Abstract

Background

The Affordable Care Act mandates that new insurance plans cover smoking-cessation therapy without cost-sharing. Previous cost difference estimates, which show a spike around the time of cessation, suggest premiums might rise as a result of covering these services.

Purpose

The goal of the study was to test (1) whether individuals in an RCT of pharmacotherapy and counseling for smoking cessation differed in their healthcare costs around the cessation period, and (2) whether the healthcare costs of those in the trial who successfully quit were different from a matched sample of smokers in the community.

Methods

Generalized linear regression models were used to analyze healthcare cost data on individuals enrolled in a comparative effectiveness trial of cessation therapies between October 2005 and May 2007. Cost differences for the period preceding and subsequent to the cessation attempt were assessed by trial participants' 12-month sustained quit status. Healthcare cost differences between sustained quitters and a sample of community-dwelling smokers, matched to these quitters on the basis of health services use around the time trial participant enrolled and by demographics, were also examined. Data were analyzed in 2011.

Results

All three groups had a spike in cost associated with the index clinic visit. Regression results revealed little difference in healthcare costs by quit status for trial participants until the sixth quarter post-quit. By that quarter, continuous sustained quitters cost $541 (p<0.001) less than continuing smokers. Continuous sustained quitters cost less than their matched community-dwelling smokers in almost every quarter observed. The cost difference ranged from $270 (p=0.01) during the quarter of quit, to $490 (p<0.01) in the 6th quarter after quitting.

Conclusions

The inclusion of smoking-cessation therapy does not appear to raise short-term healthcare costs. By the sixth quarter post-quit, sustained quitters were less costly than trial participants who continued smoking.

Trial registration

This study is registered at clinicaltrials.gov NCT00296647.

Background

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 mandates coverage of certain preventive health services, including smoking-cessation treatment, without any patient cost-sharing in new health insurance plans. 1Prior to this, only six states mandated smoking-cessation coverage among private insurance plans,2 and many state government employee health insurance plans did not include coverage for smoking cessation.3 Cost-sharing has previously been shown to reduce the use of these therapies, so coverage of these services coupled with the individual insurance mandate will likely provide increased access to treatment for many smokers.4

It is not clear what impact this increased use will have on healthcare costs. New plans will no longer be able to leave out this coverage to separate smokers from nonsmokers through benefit design. Thus, mandated coverage of cessation could increase premiums for all individuals if cessation therapy simply adds to the cost of care. On the other hand, if cessation reduces healthcare costs, then premiums could be lower as a result.

Previous studies of a variety of patient populations have found similar results: smokers who quit show a spike in healthcare use and costs that begins just prior to cessation and escalates after cessation.5–7 This suggests that successful cessation often occurs in the midst of an expensive healthcare episode, with healthcare use among former smokers returning to the level experienced by continuing smokers within 1 year following cessation.6

Most studies addressing the topic of cessation-related costs were conducted within integrated healthcare systems that provide health services to a defined population. The unique aspects of healthcare delivery and finance in these systems may affect health care use in ways that are not generally representative. Under the ACA mandate of cessation therapy coverage without cost-sharing, all insured patients who smoke should be counseled to undertake cessation therapy irrespective of insurer type. The propensity to use other health services by those who would now be using cessation therapy and the cost impacts may be substantially different than those found in previous studies, which were conducted in a closed-panel setting. Thus, existing estimates of cost differences around the time of cessation need to be examined outside the closed-panel integrated care setting.

This paper quantifies healthcare cost differences between smokers who quit and those who continued to smoke in the 18 months following a quit attempt. The first innovation is that the data are from individuals covered by a variety of health insurance plans who enrolled in cessation therapy. The estimates of healthcare costs around cessation are derived from individuals enrolled in a comparative effectiveness trial of free (to the patient) smoking-cessation treatments that are consistent with Public Health Service (PHS) Clinical Practice Guideline recommendations.8

Another innovation is the analysis of a demographically matched sample of smokers who were not approached for the trial but who were receiving primary care at the same clinics, for the same diagnoses, and making clinic visits at around the same time, as patients enrolled in the trial. This provides insight into whether those willing to enroll in the trial are different from the population of smokers in terms of healthcare costs and the counterfactual of what healthcare costs smokers might have incurred had they not quit smoking.

Methods

Research Setting and Subjects

This research was conducted in conjunction with an RCT of evidence-based smoking-cessation treatments administered to 1346 individuals making primary care visits to one of 12 Aurora primary care clinics in Milwaukee WI from October 2005 through May 2007.8 Aurora Health care is a not-for-profit healthcare delivery system that serves 90 communities in eastern Wisconsin and is available to Wisconsin residents through over 44 different insurance providers. For clarity throughout the remainder of the paper, individuals who were approached and enrolled in the comparative effectiveness trial are referred to as “participants”. The study received full IRB review and approval from Aurora Health Care and the University of Wisconsin.

Details on the specific cessation services and outcomes from the parent study are provided elsewhere.8 The RCT assessed the willingness of smokers making routine primary care visits to accept no-cost smoking-cessation services and the subsequent abstinence rates among those willing to attempt cessation. This RCT evaluated the effectiveness of three FDA-approved monotherapies (Nicotine Patch, Bupropion SR, and Nicotine Lozenge) and two combination therapies (Bupropion + Lozenge, Patch + Lozenge), with all pharmacotherapies accompanied by proactive phone counseling provided through a tobacco quitline. There was no medication placebo condition.

During the recruitment period, clinic staff assessed the smoking status of all adults making primary care visits to one of the 12 selected clinics. Adults (aged ≥18 years) currently smoking ≥10 cigarettes per day for the past 6 months and motivated to quit were identified for potential inclusion in the study. Each randomly chosen current smoker interested in cessation who met the study's inclusion criteria and whose physician provided medical clearance to join the study was contacted by a member of the research team who explained the study, invited the individual to enroll, and obtained verbal informed consent.

Matched Sample

Twelve months into the study, trial participants were matched on an approximately 3:1 ratio (three matches for each participant) to smokers being treated at the same clinics. To be included, matched sample individuals had to meet five criteria. These individuals: (1) had to have a visit to the same clinic as the participant within the same time frame as the participant they were matched to (±2 weeks); (2) be a current smoker at the time of that outpatient visit and continue to smoke according to their medical record, (3) could not have been approached for enrollment in the trial (individuals were approached based on randomization), (4) had to be of the same age and gender as the participant and (5) had to have the same clinical reasons for their clinic visit as those of the participant to which they were being matched (determined by Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for the visit). For clarity these individuals will be referred to as “matches” hereafter.

Survey Data

Individuals who consented to participate provided information not available from health plan records including marital and employment status, race, education and smoking history including the age at first cigarette, the mean daily number of cigarettes smoked and history of quit attempts. Individuals were asked to set a date for their quit attempt and were provided instructions to pick up study medications at the clinic pharmacy. Only individuals who picked up their prescription from the pharmacy were considered enrolled in the trial.8

Data Collected from Health Plan Information Systems

Information on all services provided by Aurora Health Care was obtained for 18 months preceding the initial trial recruitment and for 18 months following the date at which the last trial participant joined the study. Data were obtained from the Center for Urban Population Health (CUPH), who partners in conducting health systems research with Aurora Health Care, the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, and the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee's College of Health Sciences. The CUPH maintains comprehensive data on public health and healthcare use provided in part by Aurora Health Care and served as the coordinating center for the primary and secondary data used for this research.

The following health services information was collected for participants and matches: All inpatient services at Aurora hospitals including ICD-9-CM diagnoses, ICD-9-CM procedures and Diagnosis Related Groups (DRGs); all outpatient services including ICD-9-CM diagnoses and CPT codes. The wholesale pharmaceutic cost of the duration of cessation therapy8 was included in the outpatient cost for the month the individual enrolled in the trial. Unfortunately, due to challenges in assigning costs to other pharmacy use data, the analyses in this paper are restricted to inpatient and outpatient services and these cessation-therapy costs.

Data were in the form of claims submitted to insurers for services provided to study participants (including matches). These data were then organized by category of service (outpatient and inpatient) and each record was examined to re-create a unique healthcare encounter. Costs were assigned to these services on the basis of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) fee schedules for each service. DRG payments were assigned for inpatient services and the Resource Based Relative Value Scale was used for outpatient services. The resource intensity weight and reimbursed amount was applied for the specific year the service was provided. Services not assigned a cost by CMS were assigned costs using CPT-based “gap codes” with costs for these health services provided by the Ingenix Corporation, which was required in less than 5% of the services. Healthcare costs were adjusted for inflation using the Milwaukee component of the Medical Consumer Price Index, and all dollar values are reported adjusted to 2009.

Analytic Methods

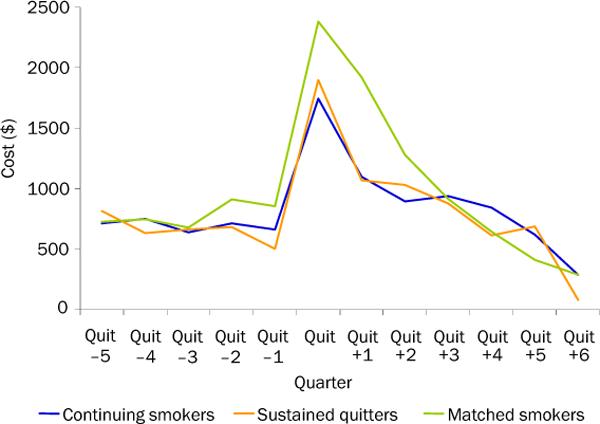

Graphical analysis of trends in unadjusted healthcare costs per quarter over the period of observation is provided to facilitate comparisons to previous studies that demonstrate a spike in healthcare cost around the time of cessation.6,7 The index quarter is defined as the quarter ending with the month the individual was enrolled in the trial. This analysis shows the trend in the sum of inpatient and outpatient costs for participants, according to whether they were sustained quitters (defined as self-reported continuous abstinence at 12 months) or the matches for the sustained quitters.

Regression methods were used to estimate the differences in healthcare costs between participants who were sustained quitters and participants who were not, and between participants who were sustained quitters and their matches. Initially, separate models were estimated in which healthcare costs in the entire period from the index month through the 18 months following were compared between: (1) participants who had sustained quitting and those who did not, and (2) participants who had sustained quitting and their matches. These were then analyzed by inpatient and outpatient costs separately.

Because aggregated costs in the post-enrollment period are unable to reveal subtle changes in cost trends between different groups, a second set of estimations was conducted. To capture these potential changes in the trend in healthcare costs of participants who were sustained quitters compared to those who continued to smoke, differences in costs were analyzed quarterly. These differences were estimated relative to the costs in the quarter that occurred five quarters prior to the quarter of the quit attempt.

These estimates were examined for each of the quarters leading up to and including the quit quarter as well as for the six quarters following the quit quarter. These models were then estimated separately for inpatient and outpatient costs. The second analysis was identical to the above, except it compared quarterly healthcare costs of participants who were sustained quitters relative to their matches. As in the previous analysis, separate equations were also estimated for inpatient and outpatient costs.

Models using the trial participants were adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, years smoked prior to quit, smoking heaviness (an average of ≥1 pack of cigarettes per day vs less), marital status and education. Models comparing participants who quit to their matches were adjusted for gender and age, the only demographic characteristics available for the matches. Because healthcare costs are typically highly skewed, linear regression models may yield biased SEs for regression coefficients, yielding invalid statistical inference and thus requiring modeling techniques that have been described elsewhere.9–12 Models were estimated in 2011 using STATA 12 using generalized linear models, specifying a gamma distribution and a log-link function and calculating robust SEs for regression coefficients.12 This approach has been used in previous research examining time-series data on the healthcare costs of smoking,6 and in a variety of other healthcare cost analyses.14,15

Results

Requisite data were available for 1338 of the 1346 trial participants. Of these, 22.6% (n=302) were sustained quitters at 12 months. Figure 1 shows the comparison of total inpatient and outpatient costs by quarter. Costs reach a peak in the quarter of quit. The mean cost in the index quarter for participants who did not sustain quitting was $1745 (95% CI=$1179, $1519). Among those who sustained quitting, these costs were $1898 (95% CI=$1475, $2321) and among matches to these participants the cost in this quarter was $2419 (95% CI=$2522, $3155).

Figure 1.

Total inpatient and outpatient costs by subsample

The healthcare cost comparisons of participants who sustained quitting with those who did not, aggregated for the period following the quit attempt, are in Table 1. Participants did not differ in these aggregate costs by smoking status. Separating costs by care setting did not change this. Table 2 displays the comparison between participants who sustained quitting and their matches. In this comparison, total post-quit costs were again not different. However, inpatient costs were lower among the participants (−$1292, p=0.009) while outpatient costs were higher ($335, p=0.001).

Table 1.

Total post-quit cost difference for participants who were sustained quitters at 12 months compared to participants who were not

| N=1338 | Total costs | p-value | Inpatient costs | p-value | Outpatient costs | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants who sustained quitting | −453 | (0.344) | −490 | (0.258) | 2 | (0.986) |

Robust p-values in parentheses, bold indicates p-value <0.05.

Model adjusted for individual age, gender, race/ethnicity, years smoked prior to quit, whether they smoked a pack or more a day, marital status, and education.

Table 2.

Total post-quit cost difference for participants who were sustained quitters at 12 months compared to their matches

| N=1203 | Total costs | p-value | Inpatient Costs | p-value | Outpatient Costs | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants who sustained quitting | −932 | (0.09) | −1292 | (0.009) | 335 | (0.001) |

Note: Robust p-values in parentheses, bold indicates p-value <0.05. Model adjusted for individual age and gender

The trends in cost differences relative to the costs five quarters prior to quitting reveals something slightly different (Table 3). In comparison to participants who did not sustain quitting, participants who sustained quitting had lower overall costs in the sixth quarter post-quit (−$541, p<0.001). This effect was driven by lower inpatient costs (−$445, p<0.001). Those participants who sustained quitting also had lower inpatient costs in the fourth quarter post-quit (−$241, p=0.031), although this did not lead to lower total costs.

Table 3.

Incremental healthcare cost comparisons for trial participants who did versus did not sustain 12-month smoking abstinencea

| Quarter | Total costs | p-value | Inpatient Costs | p-value | Outpatient Costs | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior to quit | ||||||

| 4 | −242 | (0.025) | −207 | (0.021) | −17 | (0.477) |

| 3 | −69 | (0.677) | −57 | (0.696) | 0 | (0.997) |

| 2 | −127 | (0.399) | −149 | (0.219) | 49 | (0.234) |

| 1 | −289 | (0.008) | −270 | (0.002) | 8 | (0.809) |

| Quit | −78 | (0.560) | −121 | (0.300) | 71 | (0.063) |

| Post-quit | ||||||

| 1 | −142 | (0.331) | −165 | (0.137) | 57 | (0.154) |

| 2 | 12 | (0.944) | −46 | (0.739) | 86 | (0.085) |

| 3 | −139 | (0.435) | −187 | (0.136) | 119 | (0.064) |

| 4 | −242 | (0.120) | −241 | (0.031) | 51 | (0.338) |

| 5 | −94 | (0.666) | −145 | (0.328) | 93 | (0.345) |

| 6 | −541 | (0.000) | −445 | (0.000) | −44 | (0.297) |

Note: Robust p-values in parentheses, bold indicates p-value <0.05. Model adjusted for individual age, gender, race/ethnicity, years smoked prior to quit, whether they smoked a pack or more a day, marital status, and education.

Relative to costs five quarters prior to quitting attempt

In comparison to their matches, the participants who sustained quitting had lower costs across much of the period (Table 4). There was no difference in the third through fifth quarter post-quit, but by the sixth quarter, there was a large difference (−$490, p=0.009). This difference was again driven by lower inpatient costs in that period (−$461, p=0.001).

Table 4.

Incremental healthcare cost comparisons of trial participants with 12-month smoking abstinence versus matched smokers not in the triala

| Quarter (months pre/post - quit) | Total costs | p-value | Inpatient Costs | p-value | Outpatient Costs | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior to quit | ||||||

| 4 | −315 | (0.011) | −275 | (0.011) | −38 | (0.088) |

| 3 | −295 | (0.034) | −227 | (0.079) | −66 | (0.000) |

| 2 | −345 | (0.006) | −288 | (0.009) | −55 | (0.032) |

| 1 | −554 | (0.000) | −457 | (0.000) | −99 | (0.000) |

| Quit | −270 | (0.047) | −323 | (0.001) | 21 | (0.546) |

| Post-quit | ||||||

| 1 | −371 | (0.003) | −297 | (0.008) | −74 | (0.000) |

| 2 | −317 | (0.017) | −278 | (0.013) | −25 | (0.435) |

| 3 | −221 | (0.256) | −219 | (0.164) | 28 | (0.580) |

| 4 | −8 | (0.979) | −45 | (0.857) | 50 | (0.405) |

| 5 | 408 | (0.391) | 299 | (0.450) | 107 | (0.314) |

| 6 | −490 | (0.009) | −461 | (0.001) | −12 | (0.832) |

Note: Robust p-values in parentheses, bold indicates p-value <0.05. Model adjusted for individual age and gender.

Relative to costs five quarters prior to quitting attempt

Discussion

The current results confirm previous findings of a `spike' in healthcare costs around the time of cessation among quitters enrolled in a cessation trial. However, in this sample the spike is also evident among continuing smokers from the trial. Thus, when comparing participants who were quitters to those who were continuing smokers the quitters do not cost more at the time of and in the period following quit, and by six quarters post-quit, cost less than continuing smokers.

The matched sample is substantially more expensive in the period prior to the clinic visit matched to the visit in which the quitters were enrolled. Perhaps those who were willing to accept cessation treatment were actually healthier than the general population of smokers making healthcare visits during the same time period, which is in contrast to previous findings. Moreover, relative to the matched sample, participants who were sustained quitters still had lower costs at most points over the study period. This difference is most apparent by 18 months after quitting and appears to be driven by inpatient cost differences. It is important to note that in the current study, the spike in costs seen in both participants and matches is due to the fact that the recruitment strategy for the trial was to approach individuals making primary care clinic visits. The level of costs in the period surrounding the outpatient visit suggests that this spike is due to more than just a routine outpatient visit for some of these patients.

Taking the results in Tables 3 and 4 together, it appears these costs are due to medical status at the time of the clinic visit and not cessation. In addition, the reduced cost in the sixth quarter is suggestive of faster declines among those who successfully quit. However, there are no data from after this point to establish whether this trajectory persists.

The current study has limitations. First, the study was powered to examine clinical effectiveness not economic outcomes, so caution needs to be taken in interpreting lack of significance as definitive.16 Second, pharmacy costs other than the cessation therapies could not be assigned, and these are not included in the models. Given that differences were largely attributable to inpatient costs, this is a concern to the degree that pharmacy substitutes for hospitalization.

Third, data on health services use outside of Aurora Health care were unavailable. If the propensity to use outside care was somehow correlated with quit status, then this could confound the estimates. Fourth, human subjects protections precluded analysis of the healthcare costs of individuals who declined enrollment in the trial. Thus, cost differences are potentially biased to the degree that these individuals' costs might systematically differ from those who refused enrollment in the trial. It is argued here that the matched-sample analysis addresses this concern to some degree. Finally, the results are from a single healthcare system in a single urban area, which necessarily limits generalizability.

Conclusion

Under the ACA mandate of full coverage for smoking-cessation services, more primary care settings may provide cessation treatment to smokers as the barrier of out-of-pocket costs will have been removed for those who are insured. This study provides evidence that those who accept cessation treatment in the outpatient setting incur lower healthcare costs by 18 months following quitting. Addressing smoking cessation in primary care raises little concern for additional costly healthcare use in the short term and holds promise to reduce healthcare costs within a relatively brief period of time.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by P50 DA019706-100002 Natural History of Smoking & Quitting: Longterm Outcomes.

JMH is an investigator at the Comprehensive Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation (CADRE) Center, funded by U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development Service (VA HSR&D). The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the official position of VA HSR&D. Over the last 5 years, MCF has served as an investigator on research studies at the University of Wisconsin that were funded wholly or in part by Nabi Biopharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer. From 1997 to 2010, MCF held a University of Wisconsin (UW) named Chair for the Study of Tobacco Dependence, made possible by a gift to UW from GlaxoWellcome. No other financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cassidy A. Health Affairs. Health policy brief: Preventive services without cost sharing. www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=37. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Lung Association . State laws mandating coverage of cessation treatments. www.lungusa.org/assets/documents/CESSATION_DB_PDF_10.PDF. [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Lung Association . State Tobacco Cessation Coverage Database. www.lungusa.org/cessationcoverage. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curry SJ, Grothaus LC, McAfee T, Pabiniak C. Use and cost effectiveness of smoking-cessation services under four insurance plans in a health maintenance organization. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(10):673–679. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809033391006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner EH, Curry SJ, Grothaus L, Saunders KW, McBride CM. The impact of smoking and quitting on health care use. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1789–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fishman P, Khan Z, Thompson E, Curry S. Health care costs among smokers, former smokers and never smokers in an HMO. Health Services Res. 2003;38(2):721–37. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fishman P, Thompson EE, Merikle E, Curry SJ. Changes in health care costs before and after smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(3):393–401. doi: 10.1080/14622200600670314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith SS, McCarthy DE, Japuntich SJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness of five smoking cessation pharmacotherapies in primary care clinics. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(22):2148–55. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duan N, Manning WG, Morris CN, Newhouse JP. A comparison of alternative models for the demand for medical care. J Bus and Econ Statistics. 1983;1:115–26. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manning WG. The logged dependent variable, heteroscedasticity, and the retransformation problem. J Health Econ. 1998;17(3):283–95. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(98)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mullahy J. Much ado about two: reconsidering retransformation and the two-part model in health econometrics. J Health Econ. 1998;17:247–81. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(98)00030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manning WG, Mullahy J. Estimating log models: to transform or not to transform. J Health Econ. 2001;20:461–94. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huber PJ. Robust statistics. Wiley; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilmer TP, O'Connor PJ, Manning WG, Rush WA. The cost to health plans of poor glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1847–53. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.12.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barber JA, Thompson SG. Multiple regression of cost data: use of generalized linear models. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2004;9(4):197–204. doi: 10.1258/1355819042250249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glick HA, Doshi JA, Sonnad SS, Polsky D. Economic evaluation in clinical trials. Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]