Abdus-Saboor et al., 2011; Stone et al., 2009). Each cell initially has an autocellular junction, but the duct rapidly auto-fuses to dissolve its junction. mls-2 mutants appeared similar to wild-type at this stage (Fig. 6D), suggesting that the duct and pore had stacked and formed tubes normally. Consistent with the duct and pore stacking normally, at the early 3-fold stage mls-2 mutants had a single ventral pore opening similar to wildtype, as opposed to adjacent non-stacked cells (Abdus-Saboor et al., 2011) (Fig. 6E,F). However, while the cells in wildtype continued to elongate up until the first larval stage, the cells in some mls-2 mutants failed to elongate or actually collapsed and became shorter (Fig. 6G-J). Thus, the mls-2 phenotype first became apparent two hours after the 1.5-fold stage, when the duct and pore cells were beginning to elongate and take distinct shapes.

Figure 6. mls-2 cell shape defects begin around the elongation stage of embryogenesis.

(A, B) Schematics of wild-type AJM-1::GFP junction pattern at 1.5 fold (A) and late 3-fold (B) stages. Parameters measured in I, J are indicated with brackets. Arrowhead, duct-canal cell intercellular junction. (C–H) Excretory duct and pore junction patterns visualized with AJM-1::GFP. Images were inverted in ImageJ for clarity. (C) WT and (D) mls-2 embryos at 1.5-fold, lateral view. (E) WT and (F) mls-2 mid 3-fold embryos, ventral view. Single pore opening lies just adjacent to the G2 and W epidermal cells. Note proximity of the canal cell junction (arrowhead) to the pore opening in F. (G) WT and (H) mls-2 late 3-fold embryos, lateral view. Note no duct elongation in H. (I, J) Measurements of AJ height and distance between AJ and canal cell junction at different time-points. Note: at 1.5-fold stage, height of AJ is duct and pore, and at all other stages, height of AJ is only the pore. Each point is a measurement from a single worm. Early 3-fold corresponds to 2 hours after the 1.5-fold stage. Late 3-fold corresponds to 6 hours after the 1.5-fold stage.

mls-2 mutants have a more severe duct shape phenotype than lin-48 mutants

mls-2 mutants have reduced expression of lin-48 reporters in the excretory duct, suggesting that mls-2 might affect duct cell shape at least in part via upregulation of lin-48. lin-48 is the C. elegans ortholog of Drosophila svb/ovo, which is known to regulate expression of a variety of cytoskeletal genes to control cell shape in the epidermis (Chanut-Delalande et al., 2006). Furthermore, lin-48 mutants were previously described to have defects in duct positioning or shape (Wang and Chamberlin, 2002). We used markers AJM-1::GFP and dct-5p::mcherry to visualize the duct in lin-48 mutants. While the duct cell body appeared somewhat narrower in lin-48 mutants than in wild-type, the duct retained its distinctive process and asymmetric cell shape, and pore morphology was normal (Fig. 5I). The lin-48 mutant phenotype is relatively subtle compared to the mls-2 phenotype, indicating that mls-2 must regulate additional genes in the duct besides lin-48. mls-2 also affects pore shape via mechanisms that are independent of lin-48. lin-48; mls-2 double mutants were not more severe than mls-2 mutants alone (data not shown), suggesting that mls-2 and lin-48 do not have redundant functions in promoting duct cell shape.

Discussion

We have shown that the Nkx5/HMX homeodomain transcription factor MLS-2 promotes terminal differentiation and morphogenesis of the epithelial duct and pore cells in C. elegans. In mls-2 mutants, both cells adopt simple tube shapes as in wild-type, but subsequently fail to elongate to their more complex, mature morphologies. In the duct, MLS-2 cooperates with the EGF-Ras-ERK pathway in turning on the terminal differentiation gene lin-48/ovo. We propose that MLS-2 regulates additional genes important for cytoskeletal organization and cell elongation, and that MLS-2 plays widespread roles in promoting morphogenesis of cells with complex shapes.

mls-2 acts in parallel to the EGF-Ras-ERK pathway to upregulate lin-48/ovo

The EGF-Ras-ERK pathway is used repeatedly throughout metazoan development to promote numerous cell fates. In C. elegans, the EGF-Ras-ERK pathway specifies the excretory duct versus pore fate, and there is a continued requirement for signaling to maintain duct tube architecture after initial fate specification (Abdus-Saboor et al., 2011). How signaling ultimately promotes specific aspects of duct fate such as cell shape, and how continued signaling affects later tube architecture, is unclear. Most effects of EGF-Ras-ERK signaling depend on the combined action of the core downstream transcription factors LIN-1/Ets and EOR-1/BTB-Zinc finger and the Mediator subunit SUR-2, which must then control expression of various other target genes that together influence duct terminal differentiation. MLS-2 cooperates with SUR-2 to turn on one known duct-specific target, the LIN-48/Ovo transcription factor, and acts downstream or in parallel to LIN-1/Ets.

We favor a model whereby MLS-2 works in parallel to the EGF-Ras-ERK pathway and is not itself a target of signaling. Several observations have led us to this conclusion, including: 1) MLS-2 expression begins well before the time that Ras signaling is thought to occur in the duct, and is observed equally in the duct and pore; 2) mls-2 mutants do not have a duct-to-pore fate switch like Ras signaling mutants, and 3) mls-2 mutants have shape defects in both the duct and pore, whereas Ras signaling mutants only affect the duct. We cannot exclude the possibility that Ras signaling enhances MLS-2 expression after it has already been initiated. Neither can we exclude the possibility that the activity of MLS-2 is post-transcriptionally regulated by Ras signaling. Nonetheless, our data are most consistent with the model that MLS-2 and the Ras pathway converge to turn on common targets such as lin-48.

lin-48 plays only a subtle role in shape acquisition and position in the duct cell (Wang and Chamberlin, 2002) and (this work), and therefore is probably just one of a host of target genes downstream of Ras signaling and MLS-2 that promote duct morphogenesis. The Drosophila ortholog of lin-48, shavenbaby (svb), also is upregulated by EGF-Ras-ERK signaling (Payre et al., 1999) and promotes specialized cell shape in the fly epidermis by turning on at least a dozen genes that affect either the cytoskeleton or the extracellular matrix (Chanut-Delalande et al., 2006). Transcriptional upregulation of svb depends on the combined action of at least seven distinct enhancer elements (Frankel et al., 2010; Frankel et al., 2011), and transcription factors that bind directly to these enhancers have not yet been identified. We also do not know if MLS-2 or Ras-regulated transcription factors act directly or indirectly to upregulate lin-48.

MLS-2 may regulate expression of cytoskeletal genes to control duct and pore cell shape

We hypothesize that, in addition to lin-48, MLS-2 targets may include genes more directly involved in cytoskeletal organization. The cold-sensitivity of mls-2 null mutants is consistent with defects in a microtubule-dependent process, since microtubules have been shown to depolymerize at low temperatures in all systems studied, including C. elegans (Chalfie and Thomson, 1982; Melki et al., 1989). Both the actin and microtubule-based cytoskeletons have known roles in cellular elongation contexts (Lloyd and Chan, 2004; Otani et al., 2011; Pollard and Cooper, 2009), so disorganization of either could potentially explain the mls-2 duct and pore shape defects.

Like other organisms, C. elegans has multiple isoforms of actin and tubulin, and many types and isoforms of cytoskeletal bridging proteins, and these various isoforms are expressed in cell-type specific patterns (Bobinnec et al., 2000; Fukushige et al., 1995; Hurd et al., 2010) (Cartier et al., 2006; Fuchs and Karakesisoglou, 2001; McKean et al., 2001; McLean et al., 2008). A given cell’s repertoire of cytoskeletal subunits, combined with its repertoire of bridging proteins, may determine how the different parts of the cytoskeleton work together, contributing to cell-type appropriate morphologies. We currently know very little about which cytoskeletal isoforms are expressed in the excretory duct and pore cells, but predict that the MLS-2 transcription factor promotes expression of a subset of these factors that are important for generating the unique morphologies of these cells.

MLS-2 promotes terminal differentiation of cells with complex shapes

In addition to the duct and pore, mls-2 affects differentiation of the AWC neurons and the CEP sheath glia cells, which all derive from common precursor cells (Kim et al., 2010; Yoshimura et al., 2008) (see Fig. 3A). However, the loss of terminal fate markers occurs at varying penetrance in these different cell types, suggesting that mls-2 plays a specific role in each of these related cell types, and not a general role in the common precursors of the three cell types. In addition to lineage history, one feature shared by all three cell types is a complex shape.

The AWC left and right neurons are a pair of amphid sensory neurons required to chemotax to volatile odors (Bargmann et al., 1993). The AWC neurons have long, unbranched dendrites terminating in elaborate sheet-like cilia that are buried within the amphid glial sheath (Ward et al., 1975). These dendrites elongate via a novel retrograde extension mechanism in which their tips are anchored at the nose while the cell body migrates posteriorly (Heiman and Shaham, 2009). ceh-36 is a terminal selector gene for the AWC neuron (Lanjuin et al., 2003), and mls-2 promotes ceh-36 expression in the AWC neurons (Kim et al., 2010). We note, however, that ceh-36 expression actually precedes mls-2 expression in the embryonic AWC lineages (J.I.M., et al., submitted; and this work), suggesting that mls-2 might be part of a feedback loop that maintains ceh-36 expression in larvae. The AWC neurons are not converted to an alternate neuronal fate in mls-2 mutants, but they often fail to express ceh-36 and other AWC-specific marker genes; cells that do express these markers (and therefore can be visualized) display abnormal dendrite morphology (Kim et al., 2010).

The CEP sheath glial cells envelope the C. elegans nerve ring, which is considered the worm’s brain, and send elongated processes to surround some synaptic sites (Ward et al., 1975). In mls-2 mutants, ventral CEP sheath cells fail to express sheath-specific marker genes and fail to ensheath relevant neurons (Yoshimura et al., 2008). mls-2 is also strongly expressed in CEP socket glia and OLQ sheath glia (Fig. 3B, Supplementary Fig. 3), although its requirements there have not been tested.

The excretory duct and pore tubes have complex cell shapes that are somewhat comparable to those of neurons and glia. The duct and pore, like sheath and socket glia, form unicellular tubes with a hollow interior. The duct also has a long narrow process similar to a neuronal extension. These cells make initial junction attachments to partners at both ends, and then subsequently elongate to maintain those attachments as the embryo elongates and the partners move further and further apart. This phenomenon is similar to the stretch-dependent elongation of many neurons that form synapses early in development and then must maintain those synaptic connections as the animal grows (Smith, 2009). It may also be functionally related to the retrograde extension mechanism of AWC elongation (Heiman and Shaham, 2009).

Many conserved transcription factors control similar developmental processes across distantly related phyla. For example, master transcriptional regulators FoxA, Pax6 and Nkx2.5 specify foregut, eye or heart organ identity in both invertebrate and vertebrate systems (Friedman and Kaestner, 2006; Gehring and Ikeo, 1999; Mango, 2009; Qian et al., 2011), while the Snail family of transcription factors drives epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions (Peinado et al., 2007). In all animals where they have been studied, Nkx5/Hmx transcription factors are expressed primarily in neurons and neuronal support cells such as glia (Wang and Lufkin, 2005). We hypothesize that this expression pattern could reflect a conserved role for MLS-2 and other Nkx5 factors in regulating common sets of cytoskeletal genes important for the process of cellular elongation.

Supplementary Material

Lineage diagrams determined from 3D automated movies of three developing embryos expressing GFP::MLS-2 and a nuclear histone::mcherry marker (Materials and Methods) curated from 50 cells to approximately 600 cells. All three embryos display similar patterns of expression. Scale on left of each lineage diagram represents florescence intensity of GFP::MLS-2.

RNAi by feeding or injection(*) in WT and mls-2 backgrounds of homeodomain genes most related to mls-2 by Clustal W sequence alignments. Mutant alleles were used instead of RNAi for tab-1, ceh-2, and ceh-12. No genetic interactions were observed.

(A,B) vha-1::GFP canal cell marker. (A) WT L1 displaying 1 of 2 canals going entire length of worm’s body. (B) L1 mls-2 mutant with fluid leakage beginning (white lines), and WT canal cell. (C) Fluid never accumulates in canal cell in WT and very rarely accumulates in canal cell in mls-2 mutants. Experiments performed at 20°C.

Highlights.

The Nkx5/HMX homeodomain protein MLS-2 is required for normal elongated cell shape of the C.elegans duct and pore epithelial tubes

MLS-2 cooperates with the EGF-Ras-ERK pathway to turn on lin-48/ovo during duct cell differentiation

mls-2 cell shape defects are more severe than those of lin-48/ovo mutants.

Acknowledgments

We thank Matthew Buechner, Helen Chamberlin, Jun Liu, David Raizen, and the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (University of Minnesota, USA) for providing strains. We thank members of the Sundaram lab for thoughtful suggestions on the manuscript. This work was funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant GM58540 to M.S. I.A. and C.S. were supported in part by T32 GM008216. J.I.M. was partially supported by the NIH (GM083145), by the Penn Genome Frontiers Institute and by a grant with the Pennsylvania Department of Health, which disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations or conclusions. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abdus-Saboor I, Mancuso VP, Murray JI, Palozola K, Norris C, Hall DH, Howell K, Huang K, Sundaram MV. Notch and Ras promote sequential steps of excretory tube development in C. elegans. Development. 2011;138:3545–55. doi: 10.1242/dev.068148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew DJ, Ewald AJ. Morphogenesis of epithelial tubes: Insights into tube formation, elongation, and elaboration. Dev Biol. 2010;341:34–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Z, Murray JI, Boyle T, Ooi SL, Sandel MJ, Waterston RH. Automated cell lineage tracing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2707–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511111103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargmann CI, Hartwieg E, Horvitz HR. Odorant-selective genes and neurons mediate olfaction in C. elegans. Cell. 1993;74:515–27. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80053-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitel GJ, Tuck S, Greenwald I, Horvitz HR. The Caenorhabditis elegans gene lin-1 encodes an ETS-domain protein and defines a branch of the vulval induction pathway. Genes Dev. 1995;9:3149–62. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.24.3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobinnec Y, Fukuda M, Nishida E. Identification and characterization of Caenorhabditis elegans gamma-tubulin in dividing cells and differentiated tissues. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 21):3747–59. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.21.3747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle TJ, Bao Z, Murray JI, Araya CL, Waterston RH. AceTree: a tool for visual analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans embryogenesis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:275. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buechner M. Tubes and the single C. elegans excretory cell. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:479–84. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02364-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartier L, Laforge T, Feki A, Arnaudeau S, Dubois-Dauphin M, Krause KH. Pax6-induced alteration of cell fate: shape changes, expression of neuronal alpha tubulin, postmitotic phenotype, and cell migration. J Neurobiol. 2006;66:421–36. doi: 10.1002/neu.20225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie M, Thomson JN. Structural and functional diversity in the neuronal microtubules of Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Biol. 1982;93:15–23. doi: 10.1083/jcb.93.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin HM, Brown KB, Sternberg PW, Thomas JH. Characterization of seven genes affecting Caenorhabditis elegans hindgut development. Genetics. 1999;153:731–42. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.2.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Goldman RD. Intermediate filaments mediate cytoskeletal crosstalk. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:601–13. doi: 10.1038/nrm1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanut-Delalande H, Fernandes I, Roch F, Payre F, Plaza S. Shavenbaby couples patterning to epidermal cell shape control. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesarone MA, DuPage AG, Goode BL. Unleashing formins to remodel the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:62–74. doi: 10.1038/nrm2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X, Schonbaum C, Degenstein L, Bai W, Mahowald A, Fuchs E. The ovo gene required for cuticle formation and oogenesis in flies is involved in hair formation and spermatogenesis in mice. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3452–63. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.21.3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deitcher DL, Fekete DM, Cepko CL. Asymmetric expression of a novel homeobox gene in vertebrate sensory organs. J Neurosci. 1994;14:486–98. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-02-00486.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel N, Davis GK, Vargas D, Wang S, Payre F, Stern DL. Phenotypic robustness conferred by apparently redundant transcriptional enhancers. Nature. 2010;466:490–3. doi: 10.1038/nature09158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel N, Erezyilmaz DF, McGregor AP, Wang S, Payre F, Stern DL. Morphological evolution caused by many subtle-effect substitutions in regulatory DNA. Nature. 2011;474:598–603. doi: 10.1038/nature10200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JR, Kaestner KH. The Foxa family of transcription factors in development and metabolism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2317–28. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6095-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E, Karakesisoglou I. Bridging cytoskeletal intersections. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1–14. doi: 10.1101/gad.861501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushige T, Yasuda H, Siddiqui SS. Selective expression of the tba-1 alpha tubulin gene in a set of mechanosensory and motor neurons during the development of Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1261:401–16. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(95)00028-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring WJ, Ikeo K. Pax 6: mastering eye morphogenesis and eye evolution. Trends Genet. 1999;15:371–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01776-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman RD, Khuon S, Chou YH, Opal P, Steinert PM. The function of intermediate filaments in cell shape and cytoskeletal integrity. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:971–83. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.4.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gongal PA, March LD, Holly VL, Pillay LM, Berry-Wynne KM, Kagechika H, Waskiewicz AJ. Hmx4 regulates Sonic hedgehog signaling through control of retinoic acid synthesis during forebrain patterning. Dev Biol. 2011;355:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiman MG, Shaham S. DEX-1 and DYF-7 establish sensory dendrite length by anchoring dendritic tips during cell migration. Cell. 2009;137:344–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann H, Bar H, Kreplak L, Strelkov SV, Aebi U. Intermediate filaments: from cell architecture to nanomechanics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:562–73. doi: 10.1038/nrm2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard RM, Sundaram MV. C. elegans EOR-1/PLZF and EOR-2 positively regulate Ras and Wnt signaling and function redundantly with LIN-25 and the SUR-2 Mediator complex. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1815–1827. doi: 10.1101/gad.998402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd DD, Miller RM, Nunez L, Portman DS. Specific alpha- and beta-tubulin isotypes optimize the functions of sensory Cilia in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2010;185:883–96. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.116996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Horner V, Liu J. The HMX homeodomain protein MLS-2 regulates cleavage orientation, cell proliferation and cell fate specification in the C. elegans postembryonic mesoderm. Development. 2005;132:4119–30. doi: 10.1242/dev.01967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AD, Fitzsimmons D, Hagman J, Chamberlin HM. EGL-38 Pax regulates the ovo-related gene lin-48 during Caenorhabditis elegans organ development. Development. 2001;128:2857–65. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.15.2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamei M, Saunders WB, Bayless KJ, Dye L, Davis GE, Weinstein BM. Endothelial tubes assemble from intracellular vacuoles in vivo. Nature. 2006;442:453–6. doi: 10.1038/nature04923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanning KC, Kaplan A, Henderson CE. Motor neuron diversity in development and disease. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2010;33:409–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Kim R, Sengupta P. The HMX/NKX homeodomain protein MLS-2 specifies the identity of the AWC sensory neuron type via regulation of the ceh-36 Otx gene in C. elegans. Development. 2010;137:963–74. doi: 10.1242/dev.044719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh K, Rothman JH. ELT-5 and ELT-6 are required continuously to regulate epidermal seam cell differentiation and cell fusion in C. elegans. Development. 2001;128:2867–80. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.15.2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppen M, Simske JS, Sims PA, Firestein BL, Hall DH, Radice AD, Rongo C, Hardin JD. Cooperative regulation of AJM-1 controls junctional integrity in Caenorhabditis elegans epithelia. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:983–91. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner MR, Kim SK. Genetic analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans MAP kinase gene mpk-1. Genetics. 1998;150:103–17. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanjuin A, VanHoven MK, Bargmann CI, Thompson JK, Sengupta P. Otx/otd homeobox genes specify distinct sensory neuron identities in C. elegans. Dev Cell. 2003;5:621–33. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehner B, Crombie C, Tischler J, Fortunato A, Fraser AG. Systematic mapping of genetic interactions in Caenorhabditis elegans identifies common modifiers of diverse signaling pathways. Nat Genet. 2006;38:896–903. doi: 10.1038/ng1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung CL, Green KJ, Liem RK. Plakins: a family of versatile cytolinker proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:37–45. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd C, Chan J. Microtubules and the shape of plants to come. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:13–22. doi: 10.1038/nrm1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubarsky B, Krasnow MA. Tube morphogenesis: making and shaping biological tubes. Cell. 2003;112:19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01283-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso VP, Parry JM, Storer L, Poggioli C, Nguyen KC, Hall DH, Sundaram MV. Extracellular leucine-rich repeat proteins are required to organize the apical extracellular matrix and maintain epithelial junction integrity in C. elegans. Development. 2012 doi: 10.1242/dev.075135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mango SE. The molecular basis of organ formation: insights from the C. elegans foregut. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:597–628. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin O, Valdeolmillos M, Moya F. Neurons in motion: same principles for different shapes? Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:655–61. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez P, Davidson EH. SpHmx, a sea urchin homeobox gene expressed in embryonic pigment cells. Dev Biol. 1997;181:213–22. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason CA, Edmondson JC, Hatten ME. The extending astroglial process: development of glial cell shape, the growing tip, and interactions with neurons. J Neurosci. 1988;8:3124–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-09-03124.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly BC, Buechner M. The FGD homologue EXC-5 regulates apical trafficking in C. elegans tubules. Dev Biol. 2011;359:59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKean PG, Vaughan S, Gull K. The extended tubulin superfamily. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2723–33. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.15.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean J, Xiao S, Miyazaki K, Robertson J. A novel peripherin isoform generated by alternative translation is required for normal filament network formation. J Neurochem. 2008;104:1663–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinertzhagen IA, Takemura SY, Lu Z, Huang S, Gao S, Ting CY, Lee CH. From form to function: the ways to know a neuron. J Neurogenet. 2009;23:68–77. doi: 10.1080/01677060802610604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melki R, Carlier MF, Pantaloni D, Timasheff SN. Cold depolymerization of microtubules to double rings: geometric stabilization of assemblies. Biochemistry. 1989;28:9143–52. doi: 10.1021/bi00449a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray JI, Bao Z, Boyle TJ, Waterston RH. The lineaging of fluorescently-labeled Caenorhabditis elegans embryos with StarryNite and AceTree. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1468–76. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson FK, Albert PS, Riddle DL. Fine structure of the Caenorhabditis elegans secretory-excretory system. J Ultrastruct Res. 1983;82:156–71. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(83)90050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmachi M, Rocheleau CE, Church D, Lambie E, Schedl T, Sundaram MV. C. elegans ksr-1 and ksr-2 have both unique and redundant functions and are required for MPK-1 ERK phosphorylation. Curr Biol. 2002;12:427–33. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00690-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oikonomou G, Shaham S. The glia of Caenorhabditis elegans. Glia. 2011;59:1253–63. doi: 10.1002/glia.21084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otani T, Oshima K, Onishi S, Takeda M, Shinmyozu K, Yonemura S, Hayashi S. IKKepsilon regulates cell elongation through recycling endosome shuttling. Dev Cell. 2011;20:219–32. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payre F, Vincent A, Carreno S. ovo/svb integrates Wingless and DER pathways to control epidermis differentiation. Nature. 1999;400:271–5. doi: 10.1038/22330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peinado H, Olmeda D, Cano A. Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:415–28. doi: 10.1038/nrc2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard TD, Cooper JA. Actin, a central player in cell shape and movement. Science. 2009;326:1208–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1175862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian L, Wythe JD, Liu J, Cartry J, Vogler G, Mohapatra B, Otway RT, Huang Y, King IN, Maillet M, Zheng Y, Crawley T, Taghli-Lamallem O, Semsarian C, Dunwoodie S, Winlaw D, Harvey RP, Fatkin D, Towbin JA, Molkentin JD, Srivastava D, Ocorr K, Bruneau BG, Bodmer R. Tinman/Nkx2–5 acts via miR-1 and upstream of Cdc42 to regulate heart function across species. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:1181–96. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen JP, English K, Tenlen JR, Priess JR. Notch signaling and morphogenesis of single-cell tubes in the C. elegans digestive tract. Dev Cell. 2008;14:559–69. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocheleau CE, Cullison K, Huang K, Bernstein Y, Spilker AC, Sundaram MV. The Caenorhabditis elegans ekl (enhancer of ksr-1 lethality) genes include putative components of a germline small RNA pathway. Genetics. 2008;178:1431–43. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.084608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocheleau CE, Howard RM, Goldman AP, Volk ML, Girard LJ, Sundaram MV. A lin-45 raf enhancer screen identifies eor-1, eor-2 and unusual alleles of Ras pathway genes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2002;161:121–31. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santella A, Du Z, Nowotschin S, Hadjantonakis A-K, Bao Z. A hybrid blob-slice model for accurate and efficient detection of fluorescence labeled nuclei in 3D. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:580. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schottenfeld J, Song Y, Ghabrial AS. Tube continued: morphogenesis of the Drosophila tracheal system. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:633–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N, Han M. sur-2, a novel gene, functions late in the let-60 ras-mediated signaling pathway during Caenorhabditis elegans vulval induction. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2251–2265. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.18.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DH. Stretch growth of integrated axon tracts: extremes and exploitations. Prog Neurobiol. 2009;89:231–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiess M, Bradke F. Neuronal polarization: the cytoskeleton leads the way. Dev Neurobiol. 2010;71:430–44. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone CE, Hall DH, Sundaram MV. Lipocalin signaling controls unicellular tube development in the Caenorhabditis elegans excretory system. Dev Biol. 2009;329:201–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston JE, Schierenberg E, White JG, Thomson JN. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1983;100:64–119. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuck S, Greenwald I. lin-25, a gene required for vulval induction in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 1995;9:341–357. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Grimmer JF, Van De Water TR, Lufkin T. Hmx2 and Hmx3 homeobox genes direct development of the murine inner ear and hypothalamus and can be functionally replaced by Drosophila Hmx. Dev Cell. 2004;7:439–53. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Lo P, Frasch M, Lufkin T. Hmx: an evolutionary conserved homeobox gene family expressed in the developing nervous system in mice and Drosophila. Mech Dev. 2000;99:123–37. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00488-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Lufkin T. Hmx homeobox gene function in inner ear and nervous system cell-type specification and development. Exp Cell Res. 2005;306:373–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Chamberlin HM. Multiple regulatory changes contribute to the evolution of the Caenorhabditis lin-48 ovo gene. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2345–9. doi: 10.1101/gad.996302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward S, Thomson N, White JG, Brenner S. Electron microscopical reconstruction of the anterior sensory anatomy of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. J Comp Neurol. 1975;160:313–37. doi: 10.1002/cne.901600305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Han M. Suppression of activated Let-60 Ras defines a role of Caenorhabditis elegans sur-1 MAP kinase in vulval differentiation. Genes Dev. 1994;8:147–159. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yochem J, Sundaram M, Han M. Ras is required for a limited number of cell fates and not for general proliferation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2716–22. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura S, Murray JI, Lu Y, Waterston RH, Shaham S. mls-2 and vab-3 Control glia development, hlh-17/Olig expression and glia-dependent neurite extension in C. elegans. Development. 2008;135:2263–75. doi: 10.1242/dev.019547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiura K, Leysens NJ, Reiter RS, Murray JC. Cloning, characterization, and mapping of the mouse homeobox gene Hmx1. Genomics. 1998;50:61–8. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Lineage diagrams determined from 3D automated movies of three developing embryos expressing GFP::MLS-2 and a nuclear histone::mcherry marker (Materials and Methods) curated from 50 cells to approximately 600 cells. All three embryos display similar patterns of expression. Scale on left of each lineage diagram represents florescence intensity of GFP::MLS-2.

RNAi by feeding or injection(*) in WT and mls-2 backgrounds of homeodomain genes most related to mls-2 by Clustal W sequence alignments. Mutant alleles were used instead of RNAi for tab-1, ceh-2, and ceh-12. No genetic interactions were observed.

(A,B) vha-1::GFP canal cell marker. (A) WT L1 displaying 1 of 2 canals going entire length of worm’s body. (B) L1 mls-2 mutant with fluid leakage beginning (white lines), and WT canal cell. (C) Fluid never accumulates in canal cell in WT and very rarely accumulates in canal cell in mls-2 mutants. Experiments performed at 20°C.