Abstract

High levels of depressive symptoms are common and contribute to poorer clinical outcomes even in geriatric patients who are already taking antidepressant medication. The Depression CARE for PATients at Home (Depression CAREPATH) intervention was designed to meet the needs of medical and surgical patients who suffer from depression. The intervention’s clinical protocols are designed to guide clinicians in managing depression as part of routine home care.

INTRODUCTION

Most clinicians have observed depressive symptoms in many of their older medical/surgical patients (Brown, McAvay, Raue, Moses, & Bruce, 2003; Bruce et al., 2002; Ell, Unutzer, Aranda, Sanchez, & Lee, 2005; Suter, Suter, & Johnston, 2008). High levels of depressive symptoms that persist across time are clinically significant whether or not a patient has received a formal depression diagnosis or is already taking antidepressant medication. Given the negative impact of depression on clinical care and outcomes in medical and surgical patients, these depressed patients require ongoing depression care management (Suter et al., 2008).

The Depression CARE for PATients at Home (Depression CAREPATH) intervention was designed specifically for use in home healthcare in managing depression as part of ongoing care for medical and surgical patients. The CAREPATH intervention was designed to be delivered by nurses, physical therapists and primary providers in the home. Training occupational therapists and other care providers to assist in the delivery further strengthens the intervention. A key feature of the intervention is that rather than assigning depression care management (DCM) to a specialist, all primary clinicians are expected to manage depression as part of the routine care provided to their patients. The DCM protocol guides clinicians in when and how to take advantage of specialists and other resources. Home care clinicians are expected to manage an array of patients problems in addition to the presenting, mostly acute, conditions and to consult experts as needed. Thus the management of depression is treated like the management of many other medical conditions.

The purpose of this article is to describe the clinical protocols developed as part of the Depression CAREPATH intervention to guide home care clinicians in the management of depression in their medical and surgical patients. The intervention also helps home health agencies (HHA) develop the infrastructure needed to implement and sustain depression care management (DCM) as part of routine care. Effective use of the DCM protocol by clinicians requires that each HHA tailor key procedures to fit its own resources and routines. For example, HHAs should specify their own guidelines for case coordination so that clinicians will know whom to contact (e.g., the patient’s physician, a psychiatric nurse, another specialist) when case coordination or referral is indicated by the DCM protocol. Similarly, each HHA should tailor a suicide risk protocol that operationalizes both gradations of suicide risks and the specific steps that should be taken by clinicians at each stage. They should also develop a list the mental health resources available in the communities that serve their patients.

TWO PROTOCOLS

The Depression CAREPATH includes a “Screening Protocol” for identifying patients who require depression care management (DCM) as well as the “DCM Protocol” itself. Each is described, below.

Depression Screening Protocol

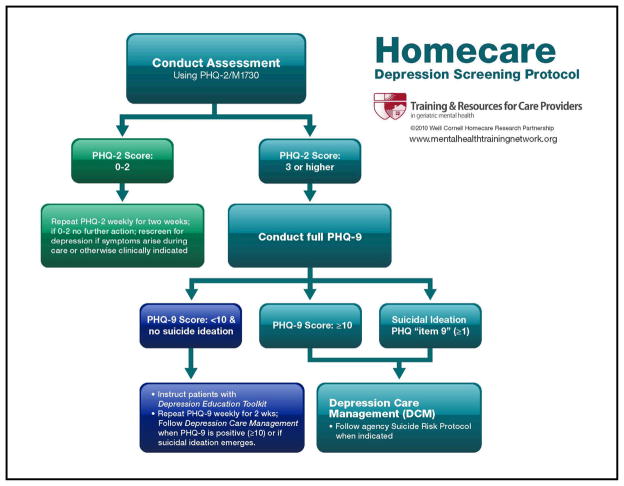

The recommended process for identifying patients who require depression care management is illustrated in Figure 1. The Depression Screening Protocol builds on the start-of-care OASIS M1730. It is recommended that agencies use the PHQ-2 option to screen for depression because it: (1) assesses the two “gateway symptoms” of depression, including little interest or pleasure in doing things and experiencing a depressed mood, at least one of which is required in determining a clinically significant depression; (2) is an evidence-based approach to depression screening (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2003), and (3) leads naturally to the PHQ-9, a well-used measure of depression severity that is also a component of the DCM protocol (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001).

Figure 1.

Depression Screening Protocol

Patient who screen positive for depressive symptoms on the PHQ-2 should then be assessed with the full PHQ-9 to determine depression severity. Consistent with the CMS OASIS-C Guidance Manual (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2009), research (Lowe, Kroenke, & Grafe, 2005) and clinical experts (Carson & Vanderhorst, 2010), a total score of 3 or higher is the recommended indicator for additional assessment. Because the first two questions of the PHQ-9 have been asked by the PHQ-2, the most efficient approach is to ask the PHQ-9’s remaining seven questions immediately following M1730. Agencies may, however, decide to use a lower cut-off score on the PHQ-2 as criterion for further assessment or to have nurses conduct a full PHQ-9 later in the visit. More thorough discussion of how to use the PHQ-9 in home healthcare has been discussed elsewhere (Ell et al., 2005; Sheeran et al., 2010).

Who Requires Depression Care Management

Home health patients require DCM when they experience clinically significant depressive symptoms, regardless of whether or not they are currently taking antidepressant medication or have a formal depression diagnosis. The screening protocol identifies clinically significant depression as a score of: a. 10 or higher on the total PHQ-9, or b. 1 or higher on the PHQ-9’s Item 9 (“Thoughts of death or harming yourself”). Because Item 9 screens for suicide ideation, a clinician should always follow positive responses to Item 9 with additional questions to determine the level of such risk and follow their agency’s own suicide risk protocol as indicated.

Patients who screen positive for depressive symptoms on the PHQ-2 but score less than 10 on the PHQ-9 may have mild levels of depression. These patients may be evaluated by their physician if judged to be clinically indicated, but, as standard practice, we recommend that such patients be monitored with weekly PHQ-9 scores for two weeks to identify patients whose depression is worsening or those who may have under-reported symptoms at the start of care. Such information on the course of depressive severity is useful for reevaluating the need for DCM. While monitoring symptoms, it is also recommended that clinicians provide these patients and their families educational materials about depression and depression treatment.

The protocol recommends weekly PHQ-2 screening for two weeks for patients who score 2 or less at the start of care. Clinicians have frequently commented that some patients may be more willing to acknowledge depressive symptoms after they have gotten to know the clinician better or when the immediate medical needs that led to home health care are under control.

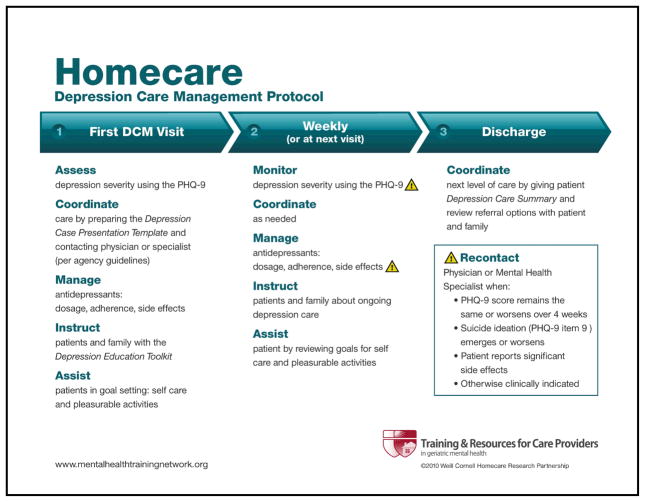

Homecare Depression Care Management Protocol

The Homecare DCM protocol (Figure 2) is designed to fit within a routine visit. The protocol should be followed weekly or, for patients seen less frequently, at each visit. For patients whose depression is identified at first visit, the initial DCM visit may be integrated into this visit or as part of a more extended start of care. Each DCM visits involves five basic (and interrelated) clinical functions: 1. Assessment, beginning with the full PHQ-9; 2. Case coordination; 3. Medication management; 4. Education of patients and families; and 5. Patient goal setting. Each is described below.

Figure 2.

Depression Care Management Protocol

a. Assessment

The purpose of depression assessment is not to make a formal diagnosis but to identify its presence and follow the course of clinically meaningful symptoms across time. The DCM protocol recommends using the PHQ-9 as an efficient, evidence-based approach to quantifying depression severity and changes in severity over time. Because it was originally developed for use in primary care, many physicians understand the clinical meaning of PHQ-9 scores, thus making communication with physicians easier. The symptoms assessed by the PHQ-9 parallel those of DSM-IV criteria for major depressive episode, so that physicians and specialists may use the results in diagnostic decision making as well as determining severity.

The DCM protocol requires that clinicians assess depressed patients with the full PHQ-9, and document these scores on a weekly basis and at discharge from the HHA. The ongoing record or chart of weekly scores is useful in clinical decision making, case coordination, discussions with physicians, and patient education.

b. Case Coordination

Case coordination is integral to DCM, and an expected first step following the first DCM visit. Evidence of clinically significant depressive symptoms indicates that some form of treatment may be needed or, for patients already taking an antidepressant, a review and possible change in treatment is required. The steps for case coordination will depend upon the agency and its resources, and should be developed into formal guidelines for clinicians. Typically, these guidelines require clinicians to contact the patient’s physician, although agencies with psychiatric nurses, clinically trained social workers, or access to other mental health specialists may designate these clinicians as the initial point of contact. It is important, however, that case coordination at some point involve someone with the professional knowledge and authority to make changes in medications, especially for symptomatic patients who are already taking an antidepressant or patients with very high PHQ-9 scores.

The DCM protocol requires that clinicians re-contact the patient’s physician or mental health specialist when depressive symptoms or suicide ideation emerge or worsen, patients have adverse side effects to medications, if there has been no change in symptoms after 4 weeks or otherwise clinically indicated. As discussed above, providing a record or chart of the weekly PHQ-9 scores will be important to clinical decision making in these consultations.

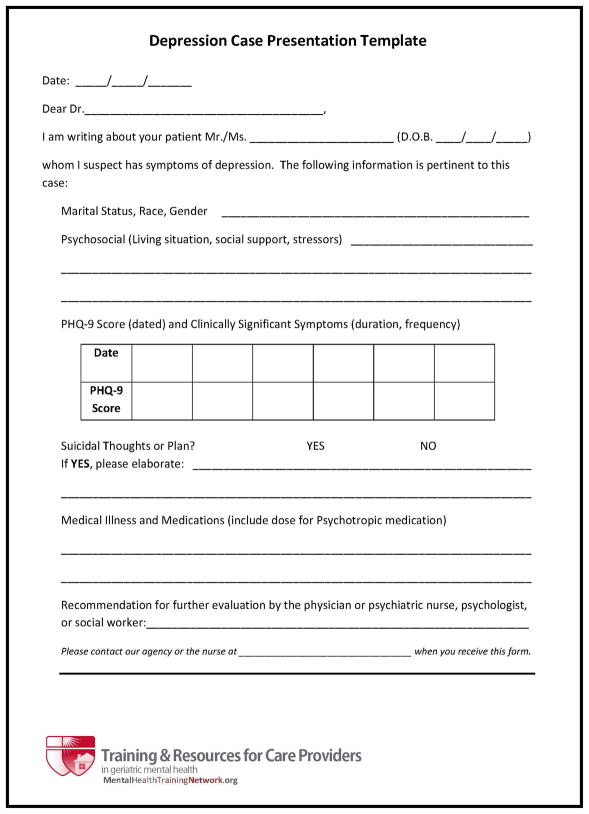

Case coordination is most effective when clinicians present information to physicians that is clear, concise, and contains the information needed by physicians for their own decision making. A Case Presentation Template, shown in Figure 3, was developed to facilitate such as a discussion (Brown et al., 2010). Clinicians who are unable to reach the physician can fax or email the pertinent information using this same tool. This information includes clear and unembellished statements regarding the: 1. Reason for the call; 2. Patient’s age, gender, race/ethnicity, and marital status; 3. The symptoms of depression, their duration and severity (PHQ-9 score), suicidal ideation, psychiatric history (if any); 4. Key psychosocial factors (e.g., living situation or social support stressors); 5. Medical illnesses, medications, and 6. Recommendation for further evaluation by MD or psychiatric nurse. It was found that, with training, case presentations following this template usually take less than two minutes.

Figure 3.

Depression Case Presentation Template for Use By Nurses

At discharge, it is important that information on depression and depression care is available to the patient’s primary care physicians or other clinicians who will be providing patient care. As it is not always possible for this information to be transferred directly from an agency, it is recommended that clinicians provide patient and their families a summary of their depression care with the instructions to bring it with them to their next doctor’s visit and next level of care. The Case Presentation Template (Figure 3) can be modified for this purpose. The summary is important to a successful transition of care for patients with short, as well as long, lengths of stay.

c. Medication Management

Antidepressant medication and psychotherapy are the most effective treatments for depression in late life. The most commonly used treatment is antidepressant medication, most often a Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) or a Serotonin–Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor (SNRI) although other classes of antidepressants are also effective. Approximately one in three geriatric home healthcare patients will be already taking an antidepressant at the start of care (Shao, Peng, Bruce, & Bao, in press) and a significant number of patients taking an antidepressant will still be experiencing clinically significant depressive symptoms (Bruce et al., 2007). The persistence of symptoms despite antidepressant medication is an indicator that a review of, and possible change in, treatment is indicated.

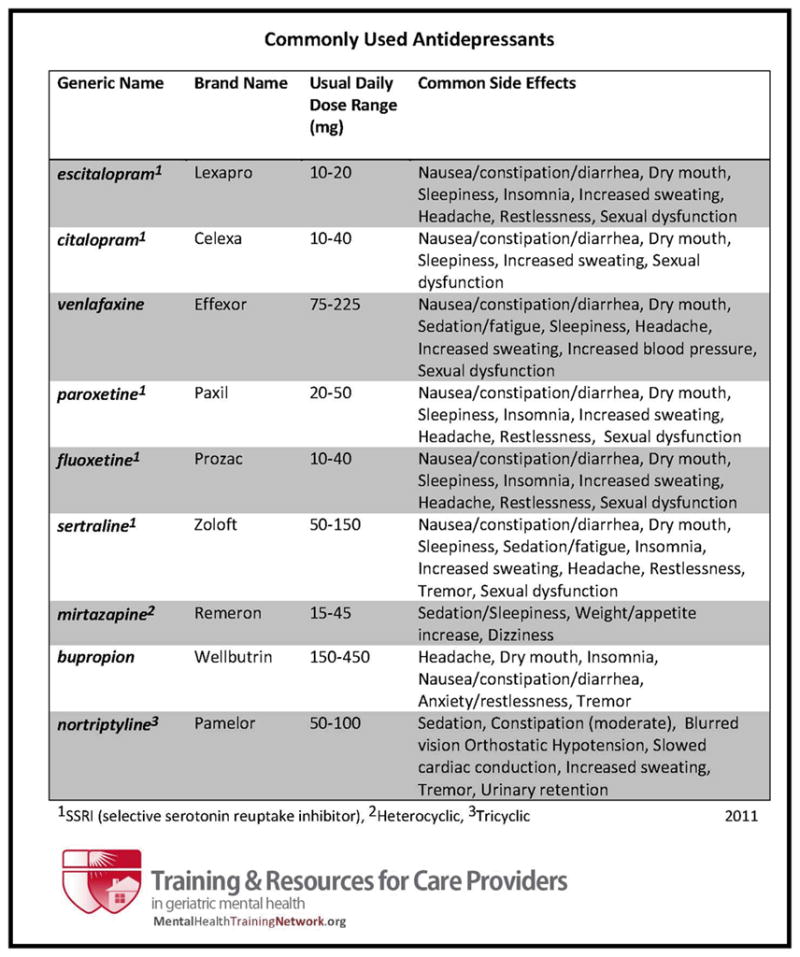

While managing antidepressant medication is similar to general medication management, there are several additional considerations. First, patients already taking an antidepressant may have been prescribed a subtherapeutic dose. In the general population, older patients taking antidepressants are over 2.5 times more likely to have received their prescription from an general medical provider than a psychiatrist, increasing the likelihood that they will not receive even the minimum recommended therapeutic dose of their specific antidepressant (Mojtabai & Olfson, 2008). More generally, finding an effective antidepressant regimen for a specific patient can take time. The therapeutic dose for most antidepressants is not a single value but falls within a range of values. Treating depression often involves changing doses, changing to a different antidepressant (or different class of antidepressant) or augmenting one medication with another. Therefore, basic knowledge of antidepressant classes and access to information on dosing for specific antidepressants is useful to clinicians in discussions with physicians. A list of commonly used antidepressants (Figure 4) can be useful to clinicians while conducting home visits, although they will want additional information for more complex circumstances.

Figure 4.

Commonly Used Antidepressants

As with other medications, managing antidepressants involves understanding possible side-effects. An advantage of SSRIs and SNRIs is that serious side effects are rare, although knowledge about how to identify them and when to contact a physician is important. Most side effects are not serious, however, and appear within days after the patient first begins taking the medication or after an increase in dosage. Most are also transient and normally resolve within a few weeks. Clinicians can help patients with interventions to help them cope with side effects until they resolve. Sometimes patients misinterpret symptoms of depression (such as fatigue or lack of appetite) as side effects of medication. It is useful to determine whether the symptoms preceded the antidepressant, and if so, reassure patients that the depression, not the antidepressant, is causing the problem.

Like other medications, adherence to antidepressants increases the likelihood of their being effective. A challenge in promoting adherence to antidepressants, however, is that most patients do not respond to antidepressant medication for several weeks. Full remission may take much longer. Patients who do not get better quickly may want to stop their medication because they feel discouraged. Similarly, it is usually recommended that antidepressant treatment last a year or more after the acute phase (i.e., after symptoms resolve). Patients who begin to feel better may want to stop taking their medication. Clinicians can intervene by reminding patients that they should never make changes to antidepressant treatment without supervision by their physician or other treating clinician. As discussed below, helping patients understand the purpose of antidepressant medication and dispel myths about depression can also promote adherence (Feldman et al., 2009).

d. Education

While patient education is part of all good clinical care (Suter & Suter, 2008), it may be particularly important for depression and depression treatment, as both are subject to myths, preconceptions, misinformation, and stigma. The more patients and families know what depression is, what causes it and how to treat it, the more likely they will follow the prescribed medication or psychotherapy plan, monitor symptoms and communicate their progress to clinicians.

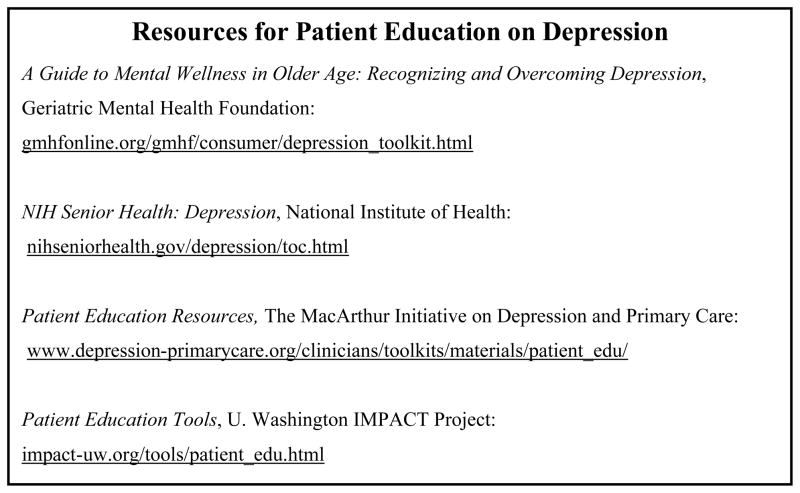

Some of the most frequently asked questions from patients and family members include: What makes you think I’m depressed? What are the signs of serious depression? What causes depression? How do you treat depression? Clinicians are encouraged to use patient education handouts to convey information about the clinical manifestation of depression, the underlying biology, known risk factors, and treatment options in a straightforward way. Figure 5 lists some of the many sources of free patient depression educational materials.

Figure 5.

Resources for Patient Education on Depression

It is important to neither dismiss their symptoms or try to ‘cheer patients up’ with the expectation that symptoms will go away that easily. Helping patients understand that depression is a medical illness, not a character flaw or a condition that they have brought upon themselves, is especially important. At the same time, patients will benefit from reminders that depression is treatable and that treatment works best when patients are adherent and participate in goal setting (described below). Thus there is reason for patients to be hopeful.

Although depression is becoming better understood in society as a whole, many people still have misconceptions about depression that make patient education more challenging, but also more important. On the one hand, some people believe that depression is a ‘normal’ or ‘inevitable’ part of the aging process, especially with older adults who experience significant medical illness, disability, or loss. While these factors can contribute to the risk of depression, they do not mean that living with depression is necessary. Conversely, some people consider depression a character flaw or somehow self-inflicted so that patients merely need to ‘buck up’ to relieve themselves from depression. Again, helping patients understand that depression is real, that they are not responsible for being depressed, that depression is treatable, and that they can help in the treatment process will contribute significantly to the recovery process (Ayalon, Arean, & Alvidrez, 2005; Sirey, Bruce, & Kales, 2010).

e. Patients Goal Setting

While a home healthcare clinician is not a psychotherapist, nor expected to function as one, assisting patients in setting goals is consistent within routine practice. Goal setting is particularly important to depression care as it serves to activate patients, a process that in and of itself has therapeutic value. Evidence from both home healthcare and primary care demonstrates that even with patients who are homebound, in pain, or disabled, activating patients through goal setting is both possible and effective (Dobscha et al., 2009; Kroenke et al., 2009; Scott, Setter-Kline, & Britton, 2004). We recommend that clinicians assist patients in setting goals for self care, pleasurable activities, and social contact. Clinicians should review these goals with patients at each visit by discussing their progress and/or revising their goals.

More specifically, clinicians should encourage patients to take as much responsibility as possible for their self care, including eating a healthy diet, maintaining personal hygiene, and participating in their physical therapy regimen. They should help patients plan daily pleasurable activities such as reading, watching videos, listening to music, doing puzzles or engaging in hobbies they enjoy. Finally, clinicians should remind patients to stay connected to friends and family. They should take time to call people on the phone or video chat, email, have talks with friends and spend time with their families.

CONCLUSION

Many older medical and surgical home care patients experience depressive symptoms that are clinically significant depression. These patients, their families, and clinicians will benefit from clinical care that manages depression as much as care for other chronic illnesses. The Depression CARE for PATients at Home (Depression CAREPATH) intervention was developed to provide the home care clinician skills and procedures needed to include depression care management in routine practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors express appreciation for the guidance and participation of partnering certified home healthcare agencies in the development of the protocols, Dominican Family Health Services (Ossining, NY), Visiting Nurse Association of Hudson Valley (Tarrytown, NY), and Visiting Nurse Services in Westchester (White Plains, NY).

This work was supported by funding from the National Institute of Mental Health grants R01MH082425, MH082425-S1, and R24MH064608 to Dr. Bruce, K01MH073783 to Dr. Sheeran, and the New York State Health Foundation to Dr. Bruce

Contributor Information

Martha L. Bruce, Department of Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College, White Plains, NY

Patrick J. Raue, Department of Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College, White Plains, NY

Thomas Sheeran, Rhode Island Hospital and The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI

Catherine Reilly, Department of Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College, White Plains, NY.

Judith C. Pomerantz, Consultant for Weill Cornell Medical College, White Plains, NY

Barnett S. Meyers, Department of Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College and New York Presbyterian Hospital – Westchester Division.

Mark I. Weinberger, Department of Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College, White Plains, NY.

Diane Zukowski, Triumph Home Health Care, Livonia, MI.

References

- Ayalon L, Arean PA, Alvidrez J. Adherence to antidepressant medications in black and Latino elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(7):572–580. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.7.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EL, McAvay G, Raue PJ, Moses S, Bruce ML. Recognition of depression among elderly recipients of home care services. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(2):208–213. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EL, Raue PJ, Klimstra S, Mlodzianowski AE, Greenberg RL, Bruce ML. An intervention to improve nurse-physician communication in depression care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(6):483–490. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181bf9efa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML, Brown EL, Raue PJ, Mlodzianowski AE, Meyers BS, Leon AC, Heo M, Byers AL, Greenberg RL, Rinder S, Katt W, Nassisi P. A randomized trial of depression assessment intervention in home health care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(11):1793–1800. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML, McAvay GJ, Raue PJ, Brown EL, Meyers BS, Keohane DJ, Jagoda DR, Weber C. Major depression in elderly home health care patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(8):1367–1374. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson VB, Vanderhorst KJ. OASIS-C, depression screening, and M1730: additional screening is necessary: the value of using standardized assessments. Home Healthc Nurse. 2010;28(3):183–190. doi: 10.1097/01.NHH.0000369771.34032.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. OASIS-C Guidance Manual for 2010 Implementation. 2009;Chapter 3:J-4. [Google Scholar]

- Dobscha SK, Corson K, Perrin NA, Hanson GC, Leibowitz RQ, Doak MN, Dickinson KC, Sullivan MD, Gerrity MS. Collaborative care for chronic pain in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. Jama. 2009;301(12):1242–1252. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ell K, Unutzer J, Aranda M, Sanchez K, Lee PJ. Routine PHQ-9 depression screening in home health care: depression, prevalence, clinical and treatment characteristics and screening implementation. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2005;24(4):1–19. doi: 10.1300/J027v24n04_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman PH, Totten AM, Foust J, Naik D, Costello B, Kurtzman E, McDonald M. Medication management: evidence brief. Center for Home Care Policy & Research. Home Healthc Nurse. 2009;27(6):379–386. doi: 10.1097/01.NHH.0000356831.11843.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Bair MJ, Damush TM, Wu J, Hoke S, Sutherland J, Tu W. Optimized antidepressant therapy and pain self-management in primary care patients with depression and musculoskeletal pain: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2009;301(20):2099–2110. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe B, Kroenke K, Grafe K. Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2) J Psychosom Res. 2005;58(2):163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M. National patterns in antidepressant treatment by psychiatrists and general medical providers: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(7):1064–1074. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott LD, Setter-Kline K, Britton AS. The effects of nursing interventions to enhance mental health and quality of life among individuals with heart failure. Appl Nurs Res. 2004;17(4):248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao H, Peng T, Bruce ML, Bao Y. Diagnosed depression among older patients receiving home healthcare: prevalence and key profiles. Psychiatric Services; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran T, Reilly CF, Raue PJ, Weinberger MI, Pomerantz J, Bruce ML. The PHQ-2 on OASIS-C: a new resource for identifying geriatric depression among home health patients. Home Healthc Nurse. 2010;28(2):92–102. doi: 10.1097/NHH.0b013e3181cb560f. quiz 102–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirey J, Bruce ML, Kales HC. Improving Antidepressant Adherence and Depression Outcomes in Primary Care: The Treatment Initiation and Participation (TIP) Program. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(6):554–562. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181cdeb7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter P, Suter WN, Johnston D. Depression revealed: the need for screening, treatment, and monitoring. Home Healthc Nurse. 2008;26(9):543–550. doi: 10.1097/01.NHH.0000338514.85323.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter PM, Suter WN. Patient education. Timeless principles of learning: a solid foundation for enhancing chronic disease self-management. Home Healthc Nurse. 2008;26(2):82–88. doi: 10.1097/01.NHH.0000311024.11023.09. quiz 89–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]