Abstract

Cadmium (Cd) is generally found in low concentrations in the environment due to its widespread and continual use, however, its concentration in some foods and cigarette smoke is high. Although evidence demonstrates that adult exposure to Cd causes changes in the immune system, there are limited reports of immunomodulatory effects of prenatal exposure to Cd. This study was designed to investigate the effects of prenatal exposure to Cd on the immune system of the offspring. Pregnant C57Bl/6 mice were exposed to an environmentally relevant dose of CdCl2 (10 ppm) and the effects on the immune system of the offspring were assessed at two time points following birth (2 and 7 weeks of age). Thymocyte and splenocyte phenotypes were analyzed by flow cytometry. Prenatal Cd exposure did not affect thymocyte populations at 2 and 7 weeks of age. In the spleen, the only significant effect on phenotype was a decrease in the number of macrophages in male offspring at both time points. Analysis of cytokine production by stimulated splenocytes demonstrated that prenatal Cd exposure decreased IL-2 and IL-4 production by cells from female offspring at 2 weeks of age. At 7 weeks of age, splenocyte IL-2 production was decreased in Cd-exposed males while IFN-γ production was decreased from both male and female Cd-exposed offspring. The ability of the Cd-exposed offspring to respond to immunization with a S. pneumoniae vaccine expressing T-dependent and T-independent streptococcal antigens showed marked increases in the levels of both T-dependent and T-independent serum antibody levels compared to control animals. CD4+FoxP3+CD25+ (nTreg) cell percentages were increased in the spleen and thymus in all Cd-exposed offspring except in the female spleen where a decrease was seen. CD8+CD223+ T cells were markedly decreased in the spleens in all offspring at 7 weeks of age. These findings suggest that even very low levels of Cd exposure during gestation can result in long term detrimental effects on the immune system of the offspring and these effects are to some extent sex-specific.

Keywords: cadmium, prenatal exposure, thymocytes, splenocytes, cytokines, antibody

INTRODUCTION

Cadmium (Cd) is a heavy metal that poses a hazard to human health due to its toxicity. There is sufficient evidence in humans to classify Cd and Cd compounds as carcinogens based on epidemiological studies demonstrating a link between Cd and lung, and possibly prostate cancers (IARC, 2004). Exposure to the heavy metal and its compounds primarily occurs in workplaces such as mining, smelting, processing, and battery manufacturing, whereas non-occupational exposures come from various foods, contaminated water, and tobacco smoke. Smokers generally have Cd blood levels 4-5 times those of non-smokers (Elinder et al., 1976).

Cd levels in the environment vary widely due to its ability to be transported through air, water, and soil. Humans normally absorb Cd into the body either by ingestion or inhalation (Lauwerys et al., 1986). The daily intake is estimated to be approximately 10-50 μg, but can reach levels of 200-1000 μg in highly contaminated areas (Nordberg, 2006). The average Cd intake from food in one study showed values of 38 - 300 μg/week (Olsson et al., 2002), while absorption from cigarette smoke is 1-3 μg/pack/day (Faroon et al., 2008). Cd levels in soils, particularly areas in which phosphate fertilizers have been applied, can range from 10 to 200 μg/g (Cook, 1995).

Humans do not have an effective Cd elimination pathway and as a result the biologic half-life of Cd in the human body is estimated to be 15-20 years (Jin et al., 1998). Excessive Cd accumulation in the body often results in diseases such as kidney failure, respiratory disease, neurological disorders, and occasionally death (Waalkes et al., 1992). Although pharmacokinetic studies have demonstrated that Cd does not readily reach the fetus, it accumulates in high concentrations in the placenta (Piasek et al., 2001). Teratological effects associated with Cd exposure reported for humans are limited; however, maternal exposure to environmental Cd, higher placental concentration (Loiacono et al., 1992), and/or fetal Cd exposure (Frery et al., 1993) has been associated with lower birth weights in humans. Moreover, the teratological effects of Cd in rodents have been extensively documented (Hovland et al., 1999; Scott et al., 2005; Minetti and Reale, 2006; Jacquillet et al., 2007).

There have been numerous studies on the immunomodulatory effects of Cd in adult humans and experimental animals; however, the findings remain controversial (reviewed by Descotes, 1992). This conflict amongst findings may be attributed to varying doses, route of administration, length of Cd exposure, and differences in the sensitivity of immune systems of different animal species. The thymus, the primary site of T-cell production, is a target organ of Cd-induced toxicity (Morselt et al., 1988). Thymocytes mature through a series of stages defined by expression of cell surface markers CD4 and CD8. The most immature thymocytes are CD4− CD8− double-negative (DN). This population gives rise to CD4+CD8+ double-positive (DP) cells, which then give rise to mature CD4+CD8− single-positive (SP) and CD4−CD8+ SP cells. The DN population can be further subdivided in mice based on the expression of surface markers CD25 and CD44: CD44+CD25−(DN1) cells differentiate into CD44+CD25+(DN2) cells, which then develop into CD44−CD25+(DN3) cells, which differentiate into the CD44−CD25−(DN4) population. Following Cd-treatment, damage occurs to the thymus as well as changes in the proliferation rate of thymocytes in adult rats (Morselt et al., 1988). In adult mice, Dong et al. (2001) observed a decrease in DP cells. Pathak and Khandelwal (2008) also demonstrated that Cd exposure decreased the DP population and increased the number of DN cells. In vivo studies exposing adult male rats to varying concentrations of Cd (0-100 ppm) demonstrated that lower doses of Cd inhibited humoral and cellular immune responses, while higher concentrations had a stimulatory effect (Lafuente et al., 2004). Analysis of oxidative stress and apoptosis showed that splenic cells appeared more susceptible than thymus cells to the adverse effects of Cd both in vitro (Pathak and Khandelwal, 2006a; Pathak and Khandelwal, 2006b) and in vivo (Pathak and Khandelwal, 2007).

Despite numerous studies demonstrating the effects of Cd on the adult immune system (Mackova et al., 1996b; Liu et al., 1999a; Lafuente et al., 2004), there have been limited reports on the effect of Cd exposure during gestation on the immune system of the offspring. We have previously shown that prenatal exposure to Cd affects thymocyte development of newborn (<12 h old) offspring (Hanson et al., 2010). The study reported herein was designed to investigate the continued effects of prenatal exposure to Cd on the immune system of the offspring. Pregnant mice were exposed to an environmentally relevant dose of CdCl2 (10 ppm) and the effects on the immune system of the offspring were assessed at two time points following birth [2 and 7 weeks of age] to evaluate the effects in relation to developmental stage. There were numerous changes in the level of spleen cell cytokine production and serum anti-streptococcal antibody responses in the animals exposed to Cd prenatally as compared to the controls at 7 weeks of age. The relative percentage of CD4+FoxP3+CD25+ (nTreg) and CD8+CD223+ T cells was also markedly different between the two groups at 7 weeks of age.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Breeding and Cd Exposure Methodology

C57Bl/6 mice at 8-10 weeks of age were obtained from Hilltop Lab Animals, Inc. (Scottsdale, PA). The C57Bl/6 strain of mouse was used for these experiments due to its reported teratogenic susceptibility to Cd exposure (Hovland et al., 1999). Mice were allowed to acclimate on site for at least one week. Two females were placed in a cage with one male for 72 hours to maximize pregnancy rate. Females were inspected for a vaginal plug and if present, this day was declared as gestational day 0. Ten dams were used as controls, having free access to deionized distilled water (ddH20), while ten additional dams had free access to 10 ppm of CdCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO) dissolved inddH20. The dose of 10 ppm was chosen because it is the greatest concentration that will elicit immunomodulatory effects in adult rodents without causing systemic effects (Lafuente et al., 2003). In addition, 10 ppm is a relatively low and environmentally realistic concentration (Thijssen et al., 2007). Cd administration was stopped at birth. Following parturition, Cd levels in the kidneys of dams were measured as previously described (Hanson et al., 2009) to ensure consistent Cd dosing among dams. No significant differences in Cd burden were seen between the dams (data not shown). At 2 and 7 weeks of age, 3 offspring (at least 1 male and 1 female) selected from each of the litters were euthanized and thymi and spleens were removed. Mice born from a different set of dams were euthanized at 7 weeks of age to ensure adequate sample size. The 2 weeks of age time point was chosen to determine if any longer term effects of prenatal exposure to Cd were evident early in life and 7 weeks of age was chosen to assess the effects of prenatal Cd exposure at the mouse adult stage. The 7 week time point would approximate a younger post-pubescent human which should have a fully developed robust immune response. All offspring were weaned at 3 weeks of age and the dams were euthanized. All animal procedures were approved by the WVU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Tissue Isolation and Cell Preparation

Thymi and spleens were harvested from euthanized mice and single cell suspensions prepared. The cell preparations from each mouse were analyzed individually. Red blood cells were lysed using an ammonium chloride lysis buffer. Viable cells were enumerated using trypan blue and a hemacytometer.

Cell staining and flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions of thymocytes and splenocytes were prepared as described above. Thymocytes were stained using combinations of the following fluorochrome directly conjugated antibodies: anti-CD45-biotin (clone 30-F11; eBioscience; San Diego, CA), streptavidin-Pacific Blue (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA), anti-CD44-PE-Cy5 (clone IM7; eBioscience), anti-CD25-PE-Cy7 (clone PC61.5; eBioscience), anti-CD4-FITC (clone RM4-5; BD Biosciences Pharmingen; San Jose, CA), and anti-CD8-PE (clone 53-6.7; BD Biosciences Pharmingen). SP and DP cell subpopulations were identified using anti-CD4 and anti-CD8. To identify the different DN subpopulations, CD44 and CD25 expression were detected on the CD4−CD8− population. Splenocytes were stained using combinations of the following directly conjugated Abs: anti-CD4-FITC (BD Biosciences Pharmingen), anti-CD8-PE (BD Biosciences Pharmingen), anti-F4/80-APC-Alexa Fluor 750 (clone BM8; eBioscience), anti-Gr1-Alexa Fluor 700 (clone RB6-8C5; eBioscience), and anti-B220-PE-Cy5 (clone RA3-6B2; BD Biosciences Pharmingen). Cells (1 × 106) were washed with PBSAz (phosphate buffered saline containing 2% FBS and 0.2% sodium azide), incubated with whole rat and mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for 30 min on ice to block Fc recptors, followed by a PBSAz wash. The cells were incubated for 30 min on ice with fluorochrome labeled antibodies, washed several times with PBSAz and fixed overnight at 4°C with 0.4% paraformaldehyde. The paraformaldehyde was removed by washing and cells resuspended in PBSAz. Data were acquired using a FACSAria and analyzed employing Diva 6.1 software (BD Biosciences Pharmingen) and FCA Express software (De Nova Software). A total of 10,000 events were collected for each sample.

To detect the CD8+CD223+T cells in spleen and thymus, a combination of fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against CD8 (FITC), CD28 (APC, clone 37.51) and CD223 (PE, clone eBioC9B7W; CD223 is also called LAG-3; eBioscence) was used as above.

CD4+ nTreg cells expressing the transcription factor FoxP3 were detected using antibodies (eBioscience) against membrane-associated CD4-FITC, and CD25-APC (clone PC61.5), in addition to intracellular FoxP3-PE (clone FJK-16a). Splenocyte and thymocyte surface staining with anti-CD4 and anti-CD25 performed as above followed by fixation/permeabilization for 30 min, washed and stained for 30 min with anti-FoxP3-PE antibody or the rat IgG2a isotype control-PE. Cells were washed twice, resuspended in PBSAz and analyzed on a flow cytometer.

Cytokine production

The production of cytokines by splenocytes at 2 and 7 weeks of age was measured using the Mouse TH1/TH2 Ready-SET-Go! ELISA set (eBioscience). Briefly, 1 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI media (Mediatech Cellgro; Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% FBS were seeded in 48-well plates and stimulated with anti-CD3 (10 g/ml; clone 17A2; eBioscience) and anti-CD28 (10 g/ml; clone; 37.51; eBioscience). The culture supernatant was collected 24 h after the stimulation for the assessment of IL (interleukin)-2, and 72 h after the stimulation for the assessment of IL-4, IL-10, IL-12p70, TNF-α, Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 (MCP-1), IL-6 and IFN-γ. The concentrations of the cytokines were assessed per manufacturer’s protocol. The limit of detection for the cytokines shown was IL-2 (2 pg/ml), IFN-γ, (15 pg/ml), IL-10 (30 pg/ml), and IL-4 (4 pg/ml).

Preparation of S. pneumonia vaccine and immunization

Functional analysis of the immune system was performed by immunizing the offspring with a heat-killed vaccine of Streptococcus pneumoniae strain R36A antigen. S. pneumoniae strain R36A is an avirulent, nonencapsulated strain commonly used as a source of antigen and the kinetics of the serum antibody response and the predominant types of antibody isotypes to phosphorylcholine (PC) and pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA) have been well characterized (Wu et al., 1999; Wu et al., 2000).

The vaccine was prepared as described by Salazar et al. (Salazar et al., 2005). Briefly, S. pneumoniae strain R36A, was grown to mid-log phase in Todd-Hewitt broth (Difco) supplemented with 0.05% yeast extract (Difco) at 37 C in the presence of 10% CO2 to an OD600 of ~0.4. They were heat killed at 600C for 2 hr, washed twice and resuspended in saline at 2×109 CFU/ml. Sterility and CFU were confirmed by culture on blood agar. Heat-killed stock was stored at −80°C in 1 ml aliquots. Mice were immunized intraperitoneally with 2×108 CFU in 100 μl and blood was collected 10 days following immunization.

Preparation of PspA

Plasmid UAB055, which contains the truncated PspA gene attached to a 6-His tag, was a gift of Dr. Susan Hollingshead (Department of Microbiology, UAB, Birmingham, AL). The plasmid was transformed into BL21 (DE3) pLysS (EMD Biosciences). A selected transformant colony was grown in Luria broth (Difco) supplemented with 100 g/ml ampicillin (Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO) to OD600 of 0.5, induced with 1 mM IPTG for 4 hr and harvested. His-tagged PspA protein was purified from periplasmic extract using BugBuster HisBind purification kit (EMD Biosciences), dialyzed extensively against PBS, adjusted to 0.25 mg/ml and stored at 4°C.

Antibody quantitation

Blood samples were collected from immunized mice and sera obtained by standardized methods and stored at −20°C until assayed. For ELISA assays, Immulon 2 plates (ThermoLabsystems, Franklin, MA) were coated overnight at 4 °C with 2 μg/ml PC-BSA or 5 μg/ml PspA. Plates were washed, blocked with 1% BSA in PBS at 37 °C for 1 hr. Plates were washed with PBS and 100 μl/well serum diluted in PBS was added starting at 1/400 for the PC-BSA and 1/50 for PspA and twofold dilutions thereafter, and allowed to bind overnight at 40C. Plates were then washed and incubated with AP conjugated antibodies (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL) for 3 hour at 37 °C. After washing, 100 μl/well phosphatase substrate (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO) dissolved in diethanolamine buffer, pH 9.8 was added. Absorbance values were read at 405nm (A405) at timed intervals using a Quant spectrophotometer (Bio-Tek instruments, Winooski, VT) using KCJunior software (Bio-Tek instruments, Winooski, VT). To determine the titer, a standard pooled sera was diluted and plated on each ELISA plate. The titer for each sample was determined by comparison to the standard sera when the A405 for the standard was 0.4 at a 1:3200 dilution to measure all anti-PC antibody isotypes and 0.2 for anti-PspA IgM and IgG isotypes. These dilutions were chosen because they were in the linear part of the curve for the respective isotypes. In some instances, the anti-PspA IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b titers were determined at an A405 of 0.2 after 120 min of incubation.

Statistical Analyses

Results are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. Data expressed in percent of total or percent of control for cell populations were analyzed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney (Wilcoxon) test. T-test was used to analyze cytokine concentrations, PspA and PC titers, between Cd-exposed and control offspring. For Figures 1-6, each bar represents a mean of 5-8 offspring/sex/treatment group/age group. An alpha value of p≤0.05 was considered significant. Experiments represented in Figures 1-3 were repeated at least three times and experiments represented in Figures 4-6 were repeated at least 2 times.

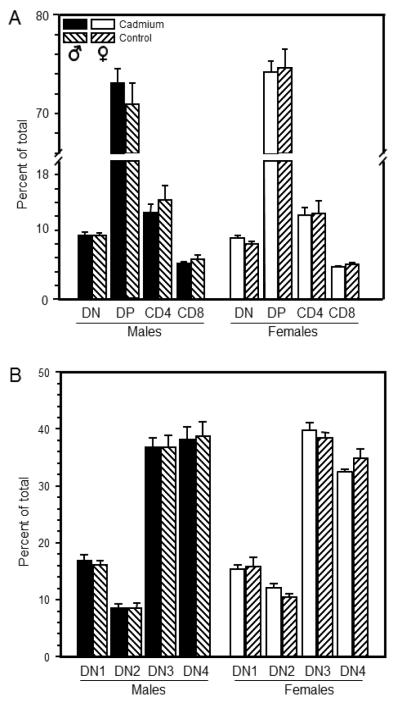

Figure 1.

Prenatal Cd exposure failed to induce lasting changes to the thymocyte phenotype of 7 week-old offspring. Thymocytes were isolated from mice that were exposed to 10 ppm Cd and analyzed by flow cytometry analysis as described in the Materials and Methods. Each bar represents the mean SE. Data are representative of 3 experiments where N=4 in each group. (A) Thymocyte phenotype was determined based on CD4 and CD8 cell surface expression. (B) DN subpopulation phenotype was determined based on CD44 and CD25 cell surface expression.

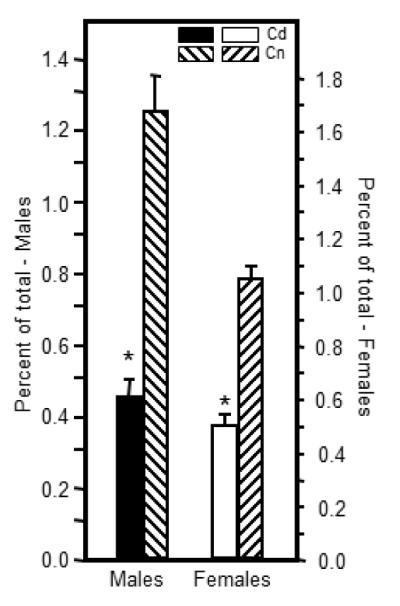

Figure 6.

Prenatal Cd exposure altered the relative percentage of CD8+CD223+ cell populations in the spleens of 7 week-old offspring. Flow cytometric analysis was performed by staining splenocytes or thymocytes with anti-CD8, anti-CD28 and anti-CD223. Each bar represents the mean SE. Data are representative of 2 experiments where N=5 offspring/sex/treatment group/age group. *p<0.05

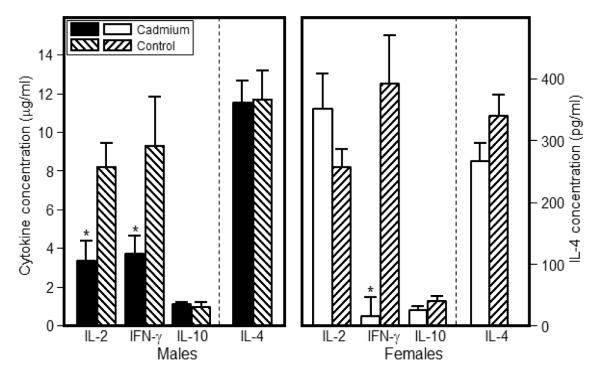

Figure 3.

Cytokine production by spleen cells from 7 week-old offspring was markedly altered by prenatal Cd exposure. Spleen cells were isolated and stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24h (IL-2) or 72h (IFN-, IL-10 and IL-4). Supernatants were analyzed for cytokine expression by ELISA kits. Limit of detection: IL-2 (2 pg/ml), IFN-γ, (15 pg/ml), IL-10 (30 pg/ml), IL-4 (4 pg/ml). Each bar represents the mean SE. Data are representative of 3 experiments where N=5-8 offspring/sex/treatment group. *p<0.05

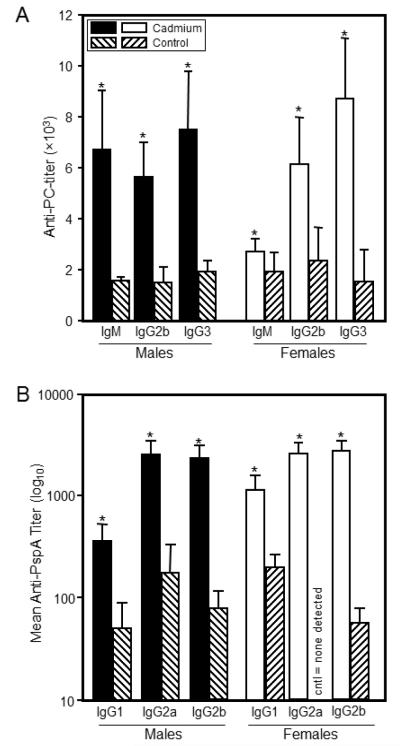

Figure 4.

T-independent and T-dependent serum antibody production at 7 weeks of age was markedly altered by prenatal exposure to Cd. Seven week-old mice that were exposed to 10 ppm Cd in utero were immunized with S. pneumoniae heat-killed vaccine. Sera were collected 10 days after immunization for anti-PC antibody (Figure 4A) and anti-PspA antibody (Figure 4B). Antibody levels were determined by ELISA as described in the Materials and Methods. Each bar represents the mean SE. Data are representative of 2 experiments where N=5 offspring/sex/treatment group/age group. *p<0.05

RESULTS

Prenatal Cd exposure does not change the relative percentages of thymocyte or splenocyte phenotypes in 2 and 7 week old offspring

Thymocyte phenotype of representative offspring from each litter was measured by cell surface marker expression using flow cytometry. Total thymocyte number was not significantly different between Cd-exposed and control offspring at 2 weeks of age (25.9±3.4 × 107 vs. 23.0±3.0 × 107, respectively) or at 7 weeks of age (25.4±2.2 × 107 vs. 21.2±1.8 × 107, respectively). No phenotypic changes in the thymocyte populations were detectable at 2 weeks of age (Figure S1, Panel A and B) or at 7 weeks of age for either sex (Figure 1, panel A and B).

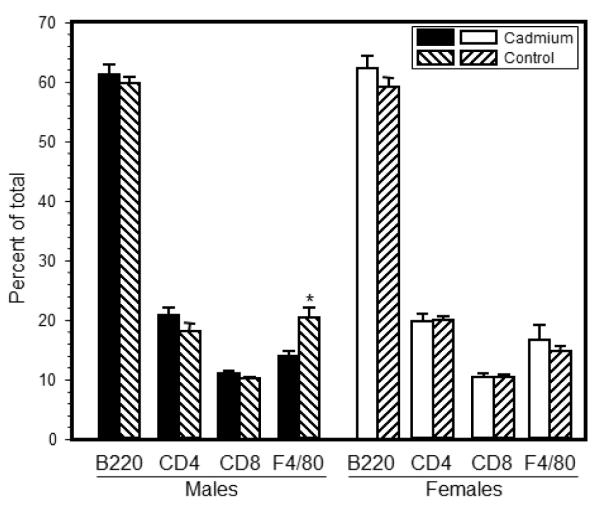

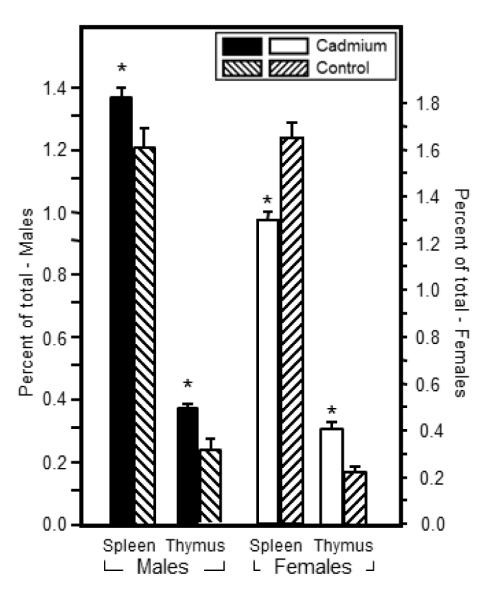

Splenocyte phenotype of representative offspring from each litter was determined by flow cytometry using cell markers specific for CD4 and CD8 T cells, B cells, macrophages, and granulocytes. Total splenocyte number was not significantly different between Cd-exposed and control offspring (1.1±0.8 × 108 vs. 1.0±0.93 × 108, respectively). At 2 weeks of age, neither sex showed any differences in the percentage of these cell types (Figure S2). The only cell type that showed a significant difference between the Cd-exposed offspring and control animals was reproducible decrease in macrophages in males at 7 weeks of age (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Prenatal Cd exposure induced minimal changes to the splenocyte phenotype of 7 week-old offspring. Spleen cells were isolated from mice that were exposed to 10 ppm Cd and analyzed by flow cytometry analysis as described in the Materials and Methods. Flow cytometric analysis was performed by staining splenocytes with anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-B220 (B cells), anti-F4/80 (macrophages), and anti-Gr-1 (granulocytes). Each bar represents the mean SE. Data are representative of 3 experiments where N=5-8 offspring/sex/treatment group/age group. *p<0.01

Prenatal Cd exposure caused marked changes in spleen cells ex vivo cytokine production at 2 and 7 weeks of age

In order to determine the effects of prenatal Cd exposure on the immune response of offspring at 2 and 7 weeks of age, production of IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-12p70, TNF-α, MCP-1, IL-6 and IFN-γ by splenic T cells was measured following stimulation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28. At 2 weeks of age, Cd-exposed female offspring produced significantly less IL-2 than control female offspring (Cd-treated, 2.31±0.77 g/ml vs. control, 7.40±1.41 g/ml (p<0.01; Figure S3). IL-4 production was also significantly decreased in Cd-exposed female offspring compared to control female offspring (Cd-treated, 202.42±7.15 pg/ml vs. control, 299.76±17.86 pg/ml; p<0.05; Figure S3). In addition, IFN-γ was markedly lower in Cd-exposed female offspring (p<0.06) (Figure S3). Cd-exposed male offspring did not demonstrate any statistically significant difference in cytokine production at 2 weeks of age. There were no significant differences in the levels of IL-12p70, TNF-α, MCP-1, and IL-6 between the Cd-exposed offspring and the controls at 2 or 7 weeks of age (data not shown).

At 7 weeks of age, IL-2 production rebounded in Cd-exposed females compared to control females (Cd-exposed, 11.4±1.9 μg/ml vs. control, 8.21±1.22 μg/ml; p<0.05) while males showed significant decreases in IL-2 at this age (Cd-treated, 3.5±0.9 μg/ml vs. control, 8.1±1.9 μg/ml; Figure 3). IFN-γ was significantly decreased in both Cd-exposed females (Cd-exposed, 0.47±0.10 μg/ml vs. control, 12.52±2.48 μg/ml) and males (Cd-exposed, 3.69±0.98 μg/ml vs. control, 9.29±2.54 μg/ml) compared to control animals (Figure 3). There were no differences in IL-10 or IL-4 production in either Cd-exposed males or females at 7 weeks of age. In summary, the data suggest that in Cd-exposed female offspring the levels of cytokines produced by Th1 cells (IFN-γ producing) were compromised, while Th2 cells (IL-10 and IL-4 producing) did not appear to be affected. In the male offspring, at 7 weeks of age, a similar bias against Th1 cell derived cytokines was evident.

Prenatal Cd exposure increased the specific anti-PC and anti-PspA antibody response at 7 weeks of age

An assessment of the functionality of the immune system was performed by measuring the T-independent and T-dependent antibody responses after vaccination with P. pneumoniae vaccine. The T-independent response, anti-PC, provides a functional assessment of the ability of the B cell to be stimulated by antigen and differentiate into IgM producing plasma cells. In addition, type II T-independent antigens, such as PC, can induce switching via dendritic cells to produce IgG antibodies (Colino et al., 2002). The level of anti-PC antibody of all isotypes was significantly higher in offspring prenatally exposed to Cd (Figure 4A and Table 1). For the males, the antibody titers were approximately three-fold higher in the Cd-exposed animals over the control male offspring (Figure 4A and Table 1). Similar or higher fold differences were also seen in the female offspring except for the IgM, which showed only a small but significant increase over controls (Figure 4A and Table 1).

Table 1.

Serum anti-PC and anti-PspA titers in 7 week-old offspring 10 days after immunization with S. pneumoniae heat-killed vaccine

| Antibody | Sex | Cd-treated | Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-PC | |||

| IgM | Male | 6720±2322* | 1560±163 |

| IgG2b | Male | 5660±1349* | 1500±625 |

| IgG3 | Male | 7520±2298* | 1940±430 |

| IgM | Female | 2720±495* | 1940±750 |

| IgG2b | Female | 6160±1824* | 2360±1306 |

| IgG3 | Female | 8720±2369* | 1540±1261 |

| Anti-PspA | |||

| IgM | Male | 1010±599 | 595±100 |

| IgG1 | Male | 360±163* | 50±40 |

| IgG2a | Male | 2540±936* | 175±159 |

| IgG2b | Male | 2360±724* | 77.5±38 |

| IgM | Female | 590±139 | 690±120 |

| IgG1 | Female | 560±311* | 55±26 |

| IgG2a | Female | 1680±605* | ND |

| IgG2b | Female | 1800±594* | 10±5.5 |

p<0.05;

ND, none detected

The T-dependent response requires the cooperative participation of antigen-presenting cells, T-helper cells and B cells. Thus, this measurement provides a very comprehensive picture of the ability of the animal to respond to an antigenic challenge. The T-dependent antigen PspA induced a robust IgG response in both Cd-exposed and control offspring, with the exception of the female controls, which produced no detectable anti-PspA IgG2a antibody (Figure 4B and Table 1). The anti-PspA IgG response was always an order of magnitude higher in those animals exposed to Cd prenatally. IgM titers were also measured (Table 1) and showed no significant difference between Cd-exposed and control animal titers for either sex.

Prenatal Cd exposure altered the percentages of natural T regulatory cell populations at 7 weeks of age

Changes in nTreg cell levels in the Cd-exposed offspring could provide a possible explanation for the increase in anti-S. pneumoniae antibodies. Therefore, nTreg cells were measured in the spleen as well as the thymus in both males and females. These cells were enumerated by flow cytometric analysis after staining with nTreg-specific markers in addition to the traditional CD4 markers, the CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ phenotype. In the male offspring, the percentages of nTreg cells were statistically higher in the Cd-exposed offspring in both the spleen and thymus (Figure 5). In the female offspring, the nTreg cells in Cd-exposed animals were statistically lower than the comparable controls in the spleen (Figure 5). However, the opposite result occurred in the thymus where Cd-exposed offspring showed statistically higher percentages of nTreg cells (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Prenatal Cd exposure altered the relative percentage of a population of CD4+ natural T regulatory cells (nTreg) in the spleens and thymi of 7 week-old offspring. Single cell suspensions were prepared for flow cytometry analysis by standard methods. Aliquots of unstimulated cells were stained with anti-CD4, anti-CD25 and anti-FoxP3 to quantify nTreg cells as described in the Materials and Methods. Each bar represents the mean SE. Data are representative of 2 experiments where N=5 offspring/sex/treatment group/age group. *p<0.05

Prenatal Cd exposure altered the percentages of CD223+ (LAG-3) CD8+ cell populations

A CD8+CD223+ T cell has been identified that shows increased expression on antigen-stimulated CD8+ T cells (Blackburn et al., 2009) and on CD8+ cells that demonstrate immune ‘exhaustion’ as a result of chronic virus infection (Blackburn et al., 2009) and loss of self-tolerance (Grosso et al., 2007). In the spleen, CD8+CD223+ T cells were approximately three-fold lower in the Cd-exposed male offspring and approximately two-fold lower in the female Cd-exposed offspring as compared to their sex-matched control counterparts (Figure 6). These cells were harvested from non-immunized animals and not experimentally stimulated with antigen. The numbers of these CD8+CD223+ T cells were not significantly different in the thymus between Cd-exposed and controls of either sex (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Immunotoxicity after Cd exposure in adult animals is well documented; however, reports concerning the effect of Cd exposure during gestation on the immune system are limited. We have previously demonstrated that prenatal Cd exposure alters thymocyte development in offspring at postnatal day 0 (PND0) (Hanson et al., 2010). Soukupova et al. (1991) reported that the proliferative responses of spleen cells to mitogens was increased at 8 weeks of age and while the oxidative burst activity of peritoneal macrophages was increased at 4 weeks of age, it was reduced by 8 weeks of age. Soukupova et al. (1991) also showed that the delayed type hypersensitivity to sheep red blood cells after immunization was decreased in prenatal Cd-exposed offspring at 8 weeks of age. Due to organogenesis of the immune system occurring primarily at the prenatal, and to a lesser extent, at the early postnatal stage, the perinatal period is not only more sensitive to deleterious effects of immunotoxicants, but alterations in the immune system can result in persistent effects (Holladay and Smialowicz, 2000). Exposure to toxic agents such as halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons (HAHs), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), hormonal substances, and heavy metals during the developmental period can result in a range of functional defects in adulthood, including suppression of the immune system (Blaylock et al., 1992; Keil et al., 2008), hypersensitivity (Miller et al., 1998), and autoimmune disease (Snyder et al., 2000; Mustafa et al., 2008). In vitro studies have demonstrated that Cd causes oxidative stress and apoptosis in adult mouse T- and B-cells (Pathak and Khandelwal, 2006b; Pathak and Khandelwal, 2006a), as well as macrophages (Kim and Sharma, 2006). The thymus is an important primary lymphoid organ where successive stages of cell development and selection produce functionally competent T cells from immature precursor cells. Several in vivo studies demonstrated that adult exposure to a wide range of Cd doses is able to cause significant weight decrease or atrophy of the thymus in mice (Borgman et al., 1986; Mackova et al., 1996a; Liu et al., 1999b). In addition, in vitro studies have demonstrated that exposure to Cd results in apoptosis and phenotypic changes in thymocytes from adult mice (Dong et al., 2001; Pathak and Khandelwal, 2008). The present analysis of offspring thymocyte phenotype following prenatal Cd exposure demonstrates no significant changes in the DN population. Examination of the four DN subpopulations after prenatal Cd exposure at both 2 and 7 weeks of age also showed no significant persistent phenotypic changes. We have previously shown a link between prenatal Cd exposure and dysregulation of the sonic hedgehog (Shh) and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways in the thymus at PND0 (Hanson et al., 2010). Both of these pathways are needed for differentiation of DN1 cells to DN2 cells, and while a continued perturbation of the phenotypes at 2 and 7 weeks of age was expected, we do not believe that the lack of phenotypic differences necessarily negates a probable role of the Shh and Wnt/β-catenin pathways at later time periods. Studies using Shh or Wnt/β-catenin knockout mice cannot be referenced to verify this since embryonic Shh-/- and Wnt/β-catenin-/- is lethal and only conditional KO studies have been conducted on Shh and Wnt/β-catenin postnatally.

In vitro and in vivo studies in adult mice have shown that splenocytes are more sensitive to Cd exposure than are thymocytes (Pathak and Khandelwal, 2006b; Pathak and Khandelwal, 2006a; Pathak and Khandelwal, 2007). Although we did not observe a significant decrease in the total number of splenocytes in prenatally Cd-exposed offspring, an analysis of splenocyte phenotype demonstrated that the macrophage population was decreased in Cd-exposed offspring. More strikingly, this effect was only present in male offspring. In vivo studies by others indicate that chronic Cd exposure alters the redox balance in adult male mice, inducing changes in lipid metabolism in macrophages, ultimately leading to apoptosis (Ramirez and Gimenez, 2002). In addition to being antigen presenting cells and phagocytes, macrophages can recognize tumor cells and induce cell death by releasing cytotoxic factors such as reactive oxygen and/or nitrogen intermediates, as well as cytokines; thus, the decrease in macrophage number in prenatal Cd-exposed male offspring might indicate an increased susceptibility of males to tumor incidence. Further studies are warranted to understand the mechanism of this cell type-, sex-specific effect.

Since cytokines influence or control most immune responses, cytokine production by spleen cells after T cell-specific stimulation was determined. In vitro studies have suggested that Th1 type cytokines (IL-2, IFN-γ) are depressed to a higher degree than Th2 type cytokines (IL-10, IL-4) following Cd exposure (Krocova et al., 2000; Hemdan et al., 2006; Pathak and Khandelwal, 2008). Studies demonstrating that a decrease in Shh signaling in peripheral CD4+ T cells down-regulates the synthesis of IL-2 and IFN-γ (Stewart et al., 2002) and that prenatal Cd exposure decreases Shh signaling in the thymus of offspring at PND0 (Hanson et al., 2010), led to the hypothesis that Th1 cells in the spleen would be more sensitive to prenatal Cd exposure than Th2 cells. In the present study, analysis at 2 weeks of age demonstrated that while cytokine production (IL-2 and IL-4) was only decreased in females, by 7 weeks of age a dramatic decrease in the ability of splenocytes from Cd-exposed male offspring to produce cytokines characteristic of the Th1 type was evident. Furthermore, a decrease in IFN-γ secretion by spleen cells from female offspring was also evident.

Mouse studies evaluating sex differences following Cd exposure are sparse. In humans, although no studies have been designed to investigate sex differences directly, related studies have shown that Cd-associated health effects are more frequent among women than men (Vahter et al., 2002). This may be due to a higher Cd body burden in women, reflected as higher Cd levels in blood, urine, and kidney cortex (Vahter et al., 2007). The main reason for the higher body burden in women is increased intestinal absorption of dietary Cd at low iron stores (Akesson et al., 2002; Kippler et al., 2007). Cd and iron compete with one another for transport into the mucosa cell via the divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT-1). When a woman is pregnant, enterocytes have an increased divalent metal transporter-1 density at the apical surface to increase absorption of micronutrients, thus Cd absorption is increased during pregnancy (Akesson et al., 2002; Vahter et al., 2007). It has been reported that 90% of patients with Itai-Itai disease, the most severe form of chronic Cd intoxication in humans, were postmenopausal women (Jarup et al., 1998). This is due to Cd’s ability to disrupt calcium homeostasis caused by estrogen depletion during menopause or following ovariectomy (Jarup et al., 1998). Another reason for sex-differences in susceptibility to Cd-induced toxicity may be attributed to Cd having estrogenic effects (Garcia-Morales et al., 1994; Stoica et al., 2000; Sogawa et al., 2001; Choe et al., 2003; Johnson et al., 2003). Following in utero exposure to Cd, female offspring experienced an earlier onset of puberty and an increase in the epithelial area and the number of terminal end buds in the mammary gland (Johnson et al., 2003). In addition, in vivo studies using adult female rats suggest that females may be at a greater risk than males for Cd-induced immunomodulation due to interactions between estrogen and Cd (Pillet et al., 2006). Pathak and Khandelwal (2008) demonstrated that IFN-γ is inhibited at a lower Cd concentration than IL-2 in adult male mice, so if female offspring have a higher body burden or are more sensitive to prenatal Cd exposure, then a higher dose of Cd may be necessary to elicit a decrease in IL-2 in male offspring, thus explaining the lack of effect on IL-2 production, but decreased IFN-γ production in male offspring in the present study.

Specific anti-streptococcal antibodies were uniformly greater in the Cd-exposed offspring. In most cases, the increase was markedly higher and covered all of the IgG subtypes. The anti-PC IgM levels were only slightly (but significantly) higher in the females. These increased antibody levels (Figure 5) appear to be at odds with the increased nTreg population in the spleen and thymus in the male offspring. Further, the decrease in the splenic nTreg cells in the female offspring does not seem to be of sufficient magnitude to cause the marked increases in antibody levels (Figure 5). However, it is important to note that the Treg assays were performed on the spleen and thymus cell populations whereas the bone is a major source of plasma cells that produce serum antibody (Winter et al., 2010). Thus, one explanation for these data is that the serum antibody levels are a product of plasma cells resident in the bone marrow and speculatively, if the number of nTreg cells in the bone marrow was lower in Cd-treated offspring, then the effect would be an increase in serum antibody levels.

A reduction of 64% and 57% in males and females over control levels of splenic CD8+CD223+ cells (Figure 6) due to prenatal xenobiotic exposure has not been previously reported to our knowledge. An increase in CD8+CD223+ cells has been described in the literature as being directly correlated with an increase in autoimmune disorders (Grosso et al., 2007) and T cell exhaustion (Shin and Wherry, 2007; Blackburn et al., 2009). At first blush, our measured decrease in CD8+CD223+ cells may indicate a decreased susceptibility of the Cd-exposed animals to autoimmune disorders as described by (Grosso et al., 2007), however, prenatal Cd-exposure caused a dramatic increase in anti-streptococcal antibodies which might be indicative of an actual increase in autoimmune susceptibility. Shin and Wherry (2007) reported that IL-2 production drops with T cell exhaustion which matches our results in the males, however, Blackburn et al. (Blackburn et al., 2009) showed increased expression of CD8+CD223+ with T cell exhaustion due to chronic virus infection. This is a contradiction to our results. Without experiments specifically designed to determine whether these changes in CD8+CD223+ populations have functional consequences, it would be overly speculative to place a meaning on the changes noted in the CD8+CD223+ cells. However, reductions in the number of cells expressing this marker in the Cd-exposed offspring that exceed ~60% on un-manipulated cells in a population of splenic CD8+ T cells previously shown to be active in autoimmunity and tumor surveillance (Grosso et al., 2007) as well as anti-viral defenses (Blackburn et al., 2009) is of concern. These results also serve to highlight that animals exposed prenatally to a xenobiotic often show a phenotype that differs from the phenotype produced by the same xenobiotic administered during adult life.

The immunomodulatory effects of prenatal Cd exposure observed in this study may provide insight as to why children of women who smoke during pregnancy have an increased risk for developing cancer later in life. Several studies have indicated that smoking while pregnant increases the risk of certain types of childhood cancers, such as leukemia, lymphoma, and central nervous system tumors, in the prenatally exposed offspring (Filippini et al., 1994; Filippini et al., 2000; Schuz et al., 2001; Brooks et al., 2004). In the U.S., more than a million newborns are exposed to cigarette smoke during gestation (DHHS, 2000). The amount of Cd absorbed from smoking a pack of cigarettes is about 1-3 μg per day (Faroon et al., 2008). The dams in our study ingested an estimated 15 μg of Cd per day, based upon the average daily water intake determined by Bachmanov et al. (2002). Considering that ≤10% of Cd ingested is absorbed (Faroon et al., 2008), the body burden of these dams would be ≤1.5 μg per day. Therefore, without regard to differences in body surface area and route of exposure, the concentration of Cd being ingested by mice in the present experiment is equivalent to the concentration of Cd that would be inhaled from smoking 1 pack of cigarettes per day. A study in which pregnant mice were exposed to a low concentration of mainstream cigarette smoke throughout gestation increased the incidence and growth rate of EL-4 cells (mouse T-cell lymphoma) - induced tumors in male offspring, as well as reduced cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity in male offspring at 5 and 10 weeks after birth (Ng et al., 2006). Ng et al. (2006) findings support epidemiologic data indicating that children of mothers who smoke during pregnancy have a greater risk of developing cancer later in life. The decreased macrophage number, as well as decreased IFN-γ production in male offspring in the present study may explain the increased susceptibility to tumor incidence and growth in male offspring exposed to cigarette smoke in utero.

In summary, we have demonstrated that prenatal exposure to environmentally relevant Cd levels causes persistent immunomodulatory effects in murine offspring. Thymocyte phenotype analysis determined that these effects are cell type-specific, whereas analysis of splenocyte phenotype demonstrates a cell type- and sex-specific effect. The cytokine profiles suggest an effect on peripheral Th1 cells in females and to a lesser degree in males. The decrease in Th1 type cytokine production in females and the decreases in IFN-γ production and macrophage cell number in males may lead to increased susceptibility of the offspring to infections and tumor growth. The two major findings that defy simple explanation are a marked increase in anti-bacterial antibody levels and a marked decrease in the numbers of splenic CD8+CD223+ cells. These findings suggest that even very low exposure to Cd during gestation may result in long term detrimental effects on the immune system of the offspring, possibly resulting in cancer at adulthood, thus reinforcing that exposure to Cd during pregnancy should be limited.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Prenatal exposure to Cd causes no thymocyte phenotype changes in the offspring

Analysis of the splenocyte phenotype demonstrates a macrophage-specific effect only in male offspring

The cytokine profiles suggest an effect on peripheral Th1 cells in female and to a lesser degree in male offspring

There was a marked increase in serum anti-streptococcal antibody levels after immunization in both sexes

There a marked decrease in the numbers of splenic CD8+CD223+ cells in both sexes

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants [ES015539 to J.B.B and GM103488, RR032138 and RR020866 for flow cytometry].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Akesson A, Berglund M, Schutz A, Bjellerup P, Bremme K, Vahter M. Cadmium exposure in pregnancy and lactation in relation to iron status. American journal of public health. 2002;92:284–287. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmanov AA, Reed DR, Beauchamp GK, Tordoff MG. Food intake, water intake, and drinking spout side preference of 28 mouse strains. Behav Genet. 2002;6:435–43. doi: 10.1023/a:1020884312053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn SD, Shin H, Haining WN, Zou T, Workman CJ, Polley A, Betts MR, Freeman GJ, Vignali DAA, Wherry EJ. Coregulation of CD8+ T cell exhaustion by multiple inhibitory receptors during chronic viral infection. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:29–37. doi: 10.1038/ni.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaylock BL, Holladay SD, Comment CE, Heindel JJ, Luster MI. Exposure to tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) alters fetal thymocyte maturation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1992;112:207–213. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(92)90189-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgman RF, Au B, Chandra RK. Immunopathology of chronic cadmium administration in mice. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1986;8:813–817. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(86)90019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks DR, Mucci LA, Hatch EE, Cnattingius S. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and risk of brain tumors in the offspring. A prospective study of 1.4 million Swedish births. Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15:997–1005. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-1123-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe SY, Kim SJ, Kim HG, Lee JH, Choi Y, Lee H, Kim Y. Evaluation of estrogenicity of major heavy metals. The Science of the total environment. 2003;312:15–21. doi: 10.1016/S0048-9697(03)00190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colino J, Shen Y, Snapper CM. Dendritic cells pulsed with intact Streptococcus pneumoniae elicit both protein- and polysaccharide-specific immunoglobulin isotype responses in vivo through distinct mechanisms. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1–13. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook ME. Anthropogenic Sources of Cadmium in Canada; National Workshop on Cadmium Transport into Plants, Canadian Network of Toxicology Centres; Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Descotes J. Immunotoxicology of cadmium. IARC Sci Publ. 1992:385–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DHHS . Treating tobacco use and dependence U.S. DHHS, PHS; Rockville, MD: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dong S, Shen H-M, Ong C-N. Cadmium-induced apoptosis and phenotypic changes in mouse thymocytes. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2001;222:11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elinder CG, Lind B, Kjellstrom T, Linnman L, Friberg L. Cadmium in kidney cortex, liver, and pancreas from Swedish autopsies. Estimation of biological half time in kidney cortex, considering calorie intake and smoking habits. Archives of environmental health. 1976;31:292–302. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1976.10667239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faroon O, Ashizawa A, Wright S, Tucker P, Jenkins K, Ingerman L, Rudisill C. In: Toxicological Profile for Cadmium. Registry A. f. T. S. a. D., editor. Centers for Disease Control; Atlanta: 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippini G, Farinotti M, Ferrarini M. Active and passive smoking during pregnancy and risk of central nervous system tumours in children. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology. 2000;14:78–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2000.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippini G, Farinotti M, Lovicu G, Maisonneuve P, Boyle P. Mothers’ active and passive smoking during pregnancy and risk of brain tumours in children. International journal of cancer. 1994;57:769–774. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910570602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frery N, Nessmann C, Girard F, Lafond J, Moreau T, Blot P, Lellouch J, Huel G. Environmental exposure to cadmium and human birthweight. Toxicology. 1993;79:109–118. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(93)90124-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Morales P, Saceda M, Kenney N, Kim N, Salomon DS, Gottardis MM, Solomon HB, Sholler PF, Jordan VC, Martin MB. Effect of cadmium on estrogen receptor levels and estrogen-induced responses in human breast cancer cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1994;269:16896–16901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosso JF, Kelleher CC, Harris TJ, Maris CH, Hipkiss EL, De Marzo A, Anders R, Netto G, Getnet D, Bruno TC, Goldberg MV, Pardoll DM, Drake CG. LAG-3 regulates CD8+ T cell accumulation and effector function in murine self- and tumor-tolerance systems. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3383–3392. doi: 10.1172/JCI31184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson ML, Brundage KM, Schafer R, Tou JC, Barnett JB. Prenatal cadmium exposure dysregulates sonic hedgehog and Wnt/[beta]-catenin signaling in the thymus resulting in altered thymocyte development. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2010;242:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemdan NY, Emmrich F, Sack U, Wichmann G, Lehmann J, Adham K, Lehmann I. The in vitro immune modulation by cadmium depends on the way of cell activation. Toxicology. 2006;222:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holladay SD, Smialowicz RJ. Development of the murine and human immune system: differential effects of immunotoxicants depend on time of exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(Suppl 3):463–473. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s3463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovland DN, Jr., Machado AF, Scott WJ, Jr., Collins MD. Differential sensitivity of the SWV and C57BL/6 mouse strains to the teratogenic action of single administrations of cadmium given throughout the period of anterior neuropore closure. Teratology. 1999;60:13–21. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199907)60:1<13::AID-TERA6>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IARC . Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risk of Chemicals to Humans. IARC; Lyon, France: 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquillet G, Barbier O, Rubera I, Tauc M, Borderie A, Namorado MC, Martin D, Sierra G, Reyes JL, Poujeol P, Cougnon M. Cadmium causes delayed effects on renal function in the offspring of cadmium-contaminated pregnant female rats. American journal of physiology. 2007;293:F1450–1460. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00223.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarup L, Berglund M, Elinder CG, Nordberg G, Vahter M. Health effects of cadmium exposure--a review of the literature and a risk estimate. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health. 1998;24(Suppl 1):1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin T, Lu J, Nordberg M. Toxicokinetics and biochemistry of cadmium with special emphasis on the role of metallothionein. Neurotoxicology. 1998;19:529–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MD, Kenney N, Stoica A, Hilakivi-Clarke L, Singh B, Chepko G, Clarke R, Sholler PF, Lirio AA, Foss C, Reiter R, Trock B, Paik S, Martin MB. Cadmium mimics the in vivo effects of estrogen in the uterus and mammary gland. Nature medicine. 2003;9:1081–1084. doi: 10.1038/nm902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil DE, Mehlmann T, Butterworth L, Peden-Adams MM. Gestational Exposure to Perfluorooctane Sulfonate Suppresses Immune Function in B6C3F1 Mice. Toxicol. Sci. 2008;103:77–85. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Sharma RP. Cadmium-induced apoptosis in murine macrophages is antagonized by antioxidants and caspase inhibitors. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2006;69:1181–1201. doi: 10.1080/15287390600631144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippler M, Ekstrom EC, Lonnerdal B, Goessler W, Akesson A, El Arifeen S, Persson LA, Vahter M. Influence of iron and zinc status on cadmium accumulation in Bangladeshi women. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;222:221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krocova Z, Macela A, Kroca M, Hernychova L. The immunomodulatory effect(s) of lead and cadmium on the cells of immune system in vitro. Toxicol In Vitro. 2000;14:33–40. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2333(99)00089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafuente A, Gonzalez-Carracedo A, Romero A, Esquifino AI. Effect of cadmium on lymphocyte subsets distribution in thymus and spleen. J Physiol Biochem. 2003;59:43–48. doi: 10.1007/BF03179867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafuente A, Gonzalez-Carracedol A, Esquifino AI. Differential effects of cadmium on blood lymphocyte subsets. Biometals. 2004;17:451–456. doi: 10.1023/b:biom.0000029441.20037.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauwerys R, Buchet JP, Roels H, Bernard A, Gennart JP. Biological aspects of occupational exposure to cadmium and several other metals. Revue d’epidemiologie et de sante publique. 1986;34:280–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Liu Y, Habeebu SS, Klaassen CD. Metallothionein-null mice are highly susceptible to the hematotoxic and immunotoxic effects of chronic CdCl2 exposure. Toxicol.Appl.Pharmacol. 1999a;159:98–108. doi: 10.1006/taap.1999.8718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Liu Y, Habeebu SS, Klaassen CD. Metallothionein-null mice are highly susceptible to the hematotoxic and immunotoxic effects of chronic CdCl2 exposure. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1999b;159:98–108. doi: 10.1006/taap.1999.8718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiacono NJ, Graziano JH, Kline JK, Popovac D, Ahmedi X, Gashi E, Mehmeti A, Rajovic B. Placental cadmium and birthweight in women living near a lead smelter. Archives of environmental health. 1992;47:250–255. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1992.9938357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackova NO, Lenikova S, Fedorocko P, Brezani P, Fedorockova A. Effects of cadmium on haemopoiesis in irradiated and non-irradiated mice: 2. Relationship to the number of circulating blood cells and haemopoiesis. Physiological research/Academia Scientiarum Bohemoslovaca. 1996a;45:101–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackova NO, Lenikova S, Fedorocko P, Brezani P, Fedorockova A. Effects of cadmium on haemopoiesis in irradiated and non-irradiated mice: 2. Relationship to the number of circulating blood cells and haemopoiesis. Physiol Res. 1996b;45:101–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TE, Golemboski KA, Ha RS, Bunn T, Sanders FS, Dietert RR. Developmental exposure to lead causes persistent immunotoxicity in Fischer 344 rats. Toxicol Sci. 1998;42:129–135. doi: 10.1006/toxs.1998.2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minetti A, Reale CA. Sensorimotor developmental delays and lower anxiety in rats prenatally exposed to cadmium. J Appl Toxicol. 2006;26:35–41. doi: 10.1002/jat.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morselt AFW, Leene W, DeGroot C, Kipp JBA, Evers M, Roelofsen AM, Bosch KS. Differences in immunological susceptibility to cadmium toxicity between two rat strains as demonstrated with cell biological methods. Effect of cadmium on DNA synthesis of thymus lymphocytes. Toxicology. 1988;48:127–139. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(88)90095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa A, Holladay SD, Goff M, Witonsky SG, Kerr R, Reilly CM, Sponenberg DP, Gogal RM., Jr An enhanced postnatal autoimmune profile in 24 week-old C57BL/6 mice developmentally exposed to TCDD. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2008;232:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng SP, Silverstone AE, Lai Z-W, Zelikoff JT. Effects of Prenatal Exposure to Cigarette Smoke on Offspring Tumor Susceptibility and Associated Immune Mechanisms. Toxicol. Sci. 2006;89:135–144. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg GF. Lung cancer and exposure to environmental cadmium. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:99–101. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70548-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson IM, Bensryd I, Lundh T, Ottosson H, Skerfving S, Oskarsson A. Cadmium in blood and urine--impact of sex, age, dietary intake, iron status, and former smoking--association of renal effects. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:1185–1190. doi: 10.1289/ehp.021101185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak N, Khandelwal S. Influence of cadmium on murine thymocytes: potentiation of apoptosis and oxidative stress. Toxicol Lett. 2006a;165:121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak N, Khandelwal S. Oxidative stress and apoptotic changes in murine splenocytes exposed to cadmium. Toxicology. 2006b;220:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak N, Khandelwal S. Role of oxidative stress and apoptosis in cadmium induced thymic atrophy and splenomegaly in mice. Toxicology Letters. 2007;169:95–108. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak N, Khandelwal S. Impact of cadmium in T lymphocyte subsets and cytokine expression: differential regulation by oxidative stress and apoptosis. Biometals. 2008;21:179–187. doi: 10.1007/s10534-007-9106-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasek M, Blanusa M, Kostial K, Laskey JW. Placental cadmium and progesterone concentrations in cigarette smokers. Reproductive toxicology (Elmsford, N.Y. 2001;15:673–681. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(01)00174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillet S, D’Elia M, Bernier J, Bouquegneau JM, Fournier M, Cyr DG. Immunomodulatory Effects of Estradiol and Cadmium in Adult Female Rats. Toxicological Sciences. 2006;92:423–432. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez DC, Gimenez MS. Lipid modification in mouse peritoneal macrophages after chronic cadmium exposure. Toxicology. 2002;172:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(01)00560-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar KD, de la Rosa P, Barnett JB, Schafer R. The Polysaccharide Antibody Response after Streptococcus pneumoniae Vaccination Is Differentially Enhanced or Suppressed by 3,4-Dichloropropionanilide and 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid. Toxicological Sciences. 2005;87:123–133. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuz J, Kaletsch U, Kaatsch P, Meinert R, Michaelis J. Risk factors for pediatric tumors of the central nervous system: results from a German population-based case-control study. Medical and pediatric oncology. 2001;36:274–282. doi: 10.1002/1096-911X(20010201)36:2<274::AID-MPO1065>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott WJ, Jr., Schreiner CM, Goetz JA, Robbins D, Bell SM. Cadmium-induced postaxial forelimb ectrodactyly: association with altered sonic hedgehog signaling. Reproductive toxicology (Elmsford, N.Y. 2005;19:479–485. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H, Wherry EJ. CD8 T cell dysfunction during chronic viral infection. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2007;19:408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder JE, Filipov NM, Parsons PJ, Lawrence DA. The efficiency of maternal transfer of lead and its influence on plasma IgE and splenic cellularity of mice. Toxicol Sci. 2000;57:87–94. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/57.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogawa N, Onodera K, Sogawa CA, Mukubo Y, Fukuoka H, Oda N, Furuta H. Bisphenol A enhances cadmium toxicity through estrogen receptor. Methods and findings in experimental and clinical pharmacology. 2001;23:395–399. doi: 10.1358/mf.2001.23.7.662127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soukupova D, Dostal M, Piza J. Developmental toxicity of cadmium in mice. II. Immunotoxic effects. Functional and developmental morphology. 1991;1:31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart GA, Lowrey JA, Wakelin SJ, Fitch PM, Lindey S, Dallman MJ, Lamb JR, Howie SEM. Sonic Hedgehog Signaling Modulates Activation of and Cytokine Production by Human Peripheral CD4+ T Cells. 2002:5451–5457. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoica A, Katzenellenbogen BS, Martin MB. Activation of estrogen receptor-alpha by the heavy metal cadmium. Molecular endocrinology (Baltimore, Md. 2000;14:545–553. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.4.0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thijssen S, Maringwa J, Faes C, Lambrichts I, Van Kerkhove E. Chronic exposure of mice to environmentally relevant, low doses of cadmium leads to early renal damage, not predicted by blood or urine cadmium levels. Toxicology. 2007;229:145–56. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahter M, Akesson A, Liden C, Ceccatelli S, Berglund M. Gender differences in the disposition and toxicity of metals. Environmental research. 2007;104:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahter M, Berglund M, Akesson A, Liden C. Metals and women’s health. Environmental research. 2002;88:145–155. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2002.4338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waalkes MP, Coogan TP, Barter RA. Toxicological principles of metal carcinogenesis with special emphasis on cadmium. Critical reviews in toxicology. 1992;22:175–201. doi: 10.3109/10408449209145323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter O, Moser K, Mohr E, Zotos D, Kaminski H, Szyska M, Roth K, Wong DM, Dame C, Tarlinton DM, Schulze H, MacLennan ICM, Manz RA. Megakaryocytes constitute a functional component of a plasma cell niche in the bone marrow. Blood. 2010;116:1867–75. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-259457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu ZQ, Khan AQ, Shen Y, Schartman J, Peach R, Lees A, Mond JJ, Gause WC, Snapper CM. B7 requirements for primary and secondary protein- and polysaccharide-specific Ig isotype responses to Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Immunol. 2000;165:6840–6848. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.6840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu ZQ, Vos Q, Shen Y, Lees A, Wilson SR, Briles DE, Gause WC, Mond JJ, Snapper CM. In vivo polysaccharide-specific IgG isotype responses to intact Streptococcus pneumoniae are T cell dependent and require CD40- and B7-ligand interactions. J Immunol. 1999;163:659–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.