Abstract

Epigenetic regulation of chromatin structure is an essential molecular mechanism that contributes to the formation of synaptic plasticity and long-term memory (LTM). An important regulatory process of chromatin structure is acetylation and deacetylation of histone proteins. Inhibition of histone deacetylase (HDAC) increases acetylation of histone proteins and facilitate learning and memory. Nitric oxide (NO) signaling pathway has a role in synaptic plasticity, LTM and regulation of histone acetylation. We have previously shown that NO signaling pathway is required for contextual fear conditioning. The present study investigated the effects of systemic administration of the HDAC inhibitor sodium butyrate (NaB) on fear conditioning in neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) knockout (KO) and wild type (WT) mice. The effect of single administration of NaB on total H3 and H4 histone acetylation in hippocampus and amygdala was also investigated. A single administration of NaB prior to fear conditioning a) rescued contextual fear conditioning of nNOS KO mice, and b) had long-term (weeks) facilitatory effect on the extinction of cued fear memory of WT mice. The facilitatory effect of NaB on extinction of cued fear memory of WT mice was confirmed in a study whereupon NaB was administered during extinction. Results suggest that a) the rescue of contextual fear conditioning in nNOS KO mice is associated with NaB-induced increase in H3 histone acetylation, and b) the accelerated extinction of cued fear memory in WT mice is associated with NaB-induced increase in H4 histone acetylation. Hence, a single administration of HDAC inhibitor may rescue NO-dependent cognitive deficits and afford a long-term accelerating effect on extinction of fear memory of WT mice.

Keywords: histone acetylation, fear conditioning, nitric oxide (NO), extinction

1. Introduction

Fear conditioning is an associative learning paradigm which is used to investigate the formation of short- and long-term memory (STM and LTM). In rodents, fear conditioning occurs by pairing of an aversive unconditioned stimulus (US; footshock) with a neutral sensory cue within a discrete context. Following training and memory consolidation, the previously neutral stimulus acquires the properties of a conditioned stimulus (CS); reexposure to the CS elicits conditioned fear responses (e.g., freezing). The rodent stress hormone corticosterone has a role in the formation of LTM of fear (Kelley, Balda, Anderson, & Itzhak, 2009; Rodrigues, LeDoux, & Sapolsky RM, 2009); this model is considered analogous to the expression of the symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in humans (Mineka & Oehlberg, 2008). Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in conjunction with pharmacotherapies are necessary to ameliorate anxiety disorders and PTSD-like symptoms.

The neural pathways mediating contextual and cued fear conditioning have been extensively studied. Pharmacological and lesion studies suggest roles for the hippocampus and hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP) in contextual fear conditioning (Ahi, Radulovic & Spiess, 2004; Maren & Fanselow, 1995; Phillips & LeDoux, 1992). For cued fear conditioning, direct thalamo-amygdalar projections rapidly transmit sensory information regarding the CS and US to the basolateral amygdala, at which Hebbian LTP and LTM permit the development of conditioned response (Bauer, LeDoux & Nadar, 2001; Rogan, Stäubli & LeDoux, 1997).

Recently, we have shown the requirement of nitric oxide (NO) signaling pathway for the development of contextual fear conditioning. First, mice lacking the neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) gene had major deficits in the acquisition of contextual fear conditioning, while auditory-cued fear conditioning was only slightly impaired (Kelley et al., 2009). Second, the nNOS inhibitor S-methyl-L-thiocitrulline (SMTC) dose-dependently reduced the development of contextual LTM of fear in wild type (WT) mice, and the NO donor molsidomine rescued LTM of contextual fear in nNOS KO mice (Kelley, Anderson & Itzhak, 2010). Third, LTM of visually cued fear conditioning also requires the NO signaling pathway (Kelley, Anderson, Altman & Itzhak, 2011). Both the role of NO signaling in contextual fear conditioning (Resstel, Corrêa & Guimarães, 2008) and the role of NO-cGMP-PKG signaling in auditory-cued fear conditioning (Ota, Pierre, Ploski, Queen & Schafe, 2008; Schafe et al., 2005) have been reported.

Recent studies suggest a role for NO in epigenetic mechanisms relevant to the acetylation of histone proteins (Nott & Riccio, 2009). For instance, NO-induced S-nitrosylation of histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) in neurons causes the release of HDAC2 from the chromatin. The release of HDAC2 increases acetylation of histones surrounding neurotrophin -dependent gene promoters, thereby increasing gene expression (Nott, Watson, Robinson, Crepaldi & Riccio, 2008). Epigenetic regulation of chromatin involves covalent modifications of both DNA and histone proteins. Histones can undergo posttranslational covalent modifications at the N-terminal tails including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ADP-ribosylation, sumoylation and ubiquitination (Shilatifard, 2006). Histone acetylation allows more accessible binding to co-activators and activation of the transcriptional machinery. Several studies have reported the role of histone acetylation in the consolidation of hippocampus-dependent LTM (Guan et al., 2009; Levenson et al., 2004; Vecsey et al., 2007) as well as in the consolidation of lateral amygdala-dependent LTM (Monsey, Ota, Akingbade, Hong & Schafe, 2011). A recent study demonstrated the role of histone acetylation in the hippocampus-infralimbic structures in fear extinction (Stafford, Raybuck, Raybinin & Lattal, 2012).

The present study was undertaken to investigate whether increase in histone acetylation -- by the HDAC inhibitor sodium butyrate (NaB) -- a) rescues the formation of LTM of contextual fear conditioning in nNOS KO mice, and b) accelerates the extinction of contextual and cued fear conditioning in WT and nNOS KO mice. We report that a single systemic administration of NaB a) markedly increased total H3 histone acetylation in the hippocampus and amygdala of nNOS KO but had relatively small effect on H3 histone acetylation in hippocampus of WT mice, b) increased LTM of contextual fear conditioning in nNOS KO but not WT mice, c) accelerated the extinction of cued fear conditioning of WT but not nNOS KO mice and d) accelerated the extinction of cued but not contextual fear conditioning of WT mice. Results suggest that increase in amygdalar and hippocampal histone acetylation a) improves deficits in the acquisition of fear conditioning of nNOS KO mice, and b) has long-term accelerating effect on the extinction of cued fear conditioning of WT mice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

nNOS KO mice were generated on a mixed B6;129S genetic background; the targeted deletion of the α subunit of nNOS resulted in >95% reduction in brain nNOS catalytic activity (Huang, Dawson, Bredt, Snyder, Fishman, 1993). Adult male homozygous nNOS KO mice (B6;129S4-Nos1; 10–12 weeks old), and the parental strains of their WT counterparts (C57BL/6J and 129S1/SvImJ) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine). Our breeding colony, littermate selection, and animal care have been described earlier (Balda, Anderson & Itzhak, 2006). Animal care was in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, National Academy Press, 1996) and was approved by the University of Miami Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2 Effect of NaB on total H3 and H4 histone acetylation levels in hippocampus and amygdala

The aim of this experiment was to investigate the effects of a single administration of NaB on total H3 and H4 histone acetylation in the hippocampus and amygdala of WT and nNOS KO mice. Mice (n=5–7/group) received a single intraperitoneal (IP) injection of either saline (0.9% NaCl) or NaB (1.2g/kg). The dose of NaB was based on studies by Levenson et al. 2004 and Kilgore et al. 2010. After 60min mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and hippocampus and amygdala were freshly dissected, snap-frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C. Histone extractions were prepared as follows. Tissue was resuspended in 5 volumes of Triton extraction buffer (TEB) which comprised phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing Triton X-100 (0.5% v/v), phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (2mM; PMSF), and sodium azide (0.02% w/v; NaN3). The suspension was rocked for 10min on a rocking platform at 4°C, then centrifuged (10,000 × g; 10 min; 4°C) to spin down the nuclei. The supernatant was discarded and the nuclei were washed with half of the volume of TEB as before and again centrifuged. The pellet was resuspended in 2 volumes of HCl (0.2N) and incubated overnight (4°C) to extract the histone fraction. On the following day, the mixture was centrifuged (14,000 × g; 10 min; 4°C); the supernatant was collected and neutralized by a balance buffer containing DTT (Epigentek). Aliquots were taken for determination of protein concentration and the rest was stored at −80°C.

Total H3 and H4 histone acetylation assays were performed according to directions in a solid phase sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (PathScan Sandwich ELISA, Cell Signaling Technology). Essentially, histone extracts were mixed with kit-provided sample buffer and loaded (amygdala, 120 g/ml; hippocampus, 60 g/ml) into a 96-well plate that had wells coated with capture antibody. The plate was incubated overnight at 4°C, with gentle rocking. The following day, wells were washed 4 times with kit-provided wash buffer; the final wash was aspirated out. Histone detection antibody was added, and the plate was incubated for 1h at 37°C. Thereafter the plate was again washed 4 times, and a horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated secondary antibody added. Following a 30min incubation (37°C), the plate was washed as before, and TMB substrate (3,3', 5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine) added. The reaction was allowed to develop for 30min at room temperature, after which kit-provided stop solution was added. Sample absorbance was then determined via a spectrophotometer (450nm).

2.3 Fear conditioning

Fear conditioning training and testing occurred in Plexiglas chambers (30.5 × 30.5 × 43.5 cm; Noldus Information Technology Inc., Leesburg, VA). Each chamber is equipped with a stainless-steel rod floor through which the electric shock is delivered, and an upper control panel containing a video camera, a sound emitter and a white light illuminating one corner of the chamber. The chambers are housed in custom built sound-attenuating cubicles which give the appearance of black walls to the chamber.

Experiments were carried out as we previously described (Kelley et al., 2009; 2010). A fear conditioning training session consisted of placement in the training context (context-A) and after 2 min an auditory cue (2.3 kHz; 70 dB) sounded for 30 sec, co-terminating with a 2 sec footshock (0.35 and 0.75mA). Mice were returned 30 seconds later to the Home cage. Contextual fear conditioning was measured in context-A, and consisted of digitally recording the animal’s percentage of total time spent “freezing” while in the chamber for 3 min; freezing, defined as a complete lack of movement besides respiration (<5% mobility), was calculated by EthoVision v3.1 software (Noldus Information Technology Inc., Leesburg, VA) and expressed as a percentage of either a portion of or the total time in the chamber. Cued fear conditioning was measured in a different context (context-B), and the previously used tone sounded for 2 min after an initial habituation period of 2 min. Context-B utilized a smooth white foam floor covering the shock grid, four opaque white walls, and olfactory enrichment of pure orange extract affixed to the chamber ceiling. Hence visual, tactile, and olfactory cues were employed to differentiate context-A from context-B. Freezing was tested 1h after training for short-term memory (STM), and 24h and 7 days later for LTM. Routinely, all three tested were performed in the same group of mice.

2.3.1. Effect of NaB on acquisition of fear conditioning in nNOS KO and WT mice

nNOS KO (two groups; n=8 per group) and WT (two groups; n=6 per group) mice received IP injections of saline or NaB (1.2g/kg) 60 min before training. In initial experiments, the footshock intensity was 0.75mA. We have previous shown that this intensity of footshock was sufficient to induce contextual fear response in WT but not nNOS KO mice (Kelley et al., 2009). However, because NaB had no effect on acquisition of fear conditioning in WT mice shocked by 0.75mA, a second group of WT mice received either saline (n=7) or NaB (n=8) and then was shocked by a lower intensity footshock (0.35mA). Subsequently, contextual and cued freezing was determined 1 and 24h posttraining and then 7 days posttraining (Table 1).

Table 1.

Experimental design of fear conditioning trials in WT and nNOS KO mice

| Mice/Treatment | Footshock (mA) |

STM | LTM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp. 2.3.1. Acquisition of contextual memory | |||||||

| WT (S) WT (NaB) |

0.35 & 0.75 0.35 & 0.75 |

1h 1h |

24h & 7d 24h & 7d |

||||

| nNOS KO (S) nNOS KO (NaB) |

0.75 0.75 |

1h 1h |

24h & 7d 24h & 7d |

||||

| Exp. 2.3.2. Acquisition, extinction, renewal and re- extinction of contextual and cued memory of WT mice |

Extinction | Renewal | Re-extinction | ||||

| CX | Cue | Cue | Cue | ||||

| WT (S) WT (NaB) |

0.75 0.75 |

1h 1h |

24h & 7d 24h & 7d |

CX-A CX-A |

CX-B CX-B |

CX-A CX-A |

CX-A CX-A |

| Exp. 2.3.3. Acquisition and extinction of cued memory of WT and nNOS KO mice |

Extinction Cue in CX-B |

||||||

| WT nNOS KO |

0.75 0.75 |

N/A | 24h & 7d 24h & 7d |

Saline vs. NaB Saline vs. NaB |

|||

STM, short-term memory; LTM, long-term memory; S, saline; NaB; sodium butyrate; CX, context

2.3.2. Effect of a single pretraining administration of NaB to WT mice on extinction, renewal, and re-extinction of contextual and cued memory

Because NaB had no effect on acquisition of fear response in WT mice, we sought to investigate whether this treatment influences extinction. WT mice received either saline (n=8) or NaB (1.2g/kg) (n=8) 60min pretraining. Mice were trained as described above with a shock intensity of 0.75mA. Acquisition of freezing response was determined 1h, 24h and 7 days posttraining. Extinction training commenced 3 days after the 7-day posttraining test, and lasted for 5 consecutive days. For extinction of contextual memory, mice were reexposed to the training context (A) for 4 min (morning session). For extinction of cued memory, mice were reexposed to context B for a total of 4 min; 2min in the absence of the auditory cue followed by 2 min in the presence of the auditory cue (afternoon session). Typically the two extinction sessions were separated by 3h. A significant reduction in freezing response to the context and cue (extinction) was achieved within 5 days in both groups. On the following day, renewal of cue-dependent freezing was tested in context A. Mice were placed in context A and after 2min the auditory cue sounded (2min). Because renewal occurred in both the saline and NaB groups, re-extinction training commenced the next day. Mice were reexposed daily to context A for a total of 4 min, the final 2 min in the presence of the auditory cue, and extinction of the renewed freezing was monitored (Table 1).

2.3.3. Effect of a single post-extinction training administration of NaB to WT and nNOS KO mice on extinction of cued memory

The experiment described in 2.3.2 investigated the effect of NaB on extinction of contextual and cued fear conditioning in WT mice which received the HDAC inhibitor prior to fear conditioning. The goal of this experiment was to investigate the effect of NaB on extinction of cued fear memory of WT and nNOS KO mice which received the HDAC inhibitor upon the extinction training phase. Contextual fear conditioning was not tested, because nNOS KO mice do not develop contextual fear response in the absence of NaB during the conditioning phase (Fig. 1A).

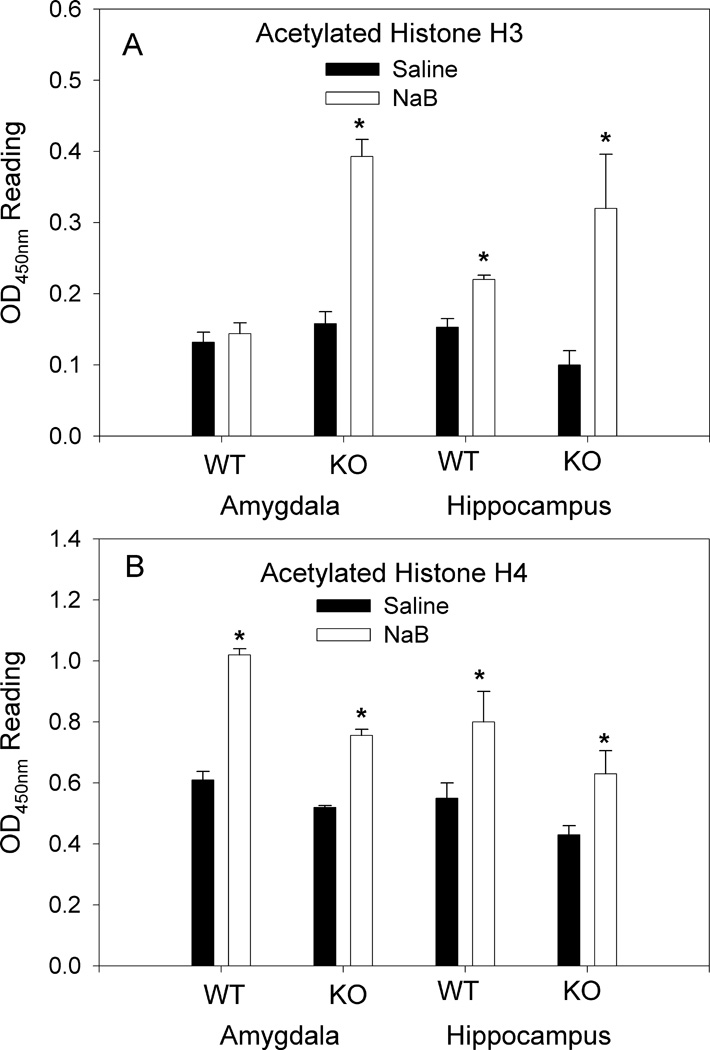

Fig. 1.

Effect of NaB on total H3 and H4 histone acetylation. A. NaB (1.2g/kg) significantly (*p<0.05) increased the levels of H3 acetylation in both the amygdala and hippocampus of nNOS KO mice (saline, n=7; NaB, n=7), and in the hippocampus of WT mice (saline, n=5; NaB, n=5) (*p<0.05); however, NaB had no significant effect on H3 histone acetylation in the amygdala of WT mice. B. NaB (1.2g/kg) significantly (*p<0.05) increased levels of H4 acetylation in amygdala and hippocampus of both WT (saline, n=5; NaB, n=5) and nNOS KO (saline, n=5; NaB, n=5) mice.

WT (n=16) and nNOS KO (n=16) mice were conditioned as described in Section 2.3 with a shock intensity of 0.75mA. All mice were tested for cued freezing 24h and 7 days posttraining. Extinction training commenced 3 days after day-7 posttraining test and lasted for 5 days. On day 1 of extinction training half of the WT mice and half of the nNOS KO mice (n=8 per group) received saline and the other halves of WT (n=8) and nNOS KO (n=8) mice received NaB (1.2g/kg; IP) immediately after the first extinction session and mice were returned to home cage. Extinction of cued memory was conducted by daily exposures to context B for a total of 4 min; 2min in the absence of the auditory cue followed by 2 min in the presence of the auditory cue. On days 2–5 of extinction training mice did not receive any injections.

2.4. Statistical analyses

The levels of total H3 and H4 histone acetylation (saline vs. NaB) in hippocampus and amygdala of each genotype were analyzed by unpaired Student t-test. Results of fear conditioning were analyzed by two-way ANOVA (NaB effect × time effect) or three-way ANOVA (genotype × NaB effect × time effect). When significant, post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparisons test was performed; P<0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of NaB on total H3 and H4 histone acetylation levels in hippocampus and amygdala

3.1.1. H3 histone acetylation

A single administration of NaB (1.2g/kg) to nNOS KO mice resulted in 2.7-fold increase in H3 histone acetylation in the amygdala (t=9.60; p<0.001; DF=12) and 3-fold increase in H3 histone acetylation in the hippocampus (t=3.99; p<0.01; DF=12 (Fig. 1A). A single administration of NaB (1.2g/kg) to WT mice had no significant effect on H3 histone acetylation in the amygdala (t=0.49; p>0.05; DF=8, but resulted in 43±1% increase in H3 histone acetylation in the hippocampus (t=5.08; p<0.01; DF=8) (Fig. 1A).

3.1.2. H4 histone acetylation

NaB (1.2g/kg) increased H4 acetylation by 66% (t=13.57; p<0.01; DF=8) and 40% (t=4.02; p<0.05; DF=8) in amygdala and hippocampus of WT mice, respectively (Fig. 1B). Likewise NaB increased H4 acetylation by 50% (t=4.53; p<0.05; DF=8) and 94% (t=5.71; p<0.01; DF=8) in amygdala and hippocampus of nNOS KO mice, respectively (Fig. 1B). Results suggest that NaB had a marked effect on H3 histone acetylation in nNOS KO mice while the effect on WT mice was reletively low; however, the effect on H4 histone acetylation was not genotype specific.

3.2. Effect of NaB on acquisition of fear conditioning in nNOS KO and WT mice

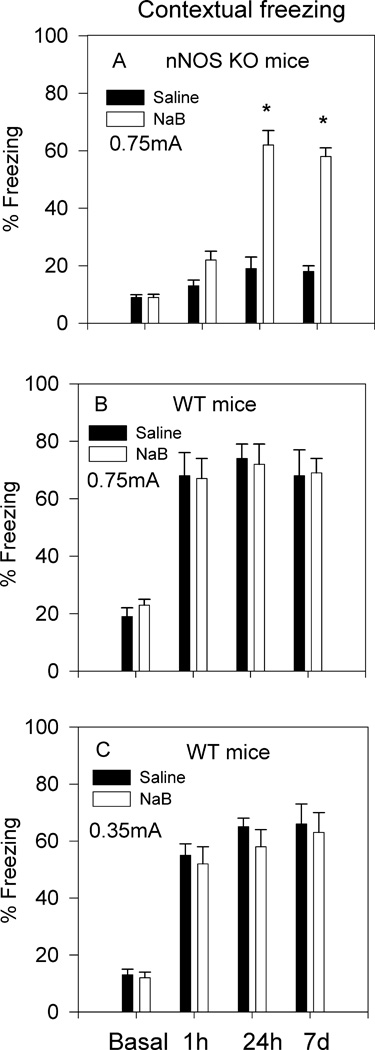

nNOS KO and WT mice received NaB (1.2g/kg) 60 min prior to fear conditioning. Contextual freezing was assessed in the same group of mice 1h, 24h and 7 days posttraining. Two-way ANOVA for the effect of NaB on contextual fear conditioning of nNOS KO mice yielded a significant drug effect F[1,60]=33.45; p<0.001; a significant time effect F[3,60]=26.1; p<0.001; and a significant interaction F[3,60]=4.5; p<0.05. In agreement with our previous findings, training of nNOS KO mice by a single footshock (0.75mA) did not result in significant contextual LTM (Kelley et al., 2009; Fig. 2A). However, an acute administration of NaB prior to training resulted in significant increase in contextual freezing 24h (p<0.01) and 7d (p<0.01) posttraining (Fig. 2A). NaB had no significant effect on STM (1h posttraining) (Fig. 2A). Administration of NaB to WT mice prior to training by a footshock intensity of 0.75mA had no effect on STM and LTM of contextual fear (Fig. 1B). A two-way ANOVA revealed no significant drug effect F[1,40]=2.03; p>0.05; but a significant time effect F[3,40]=28.8; p<0.001; the latter is attributed to the differences between basal and posttraining freezing. Reasoning that the lack of effect of NaB on WT mice may be due to a ceiling effect, we next investigated the effect of a low-intensity footshock (0.35mA). However, results in Fig. 2C suggest that NaB had no effect on contextual fear conditioning elicited by the low intensity footshock. Although % freezing following 0.35mA footshock was somewhat lower (55–65%; Fig. 2C) compared to that following 0.75mA (70–80%; Fig. 2B), NaB did not have any significant effect F[1,49]=2.5; p>0.05. Results suggest that NaB (1.2g/kg) had specific effect on the consolidation of contextual LTM in nNOS KO but not WT mice.

Fig. 2.

Effect of NaB on contextual fear conditioning of nNOS KO and WT mice. A. Pretraining administration of NaB (1.2g/kg) to nNOS KO mice significantly increased contextual freezing 24h and 7d posttraining (*p<0.05). NaB had no significant effect on STM as determined 1h posttraining (saline, n=8; NaB, n=8). B. Pretraining administration of NaB (1.2g/kg) to WT mice that were subsequently conditioned by 0.75mA footshock had no significant effect on freezing response 1h, 24h and 7d posttraining (saline, n=6; NaB, n=6). C. NaB (1.2g/kg) had no effect on freezing response of mice conditioned by 0.35mA footshock (saline, n=8; NaB, n=7). Basal freezing represents % freezing during habituation (pretraining) to the training context (2min). All other data represent % freezing over a 2min time period in all subsequent posttraining tests.

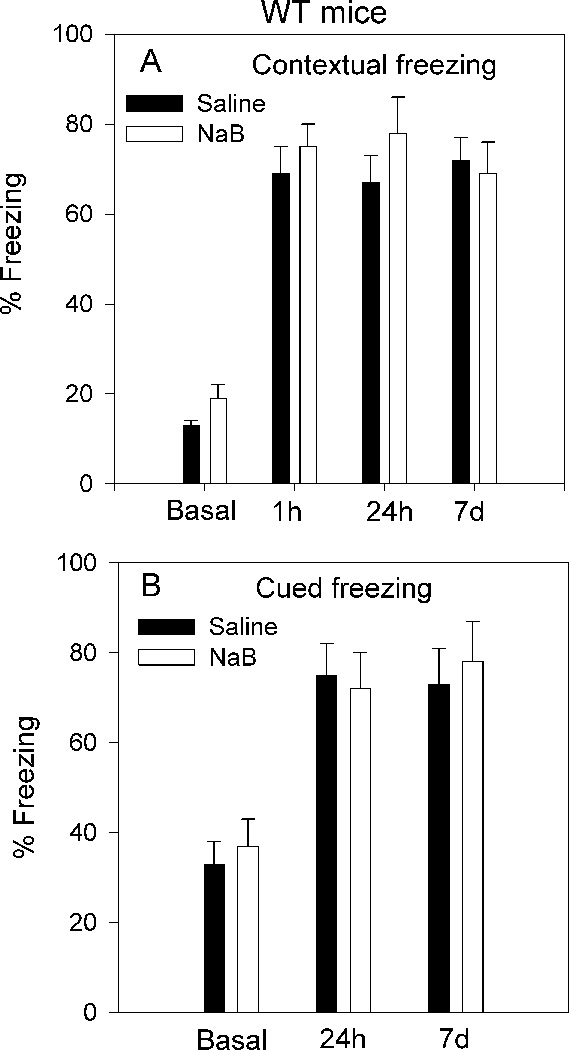

3.3. Effect of pretraining administration of NaB to WT mice on extinction, renewal, and re-extinction of contextual and cued memory

Because NaB had no effect on the acquisition of contextual fear response in WT mice, we sought to investigate whether this treatment influences extinction. WT mice received either saline or NaB (1.2g/kg) 60min pretraining by a single footshock (0.75mA), which coincided with an auditory cue. Results of contextual freezing 1h, 24h and 7d posttraining suggest that NaB had no significant effect; freezing in both groups reached 70–80% (Fig. 3A). Likewise results of cued freezing 24h and 7d posttraining suggest that NaB had no significant effect; freezing in both groups reached 75–85% (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Effect of NaB on acquisition of contextual and cued fear conditioning of WT mice. A. NaB (1.2g/kg) had no significant effect on contextual fear conditioning 1h, 24h and 7d posttraining (footshock intensity 0.75mA). Basal freezing represents % freezing during pretraining habituation to the training context (2min). All other data represent % freezing measured over 2min in all subsequent posttraining tests. B. NaB had no significant effect on cued fear conditioning 24h and 7d posttraining. Basal freezing represents % freezing during habituation to the novel context (B) (2min) before the presentation of auditory cue. All other data represent % freezing during a 2min period occurring while the auditory cue sounded (saline, n=8; NaB, n=8).

Three days after the 7-day test for LTM, extinction training commenced. For extinction of contextual freezing, mice were reexposed daily to the training context (A) for 4 min. For extinction of cued freezing, mice were placed in context B whereupon the auditory cue sounded (2 min) after habituation (2min). Comparison between extinction of contextual freezing in saline and NaB pretreated groups revealed no significant drug effect F[1,55]=0.09; p>0.05; but a significant time effect F[4,55]=4.46; p<0.01 (Fig. 4A). Results suggest that NaB had no significant effect, and by the fifth day of extinction training both groups showed significant reduction in % freezing compared to the first day of extinction training (p<0.05; Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Effect of pretraining administration of NaB to WT mice on extinction, renewal, and re-extinction of contextual and cued memory. Overall timeline: day 1: acquisition of fear conditioning and test for STM (1h posttraining). Days 2 and 7: tests for LTM. Days 10–14: extinction training depicted as days 1–5 in panels A and B; Day 15: renewal effect depicted as day 1 in panel C. days 16–19: extinction of renewal effect depicted as days 2–5 in panel C. A. Extinction training of contextual freezing was conducted in the training context (A). Mice were reexposed daily to the context for 4min. Results represent % freezing during the first 90 seconds. Analysis of the temporal freezing response across each 30 second block of time comprising the 4 min period revealed that peak freezing occurred during the first 90 seconds. Thereafter the freezing response fluctuated as a result of prolonged exploration of the context. No significant differences between the saline and NaB groups were observed. However, both groups showed significantly lower % freezing on day 5 compared to day 1 of extinction training (*p<0.05). B. Results depict % freezing during the 2 min presentation of the auditory cue. There was an overall significant group effect F[1,55]=16.1; p<0.001; and a significant time effect F[4,55]=4.7; p<0.05. On day 2 of extinction training, a significant difference between the two groups was observed (#p<0.05). C. Results depict renewal and re-extinction of freezing in the training context (A). Day 1 represents renewal because it was the first re-exposure to the training context in the presence of the auditory cue. Days 2–5 represent re-extinction. % Freezing (during 2min) in the NaB group was significantly lower than in the saline group on days 4 and 5 (#p<0.05) (saline, n=8; NaB, n=8).

Comparison between extinction of cued freezing in saline and NaB pretreated groups revealed a significant drug effect F[1,55]=16.1; p<0.001; and a significant time effect F[4,55]=4.7; p<0.05. On day 2 of extinction training a significant difference between the two groups was observed (p<0.05; Fig. 4B). Results suggest that NaB had a long-term effect on acceleration of cued fear extinction.

Extinction is known to be context-specific; thus renewal of fear response occurs when the subject is reexposed to the training context in the presence of a previously extinguished fearful cue (Bouton, 2004; Bouton & King, 1983). Following the 5-day extinction training, mice were reexposed to the training context (A) in the presence of the auditory cue. Freezing in the saline and the NaB groups reached to 63±4% and 55±6%, respectively (Fig. 4C). In order to re-extinguish the freezing response, mice were reexposed to context A in the presence of the auditory cue (2 min of silent habituation followed by an additional 2 min with the auditory cue). Comparison between the saline and NaB groups revealed a significant drug effect F[1,55]=22.02; p<0.001; and a non significant time effect F[4,55]=1.13; p>0.05 (Fig. 4C). Although there was no significant time effect, it appears that the freezing response in the NaB group was significantly lower than the saline group on days 4 and 5 (p<0.05; Fig. 4C).

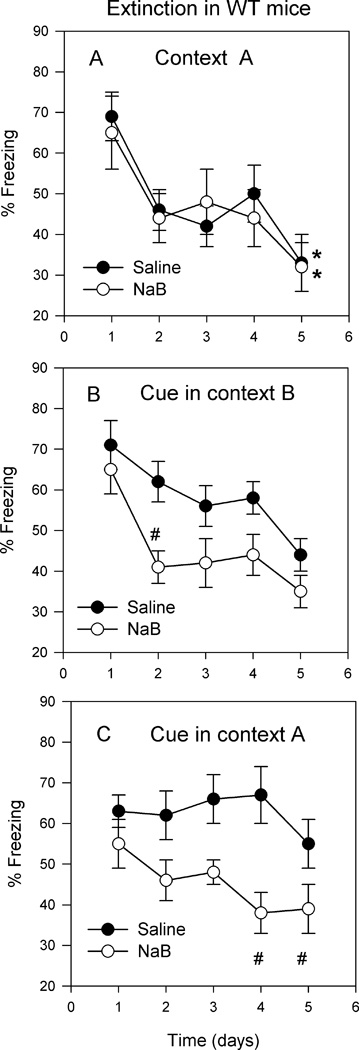

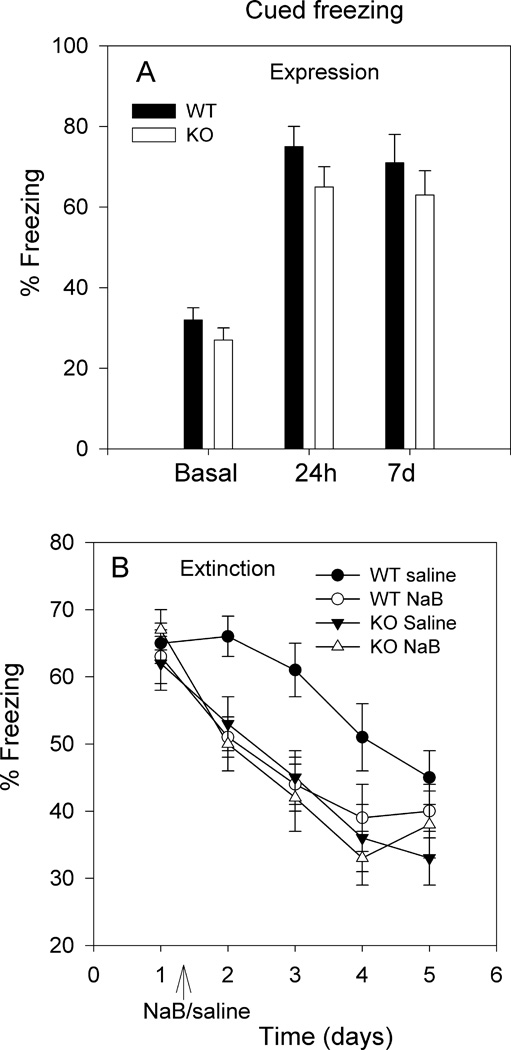

3.4. Effect of a single post-extinction training administration of NaB to WT and nNOS KO mice on extinction of cued memory

This experiment investigated the effect of NaB administration following the first extinction session on cued fear memory in both WT and nNOS KO mice. LTM of cued fear conditioning in nNOS KO mice was similar to that observed in WT mice (Fig. 5A). We performed several post-hoc statistical analyses and we have shown that the small difference between the magnitude of cued fear conditioning of WT and nNOS KO mice is not significant, unless the least-restricted post-hoc LSD test was performed (Kelley et al., 2009). Three days following the day-7 test, mice underwent cue exposure for the purpose of cue extinction; immediately after this session mice received either saline or NaB and then returned to home cage. Mice continued to be exposed to the cue for the next 4 days in the absence of any injections. Results depicted in Fig. 5B suggest that NaB accelerated cue extinction of WT mice but had no effect on nNOS KO mice. A three-way ANOVA revealed a significant drug effect F[1,140]=29.82; p<0.001; a significant genotype effect F[1,140]=27.02; p<0.001 and a significant time effect F[4,140]=137.11; p<0.001. A significant interaction between the three parameters was also observed F[4;140]=5.22; p<0.001. Results confirm the accelerating effect of NaB on the extinction of cued fear memory of WT mice (as observed in Fig. 4B), but also suggest that NaB had no effect on the extinction of cued memory of nNOS KO mice.

Fig. 5.

Cued freezing in WT and nNOS KO mice and the effect of NaB during the extinction phase. WT mice (n=16) and nNOS KO mice (n=16) were fear conditioned as described in section 2.3. A. The expression of cued freezing of WT and KO mice 24h and 7 days posttraining was similar. B. Three days after the day-7 test mice were reexposed to the cue to initiate cue extinction (depicted as day 1 in the X-axis) and then half of the mice from each group (n=8) received saline and half (n=8) received NaB (1.2g/kg). Results show that NaB significantly accelerated the extinction of cued freezing in WT mice but it had no effect on nNOS KO mice. Three-way ANOVA revealed a significant drug effect F[1,140]=29.82; p<0.001; a significant genotype effect F[1,140]=27.02; p<0.001 and a significant time effect F[4,140]=137.11; p<0.001.

4. Discussion

We have previously reported that a) nNOS KO mice have severe deficits in contextual fear conditioning (Kelley et al., 2009), b) the nNOS inhibitor S-methyl-L-thiocitrulline impairs contextual fear conditioning in WT mice, and c) the NO donor molsidomine rescues the LTM deficits in nNOS KO mice (Kelley et al., 2010). NO has a major role in synaptic plasticity and the formation of late phase long-term potentiation (LTP). While phosphorylation of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) is required for LTM formation, evidence suggests that the NO pathway controls CREB-DNA binding and CRE-mediated gene expression (Riccio et al., 2006). The role of NO in epigenetic regulation of synaptic plasticity is suggested by two major findings. First, NO-dependent S-nitrosylation of HDAC2 dissociates the enzyme from CREB-regulated gene promoters, thereby increasing acetylation of histones at specific promoter regions and transcription of several genes, including c-fos, erg1, VGP and nNOS (Nott & Riccio, 2009; Nott et al., 2008). Second, the NO donor S-nitrosoglutathione inhibited HDAC2 activity in embryonic cortical neurons (Watson & Riccio, 2009), which causes an increase in histone acetylation. Therefore, we hypothesized that increased histone acetylation may rescue NO-dependent learning and memory deficits.

Recent studies suggest that regulation of chromatin structure is one of the essential molecular mechanisms that contribute to the formation of synaptic plasticity and LTM (Sweatt, 2009). One of the regulatory processes of chromatin structure is the acetylation and deacetylation of histone proteins. Histone acetyltransferases (HAT) acetylate conserved lysine amino acids on histone proteins by transferring an acetyl group from acetyl CoA to form ε-N-acetyl lysine. Acetylation brings in a negative charge, which neutralizes the positive charge on the histones and decreases the interaction of the N termini of histones with the negatively charged phosphate groups of DNA. As a result, the condensed chromatin is transformed into a more relaxed structure which is associated with greater levels of gene transcription (Jenuwein & Allis, 2001). HDAC are classes of enzymes that remove acetyl groups, increasing the positive charge of histone tails and the binding between histones and DNA. The increased DNA binding condenses DNA structure and prevents transcription.

Several HDAC inhibitors such as NaB, valproic acid, and trichostatin have been shown to increase acquisition and extinction of LTM (Bredy et al., 2007; Lattal et al., 2007; Levenson et al., 2004; Safford et al., 2012; Vecsey et al., 2007; Wood, Attner, Oliveira, Brindle & Abel, 2006; Yeh, Lin & Gean, 2004). NaB and valproic acid have relatively high affinity for Class I HDAC, including HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3 and HDAC8; their affinity for Class IIa and IIb HDAC is much lower (Kilgore et al., 2010).

The role of HDAC2 in memory formation is suggested by the following findings. First, overexpression and deficiency of HDAC2 in mice resulted in inhibition and facilitation of LTM, respectively (Guan et al., 2009). Second, NO targets S-nitrosylation of HDAC2, and the NO-donor S-nitrosoglutathione inhibits HDAC2 activity (Nott et al., 2008; Watson & Riccio, 2009), thus causing increased histone acetylation. Our studies indicated that the NO-donor molsidomine improved contextual fear conditioning in nNOS KO mice (Kelley et al., 2010) and in recent studies we found that systemic administration of molsidomine (20mg/kg) resulted in 25% increase in hippocampal H3 histone acetylation in nNOS KO but not WT mice (unpublished observations).

The first major finding of the current studies is that the HDAC inhibitor NaB improved contextual fear conditioning of nNOS KO mice but not of WT mice. The findings that a marked increase in NaB-induced H3 histone acetylation was observed in hippocampus and amygdala of nNOS KO mice, while a relatively small increase was observed in the hippocampus but not amygdala of WT mice (Fig. 1A), suggest that an increase in H3 histone acetylation reversed the learning deficits in nNOS KO mice. The finding that improvement in contextual fear conditioning occurred in NOS KO mice and not in WT mice may support the idea that HDAC inhibitors improve learning and memory deficits, while their effect on optimal associative learning and memory may be less conspicuous. For instance, Kilgore et al. (2010) found that class I HDAC inhibitors reversed memory deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease, but had no effect on WT mice. Likewise, NaB reversed deficits in contextual fear conditioning that result from inhibition of hippocampal DNA methylation in rats, but control rats remained unaffected (Miller, Campbell & Sweatt, 2008). On the other hand, the lack of effect of NaB on contextual fear conditioning in WT mice may be due to a “ceiling effect” we observed following conditioning by 0.75mA (Fig. 2B), and a near-ceiling effect observed following conditioning by 0.35mA (Fig. 2C). Hence, the effect of NaB on WT mice might have been detected if the freezing response in WT mice had been “weak” and lower in magnitude (30–40%). Important, however, are the observations that NaB a) improved acquisition of contextual fear conditioning in nNOS KO mice, and b) markedly increased the levels of total H3 histone acetylation in hippocampus and amygdala of nNOS KO mice (Fig. 1A).

Several studies support the role of H3 histone acetylation in acquisition/consolidation of LTM. First, hippocampal H3 but not H4 histone acetylation was associated with the memory enhancing effect of estradiol (Zhao, Fan & Frick, 2010). Second, contextual fear conditioning in rats resulted in selective increase in H3 but not H4 histone acetylation (Levenson et al., 2004; Miller et al., 2008). Third, activation of the NMDA-ERK pathway in the CA1 region of the hippocampus increased H3 histone acetylation, while H4 histone acetylation was not affected; H4 histone acetylation occurred with latent inhibition and decrease in fear conditioning (Levenson et al., 2004). In the same vein, extinction of cued fear conditioning was associated with increased H4 histone acetylation, and was facilitated by the HDAC inhibitor valproic acid (Bredy et al., 2007).

The second major finding of the current studies supports the role of H4 histone acetylation in extinction of cued fear conditioning in WT mice. We observed that NaB a) induced increase in H4 histone acetylation in hippocampus and amygdala of WT mice while its effect on H3 histone acetylation occurred only in the hippocampus (Fig. 1), and b) facilitated extinction of cued but not contextual fear conditioning (Fig. 4). Relatively low increase (~20%) in NaB-induced H3 histone acetylation was observed in the nucleus accumbens (Malvaez, Sanchis-Segura, Vo, Lattal & Wood, 2010), and an increase in NaB-induced H4 histone acetylation was several fold higher than H3 acetylation in the mouse striatum (Sanchis-Segura, Lopez-Atalaya & Barco, 2009).

We hypothesize that NaB-induced increase in H4 histone acetylation in the hippocampus and amygdala of WT mice is likely to lead to long-lasting effects on greater levels of gene transcription, which may afford long-term effect on extinction learning of cued memory. However, further studies are requited to investigate whether NaB has long-lasting effects on memory-related gene expression.

Nonetheless, the third major finding of the present studies is that NaB exerted long-lasting effect on extinction of cued memory in WT mice. Reports on the acceleration of extinction of fear conditioning by administration of HDAC inhibitors were based on either pre- (Bredy et al., 2007) or immediately post- (Lattal, Barrett & Wood, 2007) extinction training sessions. In our studies the acceleration in extinction of cued fear conditioning was observed 10–15 days after a single administration of NaB. Because our initial intent was to investigate the effect of the HDAC inhibitor on acquisition of fear conditioning, mice received NaB 60 min prior to fear conditioning training (day 1). Then, mice were tested for LTM 7 days posttraining. After an additional 3 days, daily extinction training began and lasted for 5 days. Significant differences between the saline and NaB pretreated groups emerged following the second day of cued extinction training (Fig. 4B).

The long-term effect of NaB was confirmed by the extinction of the renewal effect (Fig. 4C). When extinction is achieved in context B (Fig. 4B), reexposure to the original context A in the presence of a previously extinguished CS is expected to renew the freezing response (Fig. 4C). Indeed, extinction in context B resulted in 44±4% and 35±4% freezing in the saline and NaB groups, respectively (Fig. 4B); reexposure to context A resulted in 63±4% and 55±5% freezing in the saline and NaB groups, respectively (Fig. 4C). The differences between freezing in contexts B and A were significant for both groups (19–20%; p<0.05), suggesting that renewal occurred in both groups.

In the saline group, extinction of cued freezing in context A was not significant (from 63±4% to 55±6%), suggesting that renewal of cued memory in context A is more resistant to extinction than in context B (Fig. 4C). However, the reduction of cued freezing in the NaB group (from 55±6% to 39±6%) showed significant differences between the saline and the NaB groups on days 4 and 5 (p<0.05; Fig. 4C). NaB-induced acceleration of extinction of the renewal effect supports the hypothesis that the HDAC inhibitor facilitated behavior which is resistant to extinction. In addition, the results suggest that a single administration of NaB had long-term effect (beyond the 15 days of training-testing-extinction) on facilitating extinction of cued memory, in a manner independent of the context wherein the cue was presented.

The fourth finding of the current studies indicates that NaB accelerated the extinction of cued but not contextual fear conditioning (Fig. 4A, 4B). It is unclear why NaB accelerated the extinction of cued but not contextual fear conditioning. Recent studies suggest that NaB accelerated “weak” extinction but not “strong” extinction (Stafford et al., 2012). Comparison between context (Fig. 4A) and cue (Fig. 4B) extinction suggests that cued fear is extinguished more “difficult” than contextual fear. Hence, it appears that NaB facilitated the “weak” extinction process (cue) and it had no apparent effect on the “strong” or fast extinction process (context).

The fifth finding of the present study suggests that NaB accelerated extinction of cued memory of WT but not nNOS KO mice (Fig. 5B). To determine the effect of NaB on the consolidation of extinction learning, the HDAC inhibitor was administered to WT and nNOS KO mice immediately following the first extinction session (Fig. 5B). The finding that NaB facilitated cue extinction of WT mice in two different experimental designs further supports the premise that cue extinction of WT mice is sensitive to changes in histone acetylation. However, NaB did not influence the rate of cue extinction of nNOS KO mice.

Interestingly, results also showed significant difference between WT (saline) and nNOS KO (saline) mice in the rate of extinction; nNOS KO mice extinguished cued freezing faster than WT mice (Fig. 5B). The lack of effect of NaB on cue extinction of nNOS KO mice may support the hypothesis that NaB does not influence “strong” or fast extinction (Stafford et al., 2012). Thus, it appears that NO signaling is not required for extinction of cued memory as it is required for the acquisition of contextual memory. The reason for the fast cue extinction of nNOS KO mice is unclear but it may be due to the formation of relatively unstable LTM of cued fear. In previous studies we found that nNOS KO mice although acquired LTM of cocaine reward, the persistence of the conditioned response (approach behavior) to cocaine-associated context was relatively short-lived (Balda et al., 2006). Hence, the instability of LTM of nNOS KO mice may appear as fast extinction.

The significance of the results of extinction experiments lays in the findings that a) inhibition of HDAC prior to exposure to a fearful stimulus may accelerate extinction, long after consolidation of fear memory, b) extinction of cued memory is slower than that of contextual memory (Fig. 4B vs. 4A), and c) extinction of the renewal effect is more difficult to achieve than extinction of the initial cued memory (Fig. 4C vs. 4B). Therefore, NaB or other HDAC inhibitors may be particularly useful for the elimination of conditioned response which is resistant to extinction.

In summary, results of the present study suggest that increased H3 histone acetylation in the hippocampus and amygdala may rescue LTM memory impairment due to deficits in the NO signaling pathway. Increase in H4 histone acetylation in hippocampus and amygdala had long-term facilitatory effect on extinction of cued fear memory. Hence, a single administration of HDAC inhibitor may rescue NO-dependent cognitive deficits and afford long-term accelerating effect on extinction of cued fear memory of WT mice.

Highlights.

A single injection of NaB reversed contextual memory deficit in nNOS(−/−) mice

A single injection of NaB accelerated extinction of cued memory of wild-type mice

NaB had no effect on extinction of cued memory of nNOS(−/−) mice

NaB-induced H3 histone acetylation in nNOS(−/−) was greater than in wild-type mice

NaB-induced H4 histone acetylation was similar in nNOS(−/−) and wild-type mice

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant RO1DA026878 and R21DA029404 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahi J, Radulovic J, Spiess J. The role of hippocampal signaling cascades in consolidation of fear memory. Behavioural Brain Research. 2004;149:17–31. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(03)00207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balda M, Anderson KL, Itzhak Y. Adolescent and adult responsiveness to the inceptive value of cocaine reward in mice: role of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) gene. Neuropharmacology. 2006;51:341–349. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer EP, LeDoux JE, Nader K. Fear conditioning and LTP in the lateral amygdala are sensitive to the same stimulus contingencies. Nature Neuroscience. 2001;4:687–688. doi: 10.1038/89465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME. Context and behavioral processes in extinction. Learning & Memory. 2004;11:485–494. doi: 10.1101/lm.78804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, King DA. Contextual control of the extinction of conditioned fear: tests for the associative value of the context. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavioral Processes. 1983;9:248–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredy TW, Wu H, Crego C, Zellhoefer J, Sun YE, Barad M. Histone modifications around individual BDNF gene promoters in prefrontal cortex are associated with extinction of conditioned fear. Learning & Memory. 2007;4:268–276. doi: 10.1101/lm.500907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan JS, Haggarty SJ, Giacometti E, Dannenberg JH, Joseph N, Gao J, Nieland TJ, Zhou Y, Wang X, Mazitschek R, et al. HDAC2 negatively regulates memory formation and synaptic plasticity. Nature. 2009;459:55–60. doi: 10.1038/nature07925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang PL, Dawson TM, Bredt DS, Snyder SH, Fishman MC. Targeted disruption of the neuronal nitric oxide synthase gene. Cell. 1993;75:1273–1286. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90615-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Translating the histone code. Science. 2001;293:1074–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley JB, Anderson KL, Altman SL, Itzhak Y. Long-term memory of visually cued fear conditioning: roles of the neuronal nitric oxide synthase gene and cyclic AMP response element-binding protein. Neuroscience. 2011;174:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley JB, Anderson KL, Itzhak Y. Pharmacological modulation of nitric oxide signaling and contextual fear conditioning in mice. Psychopharmacology. 2010;210:65–74. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1817-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley JB, Balda MA, Anderson KL, Itzhak Y. Impairments in fear conditioning in mice lacking the nNOS gene. Learning & Memory. 2009;16:371–378. doi: 10.1101/lm.1329209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilgore M, Miller CA, Fass DM, Hennig KM, Haggarty SJ, Sweatt JD, Rumbaugh G. Inhibitors of class 1 histone deacetylases reverse contextual memory deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:870–880. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattal KM, Barrett RM, Wood MA. Systemic or intrahippocampal delivery of histone deacetylase inhibitors facilitates fear extinction. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2007;121:1125–1131. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.5.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson JM, O'Riordan KJ, Brown KD, Trinh MA, Molfese DL, Sweatt JD. Regulation of histone acetylation during memory formation in the hippocampus. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:40545–40559. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402229200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malvaez M, Sanchis-Segura C, Vo D, Lattal KM, Wood MA. Modulation of chromatin modification facilitates extinction of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S, Fanselow MS. Synaptic plasticity in the basolateral amygdala induced by hippocampal formation stimulation in vivo. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:7548–7564. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07548.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CA, Campbell SL, Sweatt JD. DNA methylation and histone acetylation work in concert to regulate memory formation and synaptic plasticity. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2008;89:599–603. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineka S, Oehlberg K. The relevance of recent developments in classical conditioning to understanding the etiology and maintenance of anxiety disorders. Acta Psychologica. 2008;127:567–580. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsey MS, Ota KT, Akingbade IF, Hong ES, Schafe GE. Epigenetic alterations are critical for fear memory consolidation and synaptic plasticity in the lateral amygdala. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nott A, Riccio A. Nitric oxide-mediated epigenetic mechanisms in developing neurons. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:725–730. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.5.7805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nott A, Watson PM, Robinson JD, Crepaldi L, Riccio A. S-Nitrosylation of histone deacetylase 2 induces chromatin remodelling in neurons. Nature. 2008;455:411–415. doi: 10.1038/nature07238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota KT, Pierre VJ, Ploski JE, Queen K, Schafe GE. The NO-cGMP-PKG signaling pathway regulates synaptic plasticity and fear memory consolidation in the lateral amygdala via activation of ERK/MAP kinase. Learning & Memory. 2008;15:792–805. doi: 10.1101/lm.1114808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips RG, LeDoux JE. Differential contribution of amygdala and hippocampus to cued and contextual fear conditioning. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1992;106:274–285. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resstel LB, Corrêa FM, Guimarães FS. The expression of contextual fear conditioning involves activation of an NMDA receptor-nitric oxide pathway in the medial prefrontal cortex. Cerebral Cortex. 2008;18:2027–2035. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccio A, Alvania RS, Lonze BE, Ramanan N, Kim T, Huang Y, Dawson TM, Snyder SH, Ginty DD. A nitric oxide signaling pathway controls CREB-mediated gene expression in neurons. Molecular Cell. 2006;21:283–294. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues SM, LeDoux JE, Sapolsky RM. The influence of stress hormones on fear circuitry. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2009;32:289–313. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogan MT, Stäubli UV, LeDoux JE. Fear conditioning induces associative long-term potentiation in the amygdala. Nature. 1997;390:604–607. doi: 10.1038/37601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchis-Segua C, Lopez-Atalaya JP, Barco A. Selective boosting of transcriptional and behavioral responses to drugs of abuse by histone deacetylase inhibition. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:2642–2654. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafe GE, Bauer EP, Rosis S, Farb CR, Rodrigues SM, LeDoux JE. Memory consolidation of Pavlovian fear conditioning requires nitric oxide signaling in the lateral amygdala. The European Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;22:201–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilatifard A. Chromatin modificatios by methylation and ubiquitination: implications in the regulation of gene expression. Annual Reviews in Biochemistry. 2006;75:243–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford JM, Raybuck JD, Raybinin AE, Lattal KM. Increased histone acetylation in hippocampus-infralimbic network enhances fear extinction. Biological Psychiatry. 2012 Jan 28; doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.12.012. 2012 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweatt JD. Experience-dependent epigenetic modification in the central nervous system. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;65:191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecsey CG, Hawk JD, Lattal KM, Stein JM, Fabian SA, Attner MA, Cabrera SM, McDonough CB, Brindle PK, Abel T, Wood MA. Histone deacetylase inhibitors enhance memory and synaptic plasticity via CREB:CBP-dependent transcriptional activation. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:6128–6140. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0296-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson PM, Riccio A. Nitric oxide and histone deacetylases: A new relationship between old molecules. Communicative & Integrative Biology. 2009;2:11–13. doi: 10.4161/cib.2.1.7301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MA, Attner MA, Oliveira AM, Brindle PK, Abel T. A transcription factor-binding domain of the coactivator CBP is essential for long-term memory and the expression of specific target genes. Learning & Memory. 2006;13:609–617. doi: 10.1101/lm.213906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh SH, Lin CH, Gean PW. Acetylation of nuclear factor-kappaB in rat amygdala improves long-term but not short-term retention of fear memory. Molecular Pharmacology. 2004;65:1286–1292. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.5.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Fan L, Frick KM. Epigenetic alterations regulate estradiol-induced enhancement of memory consolidation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:5605–5610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910578107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]