Abstract

The Tibetan Plateau is the youngest and highest plateau on Earth, and its elevation reaches one-third of the height of the troposphere, with profound dynamic and thermal effects on atmospheric circulation and climate. The uplift of the Tibetan Plateau was an important factor of global climate change during the late Cenozoic and strongly influenced the development of the Asian monsoon system. However, there have been heated debates about the history and process of Tibetan Plateau uplift, especially the paleo-altimetry in different geological ages. Here we report a well-preserved skeleton of a 4.6 million-y-old three-toed horse (Hipparion zandaense) from the Zanda Basin, southwestern Tibet. Morphological features indicate that H. zandaense was a cursorial horse that lived in alpine steppe habitats. Because this open landscape would be situated above the timberline on the steep southern margin of the Tibetan Plateau, the elevation of the Zanda Basin at 4.6 Ma was estimated to be ∼4,000 m above sea level using an adjustment to the paleo-temperature in the middle Pliocene, as well as comparison with modern vegetation vertical zones. Thus, we conclude that the southwestern Tibetan Plateau achieved the present-day elevation in the mid-Pliocene.

Keywords: vertebrate paleontology, paleoecology, stable isotope, tectonics

Fossils of the three-toed horse genus Hipparion that have been found on the Tibetan Plateau have provided concrete evidence for studying the uplift of the plateau (1–3), including a skull with associated mandible of Hipparion zandaense within the subgenus Plesiohipparion from Zanda (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1). In August 2009 a Hipparion skeleton (Fig. 2) was excavated from Zanda Basin, with IVPP (Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences) catalog number V 18189 (see Table S1 for a composite list of vertebrate taxa from the Zanda strata). Its dental morphology confirmed its assignment to H. zandaense, and its postcranial morphology is very similar to another species of the Plesiohipparion group, Hipparion houfenense (see SI Text and Figs. S2–S5). Paleomagnetic dating showed that the Zanda Formation was deposited 6.15–3.4 Ma, in which the fossiliferous bed-bearing H. zandaense has an age of about 4.6 Ma, corresponding to the middle Pliocene (SI Text).

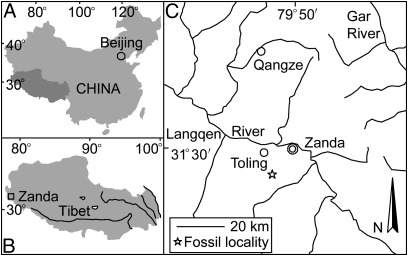

Fig. 1.

Location map showing the study site (C) of the Zanda Basin (B) in Tibet, China (A).

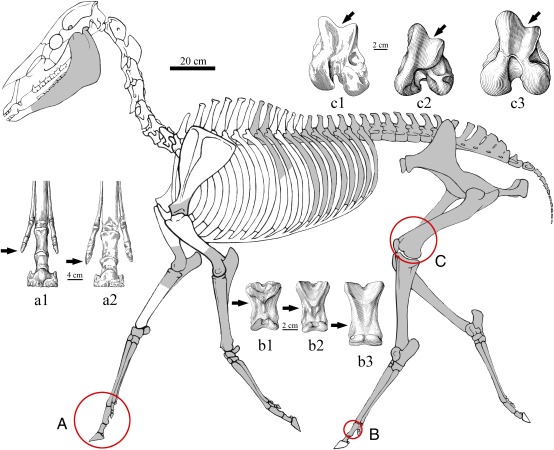

Fig. 2.

Hipparion zandaense skeleton (IVPP V 18189) and comparisons of forefeet (A), femora (C), and hind first Ph III (B). Reconstruction of skeleton showing preserved bones in dark gray. a1, Hipparion zandaense; a2, H. primigenium (9); b1, H. xizangense; b2, H. zandaense; b3, Equus caballus; c1, H. primigenium (9); c2, H. zandaense; c3. E. caballus.

Geological Setting

The Zanda Basin is a late-Cenozoic sedimentary basin located just north of the high Himalayan ridge crest in the west-central part of the orogen (32° N, 80° E). The Sutlej River has incised through to the basement, exposing the entire basin fill in a spectacular series of canyons and cliffs (4). The Zanda Basin stretches in a NW-SE direction, and is 150 km long and 20–50 km wide. The almost horizontal strata of the Zanda Basin, superposed on Jurassic and Cretaceous shale and limestone, consist of weakly consolidated clastic rocks of up to 800 m in thickness (5). A single unit, the Zanda Formation, is used for the entire Neogene sequence in this basin (SI Text). The Hipparion skeleton was discovered in the eastern bank (Fig. 1) of the main wash of Daba Canyon west of the Zanda county seat and south of the Sutlej River.

Description

Because both morphology and attachment impressions on fossilized bones can reflect muscular and ligamentous situations, they can provide evidence for the type of locomotion that extinct animals use when they lived. The skeleton of H. zandaense preserved all limb bones, pelvis, and partial vertebrae (Fig. 2), which provide an opportunity to reconstruct its locomotive function.

A greatly hypertrophied medial trochlear ridge (MTR, black arrows in Fig. 2, c1–c3) of the femur serves to “snag” the medial patellar ligament, or parapatellar cartilage, and the patella when the knee joint is hyperextended (6), forming a passive stay-apparatus or “locking” to reduce muscular activity in the knee extensors during long periods of standing. The well-developed MTR is an indicator of the presence of this locking mechanism (7). The femur MTR of H. zandaense is greatly enlarged relative to the lateral trochlear ridge (Fig. 2, c2). Like modern horses (Fig. 2, c3), which may stand erect for over 20 h a day, even in their sleep (8), H. zandaense could remain on its feet for long periods of time without fatigue. The femur MTR in Hipparion primigenium (Fig. 2, c1) is obviously smaller than in H. zandaense. The ratio between the maximum depth of the MTR and the maximum length of the femur is 0.27 in H. primigenium (9), whereas the ratio is 0.3 in H. zandaense.

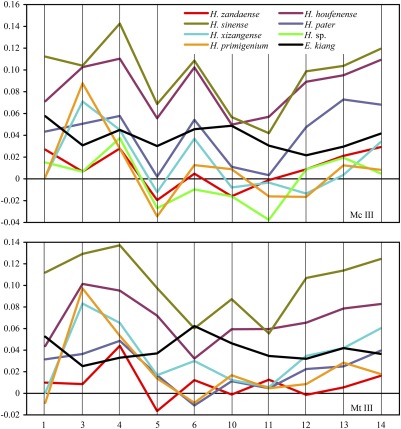

Gracile limb bones are a marker for cursorial ability, which is most clearly exhibited on metapodials of ungulates (10). The gracility of the metapodial shaft is represented by diminished breadth relative to its length. In Fig. 3, above the zero line are the comparatively larger measurements and below it are the smaller ones. The ratio between the maximum length and the minimum breadth indicates that H. zandaense, Hipparion sp. from Kirgiz Nur, Mongolia, and the extant Tibetan wild ass have relatively slender metapodials (measurement 3 is smaller or slightly larger than measurement 1), but the primitive H. primigenium and Hipparion xizangense have very robust metapodials (measurement 3 is obviously larger than measurement 1), and the subgenus Proboscidipparion (Hipparion sinense and Hipparion pater) and H. houfenense in the North China Plain also show increased robustness (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Ratio diagrams of metapodials of H. zandaense and other equids. H. sp.: Hipparion sp. from Kirgiz Nur, Mongolia. Measurement numbers: 1, maximal length; 3, minimal breadth; 4, depth of the shaft; 5, proximal articular breadth; 6, proximal articular depth; 10, distal maximal supra-articular breadth; 11, distal maximal articular breadth; 12, distal maximal depth of the keel; 13, distal minimal depth of the lateral condyle; 14, distal maximal depth of the medial condyle. The y axis is the logarithm (base 10) of ratios between the measurements of each species and the reference species (Asiatic wild ass Equus hemionus onager, zero line).

During the evolution of increased cursoriality in horses, the posterior shifting of the lateral metapodials relative to the third metapodial is not only an evolutionary change toward functional monodactyly, but also a better adaptation for running, usually accompanied by a deepening of the whole bone and an effacement of the distal supra-articular tuberosity. As a result, the width of the distal tuberosity appears reduced relative to the articular width (11). The width of the distal tuberosity of the metapodials is much smaller than the width of the distal articulation in H. zandaense, whereas the former is larger than the latter in H. primigenium (Tables S2 and S3). The distal articulation of metapodials in H. zandaense is wider than those in H. primigenium and H. xizangense (Fig. 3, measurement 11 is comparatively larger), but the width of the distal tuberosity in H. zandaense is narrower than in the other two species (Fig. 3, measurement 10 is comparatively smaller).

The well-developed sagittal keel on the distal extremity of the metapodial is another character to enhance pendular movement of limb bones and an adaptation for running (12). The development of the keel is relative to the deepening of the distal lateral groove, and is accompanied with the thickening of the medial condyle. These changes diminish lateral mobility and create better conditions for anteroposterior movements (13). The sagittal groove of the first phalanx III contains the keel of the distal articulation of the metapodial to avoid dislocation and sprain of the joint in lateral orientation, especially during rapid turning (11). The ratio between the depth of the lateral groove and the thickness of the keel on the distal extremity of metacarpal III is 0.84 in H. zandaense, but 0.88 in H. primigenium, and the ratio between the dorsal length and the total length of the first phalanx III is 0.92 in H. zandaense, but 0.94 in H. primigenium, which reflects a stronger keel for H. zandaense, so it can better minimize the lateral movement of the foot articulation, thereby strengthening the anteroposterior movement more effectively.

In Hipparion, the increase in size of the oblique ligaments on the proximal and central phalanx may have allowed the central toe to stand more vertically, thus causing the side toes to be lifted from the ground and become nonfunctional in locomotion, allowing the animal to run faster by supporting the fetlock and by adding bounce (14). The V-scars of H. xizangense (Fig. 2, b1) (2) and H. primigenium (9) are less developed on both fore and hind phalanx III, whereas that of H. zandaense is much wider and flatter (Fig. 2, b2), more similar to Equus (Fig. 2, b3).

In hipparionine horses, each foot has three toes (digits II to IV); digits I and V are absent. The reduction of the side toes (digits II and IV) in horses is a marked evolutionary trend toward better running ability (15). H. primigenium has evolved to use the unique functional central toe (digit III) during running, but all three toes may be used during slow walking, the latter being the more deliberate movement of H. primigenium (9). The side toes of H. zandaense are more distinctly reduced. For example, the total length of the three fore phalanges II of H. zandaense is 67.4 mm, whereas that of H. primigenium is 78.8 mm. Digit III of H. zandaense is also slightly longer than that of H. primigenium, so the side toes of the former have a larger suspending extent (Fig. 2A). This character indicates that the side toes of H. zandaense have completely lost locomotive function, a characteristic related to faster running.

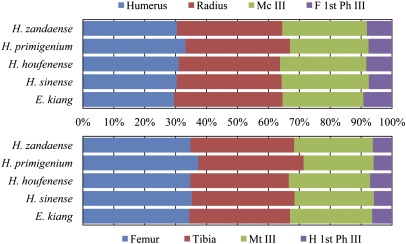

If distal elements of a limb are lengthened relative to proximal ones, the whole limb will be lengthened, yet keep its center of mass situated proximally and reduce its inertia, which allows for a long, rapid stride; speed is the product of stride length and stride frequency (16). Lengths of distal elements of fore- and hindlimbs (i.e., metapodials and first phalanges), relative to proximal elements in H. zandaense are much longer than in H. primigenium (Fig. 4), which indicates the stronger running ability of the former. Both the advanced H. houfenense and H. sinense have these characteristics.

Fig. 4.

Proportions of limb bones in H. zandaense and other equids.

Discussion

The preceding analysis of locomotive function shows that H. zandaense had the ability to run fast and stand persistently, which is beneficial only on open habitats, because close forests would encumber running. Hipparionine horses are typical hypsodont ungulates, and the tooth crowns of the subgenus Plesiohipparion are especially high (17), which indicate that they are grass-grazing specialists (10). Because grazing is inefficient in terms of nutritional intake, a great amount of food is required to obtain adequate nutrients (18). Grazing horses spend a large portion of the day standing and eating in open habitats with mainly herbaceous plants, so that they can keep watch for potential predators. The well-developed MTR of the femur in H. zandaense is a fitting adaptation for this ecosystem (7). The vestigial side toes of H. zandaense also reflect its adaptation for open environments instead of forests. The running ability of H. primigenium is weaker and more suitable to slower movement in closed habitats (i.e., woodland or forest) (9, 11), and its locomotive function stands in contrast to the inferred ecosystem and behavior of H. zandaense. Other mid-Pliocene mammalian forms from Zanda also indicate an open landscape (19).

The Tibetan Plateau is the youngest and highest plateau on Earth, and its elevation reaches one-third of the height of the troposphere, with profound dynamic and thermal effects on atmospheric circulation and climate (20, 21). The uplift of the Tibetan Plateau was an important factor of global climate change during the late Cenozoic and strongly influenced the development of the Asian monsoon system (22, 23). However, there have been heated debates about the history and process of Tibetan Plateau uplift, especially the paleo-altimetry in different geological ages (24–27). The Tibetan Plateau has gradually risen since the Indian plate collided with the Eurasian plate at about 55 Ma. Regardless of the debates over the rising process and elevation of the plateau (26–28), there is no doubt that the Himalayas have appeared as a mountain range since the Miocene, with the appearance of vegetation vertical zones following thereafter (29). Open grasslands per se have no direct relationship to elevation, because they can have different elevations in different regions of the world, having a distribution near the sea level to the extreme high plateaus. Controlled by the subduction zone, on the other hand, the southern margin of the Tibetan Plateau has been high and steep to follow the uplift of this plateau so that the open landscape must be above the timberline in the vegetation vertical zones. Because the Zanda Basin is located on the south edge of the Tibetan Plateau, its vegetation ecosystem is tightly linked to the established vertical zones along the Himalayas. In the Zanda area, the modern timberline is at an elevation of 3,600 m between the closed forest and the open steppe (30). Our locomotive analysis indicates that H. zandaense was more suited to live in an open environment above the timberline, as opposed to a dense forest. The inference of high-elevation open habitat is supported by the carbon isotope data. The δ13C values of tooth enamel from modern and fossil herbivores indicate that the mid-Pliocene horses, like modern wild Tibetan asses, fed on C3 vegetation (Fig. S6A). Although carbon isotope analysis of fossil plant materials in the basin showed that C4 grasses (warm climate grasses) were present in local ecosystems in the latest Miocene and Pliocene (4), our enamel δ13C data show that C4 grasses must have been a minor component of local ecosystems since the mid-Pliocene because they were insignificant in the diets of local herbivores. The pure C3 diets indicate that grasses ingested by these animals were cool-season grasses commonly found in high-elevation ecosystems.

The mid-Pliocene global climate was significantly warmer than the Holocene, whereas crucial boundary conditions, such as the placement of continents, were about the same as today (31). Therefore, it was likely that temperature (32), instead of longitude and latitude, was the main factor in determining the timberline of the Himalayas in the Pliocene when global surface temperatures were between 2 °C and 3 °C warmer than present (33). Based on the marine record (34), the temperature of the mid-Pliocene was ∼2.5 °C warmer than today, and consequently the elevation of the timberline in the Zanda area at 4.6 Ma was 400 m higher than the modern one of 3,600 m, assuming a temperature lapse rate of 0.6 °C/100 m applies to the past. This finding suggests that the Zanda Basin had achieved an elevation comparable to its present-day elevation by 4.6 Ma.

The material of H. xizangense from Biru, Tibet includes limb bones, especially distal elements, with an age of early Late Miocene at about 10 Ma (2). The metapodial proportions of H. xizangense are nearly identical to those of H. primigenium (Fig. 3), indicating their common locomotive function, which means that H. xizangense was a woodland-forest horse and lived in a habitat with a lower elevation. Hipparion forstenae from Gyirong, Tibet is represented by skulls and mandibles, but lacking limb bones, with an age of late Late Miocene at 7.0 Ma (1, 17). H. forstenae was widely distributed in Gansu and Shanxi provinces in eastern China with a lower elevation, so this species would have lived in similar environments in Gyirong (27). Therefore, Hipparion fossils of different ages from three localities in Biru, Gyirong, and Zanda have been clear to reflect the progress and magnitude of the uplift of the Tibetan Plateau since the Late Miocene.

The limb bones of the Tibetan wild ass, which lives in the Tibetan Plateau today, are very close in proportion to H. zandaense, especially the gracility of their metapodials. Both of Equus kiang and H. zandaense are different from the open plain adapted H. houfenense, and more distinct from the forest adapted H. primigenium and H. xizangense (Figs. 3 and 4). Judged from this situation, H. zandaense and E. kiang took a convergent evolutionary path in morphological function, having both lived in the same plateau environment. These shared features further support our conclusion that the paleo-environment and paleo-elevation estimations for H. zandaense are reasonable.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Zhao, C.-F. Zhang, and B.-Y. Sun for their participation in the field work; and F.-Q. Shi for preparation of Zanda fossils. This work was supported by Chinese Academy of Sciences Grant KZCX2-YW-Q09, National Basic Research Program of China Grant 2012CB821906, Chinese National Natural Science Foundation Grants 40730210 and 40702004, National Geographic Society Grant W22-08, and National Science Foundation Grants EAR-0446699 and EAR-0444073. Isotope analysis was performed at the Florida State University Stable Isotope Laboratory supported by National Science Foundation Grants EAR-0517806 and EAR-0236357.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1201052109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ji HX, Hsu CQ, Huang WP. Chinese Academy of Sciences . Palaeontology of Xizang, Book 1. Beijing: Science Press; 1980. The Hipparion fauna from Guizhong Basin, Xizang; pp. 18–32. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng SH. Chinese Academy of Sciences . Palaeontology of Xizang, Book 1. Beijing: Science Press; 1980. The Hipparion fauna of Bulong Basin, Biru, Xizang; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li FL, Li DL. Latest Miocene Hipparion (Plesiohipparion) of Zanda Basin. In: Yang ZY, Nie ZT, editors. Paleontology of the Ngari Area, Tibet (Xizang) Wuhan: China Univ Geoscience Press; 1990. pp. 186–193. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saylor JE, et al. The late Miocene through present paleoelevation history of southwestern Tibet. Am J Sci. 2009;309:1–42. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang SF, Zhang WL, Fang XM, Dai S, Kempf O. Magnetostratigraphy of the Zanda Basin in southwest Tibet Plateau and its tectonic implications. Chin Sci Bull. 2008;53:1393–1400. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sack WO. The stay-apparatus of the horse’s hindlimb, explained. Equine Pract. 1988;11:31–35. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hermanson J, MacFadden BJ. Evolutionary and functional morphology of the knee in fossil and extant horses (Equidae) J Vert Paleont. 1996;16:349–357. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyd LE, Carbonaro DA, Houpt KA. The 24-hour time budget of Przewalski horses. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1988;21:5–17. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernor RL, Tobien H, Hayek LAC, Mittmann HW. Hippotherium primigenium (Equidae, Mammalia) from the late Miocene of Höwenegg (Hegao, Germany) Andrias. 1997;10:1–230. [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacFadden BJ. Fossil Horses: Systematics, Paleobiology, and Evolution of the Family Equidae. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisenmann V. What metapodial morphometry has to say about some Miocene Hipparions. In: Vrba ES, Denton GH, Partridge TC, Burckle LH, editors. Paleoclimate and Evolution, with Emphasis on Human Origins. New Haven: Yale Univ Press; 1995. pp. 148–164. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisenmann V, Sondaar PY. Hipparions and the Mio-Pliocene boundary. Boll Soc Paleont Ital. 1989;28:217–226. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hussain ST. Evolutionary and functional anatomy of the pelvic limb in fossil and recent Equidae (Perissodactyla, Mammalia) Anat Histol Embryol. 1975;4:179–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0264.1975.tb00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camp CL, Smith N. Phylogeny and functions of the digital ligaments of the horse. Univ California Mem. 1942;13:69–124. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evander RL. Phylogeny of the family Equidae. In: Prothero DR, Schoch RM, editors. The Evolution of Perissodactyls. New York: Oxford Univ Press; 1989. pp. 109–127. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomason JJ. The functional morphology of the manus in tridactyl equids Merychippus and Mesohippus: Paleontological inferences from neontological models. J Vert Paleont. 1986;6:143–161. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiu ZX, Huang WL, Guo ZH. The Chinese hipparionine fossils. Palaeont Sin New Ser C. 1987;25:1–243. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janis CM. The evolutionary strategy of the Equidae and the origins of rumen and cecal digestion. Evolution. 1976;30:757–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1976.tb00957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng T, et al. Out of Tibet: Pliocene woolly rhino suggests high-plateau origin of Ice Age megaherbivores. Science. 2011;333:1285–1288. doi: 10.1126/science.1206594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burbank DW, Derry LA, France-Lanord C. Reduced Himalayan sediment production 8 Myr ago despite an intensified monsoon. Nature. 1993;364:48–50. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang P, Molnar P, Downs WR. Increased sedimentation rates and grain sizes 2-4 Myr ago due to the influence of climate change on erosion rates. Nature. 2001;410:891–897. doi: 10.1038/35073504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raymo ME, Ruddiman WF. Tectonic forcing of late Cenozoic climate change. Nature. 1992;359:117–122. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo ZT, et al. Onset of Asian desertification by 22 Myr ago inferred from loess deposits in China. Nature. 2002;416:159–163. doi: 10.1038/416159a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Molnar P, England P, Martinod J. Mantle dynamics, uplift of the Tibetan Plateau and the Indian monsoon. Rev Geophys. 1993;31:357–396. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spicer RA, et al. Constant elevation of southern Tibet over the past 15 million years. Nature. 2003;421:622–624. doi: 10.1038/nature01356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rowley DB, Currie BS. Palaeo-altimetry of the late Eocene to Miocene Lunpola basin, central Tibet. Nature. 2006;439:677–681. doi: 10.1038/nature04506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, Deng T, Biasatti D. Ancient diets indicate significant uplift of southern Tibet after ca. 7 Ma. Geology. 2006;34:309–312. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harrison TM, Copeland P, Kidd WS, Yin A. Raising tibet. Science. 1992;255:1663–1670. doi: 10.1126/science.255.5052.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu ZY. Origin and evolution of the flora of Tibet. In: Wu ZY, editor. Flora of Xizangica, Vol. 5. Beijing: Science Press; 1987. pp. 874–902. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang XP, Zhang L, Fang JY. Geographical differences in alpine timberline and its climatic interpretation in China. Acta Geogr Sin. 2004;59:871–879. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sabaa AT, Sikes EL, Hayward BW, Howard WR. Pliocene sea surface temperature changes in ODP Site 1125, Chatham Rise, east of New Zealand. Mar Geol. 2004;205:113–125. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tranquillni W. Physiological Ecology of the Alpine Timberline. Berlin: Springer; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dowsett HJ. The PRISM paleoclimate reconstruction and Pliocene sea-surface temperature. Micropaleont Soc Spec Pub. 2007;2:459–480. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zachos J, Pagani M, Sloan L, Thomas E, Billups K. Trends, rhythms, and aberrations in global climate 65 Ma to present. Science. 2001;292:686–693. doi: 10.1126/science.1059412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.