Abstract

An exploratory study was conducted to answer the following questions: What are older adults’ perceptions of social media? What educational strategies can facilitate their learning of social media? A thematic map was developed to illustrate changing perceptions from the initial unanimous, strong negative to the more positive but cautious and to the eventual willingness to actually contribute content. Privacy was the primary concern and key perceptual barrier to adoption. Effective educational strategies were developed to overcome privacy concerns, including: 1) introducing the concepts before introducing the functions; 2) responding to privacy concerns; and 3) making social media personally relevant.

1. INTRODUCTION

Older adults continue to adopt older information and communication technologies like email (S. Jones & Fox, 2009), however their adoption of Web 2.0 applications lags behind younger age groups (Lenhart & Fox, 2009; Zajicek, 2007). For Internet users over the age of 65, only 7% of them maintain a profile on a social networking site. In sharp contrast, 75% of younger adults age 18–24 maintaining a profile (Lenhart, 2009).

Following the burst of the “dot-com bubble” in 2001, Web 2.0 and related concepts (e.g., social media, social networking, social computing) marked a turning point for Web services (O’Reilly, 2005). At the core of Web 2.0 is the focus on user-generated content. Whereas early Web applications provided limited opportunities for users to provide feedback, content, or create social contacts, Web 2.0 applications such as Facebook, blogs, and wikis depend entirely on such functionality (Cormode & Krishnamurthy, 2008). As part of Web 2.0 services, social media (i.e., Web applications promoting relationship development or “social networking” between users) provide a wide range of new resources and opportunities such as online relationships between users, links among different Web applications, and feedback from community members from the physical world (Agichtein, Castillo, Donato, Gionis, & Mishne, 2008).

With social media becoming an integral part of the lives of millions, little is known about the intersection of social media and the older population. How do older adults perceive social media? How might their perception of social media affect their learning of the technology? Motivated by these important and timely research questions, and in lack of existing evidence, we conducted an exploratory study examining older adults’ perception of social media and educational strategies for effective learning of social media applications by older adults.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

Earlier research on older adults’ perceptions of and attitudes toward computer technology reported mixed results. Some found that older adults were less positive about computers than their younger counterparts, while others found no difference in attitudes between older and younger age groups; despite these mixed reports in earlier research, a notable trend is that, increasingly, older adults are becoming more positive about computer technology (see Xie, 2003, for a review).

A number of studies have explored the social relationship development aspect of older adults’ use of Web applications (though the applications examined in these studies were not the typical types of social media applications as currently understood). It is argued that online communication can be an alternative to conventional communication channels in providing low-cost, easy to access self-help service for older adults (McCormack, 2010). Asynchronous communication in online communities facilitates older adults to learn at their own pace (Thomas, 2007). Active participation in online forums enhances older adults’ learning experience (Nahm, Resnick, DeGrezia, & Brotemarkle, 2009; Xie, 2007b, 2008a, 2008b, 2010), and can help them increase personal control over their lives (McMellon & Schiffman, 2002; Xie, 2005, 2006, 2007a).

To date only a handful of studies have examined the intersection between older adults and social media. One study (Pfeil, Arjan, & Zaphiris, 2009) finds that 1) older users of MySpace tend to have fewer friends on MySpace, however their friends tend to be from a more diverse range of age groups; in comparison, teenage users have more friends and their friends tend to be their age peers; 2) older users do not make full use of the multimedia functions (e.g., music, video, comments) on their profile page while teenagers do; and 3) compared with teenagers, older users tend to present and describe themselves more formally in their profiles (Pfeil et al., 2009). A case study (Harley & Fitzpatrick, 2009) of a 70-year-old video blogger on YouTube suggests that video blogging can be a useful tool for older adults to share life stories and strengthen intergenerational communications. The study suggests that when designing social media, it is important to address the “social, cultural and spiritual significance” to older users so that the technology can be made “relevant and meaningful” to their lives (p. 22).

Note that these social media studies focus on the use of social media sites by older adults who have already adopted the technology. The majority of older adults have not moved into the Web 2.0 age (Lenhart & Fox, 2009). There is ample evidence that older adults’ perceptions of computer technology affect their willingness to learn about and, subsequently, use the technology (Xie, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2010; Xie & Jaeger, 2008). To develop a more complete view of the dynamics between older adults and social media, it is necessary to examine non-users’ perceptions of social media including how their perceptions may have affected their learning of the technology, and then, to develop educational strategies that can overcome these barriers and facilitate their learning. This study begins to address these gaps in the literature.

3. RESEARCH QUESTIONS

We asked two primary research questions in this study:

What are older adults’ perceptions of social media? And

What educational strategies can facilitate older adults’ learning of social media?

4. METHODS

Weekly semi-structured, open-ended discussions were conducted in seven consecutive weeks to fully elicit participants’ feedback. This method enabled older adults to speak for themselves and revealed valuable information that is often difficult to capture by using pre-determined, fixed-response quantitative methods (R. A. Jones, Morrow, Morris, Rites, & Wekstein, 1992; Kaplan, 2005; Xie, 2009). The continuous, weekly discussions with the same group of participants over a prolonged period of time provides invaluable opportunities to examine the evolution and dynamics of these older adults’ perception of and learning experience with social media. This study is unique in this regard. All sessions took place in an urban public library that provides free computer and Internet access for the public. This public library was chosen as the research site for this study for two main reasons: first, this library serves a large portion of ethnic minorities (mainly African Americans), thus ensuring the impact of the study on these minority groups; second, this library is easily accessible by car and by public transportation (metro and bus) and is nearby to the university, ensuring convenient access to the site by the research participants as well as the researchers.

4.1 Participants

A total of 10 older adults between 61–83 years of age (M = 71.4, SD = 8.28) participated in multiple sessions of this study. On average, each session was attended by 6.7 participants (range: 4–8 participants). All participants were African Americans. Seven of them were women. Seven had at least some college education. Three participants had less than one year of Internet experience; three had between 1–3 years; the rest had more than 5 years of Internet experience. Participants were all former members of the Electronic Health Information for Life-Long Learners (eHILLL) research project and current members of the eHILLL-Older Adult Team (OAT) research project that aims to facilitate older adults’ learning and use of electronic resources for reliable health information (for more information about the eHILLL research project, see Xie & Bugg, 2009).

4.2 Materials

Each session we provided materials – developed by our own research team or from publicly available Web sources – to introduce the concepts and functions of social media and stimulate the discussion. These materials are discussed in context in the “Results” section below.

4.3 Procedure

The weekly sessions took place at the Hyattsville public library, which is a branch library of the Prince George’s County Memorial Library System in Maryland, over the course of seven consecutive weeks during April-May of 2010. Each session lasted for two hours. The activities for each session varied based on participants’ feedback from the previous session (more detailed descriptions of the activities are provided in context in “Results”). During each session, researchers took detailed notes on participants’ remarks and behaviors. To ensure full solicitation of participants’ feedback, researchers generally played a relatively passive role: instead of trying to push any particular social media site or any feature of a site to the participants, we focused on introducing the concepts and the functions. We encouraged participants to ask questions and share their thoughts and reactions – deliberately pausing at multiple points to elicit feedback. We also repeatedly explained to participants that the activities for our future sessions would depend on their feedback.

4.4 Data Analysis

Due to the scarcity of prior research, we decided to conduct data analysis by using the techniques of inductive thematic analysis, “a process of coding the data without trying to fit it into a preexisting coding frame, or the researcher’s analytic preconceptions” (Braun & Clarke, 2006, p. 83). Different from the grounded theory approach that focuses on theory development (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1998), the inductive thematic analysis technique aims to identify salient themes, which seemed more appropriate for this study in lack of prior evidence. Following the six phases of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), we first carefully reviewed the data, then generated initial codes and assigned to interesting features identified in the data. Next, we sought salient themes by collating the initial codes into one or multiple potential themes. We then reviewed these potential themes carefully to ensure that they were well supported by the data and developed the thematic map that fits well with the data. Finally, we defined, named, and refined each theme, before we wrote up the report. Meanwhile, a thorough review of the literature was conducted to help situate the data-driven themes in existing literature (Cutcliffe, 2000).

5. RESULTS

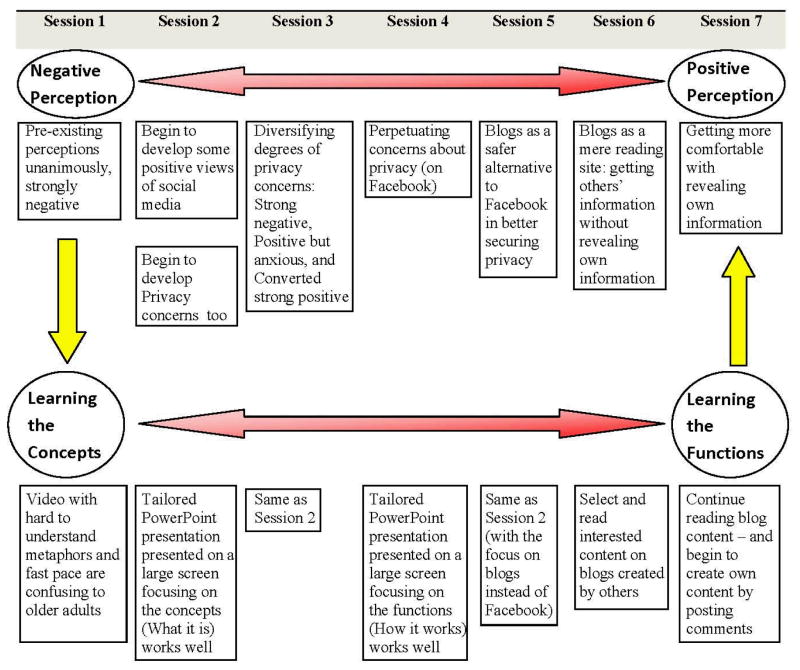

Through inductive thematic analysis, we developed a thematic map explaining the evolution of the themes and their relationships (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Thematic Map.

Below we first briefly report the activities of each session, and then report the key themes identified from each session.

5.1 Session 1: Initial introduction of the social media concepts

In this session, we examined the participants’ initial perceptions of social media. First, we led a group discussion, asking relevant, open-ended questions. Next, participants watched a brief online video introducing social media (http://commoncraft.com/social-media-pack). Participants viewed the video on individual computers using headsets, and controlled the video’s pace. We concluded with another group discussion, eliciting participants’ views with open-ended questions.

5.1.1 Pre-existing perceptions of social media

As expected, no participant possessed prior experience with social media. However, every participant knew about social media from the mass media (e.g., Mr. J said he saw blogs and Twitter on SportsNet) or younger acquaintances (e.g., Ms. M heard of Facebook from a friend’s daughter). Despite a lack of direct experience, these older adults expressed unanimously negative opinions towards social media. For instance, Ms. L and Ms. C used the term “cyber-bullying” to describe teenage Facebook users bullying classmates. Mr. J described social networking as “a community for gossip.” Last, Mr. J and Ms. C felt that social media fostered controversial political opinions.

Despite this negativity, all participants desired to learn about, but not use, social media. A primary source of interest was the use of social media by family/friends. For example, Mr. J, who heard about social media from his niece, indicated that he didn’t want to “get involved [in social media]” but still “want to know what it is” and “know enough about what’s going on.” This demonstrates an initial level of curiosity in social media existed.

5.1.2 Problems with the Video

Participants found the video confusing because of a metaphor equating social media with ice cream. We spent significant time explaining the metaphor. Also, the narrator spoke quickly and without subtitles, making the video difficult for participants to follow. Participants’ feedback reflected the video’s ineffectiveness at introducing social media concepts. As a result, we decided to develop our own materials and re-introduce the same concepts.

5.2 Session 2: Re-introduction of the social media concepts

For this session we developed a PowerPoint presentation re-introducing social media concepts. We displayed the presentation on a computer projector. The presentation explained social media at the conceptual level (e.g., defining what the words “social” and “media” mean), and prompted participants to consider the concepts underlying social media.

5.2.1 Why social media – “Why wouldn’t I just send an email?”

At this point, participants remained unclear about social media. Their initial questions focused on the situational applicability of different types of social media, suggesting an increasingly sophisticated understanding. For instance, after hearing an introduction of Facebook, Ms. M asked: “Why wouldn’t I just send an email?” Ms. V said she possessed similar questions. Later, Ms. M inquired about the differences between blogs and Facebook, stating she “was looking for distinctions.”

5.2.2 Why social media – “But most of my friends don’t have computers at home!”

Social media can be particularly attractive when our social contacts are online. Yet, many older adults lack online social contacts. For instance, Ms. M focused on contextualizing social media in her life. She expressed interest in “all the things out there” but “out of my friends, only a few have computers.” This reduced her enthusiasm for going online. She explained that of her social circle, only a friend’s daughter uses Facebook.

In the previous session participants expressed an interest in soap operas. Thus, we decided to show soap opera blogs during this session. After seeing a soap opera blog, participants became intrigued, asking “who set up this blog? Some fans?” and “Can I go there to look for information if I miss one episode?” Making social media relevant to their interests increased engagement.

5.2.3 Privacy, privacy

The primary concern of participants in this session dealt with privacy. Ms. M asked how she could maintain anonymity when writing a blog. While viewing the soap opera blog, she asked whether companies could access her email if she clicked on ads. Ms. M expressed privacy concerns after stating blogs would be useful for informing family about a sick child. She asked about public access to personal information on Facebook: “Can everyone on Facebook see my message?”

5.2.4 Interest in learning more about social media

Participants found the social media overview helpful but felt hands-on practice was necessary. Ms. M stated “the overview is helpful, but when I am trying to [actually use social media]” she would need instruction. This suggests the participants developed an interest in actually using social media.

As a result of such statements, along with our general observations, we felt that the PowerPoint presentation was better than the video at explaining social media. We decided to continue developing custom tutorials rather than use Internet-based tutorials not focused on older learners.

5.3 Session 3: Re-re-introduction of the social media concepts

In this session we replayed the PowerPoint presentation, because we wanted to progress slowly, ensuring each participant grasped the basic concepts of social media. Further, four participants missed the previous session. This proved wise, allowing us to gain a better understanding of participants’ views. Overall, participants’ views on social media divided into the following categories: Strong negative (Ms. L); Positive but cautious (e.g., Ms. C, Mr. J, and Ms. V); and Converted strong positive (Ms. M).

5.3.1 Privacy, privacy – and privacy!

Although the presentation contained the same content, the discussion differed significantly in tone and subject matter. The main reason was Ms. L, who missed the previous session, led much of this discussion. Ms. L took issue with the privacy implications of social media. Her concern focused primarily on companies selling her private information to marketers. She complained that she often receives catalogs because marketers access her personal information. She does not enjoy interruptions from marketers and stated “after working as a teacher for 48 years [I] want peace and quiet.”

While explaining Facebook’s privacy controls, Ms. L expressed strong distrust. She asked, “Will [Facecbook] make money by selling names?” She explained that “catalogs come to me with my name… they sell the list to make money.” By using social media, she reasoned, these problems would increase. Ms. L also expressed negative feelings about YouTube, a video sharing website. She described the site as “annoying” and that it contains “stupid stuff” dealing with the “dark side of human nature”. “I subscribe to the real newspaper,” she said, demonstrating an unquestionable preference for traditional media.

Other participants asked about privacy in a more personal, non-corporate context. Ms. C asked whether you could restrict content on Facebook so only certain “friends” could view your information. She expressed concern about whether a Facebook profile was publicly available: “Does everybody see a Facebook profile or the privacy setting in the computer?” Similarly, Ms. A asked how long personal content remains on Facebook. Last, Ms. M asked whether someone can locate your Facebook profile through Google. Ms. M told us that her friend “Google searched my name and my name showed up. Is that going to happen on Facebook?” This question raised the interest of Ms. C, who asked “please repeat the word: that you go to Google and eventually go to Facebook?” At the end of the session, Ms. A, who hadn’t shown a strong preference for Facebook during the session, told us “I see good things.”

Ms. M offered sharp rejoinders to Ms. L’s criticism of social media. This proved surprising, because Ms. M expressed negative views about Facebook in prior sessions. Ms. M explained the privacy issue as “something our generation worries about.” She believed that if someone “wants to find information about you, they can do it,” regardless of social media. Ms. M’s attitude towards Facebook’s privacy policies remained negative despite a newly acquired strong positive attitude of social media. She agreed that “Facebook gave information to third party without people’s approval”; but that social media could be used to communicate with distant acquaintances.

Ms. M now openly advocated for adoption, stating: “I am open to it [Facebook] now. I am going to join!” At the end of the session, she discussed joining Facebook. Another factor was at play: Ms. M received an invitation join Facebook. Her friend’s daughter set up a Facebook account for her mother, and then sent Facebook invitations to her mother’s friends. Ms. M explained: “I want to [sign up for Facebook so I can] reply to her invitation, because she’s a friend.”

From this discussion we developed a sense that we needed to better address privacy in our presentations. Also, Facebook’s privacy policy became a prominent news story. This story focused on Facebook’s “instant personalization” policy, whereby Facebook shares personal information with Websites like Yelp and Pandora. As a result, we decided future sessions should contain clear, explicit information about privacy issues surrounding each form of social media.

At this point, we felt that participants would not be overwhelmed by using a social media site. Through using an actual site, the participants might better articulate questions and concerns about social media and reduce anxiety. Thus, we decided to transition from conceptual explanations to demonstrations on how specific social media sites function.

5.4 Session 4: Moving beyond the concepts

This session introduced Facebook’s functions by using a Facebook account developed for the project. These functions included: how to establish a formal social connection with another Facebook user; how to view the photograph album on a Facebook friend’s Facebook page; how to post a public versus private message; and how to adjust the privacy settings. These functions were demonstrated step-by-step on a computer projector.

5.4.1 Privacy, privacy, and privacy – and still about privacy!

During this session, participants’ concerns still focused on privacy, particularly for photographs. For example, Ms. V asked if someone could take your picture in public, then upload it to Facebook without your permission. Participants also expressed interest in posting comments on Facebook, but with reservations: Ms. M asked about deleting posts from a friend’s profile. She asked: “[if] you leave messages on the wall, can you delete whatever you want to?”

Ms. L continued to offer opinions on privacy and direct marketing. She commented: “Those who started Facebook can check each other about what we have done, what we have bought, what we have read, and sell the information to other companies, which was discussed about on television this Thursday.”

At one point, Ms. L noticed personalized advertising on the project’s Facebook page. Ms. L. used this ad to explain how Facebook used personal information for profit. Ms. L’s gained her peers’ attention. Another participant, Ms. M asked Ms. L: “So, from what you read, they have access to your information?” Ms. L reassured Ms. M she read about this in the paper: “All those millionaires [founders of Facebook and alike] travel all over the world to glean information about marketing, to monetize – everybody can read that news.

Based on what we learned in this session, we decided to increase our focus on privacy and Facebook’s commercialization of private information. However, we also began to seriously consider social media applications that did not raise such privacy issues.

5.4.2 The last straw: the May 5, 2010 Facebook incident

On May 5th, two days prior to our next session, Facebook experienced a glitch where private chats became publicly available. This story received significant coverage on major television stations and the Internet. This was the last straw: we decided to switch focus from Facebook to blogs.

5.5 Session 5: Moving from Facebook to blogs

We started this session by asking our participants if they heard about the May 5th Facebook incident. Several participants expressed curiosity about the news. We explained the event in detail, and guided participants to a blog site with a video documenting the story. We explained that this blog site, not a traditional news outlet, broke the story. This provided a smooth transition to the topic of blogs.

5.5.1 Blogs as a safe alternative to Facebook

Following the introduction of blogs, we asked the participants how they felt about blogs. The responses ranged from enthusiastic to relative indifference. We explained that blogs are safer than Facebook because you can hide personal information by using a fake email address. Ms. M raised her voice, with apparent surprise: “You can give fake email like that, something you make up?” Ms. R responded that providing a fake email was like “you met somebody and you don’t want to reply, but give fake information so that you look like [being] polite.”

Ms. M found blogs a useful source of information. She explained that she did not see herself contributing content to a blog, but would enjoy knowing how to create a blog. Also, she considered blogs useful for sharing information. She declared, “You can find out a lot of information. You just share it if you like it, with people your age.” After noticing advertisements on the blog, she stated “ads may be good too, because [they] maybe [have] something you are looking for.” Ms. M observed job advertisements on the blog and indicated they might be a good source of job leads. “I saw jobs up there,” she said, “it gives you access to more jobs than [the] newspaper.” Ms. M found blogs safer than Facebook. Conversely, Mr. J, stated that “it’s all alphabet soup to me, I have no comments” expressing an indifference to blogs.

Realizing our participants possessed significant privacy concerns, we stressed that one advantage of blogs over Facebook is that readers can read content without contributing personal information. Also, we asked the participants what topics interested them. Ms. C stated that she wanted to read a blog on the economy. We used Google to search for blogs on the economy, demonstrating the large number of results.

5.6 Session 6: Blogs as mere reading sites

For this session we continued helping participants familiarize themselves with blogs. The activities for this session were similar to prior sessions: we first asked each participant about topics of interest, and then searched Google for relevant blogs. Next, we directed participants their choice of blog. One difference with this session is that we did not use an overhead projector. Instead, participants read blogs using their individual computers. Participants found a variety of topics, including travel, sports, and soap operas.

At the end of this session, we felt it was time to move beyond passively reading blogs. However, based on our understanding of participant privacy concerns, we felt it too early to ask participants to create blogs. As a result, we decided in the next session we would ask participants to contribute content to a blog through posting comments. This strategy could minimize the exposure of personal information but allow the participants to actively contribute content. Also, based on what we learned, we felt participants would be more engaged and comfortable using a blog with familiar content. Thus, we created a project blog site. By using a social media site that we created, we could control privacy to the fullest extent possible. Further, creating the blog permitted us to fully customize content.

5.7 Session 7: Getting more personal and interactive – the project blog site

First, we directed participants to the project blog site: [omitted for double-blind review]. This blog contains posts explaining the purposes, history, and development of the project, along with project photographs. We highlighted links participants could click to read about blog entries, and then asked participants to explore the site at their leisure.

5.7.1 Getting more personal by showing project photographs

The May 19th blog post contains a picture taken at a previous session, and shows nine participants sitting at their computers. When she saw the post, Ms. A exclaimed, “it is a big day to learn about blogs”. Participants enjoyed the picture, and spent significant time discussing and identifying themselves in the photo. The picture was taken from some distance, to demonstrate how the project is run at the library. This makes it difficult to recognize individuals. However, participants expressed great joy in collectively identifying people in the picture, laughing every time they recognized someone. This affirmed our prediction that participants would be more engaged with personally relevant content.

Showing the picture also acclimated the participants to revealing personal information online. Despite privacy concerns, participants did not mind seeing their photograph online. When we originally took the picture, we obtained participant consent. During this session, we specifically asked whether anyone minded having the picture posted online. We emphasized that the picture was publicly available, and we were prepared to remove the picture based on participant request. No participant wanted the picture removed.

5.7.2 Getting more interactive through replying to a party invitation

Our next goal was increasing participant interactivity with the blog through the comments function. Unlike Facebook, users can comment on blogs without revealing personal information. We instructed the participants to read a blog entry about a luncheon scheduled in mid-June honoring the librarians helping with the project. Next, we asked participants to indicate whether they might be able to attend the luncheon by using the blog’s “Post a Comment” function.

Participants were enthusiastic to reply but did not know how to leave comments. Leaving a comment requires signing in with using a Gmail username. We assisted participants experiencing difficulty signing in. At the session’s end, each participant successfully replied to the invitation. This marked the first time these older adults contributed content to a social media site.

We encouraged participants to post comments on other blog entries of this site to provide feedback about the project. Participants responded well: they began using the “Post a Comment” feature to express their opinion of the project. For instance, Mr. E asked us to teach wikis and Facebook. Ms. C expressed interest in the formalities of sending an email.

In the future, we hope to use the project blog site to increase the collaborative nature of the project. Participants can freely submit suggestions, questions, and other content (e.g., pictures) to the blog. Further, we will continue to use a slow, iterative approach to introducing social media. Our approach involves explaining the concepts behind a social media tool, demonstrating how to use the tool, and then encouraging the participants to try the tool in a controlled environment. This approach ensures safety and privacy and avoids confusion.

6. DISCUSSION

A few years ago, it was already declared that social networking sites had “matured” to the “age-neutral” stage where individuals, young or old, used social networking sites in their daily lives (Stroud, 2008). More recently, some gerontologists have also suggested that social networking sites are “not just for kids anymore” (Creamer, Stripling, & Heesacker, 2009).

Against these (over-)optimistic views, at the onset of this study our participants demonstrated great resistance to social networking sites. Their initial perceptions of social media were unanimous and overwhelmingly negative. They associated social media sites with disruptive teenage behavior such as cyber-bullying and gossip. This finding is in line with that of another study (Lehtinen, Näsänen, & Sarvas, 2009) which found that social networking sites were perceived by older adults as “places of socially unacceptable behavior” (p. 45). These similar findings support the generalizability of these types of perceptions across diverse populations of older adults.

Over the course of seven consecutive weeks, participants’ perceptions of social media transitioned from a unanimous, overwhelmingly negative view to a more positive, engaged perspective. At first glance, this transition seemed to be the opposite of what was found in an interview study of younger people’s (aged between 13–24) perceptions of Wikipedia (Luyt, Zainal, Mayo, & Yun, 2008). In that study, younger people reported an initial attraction to Wikipedia, but over time they limited use to specific tasks as they became aware of the limitations of the technology (i.e., the accuracy of information on Wikipedia) (Luyt et al., 2008). Note though, in both studies, each age group started with simplistic, uninformed preconceptions. After improving their knowledge of social media, each group’s conceptions became more realistic, realizing the technology’s strengths and limitations. These findings suggest that groups with a one-sided view of social media caused by a lack of full understanding of the technology may change their perceptions and behavior as their knowledge increases.

Privacy was the primary concern of the older adults. Throughout the study, participants consistently expressed strong concerns about protecting personal information on social media sites. Privacy concerns, along with confusion about operating social media privacy settings, are not unique to older adults. Previous research demonstrates that technologically savvy populations such as teens and undergraduates have concerns about disclosing private information on social networking sites (Lipford, Besmer, & Watson, 2008; Livingstone, 2008; Rosenblum, 2007). Research also shows that these users generally do not adjust available privacy controls (Gross, Acquisti, & Heinz, 2005). Follow-up work (Lipford et al., 2008) shows these users found the privacy settings confusing and difficult to use, explaining the failure to adjust them.

Differences do exist between age groups regarding privacy concerns. Some evidence suggests the traditional distinction between public and private life becomes blurred for younger people using social networking sites like Facebook (West, Lewis, & Currie, 2009). An interesting question is, as younger people age, would they continue to blur the public/private dichotomy or, rather, would they develop views similar to those now held by the current generation of older adults? Conversely, will the present generation of older adults similarly blur this distinction as they increasingly incorporate social media into their life?

Participants’ perception of social media sites as inadequately protecting privacy was a key perceptual barrier to adoption. Our customized educational strategies, which evolved as our understanding of participants’ perceptions improved, helped the older adults overcome some of their privacy concerns. As a result, the older adults willingly contributed their own content to our blog site. Our customized educational strategies included:

First, we explained concepts before introducing Website functions. During the first three sessions, we focused on introducing the concepts of social media to ensure the older adults developed an understanding of social media before introducing any functions. This strategy appeared to help participants develop a comprehensive view of social media, decreasing negative perceptions while increasing interest and enthusiasm.

Second, we responded to participants’ concerns by thoroughly discussing privacy concerns, along with altering session plans to accommodate these concerns. This is evident in our transition away from Facebook as a result of Facebook’s problematic privacy controls. This is also evident in our initial presentation of blogs as simplistic sites where users can read others’ information without sacrificing their privacy.

Third, to help participants become more comfortable with generating content, we introduced participants to a blog relevant to their lives. Our project’s blog contains project information (presented in text and pictures) familiar to the participants. Using a personally relevant blog helped the older adults overcome privacy concerns to the point where they felt comfortable contributing content (e.g., pictures, blog posts) to the blog. Similarly, another study (Karahasanovic, 2009) found that older adults rarely contribute content to social networking sites. However, when content generation in the online world is tightly connected to their life in the offline world (e.g., generating content reflecting their social heritage, identify, and relationships), older adults can be inspired to generate content including photographs, videos, and blog entries and posts. These studies suggest that, while older adults typically possess privacy concerns with social media, these concerns can be overcome through proper educational strategies that promote personal relevance.

Fourth, we used individual computers and an overhead projector during our sessions. We initially employed the computer projector because of difficulties in pacing participants with different levels of computer literacy. Further, when explaining social media at the conceptual level, little need existed for participants to use their own computers. However, when introducing the functions of social media, having the participants use individual computers proved essential. Without using individual computers, the participants would not likely have felt as engaged or comfortable generating their own content.

Participants’ engagement with social media is also evident in their growing interest in trying to understand the distinctions between social media sites and applications like email. Similarly, the participants questioned how social media sites would be useful in different situations. For example, one participant mentioned that a blog would be useful to communicate information about a sick family member. This suggests that the older adults already consider circumstances where the technology could improve their lives. As the older adults become more familiar with the technology, they will likely integrate it into their daily life in significant and profound ways. That will be the point where their use of social media reaches maturation.

6.1 Limitations

The current study has some limitations. Since this was an exploratory study, the results were derived from a small convenience sample. The participants were all African American and predominantly female who had some computer experience. Additional research should address other groups (e.g., males, non-African Americans, older adults with less computer experience) to determine whether the results could be generalized.

7. CONCLUSION

In lack of prior research, in this study we took a qualitative, bottom-up approach to fully explore older adults’ perceptions of social media, which changed from the initial unanimous, strong negative to the more positive but cautious and to the eventual willingness to actually contribute content. Privacy was the primary concern and perceptual barrier to adoption. The educational strategies developed in the process were effective in overcoming some privacy concerns. These educational strategies included: 1) introducing the concepts before introducing the functions; 2) responding to participants’ concerns; and 3) making social media personally relevant. These findings advance scientific knowledge about the interaction between older adults and new technology like social media applications. They also shed light on the development of educational interventions to facilitate the older generation’s adoption of new technology.

Acknowledgments

We thank the older adults, librarians, and graduate students who helped to make this study possible. The Electronic Health Information for Life-Long Learners (eHILLL) research project was funded with Federal funds from the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. NO1-LM-6-3502 with the University of Maryland Baltimore. The eHILLL-Older Adult Team (OAT) research project is funded by a 3-year Faculty Early Career Development Award to Bo Xie from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS).

References

- Agichtein E, Castillo C, Donato D, Gionis A, Mishne G. Finding high-quality content in social media. Proceedings of the International Conference on Web Search and Web Data Mining; 2008; 2008. pp. 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Cormode G, Krishnamurthy B. Key differences between web 1.0 and web 2.0. First Monday. 2008;13(6):2. [Google Scholar]

- Creamer A, Stripling AM, Heesacker M. Social networking sites, not just for kids anymore: How to recruit older adults online. Gerontologist. 2009;49:280. [Google Scholar]

- Cutcliffe JR. Methodological issues in grounded theory. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2000;31:1476–1484. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Gross R, Acquisti A, Heinz HJ. Information revelation and privacy in online social networks. In WPES '05 Proceedings of the 2005 ACM workshop on Privacy in the electronic society; 2005; New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2005. pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Harley D, Fitzpatrick G. YouTube and intergenerational communication: The case of Geriatric1927. Universal Access in the Information Society. 2009;8(1):5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Jones RA, Morrow GD, Morris BR, Rites JB, Wekstein DR. Self-perceived information needs and concerns of elderly persons. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1992;74:227–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Fox S. Generations Online in 2009. Washington DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2009. Retrieved June 13, 2010 from http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2009/Generations-Online-in-2009.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan B. Qualitative evaluation in consumer health informatics. In: Lewis D, Eysenbach G, Kukafka R, Stavri PZ, Jimison HB, editors. Consumer health informatics: informing consumers and improving health care. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Karahasanovic A, Brandtzæg PB, Heim J, Lüders M, Vermeir L, Pierson J, et al. Co-creation and user-generated content-elderly people's user requirements. Computers in Human Behavior. 2009;25(3):655–678. [Google Scholar]

- Lehtinen VJ, Näsänen J, Sarvas R. A little silly and empty-headed: Older adults' understandings of social networking sites. Proceedings of the 2009 British Computer Society Conference on Human-Computer Interaction; 2009. pp. 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A. Adults and social network Websites. Vol. 2009. Washington DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2009. Retrieved June 13, 2010, from http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2009/Adults-and-Social-Network-Websites.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A, Fox S. Twitter and status updating. Washington DC: PEW Internet & American Life Project; 2009. Retrieved June 14, 2010 from http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2009/Twitter-and-status-updating.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Lipford HR, Besmer A, Watson J. Understanding privacy settings in facebook with an audience view. Proceedings of the 1st Conference on Usability, Psychology, and Security; San Francisco, California. April 14 - 14, 2008.2008. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone S. Taking risky opportunities in youthful content creation: teenagers' use of social networking sites for intimacy, privacy and self-expression. New Media & Society. 2008;10(3):393–411. [Google Scholar]

- Luyt B, Zainal CZBC, Mayo OVP, Yun TS. Young people's perceptions and usage of Wikipedia. Information Research. 2008;13(4) paper 377. Available at http://InformationR.net/ir/313-374/paper377.html. [Google Scholar]

- McCormack A. Individuals with eating disorders and the use of online support groups as a form of social support. Cin-Computers Informatics Nursing. 2010;28(1):12–19. doi: 10.1097/NCN.0b013e3181c04b06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMellon CA, Schiffman LG. Cybersenior empowerment: How some older individuals are taking control of their lives. The Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2002;21(2):157–175. [Google Scholar]

- Nahm ES, Resnick B, DeGrezia M, Brotemarkle R. Use of discussion boards in a theory-based health Web site for older adults. Nursing Research. 2009;58(6):419–426. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181bee6c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly T. What is Web 2.0. O’Reilly Media; 2005. Retrieved June 13, 2010 from http://oreilly.com/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeil U, Arjan R, Zaphiris P. Age differences in online social networking-A study of user profiles and the social capital divide among teenagers and older users in MySpace. Computers in Human Behavior. 2009;25(3):643–654. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum D. What anyone can know: the privacy risks of social networking sites. IEEE Security and Privacy. 2007;5(3):40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Stroud D. Social networking: An age-neutral commodity—Social networking becomes a mature web application. Journal of Direct, Data and Digital Marketing Practice. 2008;9(3):278–292. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CM. Bulletin boards - A teaching strategy for older audiences. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2007;33(3):45–52. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20070301-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West A, Lewis J, Currie P. Students' facebook ‘friends’: Public and private spheres. Journal of Youth Studies. 2009;12(6):615–627. [Google Scholar]

- Xie B. Older adults, computers, and the Internet: Future directions. Gerontechnology. 2003;2(4):289–305. [Google Scholar]

- Xie B. Getting older adults online: The experiences of SeniorNet (USA) and OldKids (China) In: Jaeger B, editor. Young Technologies in Old Hands - An International View on Senior Citizens' Utilization of ICT. Copenhagen, Denmark: DJOF Publishing; 2005. pp. 175–204. [Google Scholar]

- Xie B. Perceptions of computer learning among older Americans and older Chinese. First Monday. 2006;11(10) URL: http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1408/1326. [Google Scholar]

- Xie B. Older Chinese, the Internet, and well-being. Care Management Journals: Journal of Long Term Home Health Care. 2007a;8(1):33–38. doi: 10.1891/152109807780494122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie B. Using the Internet for offline relationship formation. Social Science Computer Review. 2007b;25(3):396–404. [Google Scholar]

- Xie B. Multimodal computer-mediated communication and social support among older Chinese. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2008a;13(3):728–750. [Google Scholar]

- Xie B. The mutual shaping of online and offline social relationships. Information Research. 2008b;13(3) paper350. http://InformationR.net/ir/313-353/paper350.html. [Google Scholar]

- Xie B. Older adults' health information wants in the Internet age: Implications for patient-provider relationships. Journal of Health Communication. 2009;14(6):510–524. doi: 10.1080/10810730903089614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie B. Perceiving an Internet community as a “Utopia”: Beliefs, norms, and resistance among Older Chinese. In: Zaphiris P, editor. Social Computing and Virtual Communities. Taylor & Francis; 2010. pp. 243–262. [Google Scholar]

- Xie B, Bugg JM. Public library computer training for older adults to access high-quality Internet health information. Library & Information Science Research. 2009;31:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.lisr.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie B, Jaeger PT. Computer training programs for older adults at the public library. Public Libraries. 2008;47(5):42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Zajicek M. Web 2.0: hype or happiness?. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series; Oxford: Oxford Brookes University; 2007. pp. 35–39. [Google Scholar]