Abstract

Background

The asthma-associated gene urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) may be involved in epithelial repair and airway remodelling. These processes are not adequately targeted by existing asthma therapies. A fuller understanding of the pathways involved in remodelling may lead to development of new therapeutic opportunities. uPAR expression in the lung epithelium of normal subjects and patients with asthma was investigated and the contribution of uPAR to epithelial wound repair in vitro was studied using primary bronchial epithelial cells (NHBECs).

Methods

Bronchial biopsy sections from normal subjects and patients with asthma were immunostained for uPAR. NHBECs were used in a scratch wound model to investigate the contribution of the plasminogen pathway to repair. The pathway was targeted via blocking of the interaction between urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) and uPAR and overexpression of uPAR. The rate of wound closure and activation of intracellular signalling pathways and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) were measured.

Results

uPAR expression was significantly increased in the bronchial epithelium of patients with asthma compared with controls. uPAR expression was increased during wound repair in monolayer and air-liquid interface-differentiated NHBEC models. Blocking the uPA–uPAR interaction led to attenuated wound repair via changes in Erk1/2, Akt and p38MAPK signalling. Cells engineered to have raised levels of uPAR showed attenuated repair via sequestration of uPA by soluble uPAR.

Conclusions

The uPAR pathway is required for efficient epithelial wound repair. Increased uPAR expression, as seen in the bronchial epithelium of patients with asthma, leads to attenuated wound repair which may contribute to the development and progression of airway remodelling in asthma. This pathway may therefore represent a potential novel therapeutic target for the treatment of asthma.

Keywords: Asthma, urokinase plasminogen activator receptor, bronchial epithelial cells, wound repair, airway epithelium, asthma genetics, COPD mechanisms, allergic lung disease, asthma pharmacology, COPD exacerbations, COPD pathology, COPD pharmacology, allergic lung disease, asthma genetics

Key messages.

What is the key question?

What is the role of the asthma-associated gene uPAR in epithelial wound repair?

What is the bottom line?

Patients with asthma had increased epithelial uPAR expression. In vitro, increased uPAR expression led to attenuated wound repair, potentially reflecting a mechanism by which uPAR single nucleotide polymorphisms may contribute to decline in lung function and airway remodelling in asthma.

Why read on?

This work helps further our understanding of epithelial repair and airway remodelling, which are potential drug targets for asthma.

Introduction

We have previously identified urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR, PLAUR, CD87) as an asthma-associated gene showing genetic association between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) spanning the uPAR gene (PLAUR) and asthma susceptibility, bronchial hyper-responsiveness (BHR), decline in lung function and plasma/serum levels of uPAR.1 These data suggest that variation at the PLAUR locus may predispose individuals with asthma to accelerated decline in lung function, a marker of airway remodelling.

uPAR is the key receptor in the plasminogen pathway which binds and activates the serine protease urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA, PLAU), leading to an extracellular protease cascade implicated in mechanisms including cell migration, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activation and cytokine release.2 uPAR also coordinates extracellular signals and transfers them to intracellular signalling responses via co-receptors including integrins, leading to changes in processes including proliferation, migration and adhesion.2–4 Soluble and cleaved forms of uPAR shed from the cell surface participate in distinct signalling pathways as well as acting as a decoy receptor preventing uPA binding to surface uPAR.5–7 Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1, SERPINE1) binds to uPA and prevents its activation.8 9 PAI-1 also binds to vitronectin, blocking αVβ3 integrin and uPAR binding, inhibiting cell adhesion and altering migration.10 11

A key feature of asthma (especially severe asthma) is airway remodelling.12 There is growing support for a role of dysregulated or aberrant epithelial repair in this process,13 14 indicating a need to further understand the mechanisms of bronchial epithelial repair. Many of the processes in which the plasminogen pathway is involved are features of epithelial repair and airway remodelling. An in vivo human study investigating bronchial epithelial repair found increased uPA and PAI-1 transcripts in brushings taken 7 days after injury, suggesting that this pathway is involved specifically in epithelial repair processes in the bronchi.15 Another study using a mouse asthma model showed that inhalation of uPA could protect against subepithelial fibrosis and airway hyper-responsiveness,16 indicating that the plasminogen pathway plays a role in airway remodelling.

We hypothesised that genetically predisposed dysregulated expression of uPAR may be a feature of asthma and that uPAR plays a critical role in epithelial repair. We aimed to investigate uPAR expression in normal and asthmatic lung to determine whether uPAR is increased in the epithelium of subjects with asthma. A scratch wound model in primary human bronchial epithelial cells (NHBEC) was used to investigate the role of uPAR and the plasminogen pathway in epithelial wound repair.

Our data support the hypothesis that uPAR is increased in the bronchial epithelium in subjects with asthma, that the interaction between uPA and uPAR is critical for efficient bronchial epithelial wound repair in vitro and that increased expression of uPAR, as observed in asthma, attenuates in vitro repair.

Methods

Immunostaining of bronchial biopsies

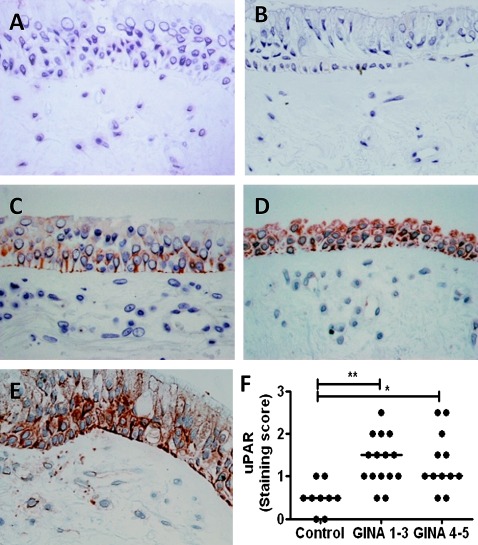

Sections taken from control and asthmatic glycomethacrylate-embedded bronchial biopsies were stained using anti-uPAR (sc-32764, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany) or an appropriate isotype control. A semi-quantitative score of staining was used to define expression in the epithelium (0=none, 1=low, 2=moderate, 3=high; mean of two sections per donor, scored by a blinded observer, figure 1). Patient details and clinical characterisation are shown in the online supplement.

Figure 1.

Urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) is increased in asthmatic bronchial epithelium. Bronchial biopsy sections from controls and subjects with asthma were stained with (A) isotype control or (B–E) anti-uPAR antibody. A semiquantitative staining score of 0=none (B), 1=low (C), 2=moderate (D) or 3=high (E) was applied to each section and two sections were scored per subject. (F) uPAR protein levels were higher in the bronchial epithelium of patients with asthma than in normal controls, irrespective of severity (p=0.002). *p<0.05, **p<0.01. GINA, Global Initiative for Asthma.

Cell culture

NHBEC (Lonza, Wokingham, UK) were used at passage 3–4 in growth factor-supplemented medium (BEGM, Lonza) for monolayer experiments. Cells were differentiated at passage 3 at the air–liquid interface (ALI) according to a previously published method (see online supplement).17 18 Three donors were used in this study (see table E1 in online supplement). Details of wound repair experiments, preparation and transfection of plasmids for overexpression of uPAR are shown in the online supplement.

Immunofluorescence of cultured cells

Monolayer NHBECs were grown on glass chamber slides for immunofluorescence, ALI cultured cells were fixed in situ on inserts and transferred to glass slides for visualisation. The cells were fixed using 4% formaldehyde and permeabilised with 0.15% Triton-X before blocking with 10% goat serum. They were incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight and Alexa488-labelled secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature (table E2 in online supplement). The cells were visualised using the Zeiss spinning disc confocal microscope and Volocity software (Perkin Elmer, Cambridge, UK).

Quantitative PCR

Cultured cells were lysed and RNA was extracted using silica columns (RNeasy mini kit, Qiagen, Crawley, UK). cDNA was synthesised using Superscript II (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) and random hexamer primers according to the manufacturer's instructions. mRNA levels of uPAR, uPA and PAI-1 were quantified using a series of quantitative PCR assays (see table E3 in online supplement). Quantitative PCR was performed using TaqMan gene expression master mix (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK) and HPRT1 endogenous control (Hs01003267_m1, Applied Biosystems) on a Stratagene MxPro3005 machine using 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 60 s. Data were normalised using the housekeeper (HPRT1) and the 2−DCt method.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in 1× SDS loading buffer. Equal volumes of lysates were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. Proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane and probed using a panel of primary antibodies (see table E4 in online supplement) and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Binding was visualised by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, UK). Membranes were stripped using Restore Western blot stripping buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cramlington, UK) and re-probed for loading controls. Densitometry of protein bands used ImageJ 1.41 (NIH, USA http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). For statistical analysis, data were normalised to β-actin and exposure levels.

Analysis of supernatant proteins

DuoSet enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK) were used to quantify soluble uPAR (suPAR), uPA and PAI-1 in cell culture supernatants following the manufacturer's recommendations. Semi-quantitative measurement of MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity was obtained using gelatin zymography (see online supplement). MMP-9 activity was further quantified using the FluorokineE assay (R&D Systems). Plasmin activity in supernatants from ALI cultures was measured using the SensoLyte AFC Plasmin Activity Kit (AnaSpec, Cambridge Bioscience, Cambridge, UK). Plasmin activity in supernatants from monolayer cultures was below the detection limit of this assay.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 5.03 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Semi-quantitative data were analysed using the Mann–Whitney or Kruskal–Wallis tests while quantitative data were analysed using the Student t test or ANOVA with Bonferonni post-test. p<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

uPAR protein levels are increased in asthma bronchial epithelium

Bronchial biopsies were taken from nine normal subjects and 27 individuals with asthma (see table E5 in online supplement). Asthma cases showed a range of severities and were divided into mild to moderate (Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) severity 1–3, n=15) and severe asthmatics (GINA 4–5, n=12).19 Analysis of epithelial immunostaining for uPAR used a semi-quantitative score (figure 1B–E represents scores 0–3 for illustration). Biopsies taken from subjects with asthma showed a significant increase in uPAR levels compared with control subjects, particularly in the epithelial layer (p=0.002); however, there was no difference between subjects with mild to moderate or severe asthma (figure 1F). Subjects with asthma compared with controls showed decreased percentage predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) (not significant) and increased BHR to methacholine (p<0.0001). There was no significant difference between groups for age, gender, atopy, smoking status or smoking pack-years, but there was a trend towards increased smoking in subjects with asthma. The analysis was repeated in non-smokers only and showed similar results (data not shown).

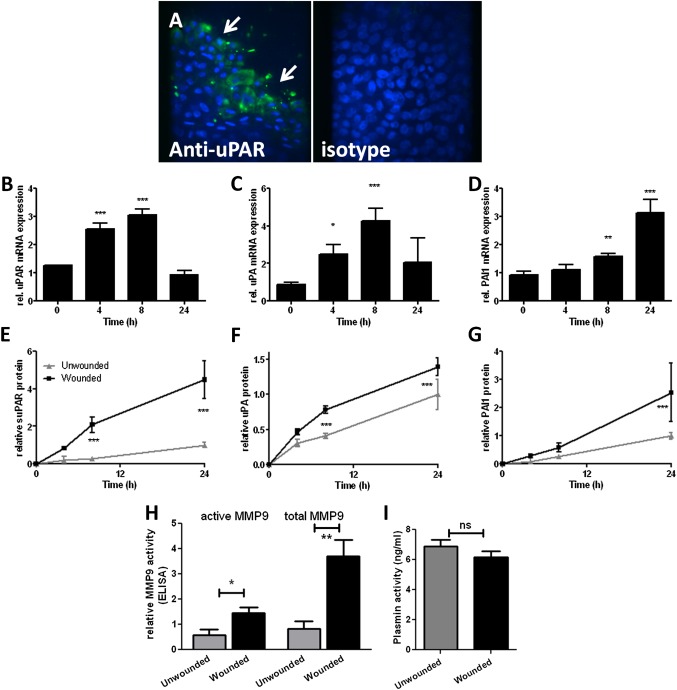

Induction of uPAR is a feature of wound repair in primary NHBECs in vitro

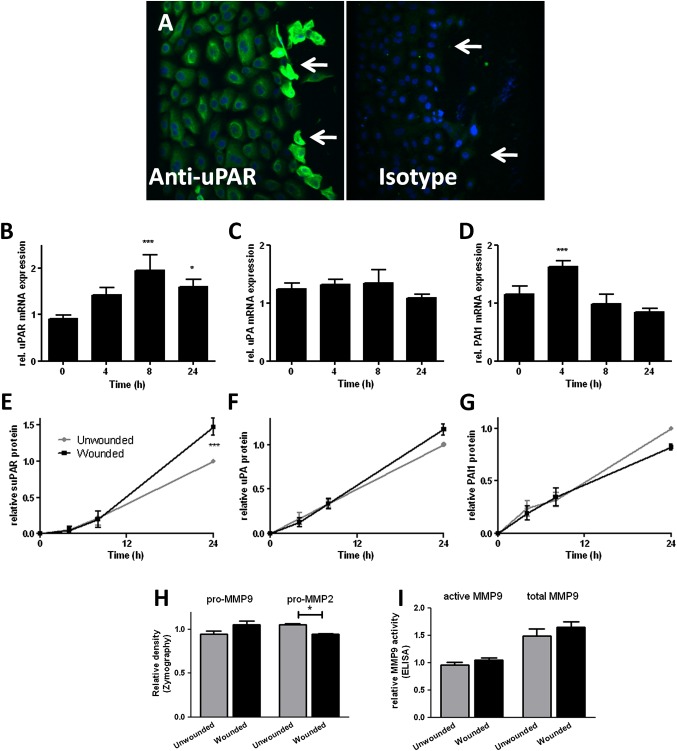

Confluent monolayer NHBEC cultures were scratch wounded and followed until closure over 24 h (n=4; see figure E1A in online supplement). Immunostaining 4 h after wounding showed increased uPAR protein expression in cells at the wound edge (figure 2A). Increased mRNA levels of uPAR (p<0.001 at 8 h, figure 2B) and PAI-1 (p<0.001 at 4 h, figure 2D) but not uPA (figure 2C) were detected during the wound repair process. Wounding increased levels of soluble uPAR (suPAR) in supernatants after wounding (p<0.001 at 24 h, figure 2E). Analysis of MMPs as a marker of plasminogen pathway activity in supernatants taken at 24 h after wounding using two different methods (zymography (figure 2H) and MMP-9 activity assay (figure 2I)) showed that pro-MMP-2 was significantly reduced 24 h after wounding (p=0.03).

Figure 2.

Induction of urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) is a feature of primary bronchial epithelial cell (NHBEC) wound repair. Wound repair in monolayer NHBECs occurs over 24 h (n=4). (A) uPAR expression increases in cells at the wound edge 4 h after wounding (arrows). uPAR (B, E), urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) (C, F) and plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) (D, G) mRNA and protein levels in supernatants measured in wounded/unwounded cells over 24 h. Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and MMP-9 activity measured at 24 h by zymography (H) and ELISA-based MMP-9 activity assay (I). *p<0.05, ***p<0.001.

Blocking the uPA–uPAR interaction attenuates wound repair in primary NHBECs in vitro

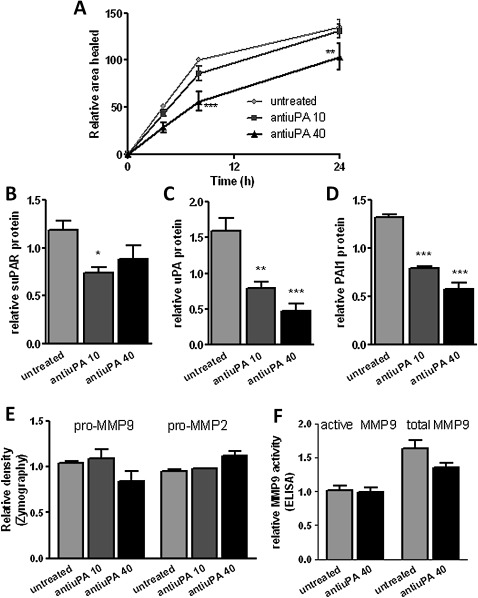

The uPA–uPAR interaction can be blocked using anti-uPA antibody.20–22 This blocking attenuated wound repair in monolayer NHBECs in a dose-dependent manner (p<0.001 at 40 μg/ml, figure 3A, n=4). Isotype control antibody caused a small decrease in the area healed at 24 h only (p<0.01), while an anti-uPAR domain II antibody anticipated not to affect the uPA–uPAR interaction had no effect on wound repair. Anti-uPA-treated cells showed a significantly reduced area healed compared with medium control, isotype control and non-blocking antibody control (data not shown). Addition of blocking antibody at the time of wounding led to lower levels of suPAR (p=0.04, figure 3B), uPA (p<0.001, figure 3C) and PAI-1 (p<0.001, figure 3D) in the supernatants 24 h after wounding. Addition of blocking antibody did not affect MMP-2/MMP-9 expression or MMP-9 activity (figure 3E,F).

Figure 3.

(A) Blocking the interaction between urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) and urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) attenuates the rate of wound repair (n=4). (B) Soluble uPAR (suPAR), (C) uPA and (D) plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) levels decrease in supernatants at 24 h in the presence of blocking antibody. (E) Zymography and (F) an ELISA-based assay detect matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and MMP-9 activity at 24 h. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Blocking the uPA–uPAR interaction alters Erk/Akt/p38MAPK signalling pathways

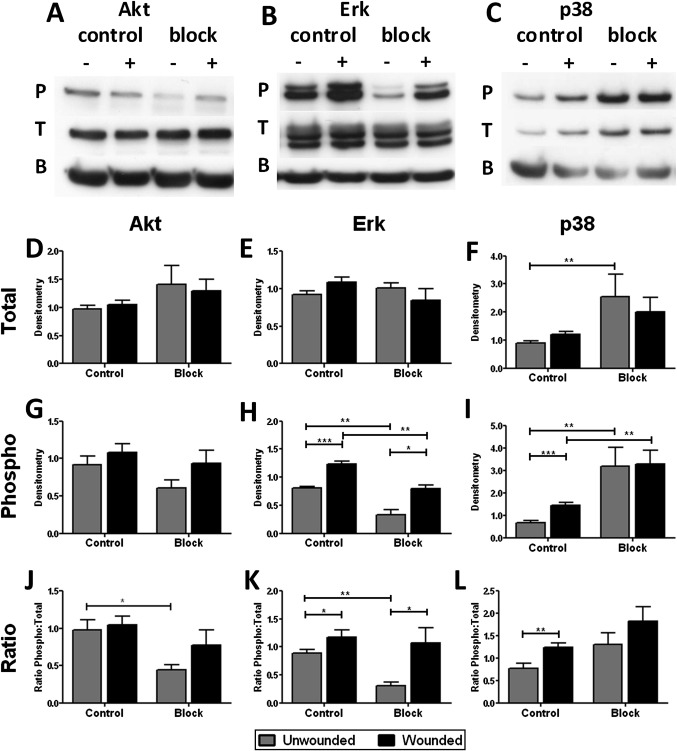

Signalling pathways implicated in wound repair are also downstream of uPAR activation. To investigate these pathways, NHBECs were lysed 5 min after wounding. Cells were also incubated with the anti-uPA blocking antibody at the time of wounding. Western blotting was used to investigate the expression and activation of Akt (figure 4A), Erk1/2 (figure 4B) and p38MAPK (figure 4C) in these samples by measuring phosphorylated and total proteins and the ratio of these forms (representative of n=8 control/untreated, n=4 blocking). In control cells, phosphorylation of Erk1/2 (p<0.001, figure 4H,K) and p38MAPK (p<0.001, figure 4I,L) but not Akt (figure 4G,J) was increased on wounding, with no effect on total protein (figure 4D–F). Addition of blocking antibody caused an increase in total p38 (p=0.004 unwounded, figure 4F). There was also a decrease in phospho-Erk1/2 (p=0.004 unwounded, p=0.004 wounded, figure 4H) and an increase in phospho-p38 (p=0.0081 unwounded, p=0.004 wounded, figure 4I) in both unwounded and wounded cells. Phospho-p38 was not significantly increased on wounding when cells were treated with blocking antibody (figure 4I,L), although there was increased phosphorylation of Akt (figure 4G,J, p=ns) and Erk1/2 (figure 4H,K, p<0.05).

Figure 4.

Blocking the interaction between urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) and urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) alters intracellular signalling. Cells were treated with (block, n=4) or without (control, n=8) blocking antibody and with (+) or without (−) wounding for 5 min. Western blotting was performed for phosphorylated and total protein and β-actin (labelled P, T and B) for (A) Akt, (B) Erk1/2 and (C) p38MAPK; representative blots shown. Densitometry was normalised to β-actin signal and gel intensity for total (D–F) and phosphorylated (G–I) proteins for statistical analysis. The ratio of phosphorylated to total protein was also determined (J–L). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Parallel experiments using a non-blocking isotype-matched anti-uPAR domain II antibody showed no significant effect on signalling compared with untreated cells (data not shown).

Increased uPAR levels lead to receptor shedding and attenuated wound repair

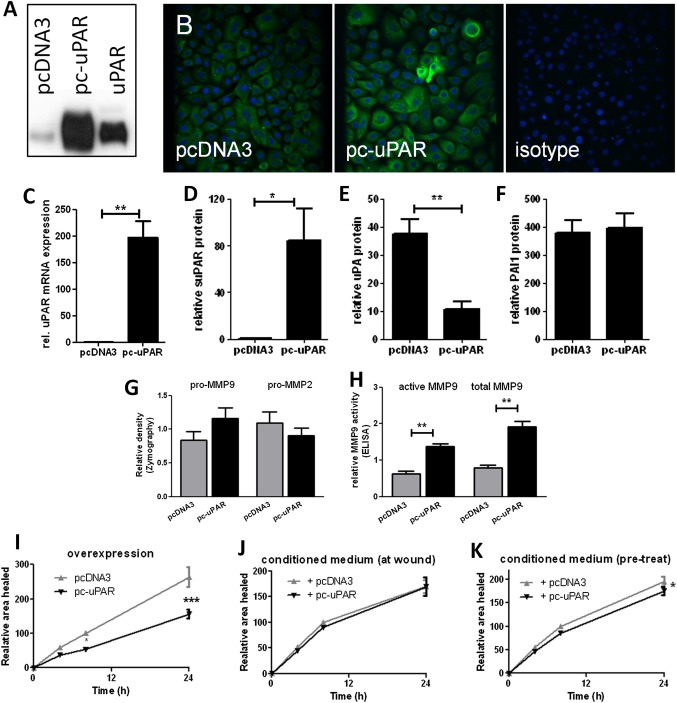

NHBECs were transiently transfected with control (pcDNA3) or membrane uPAR overexpression (pc-uPAR) plasmids. Increased uPAR was confirmed by western blotting (figure 5A, representative of n=3), immunofluorescence (figure 5B) and quantitative PCR (p=0.008, figure 5C). Supernatant suPAR was also significantly increased (p=0.04, figure 5D). Levels of uPA (p=0.004, figure 5E) but not PAI-1 (figure 5F) in supernatants were significantly reduced 24 h after transfection, potentially due to uPA sequestration by suPAR. At baseline (24 h after transfection, prior to wounding), cells overexpressing uPAR showed a trend towards decreased pro-MMP-2 and increased pro-MMP-9 levels by zymography (figure 5G), which was significant in the MMP-9 activity assay (p=0.005 active MMP-9, p<0.001 total MMP-9, figure 5H). Increased uPAR expression attenuated wound repair (p<0.001, n=5, figure 5I). To determine whether this is due to intracellular signalling or soluble factors, conditioned supernatant from control or uPAR overexpressing cells was added to non-transfected cells. Adding back conditioned supernatants at the time of wounding had no significant effect on the rate of repair (figure 5J); however, cells pretreated with uPAR-conditioned supernatants for 24 h showed a small but significant attenuation of repair (p=0.03, figure 5K).

Figure 5.

Increased urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) expression leads to attenuated wound repair. Cells transfected with pc-uPAR show elevated expression by (A) Western blotting with control (uPAR), (B) immunofluorescence and (C) quantitative PCR 24 h after transfection (n=5). Increased soluble uPAR (suPAR) (D), decreased urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) (E) and no change in plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) (F) levels were observed in supernatants. Changes in matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 and MMP-2 levels/activity were detected using (G) zymography and (H) an ELISA-based assay. (I) Cells overexpressing uPAR showed attenuated wound repair. Control cells were treated with supernatants from cells containing pc-DNA3 or pc-uPAR at wounding (J) or 24 h prior to wounding (K) and repair was measured (n ≥4, two donors). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Increased uPAR does not affect Erk/Akt/p38MAPK signalling after wounding

Signalling activation was investigated in cells transfected with pcDNA3 or pc-uPAR. These cells were wounded 24 h after transfection and harvested after a further 5 min (n=3). Measurement of Erk1/2, Akt and p38MAPK showed no significant differences in activation state between the two cell types in unwounded or wounded cells (data not shown).

uPAR induction is a feature of wound repair responses in a differentiated NHBEC model

We analysed uPAR pathway components in an ALI differentiated NHBEC model (representative of n=2). NHBECs were cultured at ALI for 21 days before wounding. This model develops significant transepithelial electrical resistance and expression of markers of ciliated (β-tubulin IV, figure E2A in online supplement) and goblet cells (MUC5AC, figure E2B in online supplement). Cells also developed a network of localised actin staining (see figure E2C in online supplement). Cultures were wounded and repair followed over 24 h (see figure E1B in online supplement). Immunostaining showed increased uPAR expression in cells at the wound edge 4 h after wounding (figure 6A). Expression of uPAR (p<0.001, figure 6B), uPA (p<0.001, figure 6C) and PAI-1 (p<0.001, figure 6D) was increased at the mRNA level during repair. suPAR, uPA and PAI-1 were increased in supernatants from wounded cells (p<0.001, figure 6E–G). MMP-2/MMP-9 were measured in supernatants by zymography (not shown) and MMP-9 activity assay (figure 6H). MMP-2 activity was not always detected by zymography, suggesting relatively low levels of expression; however, there was a trend towards decreased expression in wounded cells (data not shown). MMP-9 was increased in wounded cells (active p=0.03, total p=0.004, figure 6H). Plasmin activity was measured in supernatants at 24 h after wounding. No significant difference in activity between wounded and unwounded cells was detected (figure 6I).

Figure 6.

Induction of urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) is a feature of primary bronchial epithelial cell (NHBEC) wound repair in an air–liquid interface (ALI) differentiated model. Wound repair in differentiated NHBECs occurs over 24 h (representative of n=2). (A) uPAR expression is increased in cells at the wound edge 4 h after wounding (arrows). uPAR (B, E), urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) (C, F) and plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) (D, G) mRNA and protein levels in supernatants were measured in wounded and unwounded cells over 24 h. Matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) (H) and plasmin (I) activity were measured at 24 h. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Discussion

We hypothesised that a predisposition to altered uPAR expression may in part underlie our previously observed genetic association between PLAUR SNPs and asthma susceptibility, BHR and increased decline in lung function in subjects with asthma.1 Using a series of controls and individuals with asthma, we have shown that uPAR expression is increased in the bronchus of subjects with asthma, particularly in the epithelium, but there was no correlation between disease severity and epithelial uPAR staining, possibly due to limited power caused by the population size. In addition, those with more severe disease are treated with high-dose inhaled corticosteroids and/or oral corticosteroids which may confound expression of uPAR. The relationship between uPAR expression in the epithelium and airway remodelling requires further investigation, but relating epithelial histology to uPAR expression in a cross-sectional study would be difficult to interpret and is beyond the scope of this paper. Previous studies have found uPAR levels to be increased in the sputum of patients with asthma23 as well as in lung biopsies from a single individual who died with asthma.24 This is the first study to investigate the expression of uPAR protein ex vivo in the airways of a number of control and asthmatic individuals. These findings provide a basis for further investigation of the role of uPAR in the epithelium. Using primary human NHBECs, we have shown that alterations in the uPAR pathway are a feature of epithelial repair. Blocking the uPA–uPAR interaction attenuates repair while increased uPAR levels, as observed in asthma, also attenuate repair.

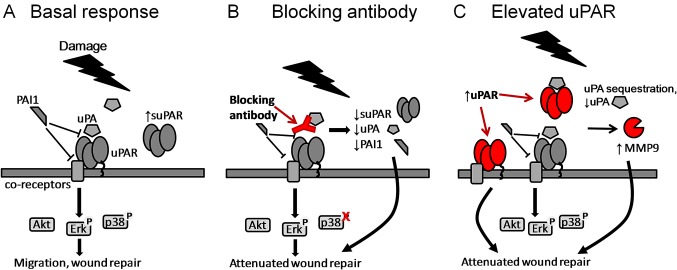

We characterised the expression of uPAR pathway components during primary bronchial epithelial cell wound repair in both monolayer (summarised in figure 7A) and differentiated culture models. The differentiated model consists of pseudostratified cells at ALI,17 18 showing significant transepithelial electrical resistance.25 Cells develop localised actin (replacing the diffuse expression seen in monolayer culture) and develop expression of markers of ciliated and goblet cells, characteristic of the bronchial epithelium in vivo. uPAR and PAI-1 mRNA expression was increased during repair, and uPAR protein expression was increased in cells at the wound edge. There was also a significant increase in suPAR in supernatants of wounded cells in both models. In the ALI model only, uPA mRNA and uPA and PAI-1 in supernatants were also increased. A previous study comparing asthmatic and normal paediatric airway epithelial cells also found increased PAI-1 mRNA and activity during wound repair.26 MMP-2/MMP-9 activation is a potential downstream target of the proteolytic plasmin cascade.27 28 Both MMP-2 and MMP-9 have been shown to promote epithelial migration and wound repair in various models.22 29 30 In monolayer culture, pro-MMP-2 was modestly decreased after wounding. At ALI, MMP-9 activity was increased while pro-MMP-2 was not always detected, suggesting that patterns of MMP activation may differ depending on the model and cell type used. We were not able to detect active forms of MMP-2 and MMP-9 by zymography and MMP-2 activity was not specifically measured, limiting the conclusions that can be drawn about MMP-2 activation in both our wounding models. Differences between the two culture systems may be driven by the different cellular composition present (‘basal’ vs ‘differentiated’) and different culture conditions (wounding vs differentiation medium (see Methods); 6-well plate vs 12-well transwell insert). We consider the use of both culture systems to be a strength of our approach but acknowledge the limitations of direct comparison between the systems.

Figure 7.

Targeting the urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) pathway leads to attenuation of wound repair via different mechanisms. Urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) binding to uPAR activates both extracellular and intracellular signalling cascades. (A) Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) binding to uPAR and its co-receptors interferes with signalling via multiple mechanisms. Damage to the epithelial layer leads to increased soluble uPAR (suPAR) and phosphorylation of Erk1/2 and p38. (B) Blocking the interaction between uPA and uPAR at the time of damage leads to decreased suPAR, uPA and PAI-1 in the supernatant, changes in activation of signalling pathways and attenuation of wound repair. (C) Increased levels of uPAR lead to increased receptor shedding, changes in matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) activity and attenuation of wound repair. Soluble uPAR sequesters uPA and prevents it binding to cell surface uPAR.

uPA–uPAR binding may also trigger intracellular signalling cascades, including PI3-kinase/Akt, p38MAPK and Erk1/231 32 (reviewed by Smith and Marshall4). Previous data from our group and others have shown that these signalling pathways are also involved in epithelial wound repair.18 33 34 We show increased Erk1/2 and p38MAPK but not Akt phosphorylation 5 min after wounding in the monolayer system, suggesting that either Akt is not activated on wound healing in our model or that activation may occur at a different time point. We did not perform this analysis in the ALI model, which is a limitation of the current study.

Blocking the interaction of uPA and uPAR resulted in attenuation of wound repair and reduction in soluble pathway components in cell supernatants (suPAR, uPA and PAI-1), confirming that the uPAR pathway is a component of repair. Various studies have found that increased uPA induces uPA, uPAR and PAI-1 expression in airway epithelial cells via mRNA stabilisation.35 We hypothesise that the binding of uPA by the blocking antibody may have an opposite effect, leading to downregulation of uPAR, uPA and PAI-1. It should be noted that the blocking antibody will compete with the anti-uPA ELISA, therefore the ELISA measurements of uPA may reflect only ‘free’ uPA in the supernatant. MMP-2/MMP-9 levels were not affected by the addition of anti-uPA, suggesting that they are not directly regulated by uPA levels. Treatment of the cells with plasmin or aprotinin (a plasmin inhibitor) did not significantly affect the rate of repair (data not shown). In addition, in the differentiated model, plasmin activity in supernatants was not affected by wounding. These data suggest that attenuation of repair may not be driven by the proteolytic plasmin cascade. Blocking the interaction of uPA and uPAR resulted in changes in intracellular signalling activation (ie, phosphorylation of Erk1/2 and p38MAPK), suggesting that blocking acts via changes in the balance between key intracellular signalling pathways involved in the wound repair response (figure 7B). An isotype control antibody showed some inhibition of wound healing; this effect was not seen using a non-blocking isotype-matched anti-uPAR domain II antibody. The anti-uPAR antibody was therefore used as a control in intracellular signalling experiments, showing no significant effect on cell signalling.

We have shown that uPAR expression is increased in the bronchial epithelium of subjects with asthma. We therefore overexpressed uPAR in the NHBEC model. Transfected cells showed high levels of surface uPAR and suPAR in the supernatant, potentially mimicking the increased levels of uPAR observed in the epithelium and sputum23 of patients with asthma. Increased uPAR levels lead to a significant attenuation of repair which may reflect the previously observed reduced capacity for epithelial repair of asthmatic versus control cells in cell culture.36 Supernatant uPA is significantly decreased 24 h after uPAR overexpression; increased suPAR may sequester uPA, preventing binding to surface uPAR. The soluble receptor may also interact with cell surface molecules and modulate signalling directly.5 6 37 On wounding, signalling activation was unchanged in uPAR over-expressing cells; however, wound repair was attenuated. Overexpression of uPAR also increased baseline MMP-9 activity, suggesting a change in cell phenotype.

Cells pretreated with pc-uPAR-conditioned supernatants showed a reduction in wound healing which was not present when treated at the time of wounding. This change was modest, suggesting that soluble factors may not play a major role in attenuating repair in our model. However, a study in a breast cancer cell line showed that suPAR decreased matrigel invasion only when cells were preincubated for 6–18 h. Similarly, a transwell migration assay with 15 min preincubation showed no effect of suPAR.7 These data support the proposal that suPAR treatment or overexpression may induce an altered phenotype and that changes take time to occur. We hypothesise that overexpression of uPAR results in increased receptor shedding, generating suPAR which sequesters uPA. Signalling via surface uPAR and suPAR modifies the cell phenotype, including increased MMP-9 activity, via as yet unexplored mechanisms to reduce the ability of the cells to respond to repair signals (figure 7C). These changes may be significant for epithelial function in patients with asthma.

Overall, this study shows that uPAR is increased in the bronchial epithelium in asthma and that the uPAR pathway is upregulated during wound repair in primary NHBECs in vitro, both in monolayer culture and a differentiated model. Blocking the interaction between uPA and uPAR attenuates repair via modulation of intracellular kinase cascades, while overexpression of uPAR results in attenuation of wound repair via increased receptor shedding and potential alterations in cell phenotype in vitro. Our data suggest that the interaction between uPA and membrane uPAR is an important stage in the epithelial repair process. A late increase in soluble uPAR may be a feedback loop associated with resolution of repair, with soluble uPAR potentially acting to sequester uPA and prevent its binding to surface uPAR, as suggested in the overexpression model.

In asthma there is increased epithelial expression of uPAR and, importantly, soluble cleaved uPAR (as measured in sputum).23 We have previously shown a genetic association of PLAUR SNPs with increased BHR, increased rate of decline in lung function and increased plasma/serum levels of uPAR in patients with asthma.1 The current data support the hypothesis that patients with asthma may be genetically predisposed to increased uPAR expression, so this feedback loop may be sustained in asthma, ultimately leading to disruption of bronchial epithelial repair homeostasis which may be a factor in the development of airway remodelling and increased decline in lung function. The uPA–uPAR axis may therefore be a novel therapeutic opportunity to target these mechanisms, which are not adequately addressed by existing drugs in asthma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs Charlotte Billington and Tim Self for confocal imaging assistance and Dr William Chang for assistance and standard curve data for zymography. We acknowledge useful discussion with Dr Christine Pullar (University of Leicester) regarding the wounding model.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was funded by Asthma UK Grant 08/017, CEB Wellcome Trust Senior Fellowship.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Leicestershire ethics committees.

Contributors: IS conceived and designed the study. CES performed in vitro work, statistical analysis and drafted the article. HSN performed some in vitro work. CEB generated ex vivo patient data. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Barton SJ, Koppelman GH, Vonk JM, et al. PLAUR polymorphisms are associated with asthma, PLAUR levels, and lung function decline. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;123:1391–400e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blasi F, Sidenius N. The urokinase receptor: focused cell surface proteolysis, cell adhesion and signaling. FEBS Lett 2010;584:1923–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blasi F, Carmeliet P. uPAR: a versatile signalling orchestrator. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2002;3:932–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith HW, Marshall CJ. Regulation of cell signalling by uPAR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010;11:23–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Resnati M, Guttinger M, Valcamonica S, et al. Proteolytic cleavage of the urokinase receptor substitutes for the agonist-induced chemotactic effect. EMBO J 1996;15:1572–82 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Resnati M, Pallavicini I, Wang JM, et al. The fibrinolytic receptor for urokinase activates the G protein-coupled chemotactic receptor FPRL1/LXA4R. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99:1359–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jo M, Thomas KS, Wu L, et al. Soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor inhibits cancer cell growth and invasion by direct urokinase-independent effects on cell signaling. J Biol Chem 2003;278:46692–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mignatti P, Rifkin DB. Nonenzymatic interactions between proteinases and the cell surface: novel roles in normal and malignant cell physiology. Adv Cancer Res 2000;78:103–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellis V, Wun TC, Behrendt N, et al. Inhibition of receptor-bound urokinase by plasminogen-activator inhibitors. J Biol Chem 1990;265:9904–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stefansson S, Lawrence DA, Argraves WS. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and vitronectin promote the cellular clearance of thrombin by low density lipoprotein receptor-related proteins 1 and 2. J Biol Chem 1996;271:8215–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waltz DA, Natkin LR, Fujita RM, et al. Plasmin and plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 promote cellular motility by regulating the interaction between the urokinase receptor and vitronectin. J Clin Invest 1997;100:58–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bousquet J, Jeffery PK, Busse WW, et al. Asthma. From bronchoconstriction to airways inflammation and remodeling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:1720–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holgate ST. Epithelium dysfunction in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120:1233–44; quiz 45–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davies DE. The role of the epithelium in airway remodeling in asthma. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2009;6:678–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heguy A, Harvey BG, Leopold PL, et al. Responses of the human airway epithelium transcriptome to in vivo injury. Physiol Genomics 2007;29:139–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuramoto E, Nishiuma T, Kobayashi K, et al. Inhalation of urokinase-type plasminogen activator reduces airway remodeling in a murine asthma model. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2009;296:L337–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Danahay H, Atherton H, Jones G, et al. Interleukin-13 induces a hypersecretory ion transport phenotype in human bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2002;282:L226–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wadsworth SJ, Nijmeh HS, Hall IP. Glucocorticoids increase repair potential in a novel in vitro human airway epithelial wounding model. J Clin Immunol 2006;26:376–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Byrne PM. Global guidelines for asthma management: summary of the current status and future challenges. Pol Arch Med Wewn 2010;120:511–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobayashi H, Ohi H, Sugimura M, et al. Inhibition of in vitro ovarian cancer cell invasion by modulation of urokinase-type plasminogen activator and cathepsin B. Cancer Res 1992;52:3610–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghosh S, Johnson JJ, Sen R, et al. Functional relevance of urinary-type plasminogen activator receptor-alpha3beta1 integrin association in proteinase regulatory pathways. J Biol Chem 2006;281:13021–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Legrand C, Polette M, Tournier JM, et al. uPA/plasmin system-mediated MMP-9 activation is implicated in bronchial epithelial cell migration. Exp Cell Res 2001;264:326–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiao W, Hsu YP, Ishizaka A, et al. Sputum cathelicidin, urokinase plasminogen activation system components, and cytokines discriminate cystic fibrosis, COPD, and asthma inflammation. Chest 2005;128:2316–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chu EK, Cheng J, Foley JS, et al. Induction of the plasminogen activator system by mechanical stimulation of human bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2006;35:628–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gray TE, Guzman K, Davis CW, et al. Mucociliary differentiation of serially passaged normal human tracheobronchial epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1996;14:104–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stevens PT, Kicic A, Sutanto EN, et al. Dysregulated repair in asthmatic paediatric airway epithelial cells: the role of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. Clin Exp Allergy 2008;38:1901–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazzieri R, Masiero L, Zanetta L, et al. Control of type IV collagenase activity by components of the urokinase-plasmin system: a regulatory mechanism with cell-bound reactants. EMBO J 1997;16:2319–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baramova EN, Bajou K, Remacle A, et al. Involvement of PA/plasmin system in the processing of pro-MMP-9 and in the second step of pro-MMP-2 activation. FEBS Lett 1997;405:157–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen P, Parks WC. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in epithelial migration. J Cell Biochem 2009;108:1233–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buisson AC, Zahm JM, Polette M, et al. Gelatinase B is involved in the in vitro wound repair of human respiratory epithelium. J Cell Physiol 1996;166:413–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jo M, Thomas KS, O'Donnell DM, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor-dependent and -independent cell-signaling pathways originating from the urokinase receptor. J Biol Chem 2003;278:1642–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gondi CS, Kandhukuri N, Dinh DH, et al. Down-regulation of uPAR and uPA activates caspase-mediated apoptosis and inhibits the PI3K/AKT pathway. Int J Oncol 2007;31:19–27 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dieckgraefe BK, Weems DM, Santoro SA, et al. ERK and p38 MAP kinase pathways are mediators of intestinal epithelial wound-induced signal transduction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1997;233:389–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma GD, He J, Bazan HE. p38 and ERK1/2 coordinate cellular migration and proliferation in epithelial wound healing: evidence of cross-talk activation between MAP kinase cascades. J Biol Chem 2003;278:21989–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shetty S, Padijnayayveetil J, Tucker T, et al. The fibrinolytic system and the regulation of lung epithelial cell proteolysis, signaling, and cellular viability. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2008;295:L967–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kicic A, Hallstrand TS, Sutanto EN, et al. Decreased fibronectin production significantly contributes to dysregulated repair of asthmatic epithelium. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;181:889–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mizukami IF, Todd RF., 3rd A soluble form of the urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) can bind to hematopoietic cells. J Leukoc Biol 1998;64:203–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.