Abstract

Objective

The aim was to examine statin discontinuation rates in a cohort of elderly Australians with newly diagnosed cancer using population-based secondary health data.

Design

Observational cohort study.

Setting

New South Wales, the largest jurisdiction in Australia. The Pharmaceutical Benefits and Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Schemes are national programmes subsidising prescription drugs to the Australian population and Australian Government Department of Veterans' Affairs clients.

Participants

The cohort comprised 1731 cancer patients aged ≥65 years with evidence of statin use in the 90 days prior to diagnosis. They were matched to 3462 non-cancer patients prescribed statins in the same period.

Main outcome measure

The authors compared statin discontinuation rates up to 4 years post-diagnosis and examined the factors associated with statin discontinuation.

Results

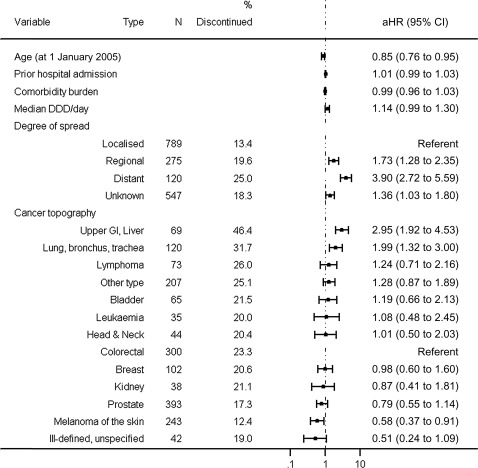

The proportion of cancer patients discontinuing statin therapy at 4 years (27%) was comparable to the comparison cohort; however, significantly higher proportions of the cancer cohort discontinued statins than the comparison cohort at 3, 6 and 12 months of follow-up (9.7% vs 7.4% at 12 months, respectively). More than 30% of cancer patients who died were dispensed statins within 30 days of death. Discontinuation of statin therapy in cancer patients was associated with regionalised and distant disease spread at diagnosis (p<0.001), older age (p=0.006), upper gastrointestinal organs and liver cancer (aHR 2.95, 95% CI 1.92 to 4.53) and cancer of the lung, bronchus and trachea (aHR 1.99, 95% CI 1.32 to 3.00) and poorer survival.

Conclusions

Medications should be rationalised at the time of a cancer diagnosis, especially in the setting of a poor prognosis. At least for some patients in our cohort, statin therapy may be inappropriately continued which adds unnecessarily to therapeutic burden.

Article summary

Article focus

There is limited clinical guidance on managing comorbid conditions after the diagnosis of life-threatening illness.

Some medications may be continued unnecessarily and may even cause harm after a cancer diagnosis.

The aim of this study is to examine the rates of statin discontinuation in a cohort of older cancer patients compared with their peers with no cancer diagnosis.

Key messages

In the setting of cancer, statins may be continued unnecessarily in some patients.

A high proportion of cancer patients are dispensed statins 30 days before death.

Reassessment of existing treatments is recommended after a cancer diagnosis so as to minimised therapeutic burden.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is a large retrospective cohort study of elderly Australians using population data set linkage.

We were unable to establish if statin therapy had been reviewed subsequent to a cancer diagnosis nor the reasons for discontinuation.

Introduction

There has been much debate about the clinical and economic benefits of prescribing preventive medicines for patients with life-limiting illness.1–3 In the area of cancer, there has been a particular focus on ‘futile’ drug use in the setting of advanced disease where median survival is relatively short and there is little to no evidence demonstrating the benefits of drug treatments during anticipated survival times.2 4–6 Consequently, there have been calls from the medical community to review and reduce the therapeutic burden on patients with life-threatening disease.4–7

Despite the large body of evidence guiding clinicians to initiate medications for the management of comorbid conditions, there has been limited guidance on reducing or ceasing medications at the end of life. Furthermore, there is a scarcity of studies examining the management of comorbid conditions after the diagnosis of life-threatening illness. However, there is some evidence to suggest that medications used for the secondary prevention of comorbid disease are continued longer than clinically indicated.1 5 8 9

Statins are among the most commonly prescribed medications in the developing world. Their benefit in reducing cardiovascular events and mortality after an acute coronary syndrome, as well as the reduction in risk of major cardiovascular events in people without established cardiovascular disease is well documented.10–13 However, many questions remain about the use of these medicines with advancing age. In particular, competing risks from cancer and other comorbid conditions, drug interactions due to high levels of polypharmacy and tolerability are likely to alter the benefit/risk ratios in older patients.14–16

The aim of this study was to examine statin discontinuation in a cohort of elderly cancer patients as compared with a matched cohort of non-cancer patients. We also assess the predictors of statin discontinuation in cancer patients, including the effect of spread of disease.

Methods

Setting

The Pharmaceutical Benefits and Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Schemes (PBS and RPBS) are national programmes subsidising prescription drugs to the Australian population and Australian Government Department of Veterans' Affairs (DVA) clients. The RPBS comprises all PBS items plus additional items available only to DVA clients.17 18 In the Australian setting, chronic medicines including statins are generally prescribed as a month supply with five repeats.19

Data sources and linkage

We used the following data sets to undertake our study:

DVA client file (1994–2007): information on sex, dates of birth and death and veteran entitlement level of DVA clients residing in New South Wales (NSW), the largest Australian state.

RPBS (July 2004 to June 2009): all dispensed pharmaceutical items (RPBS item code, name and strength, date of supply, quantity supplied and entitlement at time of dispensing).

NSW Central Cancer Registry (1994–2007): mandatory notifications of invasive cancer in NSW. We used International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third edition (ICD-O-3)20 codes to identify cancer types.

Admitted Patient Data Collection (July 2000 to June 2009): all public, private and repatriation hospital separations in NSW.

Data linkage was undertaken by the NSW Centre for Health Record Linkage using best practice privacy preserving protocols. The study was approved by the NSW Population and Health Services and Department of Veterans' Affairs Human Research Ethics Committees (approval numbers: 2008/02/060 and E008/003) and did not require consent from individuals.

Cancer cohort (n=1731)

Comprised fully entitled clients aged 65 years or older, with a primary invasive cancer notification between 2005 and 2007, alive for at least 6 months post-diagnosis and with at least two statin dispensing records (ATC codes C10AA, C10BA, C10BX) in the 90 days prior to their diagnosis date (at least one within 60 days). We used the statin dispensing date immediately prior to diagnosis date as the index date for follow-up.

Comparison cohort (n=3462)

Certain cancers are gender specific and age related.21 22 Furthermore, statin discontinuation is age and gender related by virtue of their relationship to cardiovascular risk factors.23 As such, we matched (using random selection without replacement) two clients with no evidence of a cancer notification to every cancer cohort member on year of birth (within 5 years), gender, a statin dispensing record within 15 days of the index date and first statin dispensing date (within 15 days) to match patients with comparable duration of statin treatment. Cohort members also were alive for at least 6 months after the index date.

Statistical analyses

Differences between the characteristics of the cohorts were examined using χ2 (likelihood ratio) test. Our follow-up period commenced 60 days after the index date until 31 December 2009. We defined the discontinuation date as the date of last dispensing plus 30 days. We did not consider patients to have discontinued therapy if this date was within 6 months of the end of follow-up or in the 3 months before death. We calculated proportion discontinued at various time-points using Kaplan–Meier product limit estimates. Kaplan–Meier overall survival curves were generated for cancer patients who did and did not discontinue statins in the first 6 months after diagnosis. Follow-up continued until the last statin dispensing date before discontinuation, 31 December 2009 or death date.

We used Cox regression to compare discontinuation between cohorts, stratifying by cancer patients matched to their controls (prior hospitalisation was included as a covariate due to difference between the cohorts after matching). For the cancer cohort, we also used Cox proportional hazard regression to determine the factors associated with discontinuation following a cancer diagnosis; adjusting for year of birth, spread of disease, cancer topography, hospitalisations prior to diagnosis, comorbidity burden and median statin daily quantity prior to diagnosis. We calculated the median daily quantity as ([Tablet Strength × Quantity dispensed]/WHO Defined Daily Dose (DDD)24)/days supplied] and comorbidity using the Rx-Risk Index using counts of up to 42 general drug categories (not including cancer drug categories) using pharmacy claims data within 6 months prior to a patient's cancer diagnosis.25 26 We omitted gender from this model as some cancers are gender specific. However, gender did not show a statistically significant bivariate association with discontinuation. Statistical significance was assessed at the p<0.05 (two-tailed) level.

Results

Cohort characteristics

Approximately two-thirds of the cancer and comparison cohorts were aged 75 years or older on 1 January 2005 and 72% were men. The most common cancer diagnoses were prostate (23%), colorectal (17%) and melanoma of the skin (14%). Most cancer patients were diagnosed with localised (46%) or unknown spread (32%). The cancer cohort had fewer hospital admissions in the year prior to the index date than the comparison cohort (92% of the cancer cohort with ≤4 separations; 84% in the comparison cohort; likelihood ratio χ2=85.6, p<0.0001). Comorbidity burden was similar in both cohorts with 78% having four to nine comorbidities prior to the index date.

Statin use prior to the index date

More than 90% of both cohorts were prescribed atorvastatin, simvastatin or pravastatin alone. The median daily quantity prior to the index date was at least 1 DDDs per day for atorvastatin, pravastatin and rovastatin. The median time between the first statin dispensing to the index date was approximately 600 days for both cohorts, with 18% of the cancer cohort and 26% of the comparison group having at least one period of at least 90 days between dispensing records; median duration of breaks in therapy were 136 and 142 days in the cancer and comparison cohorts, respectively (table 1).

Table 1.

Statin use prior to (and including) index date of cancer and comparison cohorts

| Variable | Cancer cohort | Comparison cohort |

| N=1731 | N=3462 | |

| Statin type, n (%) | ||

| Atorvastatin alone | 685 (39.6) | 1304 (37.8) |

| Fluvastatin alone | 13 (0.8) | 39 (1.1) |

| Pravastatin alone | 257 (14.8) | 525 (15.2) |

| Rosuvastatin alone | 1 (0.0) | 3 (0.0) |

| Simvastatin alone | 653 (37.7) | 1306 (37.8) |

| Two or more statins | 122 (7.0) | 285 (8.2) |

| DDD/day, median (IQR) | ||

| Atorvastatin | 1.00 (1.0–2.00) | 1.00 (1.00–2.00) |

| Fluvastatin | 0.67 (0.33–0.67) | 0.67 (0.33–0.67) |

| Pravastatin sodium | 1.33 (0.67–1.33) | 1.33 (0.67–1.33) |

| Rosuvastatin | 2.00 (1.00–2.00) | 2.00 (1.00–2.31) |

| Simvastatin | 0.67 (0.67–1.33) | 0.67 (0.67–1.33) |

| Time from first statin to index date (days), median (IQR) | 611 (336–901) | 616 (339–903) |

| Patients with breaks of ≥90 days in therapy, n (%) | 310 (17.9) | 888 (25.6) |

| Duration of breaks in therapy (days), median (IQR) | 136 (102–211) | 142 (104–232) |

DDD, defined daily dose.

Statin discontinuation

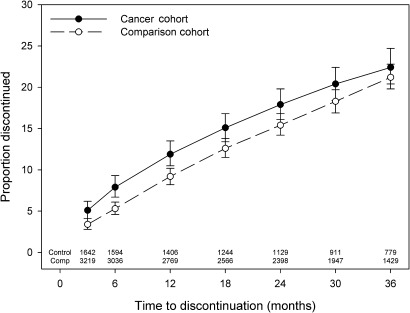

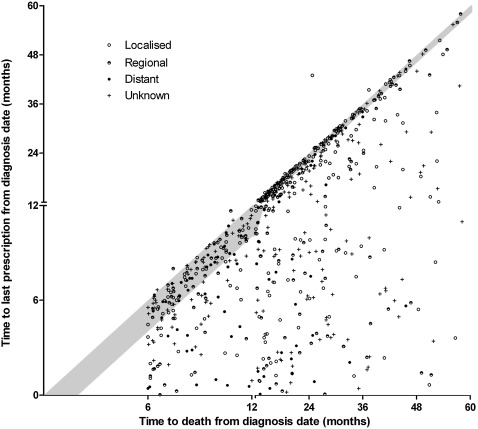

Median follow-up time was 913 and 958 days for the cancer and comparison cohorts, respectively (IQR 464–1297 and 496–1289 days). We found no significant differences in the discontinuation estimates of the cancer and comparison cohorts after 4 years (cancer 26.5% (95% CI 24.1% to 29.2%); comparison 27.2% (95% CI 25.3% to 29.1%), p=0.34 log-rank test). A significantly higher proportion of cancer patients compared with the comparison cohort discontinued statin therapy at 3, 6 and 12 months; however, after 12 months, the proportion of the cancer and comparison cohort discontinuing therapy was comparable (figure 1). More than 31% of the cancer cohort who died had a statin dispensed within 30 days of their death (figure 2), and this was the case for 21% of those with metastatic disease and 35% with localised spread at diagnosis.

Figure 1.

Statin discontinuation after index date as determined with Kaplein–Meier product limit estimates.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot of time to last statin prescription against time to death from diagnosis date. Shaded area indicates the period within 30 days of death.

Predictors of statin discontinuation

Cancer patients did not have significantly different time to statin discontinuation when compared with their matched comparisons or was prior hospitalisation a significant factor (stratified Cox proportional hazard regression: p=0.56 and p=0.96, respectively). For the cancer cohort alone, older age and those diagnosed with non-localised disease had shorter time to statin discontinuation, as did patients with upper gastrointestinal and liver cancer and cancer of the lung, bronchus and trachea. Patients with melanoma of the skin had longer times to discontinuation (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Adjusted* Cox proportional hazard regression analyses for association with statin discontinuation during follow-up for cancer cohort (*adjusted for all factors in the table).

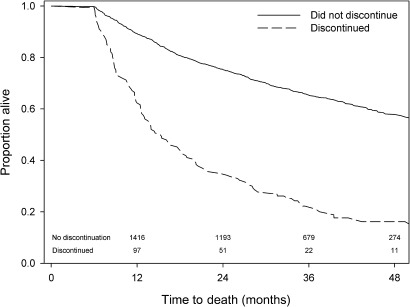

Figure 4 further demonstrates the relationship between statin discontinuation and prognosis; cancer patients who had discontinued statin therapy within 6 months of diagnosis had poorer overall survival than those who did not discontinue statin therapy within 6 months (log-rank p value <0.001).

Figure 4.

Overall survival for cancer patients who survived 6 months from diagnosis and who did and did not discontinue statin therapy within that time.

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study of elderly Australians highlights a need for comprehensive and ongoing review of medications after the diagnosis of life-limiting illness. Our findings demonstrate that in the setting of cancer, statins may be continued unnecessarily. We chose to examine statins as they are only used for risk reduction and the decision they should be discontinued when the prognosis is poor is relatively straightforward. It is likely that the variation in the practice observed in our study of reconsidering medication use at the time of diagnosis would be similar to that of other medications. In fact, when the indication is less clear-cut, discontinuation may be less likely to occur.

To complement the existing literature, which has focused on statin discontinuation in the 6 months prior to death, we examined statin discontinuation subsequent to a cancer diagnosis and found the proportion of patients discontinuing therapy are relatively low in the first 12 months after a diagnosis but are higher than in non-cancer patients. Beyond 12 months post-diagnosis discontinuation, estimates were no different to those in the non-cancer population and when compared with each matched control, there was no difference between cancer and non-cancer populations for time to discontinuation.

Research in this area to date has focused exclusively on cancer patients with end-stage diseases.1 5 6 However, our methodological approach using a cohort of patients diagnosed at all stages of disease demonstrates clearly that there may be some recognition on the part of doctors and/or patients that medications need to be rationalised in light of a poorer prognosis. In our cohort, statin discontinuation was associated with a diagnosis of metastatic disease and poorer overall survival. Nevertheless, a large proportion of cancer patients were prescribed statins in the 30 days before death.

Our findings are consistent with previous research from North America and Australia, all of which highlight the missed opportunities to reduce the therapeutic burden of many patients after a life-limiting diagnosis.4–7 If the potential benefits of therapy are incremental and long term, then there are strong imperatives for review when cancer therapies are commenced as it is well established that the risks of adverse outcomes increases exponentially with the total number of medications (the ‘therapeutic burden’).27 Our study is limited in that we were unable to establish the reasons for discontinuation in our cohort. However, improved communication among physicians and patients is likely to increase the understanding about the original therapeutic goals of particular treatments. Furthermore, more systematic guidance on ceasing medications at the end of life would reduce therapeutic burden for individual patients and have the added benefit of reducing costs placed on already stretched healthcare budgets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This article has been reviewed by DVA prior to publication and the views expressed are not necessarily those of the Australian Government.

Footnotes

To cite: Stavrou EP, Buckley N, Olivier J, et al. Discontinuation of statin therapy in older people: does a cancer diagnosis make a difference? An observational cohort study using data linkage. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000880. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000880

Contributors: EPS (research fellow cancer epidemiology, University of New South Wales (UNSW)); NB (professor of medicine, UNSW); JO (senior biostatistician, UNSW); S-AP (A/Prof and Head Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmaceutical Policy Research Group, University of Sydney). EPS performed the statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript; JO guided the statistical analyses; NB and S-AP designed the study and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. S-AP is guarantor. All authors had full access to all the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: This study was funded by a Cancer Australia project grant (ID number: 568773). S-AP is a Cancer Institute NSW Career Development Fellow (ID number: 09/CDF/2-37).

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: We were provided data access with a waive of patient consent so as to undertake whole of population analyses.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by NSW Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional unpublished data available for this study.

References

- 1.Hall P, Lord S, El-Laboudi A, et al. Non-cancer medications for patients with incurable cancer: time to stop and think. Br J Gen Pract 2010;60:243–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanvetyanon T, Choudhury A. Physician practice in the discontinuation of statins among patients with advanced lung cancer. J Palliat Care 2006;22:281–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stevenson JP, Currow D, Abernathy A, et al. The broader implications of managing statins at the end of life. J Palliat Care 2007;23:188–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riechelmann R, Krzyzanowska MK, Zimmermann C. Futile medication use in terminally ill cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2009;17:745–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fede A, Miranda M, Antonangelo D, et al. Use of unnecessary medications by patients with advanced cancer: cross-sectional survey. Support Care Cancer 2011;19:1313–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silveira M, Segnini Kazanis A, Shevrin M. Statins in the last six months of life: a recognizable, life-limiting condition does not decrease their use. J Palliat Med 2008;11:685–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vollrath A, Sinclair C, Hallenbeck J. Discontinuing cardiovascular medications at the end of life: lipid-lowering agents. J Palliat Med 2005;8:876–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abernathy A, Aziz N, Basch E, et al. A strategy to advance the evidence base in palliative medicine: formation of a palliative care research cooperative group. J Palliat Med 2010;13:1407–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis G. Discontinuing lipid-lowering agents. J Palliat Med 2006;9:619–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amarenco P, Labreuche J, Lavallee P, et al. Statins in stroke prevention and carotid atherosclerosis: systematic review and up-to-date meta-analysis. Stroke 2002;35:2902–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sever P, Dahlof B, Poulter N, et al. Prevention of coronary and stroke events with atorvastatin in hypertensive patients who have average or lower-than-average cholesterol concentrations, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial—Lipid Lowering Arm (ASCOT-LLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2003;361:1149–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shepherd J, Blauw GJ, Murphy MB, et al. Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002;360:1623–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Downs JR, Clearfield M, Weis S, et al. Primary prevention of acute coronary events with lovastatin in men and women with average cholesterol levels: results of AFCAPS/TexCAPS. Air Force/Texas Coronary Atheroscelrosis Prevention Study. JAMA 1998;279:1615–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ballantyne C, Corsini A, Davidson M, et al. Risk for myopathy with statin therapy in high-risk patients. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:553–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corsini A, Bellosta S, Baetta R, et al. New insights into the pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties of statins. Pharmacol Ther 1999;84:413–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newman C, Palmer G, Silbershatz H, et al. Safety of atorvastatin derived from analysis of 44 completed trials in 9,416 patients. Am J Cardiol 2003;92:670–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Department of Veterans' Affairs (DVA) Annual Report 2006-2007. Canberra: DVA, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Veterans' Affairs Rehabilitation RaDG Treatment Population Statistics. Quarterly Report September 2007. Canberra: Department of Veretans' Affairs, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rossi S, ed. The Australian Medicines Handbook (AMH). 12th edn Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Percy C, Van Holten V, Muir C, eds. ICD-O International Classifi Cation of Diseases for Oncology. 3rd edn Geneva: WHO, 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 21.AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) & AACR (Australasian Association of Cancer Registries) Cancer in Australia: An Overview, 2008. Cancer Series No. 46. Cat No. CAN 42. Canberra: AIHW, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tracey E, Kerr T, Dobrovic A, et al. Cancer in NSW: Incidence and Mortality Report 2008. Sydney: Cancer Institute NSW, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Latry P, Molimard M, Dedieu B, et al. Adherence with statins in a real-life setting is better when associated cardiovascular risk factors increase: a cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2011;11:46 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2261/11/46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology ATC/DDD Index: C10AA HMG CoA Reductase Inhibitors. Oslo: World Health Organization, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu CY, Barratt J, Vitry A, et al. Charlson and Rx-risk comorbidity indices were predictive of mortality in the Australian health care setting. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:223–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vitry A, Wong SA, Roughead EE, et al. Validity of medication-based co-morbidity indicies in the Australian elderly population. Aust N Z J Public Health 2009;33:126–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maggiore RJ, Gross CP, Hurria A. Polypharmacy in older adults with cancer. Oncologist 2010;15:507–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.