Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the trends and correlations of gross domestic product (GDP) adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP) per capita on suicide rates in 10 WHO regions during the past 30 years.

Design

Analyses of databases of PPP-adjusted GDP per capita and suicide rates. Countries were grouped according to the Global Burden of Disease regional classification system.

Data sources

World Bank's official website and WHO's mortality database.

Statistical analyses

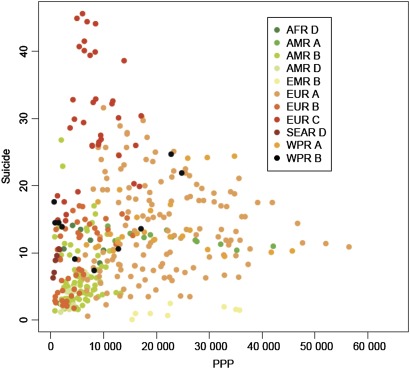

After graphically displaying PPP-adjusted GDP per capita and suicide rates, mixed effect models were used for representing and analysing clustered data.

Results

Three different groups of countries, based on the correlation between the PPP-adjusted GDP per capita and suicide rates, are reported: (1) positive correlation: developing (lower middle and upper middle income) Latin-American and Caribbean countries, developing countries in the South East Asian Region including India, some countries in the Western Pacific Region (such as China and South Korea) and high-income Asian countries, including Japan; (2) negative correlation: high-income and developing European countries, Canada, Australia and New Zealand and (3) no correlation was found in an African country.

Conclusions

PPP-adjusted GDP per capita may offer a simple measure for designing the type of preventive interventions aimed at lowering suicide rates that can be used across countries. Public health interventions might be more suitable for developing countries. In high-income countries, however, preventive measures based on the medical model might prove more useful.

Article summary

Article focus

Describe the geographical variability of suicide rates worldwide during the past 30 years.

Examine the trends in GDP per capita adjusted for PPP per capita and suicide rates.

Investigate the correlation between PPP-adjusted GDP per capita and suicide rates in 10 WHO regions during the past 30 years.

Key messages

A country's economic growth, measured by PPP-adjusted GDP per capita, is not invariably followed by a decrease in suicide rates. If economic growth is not accompanied by adequate infrastructures for mental health services, suicide rates might trend up.

PPP-adjusted GDP per capita strongly correlates to suicide rates worldwide, and the direction and magnitude of the correlation differs between developing and developed countries.

PPP-adjusted GDP per capita offers a simple measure to help decide the type of preventive measure that is more suitable across countries: public health interventions might be more suitable for developing countries, whereas preventive measures directed towards psychiatric disorders might be the right choice in high-income countries.

Strengths and limitations of this study

WHO subregions were used as the units of analysis, and aggregation bias is typical of studies that collapse different countries into single categories.

Several socioeconomic factors that operate at the individual level—microsocioeconomic factors—(eg, gender, unemployment, divorce rate, urban/rural ratio, alcohol use, etc) might have a confounding effect and mediate trends in suicide rates.

Major strengths of the present study are the longitudinal design, which allowed us to analyse trends, and the use of PPP-adjusted GDP per capita, one of the fairest and simplest measures of living standards.

Suicide rates have increased dramatically over the past 45 years despite prevention efforts.1 There is marked geographic variability in suicide rates, with the highest rates being found in Eastern Europe and the lowest in Muslim and Latin American countries.1 2 So far, this variability in suicide rates has not been satisfactorily explained.2

The majority of studies in the psychiatric literature have approached the analysis of risk factors and correlates of suicidal behaviours from a clinical perspective in developed countries.3 In these countries, clinical studies definitively establish that psychiatric disorders are a major contributing factor to suicide.1 3 It is not completely clear how well these studies can be extrapolated to the general population because psychiatric disorders are relatively uncommon in the general population and the majority of subjects diagnosed as having a mental disorder do not complete suicide.3 4 The impact of psychiatric risk factors on suicide rates differs significantly depending on socioeconomic status in Western developed countries and, more importantly, this impact may be much smaller in developing countries.3

Morselli5 and Durkheim6 were the first authors to point towards the socioeconomic driving forces operating on the changing suicide rates. Since their seminal 19th century studies, suicide has usually been considered a social problem,2 and several risk factors have been related to suicidal behaviour, both at the subject level (microsocioeconomic factors) and at the state level (macrosocioeconomic level).7 Recently, Innamorati et al8 reported, consistently with previous research, significant associations between suicide rates and several macrosocioeconomic factors.8 Both high basal levels of income and elevated economic growth have been found to be associated with reduced suicide rates.9 10 Suicide rates are lower in Western high-income countries compared with low- and middle-income countries.10 In addition, the global change in economic activities that has taken place over the past 60 years has deeply affected people's emotional health and may have influenced suicide rates.11 Gross domestic product (GDP), a measure of economic activity, has been negatively correlated with suicide rates, suggesting that suicide rates drop in times of economic expansion11 and increase in times of recession.12 In recent times, Luo et al13 suggested that business cycles affect suicide rates in the USA: the overall suicide rate usually rises during recessions and falls during expansions. Similarly, the Asian economic crisis has been linked with steep increases in suicide rates in some, but not all, East/Southeast Asian countries.14

It has been suggested that the relationship between GDP per capita and suicide may follow an inverted U-shaped curve, with suicide trends declining after peaking at a certain threshold of economic development.15 Thus, although at low GDP levels, increases in GDP are associated with increases in suicide rates, once a given threshold of economic development is reached, further increases in GDP do not correlate with further increases in suicide rates. The threshold at which the inverted U-shaped curve starts trending down may vary depending on several social, economic and cultural differences across countries. On the other hand, some authors have suggested that, compared with GDP, more complex constructs such as ‘National Intelligence’ or the ‘K factor’—including measures of national IQ; gross national product; life expectancy; birthrates; infant mortality; HIV/AIDS and of rape, serious assault and homicide—may better explain the geographic variability of suicide rates.16

In the present study, we examined the trends in GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP) and suicide rates and investigated the correlation between PPP-adjusted GDP per capita and suicide rates in 10 WHO regions during the past 30 years. The present study extends previous research by including all available information worldwide, thus allowing refinement and clarification of the regional differences that may explain the relationship between economic cycles, as measured by PPP-adjusted GDP per capita, and suicide rates.

Methods

Data collection

We collected data on annual PPP-adjusted GDP per capita for 210 countries for the period 1980–2007 from the World Bank's official website (http://www.worldbank.org/). GDP per capita is a basic measure of a country's overall economic activity and development.15 PPP-adjusted GDP per capita adjusts the cost of living to the income level of each country and is a better measure of living standards of a given country than nominal GDP.17 WHO countries were grouped by regions based on the Global Burden of Disease regional classification system (available at http://www.who.int/choice/demography/regions/en/). All countries are classified into the following geographic subregions: African region, AFR; Eastern Mediterranean region, EMR; European region, EUR; region of the Americas, AMR; Southeast Asia region, SEAR; and Western Pacific Region, WPR. They were also classified by mortality strata: A, very low child, very low adult; B, low child, low adult; C, low child, high adult; D, high child, high adult and E, high child, very high adult).

Suicide statistics and population data for 56 countries were extracted from the latest WHO mortality database for the period 1980–2007.18 Cross-national data on suicide rates did not form a regular time series, that is, the time intervals were irregular. Thus, for instance, the gap between the years for which suicide rate data are available is sometimes 3, sometimes 5 or 6 years. We only included in our analyses those countries where statistics of suicide rates were available for a minimum of 6 years—the median and mode of the number of years with statistics of suicide rates was six—namely, AFR D (Mauritius); AMR A (Canada and the USA); AMR B (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Mexico, Panama, St. Lucia, Trinidad and Tobago and Venezuela); AMR D (Ecuador and Guatemala); EUR A (Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK); EUR B (Bulgaria, Georgia, Macedonia, Poland, Romania and the Slovak Republic); EUR C (Estonia, Hungary, Latvia and Lithuania); SEAR D (India); WPR A (Australia, New Zealand, Japan and Singapore) and WPR B (China and South Korea).

Statistical analyses

After graphically displaying the trends for PPP-adjusted GDP per capita and suicide rates over the study period (see figure 1, supplementary material), correlations within regions were carried out to explore whether changes in GDP were associated with changes in suicide rates (see figures 2 and 3, supplementary material). To test for significance of the correlations within regions, an analysis of variance for each WHO region was calculated.19 20 The Bonferroni method was used to correct for multiple testing.

Mixed effect models are appropriate for representing and analysing clustered, and therefore dependent, data. In each analysis of variance, PPP-adjusted GDP per capita was treated as a fixed factor and individual countries within each region as random effects, with suicide rate that differs only in an (random) additive term or a (random) slope from the other countries in the cluster. This allows us to draw conclusions on the cluster level. Data analyses and graphics were performed using SPSS for Mac-version 17 (SPSS Inc.) and R (http://www.r-project.org).

Results

Descriptive analyses

Figure 1 (Supplementary material) shows the annual PPP-adjusted GDP per capita and suicide rates in each WHO region for the last 30 years. PPP-adjusted GDP per capita has increased over the last 3 decades in all regions. As for suicide rates, they have increased over the last 3 decades in developing Latin American and Caribbean countries (AMR B) and some WPR A countries (high-income Asian countries, such as Japan and South Korea). On the other hand, suicide rates have decreased over the last 3 decades in the majority of European countries and Canada. Finally, suicide rates have followed an inverted U shape over the last 3 decades in EUR C countries, such as Hungary and Latvia.

Figure 1.

Correlations between purchasing power parity-adjusted gross domestic product and rate of suicide per 100 000 (WHO).

Effect of PPP-adjusted GDP per capita on suicide rates

The results of the mixed effect models are displayed in table 1. With the exception of the African countries, there was a significant impact of PPP-adjusted GDP on suicide rates in all WHO subregions analysed (AFR D; F=0.42, p=0.55).

Table 1.

Mixed effect models

| WHO region | F | df | p Value | r | 95% CI |

| AFR D | |||||

| Model | 21.86 | 2 | 0.003 | ||

| PPP | 0.42 | 1 | 0.546 | 0.278 | 0.213 to 0.339 |

| Country | 6.03 | 1 | 0.058 | ||

| AMR A | |||||

| Model | 5541.93 | 3 | <0.001 | ||

| PPP | 37.60 | 1 | <0.001 | −0.801 | −0.789 to −0.813 |

| Country | 1040.71 | 2 | <0.001 | ||

| AMR B | |||||

| Model | 34.91 | 16 | <0.001 | ||

| PPP | 11.48 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.371 | 0.347 to 0.393 |

| Country | 13.61 | 15 | <0.001 | ||

| AMR D | |||||

| Model | 144.25 | 3 | <0.001 | ||

| PPP | 21.69 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.814 | 0.763 to 0.855 |

| Country | 10.94 | 2 | 0.002 | ||

| EUR A | |||||

| Model | 465.48 | 24 | <0.001 | ||

| PPP | 85.26 | 1 | <0.001 | −0.473 | −0.358 to −0.510 |

| Country | 141.67 | 23 | <0.001 | ||

| EUR B | |||||

| Model | 502.38 | 10 | <0.001 | ||

| PPP | 14.48 | 1 | <0.001 | −0.404 | −0.367 to −0.479 |

| Country | 120.14 | 9 | <0.001 | ||

| EUR C | |||||

| Model | 630.64 | 8 | <0.001 | ||

| PPP | 155.07 | 1 | <0.001 | −0.837 | −0.788 to −0.844 |

| Country | 198.00 | 7 | <0.001 | ||

| SEAR D | |||||

| Model | 724.01 | 2 | <0.001 | ||

| PPP | 16.73 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.763 | 0.754 to 0.771 |

| Country | 94.66 | 1 | <0.001 | ||

| WPR A | |||||

| Model | 523.74 | 5 | <0.001 | ||

| PPP | 0.69 | 1 | 0.041 | −0.120 | −0.110 to −0.132 |

| Country | 102.47 | 4 | <0.001 | ||

| WPR B | |||||

| Model | 132.36 | 3 | <0.001 | ||

| PPP | 28.66 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.872 | 0.858 to 0.886 |

| Country | 81.92 | 2 | <0.001 | ||

PPP, purchasing power parity.

Figure 1 graphically shows the correlation between PPP-adjusted GDP and each region. The linear correlations between PPP-adjusted GDP per capita and suicide rates in each country within each region are displayed in supplementary figures 2 and 3. The magnitude of the correlations is shown in table 1. We found three distinct groups of countries based on the correlation between the GDP per capita and suicide rates: (1) positive correlation—developing (lower middle and upper middle income) Latin-American and Caribbean countries (AMR B and AMR D; r=0.371, p=0.001 and r=0.814, p=0.001, respectively); developing Southeast Asian countries (SEAR D; r=0.763, p=0.001), including India, and some countries in the Western Pacific Region (WPR B; r=0.872, p<0.001) such as China and South Korea and Japan; (2) negative correlation—high-income European countries (EUR A; r=−0.473, p<0.001); developing (lower-middle and upper-middle income) European regions (EUR B and C; r=−0.404, p<0.001 and r=−0.837, p<0.001, respectively); AMR A countries (r=−0.801, p<0.001), especially Canada, and some WPR A countries, such as Australia and New Zealand and (3) no correlation was found in AFR D (r=0.278, p=0.546).

Discussion

In the present study, we examined worldwide trends and correlations of PPP-adjusted GDP per capita and suicide rates in 10 WHO subregions during the past 30 years. PPP-adjusted GDP increased over the study period in all regions examined with the exception of the EUR C countries. Suicide rates increased in developing Latin American and Caribbean countries (AMR B) and high-income Asian countries (WPR A), while they decreased in most European countries and Canada. Our findings are partially consistent with the reports linking suicide rates with GDP measures8 11 12 but extend them by refining the direction of the correlation between suicide rates and GDP depending on the overall trends of economic expansion versus recession and distinguishing between developed and developing countries. Our study suggests that a country's economic growth, measured by PPP-adjusted GDP per capita, is not invariably followed by a decrease in suicide rates. Interestingly, this is exactly what Morselli5 reported back in 1882. Of note, most of the countries in which we found a negative correlation between GDP per capita and suicide rates are developed countries (European countries, USA, Canada, New Zealand and Australia) in which the PPP-adjusted GDP per capita has been trending up during the period analysed. Conversely, most of the countries in which we found a positive correlation are developing Latin American and Caribbean countries in which the GDP per capita has also been trending up during the period analysed, but a positive correlation was also found in high-income economies such as Japan and South Korea. This is partially consistent with suggestions that suicide is a different phenomenon in developed and developing countries.3 10 In addition, our results showed that the relationship between PPP-adjusted GDP per capita and suicide rates is fairly stable across time worldwide. In other words, our study does not support the hypothesis that there is a lagged effect between economic cycles, as measured by PPP-adjusted GDP per capita and suicide rates. Taken together, our data may suggest that if economic growth is not accompanied by adequate infrastructures for mental health services, suicide rates might trend up.21 This is supported by a study reporting that elevated economic growth and high basal levels of income reduce suicide rates, whereas income inequality causes them to increase.9 In another recent study, public expenditure on health as a percentage of total government expenditures was one of the strongest predictors of suicide rates in the European Union.8 Lack of access to healthcare, particularly psychiatric care, appears to be a contributing factor to suicide risk in the USA.2 Even in the developed world, it takes a long time to develop health infrastructures and to show decreases in inequalities and healthcare progress in primary care settings.22 Characteristically, the development of mental health services is neglected as compared with overall health, particularly in developing countries.23 Thus, even if short-term suicide prevention measures can be useful during economic crisis,13 policy makers and mental health administrators should allocate resources, particularly during economic expansions, allowing for the rapid development of mental health services.23 This strategy might prove more useful in reducing suicide rates worldwide in the long run compared with ad hoc prevention plans.

Negative correlation between PPP-adjusted GDP per capita and suicide rates

The negative correlation between PPP-adjusted GDP per capita and suicide rates in both developing and developed European countries might be explained not only by economic development but by the implementation of national mental health policies and infrastructures21 and the perception of social integration of European citizens. In this regard, a negative correlation between the number of practicing General Practitioners, a measure of healthcare resources, and suicide rates was reported in Hungary.24 The healthcare systems of the 27 European Union member states are diverse. However, virtually all European countries have regulated universal healthcare.25 The convergence of high living standards and the fight against social exclusion have been major concerns of the European Union since the early 1990s. Sufficient income, employment, health, social and familial support are important factors for social inclusion, and the bulk of European societies perceive themselves to be socially integrated.26 In Canada, even if mental health is unequally distributed across socio-economic levels, the universal healthcare system is closer to the public health systems in European countries than to the US health system.27 Australia is a high-income country with one of the highest standards of health development worldwide. The Australian health system is broadly considered as one of the most effective and efficient worldwide; this system is a complex mixture of private and public health and includes a broad range of regulatory mechanisms and funding.28 In the case of New Zealand, the universal provision of free care was implemented since its very beginning as a nation and includes Māori minorities.29

Positive correlation between PPP-adjusted GDP per capita and suicide rates

The positive correlation between PPP-adjusted GDP per capita and suicide rates found in Latin American and Caribbean countries can be explained by several factors. First of all, suicide rates in Latin American and Caribbean countries are particularly low, even when compared with southern European countries. Religion, strong socio-familial ties and the fact that these countries may not be reporting reliable statistics may help explain their low suicide rates. Low- and medium-income countries are less likely to have a mental health policy21 that might serve an ‘umbrella-like’ function when living standards are improving. Clinical services and mental health infrastructures are typically poor in low- and middle-income countries. Most of the Latin American and Caribbean countries in which we found a positive correlation between PPP-adjusted GDP per capita and suicide rates are currently upper-middle-income economies.30 Economic growth might be related to precarious labour market conditions, interpersonal distrust, social exclusion and economic and health inequalities.31 Latin America is the subcontinent with the highest income inequality, with a high incidence of homicides and violence, unequal distribution of healthcare and social exclusion.32 In addition, in contrast to Europe, most Latin American and Caribbean countries lack a universal public healthcare system. The availability of mental health workers is very low compared with the USA and European countries.33

Suicide rates in India were also positively correlated with GDP rates. However, it should be noted that the quality of evidence used in mortality estimates for India is poor to fair (level 3 in WHO rating system). India estimates suicide rates based on a sample of the population. Moreover, suicide is illegal in India, so there is an even greater risk of under-reporting.34 It has been estimated that only about 25% of deaths in India are registered and only about 10% are medically certified.35 Comparisons of verbal autopsy studies of all deaths with the official suicide rate have shown that the suicide rate reported for this country is probably significantly lower than the actual rate.36 Therefore, the results regarding India should be interpreted with caution.21 As for Japan and South Korea, although after Bonferroni correction, results were no longer statistically significant, the particular characteristics of this world region deserve a comment on their own. Both countries are high-income economies characterised by universal health coverage. However, in contrast with other high-income countries where public health systems predominate, in both countries, the private health sector prevails over public health resources.37 38 Japan has the third largest economy in the world and one of the most equalitarian societies in the world. However, the reputation of Japan's healthcare quality has raised some concerns. Healthcare providers are mostly private and copayment is the rule. In addition, Japan is the fastest-ageing country in the world. Traditionally, older people were supported and looked after by their relatives. Recent societal changes, however, such as women entering the labour force, have made caring for elderly relatives difficult. The underdevelopment of home care in Japan raises concerns that ageing without family support increases the likelihood of suicide in older people.37 In addition, annual suicide rates have been correlated with the increase in the divorce rate, a social factor that negatively influences mental health.39 In recent times, life expectancy has rapidly increased in South Korea. However, mortality due to suicide increased, particularly among men aged 30 years or older.40 The authors suggested that suicide might be the price being paid for social disruption related to industrialisation.

Strengths and limitations

In the present study, whole WHO subregions were used as the units of analysis. Cross-level bias has been pointed out as a potential validity threat to such aggregate-level findings.16 Aggregation bias is typical of studies that collapse different countries into single categories.15 41 The effects observed on the aggregate level might be spurious and may not correspond to directionally consistent effects at the individual level.16 The result of factors related to suicide at the subject level can be modulated by the ecological context.42 In addition, several socioeconomic factors that operate at the individual level, such as gender, female labour force participation, unemployment, divorce rate, urban/rural ratio, religion and alcohol use, among others, might have a confounding effect and mediate trends in suicide rates. Furthermore, time series data are frequently non-stationary. Therefore, linear regression analyses of two data series might generate significant associations even if the series are independent.42 Finally, possible registration bias caused by differences in the requirements to register deaths by suicide between countries and over time must be taken into account.15

On the other hand, our study has several strengths. We analysed data from all available countries worldwide, grouped according to WHO subregions. Moreover, we obtained data for a period of almost 3 decades. The longitudinal design allowed us to analyse trends. A country's economic development is a long-standing process that requires a longitudinal design in order to be properly assessed.41Another strength is that we used PPP-adjusted GDP per capita, which is one of the fairest and simplest measures of living standards.

Conclusions

The present study shows that GDP is strongly correlated to suicide rates worldwide and that the direction and magnitude of the correlation differs between developing and developed countries.

Suicide is an extremely complex behaviour, and its conceptualisation as a single final pathway might be simplistic.43 Some authors have suggested that the suicide rate is more responsive to economic factors, such as real GDP per capita or growth rate of real GDP per capita, than to social factors, such as female labour participation or divorce rate.9 The results of the present study have important implications for public health and suicide prevention. The present study suggests that prevention strategies should be tailored to each WHO region. PPP-adjusted GDP per capita offers a simple measure to help decide the type of preventive measure that is more suitable across countries.10 In order to reduce population suicide rates, macroeconomic public health interventions—for example, the provision of basic needs, the reduction of socioeconomic inequalities—might be more suitable for developing countries where socioeconomic and cultural factors appear to play a major contributing role in suicide.3 10 In high-income countries, where the medical model prevails and suicide is understood as an unfortunate consequence of psychiatric illness—particularly depressive disorders3—preventive measures based on the medical model—for example, incrementing the number of psychiatric or counselling services—might prove more fruitful in helping to decrease the daunting suicide rates worldwide.1

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Lorraine Maw, MA, who helped in editing this article.

Footnotes

To cite: Blasco-Fontecilla H, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Garcia-Nieto R, et al. Worldwide impact of economic cycles on suicide trends over 3 decades: differences according to level of development. A mixed effect model study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000785. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000785

Contributors: All authors made substantial contributions to the final draft. HB-F conceived the article, downloaded data from public databases, retrieved all bibliography and wrote the initial draft. EB-G contributed to the conception and design of the initial draft. EB-G, PF-N and HG analysed and interpreted the data. PF-N was the sole author of the figure artwork. MP-R, RG-N and JdL drafted and revisited the article critically for intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of this draft.

Funding: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form. Dr. Blasco-Fontecilla acknowledges the Spanish Ministry of Health (Rio Hortega CMO8/00170; SAF2010-21849), Alicia Koplowitz Foundation and Conchita Rabago Foundation for funding his post-doctoral stage at CHRU, Montpellier, France. Apart from these, there are no other financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years, and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional unpublished data from the study.

References

- 1.Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, et al. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA 2005;294:2064–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tondo L, Albert MJ, Baldessarini RJ. Suicide rates in relation to health care access in the United States: an ecological study. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:517–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manoranjitham SD, Rajkumar AP, Thangadurai P, et al. Risk factors for suicide in rural south India. Br J Psychiatry 2010;196:26–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krysinska K, Martin G. The struggle to prevent and evaluate: application of population attributable risk and preventive fraction to suicide prevention research. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2009;39:548–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morselli E. Suicide: Essay on Comparative Moral Statistics. New York, NY: Appleton & Co, 1882 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durkheim E. Suicide. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1952 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lester D, Yang BJ. Microsocioeconomics versus macrosocioeconomics as a model for examining suicide. Psychol Rep 1991;69:735–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Innamorati M, Tamburello A, Lester D, et al. Inequalities in suicide rates in the European Union's elderly: trends and impact of macro-socioeconomic factors between 1980 and 2006. Can J Psychiatry 2010;55:229–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen J, Choi YJ, Sawada Y. How is Suicide Different in Japan? Japan: CIRJE Discussion Papers. 2008. http://www.e.u-tokyo.ac.jp/cirje/research/03research02dp.html [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacob KS. The prevention of suicide in India and the developing world: the need for population-based strategies. Crisis 2008;29:102–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ying YH, Chang K. A study of suicide and socioeconomic factors. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2009;39:214–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tapia Granados JA. Increasing mortality during the expansions of the US economy, 1900–1996. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34:1194–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo F, Florence CS, Quispe-Agnoli M, et al. Impact of business cycles on US suicide rates, 1928–2007. Am J Public Health 2011;101:1139–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang SS, Gunnell D, Sterne JA, et al. Was the economic crisis 1997–1998 responsible for rising suicide rates in East/Southeast Asia? A time-trend analysis for Japan, Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Thailand. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:1322–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moniruzzaman S, Andersson R. Economic development as a determinant of injury mortality—a longitudinal approach. Soc Sci Med 2008;66:1699–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voracek M. Suicide rates, national intelligence estimates, and differential K theory. Percept Mot Skills 2009;109:733–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor AM, Taylor MP. The Purchasing Power Parity Debate: NBER Working Paper No. 10607. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 18.WHO WHO Statistical Information System (WHOSIS). 2008. http://www.who/int/whosis/mort/download/en [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bland JM, Altman DG. Calculating correlation coefficients with repeated observations: Part 1—Correlation within subjects. BMJ 1995;310:446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bland JM, Altman DG. Calculating correlation coefficients with repeated observations: Part 2—Correlation between subjects. BMJ 1995;310:633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacob KS, Sharan P, Mirza I, et al. Mental health systems in countries: where are we now? Lancet 2007;370:1061–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher B, Neve H, Heritage Z. Community development, user involvement, and primary health care. BMJ 1999;318:749–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ngui EM, Khasakhala L, Ndetei D, et al. Mental disorders, health inequalities and ethics: a global perspective. Int Rev Psychiatry 2010;22:235–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szanto K, Kalmar S, Hendin H, et al. A suicide prevention program in a region with a very high suicide rate. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:914–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duncan B. Health policy in the European Union: how it's made and how to influence it. BMJ 2002;324:1027–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Böhnke P. Perceptions of social integration and exclusion in an enlarged Europe. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steele LS, Dewa CS, Lin E, et al. Education level, income level and mental health services use in Canada: associations and policy implications. Healthc Policy 2007;3:96–106 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Healy J, Sharman E, Lokuge B. Australia: Health System Review. Health Systems in Transition. Copenhagen: WHO. Regional Office for Europe on behalf of the European Observagtory on Health Systems and Policies, 2006. http://euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/96433/E89731.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 29.French S, Old A, Healy J. Health Care Systems in Transition: New Zealand. WHO (European Observatory on Health Care Systems), 2001. http://euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/95138/E74467.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 30.Country Groups. Washington: World Bank, 2010. http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications/country-and-lending-groups [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moyano Diaz E, Barría R. Suicidio y producto interno bruto (PIB) en Chile: Hacia un model predictivo. Rev Latin Psicol 2006;38:343–59 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Espinoza E, Barten F. Health reform in El Salvador: a lost opportunity for reducing health inequity and social exclusion? J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62:380–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alarcón RD, Aguilar-Gaxiola SA. Mental health policy developments in Latin America. Bull World Health Organ 2000;78:483–90 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soman CR, Safraj S, Kutty VR, et al. Suicide in South India: a community-based study in Kerala. Indian J Psychiatry 2009;51:261–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruzicka LT. Suicide in countries and areas of the ESCAP region. Asia Pac Popul J 1998;13:55–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Joseph A, Abraham S, Muliyil JP, et al. Evaluation of suicide rates in rural India using verbal autopsies, 1994–9. BMJ 2003;326:1121–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arai Y, Ikegami N. Health care systems in transition. II. Japan, Part I. An overview of the Japanese health care systems. J Public Health Med 1998;20:29–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shin Y. Health care systems in transition. II. Korea, Part I. An overview of health care systems in Korea. J Public Health Med 1998;20:41–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inoue K. Significant correlation of the change in the divorce rate with the suicide rate in Japan from 1992 to 2004. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2009;30:311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang S, Khang YH, Harper S, et al. Understanding the rapid increase in life expectancy in South Korea. Am J Public Health 2010;100:896–903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moniruzzaman S, Andersson R. Relationship between economic development and suicide mortality: a global cross-sectional analysis in an epidemiological transition perspective. Public Health 2004;118:346–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lucey S, Corcoran P, Keeley HS, et al. Socioeconomic change and suicide: a time-series study from the Republic of Ireland. Crisis 2005;26:90–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manoranjitham SD, Jayakaran R, Jacob KS. Suicide in India. Br J Psychiatry 2006;188:86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.