Abstract

Introduction

Individuals exposed to red blood cell alloantigens through transfusion, pregnancy or transplantation may produce antibodies against the alloantigens. Alloantibodies can pose serious clinical problems such as delayed haemolytic reactions and logistic problems, for example, to obtain timely and properly matched transfusion blood for patients in which new alloantibodies are detected.

Objective

The authors hypothesise that the particular clinical conditions (eg, used medication, concomitant infection, cellular immunity) during which transfusions are given may contribute to the risk of immunisation. The aim of this research was to examine the association between clinical, environmental and genetic characteristics of the recipient of erythrocyte transfusions and the risk against erythrocyte alloimmunisation during that transfusion episode.

Methods and analysis Study design

Incident case–cohort study.

Setting

Secondary care, nationwide study (within the Netherlands) including seven hospitals, from January 2005 to December 2011.

Study population

Consecutive red cell transfused patients at the study centres.

Inclusion

The study cohort comprises of consecutive red blood cell transfused patients at the study centre.

Exclusion

Patients with transfusions before the study period and/or pre-existing alloantibodies.Cases defined as first time alloantibody formers; Controls defined as transfused individuals matched (on number of transfusions) to cases and have not formed an alloantibody.

Statistical analysis

Logistic regression models will be used to assess the association between the risk to develop antibodies and potential risk factors, adjusted for other risk factors.

Ethics and dissemination

Approval at each local ethics regulatory committee will be obtained. Data will be coded for privacy reasons. Patients will be sent a letter and an information brochure explaining the purpose of the study. A consent form in presence of the study coordinator will be signed before the blood taking commences. Investigators will submit progress summary of the study to study sponsor regularly. Investigators will notify the accredited ethics board of the end of the study within a period of 8 weeks.

Article summary

Article focus

Identifying transfusion-related risk factors of alloimmunisation against red blood cell (RBC) antigens.

Identifying clinical risk factors of alloimmunisation against RBC antigens.

Identifying environmental and genetic risk factors of alloimmunisation against RBC antigens.

Key messages

Alloimmunisation against RBC transfusion is a clinically relevant problem faced by transfusion specialists.

Identifying a high-risk group of responders who form allantibodies against transfused RBCs would be the next step towards transfusion of complete phenotyped matched RBC.

In synergy with other ongoing studies, cost-effectiveness of a phenotyped matched RBC approach will be assessed.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Multicentre, matched case–cohort design.

Good representative sample of controls from large base cohort of general population.

Cases and controls matched on the number of RBC transfusions.

Possibility that patients entering cohort have had transfusions prior to start of study period in other hospitals/non-study centres.

Previous pregnancies in women could play a role in alloimmunisation. Retrospective data will not allow for a comprehensive check on previous pregnancies.

There could be a few cases selected who are booster/secondary alloimmune responders, instead of first time ever alloantibody formers.

Introduction

Individuals exposed to red blood cell (RBC) alloantigens through transfusion, pregnancy or transplantation may produce antibodies against the alloantigens expressed by RBCs. Although the incidence of these events is debated and ranges between the percentages of 1%–6% in single transfused and up to 30% in polytransfused patients (eg, sickle cell disease, thalassaemia and myelodysplasia),1 they can pose serious clinical problems such as delayed haemolytic reactions as well as logistic problems, for example, to obtain timely and properly matched transfusion blood for patients in which new alloantibodies are detected. Of course, prevention of alloimmunisation by extended matching between donors and all transfused patients (ie, on the basis of typing patients for the most relevant RBC antigens) would be an ultimate but complicated and costly solution. However, matching of donors only for patients who are defined to have a high alloimmunisation risk would be a more feasible step forward. This strategy would be especially valuable because as soon as immunisation for one antigen develops, additional immunisations tend to develop more frequently.2 3

Characterisation of patients and clinical conditions with high immunisation risk can be derived from studying the possible correlations between the actual immunisation and patient-related factors (both genetic and acquired) and/or transfusion-associated situations.

Such a study comparing immunised and non-immunised patients with a similar transfusion history will generate RR or relative protective factors.

We expect a twofold impact from our study: (1) to identify a set of transfusion recipients who need to be extensively matched and (2) to help understand the mechanisms underlying the development of alloantibodies to erythrocyte transfusion.

Rationale/background

Alloantibodies can lead to serious clinical consequences and logistic problems like obtaining properly and timely matched blood for the patients who do develop these antibodies. Prevention of such serious events is possible by extended matching and typing of donor's blood against the patient's for all the possible antigens, but this process is cumbersome and costly. Identifying a high-risk group will be a feasible first target and advanced matching a big step forward, and the aim of our study.

It is known that the recipient's formation of antibodies depends not only on dose and route of administration and the immunogenicity of the antigen but probably also on genetic or acquired patient-related factors. It has been shown that the number of transfusions also plays an important role in alloimmunisation against RBC, with the risk increasing with the increasing number of transfusions.4 It is generally recognised that immunocompromised patients have a lower risk to develop such antibodies.5 Relatively little is known, however, about other patient-related risk factors.2 3 6–9

A recent study examined such patient-related risk factors in a case–control study among 101 cases developing erythrocyte alloantibodies and 87 controls.10 In this two-centre study, patients with first time detected antibodies and at least one transfusion in the past were compared with controls with a negative antibody screening in the same centre. After adjustment for a limited number of confounders, this study confirmed known risk factors for antibody formation, such as female sex (increased risk, since women are more susceptible to exposure of alloantigens during pregnancy, miscarriages, abortions and childbirth11), lymphoproliferative disease and leukaemia (lower risk attributed to lymphocyte dysfunction by concomitant chemotherapy and suppression of the immune response12). Also new and partly unexpected risk factors were found, such as diabetes and solid tumours (both increased risk). Although the latter patients do undergo chemotherapy as well, in this group, antibodies might develop more easily because of their chronic inflammatory state.13 The limitations of this case–control study,10 however, were (1) the selection method for controls favoured controls that had received more transfusions with also smaller transfusion time intervals compared with the cases, (2) the relatively small number of patients reducing the detection of smaller RRs and (3) a relatively crude assessment of only a limited number of potential risk factors. Additionally, the study design did not allow investigating the association with the actual factors at the time of the likely primary immunisation/causal transfusion. We will not only try to confirm the observed potential risk factors in a larger cohort, but we aim to find other clinical, environmental as well as genetic factors. There is well-documented evidence that certain human leukocyte antigen (HLA) types are associated with enhanced response to RBC antigens like Kell, Duffy and Kidd.14–16 HLA genes in this respect are particularly interesting because along with their polymorphisms, they have been shown to play an active role in autoimmune disorders and diseases, which develop via T cell-mediated immunity.17 Moreover, several of these genes have been identified in human studies to be associated with susceptibility and resistance to mycobacterial infection. Another strong correlation was shown between immunodeficient genotype (interferon γ receptor 1 deficiency) and responsiveness to mycobacterium antigen.18 Finally, specific single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) associations have been identified to play a role in viral immunity and variations in both humeral and cellular immunity following measles vaccination.19 20 Although many genes are involved in the immune system, SNP's in genes (eg, coding for HLA types) that modulate specific and innate immune responses will be of the first targets in our analyses. We hypothesise that this will yield genetic modulators on the patients' humoural response to particular erythrocyte-expressed antigens but maybe even more broadly to other antigens as well.

By our questionnaire, we will query environmental, lifestyle factors and socioeconomic status as those have been suggested to modulate the immune response. Environmental factors such as exposure to helminthic, fungal and parasitic infections do play a role in modulating the general set point of the immune response at young age.21 The same is true for living in unsanitary conditions and for unhygienic occupations throughout life.22 Additional information on ‘immune modulating’ conditions during childhood and youth will be collected from the vaccination status, completion of the vaccination programme, presence of pet animals, place of residence (urban/rural) and visits to day care centres during childhood. The questionnaire will add to the knowledge to these possible confounders in cases and controls.

Research objective

The aim of the project was to examine the association between clinical, environmental and genetic characteristics of the recipient of erythrocyte transfusions and the risk of immunisation against erythrocyte alloantigens that he/she was exposed to during that transfusion episode.

Methodology

Study design and study population

We will perform a retrospective matched case–cohort study at hospitals nationwide from a period January 2005 to December 2011. Large RBC using hospitals will be selected as study bases. The study cohort will comprise of consecutive RBC transfused patients at the study centre.

Cases are defined as first time ever irregular RBC antibody formers, with no history of RBC transfusions and alloimmunisation before the study period.

Controls will be all consecutive transfused patients who had received their first and subsequent red blood transfusions at the study centre with no history of RBC transfusions and alloimmunisation.

Observational studies, if well conducted, are equipped to examine interesting transfusion research questions. With that in mind, we chose a case–cohort study design for our study. With the help of such a design, we can compare the cases occurring in a RBC transfused cohort with a randomly selected sample of the cohort. Using such an approach, for any one given case, we will select two controls that have had at least the same number or more transfusions than the case itself. This approach has following advantages:

This ensures that all the patients in the transfusion cohort with same or higher number of transfusions have an equal chance of being picked as controls. In essence, any member of the cohort who has been at a similar transfusion risk (of alloimmunisation) at some point in their transfusion history can be selected as a control.

Cases also have an equal chance of getting selected as controls for other cases.

This study design minimises the selection bias, if any. Such a study design allows us to include a number of patients, which is sufficient to detect smaller effects and to adjust for other risk factors, as well as to document potential risk factors extensively.

Matching

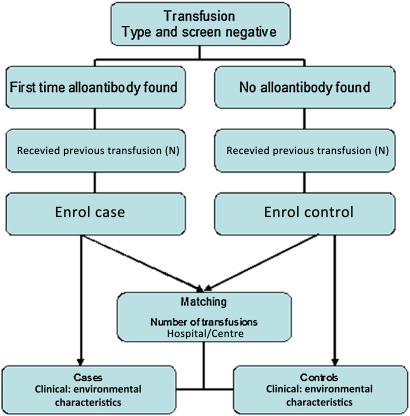

We will take into account the number of transfusions a particular case received until the antibody-forming episode and match the two cases (selected per control) on the same number of transfusions.

To account for interhospital differences nationwide, we will also match the cases and controls on the site/study centre (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study design for the matched control group.

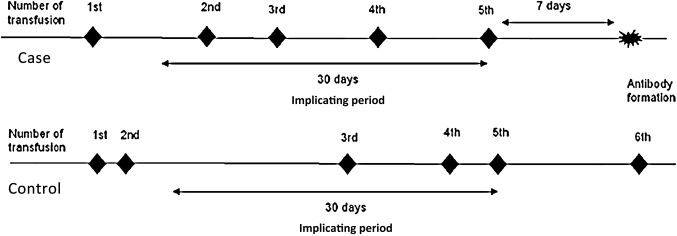

Implicated period

To examine the immunomodulating clinical risk factors surrounding the transfusions preceding the date of alloantibody formation, we will define a clinical risk period or an implicated period of alloimmunisation during which the case would have formed an irregular RBC antibody. This period would be the time (in days) between the date of a first ever positive screen for alloantibody to a calendar date 30 days before that positive screen. We will also introduce a lag period of minimum 7 days between that first ever positive screen and the last ever transfusion (implicating transfusion) before that positive screen (figure 2). This is to ensure that a patient's immune system has adequate time to respond to the transfusion exposure.

Figure 2.

Implicating period of clinical data collection.

We will define a similar implicated period in the matched controls as well, retrospectively from the implicating transfusion to 30 calendar days back (figure 2).

First time formed alloantibody

Our endpoint for cases, or first time formed irregular RBC antibodies is defined as clinically significant antibodies as screened by a three-cell serology panel at 37°C. All patients were routinely screened for alloantibodies, which is repeated at least every 72 h, if further transfusions as required. The antibodies are screened for by a three-cell panel, including an indirect antiglobulin test (LISS Diamed ID gel system, DiaMed-ID system, DiaMed, Murten, Switzerland) and subsequently identifies by a standard 11 cell panels in the same gel system.

Data acquirement, measurements and handling

Transfusion cohort data will be acquired from the hospital blood transfusion services and on-site patient records. Second, we will use data from a patient questionnaire. Third, we will determine the patients' racial background from blood of the included and consenting patients.

Patient medical history and records

Potential clinical risk factors include haematological, oncological, surgical and medicinal data as well as autoimmune diseases and related conditions at the time of the implicated (likely causal) transfusion. Factors and conditions that will be actively scored are: infections (including the causal microorganisms) and active/chronic allergies (including the if known antigens), fever, cytopenia(s), systemic inflammatory response (a clinical response to a (non)-specific insult of either infectious or non-infectious origin), peripheral blood progenitor cells transplantation (autologous or allogenous), multitrauma, splenectomy, solid malignancies, autoimmune disorders (rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus type 1, etc), chemotherapy, immunosuppressive drugs, cytostatics and antibiotics will be studied.

Questionnaire

Participants will be asked to fill out a printed questionnaire. The participants have also the option to fill in a web-based questionnaire, which will be accessible via a link provided in the information letter. After identification of control patients, a similar mailing will be sent to these controls.

Environmental and lifestyle factors like vaccination status, previous pregnancies in case of females, level of education and current professions (as a proxy for socioeconomic status) will be obtained via the patient information questionnaire. The questionnaire will add to the knowledge to these possible confounders in cases and controls.

In general, many questions will involve ‘life-time’ risk factors and information and are not particularly targeted at the time of implicated episode.

Racial confounder

Based on the knowledge that different ethnicities have varying frequencies of erythrocyte antigens, a so-called mismatch between a donor from one particular ethnicity and the recipient of another ethnicity does play a role in developing immune response to donor erythrocytes. Therefore, we will also attempt to document racial mismatch leading to RBC alloimmunisation. This is attempted by one question in the questionnaire but will foremost rely on the blood group typing, which usually determines the ethnicity.

Blood research and sampling

To investigate the effect of genetic factors on the risk of the development of alloantibodies, we will collect blood samples from all participants for extensively typing the blood to get an antigen profile and to look at genetic markers, which influence immune system and vaccination efficiency. SNP's in candidate genes (eg, coding for HLA types) modulating specific and innate immune responses will be assessed. Biomarkers typical for the activity of the immune response: cytokines and titres of antibodies against common (vaccinated) antigens can later be determined in the plasma and serum that are stored as well.

Statistical analysis

We expect to include a total of 500 case patients and 1000 controls.

Logistic regression models will be used to assess the association between the risk to develop antibodies and potential risk factors, adjusted for other risk factors and for the number of exposures to the antigen.

We will examine the association between the risk factor and alloimmunisation using logistic regression.

We will also make a selection of all cases and controls on the most frequently found antibodies and if the relative impact of risk factors and immune modulators on the risk of all the antibody types (in separate analysis) is in the same direction, we will make a generalised observation.

With 1500 patients, and the conventional 80% power and a p value of 0.05, we will be able to detect effects (OR) of dichotomised risk factors of 1.35 or higher.

An additional analysis will be performed along the lines of a ‘case-crossover’ design within the case patients. The ‘Hazard Period’ (time period right before the detection of a positive antibody) will be compared to a ‘Control Component’ (a specified time period other than the Hazard Period) in the case patient's medical history and the RR for the transient effect risk factors will be calculated.

Ethical considerations

Regulation statement

The study will have a multicentre design subjecting patients to a questionnaire and additional blood sampling. After approval by the central Medical Ethical Committee (MEC) of the Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC), the study clearly requires a local Medical Ethical Committee approval for each site that detects a probable transfusion-mediated alloimmunisation. Help of local investigators, usually the local haematologist or clinical chemist in charge of the transfusion laboratory, will be recruited to substantiate implementation of the study at the various sites. Each local investigator will in fact be responsible for ensuring that the study will be conducted in his centre in accordance with the protocol, the ethical principal of the Declaration of Helsinki, current International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) guidelines on Good Clinical Practice and applicable regulatory requirements.

Recruitment and consent

Data will be collected at each hospital site, Sanquin and from medical records and files. All data will be coded for privacy reasons. As said, after identification of cases and controls, patients will be sent a short and concise letter and an information brochure explaining the purpose of the study. This letter will be combined with the questionnaire and foremost—an answer card expressing willingness or refusal to participate in the study to fill in and return to the study's contact address. Participants, moreover, will have an option of filling in the questionnaire via the study's website. The web link access will be explained in the patient information. After receiving a patient's positive response to our request to participate, a follow-up call will be made by the investigator to answer any additional queries and if applicable to make an appointment for the blood taking. The patients would be invited to LUMC or the participating centres for blood taking. Additionally to the signed answer card for blood taking, patients would be informed about the study once again at the blood taking appointment, and a final consent form in presence of the study coordinator and data manager will be signed before the blood taking commences. Proper tubing and transfer material will be provided to the non-LUMC sites.

The patient burden

The reading of the information and completing the questionnaire (estimated to take about 10 min) will be of minimal patient burden or stress and is absolutely voluntary. Apart from the questionnaire, the protocol involves a single blood sampling of 25 ml as main discomfort for cases and controls. However, the blood taking will preferably be combined with a regular control and if possible a blood sampling.

The blood taking will be organised centrally at the LUMC upon invitations. There are no further interventions within the study protocol. The study has absolute minimum invasive risk for the patients.

Medical information, data and sample handling and reports

Per patient an electronic Case Record Form (CRF) with a unique study number (identifier) will be made. The CRFs will be subjected to independent data management. The principal investigators, Anske van der Bom and J J Zwaginga, will be responsible for the CRF and data management.

Patient-identifying parameters such as name, the hospital patient number and the full birth date will not be entered and found in the electronic CRF. The key between these identifying data and the unique study number will be only available to the data management at the Department of Epidemiology. These patient-identifying parameters are only needed for sending the questionnaire and making an appointment for blood taking, which will be done by the data management. The blood taking and further sampling will involve relabelling of the tubes to the specific study number.

There will be a provision to keep the patient personal details for the entire duration of storage of blood samples, with a possibility to track back and identify the patients with their blood samples. Coding measure will ensure that this information is not available to a third party and is only accessible via an encoding key to the principal investigators of the R-FACT study. Individual medical and investigational information obtained during the study is considered confidential and disclosure to third parties is prohibited. The described strategy will guarantee effective study of data together with maintaining optimal patient privacy.

The blood samples will be stored in state-of-the-art storage facilities at the LUMC, with storage management software for 20 years.

The research, patient information, blood sampling and storage will be conducted in accordance with LUMC's Good Research Practice guidelines.

Withdrawal of individuals

Subjects can decide to have their samples removed from the serum, plasma, DNA and RNA bank and thus from further research in the future at any time and for any reason, that is, meaning without consequences for their further clinical treatment.

Independent physician

Before consenting, patients can gather information or advice from the investigator and also from an independent physician. This name will be provided in the patient information.

Objection by minors or incapacitated subjects

Not applicable.

Group-related risk assessment and benefits

Not applicable.

Incentives

Not applicable.

Administrative aspects and publication

Handling and storage of data and documents

Data handling will comply with the Dutch Personal Data Protection Act.

A data manager (employed on the project) and the PhD fellow will extract data from the study sites and recode patients and locations to unique study codes under which non-patient identifying data are filed in a CRF per patient.

There will be no specific physical CRFs because of the massive patient/control numbers and electronic data sets can be often automatically extracted from the patient information systems present in most hospitals.

Amendments

All amendments will be notified to the MEC that gave a favourable opinion.

Annual progress report

The investigators will submit a progress summary of the study to Sanquin as sponsor of the study regularly. Information on inclusion of cases and controls, other problems and amendments will be provided as required by the regional and local MEC's.

End of the study report

The investigator will notify the accredited MECs of the end of the study within a period of 8 weeks. The end of the study is defined as the last data collected from medical records and case–control questionnaires.

Public disclosure and publication policy

The final publication of the study results will be written by the study coordinator(s) on the basis of the statistical analysis performed. A draft manuscript will be submitted to all co-authors for review. After revision, the manuscript will be sent to a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

Any publication, abstract or presentation based on patients included in the study must be approved by the study investigators and collaborators.

Expected results

Our case–cohort study will quantify and characterise risks of patients and conditions for transfusion-associated alloimmunisation, although a prospective serology study involving a first transfused cohort would be most preferable to add to the insight in primary immunisation (risk). However, 50% of first transfused patients never need new blood again and escape follow-up if not recalled. Moreover, the occurrence for the other 50% of the following transfusion period is quite variable. Therefore, a prospective study is viewed as cumbersome. On the more practical side for a case–control study, 50% of the transfused patients have been transfused before and these in principle are eligible as case or control patients. Indeed, in accordance by the rules for inclusion, these patients are already transfused at two different periods at least. Therefore, if we can define risk factors for alloimmunisation, then advanced matching of blood donors for this group should be regarded as valuable. Finally, strong synergy will be obtained between our study and the MATCH study by Schonewille et al. In the latter study, logistical/cost/and benefit aspects of advanced matching after formation of a first antibody will be determined.

Our study will contribute to classifying patients who could benefit from additional or extended typing and donor matching to prevent alloimmunisation. We envision to contribute to a matching policy based on a prognostic risk score for immunisation in general transfused patients.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Zalpuri S, Zwaginga JJ, van der Bom JG, et al. Risk Factors for Alloimmunisation after red blood Cell Transfusions (R-FACT): a case cohort study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001150. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001150

Collaborators: (1) Dr H Schonewille, Sanquin-LUMC Jon J van Rood Center for Clinical Transfusion research, Leiden, the Netherlands; (2) Professor JP Vandenbroucke, Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands; (3) Professor A Brand, Sanquin-LUMC Jon J van Rood Center for Clinical Transfusion research, Leiden, the Netherlands; (4) Professor E Briët Former Director, Sanquin Blood Bank, the Netherlands.

Contributors: All the above-mentioned authors fulfil the ICMJE guidelines criteria for authorship. All the authors have equally made: (1) substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and (3) final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This ongoing clinical study is funded by not-for-profit organisation—Sanquin Blood Supply, the Netherlands, grant number PPOC-08-006.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by the Medical Ethical Committee, Leiden University Medical Center.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Norol F, Nadjahi J, Bachir D, et al. [Transfusion and alloimmunization in sickle cell anemia patients]. Transfus Clin Biol 1994;1:27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schonewille H, Haak HL, van Zijl AM. Alloimmunization after blood transfusion in patients with hematologic and oncologic diseases. Transfusion 1999;39:763–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fluit CR, Kunst VA, Drenthe-Schonk AM. Incidence of red cell antibodies after multiple blood transfusion. Transfusion 1990;30:532–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zalpuri S, Zwaginga J, Cessie S, et al. Red-blood-cell alloimmunization and number of red-blood-cell transfusions. Vox Sang 2012;102:144–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asfour M, Narvios A, Lichtiger B. Transfusion of RhD-incompatible blood components in RhD-negative blood marrow transplant recipients. MedGenMed 2004;6:22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramsey G, Hahn LF, Cornell FW, et al. Low rate of Rhesus immunization from Rh-incompatible blood transfusions during liver and heart transplant surgery. Transplantation 1989;47:993–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shukla JS, Chaudhary RK. Red cell alloimmunization in multi-transfused chronic renal failure patients undergoing hemodialysis. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 1999;42:299–302 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reisner EG, Kostyu DD, Phillips G, et al. Alloantibody responses in multiply transfused sickle cell patients. Tissue Antigens 1987;30:161–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bacon N, Patten E, Vincent J. Primary immune response to blood group antigens in burned children. Immunohematology 1991;7:8–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauer MP, Wiersum-Osselton J, Schipperus M, et al. Clinical predictors of alloimmunization after red blood cell transfusion. Transfusion 2007;47:2066–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoeltge GA, Domen RE, Rybicki LA, et al. Multiple red cell transfusions and alloimmunization. Experience with 6996 antibodies detected in a total of 159,262 patients from 1985 to 1993. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1995;119:42–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seyfried H, Walewska I. Analysis of immune response to red blood cell antigens in multitransfused patients with different diseases. Mater Med Pol 1990;22:21–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hendrickson JE, Desmarets M, Deshpande SS, et al. Recipient inflammation affects the frequency and magnitude of immunization to transfused red blood cells. Transfusion 2006;46:1526–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reviron D, Dettori I, Ferrera V, et al. HLA-DRB1 alleles and Jk(a) immunization. Transfusion 2005;45:956–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiaroni J, Dettori I, Ferrera V, et al. HLA-DRB1 polymorphism is associated with Kell immunisation. Br J Haematol 2006;132:374–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noizat-Pirenne F, Tournamille C, Bierling P, et al. Relative immunogenicity of Fya and K antigens in a Caucasian population, based on HLA class II restriction analysis. Transfusion 2006;46:1328–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mason PM, Parham P. HLA class I region sequences, 1998. Tissue Antigens 1998;51:417–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dorman SE, Picard C, Lammas D, et al. Clinical features of dominant and recessive interferon gamma receptor 1 deficiencies. Lancet 2004;364:2113–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dhiman N, Ovsyannikova IG, Vierkant RA, et al. Associations between SNPs in toll-like receptors and related intracellular signaling molecules and immune responses to measles vaccine: preliminary results. Vaccine 2008;26:1731–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhiman N, Ovsyannikova IG, Cunningham JM, et al. Associations between measles vaccine immunity and single-nucleotide polymorphisms in cytokine and cytokine receptor genes. J Infect Dis 2007;195:21–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larcombe L, Rempel JD, Dembinski I, et al. Differential cytokine genotype frequencies among Canadian Aboriginal and Caucasian populations. Genes Immun 2005;6:140–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDade TW, Rutherford JN, Adair L, et al. Population differences in associations between C-reactive protein concentration and adiposity: comparison of young adults in the Philippines and the United States. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89:1237–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.