Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNA) are a group of small noncoding RNAs that regulate gene expression. The discovery of these small RNAs has added a new layer of complexity to molecular biology. Every day, new advances are being made in understanding the biochemistry and genetics of miRNAs and their roles in cellular function and homeostasis. Studies indicate diverse roles for miRNAs in inner ear biology and pathogenesis. This article reviews recent developments in miRNA research in the field of inner ear biology. A brief history of miRNA discovery is discussed, and their genomics and functional roles are described. Advances in the understanding of miRNA involvement in inner ear development in the zebrafish and the mouse are presented. Finally, this review highlights the potential roles of miRNAs in genetic hearing loss, hair cell regeneration, and inner ear pathogenesis resulting from various pathological insults.

Keywords: microRNA, inner ear, hair cell, zebrafish, mouse, review, pathology, hearing loss

MicroRNAs (miRNA) are a class of small noncoding RNAs that are processed from endogenous gene transcripts. They are involved in diverse physiological, developmental, and pathological processes by regulating the expression of target messenger RNAs (mRNAs). In the past several years, emerging evidence has linked miRNAs to inner ear biology and pathogenesis. Several excellent reviews on miRNA expression and action in the inner ear have been published (Friedman et al., 2009a; Kopecky et al., 2011; Lewis et al., 2010; Li et al., 2010a; Soukup, 2009). In the current review, we discuss the latest developments in miRNA research with a focus on the potential role of miRNAs in inner ear development, genetic hearing loss, hair cell regeneration and inner ear stress.

1. History of miRNA Research

The first miRNA, Lin-4, was discovered in 1993 (Lee et al., 1993) in a study of developmental mutations in Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans). Initially, lin-4 was believed to be a protein-coding gene (Chalfie et al., 1981; Sulston et al., 1981). However, a subsequent investigation revealed that the lin-4 gene encodes a small noncoding RNA, and not a protein (Sulston et al., 1981).

Evidence linking miRNAs with mRNAs was obtained from the observation that the lin-4 mutant exhibits developmental phenotypes similar to those found in C. elegans with a mutation in the 3’ untranslated region (UTR) of the lin-14 mRNA (Lee et al., 1993; Vella et al., 2005). Further analysis revealed complementary sequences between lin-4 RNA and the 3’UTR of lin-14. Moreover, this discovery predicted that RNA/mRNA duplex is phylogenetically conserved (Lall et al., 2006). These observations indicated that the newly discovered small RNA molecules were associated with mRNAs.

Another small RNA identified in C. elegans, let-7, has also been found in the Drosophila melanogaster and human genomes, indicating that small RNA genes are conserved between species (Pasquinelli et al., 2000). Like lin-4, let-7 acts as an antisense translational repressor of mRNAs that encode regulatory proteins of developmental timing in C. elegans. As both lin-4 and let-7 are involved in controlling developmental timing, they were initially referred to as “small temporal RNAs”. Over time, as many more small RNAs were discovered, the term “miRNA” was coined, as miRNAs appear in both embryonic cells and in mature cells. In addition to development, miRNAs have subsequently been associated with a variety of cellular functions (Ambros et al., 2003).

Over the past decade, researchers in a wide variety of disciplines have studied miRNAs. More than 1100 miRNAs in humans, 717 in mice, 387 in rats, 186 in Drosophila, and 233 in C. elegans have been identified to date (www.microRNA.org), and these numbers are expected to increase. We are just beginning to understand the role of miRNAs in cell biology and pathogenesis.

2. General Function of miRNAs

Most miRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II (Isik et al., 2010; Krol et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2004) to produce a primary miRNA transcript, which is subsequently processed by a microprocessor complex consisting of Drosha, (a type-III RNase) and its cofactor DGCR8 (DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 8) to generate a precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA) (Han et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2003). The pre-miRNA is then transported out of the nucleus to the cytoplasm by exportin-5 and its cofactor Ran-GTP (Ran–guanosine triphosphate). In the cytoplasm, the pre-miRNA is processed by Dicer (a type-III RNase) and TRBP (trans-activation response RNA-binding protein) to produce a miRNA duplex (Chendrimada et al., 2005; Koscianska et al., 2011; Kurihara et al., 2010). The resulting duplex is further processed into mature miRNA, which is a single-stranded 20–22-nucleotide RNA molecule (Cai et al., 2004; Gu et al., 2011; Matranga et al., 2005; Rand et al., 2004; Rand et al., 2005; Sontheimer et al., 2004).

The functional role of a miRNA depends on the identity of its target mRNAs (Long et al., 2008; Long et al., 2007). While miRNAs are known to target primarily 3’UTRs, they can also target 5’UTRs (Lee et al., 2009; Lytle et al., 2007). During the mRNA/miRNA interaction, base-pairing occurs between the mRNA and the seed region of the miRNA, which consists of nucleotides 2–7 or 2–8 of the miRNA (Brennecke et al., 2005; Farh et al., 2005; Lewis et al., 2005).

Increasing evidence indicates that miRNAs inhibit mRNA gene expression through translational repression and/or mRNA degradation (Doench et al., 2004; Engels et al., 2006; Huntzinger et al., 2011). Translational repression of an mRNA occurs when a mismatch exists between the miRNA and the target mRNA. Currently, different mechanisms for translational repression have been proposed, which include targeting eukaryotic translation-initiation factors (eIFs), the 40S, 60S and 80S ribosomal subunits, ribosomal elongation and ribosomal drop off, and mRNA circularization (Mathonnet et al., 2007; Pillai et al., 2007; Valencia-Sanchez et al., 2006). When a perfect or near perfect match exists between a miRNA and a target mRNA, site-specific cleavage of the mRNA occurs, followed by its degradation. mRNA target degradation can either be catalyzed by arognaute proteins or through processes such as deadenylation, decapping, and exonucleolytic digestion (Eulalio et al., 2008; Iwasaki et al., 2009; Okamura et al., 2004). Apart from these well-studied targeting mechanisms, alternative mechanisms have been described in the literature. However, a description of these studies is beyond the scope of this article. However, nonetheless, other articles have provided comprehensive information on this subject (Ajay et al., 2010; Djuranovic et al., 2011; Eckhardt et al., 2011; Olena et al., 2010; Walters et al., 2010).

Interestingly, the regulatory process mediated by miRNA/mRNA interactions does seem to be conserved across species and a few cross-species miRNA/mRNA regulatory pairs have been identified (Grun et al., 2005; Gu et al., 2008; Pasquinelli et al., 2000), suggesting that miRNA regulation is a fundamental function of the cell. The regulatory influence of miRNAs on their target mRNAs has been implicated in a variety of biological processes, cellular functions and diseases, including inner ear development and pathogenesis.

3. miRNAs and Inner Ear Development

4.1. Expression pattern of miRNAs during inner ear development

Investigation of miRNAs in inner ear biology began with a study of miRNA expression in zebrafish during embryonic development (Wienholds et al., 2005). This investigation discovered that miRs-183, -182, -96 and -200a are expressed in developing inner ears. This finding was subsequently confirmed by other investigators (Kapsimali et al., 2007; Li et al., 2010b). Robust expression of miR-183 was detected throughout the entire developmental process. Importantly, these studies revealed spatially and temporally dependent expression patterns of miRNAs (Table 1).

Table 1.

miRNA expression patterns in the inner ears of zebrafish

| Developmental Stage | miRNA | Site of Expression | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16-hpf | miR-183, 96 | Hair Cells | Wienholds et al, 2005 Li et al., 2010 |

| 1, 2, 3, 5-dpf | mi R-183, 182, 96 | Hair Cells | Wienholds et al., 2005,Kapsimali et al., 2007 Li et al., 2010 |

| 12, 16-hpf | miR-145 | Ear | Wienholds et al., 2005 |

| 1 ,2, 3 , 5-dpf | miR-1 45 | Ear | Wienholds et al., 2005 |

| 5-dpf | miR-200a | Sensory epithelium | Wienholds et al., 2005 |

hpf: hours post fertilization

dpf: days post fertilization

Like zebrafish, mice exhibit differential expression patterns of miRNAs during ear development. Thus far, hundreds of miRNAs have been identified in developing inner ears (Friedman et al., 2009b; Wang et al., 2010a; Weston et al., 2006). The number of expressed miRNAs in the inner ear increases during embryonic development (Wang et al., 2010a), but remains relatively stable during postnatal stages (Weston et al., 2006). Many miRNAs are expressed through adulthood, indicating that miRNAs participate in both the development and maintenance of inner ear structures.

Most miRNA profiling studies were carried out using microarrays. While this technique facilitates screening large numbers of miRNAs, it is limited in its ability to detect previously unknown miRNAs. This limitation has been partially resolved by RNA-sequencing techniques, which enable whole transcriptome profiling and the identification of novel miRNAs (Morozova et al., 2009; Mortazavi et al., 2008; Remenyi et al., 2010). It is expected that with continued improvement of this technology, more novel miRNAs and their associated targets will be identified in the inner ear.

In addition to miRNA profiling, several studies have focused on the expression patterns of the miR-183 cluster, composed of miRs-183, -182 and -96, which originate from a common primary transcript (Ryan et al., 2006; Sacheli et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2010a; Weston et al., 2006; Weston et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2007). The expression of this cluster of miRNAs starts at E9.5, an early stage of development within the otic vesicle (Sacheli et al., 2009). The initial expression pattern appears to be broadly distributed. As embryonic development proceeds, expression is gradually confined to sensory cells in the cochlea and the vestibule end-organs, as well as in the spiral and the vestibular ganglia (Table 2). During inner ear development, two expression features of the miR-183 cluster exist. First, the expression onset in inner hair cells precedes that in outer hair cells (Weston et al., 2011), consistent with the earlier differentiation of inner hair cells (Dabdoub et al., 2008; Kelley, 2007). Second, the cochlear sensory epithelium exhibits a gradient level of expression (Weston et al., 2011). At P0, these miRNAs display increased expression at the base that gradually decreases towards the apex with greater expression in outer hair cells compared to inner hair cells. Conversely, in mature cochleae at P37 and P100, these miRNAs display increased expression at the apex that gradually decreases towards the base. Apical cells display similar outer hair cell and inner hair cell expression patterns but basal cells display increased expression in inner hair cells compared to the outer hair cells. The presence of these temporal and spatial expression patterns suggests that the miR-183 cluster is involved in coordinating sensory cell specific development and maintenance.

Table 2.

miRNA expression patterns in embryonic mouse inner ear

| Developmental Stage | miRNA | Tissue | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| E9.5 | miR-182/183 | Otic Vesicle | Sacheli et al., 2009 |

| E10.5 | miR-182 | Otocyst | Wang et al., 2010 |

| E11 .5 | miR-96/182/183 | Otic Vesicle | Sacheli et al., 2009 |

| E12.5 | miR-182/183 | Vestibule Cells of cochlear duct | Sacheli et al., 2009 |

| E12.5 | miR-96/182/183 | Statoacoustic ganglia | Weston et al., 2011 |

| E14.5 | miR-96/182/183 | Hair cells in luminal layer of vestibule | Sacheli et al., 2009 |

| E14.5 | miR-182 | Spiral ganglion (SG) Lower epithelial ridge Greater epithelial ridge (GER) | Wang et al., 2010 |

| E14.5 | miR-96/182/183 | Inner ear ganglia Vestibular sensory epithelia | Weston et al., 2011 |

| E15.5 | miR-182 | GER, SG Cochlea hair cells Vestibule | Wang et al., 2010 |

| E15.5 | miR-96/182/183 | GER, SG Cochlear duct cells Sensory epithelia (SE) | Sacheli et al., 2009 |

| E16.5 | miR-96/182/183 | Sensory ganglia Transient cells of GER SG,SE | Weston et al., 2011 |

| E17.5 | miR-96/182/183 | GER, SE Cochlea/vestibule hair cells | Sacheli et al., 2009 |

| E18.5 | miR-96/182/183 | Sensory ganglia Inner ear hair cells | Weston et al., 2011 |

Interestingly, the reported expression patterns of the miR-183 cluster differ in various studies. Sacheli and colleagues reported that miR-96 was not expressed after P4 (Sacheli et al., 2009). However, other studies demonstrated the expression of miR-96 during late developmental and early adult stages (Lewis et al., 2009; Weston et al., 2011). Similarly, Sacheli and colleagues reported that the miR-183 cluster was not detected in adult mice (Sacheli et al., 2009), but other studies reported strong expression in the sensory cells of adult mice (Lewis et al., 2009; Weston et al., 2006; Weston et al., 2011). In addition to the reported difference in the temporal expression pattern, the reported spatial pattern of miRNA expression is also different. miRs-183 and -182 were found in the inner sulcus and spiral limbus from P11 onwards in a study by Sacheli and colleagues (Sacheli et al., 2009), whereas the expression of these miRNAs was found in sensory cells at the same development stage in a study by Weston and colleagues (Weston et al., 2011). The causes of these variations are not known, but they may be related to the differences in the techniques used by the different studies for tissue processing and/or miRNA detection. For example, in situ hybridizations were performed using samples prepared by means of a cryostat, paraffin embedding or whole mount techniques, which may have led to the observed discrepancies. Additionally, another important factor may be the specificity of the oligonucleotide probes (purchased from different companies), which, due to technological advancements made since 2009 (Sacheli et al., 2009) to 2011 (Weston et al., 2011), may have led to differences in probe specificity.

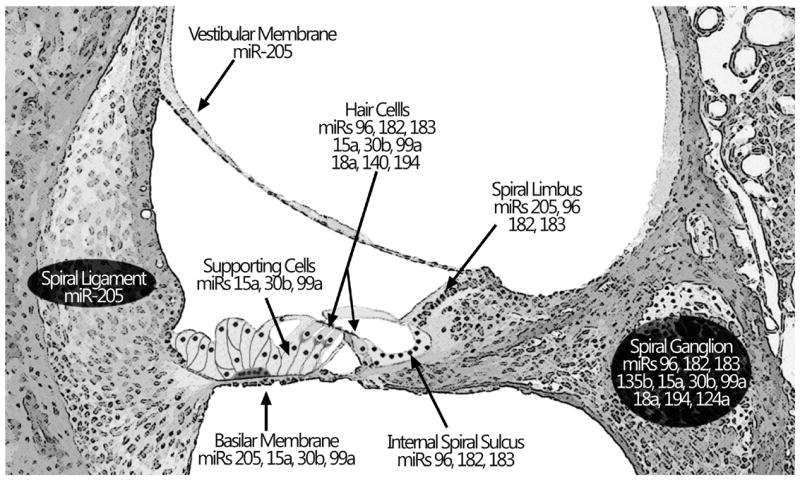

In addition to the miR-183 cluster, other miRNAs are expressed in the inner ear in either a time-dependent manner or a stable manner (Table 3 (Elkan-Miller et al., 2011; Friedman et al., 2009b; Wang et al., 2010a; Weston et al., 2006). Moreover, the expression of many miRNAs is tissue- or cell-type specific as shown in Figure 1. The spatial differences in miRNA expression patterns correlate with the progression of hair cell differentiation. An analysis of this correlation has provided important clues in our understanding of miRNA function in regulating inner ear development.

Table 3.

miRNA expression patterns in the inner ears of postnatal mice

| Developmental Stage | miRNA | Cochlear Site of Expression | Vestibular Site of Expression | Neural Site of Expression | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P0 | miR-96/182/183 | Hair cells | Hair cells | Spiral ganglia Vestibular ganglia | Weston et al., 2006, 2011 |

| P0 | miR-96/182/183 | Hair cells Greater epithelial ridge | Hair cells | Spiral ganglia | Sacheli et al., 2009 |

| P0 | miR-135b | — | Hair cells | Spiral ganglia Vestibular ganglia | Miller et al., 2011 |

| P0 | miR-205 | Cochlear cells Spiral ligament cells Reissner’s membrane Basilar membrane Apical spiral limbus | — | — | Miller et al., 2011 |

| P0 | miR-182 | Hair cells | Hair cells | Spiral ganglia | Friedman et al., 2009 |

| P0 | miR-15a/30b/99a | Hair cells Supporting cells Basilar membrane | Hair cells | Spiral ganglia | Friedman et al., 2009 |

| P0 | miR-199a | Cochlear cells | — | — | Friedman et al., 2009 |

| P0 | miR-18a | Hair cells | Hair cells | Spiral ganglia | Friedman et al., 2009 |

| P1 | miR-182/140 | Hair cells | Hair cells | Wang et al., 2010 | |

| P1 | miR-194 | Hair cells | Hair cells | Spiral ganglia | Wang et al., 2010 |

| P0-P2 | miR-96/182/183 | Hair cells | Hair cells | Spiral ganglia | Sacheli et al., 2009 |

| P4-P11 | miR-96 | Inner sulcus Spiral limbus | — | — | Sacheli et al., 2009 |

| P4-P8 | miR-182/183 | Hair cells | Hair cells | — | Sacheli et al., 2009 |

| P4-P14 | miR-96/182/183 | — | — | Spiral ganglia | Sacheli et al., 2009 |

| P5 | miR-124a | — | — | Spiral ganglia Vestibular ganglia | Weston et al., 2006 |

| P5 | miR-100a | — | — | Vestibular ganglia | Weston et al., 2006 |

| P11 | miR-182/183 | Inner sulcus Spiral limbus | — | — | Sacheli et al., 2009 |

| P37-P100 | miR-96/182/183 | Hair cells | — | — | Weston et al., 2011 |

Note: “—” indicates no data available

Figure 1.

Schematic of cochlear structures depicting localization of miRNA expression in postnatal mice

4.2. Functional roles of miRNAs in inner ear development

4.2.1. miRNAs are required for embryonic development of the inner ear and postnatal maintenance of hair cell fate

To understand the functional role of miRNAs in inner ear development, several mutant mouse and zebrafish models have been developed. In zebrafish, mutant embryos lacking both maternal and zygotic Dicer activity lose their pre-miRNA processing ability and, consequently, are unable to generate mature miRNAs (Giraldez et al., 2005). These embryos have severe morphogenetic defects, including defective ear development, suggesting that miRNAs play an essential role in the early development of the inner ear.

In mouse models, animals in which Dicer is completely knocked out die during early gestation due to severe morphological and developmental defects (Bernstein et al., 2003). This indicates that small RNAs, including miRNAs, are vital for cellular function and embryonic survival. To investigate miRNA function at later developmental stages, the Cre-loxP recombination system has been employed to generate conditional miRNA knockout models (Friedman et al., 2009b; Kersigo et al., 2011; Soukup et al., 2009; Weston et al., 2011). These models use various Cre lines, in which the Cre recombinase is expressed using diverse regulatory elements, including the Pax2, Pou4f3, Foxg1 and Atoh1 promoters. Because these promoters control Cre recombinase expression in a tissue- or cell type-selective fashion, miRNAs are also depleted in a selective manner (Table 4).

Table 4.

Conditional Dicer knockout mouse models

| Promoter Gene | Inner Ear Cre Expression | Timing of Cre Expression | Timing of milNA depletion | Timing of Developmental defect | Defects of Inner ear | Lethality | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pax2 | Otic Placode | E8.5 | miR-124 at E11.5 Residual miR-183 at E17.5 | E17.5 | Truncated inner ear structures | E18.5 | Soukup et al., 2009 |

| Atoh1 | Hair cells | E12.5-E14.5 | miR-183 at P18 | P28 | Loss of sensory cells | P28 | Weston et al., 2011 |

| Pou4f3/Brn3c | Inner ear: hair cell and some supporting cells | P6 | — | P38 | Malformed hair cells | — | Friedman et al., 2009 |

| Foxg1 | Inner ear: Neurosensory cells | — | miR-124 at E12.5 | E18.5 | Complete loss of neurosensory cells and near complete loss of the ear | Perinatal stage | Kersigo et al., 2011 |

Note: “—” indicates no data available

Mice that have had Dicer knocked out using Pax2-Cre or Foxg1-Cre drivers exhibit rapid, neuron-specific miRNA depletion during embryonic development (Kersigo et al., 2011; Soukup et al., 2009). Loss of miRNAs leads to broad developmental defects, and embryonic lethality occurs at approximately E18.5 (Pax2-Cre model) or perinatally (Foxg1-Cre model). These mice exhibit early disruption of inner ear development marked by apoptotic sensory cells and neuronal death. These observations indicate miRNAs play an essential role in the embryonic development of the inner ear. Interestingly, even though Dicer is knocked out, residual mature miRNA expression still persists for several days. This may be attributed to the presence of residual miRNAs and Dicer produced before Dicer deletion (Gantier et al., 2011; Soukup et al., 2009). Variability in residual miRNAs may contribute to the variability that is observed in the development of inner ear defects in knockout models (Soukup et al., 2009).

Conditional ablation of miRNAs has also been used to investigate the role of miRNAs in the maintenance of sensory cells during the postnatal maturation of the cochlea. The mouse models, Atoh1-Cre conditional Dicer knockout, exhibit delayed miRNA depletion (Table 4 (Weston et al., 2011). The Atoh1-Dicer knockout model has normal development of hair cells at P16, but shows a considerable loss of basal hair cells at P28 (Weston et al., 2011). Similarly, the Pou4f3-Cre conditional Dicer knockout model does not exhibit abnormalities in the sensory epithelium during embryonic development (Friedman et al., 2009b). However, at P38, the inner ear shows abnormal morphology in sensory cells including loss of stereocilia and malformation of cochlear hair cell shape. Auditory brainstem responses are also absent at this developmental stage. Interestingly, both models exhibit a graded level of sensory cell degeneration longitudinally along the cochlea with more severe malformations or increased loss of hair cells in the basal end of the cochlea, consistent with the degenerative patterns of aging, and noise-induced and ototoxic drug-induced cochlear damage (Bohne et al., 1987; Fechter et al., 1997; Forge et al., 2000; Hu et al., 2002; Sha et al., 2001). This suggests that miRNA dysfunction is also a potential contributor to cochlear pathogeneses. We now know that miRNAs are required for both the embryonic development of the inner ear and the postnatal maintenance of sensory cell homeostasis and function.

The Cre-Dicer knockout models are a valuable tool for investigating miRNA function. However, due to the broad impact of knocking out Dicer on miRNA expression, it is impossible to address the question as to the functional roles of individual miRNAs in inner ear development. In recent years, synthetic miRNAs and antisense oligonucleotides have been used to overexpress or inhibit miRNAs of interest (to be described in the following section). With these techniques, the functional roles of individual miRNAs can be assessed.

4.2.2. Functional role of the miR-183 cluster in inner ear development

The functional role of individual members of the miR-183 cluster in inner ear development has been investigated in zebrafish embryos (Li et al., 2010b). Injection of synthetic double-stranded miRs-182 or -96 into embryos promotes the growth of extra or ectopic hair cells, whereas injection of miR-183 leads to normal hair cell development. Clearly, even though miRs-183, -182, and -96 arise from the same primary transcript, their roles in embryonic development differ, possibly because of differences in their downstream targets.

Inhibition of the miR-183 cluster using morpholino antisense oligonucleotides also affects the normal development of the inner ear, leading to developmental stage-dependent defects. In the anterior and posterior macula, the magnitude of hair cell loss is related to the number of miRNAs inhibited. As the number of suppressed miR-183 cluster members increases from one (miR-96), to two (miR-183/182) to three (miR-183/182/96), the number of missing hair cells increases. Clearly, all members of the miR-183 cluster appear to participate in controlling the number of sensory cells, and their action is additive. The finding that both overexpression and inhibition of miRNAs disrupt hair cell development suggests that balanced expression of miRNAs is critical for normal hair cell development.

The functional role of miR-96, a member of the miR-183 cluster has also been documented in a mutant mouse model with a single base change in the seed region of miR-96 (Kuhn et al., 2011; Lewis et al., 2009). This mutant, induced by N-ethyl-N-nitrosurea (ENU) mutagenesis, exhibits progressive hearing loss in heterozygotes and complete hearing loss in homozygotes. Developmental arrest occurs in homozygotes with abnormal morphologies in stereocilia bundles occurring 4-5 days after birth. In heterozygotes, at 4–6 weeks, the mutant mice display outer hair cell degeneration. These morphological changes in hair cells coincide with the arrest of the physiological development of sensory cells at this developmental stage. These studies provide additional evidence for the involvement of miR-96 in the development of inner ear structures.

Thus far, the precise mechanisms by which miRNAs affect inner ear development are still not clear. Recent advances in target analysis, which will be described in the next section, has provided important clues for understanding miRNA regulation of inner ear development.

4. Target Analysis

miRNA regulation of cellular function is achieved by controlling the expression of target genes. Therefore, the identification of miRNA targets is an important step towards understanding the role of miRNAs in cellular function and pathogenesis. One research tool for predicting candidate targets for miRNAs is bioinformatic analysis. By combining different bioinformatic software packages, miRNA/mRNA target pairs can be discovered. Different software packages including miRanda, PicTar, TargetScan, PITA and STarMir use different algorithms to predict mRNA targets (Krek et al., 2005; Lewis et al., 2005; Long et al., 2008; Nielsen et al., 2007; Rehmsmeier et al., 2004). Each software has its own strengths and weaknesses, which are discussed in detail in the cited articles (Min et al., 2010; Thomas et al., 2010; Witkos et al., 2011; Xia et al., 2009).

The predicted targets for an individual miRNA can be sorted into functionally related groups by DAVID (the database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery), a bioinformatic resource that can identify related protein annotations and gene ontology terms (Huang da et al., 2009). One other database, TarBase, lists experimentally supported miRNA/mRNA interactions (Papadopoulos et al., 2009) providing insight into features of miRNA targeting and their role in various biological networks. Using bioinformatic analysis, several studies have predicted potential targets for selected miRNAs that are involved in inner ear development (Elkan-Miller et al., 2011; Friedman et al., 2009b; Lewis et al., 2009; Mencia et al., 2009). As each of these algorithms and databases can generate a large number of candidate targets, research has focused on those that are expressed in the inner ear and/or are known to participate in inner ear biology.

While bioinformatic software packages are capable of predicting multiple targets for miRNAs, the predicted targets need to be validated experimentally. To this end, microarrays or PCR assays have been used to confirm changes in the expression of mRNAs (Elkan-Miller et al., 2011; Hertzano et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2010b). Microarray analysis can not only confirm changes in mRNA levels predicted by bioinformatic assessment but can also determine the changes associated with downstream effects of miRNAs (Lewis et al., 2009). Moreover, a reverse prediction for identifying miRNAs of interest can be achieved by analyzing miRNA binding sites in selected target genes that are identified by microarray analysis. This strategy has been used to predict candidate miRNAs that are likely to be involved in inner ear development (Frucht et al., 2011; Frucht et al., 2010; Hertzano et al., 2011).

In addition to these techniques, another popular method for experimentally validating miRNA/mRNA interactions is the luciferase reporter assay (Krek et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2007). In the inner ear, application of this assay has led to advances in our understanding of miRNA/mRNA interactions (Table 5 (Elkan-Miller et al., 2011; Friedman et al., 2009b; Mencia et al., 2009; Solda et al., 2011; Weston et al., 2011). Target analysis has provided important clues for understanding miRNA function and has enabled us to prioritize future investigations to probe these functions.

Table 5.

Validated miRNA targets

| miRNA | Validated Targets | Experimental Model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-15a | SIc2a2 Bdnf Cldn 12 | Human Embryonic Kidney Cells (HEK-293T) | Friedman et al., 2009 |

| miR-96 | Aqp5 Myrip Celsr2 Rvk Odf2 | Mouse Embryonic Fibroblast Cells (NIH-3T3) | Mencia et al, 2009 |

| miR-96 | Acvr2b Myrip Cacnb4 | HeLa cells | Solda et al, 2011 |

| miR-135b | Psip1 | Human Breast Carcinoma Cells (Ca151 and MCF-7) | Elkan-Miller et al., 2011 |

| miR-182 | Sox2 | Human Embryonic Kidney Cells (HEK-293) | Weston et al, 2011 |

5. miRNAs and Genetic Hearing Loss

Since the completion of the human genome project, the exploration of the molecular basis of genetic hearing loss has been an area of intensive study (Hilgert et al., 2009; Mahdieh et al., 2010; Yan et al., 2008). Thus far, over 100 loci have been mapped for their connection to non-syndromic sensorineural hearing loss (NSHL; Hereditary Hearing Loss Homepage; http://hereditaryhearingloss.org). However, the molecular mechanisms responsible for genetic hearing loss remain unclear. In the past several years, great effort has been made to investigate the potential contribution of miRNAs to NSHL.

Interactions of miRNAs and mRNAs rely on the degree of complementarity of their nucleotide sequences. Mutation of miRNAs has been implicated in genetic hearing loss (Mencia et al., 2009; Solda et al., 2011). For example, a point mutation (G-to-A transition) at position 13 in one allele of miR-96 has been identified in a family with progressive postlingual hearing loss by mapping of an autosomal dominant deafness locus (DFNA50 (Mencia et al., 2009). Further screening of miR-96 mutations in a large number of families with NSHL has revealed three additional nucleotide substitutions in miR-96 that cause NSHL. One of the variants (+14 C>A) appears in the proband of a family segregating with DFNA50 hearing loss (Mencia et al., 2009). Importantly, these mutations, as demonstrated in a cell culture study, affect miRNA processing (Mencia et al., 2009). These observations link miR-96 mutations to genetic hearing loss. Further evidence for miR-96 involvement in genetic hearing loss includes the finding of progressive hearing loss and malformation of inner ear structures in a mouse model generated by ENU-induced miR-96 mutation (Kuhn et al., 2011; Lewis et al., 2009). While the identification of miR-96 mutations as a potential cause of NSHL is important, these miR-96 mutations may not be a common cause of NSHL as a recent investigation did not find any mutations in the miRs-183, -182 and -96 in 150 autosomal-dominant non-syndromic deafness families (Hildebrand et al., 2010).

Similar to miRNA mutations, mutations in target genes can also interrupt the interaction between miRNAs and their target mRNAs. To investigate the effect of mutations in a predicted miRNA binding site in the target genes related to NSHL on miRNA function, Hildebrand and colleagues (Hildebrand et al., 2010) screened the predicted binding sites of miRs-182 and -96 in the 3’UTR of the RDX gene, a radixin protein coding gene that has been linked to DFNB24 autosomal recessive NSHL. Among the 192 Iranian families segregating with autosomal recessive NSHL, mutation in the predicted binding sites for miRs-182 and -96 (c.*95C>A) was found in one family. However, a subsequent in vitro observation of the inhibitory effect of miRs-182 and -96 on RDX target gene expression did not reveal any effect of miRNA targeting on RDX gene expression. This suggests that miRs-182 and -96 do not play a direct role in NSHL through the associated RDX mutation. Further screening of the miRNA binding sites in additional predicted target genes in families with autosomal dominant and recessive non-syndromic deafness did not identify any potential deafness-causing mutations. Thus far, the link between the miR-183 cluster and known mutations in NSHL has not been firmly established. A comprehensive screening of mutations in the miRNA binding sites of other deafness-related genes is needed, so that the miRNA involvement in NSHL can be further assessed.

6. miRNAs and Hair Cell Regeneration

It is well known that sensory cells in the mammalian cochlea are unable to regenerate once they are lost. However, inner ear tissue in non-mammalian vertebrates, such as birds, reptiles and fish, has the ability to regenerate sensory cells after injury. This leads to the possibility that by studying regenerative mechanisms in lower vertebrate species, we will be able to identify the biological processes responsible for proliferation and differentiation of cells and be able to use this knowledge to initiate hair cell regeneration in mammalian ears.

Differential expression changes in miRNAs have been documented in cultured labyrinths comprising the auditory and vestibular sensory epithelia from the newt following gentamicin treatment (Tsonis et al., 2007). Importantly, these changes occur on a time frame consistent with the early phases of regeneration, raising the possibility that miRNAs participate in the molecular regulation of regeneration.

Bioinformatic analysis of gene expression profiling data identified miR-181a as a candidate regulator of regeneration in the basilar papilla from 0-day-old chicks treated with forskolin (Frucht et al., 2010), an adenylyl cyclase activator that promotes the proliferation of supporting cells, leading to the growth of new hair cells (Montcouquiol et al., 2001; Navaratnam et al., 1996; Szonyi et al., 1999). Further functional analysis showed that overexpression of miR-181a enhances the proliferation of basilar papilla cells and some of these newly produced cells are positive for myosin VI, a hair cell marker (Frucht et al., 2010). Conversely, inhibition of miR-181a reduces cell proliferation (Frucht et al., 2011), suggesting that miR-181a participates in the regulation of cell proliferation. This observation is important because it implicates miR-181a in auditory cell regeneration. Thus far, it is not clear how miR-181a regulates regeneration. Future investigation into the interaction between miR-181a and its mRNA targets may provide new insight into the molecular mechanisms associated with the regulatory role of miR-181a during regeneration.

Therapies for human hair cell regeneration are still considered a significant challenge due to the inability of hair cells to regenerate. More recently, stem cells have been genetically manipulated to generate cells with hair cell-like phenotypes (Li et al., 2003; Qin et al., 2011; Rivolta et al., 2006). One challenge with this approach is how to regulate the proliferation and differentiation of cells once they are reprogrammed and undergoing differentiation. This is where miRNAs may play an important role by initiating cellular differentiation, maintaining the process of differentiation, and terminating differentiation when required. To date, hundreds of miRNAs have been identified in cultured cochlear progenitor cells with varying expression patterns in undifferentiated and differentiated cells (Hei et al., 2011). However, the role of each miRNA involved in the differentiation of cochlear cells is not known. Understanding the regulatory roles of miRNAs may provide insight into hair cell regeneration in the mammalian inner ear.

7. miRNA Expression in the Inner Ear under Stress

Recent studies have analyzed the expression profiles of miRNAs in the organ of Corti under various pathological conditions, including oxidative insults, ototoxicity and noise-induced cochlear damage (Wang et al., 2010b; Yu et al., 2010). It is widely accepted that oxidative stress generated during various pathological insults can cause hair cell degeneration (Henderson et al., 2006; Jiang et al., 2007; Kovacic et al., 2008). However, the regulation of this degenerative process is not clear. A recent study by Wang and colleagues revealed miRNA expression changes in cultured inner ear derived cells under oxidative stress (Wang et al., 2010b) with 35 miRNAs being upregulated and 40 miRNAs being downregulated. These changes were accompanied by the transcriptional upregulation of 2076 mRNAs and the downregulation of 580 mRNAs. Target analysis revealed a correlation between target mRNAs and associated miRNA gene expression changes. Although the actual role of the identified miRNAs needs to be investigated and confirmed, the study implicates miRNAs in cellular responses to oxidative stress.

In an ototoxicity model induced by kanamycin treatment, the inner ear exhibits an increase in the expression of miRs-34a and -34c with a dose-dependent expression change for miR-34a (Yu et al., 2010). Both miRNAs target the p53 gene, which is a tumor suppressor gene involved in regulating apoptosis (Amaral et al., 2010; Lee et al., 1994; Oren, 1994). Therefore, these miRNAs may be involved in regulating cell damage and apoptosis (Rokhlin et al., 2008; Wong et al., 2011; Yamakuchi et al., 2009; Yamakuchi et al., 2008). Similar to ototoxicity, noise-induced cochlear damage involves apoptotic cell death (Hu et al., 2000; Nicotera et al., 2003). In a recent investigation into the involvement of miRNAs in acoustic trauma, Patel and colleagues (our unpublished data) screened 375 miRNAs in noise-traumatized cochlear sensory epithelia of rats and found differential expression changes in multiple miRNAs. including miRs-10a, -30d, -30e, -99b, -107, -124, -130b, -146b, -183, -186, -190b, -194, -200c, -325, -331, -333, -339, -381, -429, -532-3p and -674. Target analysis revealed that many of the altered miRNAs are related to genes that participate in regulating apoptosis. Thus far, the actual role of each of these altered miRNAs in sensory cell pathogenesis is still unknown. Because of the large number of candidate genes identified, the core challenge now is to prioritize future investigations so that the key players in sensory cell damage can be identified. To this end, a combination of large scale screening of genes, bioinformatic analysis of identified candidates and gain- or loss-of-function investigations have been employed. Understanding how miRNAs regulate cellular damage may offer novel therapeutic targets for preventing stress associated disorders in the inner ear.

8. Summary

From these studies, it is evident that miRNAs play a functional role in ear biology during development, regeneration and disease. While miRNA research has advanced rapidly, questions and challenges remain. First, only a small group of miRNA families have been identified in the ear, and many more remain to be identified. It is crucial to understand how miRNAs are processed in the inner ear and to identify which factors are responsible for regulation of miRNA transcription. Second, the inner ear contains heterogeneous cell populations, so it is necessary to identify miRNAs within specific cell types to understand the correlation between cell function and miRNA expression. Using a combination of ear dissection, cell isolation, and, deep sequencing techniques, this may be possible in the near future. Third, although increasing numbers of miRNAs are being identified, the molecular mechanisms of miRNA function in the inner ear remain unclear. To this end, high throughput mRNA expression profiling for identification of miRNA targets and bioinformatic analysis using target prediction algorithms may contribute toward revealing a clear picture of miRNA targeting pathways. Moreover, comprehensive loss-of-function and gain-of-function studies of inner ear miRNAs in various animal models can facilitate the understanding of miRNA/mRNA interactions. In conclusion, although there are challenges, miRNA research in ear biology opens a new avenue for discovery of new regulatory networks in normal and diseased tissues along with novel strategies for disease diagnosis, prevention, and treatment.

Research Highlights.

MicroRNAs play a critical role in regulating the developmental process of the inner ear.

MicroRNAs are associated with progressive hearing loss in humans.

MicroRNAs participate in the regulatory process of hair cell differentiation during regeneration.

MicroRNAs play a role in regulating cellular responses to inner ear stress.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Donald Coling for his helpful comments and suggestions. The research was supported by NIDCD1R01 DC010154-01 to BH Hu.

Abbreviations

- miRNA

microRNA

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- C.elegans

Caenorhabditis elegans

- UTR

untranslated region

- DGCR8

DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 8

- pre-miRNA

precursor miRNA

- Ran-GTP

Ran-guanoside triphosphate

- TRBP

trans-activation response RNA-binding protein

- eiFs

eukaryotic translation-initiation factors

- ENU

N-ethyl-N-nitrosurea

- DAVID

the database for annotation, visualization and integrated discovery

- NSHL

non-syndromic sensorineural hearing loss

- DFNA50

autosomal dominant deafness locus

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Minal Patel, Email: minalpat@buffalo.edu.

Bo Hua Hu, Email: bhu@buffalo.edu.

References

- Ajay SS, Athey BD, Lee I. Unified translation repression mechanism for microRNAs and upstream AUGs. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:155. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral JD, Xavier JM, Steer CJ, Rodrigues CM. The role of p53 in apoptosis. Discov Med. 2010;9:145–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambros V, Bartel B, Bartel DP, Burge CB, Carrington JC, Chen X, Dreyfuss G, Eddy SR, Griffiths-Jones S, Marshall M, Matzke M, Ruvkun G, Tuschl T. A uniform system for microRNA annotation. RNA. 2003;9:277–9. doi: 10.1261/rna.2183803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E, Kim SY, Carmell MA, Murchison EP, Alcorn H, Li MZ, Mills AA, Elledge SJ, Anderson KV, Hannon GJ. Dicer is essential for mouse development. Nat Genet. 2003;35:215–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohne BA, Yohman L, Gruner MM. Cochlear damage following interrupted exposure to high-frequency noise. Hear Res. 1987;29:251–64. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(87)90172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke J, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM. Principles of microRNA-target recognition. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e85. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, Hagedorn CH, Cullen BR. Human microRNAs are processed from capped, polyadenylated transcripts that can also function as mRNAs. RNA. 2004;10:1957–66. doi: 10.1261/rna.7135204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie M, Horvitz HR, Sulston JE. Mutations that lead to reiterations in the cell lineages of C. elegans. Cell. 1981;24:59–69. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90501-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chendrimada TP, Gregory RI, Kumaraswamy E, Norman J, Cooch N, Nishikura K, Shiekhattar R. TRBP recruits the Dicer complex to Ago2 for microRNA processing and gene silencing. Nature. 2005;436:740–4. doi: 10.1038/nature03868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabdoub A, Puligilla C, Jones JM, Fritzsch B, Cheah KS, Pevny LH, Kelley MW. Sox2 signaling in prosensory domain specification and subsequent hair cell differentiation in the developing cochlea. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18396–401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808175105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djuranovic S, Nahvi A, Green R. A parsimonious model for gene regulation by miRNAs. Science. 2011;331:550–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1191138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doench JG, Sharp PA. Specificity of microRNA target selection in translational repression. Genes Dev. 2004;18:504–11. doi: 10.1101/gad.1184404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt S, Szostak E, Yang Z, Pillai R. Artificial tethering of Argonaute proteins for studying their role in translational repression of target mRNAs. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;725:191–206. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-046-1_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkan-Miller T, Ulitsky I, Hertzano R, Rudnicki A, Dror AA, Lenz DR, Elkon R, Irmler M, Beckers J, Shamir R, Avraham KB. Integration of transcriptomics, proteomics, and microRNA analyses reveals novel microRNA regulation of targets in the mammalian inner ear. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels BM, Hutvagner G. Principles and effects of microRNA-mediated post-transcriptional gene regulation. Oncogene. 2006;25:6163–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulalio A, Huntzinger E, Izaurralde E. GW182 interaction with Argonaute is essential for miRNA-mediated translational repression and mRNA decay. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:346–53. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farh KK, Grimson A, Jan C, Lewis BP, Johnston WK, Lim LP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. The widespread impact of mammalian MicroRNAs on mRNA repression and evolution. Science. 2005;310:1817–21. doi: 10.1126/science.1121158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fechter LD, Liu Y, Pearce TA. Cochlear protection from carbon monoxide exposure by free radical blockers in the guinea pig. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1997;142:47–55. doi: 10.1006/taap.1996.8027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forge A, Schacht J. Aminoglycoside antibiotics. Audiol Neurootol. 2000;5:3–22. doi: 10.1159/000013861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman LM, Avraham KB. MicroRNAs and epigenetic regulation in the mammalian inner ear: implications for deafness. Mamm Genome. 2009a;20:581–603. doi: 10.1007/s00335-009-9230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman LM, Dror AA, Mor E, Tenne T, Toren G, Satoh T, Biesemeier DJ, Shomron N, Fekete DM, Hornstein E, Avraham KB. MicroRNAs are essential for development and function of inner ear hair cells in vertebrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009b;106:7915–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812446106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frucht CS, Santos-Sacchi J, Navaratnam DS. MicroRNA181a plays a key role in hair cell regeneration in the avian auditory epithelium. Neurosci Lett. 2011;493:44–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frucht CS, Uduman M, Duke JL, Kleinstein SH, Santos-Sacchi J, Navaratnam DS. Gene expression analysis of forskolin treated basilar papillae identifies microRNA181a as a mediator of proliferation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantier MP, McCoy CE, Rusinova I, Saulep D, Wang D, Xu D, Irving AT, Behlke MA, Hertzog PJ, Mackay F, Williams BR. Analysis of microRNA turnover in mammalian cells following Dicer1 ablation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:5692–703. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraldez AJ, Cinalli RM, Glasner ME, Enright AJ, Thomson JM, Baskerville S, Hammond SM, Bartel DP, Schier AF. MicroRNAs regulate brain morphogenesis in zebrafish. Science. 2005;308:833–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1109020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grun D, Wang YL, Langenberger D, Gunsalus KC, Rajewsky N. microRNA target predictions across seven Drosophila species and comparison to mammalian targets. PLoS Comput Biol. 2005;1:e13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu P, Reid JG, Gao X, Shaw CA, Creighton C, Tran PL, Zhou X, Drabek RB, Steffen DL, Hoang DM, Weiss MK, Naghavi AO, El-daye J, Khan MF, Legge GB, Wheeler DA, Gibbs RA, Miller JN, Cooney AJ, Gunaratne PH. Novel microRNA candidates and miRNA-mRNA pairs in embryonic stem (ES) cells. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu S, Jin L, Zhang F, Huang Y, Grimm D, Rossi JJ, Kay MA. Thermodynamic stability of small hairpin RNAs highly influences the loading process of different mammalian Argonautes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9208–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018023108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Lee Y, Yeom KH, Kim YK, Jin H, Kim VN. The Drosha-DGCR8 complex in primary microRNA processing. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3016–27. doi: 10.1101/gad.1262504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hei R, Chen J, Qiao L, Li X, Mao X, Qiu J, Qu J. Dynamic changes in microRNA expression during differentiation of rat cochlear progenitor cells in vitro. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson D, Bielefeld EC, Harris KC, Hu BH. The role of oxidative stress in noise-induced hearing loss. Ear Hear. 2006;27:1–19. doi: 10.1097/01.aud.0000191942.36672.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzano R, Elkon R, Kurima K, Morrisson A, Chan SL, Sallin M, Biedlingmaier A, Darling DS, Griffith AJ, Eisenman DJ, Strome SE. Cell type-specific transcriptome analysis reveals a major role for Zeb1 and miR-200b in mouse inner ear morphogenesis. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand MS, Witmer PD, Xu S, Newton SS, Kahrizi K, Najmabadi H, Valle D, Smith RJ. miRNA mutations are not a common cause of deafness. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:646–52. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgert N, Smith RJ, Van Camp G. Function and expression pattern of nonsyndromic deafness genes. Curr Mol Med. 2009;9:546–64. doi: 10.2174/156652409788488775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu BH, Henderson D, Nicotera TM. Involvement of apoptosis in progression of cochlear lesion following exposure to intense noise. Hear Res. 2002;166:62–71. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu BH, Guo W, Wang PY, Henderson D, Jiang SC. Intense noise-induced apoptosis in hair cells of guinea pig cochleae. Acta Otolaryngol. 2000;120:19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntzinger E, Izaurralde E. Gene silencing by microRNAs: contributions of translational repression and mRNA decay. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:99–110. doi: 10.1038/nrg2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isik M, Korswagen HC, Berezikov E. Expression patterns of intronic microRNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Silence. 2010;1:5. doi: 10.1186/1758-907X-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki S, Tomari Y. Argonaute-mediated translational repression (and activation) Fly (Austin) 2009;3:204–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Talaska AE, Schacht J, Sha SH. Oxidative imbalance in the aging inner ear. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:1605–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapsimali M, Kloosterman WP, de Bruijn E, Rosa F, Plasterk RH, Wilson SW. MicroRNAs show a wide diversity of expression profiles in the developing and mature central nervous system. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R173. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-8-r173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley MW. Cellular commitment and differentiation in the organ of Corti. Int J Dev Biol. 2007;51:571–83. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072388mk. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersigo J, D’Angelo A, Gray BD, Soukup GA, Fritzsch B. The role of sensory organs and the forebrain for the development of the craniofacial shape as revealed by Foxg1-cre-mediated microRNA loss. Genesis. 2011;49:326–41. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopecky B, Fritzsch B. Regeneration of Hair Cells: Making Sense of All the Noise. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2011;4:848–879. doi: 10.3390/ph4060848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koscianska E, Starega-Roslan J, Krzyzosiak WJ. The role of Dicer protein partners in the processing of microRNA precursors. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacic P, Somanathan R. Ototoxicity and noise trauma: electron transfer, reactive oxygen species, cell signaling, electrical effects, and protection by antioxidants: practical medical aspects. Med Hypotheses. 2008;70:914–23. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2007.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krek A, Grun D, Poy MN, Wolf R, Rosenberg L, Epstein EJ, MacMenamin P, da Piedade I, Gunsalus KC, Stoffel M, Rajewsky N. Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat Genet. 2005;37:495–500. doi: 10.1038/ng1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krol J, Loedige I, Filipowicz W. The widespread regulation of microRNA biogenesis, function and decay. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:597–610. doi: 10.1038/nrg2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn S, Johnson SL, Furness DN, Chen J, Ingham N, Hilton JM, Steffes G, Lewis MA, Zampini V, Hackney CM, Masetto S, Holley MC, Steel KP, Marcotti W. miR-96 regulates the progression of differentiation in mammalian cochlear inner and outer hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:2355–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016646108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara Y, Watanabe Y. Processing of miRNA precursors. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;592:231–41. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-005-2_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lall S, Grun D, Krek A, Chen K, Wang YL, Dewey CN, Sood P, Colombo T, Bray N, Macmenamin P, Kao HL, Gunsalus KC, Pachter L, Piano F, Rajewsky N. A genome-wide map of conserved microRNA targets in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2006;16:460–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Ajay SS, Yook JI, Kim HS, Hong SH, Kim NH, Dhanasekaran SM, Chinnaiyan AM, Athey BD. New class of microRNA targets containing simultaneous 5’-UTR and 3’-UTR interaction sites. Genome Res. 2009;19:1175–83. doi: 10.1101/gr.089367.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JM, Abrahamson JL, Bernstein A. DNA damage, oncogenesis and the p53 tumour-suppressor gene. Mutat Res. 1994;307:573–81. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(94)90267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–54. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Kim M, Han J, Yeom KH, Lee S, Baek SH, Kim VN. MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 2004;23:4051–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Ahn C, Han J, Choi H, Kim J, Yim J, Lee J, Provost P, Radmark O, Kim S, Kim VN. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature. 2003;425:415–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Steel KP. MicroRNAs in mouse development and disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21:774–80. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Quint E, Glazier AM, Fuchs H, De Angelis MH, Langford C, van Dongen S, Abreu-Goodger C, Piipari M, Redshaw N, Dalmay T, Moreno-Pelayo MA, Enright AJ, Steel KP. An ENU-induced mutation of miR-96 associated with progressive hearing loss in mice. Nat Genet. 2009;41:614–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Fekete DM. MicroRNAs in hair cell development and deafness. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010a;18:459–65. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e32833e0601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Kloosterman W, Fekete DM. MicroRNA-183 family members regulate sensorineural fates in the inner ear. J Neurosci. 2010b;30:3254–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4948-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Roblin G, Liu H, Heller S. Generation of hair cells by stepwise differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13495–500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2334503100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long D, Chan CY, Ding Y. Analysis of microRNA-target interactions by a target structure based hybridization model. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2008:64–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long D, Lee R, Williams P, Chan CY, Ambros V, Ding Y. Potent effect of target structure on microRNA function. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:287–94. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytle JR, Yario TA, Steitz JA. Target mRNAs are repressed as efficiently by microRNA-binding sites in the 5’ UTR as in the 3’ UTR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:9667–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703820104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdieh N, Rabbani B, Wiley S, Akbari MT, Zeinali S. Genetic causes of nonsyndromic hearing loss in Iran in comparison with other populations. J Hum Genet. 2010;55:639–48. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2010.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathonnet G, Fabian MR, Svitkin YV, Parsyan A, Huck L, Murata T, Biffo S, Merrick WC, Darzynkiewicz E, Pillai RS, Filipowicz W, Duchaine TF, Sonenberg N. MicroRNA inhibition of translation initiation in vitro by targeting the cap-binding complex eIF4F. Science. 2007;317:1764–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1146067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matranga C, Tomari Y, Shin C, Bartel DP, Zamore PD. Passenger-strand cleavage facilitates assembly of siRNA into Ago2-containing RNAi enzyme complexes. Cell. 2005;123:607–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mencia A, Modamio-Hoybjor S, Redshaw N, Morin M, Mayo-Merino F, Olavarrieta L, Aguirre LA, del Castillo I, Steel KP, Dalmay T, Moreno F, Moreno-Pelayo MA. Mutations in the seed region of human miR-96 are responsible for nonsyndromic progressive hearing loss. Nat Genet. 2009;41:609–13. doi: 10.1038/ng.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min H, Yoon S. Got target? Computational methods for microRNA target prediction and their extension. Exp Mol Med. 2010;42:233–44. doi: 10.3858/emm.2010.42.4.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montcouquiol M, Corwin JT. Brief treatments with forskolin enhance s-phase entry in balance epithelia from the ears of rats. J Neurosci. 2001;21:974–82. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-03-00974.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozova O, Hirst M, Marra MA. Applications of new sequencing technologies for transcriptome analysis. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2009;10:135–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082908-145957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods. 2008;5:621–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaratnam DS, Su HS, Scott SP, Oberholtzer JC. Proliferation in the auditory receptor epithelium mediated by a cyclic AMP-dependent signaling pathway. Nat Med. 1996;2:1136–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1096-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicotera TM, Hu BH, Henderson D. The caspase pathway in noise-induced apoptosis of the chinchilla cochlea. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2003;4:466–77. doi: 10.1007/s10162-002-3038-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen CB, Shomron N, Sandberg R, Hornstein E, Kitzman J, Burge CB. Determinants of targeting by endogenous and exogenous microRNAs and siRNAs. RNA. 2007;13:1894–910. doi: 10.1261/rna.768207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura K, Ishizuka A, Siomi H, Siomi MC. Distinct roles for Argonaute proteins in small RNA-directed RNA cleavage pathways. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1655–66. doi: 10.1101/gad.1210204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olena AF, Patton JG. Genomic organization of microRNAs. J Cell Physiol. 2010;222:540–5. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren M. Relationship of p53 to the control of apoptotic cell death. Semin Cancer Biol. 1994;5:221–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos GL, Reczko M, Simossis VA, Sethupathy P, Hatzigeorgiou AG. The database of experimentally supported targets: a functional update of TarBase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D155–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquinelli AE, Reinhart BJ, Slack F, Martindale MQ, Kuroda MI, Maller B, Hayward DC, Ball EE, Degnan B, Muller P, Spring J, Srinivasan A, Fishman M, Finnerty J, Corbo J, Levine M, Leahy P, Davidson E, Ruvkun G. Conservation of the sequence and temporal expression of let-7 heterochronic regulatory RNA. Nature. 2000;408:86–9. doi: 10.1038/35040556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai RS, Bhattacharyya SN, Filipowicz W. Repression of protein synthesis by miRNAs: how many mechanisms? Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:118–26. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin H, Zhao LD, Sun JH, Ren LL, Guo WW, Liu HZ, Zhai SQ, Yang SM. The differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into inner ear hair cell-like cells in vitro. Acta Otolaryngol. 2011;131:1136–41. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2011.603135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand TA, Ginalski K, Grishin NV, Wang X. Biochemical identification of Argonaute 2 as the sole protein required for RNA-induced silencing complex activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:14385–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405913101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand TA, Petersen S, Du F, Wang X. Argonaute2 cleaves the anti-guide strand of siRNA during RISC activation. Cell. 2005;123:621–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehmsmeier M, Steffen P, Hochsmann M, Giegerich R. Fast and effective prediction of microRNA/target duplexes. RNA. 2004;10:1507–17. doi: 10.1261/rna.5248604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remenyi J, Hunter CJ, Cole C, Ando H, Impey S, Monk CE, Martin KJ, Barton GJ, Hutvagner G, Arthur JS. Regulation of the miR-212/132 locus by MSK1 and CREB in response to neurotrophins. Biochem J. 2010;428:281–91. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivolta MN, Li H, Heller S. Generation of inner ear cell types from embryonic stem cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;330:71–92. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-036-7:71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokhlin OW, Scheinker VS, Taghiyev AF, Bumcrot D, Glover RA, Cohen MB. MicroRNA-34 mediates AR-dependent p53-induced apoptosis in prostate cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1288–96. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.8.6284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan DG, Oliveira-Fernandes M, Lavker RM. MicroRNAs of the mammalian eye display distinct and overlapping tissue specificity. Mol Vis. 2006;12:1175–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacheli R, Nguyen L, Borgs L, Vandenbosch R, Bodson M, Lefebvre P, Malgrange B. Expression patterns of miR-96, miR-182 and miR-183 in the development inner ear. Gene Expr Patterns. 2009;9:364–70. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha SH, Taylor R, Forge A, Schacht J. Differential vulnerability of basal and apical hair cells is based on intrinsic susceptibility to free radicals. Hear Res. 2001;155:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(01)00224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solda G, Robusto M, Primignani P, Castorina P, Benzoni E, Cesarani A, Ambrosetti U, Asselta R, Duga S. A novel mutation within the MIR96 gene causes non-syndromic inherited hearing loss in an Italian family by altering pre-miRNA processing. Hum Mol Genet. 2011 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontheimer EJ, Carthew RW. Molecular biology. Argonaute journeys into the heart of RISC. Science. 2004;305:1409–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1103076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soukup GA. Little but loud: small RNAs have a resounding affect on ear development. Brain Res. 2009;1277:104–14. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soukup GA, Fritzsch B, Pierce ML, Weston MD, Jahan I, McManus MT, Harfe BD. Residual microRNA expression dictates the extent of inner ear development in conditional Dicer knockout mice. Dev Biol. 2009;328:328–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston JE, Horvitz HR. Abnormal cell lineages in mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1981;82:41–55. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90427-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szonyi M, He DZ, Ribari O, Sziklai I, Dallos P. Cyclic GMP and outer hair cell electromotility. Hear Res. 1999;137:29–42. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M, Lieberman J, Lal A. Desperately seeking microRNA targets. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1169–74. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsonis PA, Call MK, Grogg MW, Sartor MA, Taylor RR, Forge A, Fyffe R, Goldenberg R, Cowper-Sal-lari R, Tomlinson CR. MicroRNAs and regeneration: Let-7 members as potential regulators of dedifferentiation in lens and inner ear hair cell regeneration of the adult newt. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;362:940–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valencia-Sanchez MA, Liu J, Hannon GJ, Parker R. Control of translation and mRNA degradation by miRNAs and siRNAs. Genes Dev. 2006;20:515–24. doi: 10.1101/gad.1399806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vella MC, Slack FJ. C. elegans microRNAs. WormBook. 2005:1–9. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.26.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters RW, Bradrick SS, Gromeier M. Poly(A)-binding protein modulates mRNA susceptibility to cap-dependent miRNA-mediated repression. RNA. 2010;16:239–50. doi: 10.1261/rna.1795410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Doench JG, Novina CD. Analysis of microRNA effector functions in vitro. Methods. 2007;43:91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XR, Zhang XM, Zhen J, Zhang PX, Xu G, Jiang H. MicroRNA expression in the embryonic mouse inner ear. Neuroreport. 2010a;21:611–7. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328338864b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Liu Y, Han N, Chen X, Yu W, Zhang W, Zou F. Profiles of oxidative stress-related microRNA and mRNA expression in auditory cells. Brain Res. 2010b;1346:14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston MD, Pierce ML, Rocha-Sanchez S, Beisel KW, Soukup GA. MicroRNA gene expression in the mouse inner ear. Brain Res. 2006;1111:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston MD, Pierce ML, Jensen-Smith HC, Fritzsch B, Rocha-Sanchez S, Beisel KW, Soukup GA. MicroRNA-183 family expression in hair cell development and requirement of microRNAs for hair cell maintenance and survival. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:808–19. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wienholds E, Kloosterman WP, Miska E, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Berezikov E, de Bruijn E, Horvitz HR, Kauppinen S, Plasterk RH. MicroRNA expression in zebrafish embryonic development. Science. 2005;309:310–1. doi: 10.1126/science.1114519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkos TM, Koscianska E, Krzyzosiak WJ. Practical Aspects of microRNA Target Prediction. Curr Mol Med. 2011;11:93–109. doi: 10.2174/156652411794859250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MY, Yu Y, Walsh WR, Yang JL. microRNA-34 family and treatment of cancers with mutant or wild-type p53 (Review) Int J Oncol. 2011;38:1189–95. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia W, Cao G, Shao N. Progress in miRNA target prediction and identification. Sci China C Life Sci. 2009;52:1123–30. doi: 10.1007/s11427-009-0159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S, Witmer PD, Lumayag S, Kovacs B, Valle D. MicroRNA (miRNA) transcriptome of mouse retina and identification of a sensory organ-specific miRNA cluster. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25053–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700501200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakuchi M, Lowenstein CJ. MiR-34, SIRT1 and p53: the feedback loop. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:712–5. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.5.7753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakuchi M, Ferlito M, Lowenstein CJ. miR-34a repression of SIRT1 regulates apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13421–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801613105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan D, Liu XZ. Cochlear molecules and hereditary deafness. Front Biosci. 2008;13:4972–83. doi: 10.2741/3056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Tang H, Jiang XH, Tsang LL, Chung YW, Chan HC. Involvement of calpain-I and microRNA34 in kanamycin-induced apoptosis of inner ear cells. Cell Biol Int. 2010;34:1219–25. doi: 10.1042/CBI20100515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]