Abstract

Rational engineering of filamentous fungi for improved cellulase production is hampered by our incomplete knowledge of transcriptional regulatory networks. We therefore used the model filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa to search for uncharacterized transcription factors associated with cellulose deconstruction. A screen of a N. crassa transcription factor deletion collection identified two uncharacterized zinc binuclear cluster transcription factors (clr-1 and clr-2) that were required for growth and enzymatic activity on cellulose, but were not required for growth or hemicellulase activity on xylan. Transcriptional profiling with next-generation sequencing methods refined our understanding of the N. crassa transcriptional response to cellulose and demonstrated that clr-1 and clr-2 were required for the bulk of that response, including induction of all major cellulase and some major hemicellulase genes. Functional CLR-1 was necessary for expression of clr-2 and efficient cellobiose utilization. Phylogenetic analyses showed that CLR-1 and CLR-2 are conserved in the genomes of most filamentous ascomycete fungi capable of degrading cellulose. In Aspergillus nidulans, a strain carrying a deletion of the clr-2 homolog (clrB) failed to induce cellulase gene expression and lacked cellulolytic activity on Avicel. Further manipulation of this control system in industrial production strains may significantly improve yields of cellulases for cellulosic biofuel production.

Hydrolysis of cellulose to glucose is a major bottleneck in cellulosic biofuel production processes (1). In nature, fungal cellulases act within a complex repertoire of enzymes to synergistically deconstruct plant cell wall polysaccharides (1, 2) (Fig. S1) and industrial production of fungal cellulases is expected to play a major role in next-generation biofuel production (1). A combination of process engineering and random mutagenesis of fungal species has greatly improved hydrolytic enzyme production from industrial strains (3). However, rational engineering of regulatory networks will likely be necessary to further increase productivity and specificity of enzyme secretion.

Fungal cellulase gene expression and secretion are tightly controlled at the transcriptional level (4–6). The most extensive work on cellulase gene transcription in filamentous fungi has been done in Aspergillus niger and Hypocrea jecorina (Trichoderma reesei) (3, 7). Several small metabolites have been identified as soluble inducers of expression of cellulase genes in H. jecorina, including lactose (8), cellobiose (9), and sophorose (10), and xylose induces expression of some cellulase genes in A. niger (5). These inducers drive expression of overlapping but distinct assemblages of cellulase, hemicellulase, and β-glucosidase genes.

In Aspergilli and H. jecorina, expression of cellulase and hemicellulase genes requires the conserved fungal transcription factor XlnR/XYR1 (5, 7, 11). Although xlnR/xyr1 homologs are important for hemicellulase induction in Fusarium species and in Neurospora crassa, they do not play a significant role in cellulase gene expression (12–14). Other genus-specific transcriptional activators (such as ACE2 in H. jecorina) appear to have some specificity for particular inducers, but deletion strains for these transcription factors still induce significant cellulase secretion (15). These findings suggest that a complex network of transcriptional activators is required for cellulase and hemicellulase gene induction and secretion in filamentous fungi.

N. crassa colonizes freshly burned plant material (16, 17). N. crassa shows robust growth on cellulosic material, which is enabled by a diverse hydrolytic secretome (6, 18). An initial study on N. crassa’s utilization of cellulose yielded promising candidate genes that were subsequently used in engineering strategies for improved cellulosic biofuel production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (19) and contributed insights into a role for polysaccharide monooxygenases in cellulose deconstruction (20, 21).

Transcriptional studies of N. crassa identified an uncharacterized predicted transcription factor that was induced on cellulosic substrates (6). That discovery prompted a broader search for transcription factors necessary for degradation and utilization of cellulose by assessing a near-full genome deletion strain set in N. crassa (22). Using these tools, we identified two transcription factors (clr-1 and clr-2) that are required for degradation of cellulose and explored the effects of clr-1 and clr-2 deletion mutants on the transcriptional response to cellulose. Homologs of clr-1 and clr-2 are present in the genomes of a wide variety of filamentous ascomycete species capable of degrading plant cell-wall material. We show that in the distantly related fungus, Aspergillus nidulans, a homolog of clr-2 (clrB) was also required for cellulolytic activity, but a homolog of clr-1 (clrA) modulated cellulase gene expression. These data indicate that homologs of CLR-1 and CLR-2 play an important role in plant cell-wall degradation in filamentous ascomycete fungi.

Results

Essential Regulators for Cellulose Degradation in N. crassa.

To identify transcription factors required for cellulose degradation in an unbiased fashion, we screened the N. crassa transcription factor deletion set (22) for mutants with deficient growth on cellulose (Avicel) (SI Materials and Methods). This screen identified approximately two-dozen poorly characterized transcription factors with a spectrum of effects for growth and activity on Avicel. Although strains containing deletions of genes involved in plant cell-wall degradation in H. jecorina and Aspergilli were present in the collection, including homologs to xlnR (5) (NCU06971), ace1 (23) (NCU09333), and hap2 (24) (NCU03033), in N. crassa these mutants showed no significant growth defects on Avicel. However, other deletion strains for transcription factors with a known influence on cellulase production were identified, including nit-2 (NCU09068, a homolog to the nitrogen regulator areA) (25), pacC (NCU00090, pH sensing) (26), and cre-1 (NCU08807, carbon catabolite repression) (27). The strain that exhibited the most severe growth defect on Avicel, but not on either sucrose or xylan, contained a deletion of NCU07705, which was previously identified as induced under cellulolytic conditions (6) (Fig. S2). A second mutant, which contained a deletion of NCU08042, also exhibited a particularly severe growth defect on Avicel (Fig. S2). NCU07705 and NCU08042 were provisionally named clr-1 and clr-2, respectively, for cellulose degradation regulator 1 and 2.

The clr-1 and clr-2 genes encode proteins that belong to the fungal-specific zinc binuclear cluster superfamily (Fig. S2). This large and diverse family of transcriptional regulators (28) includes many previously described regulators of alternative carbon metabolism, including the S. cerevisiae transcriptional activator Gal4, and the H. jecorina cellulosic regulators XYR1 and ACE2. Members of this family typically have two conserved domains, a zinc binuclear cluster coordinating DNA binding, and a conserved middle homology domain, which is often associated with regulation of transcription factor activity (28). Both CLR-1 and CLR-2 have the canonical domain architecture for zinc binuclear cluster transcription factors, although the middle homology domain of CLR-2 is truncated (Fig. S2).

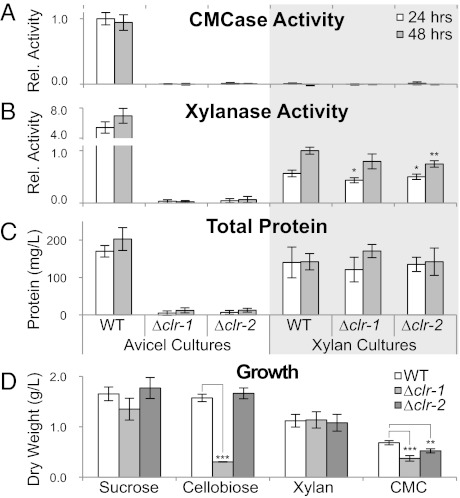

Deletion strains for clr-1 and clr-2 (Δclr-1 and Δclr-2) grown for 16 h on sucrose and then transferred to Avicel for 24–48 h showed no detectable cellulase activity when assayed for cleavage of carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) (Fig. 1). The Δclr-1 and Δclr-2 mutants secreted ∼5% of total protein compared with WT strains under cellulolytic conditions (Fig. 1 and Fig. S2) and displayed only trace levels of xylanase activity. However, when the Δclr-1 and Δclr-2 mutants were grown on sucrose for 16 h and then switched to xylan, they displayed near WT hemicellulase activity and secreted protein levels (Fig. 1) as well as similar banding patterns on SDS/PAGE gels (Fig. S2). The cellulolytic phenotype segregated with the hygromycin marker used to disrupt NCU07705 and NCU08042 and was complemented by introduction of a WT copy of NCU07705 or NCU08042 at the his-3 locus. Neither WT strains nor the clr mutants showed cellulolytic activity when exposed to hemicellulosic substrates (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Growth and activity phenotype of clr deletion strains. (A–C) Carboxymethyl cellulose hydrolysis (CMCase) activity, xylanase activity, and total protein in supernatants from WT and clr mutant cultures grown on sucrose for 16 h and subsequently transferred to Avicel or xylan. (D) Mycelia dry weights from carbon-limited cultures on soluble carbon sources (0.5% wt/vol except for CMC, which was 2%). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

The Δclr-1 and Δclr-2 mutants showed an identical phenotype when grown on sucrose (WT growth), xylan (WT growth), and cellulose (no growth). However, the Δclr-1 mutant was deficient for growth on cellobiose, which is the major hydrolytic product of cellulose degradation, and the Δclr-2 mutant grew similarly to WT (Fig. 1D). These data suggest that CLR-1 and CLR-2 may differentially regulate gene sets associated with plant cell-wall degradation, in particular genes encoding β-glucosidase enzymes, which are involved in hydrolysis of cellobiose to glucose (Fig. S1).

Induction of Cellulose Degrading Enzymes in WT N. crassa.

To better understand processes by which filamentous fungi sense and respond to cellulose in their environment, we used next generation RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) to profile genome-wide mRNA abundance in WT N. crassa when exposed to Avicel. WT cultures were grown for 16 h on sucrose and then shifted to Avicel as a sole carbon source. RNA samples were taken at 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, and 4 h following the shift, and relative transcript abundances were measured.

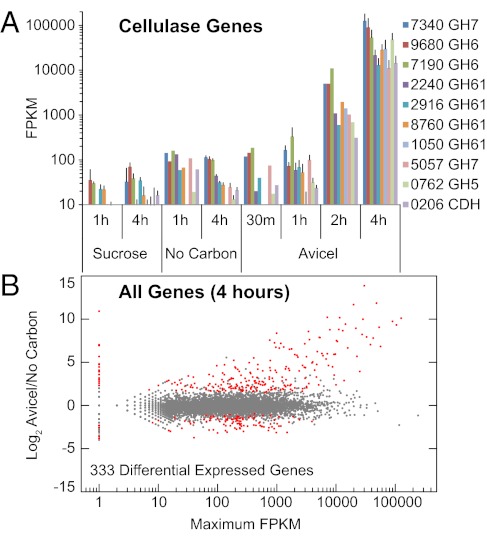

Within 30 min of transfer to Avicel, mRNA abundance for cellulase genes increased 2- to 10-fold (Fig. 2A). This level of transcription was maintained until 1 h after the shift, then cellulolytic genes were further induced several thousand-fold. Expression patterns for hemicellulase genes exhibited a similar two-stage induction (Fig. S3). A conservative differential expression analysis (see Materials and Methods) between Avicel and sucrose cultures at 4 h called nearly 40% of the genome with functional category enrichments (29), dominated by a general decrease in transcription, translation, and mitochondrial biogenesis (Fig. S4). As an alternative reference condition, we shifted cultures to minimal media with no added carbon source. The “no carbon” cultures showed the same initial increase in cellulase gene transcription as observed on Avicel, but without the later, more substantial induction (Fig. 2B). Only 333 genes were differentially expressed between Avicel and no carbon cultures at 4 h (Fig. 2B). This gene set was enriched for induction of the C-compound and carbon metabolism, extracellular metabolism, and polysaccharide-binding functional categories (Fig. S4). Given the similarity of transcriptional profiles between Avicel and no carbon conditions, especially at 1 h posttransfer, we interpret the first stage of induction as the relief of carbon catabolite repression (de-repressed phase), followed by a true induction phase in response to a cellulosic signal (inductive phase).

Fig. 2.

Transcriptional induction by cellulosic substrates in N. crassa as measured by RNA-Seq. (A) Message abundance in FPKM for 10 cellulase genes after transfer of a 16-h sucrose-grown culture to either sucrose, no carbon source, or Avicel. Error bars show ± 1 SD for conditions with triplicate measurements. Conditions without error bars are from single libraries. Genes listed by NCU number (39) and CAZy class (43). (B) Comparison of full genome-expression profiles after transfer of a sucrose-grown culture to Avicel vs. no added carbon source. Log2 ratio of Avicel/no carbon FPKM vs. maximum FPKM in either condition. Genes detectable in one condition but not the other are plotted along the y axis (nonexpressed condition set to 1 FPKM). Genes exhibiting differential expression [identified by DESEq (42) and EdgeR (44)] are plotted in red.

Of the 333 genes differentially expressed between Avicel and no carbon conditions, 212 had greater expression on Avicel than under either no carbon or sucrose conditions (Fig. S5). We refer to this gene set as a conservative “Avicel regulon.” The Avicel regulon included 17 of 21 predicted cellulase and 11 of 19 predicted hemicellulase genes (6), 22 genes encoding enzymes with predicted activity on polysaccharides, and 56 additional genes encoding proteins predicted to enter the secretory pathway (Dataset S1). Also induced were genes for 13 transporters [including two recently identified cellodextrin transporters (19)], three components of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) translocation complex, two ER disulfide isomerases, two ER chaperones (HSP70 and calreticulin), seven cytosolic enzymes with predicted activity on disaccharides, a homolog to Aspergilli and H. jecorina xlnR/xyr1 (5, 30), and both clr-1 and clr-2. Also included in the Avicel regulon were 92 proteins annotated as conserved hypothetical proteins or with no predicted function, 31 of which are predicted to enter the secretory pathway.

Transcriptional Profiles of clr Deletion Mutants.

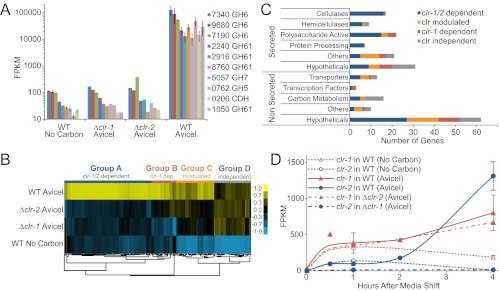

To compare expression of the Avicel regulon with WT, the Δclr-1 and Δclr-2 mutants were subjected to transcriptional profiling (Fig. 3). Four hours after transfer to Avicel media, both clr deletion strains showed a expression profile similar to WT no carbon samples (Fig. S6) and failed to induce transcription of all cellulases (Fig. 3A) and 5 of the 10 most highly expressed hemicellulase genes (Fig. S3). Hierarchical clustering of expression patterns for the 212 genes specifically induced on Avicel (Fig. 3B) revealed four major groups of genes with similar expression patterns. A summary of the Avicel regulon and dependence of major categories on clr-1 and clr-2 is presented in Fig. 3C.

Fig. 3.

The clr regulon. (A) FPKM of 10 cellulase genes in WT and clr deletion strains when exposed to Avicel for 4 h. Error bars show ± 1 SD for conditions with triplicate measurements. Conditions without error bars are from single clr mutant libraries. (B) Expression patterns for the 212 genes in the Avicel regulon in WT and the clr mutants. Group A includes 98 genes that were clr-1/2–dependent, Group B includes 28 genes that were clr-1–dependent, Group C contained 43 genes that were clr-modulated, and group D included 42 genes that were clr-independent. (C) Distribution of genes in functional categories (29) among groups identified in B. (D) Time course of expression of clr-1 and clr-2 in WT and clr mutant strains after transfer to Avicel from sucrose media.

Group A (clr-1/2–dependent) consisted of 98 genes that showed no induction in both Δclr-1 and Δclr-2 mutants. This group included 16 cellulases, 6 hemicellulases, 15 genes encoding enzymes with activity on polysaccharides, and 14 other enzymes predicted to enter the secretory pathway (Dataset S1). The group also includes three components of the ER translocation complex, two disulfide isomerases, as well as two ER chaperones (HSP70 and calreticulin). Genes within group A were the most strongly induced in the Avicel regulon.

Group B (clr-1–dependent) consisted of 28 genes (including clr-2) that were not induced above no carbon levels in the Δclr-1 mutant and had intermediate expression levels in the Δclr-2 strain. This group of genes was the least well-supported cluster and many could be included in group A. This group is dominated by 16 conserved hypothetical proteins, but also includes six enzymes with predicted function on polysaccharide and oligosaccharides (including a putative β-glucosidase), a xlnR/xyr1 homolog (NCU06971), and a major exoglucanase, NCU07190.

Group C (clr-modulated) consisted of 43 genes, the expression levels of which were modulated by clr-1 and/or clr-2, but which were at least partially induced over no carbon levels in both deletion mutants (Dataset S1). This group includes 18 secreted enzymes, including three lipases, three monoxygenases, five enzymes with predicted activity on polysaccharides or disaccharides, and four transporters, including NCU08114, a high-affinity cellodextrin transporter (19).

Group D (clr-independent) consisted of 42 genes with WT induction in both mutants. This group included four highly expressed hemicellulase genes and several genes with predicted function related to xylose or other pentose utilization (Dataset S1).

We used a selection of promoter regions of the most strongly induced cellulase genes to search for conserved motifs that could function as binding sites for CLR-1/CLR-2 or other factors in complex with them. We identified several putative motifs with a variety of established algorithms (Fig. S7). However, when considered with the genome at large, occurrence of these motifs in a promoter region for a gene had no correlation with relative expression of that gene on Avicel.

Transcriptional Regulation of clr-2 by clr-1.

When WT N. crassa was transferred to Avicel, clr-1 and clr-2 initially showed an expression level similar to no carbon controls (de-repressed phase) (Fig. 3D). However, although clr-1 was more highly expressed in the de-repressed phase, clr-2 showed significantly higher expression levels in the inductive phase. Importantly, in the Δclr-1 mutant, expression of clr-2 was abolished (Fig. 3D). Expression levels of clr-1 were unaffected in the Δclr-2 mutant. These data suggest that clr-2 is under transcriptional regulation by CLR-1 and that the relative abundance of CLR-1 under de-repressed conditions is insufficient for induction of clr-2 expression. Thus, some signaling to CLR-1 through posttranslational modification or alteration in protein interactions is likely required for its activation (see Fig. 5).

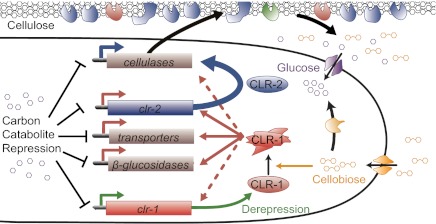

Fig. 5.

Model of cellulase induction mediated by CLR-1 and CLR-2 in N. crassa. When de-repressed, genes encoding cellulases, β-glucosidases, cellobiose transporters, and CLR-1 are expressed at low levels. CLR-1 is activated in the presence of cellobiose, promoting expression of cellodextrin transporters and β-glucosidase genes. Activated CLR-1 is necessary for increased expression levels of clr-2 and may also regulate its own expression. CLR-2 (possibly in concert with CLR-1) drives expression of the Avicel regulon, releasing more cellobiose in a positive feedback loop.

Conservation of CLR Protein Sequences and Function in Filamentous Ascomycete Fungi.

A phylogenetic analysis of CLR-1 and CLR-2 protein sequences showed broad conservation across filamentous ascomycete fungi. Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees of CLR-1 and CLR-2 homologs largely recapitulate previously published fungal trees (31) (Fig. S8). One notable exception to this congruence of species and gene trees was the CLR-1 homolog from H. jecorina. Homologs for both proteins can be found in most filamentous ascomycete species; exceptions are the animal fungal pathogens Coccidioides immitus and Coccidioides posadasii, and the closely related saprophyte Uncinocarpus reesii, which have lost their clr-1 homolog. Additionally, a clr-2 homolog was not identified for Grosmannia clavigera, which causes blue-stain disease on pines.

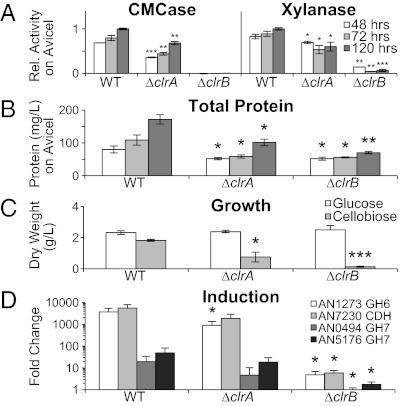

To assess whether clr-1 and clr-2 homologs function to regulate genes involved in plant cell-wall deconstruction in other filamentous ascomycete species, we created deletion strains in the distantly related fungus A. nidulans in AN5808 (clrA) and AN3369 (clrB). Similar to N. crassa Δclr-1 and Δclr-2 mutants, the A. nidulans ΔclrA and ΔclrB deletion strains were deficient for cellulase and xylanase activity, as well as total protein secretion when pregrown glucose cultures were transferred to Avicel (Fig. 4). Enzyme activity was abolished in the ΔclrB mutant, but the ΔclrA mutant showed ∼50% of WT activity (Fig. 4 A and B). Both deletion mutants were deficient for growth on cellobiose, although ΔclrB was more strongly affected (Fig. 4C). Consistent with enzyme data, the induction pattern of major cellulase genes in the ΔclrB mutant was several thousand-fold less than WT (Fig. 4D), but in the ΔclrA mutant, the average induction was two- to fourfold less. On a per-gene basis, this decrease was not statistically significant (P < 0.05) for three of four tested cellulases (P = 0.049, 0.052, 0.105, and 0.121 for AN1273, AN7230, AN0494, and AN5175, respectively), but considering all of the genes together, the null hypothesis that ΔclrA has WT levels of cellulase gene expression was not supported. From these data we conclude that clrA has a less important role in cellulase induction in A. nidulans compared with clr-1 in N. crassa. However, the function of CLR-2/ClrB as an essential activator for cellulase gene expression and activity is conserved between N. crassa and A. nidulans, two of the most widely divergent species of filamentous ascomycete fungi.

Fig. 4.

Phenotype of A. nidulans clr deletion strains. (A) Enzyme activity of culture supernatants from ΔclrA and ΔclrB mutants grown on glucose and then shifted to Avicel medium. (B) Total protein in supernatants of cultures grown on Avicel. (C) Mycelial dry weights from WT and clr mutants from cultures on glucose and cellobiose (0.5% wt/vol). (D) Induction of selected cellulase genes in WT and the clr mutants following an 8-h shift to Avicel, by quantitative RT-PCR. Statistical significance by one tailed, unequal variance t-test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

By using genomic resources for N. crassa, we identified two conserved transcription factors that are important regulators of genes encoding enzymes that are required for deconstruction of cellulose. Despite the complete loss of induced cellulase gene expression and cellulase secretion in Δclr-1 and Δclr-2 strains, growth and hemicellulase secretion were normal on xylan. These results are in contrast to the function of XlnR/XYR1 in Aspergilli and H. jecorina, where this transcription factor is necessary for regulation of some cellulase and hemicellulase genes (3, 30). However, a XlnR/XYR1 homolog is not necessary for cellulase gene expression or activity in N. crassa or Fusarium species (12–14). In these species, XlnR/XYR1 homologs regulate the expression of hemicellulase genes and are required for utilization of hemicellulose. These data suggest that some fungal species have evolved independent mechanisms for expression of cellulase and hemicellulases genes in response to distinct inducers from cellulose or hemicellulose. CLR-1 and CLR-2 are apparently components of such a specific pathway for cellulose sensing in N. crassa.

Cellobiose and its transglycosylation products have been considered the primary inducing molecules for fungal cellulases (9, 32). In this study, the Δclr-1 mutant grew poorly on cellobiose, suggesting that CLR-1 is a crucial element in N. crassa’s cellobiose sensing mechanism. Under this model (Fig. 5), CLR-1 is activated for induction of its target genes in the presence of cellobiose or its products. Activated CLR-1 promotes expression of several genes necessary for efficient import and utilization of cellobiose, as well as that of clr-2. CLR-2 then directly induces cellulase and select hemicellulase gene expression, possibly in a heterocomplex with activated CLR-1.

Homologs of clr-1 and clr-2 are present in genomes of filamentous ascomycete fungi, particularly those in association with plants, suggesting conserved regulatory mechanisms associated with genes within the Avicel regulon. In support of this hypothesis, deletion mutants for the A. nidulans clr-1 and clr-2 homologs (clrA and clrB, respectively) revealed both conserved and divergent aspects. Induction of cellulase genes required clrB but not clrA. However, ΔclrA was deficient for cellobiose utilization. Thus, ClrA may have a conserved role in filamentous ascomycete species in a cellobiose-sensing pathway. Similar to N. crassa clr-2, in A. nidulans, clrB was absolutely required for cellulolytic activity. However, in Aspergilli XlnR also regulates expression of some cellulase genes (5). These data suggest diversity in the signaling pathways that activate cellulases through XlnR and ClrB in filamentous fungi. Further comparisons of the CLR-1/CLR-2 and XlnR regulons in diverse filamentous fungi will define conserved and divergent features associated with regulation of genes involved in plant cell-wall deconstruction.

We identified a 212-gene set that specifically responded to crystalline cellulose (Avicel regulon) with a majority of this gene set requiring clr-1, clr-2, or both to reach WT-induced expression levels. This gene set likely comprises the essential core structural and enzymatic components for efficient degradation of cellulose. The gene set not only includes all highly expressed cellulase genes, but many hemicellulase genes, indicating that complimentary enzymatic activities are required to effectively degrade complex substrates (33). In addition, dozens of secreted proteins with no predicted function or only a broad homology-based annotation showed clr-dependent induction. Homology searches with N. crassa genes within the Avicel regulon against the A. nidulans and H. jecorina genomes showed that many of these genes are conserved (Dataset S1). This collection of proteins provides a rich source for identification of new enzymes with synergistic activities on complex substrates, as recently demonstrated (20, 21). Interestingly, included in this gene set were some well-characterized proteins with functions in secretion, suggesting that modification of the N. crassa secretory pathway is needed to accommodate the dramatic increase in protein secretion that accompanies cellulosic metabolism.

Promoter analyses did not reveal a statistically significantly enriched binding motif in clr-dependent genes. Full genome analyses of DNA binding interactions by ChIP-Seq of both CLR-1 and CLR-2 in context with other transcriptional activators, such as the XlnR homolog in N. crassa (xlr-1) (14), will elucidate the molecular mechanism of induction and regulation of genes involved in plant cell-wall deconstruction. Further characterization and manipulation of the components of the cellulase regulatory network will enable rational engineering of more diverse and productive industrial strains for cellulolytic enzyme production.

Materials and Methods

Strains.

The WT reference strain and background for all N. crassa mutant strains was FGSC 2489 (22). Deletion strains for clr-1 and clr-2 (FGSC 11029 and FGSC 15835, respectively) were obtained from the Fungal Genetics Stock Center (http://www.fgsc.net/) (34). The A. nidulans reference strain was FGSC 4A. Gene deletions in A. nidulans were carried out by transforming FGSC A1149 (pyrG89; pyroA4; nkuA::argB) by established protocols (35). Transformants were crossed to LO1496 (fwA1, pyrG89, nicA2, pabaA1, from Berl R. Oakley Department of Molecular Biosciences, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS) to remove nkuA::argB and pyroA4.

Culture Conditions.

N. crassa cultures were grown on Vogel’s minimal medium (VMM) (36). Carbon sources were 2% wt/vol unless otherwise noted. Conidia were inoculated into 100 mL liquid media at 106 conidia/mL and grown at 25 °C in constant light and shaking (200 rpm). A. nidulans cultures were grown on minimal medium (MM) (37). Carbon sources were 1% wt/vol unless otherwise noted. Conidia were inoculated into 100 mL liquid media at 4 × 106 conidia/mL and grown at 37 °C in constant light and shaking (200 rpm).

Media Shift Experiments.

N. crassa cultures were grown 16 h on VMM, centrifuged at 2,390 × g for 10 min, and washed with VMM (36) without a carbon source. Mycelia were resuspended in 100 mL VMM with 2% (wt/vol) carbon source [sucrose, cellulose (Avicel PH-101; Sigma-Aldrich) or hemicellulose (beechwood xylan, Sigma-Aldrich)] or with no carbon source added. Total RNA was extracted as described in ref. 6. For enzyme activity assays, culture supernatants were sampled at 24 and 48 h, centrifuged at 2,390 × g twice to remove mycelia, and stored at 4 °C for analysis within 24 h.

A. nidulans cultures were grown 16–17 h on MM-glucose. A 15 mL sample was taken at time 0. The remaining culture was filtered through miracloth, washed, and transferred to 100 mL MM containing 1% Avicel. RNA was extracted as above and mRNA abundance was compared between the 8 h and time 0 samples by quantitative RT-PCR (38). Fold-induction was calculated as the ratio of the mRNA level normalized to act A at 8 h vs. act A at time 0. For enzyme activity assays, culture supernatants were sampled at 48–120 h, centrifuged at 2,390 × g twice to remove mycelia and stored at 4 °C for analysis.

RNA Sequencing and Transcript Abundance.

Libraries were prepared with standard protocols from Illumina and sequenced on the Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx and HiSEq 2000 platforms (SI Materials Methods). Sequenced libraries were mapped against predicted transcripts from the N. crassa OR74A genome (39) (v10) with Tophat v1.2.0 (40). Transcript abundance (FPKM, fragments per kilobase unique exon sequence per megabase of library mapped) was estimated with Cufflinks v0.9.3 (41) using upper quartile normalization and mapping against reference isoforms. Profiling data are available in Dataset S1 and at the Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; accession no. GSE35227).

Independent triplicate cultures were sampled and analyzed for the WT strain on Avicel, sucrose, and no carbon at 4 h after the media shift. Raw counts for reads mapping to unique exons were tallied with HTSEq (42) and used as inputs for both the EdgeR and DESeq software packages. Genes with a multiple-hypothesis–adjusted P value below 0.05 from both models were taken as differentially expressed between conditions.

FPKM of genes in the Avicel regulon were hierarchically clustered with the Cluster 3.0 software suite (http://bonsai.hgc.jp/∼mdehoon/software/cluster/software.htm). Before clustering, FPKMs were log-transformed, normalized across strains/conditions, and centered on the geometric mean across strains/conditions on a per-gene basis. The average linkage method was used for cluster generation, with uncentered correlation as the similarity metric.

Enzyme Activity Assays.

Relative enzymatic activity of culture supernatants was assayed with Remazol brilliant Blue R-conjugated CMC and xylan (birchwood) kits from Megazyme. Total protein was determined with the Bradford assay (BioRad).

Statistical Significance Tests.

Unless otherwise noted, all statistical significance tests were done with a one-tailed homoscedastic (equal variance) t-test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Spencer Diamond for his work on the initial screens of putative Neurospora crassa transcription factor mutants on cellulosic substrates. This work was supported by a grant from the Energy Biosciences Institute and a Miller Institute Professorship (to N.L.G.) and National Institutes of Health National Research Service Award Trainee Grant 2 T32 GM 7127-36 A1 (to S.T.C.). We are pleased to acknowledge use of materials generated by P01 GM068087 Functional analysis of a model filamentous fungus.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The profiling data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GSE35227) and RNA-Seq data are listed in Dataset S1.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1200785109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Himmel ME, et al. Biomass recalcitrance: Engineering plants and enzymes for biofuels production. Science. 2007;315:804–807. doi: 10.1126/science.1137016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jordan DB, et al. Plant cell walls to ethanol. Biochem J. 2012;442:241–252. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kubicek CP, Mikus M, Schuster A, Schmoll M, Seiboth B. Metabolic engineering strategies for the improvement of cellulase production by Hypocrea jecorina. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2009;2:19. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-2-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ilmén M, Saloheimo A, Onnela ML, Penttilä ME. Regulation of cellulase gene expression in the filamentous fungus Trichoderma reesei. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1298–1306. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.4.1298-1306.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gielkens MM, Dekkers E, Visser J, de Graaff LH. Two cellobiohydrolase-encoding genes from Aspergillus niger require D-xylose and the xylanolytic transcriptional activator XlnR for their expression. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4340–4345. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.10.4340-4345.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tian C, et al. Systems analysis of plant cell wall degradation by the model filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:22157–22162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906810106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stricker AR, Mach RL, de Graaff LH. Regulation of transcription of cellulases- and hemicellulases-encoding genes in Aspergillus niger and Hypocrea jecorina (Trichoderma reesei) Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;78:211–220. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandels M, Reese ET. Induction of cellulase in Trichoderma viride as influenced by carbon sources and metals. J Bacteriol. 1957;73:269–278. doi: 10.1128/jb.73.2.269-278.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandels M, Reese ET. Induction of cellulase in fungi by cellobiose. J Bacteriol. 1960;79:816–826. doi: 10.1128/jb.79.6.816-826.1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandels M, Parrish FW, Reese ET. Sophorose as an inducer of cellulase in Trichoderma viride. J Bacteriol. 1962;83:400–408. doi: 10.1128/jb.83.2.400-408.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Peij NN, Gielkens MM, de Vries RP, Visser J, de Graaff LH. The transcriptional activator XlnR regulates both xylanolytic and endoglucanase gene expression in Aspergillus niger. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3615–3619. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3615-3619.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brunner K, Lichtenauer AM, Kratochwill K, Delic M, Mach RL. Xyr1 regulates xylanase but not cellulase formation in the head blight fungus Fusarium graminearum. Curr Genet. 2007;52:213–220. doi: 10.1007/s00294-007-0154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calero-Nieto F, Di Pietro A, Roncero MI, Hera C. Role of the transcriptional activator xlnR of Fusarium oxysporum in regulation of xylanase genes and virulence. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2007;20:977–985. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-8-0977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun J, Tian C, Diamond S, Glass NL. Deciphering transcriptional regulatory mechanisms associated with hemicellulose degradation in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot Cell. 2012;11:482–493. doi: 10.1128/EC.05327-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aro N, Saloheimo A, Ilmén M, Penttilä M. ACEII, a novel transcriptional activator involved in regulation of cellulase and xylanase genes of Trichoderma reesei. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24309–24314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003624200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turner BC, Perkins DD, Fairfield A. Neurospora from natural populations: A global study. Fungal Genet Biol. 2001;32:67–92. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.2001.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis RH, Perkins DD. Timeline: Neurospora: A model of model microbes. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:397–403. doi: 10.1038/nrg797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phillips CM, Iavarone AT, Marletta MA. Quantitative proteomic approach for cellulose degradation by Neurospora crassa. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:4177–4185. doi: 10.1021/pr200329b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galazka JM, et al. Cellodextrin transport in yeast for improved biofuel production. Science. 2010;330:84–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1192838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips CM, Beeson WT, Cate JH, Marletta MA. Cellobiose dehydrogenase and a copper-dependent polysaccharide monooxygenase potentiate cellulose degradation by Neurospora crassa. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6:1399–1406. doi: 10.1021/cb200351y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beeson WT, Phillips CM, Cate JH, Marletta MA. Oxidative cleavage of cellulose by fungal copper-dependent polysaccharide monooxygenases. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:890–892. doi: 10.1021/ja210657t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colot HV, et al. A high-throughput gene knockout procedure for Neurospora reveals functions for multiple transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10352–10357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601456103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aro N, Ilmén M, Saloheimo A, Penttilä M. ACEI of Trichoderma reesei is a repressor of cellulase and xylanase expression. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:56–65. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.1.56-65.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeilinger S, Mach RL, Kubicek CP. Two adjacent protein binding motifs in the cbh2 (cellobiohydrolase II-encoding) promoter of the fungus Hypocrea jecorina (Trichoderma reesei) cooperate in the induction by cellulose. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:34463–34471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lockington RA, Rodbourn L, Barnett S, Carter CJ, Kelly JM. Regulation by carbon and nitrogen sources of a family of cellulases in Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genet Biol. 2002;37:190–196. doi: 10.1016/s1087-1845(02)00504-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tilburn J, et al. The Aspergillus PacC zinc finger transcription factor mediates regulation of both acid- and alkaline-expressed genes by ambient pH. EMBO J. 1995;14:779–790. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07056.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun J, Glass NL. Identification of the CRE-1 cellulolytic regulon in Neurospora crassa. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e25654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacPherson S, Larochelle M, Turcotte B. A fungal family of transcriptional regulators: the zinc cluster proteins. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:583–604. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00015-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruepp A, et al. The FunCat, a functional annotation scheme for systematic classification of proteins from whole genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5539–5545. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stricker AR, Grosstessner-Hain K, Würleitner E, Mach RL. Xyr1 (xylanase regulator 1) regulates both the hydrolytic enzyme system and D-xylose metabolism in Hypocrea jecorina. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:2128–2137. doi: 10.1128/EC.00211-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLaughlin DJ, Hibbett DS, Lutzoni F, Spatafora JW, Vilgalys R. The search for the fungal tree of life. Trends Microbiol. 2009;17:488–497. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Znameroski EA, et al. Induction of lignocellulose degrading enzymes in Neurospora crassa by cellodextrins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:6012–6017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118440109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benko Z, Siika-aho M, Viikari L, Reczey K. Evaluation of the role of xyloglucanase in the enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulosic substrates. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2008;43(2):109–114. [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCluskey K. The Fungal Genetics Stock Center: From molds to molecules. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2003;52:245–262. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2164(03)01010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szewczyk E, et al. Fusion PCR and gene targeting in Aspergillus nidulans. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:3111–3120. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vogel HJ. A convenient growth medium for Neurospora. Microbiol Genet Bull. 1956;13:42–46. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vishniac W, Santer M. The thiobacilli. Bacteriol Rev. 1957;21:195–213. doi: 10.1128/br.21.3.195-213.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galagan JE, et al. The genome sequence of the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa. Nature. 2003;422:859–868. doi: 10.1038/nature01554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roberts A, Trapnell C, Donaghey J, Rinn JL, Pachter L. Improving RNA-Seq expression estimates by correcting for fragment bias. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R22. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-3-r22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cantarel BL, et al. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): An expert resource for Glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D233–D238. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: A bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.