Abstract

Intelligibility of narrowband speech declines considerably at high intensities, but substantial recovery from this “rollover” occurs when flanking noise bands are added. The present study employed two types of added noise: narrowband noise matching the spectral limits of the rectangular speech band (producing within band masking) versus broadband noise (producing within band masking plus simultaneous enhancement by out of band noise components). When noise added to diotic speech in experiment 1 was interaurally uncorrelated rather than diotic, intelligibility increased 5%, regardless of noise bandwidth. Interestingly, regardless of interaural correlation, intelligibility was 13% higher with broadband rather than narrowband noise, indicating that noise induced recovery from rollover precedes binaural processing. In experiment 2, diotic noise was presented either continuously or gated on and off with individual sentences. Intelligibility was 5% higher with continuous noise, showing adaptation of masking, which occurred regardless of noise bandwidth. Moreover, intelligibility was about 11% higher with broadband rather than narrowband noise, regardless of gating, ruling out peripheral adaptation as a source of recovery from rollover. These and other findings discussed are consistent with previous suggestions that intelligibility at high intensities is preserved by inhibition of rate-saturated auditory nerve input to secondary neurons of the cochlear nucleus.

INTRODUCTION

The ability to perceive speech accurately at high intensities poses an interesting puzzle for hearing theory. The majority of auditory-nerve (AN) fibers reach their firing-rate limits at conversational speech levels of about 65 dB, and at higher intensities are unable to provide a rate-based encoding of either the fine spectral details (Sachs & Young, 1979) or rapid amplitude fluctuations (Palmer & Evans, 1979) that form critical features of speech. However, intelligibility may remain nearly perfect at intensities exceeding 90 dB (e.g., Studebaker, Sherbecoe, McDaniel, & Gwaltney, 1999). Viemeister (1983) has provided behavioral evidence indicating that the dynamic range for rate-based intensity discrimination extends to at least 100 dB, and he has offered a theoretical account of encoding at high intensities, which relies upon firing-rate information provided by a small population of AN fibers known to have high thresholds and wide dynamic ranges. This small population of fibers can account for rate-based intensity processing at the upper end of the dynamic range, if it is assumed that input from the larger population of readily saturated, low-threshold fibers is excluded from analysis at high signal intensities (Siebert, 1968; Viemeister, 1983). Physiological models of this exclusionary process (Eriksson & Robert, 1999; Winslow, Barta, & Sachs, 1987) propose that lateral inhibitory interactions in the cochlear nucleus (CN) may selectively attenuate input from low-threshold AN fibers, and consequently produce a shift in the weighting of rate-based intensity analysis to favor input from high-threshold fibers at high signal levels, as required by Viemeister’s (1983) rate-based account of intensity discrimination at the upper end of the dynamic range.

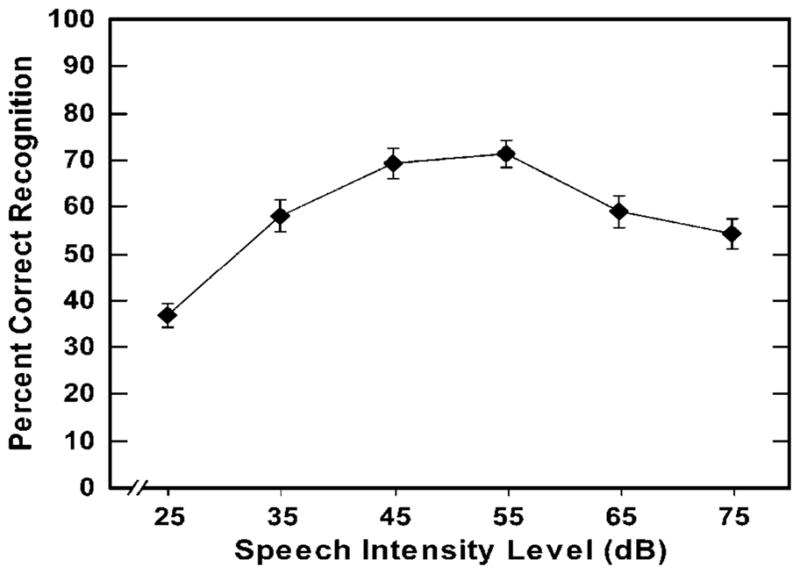

In a previous study, Bashford, Warren and Lenz (2005) tested predictions from this lateral inhibition hypothesis, using a steeply filtered 2/3-octave band of speech (“everyday” sentences) centered at 1500 Hz. As predicted, the narrow speech band was more vulnerable than broadband speech to a decline, or “rollover” of intelligibility as intensity was increased [F(5,125) = 26.1, p<.0001], with a significant loss at 65 dB and greater loss at 75 dB (see Figure 1 below). This rollover at moderate signal levels was presumed to be due to the absence of lateral inhibition that would normally be evoked by speech spectrally adjacent to the 2/3-octave band.

Figure 1.

The mean percent intelligibility scores and standard errors for 2/3-octave narrowband sentences (1500 Hz center frequency) presented at slow-rms peak levels ranging from 25 to 75 dBA. From Bashford et al. (2005), Experiment 1.

Bashford et al. (2005) then tested the conjoint prediction that adding out-of-band white noise (see Fig. 2) would restore intelligibility of the speech band, but only at a speech intensity producing rollover. As predicted, adding flanking bands of white noise (at relative spectrum levels of −40 to −20 dB) enhanced intelligibility for speech presented at slow-rms peak levels of 75 dB but not 45 dB (see Fig. 3).

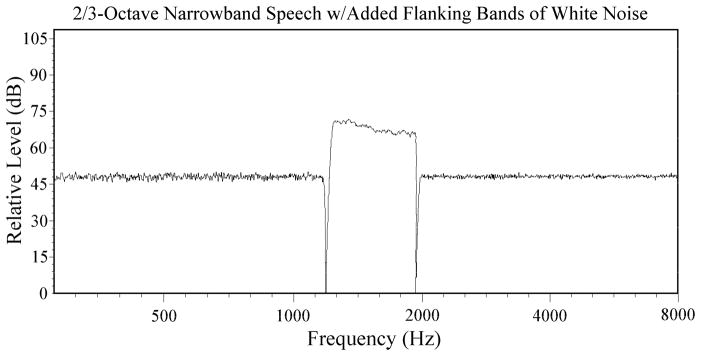

Figure 2.

Spectral plot of stimuli used by Bashford et al. (2005) Experiment 2. A 2/3-octave rectangular band of everyday sentences was presented either alone or along with flanking bands of white noise.

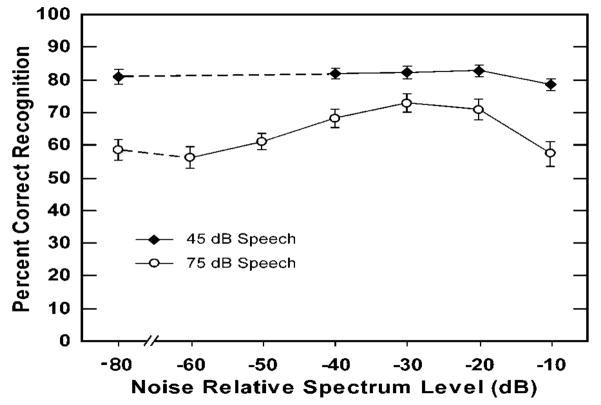

Figure 3.

Mean percent intelligibility scores and standard errors for 2/3-octave narrowband sentences presented at slow-rms peak levels of 45 dBA vs 75 dBA. The narrowband sentences were presented both alone and along with flanking bands of white noise at spectrum levels ranging from −60 to −10 dB relative to the speech band spectrum-level (−60 & −50 dB noise levels were omitted for 45 dB speech due to inaudibility).

The present study extends these earlier findings with three experiments designed to potentially refute the hypothesis that the reduction of intelligibility rollover produced by flanking noise is due to lateral inhibitory interactions within the cochlear nucleus (CN). Experiment 1 contrasted the effects of gated vs. continuous flanking noise to test for the more peripheral effect of firing-rate adaptation in AN fibers, which might be produced by out-of-band noise through the spread activation to fibers responsive to frequencies within the speech pass-band. Experiments 2 and 3 examined possible influences of processing having origins more central than the CN. Experiment 2 used an MLD paradigm to examine the influence of binaural processing (attributed to the superior olivary complex) upon rollover reduction, and Experiment 3 contrasted the effects of ipsilateral vs. contralateral flanking noise upon the intelligibility of a monaurally presented high-intensity speech band to examine the possible role of outer haircell (i.e., cochlear-amplifier) inhibition via by the medial olivocochlear efferent pathway. To foreshadow, uniformly negative findings from these experiments can provide additional support for the CN lateral inhibition hypothesis proposed by Winslow et al. (1987) and Eriksson & Robert, (1999).

METHOD

Subjects

The 85 listeners in this study (2 groups of 30 and one group of 25) were undergraduate students at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee who were paid for their participation. They ranged in age from 18 to 28 and were native monolingual English speakers who reported having no hearing problems and had normal bilateral hearing, as measured by pure tone thresholds of 20 dB HL or better at octave frequencies from 250 to 8,000 Hz.

Stimuli

The formal test stimuli were the 100 (10 lists of 10) CID “everyday” sentences (Silverman and Hirsh, 1955). They were derived from a broadband digital recording (44.1 kHz sampling, 16-bit quantization) used previously by Warren et al. (1995) in a preliminary study of spectral redundancy. An additional 25 practice sentences were drawn from the high-predictability sublist of the revised Speech Perception in Noise (SPIN) test (Bilger, Nuetzel, Rabinowitz, and Rzeczkowski, 1984; Kalikow, Stevens, and Elliott, 1977). The recordings were produced by the same male speaker who has no evident regional accent and an average voicing frequency of 100 Hz.

Prior to filtering, the sentences were transduced by a Sennheiser HD 250 Linear II headphone and their slow-rms peak levels were matched to within 0.2 dBA using a flat-plate coupler in conjunction with a Brüel and Kjaer model 2230 digital sound-level meter set at A-scale weighting (as were all level measurements reported). The sentences were then passed through two successive stages of 4000-order band-pass FIR filtering, using the fir1 function in MATLAB, to produce a 2/3-octave narrow band of speech, centered at 1500 Hz (passband from 1191 Hz to 1890 Hz), with both low-pass and high-pass filter slopes exceeding 3000 dB/octave. White noise, low-pass filtered at 20 kHz, was used to produce the three added-noise conditions employed in the study. They were: 1) flanking bands of low-pass and high-pass filtered noise, providing out-of-band stimulation; 2) Narrowband noise matching the spectral limits of the speech band and providing within-band stimulation; and 3) broadband noise, providing both within-band and out-of-band stimulation. The flanking bands of low-pass and high-pass noise were each produced through two successive stages of 4000-order FIR filtering, as with the speech band. The low-frequency limit of the lower flanking band and the high-frequency limit of the higher flanking band matched those of the broadband noise.

Separate pairs of flanking noise bands were prepared for each noise spectrum-level employed in the present study (−10, −20, and −30 dB relative to the speech spectrum-level). Noise cutoff-frequencies for each pair were adjusted so that the filter skirts of the flanking noise bands would intersect the skirts of the speech band at an average level 60-dB below that of the speech cutoff frequencies. A similar procedure was followed in preparing the narrowband noise that matched the spectral limits of the speech band: White noise was passed through two stages of 4000-order FIR bandpass filtering, with cutoffs adjusted so that the transitions bands of the noise covered those of the speech band.

General Procedure

The design of each experiment incorporated repeated measures. Before receiving a given stimulus condition listeners were presented with several practice sentences, which were first presented broadband and then presented band-pass filtered, along with noise when appropriate, in the same manner as the test sentences that followed. The different experimental conditions presented to a given group of listeners were assigned to separate sets of the “everyday” test sentences. This assignment varied pseudorandomly, so that, across listeners in a group, each condition was applied an equal number of times to each set of sentences. Testing was performed in a sound-attenuating chamber, with the stimuli delivered through Sennheiser HD 250 Linear II Headphones. Listeners were instructed to call out what the voice was saying as best they could, and were encouraged to guess when unsure.

EXPERIMENT 1: Effects of Noise Gating upon Within-Band Masking vs. Out-of-Band Enhancement of High-Intensity Speech-Band Intelligibility

Given the spread of excitation that could be produced by flanking noise bands, it is possible that some of the observed reduction of rollover observed by Bashford et al., (2005) may have been due to noise stimulation within the frequency range of the speech band. Since the noise was presented continuously in those experiments, both during and between stimulus sentence presentations, within-band stimulation by the noise may have produced firing-rate adaptation in AN fibers, and shifted their operating ranges to include higher signal levels (e.g., Gibson, Young, & Costalupes, 1985). To examine this possible peripheral effect upon rollover, listeners in Experiment 1 received the rectangular band of everyday sentences (2/3-octave centered at 1500 Hz) along with white noise stimuli that were presented continuously on half of the experimental trials and on the remaining trials were gated on and off with the sentences to reduce adaptation. Peak levels of the sentences were 75 dB SPL and the noise stimuli were presented at a spectrum level of −20 dB relative to the speech. For half of the trials in both the gated and continuous noise conditions, speech was accompanied by narrowband noise matching its spectral limits (and producing within-band masking). During the remaining trials the speech band was presented along with broadband noise (producing both within-band masking and potential enhancement of intelligibility by out-of-band noise components). The spectra of these stimulus conditions are shown in Figure 4 below. Gating was expected to reduce the extent of firing-rate adaptation to the noise, and thus increase within-band masking and thereby decrease intelligibility relative to the continuous noise condition. This reduction of intelligibility was expected to occur in both the narrowband and broadband noise conditions. Under the assumption that the reduction of rollover produced by out-of-band noise is due to lateral inhibition in the cochlear nucleus, rather than peripheral adaptation of AN fibers, gating was not expected to effect the enhancement of intelligibility by out-of-band noise. Hence it was predicted that the effects of gating and noise bandwidth would not interact. The speech and noise stimuli were presented diotically to the 30 listeners in this experiment.

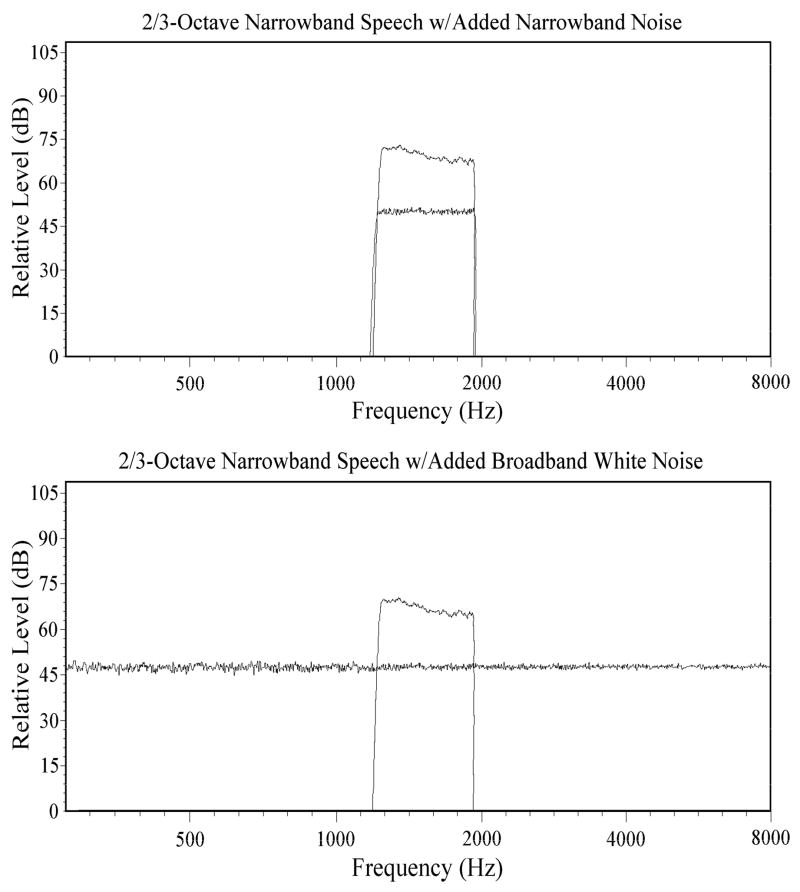

Figure 4.

Spectral plots of stimulus conditions used in both Experiments 1 and 2. Narrowband speech (2/3-octave, 1500 Hz center frequency) was presented along with either narrowband noise having the same spectral limits or broadband noise.

Results

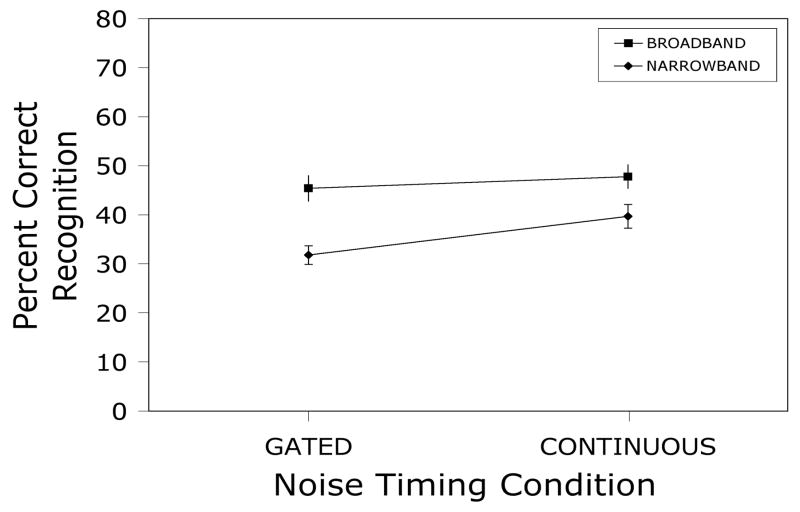

Figure 5 below presents the percent correct recognition scores obtained in Experiment 1.

Figure 5.

Mean percent intelligibility scores and standard errors for 2/3-octave narrowband sentences presented at slow-rms peak levels of 75 dBA along with either broadband or narrowband white noise at −20 dB spectrum level relative to the speech. Noise was continuous on half of the trials and gated on and off with the sentences on the remaining trials.

A repeated measures factorial analysis of variance yielded significant main effects of noise bandwidth [F(1,29) = 22.7, p < .0001] and gating [F(1,29) = 8.7, p < .01], and a nonsignificant interaction [F(1,29) = 1.7, p > .20]. Intelligibility in the broadband noise condition was about 11% higher than in the narrowband noise condition, regardless of gating, and intelligibility in the continuous noise condition averaged about 5% higher than in the gated noise condition, regardless of noise bandwidth. Hence, it appears that firing-rate adaptation in AN fibers is not responsible for the reduction of rollover produced by out-of-band noise.

EXPERIMENT 2: Effects of Noise Interaural Correlation upon Within-Band Masking vs. Out-of-Band Enhancement of High-Intensity Speech-Band Intelligibility

For the 30 listeners in this experiment, the narrowband and broadband noise were always presented continuously. However, the noise stimuli added to the diotic speech band were only diotic (i.e., interaurally identical) in half of the experimental trials, and in the remaining trials were interaurally uncorrelated. It was expected that interaural decorrelation of the noise added to the diotic speech would produce a binaural release from masking exerted by the within-band noise components in both the narrowband and broadband noise conditions. However, because binaural processing occurs at levels above CN, beginning in the superior olivary complex (SOC), it also was predicted that interaural noise decorrelation would not effect the intelligibility enhancement (i.e., recovery from rollover) evoked by the out-of-band noise components in the broadband noise condition. Hence, noise bandwidth and interaural correlation effects were predicted not to interact.

Results

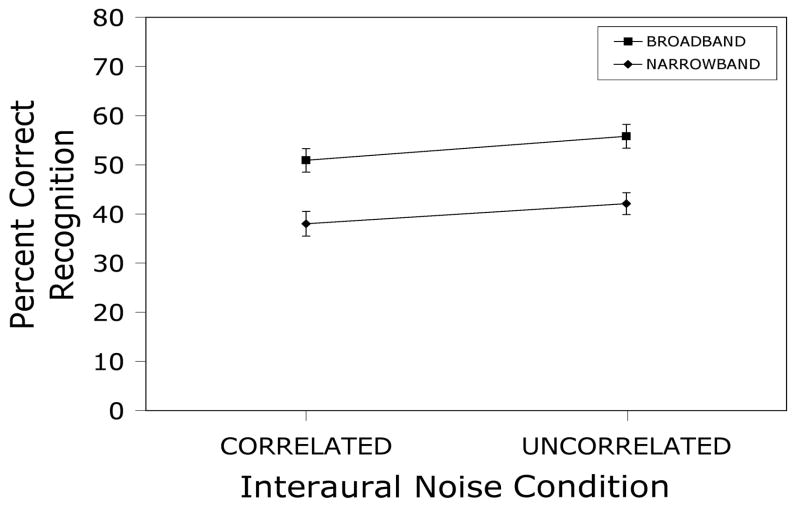

The results plotted in figure 6 conform to predictions. Analysis of variance for data from the four noise conditions yielded significant main effects of bandwidth [F(1,29) = 34.8, p < .0001] and noise interaural correlation [F(1,29) = 5.3, p < .0002], and a nonsignificant interaction of those effects [F(1,29) = .03, p > .80]. Intelligibility in the broadband noise condition was about 13% higher than in the narrowband noise condition, regardless of noise correlation, and intelligibility in the uncorrelated noise conditions was about 5% higher than in the correlated noise conditions, regardless of noise bandwidth. Hence, the results of this experiment clearly indicate that the out-of-band enhancement effect occurs prior to binaural processing in the SOC.

Figure 6.

Mean percent intelligibility scores and standard errors for 2/3-octave narrowband sentences presented at slow-rms peak levels of 75 dBA along with either broadband or narrowband white noise at −20 dB spectrum level relative to the speech. Speech and noise were diotic on half of the trials. On the remaining trials the noise was interaurally uncorrelated.

EXPERIMENT 3: Is recovery from rollover influenced by the medial olivocochlear efferent system: Effects of added ipsilateral vs. contralateral flanking noise upon the intelligibility of high intensity speech

The results of Experiment 2 indicate that the recovery from rollover produced by out-of-band noise occurs prior to binaural processing in the SOC. This provides support for the CN-inhibition hypothesis, but it is possible that processing both central to the CN, in the medial olivocochlear bundle, and peripheral to the CN as well, in the cochlea, may be involved. Specifically, flanking bands of noise may reduce rate saturation of AN fibers by evoking the direct inhibition of outer haircell activity (i.e., the cochlear amplifier) known to be produced by the medial olivocochlear (MOC) reflex system. Fortunately, this hypothesis is readily tested. Since the MOC reflex can be elicited with approximately equal strength by ipsilateral or contralateral stimulation (Guinan, 2006), Experiment 3 presented the 75-dB speech band monaurally to 25 listeners along with contralateral flanking bands of white noise at three spectrum levels relative to the speech: −30, −20, and −10 dB. There was also a no-noise baseline condition as well as a condition delivering the flanking noise bands ipsilaterally at a spectrum level of −30 dB.

Results

The results of Experiment 3 indicate that the MOC reflex is not likely to be involved in the control of rollover. A one-way repeated measures ANOVA yielded a significant main effect of noise condition [F(4,96) = 3.78, p < 0.01], and subsequent Tukey HSD tests (p < 0.05) indicated that only the ipsilateral flanking noise bands improved intelligibility relative to the no-noise baseline condition (64.6% vs. 57.5%). Intelligibility in the contralateral noise band conditions ranged from 55.7 to 57.6 and did not differ significantly.

CONCLUSIONS

The present experiments appear to rule out two processes central to the cochlear nucleus and two more peripheral processes as well: AN fiber firing-rate adaptation and OHC inhibition via the MOC reflex system. Thus it appears likely that neural inhibition in the cochlear nucleus is the primary contributor to the preservation of speech intelligibility at high intensities.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Grant Number R01DC000208 from the National Institute On Deafness And Other Communication Disorders. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute On Deafness And Other Communication Disorders or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Bashford JA, Jr, Warren RM, Lenz PW. Enhancing intelligibility of narrowband speech with out-of-band noise: Evidence for lateral suppression at high-normal Intensity. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2005;117:365–369. doi: 10.1121/1.1835513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilger RC, Nuetzel JM, Rabinowitz WM, Rzeczkowski C. Standardization of a test of speech perception in noise. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1984;27:32–48. doi: 10.1044/jshr.2701.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson JL, Robert A. The representation of pure tones and noise in a model of cochlear nucleus neurons. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1999;106:1865–1879. doi: 10.1121/1.427936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson DJ, Young ED, Costalupes JA. Similarity of dynamic range adjustment in auditory nerve and cochlear nuclei. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1985;53:940–958. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.53.4.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinan JJ., Jr Olivocochlear Efferents: Anatomy, Physiology, Function, and the Measurement of Efferent Effects in Humans. Ear & Hearing. 2006;27:589–607. doi: 10.1097/01.aud.0000240507.83072.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalikow DN, Stevens KN, Elliott LL. Development of a test of speech intelligibility in noise using sentence materials with controlled word predictability. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1977;61:1337–1351. doi: 10.1121/1.381436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer AR, Evans EF. On the peripheral coding of the leve of individual frequency components of complex sounds at high levels. Experimental Brain Research, Supplement. 1979;2:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rhode WS, Greenberg S. Lateral suppression and inhibition in the cochlear nucleus of the cat. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994;71:493–514. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.2.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs MB, Young ED. Encoding of steady-state vowels. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1979;66:470–479. doi: 10.1121/1.383098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebert WM. Stimulus transformations in the peripheral auditory system. In: Kolers PA, Eden M, editors. Recognizing patterns. Cambridge MA: MIT Press; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman SR, Hirsh IJ. Problems related to the use of speech in clinical audiometry. Annals of Otology, Rhinology, & Laryngology. 1955;64:1234–1245. doi: 10.1177/000348945506400424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studebaker GA, Sherbecoe RL, McDaniel DM, Gwaltney CA. Monosyllabic word recognition at higher-than-normal speech and noise levels. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1999;105:2431–2444. doi: 10.1121/1.426848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viemeister NF. Auditory intensity discrimination at high frequencies in the presence of noise. Science. 1983;221:1206–1207. doi: 10.1126/science.6612337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]