Abstract

Low nutrient and energy availability has led to the evolution of numerous strategies for overcoming these limitations, of which symbiotic associations represent a key mechanism. Particularly striking are the associations between chemosynthetic bacteria and marine animals that thrive in nutrient-poor environments such as the deep sea because the symbionts allow their hosts to grow on inorganic energy and carbon sources such as sulfide and CO2. Remarkably little is known about the physiological strategies that enable chemosynthetic symbioses to colonize oligotrophic environments. In this study, we used metaproteomics and metabolomics to investigate the intricate network of metabolic interactions in the chemosynthetic association between Olavius algarvensis, a gutless marine worm, and its bacterial symbionts. We propose previously undescribed pathways for coping with energy and nutrient limitation, some of which may be widespread in both free-living and symbiotic bacteria. These pathways include (i) a pathway for symbiont assimilation of the host waste products acetate, propionate, succinate and malate; (ii) the potential use of carbon monoxide as an energy source, a substrate previously not known to play a role in marine invertebrate symbioses; (iii) the potential use of hydrogen as an energy source; (iv) the strong expression of high-affinity uptake transporters; and (v) as yet undescribed energy-efficient steps in CO2 fixation and sulfate reduction. The high expression of proteins involved in pathways for energy and carbon uptake and conservation in the O. algarvensis symbiosis indicates that the oligotrophic nature of its environment exerted a strong selective pressure in shaping these associations.

Keywords: 3-hydroxypropionate bi-cycle, Calvin cycle, proton-translocating pyrophosphatase, pyrophosphate dependent phosphofructokinase, metagenomics

Growth in nutrient-limited environments presents numerous challenges to organisms. Symbiotic and syntrophic relationships have evolved as particularly successful strategies for coping with these challenges. Such nutritional symbioses are widespread in nature and, for example, have enabled plants to colonize nitrogen-poor soils and animals to thrive on food sources that lack essential amino acids and vitamins (1). Chemosynthetic symbioses, discovered only 35 years ago at hydrothermal vents in the deep sea, revolutionized our understanding of nutritional associations, because these symbioses enable animals to live on inorganic energy and carbon sources such as sulfide and CO2 (2, 3). The chemosynthetic symbionts use the energy obtained from oxidizing reduced inorganic compounds such as sulfide to fix CO2, ultimately providing their hosts with organic carbon compounds. Chemosynthetic symbioses thus are able to thrive in habitats where organic carbon sources are rare, such as the deep sea, and the symbionts often are so efficient at providing nutrition that many hosts have reduced their digestive systems (4).

The marine oligochaete Olavius algarvensis is a particularly extreme example of a nutritional symbiosis: These worms are dependent on their chemosynthetic symbionts for both their nutrition and their excretion, because they have reduced their mouth, gut, and nephridial excretory organs completely (5). O. algarvensis lives in coarse-grained coastal sediments off the island of Elba, Italy, and migrates between the upper oxidized and the lower reduced sediment layers (6). It hosts a stable and specific microbial consortium consisting of five bacterial endosymbionts in its body wall: two aerobic or denitrifying gammaproteobacterial sulfur oxidizers (γ1- and γ3-symbionts), two anaerobic deltaproteobacterial sulfate reducers (δ1- and δ4-symbionts), and a spirochete with an unknown metabolism (7, 8). The sulfate-reducing δ-symbionts provide the sulfur-oxidizing γ-symbionts with reduced sulfur compounds as an internal energy source for autotrophic CO2 fixation via the Calvin–Benson cycle, thus explaining how O. algarvensis can thrive in its sulfide-poor environment (6, 9). As in all living organisms, the symbiosis is dependent on external energy sources, but to date the identity of these sources has remained unclear.

Like the vast majority of symbiotic microbes, the O. algarvensis symbionts have defied cultivation attempts, making cultivation-independent techniques essential for their analysis. A metagenomic analysis of the O. algarvensis symbionts yielded initial insights into their potential metabolism (9), but the incomplete genome sequences hindered the reconstruction of complete metabolic pathways, leaving many questions unanswered (10). Furthermore, as in all genomic analyses, detailed insights into the physiology and metabolism of an organism are limited, because these analyses can predict only the metabolic potential of an organism, not its actual metabolism and physiology (11). This limitation is most apparent in a multimember community in which the interactions between the different members and between these members and their environment lead to a level of metabolic complexity that can greatly exceed the predictive ability of genomic reconstructions from single species.

Although metagenomic analyses reveal the metabolic potential of a microbial community, metaproteomic and metabolomic analyses provide evidence for the metabolic and physiological processes that actually are used by the community. In this study, we used metaproteomics and metabolomics as well as enzyme assays and in situ analyses of potential energy sources to gain an in-depth understanding of the intricate interactions between O. algarvensis and its microbial symbiont community and between the members of this community and their environment. Our goal was to identify the compounds that provide energy for the symbiosis, the functional roles of the different partners, and their interactions within the symbiosis.

Results and Discussion

High Coverage of the Symbiosis Metaproteome and Metabolome.

We identified and quantified a total of 2,819 proteins and 97 metabolites in O. algarvensis and its symbiotic community (SI Appendix, Tables S1 and S2 and Datasets S1 and S2) using different methods for both the metaproteomic and the metabolomic analyses to overcome the intrinsic biases inherent in a single detection method (SI Appendix, SI Text). For host proteins, sequences from related annelids enabled the cross-species identification of 530 O. algarvensis proteins, thus providing insight into the metabolism of a marine oligochaete, a group of annelid worms for which no genomic data are available. For symbiont proteins, the published O. algarvensis symbiont metagenome, which contains only sequences assigned to specific symbionts through binning analyses (9), led to the identification of 1,586 proteins. The addition of unassigned sequences from the unbinned O. algarvensis symbiont metagenome allowed us to identify a total of 2,265 symbiont proteins, a 43% increase compared with the published metagenome alone. Because of the lack of metagenomic information for the spirochete, no proteins were found that could be assigned unambiguously to the spirochete symbiont of O. algarvensis (9).

To improve coverage of the metaproteome further, we developed a method using density-gradient centrifugation for physical separation of the O. algarvensis symbionts from each other and from host tissues (SI Appendix, SI Text and Fig. S1). This method greatly enhanced the number of identified symbiont proteins, particularly for those present in lower abundances (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Table S1). An additional advantage of symbiont enrichments was that we were able to assign proteins from the unbinned metagenomic sequences to a specific symbiont if they were detected in high abundances in enrichment fractions of the given symbiont (SI Appendix, SI Text). This proteomics-based binning allowed us to assign 544 previously unassigned proteins to a specific symbiont, thus significantly extending our understanding of the symbionts’ metabolism (SI Appendix, Table S3 and Dataset S3).

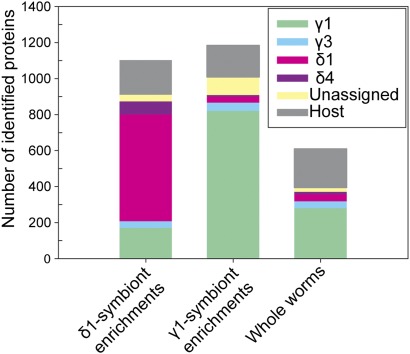

Fig. 1.

Positive effect of symbiont enrichment using density-gradient centrifugation. Enrichment considerably increased the number of identified proteins from a given symbiont compared with analyses of whole worms. Average protein numbers were calculated for 2D LC-MS/MS experiments (SI Appendix, Table S1). n = 2 for γ1-symbiont enrichments; n = 2 for δ1-symbiont enrichments; and n = 4 for whole-worm samples. Both metagenomic and proteomic binning information was used for assignment of proteins to a symbiont.

Energy Sources for the O. algarvensis Symbiosis.

One of the major unresolved questions in the O. algarvensis symbiosis is the identity of the sources of energy from the environment that fuel the association. Earlier studies found that reduced sulfur compounds are supplied internally as an energy source to the aerobic sulfur-oxidizing γ-symbionts by the anaerobic sulfate-reducing δ-symbionts. In return, the δ-symbionts are supplied with oxidized sulfur compounds as electron acceptors (6, 9). Our metaproteomic analyses are consistent with this model of syntrophic sulfur cycling, with abundantly expressed sulfur oxidation proteins detected in the γ-symbionts and sulfate reduction proteins detected in the δ-symbionts (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, SI Text and Figs. S2 and S3A). However, for net growth and compensation of thermodynamic losses, external energy sources are required. Most chemosynthetic symbioses are fueled by an external supply of reduced sulfur compounds. However, concentrations of reduced sulfur compounds are extremely low in the habitat of O. algarvensis (6), indicating that other energy sources play an important role in the symbiosis.

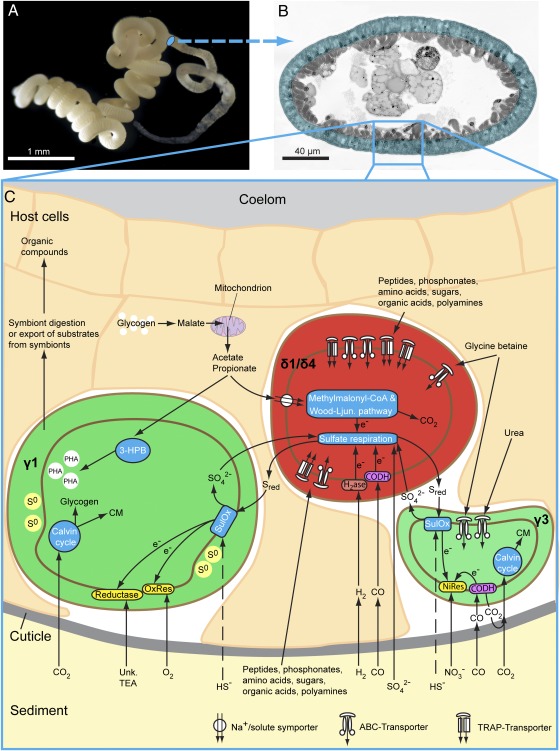

Fig. 2.

Overview of symbiotic metabolism based on metaproteomic and metabolomic analyses. (A) Live O. algarvensis specimen. (B) Light micrograph of a cross section through O. algarvensis. The region containing the symbionts is highlighted in blue. (C) Metabolic reconstruction of symbiont and host pathways. The δ1- and δ4-symbionts are shown as a single cell, because most metabolic pathways were identified in the δ1-symbiont and only a small fraction of the same pathways were identified in the δ4-symbiont because of the low coverage of its metaproteome. 3-HPB, partial 3-hydroxypropionate bicycle; CM, cell material; CODH, carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (aerobic or anaerobic type); NiRes, nitrate respiration; OxRes, oxygen respiration; PHA, polyhydroxyalkanoate granule; S0, elemental sulfur; Sred, reduced sulfur compounds; SulOx, sulfur oxidation; Unk. TEA, unknown terminal electron acceptor.

Carbon monoxide may be used by three symbionts.

Our metaproteomic analyses suggest that three of the O. algarvensis symbionts use carbon monoxide (CO) as an energy source. CO is not known to be used as an electron donor by chemosynthetic symbionts, and its toxicity to aerobic life suggested that this reductant would not play an important role in animal symbioses. We detected both aerobic and anaerobic CO dehydrogenases in the O. algarvensis consortium, the aerobic type in the γ3-symbiont and the anaerobic type in the δ-proteobacterial symbionts [for reviews of aerobic and anaerobic CO oxidation see King and Weber (12) and Oelgeschläger and Rother (13)]. The δ-proteobacterial symbionts express two versions of the anaerobic CO dehydrogenase, one that oxidizes free CO generating a proton gradient across the membrane, and one that likely is involved in the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway and oxidizes enzyme-bound CO (SI Appendix, SI Text).

To support the metaproteomic prediction that CO could be an energy source for the symbiosis, we measured CO concentrations in the O. algarvensis habitat. CO concentrations in the sediment pore waters ranged from 17–46 nM (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). These concentrations are sufficient to support free-living marine CO oxidizers, which can use concentrations of 2–10 nM in surface sea water (14, 15) and about 100 nM at hydrothermal vents (12). Pore water CO concentrations were well above the concentrations in the seawater overlying the sediment (8–16 nM) (SI Appendix, Fig. S4), indicating the presence of a CO source in the sediment. CO can be produced through abiotic and biotic processes from plant roots (16) and from decaying seagrass-derived organic matter (17), which are abundant at the collection site of the worms.

The CO2/CO couple has a very negative redox potential, −520 mV (18), making CO an excellent electron donor whose electrons can be transferred to a variety of terminal electron acceptors such as oxygen, nitrate, elemental sulfur, and sulfate (12, 13, 19). Therefore CO could be used as an energy source by the O. algarvensis symbionts under all redox conditions as the worm shuttles between sediment layers. In the reduced sediment layers, the δ-symbionts could use sulfate for the anaerobic oxidation of CO, thereby producing reduced sulfur compounds for the γ-symbionts; in the oxic and suboxic sediment layers, the γ3-symbiont could oxidize CO with nitrate as a terminal electron acceptor (SI Appendix, SI Text, SI Results and Discussion).

Hydrogen may be used by the sulfate-reducing symbionts.

Our metaproteomic analyses revealed that hydrogen also may play an important role as an energy source in the O. algarvensis symbiosis, based on the abundant expression of periplasmic uptake [NiFeSe] hydrogenases in both δ-symbionts (δ1: SP088; δ4: SP089). These [NiFeSe] hydrogenases have high affinities for hydrogen (20), consistent with the low hydrogen concentrations reported for oligotrophic sediments (<10 nM) (21) and marine sediments in general (<60 nM) (22). Therefore we were surprised to measure unusually high concentrations of hydrogen, 438–2,147 nM, in the sediment pore waters at the O. algarvensis collection site (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). These high concentrations could be a result of biological H2 production by anaerobic CO oxidizers and are consistent with the elevated CO concentrations at the collection site. The hydrogen concentrations in the worms’ habitat are much higher than those needed by common hydrogen-oxidizing microorganisms for growth (23), indicating that the δ-symbionts could easily use the hydrogen present in the Elba sediment as an energy source.

The use of hydrogen as an energy source by chemoautotrophic sulfur-oxidizing symbionts was shown recently for deep-sea Bathymodiolus mussels from hydrothermal vents (24). Our study indicates that hydrogen also might play a role as an energy source in shallow-water chemosynthetic symbioses. As with CO, the use of externally supplied hydrogen might be another adaptation of the O. algarvensis symbiosis to life in the sulfide-depleted sediments of Elba.

Highly abundant uptake transporters for organic substrates in the δ-symbionts.

The sulfate-reducing δ-symbionts expressed extremely high numbers and quantities of high-affinity uptake transport-related proteins, which enable them to take up organic substrates at very low concentrations (Datasets S2 and S4). In the δ1-symbiont, 89–116 transport proteins were detected per sample, corresponding to an average of 29% of all identified δ1-symbiont proteins. In terms of abundance, the δ1-symbiont transport proteins amounted to more than 38% of the total δ1-symbiont protein (SI Appendix, Table S4). To our knowledge, higher abundances of these types of transporters have been found only in the metaproteome of the α-proteobacterium Pelagibacter ubique (SAR11) from the Sargasso Sea during extreme low-nutrient conditions (SI Appendix, Table S4) (25).

Most of the identified transport proteins in the δ1-symbionts were periplasmic-binding proteins of high-affinity ATP-binding cassette (ABC)- or tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic (TRAP)-type transporters, which actively transport substrates against a large concentration gradient while using energy in the form of ATP or an ion gradient (26, 27). The great majority of the detected δ1-symbiont transport proteins are used for the uptake of a variety of substrates such as amino acids, peptides, di- and tricarboxylates, sugars, polyamines, and phosphonates, with amino acid and peptide transporters being the most dominant ones (Dataset S4). The abundance of transport-related proteins in the δ-symbionts suggests that these symbionts use organic substrates not only as an energy source but also as a source for preformed building blocks, thus saving resources by not having to synthesize these metabolic precursors de novo.

The organic substrates used by the δ-symbionts could be supplied internally from within the worms or externally from the environment. Our metabolomic analyses of whole worms revealed considerable amounts of dicarboxylates and some amino acids (in the low millimolar range), making an internal source of the organic substrates possible (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 and Table S2). However, the relatively high concentrations of these substrates are not consistent with the expression of energy-consuming high-affinity transporters by the δ-symbionts. In cultured bacteria (28–30) as well as in environmental communities (25, 31), ABC/TRAP transporters are induced at low substrate concentrations, and less energy-consuming transporters are used under nutrient-rich conditions. Most likely the metabolites that we measured in homogenized worms are not easily accessible to the δ-symbionts in situ, because the metabolites are enclosed in host or symbiont cells.

To examine if organic substrates are supplied externally from the O. algarvensis environment, we analyzed sediment pore waters from the worm's collection site with GC-MS for the presence of a large range of di- and tricarboxylates, amino acids, and sugars. None of these metabolites was measurable with detection limits at about 10 nM (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). Such oligotrophic conditions are consistent with the high expression of ABC/TRAP transporters that have extremely high affinities for substrates at concentrations far below the detection limits of our method (32, 33). The worm's cuticle is permeable for small, negatively charged compounds as well as substrates up to 70 kDa (5); thus the δ-symbionts would have access to both small organic compounds such as di- and tricarboxylates and larger organic substrates such as sugars and polyamines from the environment. The expression of transporters for a very broad range of substrates would allow the δ-symbionts to respond quickly to and take up many different substrates that could be consistently present at low concentrations in their environment or that could fluctuate over time and space as the worm migrates through the sediment.

Regardless of whether the organic substrates come from the environment or internally from within the symbiosis, the high abundances of high-affinity uptake transporters in the δ-symbionts indicate that the symbionts experience nutrient limitation, forcing them to dedicate a major part of their resources to the acquisition of substrates. Despite their endosymbiotic location, the lifestyle of these bacteria thus appears to resemble most closely that of planktonic SAR11 bacteria from low-nutrient extremes in the Sargasso Sea (25).

Recycling and Waste Management.

Given the extremely low concentrations of nutrients in the O. algarvensis habitat, the conservation of substrates and energy should be highly advantageous for the symbiosis. Our metaproteomic and metabolomic analyses revealed several pathways that could enable the symbionts to recycle waste products of their hosts and conserve energy.

Proposed pathways for the recycling of host fermentative waste in multiple symbionts.

Cross-species identification of host proteins enabled us to gain insight into the metabolism of O. algarvensis. Our analyses revealed that, when living in deeper anoxic sediment layers, O. algarvensis expressed proteins for an anaerobic metabolism that produces large amounts of acetate, propionate, malate, and succinate as fermentative waste products (SI Appendix, SI Text and Fig. S6 and Dataset S2) (34, 35). Correspondingly, we detected considerable amounts (1–8 mM) of malate, succinate, and acetate in the worm metabolome (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 and Table S2). Aquatic invertebrates without symbionts must excrete these fermentative waste products to keep their internal pH stable, thereby losing large amounts of energy-rich organic compounds. In O. algarvensis, the ability of the sulfate-reducing δ-symbionts to use their host's fermentative waste as substrates recycles and preserves considerable amounts of energy and organic carbon within the symbiotic system (SI Appendix, SI Text).

The dominant γ1-symbiont, previously assumed to fix only carbon autotrophically, also may function heterotrophically by assimilating acetate, propionate, succinate, and malate, thus also contributing to host waste recycling. We detected abundantly expressed enzymes for an almost complete 3-hydroxypropionate bi-cycle (3-HPB) in the γ1-symbiont (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S3B and Dataset S2). The 3-HPB is used for autotrophic CO2 fixation in Chloroflexus aurantiacus, a filamentous anoxygenic phototroph (36), but parts of the 3-HPB pathway also can be used for the heterotrophic assimilation of acetate, propionate, succinate, and malate (37).

Fig. 3.

Modified version of the 3-HPB in the γ1-symbiont. Reactions not needed for the assimilation of propionate and acetate are shown in the gray box; reaction 1 also can play a role in fatty acid metabolism. (1) Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (2004223475); (2) malonyl-CoA reductase; (3) propionyl-CoA synthase; (4) propionyl-CoA carboxylase (2004223080); (5) methylmalonyl-CoA epimerase (RASTannot_91923); (6) methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (RASTannot_20798); (7) succinyl-CoA:(S)-malate-CoA transferase (RASTannot_529, RASTannot_48547); (8) succinate dehydrogenase (2004223104, 2004223105); (9) fumarate hydratase (2004223692); (10 a,b,c) (S)-malyl-CoA/β-methylmalyl-CoA/(S)-citramalyl-CoA (MMC) lyase (RASTannot_91504); (11) mesaconyl-C1-CoA hydratase (β-methylmalyl-CoA dehydratase) (2004222675); (12) mesaconyl-CoA C1-C4 CoA transferase (RASTannot_38616); (13) mesaconyl-C4-CoA hydratase [(S)-citramalyl-CoA dehydratase] (RASTannot_6738).

In retrospect, it is clear why the 3-HPB pathway was not discovered in the metagenomic analyses of the O. algarvensis symbionts: Many of its genes occurred on sequence fragments that could not be assigned to a specific symbiont and therefore were not included in the annotation analyses (9). Here, we used our proteomics-based binning method described above to assign abundantly expressed 3-HPB enzymes encoded on unassigned metagenomic fragments to the γ1-symbiont (SI Appendix, SI Text, Materials and Methods and Dataset S3). This method enabled us to identify nearly all enzymes required for the complete 3-HPB, with the exception of two diagnostic enzymes of the 3-HPB, malonyl-CoA reductase and propionyl-CoA synthase, that were missing in both the metagenome and the metaproteome (Fig. 3).

To understand better how the 3-HPB might function in the symbionts, we performed enzyme assays with extracts from whole worms and enriched γ1-symbionts. Activities of all 3-HPB enzymes were detected, except for the two diagnostic enzymes that also were absent from the metaproteome (SI Appendix, Table S5). We therefore propose a modified incomplete 3-HPB as shown in Fig. 3, which the γ1-symbiont could use to assimilate the host's fermentative waste products acetate, propionate, succinate, and malate. The abundant expression of the modified 3-HPB suggests that it plays an important role in the central carbon metabolism of the γ1-symbionts. The net fixation of CO2 is unlikely because of the absence of the two diagnostic enzymes and the low activities of the carboxylases involved in the 3-HPB (SI Appendix, Table S5). The pathway could also be linked to the synthesis and/or mobilization of the storage compound polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA). A putative PHA synthase (2004222379) and a phasin protein (PHA granule protein, 6frame_RASTannot_14528) are highly expressed in the γ1-symbiont metaproteome, showing the importance of PHA synthesis for this symbiont. Under anaerobic conditions, PHA synthesis not only would produce a valuable storage compound but also would relieve the symbiont of superfluous reducing equivalents.

Intriguingly, one of the closest free-living relatives of the γ1-symbiont, Allochromatium vinosum, whose genome was sequenced recently, does not possess the genes needed for the 3-HPB or its modified version (http://genome.jgi-psf.org/allvi/allvi.home.html). The absence of these genes suggests that the genes for the 3-HPB pathway were gained through lateral transfer. Certainly, there is a strong selective advantage for this pathway in the γ1-symbionts. The γ1-symbionts are present in almost all gutless oligochaete species and therefore are assumed to be the ancient primary symbionts that first established a mutualistic relationship with the oligochaetes (5). The ability to recycle organic host waste would have been a considerable advantage during the early stages of the symbiosis, before the establishment of associations with other bacteria such as the heterotrophic sulfate-reducing symbionts.

Uptake and recycling of nitrogenous compounds.

Because sources of nitrogen are extremely limited in the habitat of O. algarvensis (38), efficient strategies for dealing with nitrogen limitation have a selective advantage. Our metaproteomic and metabolomic analyses of the O. algarvensis association indicate two major strategies for dealing with nitrogen limitation: (i) the use of high-affinity systems for the uptake of nitrogenous compounds from the environment, and (ii) conservation of nitrogen within the symbiosis through recycling.

Environmental nitrogen is most likely assimilated by the symbionts using glutamine synthetases as well as high-affinity uptake transporters. The γ1-, γ3-, and δ1-symbionts abundantly expressed glutamine synthetases (Dataset S2). This enzyme assimilates ammonia into glutamine with high affinity at very low ammonia concentrations and is expressed in cultured organisms only under low-nitrogen conditions (39, 40). Uptake of organic compounds from the environment presumably is a further source of nitrogen, given the abundant expression of high-affinity amino acid- and peptide-uptake transporters in the δ1-symbiont that enable it to acquire nitrogen-containing substrates at extremely low concentrations.

The second proposed strategy of the O. algarvensis association for dealing with low nitrogen availability is the internal recycling of nitrogenous host osmolytes and waste products by the symbionts. In many invertebrates, these compounds are removed through excretory organs called “nephridia.” Gutless oligochaetes are the only known annelid worms without nephridia, and their absence suggests that their symbionts have taken over the role of waste and osmolyte management. Our metabolomic analyses revealed high concentrations of two nitrogenous osmolyte and waste compounds in O. algarvensis, glycine betaine and urea (SI Appendix, Table S2), with glycine betaine being the most abundant metabolite detected in NMR measurements (∼60 mM) (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Glycine betaine is a well-known osmolyte in all kingdoms of life (41) and most likely also serves this function in O. algarvensis. The relatively high amounts of urea in O. algarvensis are unusual, because this nitrogenous waste compound and osmolyte is not commonly found in aquatic animals (41). The O. algarvensis symbionts abundantly expressed proteins for glycine betaine and urea uptake and for the pathways required to use them as carbon and nitrogen sources (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, SI Text).

Energy Conservation with Proton-Translocating Pyrophosphatases.

We propose several pathways for energy conservation in the O. algarvensis symbiosis. Both the γ-symbionts and the δ1-symbiont expressed pyrophosphate-dependent enzymes that could conserve energy in as yet undescribed modifications of classical metabolic pathways. Our analyses of published genomes indicate that these pathways may be common in sulfate reducers and chemoautotrophic bacteria.

The key enzyme for the proposed energy conservation pathways is a membrane-bound proton-translocating pyrophosphatase (H+-PPase), which is abundantly expressed in both the γ- and the δ1-symbionts (SI Appendix, SI Text). H+-PPases are widespread in all three domains of life. Despite their pervasiveness, remarkably little is known about the metabolic pathways in which they are used (42). H+-PPases are proton pumps that use the hydrolysis of inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) instead of ATP to generate a proton-motive force through the translocation of protons across biological membranes (Fig. 4). They also can work reversibly as proton-translocating pyrophosphate synthases (H+-PPi synthase) and produce PPi using a proton-motive force (42).

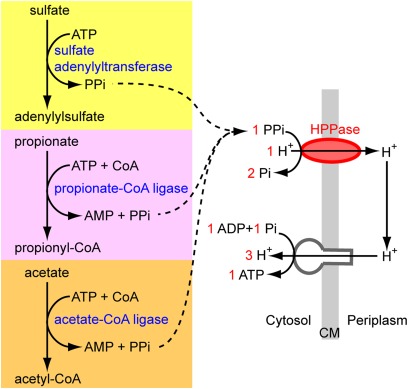

Fig. 4.

Suggested role of H+-PPase in the δ1-symbiont. Energy is conserved through the use of a membrane-bound proton-translocating pyrophosphatase instead of a cytosolic pyrophosphatase. PPi is produced by abundantly expressed enzymes, which catalyze the initial steps of sulfate reduction, propionate oxidation, and acetate oxidation. Red numbers show the stoichiometry.

H+-PPase energy conservation in sulfate reducers.

Sulfate-reducing bacteria produce large amounts of PPi as a by-product of the first step of sulfate reduction (Fig. 4). This PPi must be removed immediately to pull the reaction in the direction of sulfate reduction (43). For most sulfate reducers the mechanism of PPi removal is unknown. In some, it occurs through a wasteful hydrolysis of PPi by a soluble inorganic pyrophosphatase (44). In others, the energy from PPi hydrolysis may be conserved with an H+-PPase (45), but to date this process has not been proven. Our metaproteomic analyses support the conclusion that the sulfate-reducing δ1-symbiont uses the H+-PPase to conserve energy from PPi, based on the abundant expression of a H+-PPase and the absence of a soluble pyrophosphatase. The stoichiometry of the H+-PPase yields one ATP molecule per hydrolysis of three PPi molecules (46), providing the δ1-symbiont with a considerable energy gain of one additional ATP per three molecules of sulfate reduced.

Other sources of PPi besides sulfate reduction also appear to play an important role in the metabolism of the δ1-symbiont. In addition to expressing PPi-producing enzymes found in all organisms such as aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and RNA and DNA polymerases, the δ1-symbiont abundantly expressed at least two other PPi-producing enzymes: the acetate-CoA ligase (2004210485) and the propionate-CoA ligase (2004210481). Therefore, based on the abundant expression of numerous PPi-producing enzymes in the δ1-symbiont, we postulate that H+-PPase plays a key role in energy conservation in its metabolism (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S3A).

To examine how widespread H+-PPases are in sulfate reducers, we analyzed the genomes of sulfate reducers available in the databases. These analyses revealed H+-PPases in several sulfate reducers from two bacterial divisions, Desulfatibacillum alkenivorans AK-01 and Desulfococcus oleovorans Hxd3 from the Deltaproteobacteria, and Candidatus Desulforudis audaxviator MP104C and Desulfotomaculum reducens MI-1 from the division Clostridia. This finding suggests that the use of H+-PPases for energy conservation may be widely distributed among phylogenetically diverse sulfate-reducing bacteria.

Energy-efficient PPi-dependent pathways in sulfur oxidizers.

We propose that the γ-symbionts use novel energy-saving modifications of the Calvin cycle, glycolysis, and gluconeogenesis pathways. The key enzymes for the proposed modifications are the H+-PPase and a closely coupled PPi-dependent 6-phosphofructokinase (PPi-PFK). We show that these enzymes could save as much as 30% of the energy used by the ATP-dependent pathways and that this energy-saving pathway may be widespread in chemoautotrophic bacteria.

Metagenomic analyses of the O. algarvensis consortium showed that the γ1-symbiont lacks two key enzymes of the classical Calvin cycle, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase and sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase (the γ3-symbiont lacks only the latter) (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, the chemoautotrophic symbionts of the hydrothermal vent tubeworm Riftia pachyptila and the vesicomyid clams Calyptogena magnifica and Calyptogena okutanii also lack the genes for these two enzymes, even though all of them fix CO2 via the Calvin cycle (47–49). Newton et al. (48) hypothesized that a PPi-PFK might replace fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase for the C. magnifica symbiont, but no enzyme was found that could replace sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase. Therefore it remained unclear how the Calvin cycle could function in these chemoautotrophic symbionts.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the classical Calvin cycle with a proposed version that is more energy efficient. (A) The text book version of the Calvin cycle. (B) The more energy-efficient version of the Calvin cycle in the γ-symbionts through the use of PPi-dependent trifunctional 6-phosphofructokinase/sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase/phosphoribulokinase (green) and a proton-translocating pyrophosphatase/proton-translocating pyrophosphate synthase (H+-PPase/H+-PPi synthase) (red). The main differences between the cycles are highlighted in yellow. CM, cell membrane; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; GAP, d-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; PPi, inorganic pyrophosphate; Sh-7-P, d-sedoheptulose-7-phosphate. (C) Overview of genes that are replaced by the trifunctional PPi-dependent enzyme in different organisms. (D) Colocalized H+-PPase/PPi-PFK genes in the γ-symbionts and other symbiotic and free-living bacteria.

We found that both γ-symbionts of O. algarvensis possess a gene for a PPi-PFK that is highly similar to that of the methaneoxidizer Methylococcus capsulatus; amino acid identities were 71% for γ1 and 69% for γ3. The M. capsulatus PPi-PFK catalyzes three reactions: (i) the reversible, phosphate-dependent transformation of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate to fructose-6-phosphate and PPi; (ii) the reversible, phosphate-dependent transformation of sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphate to seduheptulose-7-phosphate and PPi; and (iii) the PPi-dependent phosphorylation of ribulose-5-phosphate to ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (50). Thus, PPi-PFK can replace the enzymes involved in these three reactions (fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase, sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase, and phosphoribulokinase) (Fig. 5 B and C and SI Appendix, SI Text). The PPi-PFK was abundantly expressed in the γ1-symbiont (the low coverage of the γ3-symbiont proteome might explain why it was not detected in this symbiont). We propose that in the O. algarvensis γ-symbionts, and possibly in other chemoautotrophs (see below), the PPi-PFK has multiple functions in the Calvin Cycle, glycolysis and gluconeogenesis, and that this leads to considerable energy savings as described below (Fig. 5 A and B).

In the classical Calvin cycle, the reactions catalyzed by fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase and sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase produce phosphate ions that cannot be used for energy gain. In contrast, if PPi-PFK replaces these enzymes, both reactions produce energy-rich pyrophosphates. Interestingly, in the genomes of both γ-symbionts, the genes for PPi-PFK are located in the immediate neighborhood of H+-PPases, indicating a close metabolic relationship between these two enzymes and their cotranscription (Fig. 5D), as shown for M. capsulatus, in which these genes also co-occur (Fig. 5D) (50). We propose that the pyrophosphate produced by the PPi-PFK in the Calvin cycle is used to conserve energy via the proton-motive force generated by the H+-PPase (Fig. 5B). This metabolic coupling between the PPi-PFK and H+-PPase would lead to energy savings of at least 9.25% (12/3 fewer molecules of ATP per six molecules of fixed CO2 in comparison with the classical Calvin cycle, in which 18 molecules of ATP are used for the fixation of six molecules of CO2). An even higher energy gain (31.5%) is possible if PPi-PFK also replaces ATP-dependent phosphoribulokinase in the last step of the Calvin cycle: The conversion of ribulose-5-phosphate to ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate could be energized with PPi from the two other Calvin-cycle reactions and/or the H+-PPase working in PPi synthesis direction, so that a total of 52/3 molecules of ATP (31.5%) would be saved per six molecules of CO2 fixed.

In addition to their proposed role in the Calvin cycle, we hypothesize that the PPi-PFK and H+-PPase also provide considerable energy savings in glycolysis and gluconeogenesis through several additional enzymes (SI Appendix, SI Text). Thus we conclude that PPi-PFK and H+-PPase might play a key role in energy conservation in the γ1-symbiont and most likely also in the γ3-symbiont.

Widespread occurrence of colocalized H+-PPase/PPi-PFK genes in chemoautotrophic bacteria.

To examine if other microorganisms also could use the PPi-PFK and H+-PPase for the pathways we propose above, we analyzed all bacterial (1,354) and archaeal (58) genomes available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information genomic database on January 29, 2009 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sutils/genom_table.cgi). We discovered colocalized H+-PPase/PPi-PFK genes, indicating close metabolic coupling and cotranscription, in the chemoautotrophic sulfur-oxidizing symbionts of C. magnifica and C. okutanii as well as in eight free-living bacterial species (Gamma- and Betaproteobacteria and Thermotogae), all of which possess ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase genes for autotrophic CO2 fixation (Fig. 5D). This broad distribution of colocalized H+-PPase/PPi-PFK genes in bacteria for which genomes are available suggests that H+-PPase/PPi-PFK–dependent pathways for energy conservation are widespread in both symbiotic and free-living chemoautotrophic bacteria.

The discovery of these pathways in chemoautotrophic bacteria is particularly interesting in light of evidence that H+-PPases may have an ancient origin (42). H+-PPase is the simplest known primary proton pump. It is the only known alternative to ATP synthases for the production of energy-rich phosphoanhydride bonds and is the only primary pump that is preserved in all three domains of life (42, 51). Given mounting evidence that the earliest forms of life were chemoautotrophic (52), the apparent pervasiveness of energy-conserving H+-PPase pathways in chemoautotrophs adds further weight to the hypothesis that PPi preceded ATP as the central energy carrier in the early evolution of life (51, 53, 54).

Conclusions

Our metaproteomic and metabolomic analyses of the O. algarvensis symbiosis provide strong indirect evidence for a number of unexpected and some as yet undescribed metabolic pathways and strategies that were not identified in the metagenomic analysis of the symbiotic consortium (9). We gained further functional insights by using proteomics-based binning. This method allowed us to include an additional 9 Mb of sequences in our analyses that could not be mined for genomic information by Woyke et al. (9) because their lengths were too short to enable a clear assignment to a specific symbiont.

One of the key questions in the metagenomic analyses of complex symbiotic consortia, including those of the human gut, is why there is so much functional redundancy (55, 56). The selective advantage for O. algarvensis of harboring two sulfur-oxidizing γ-symbionts with apparent functional redundancy was not clear. Our study shows that the only physiological traits shared by these two symbionts are their common use of reduced sulfur and carbon fixation via the Calvin cycle. Otherwise, they show very marked differences in their use of additional energy and carbon sources as well as electron acceptors. The γ3-symbionts may use CO and the host-derived osmolyte glycine betaine as additional energy and carbon sources, whereas the γ1-symbionts may use fermentative waste products from their hosts as additional carbon sources. Furthermore, the γ1-symbionts appear to rely heavily on storage compounds such as sulfur and polyhydroxyalkanoates, but storage compounds do not appear to play a dominant role in the metabolism of the γ3-symbionts. Resource partitioning also is visible in the differences in the electron acceptors used by the two symbionts. The γ1-symbionts may depend predominantly on oxygen for their respiration, but the γ3-symbionts apparently are not able to use this electron acceptor and instead use the energetically less favorable nitrate (SI Appendix, SI Text). Our metaproteomic analyses thus indicate functional differences in key metabolic pathways for chemosynthesis in the metabolism of these two symbionts, despite their genetic similarities. This theme appears to be a common one in microbial communities, because several recent proteomic and metaproteomic studies have shown that ecological differences between microorganisms with similar genomes are the result of major differences in their protein expression (57–59).

Although resource partitioning provides the association versatility and the ability to harvest a wide spectrum of energy and carbon sources, in one key aspect all four symbionts appear to share a remarkably similar metabolic strategy. They all express proteins involved in highly efficient pathways for the uptake, recycling, and conservation of energy and carbon sources. These pathways include (i) multiple strategies for the recycling of host waste products; (ii) the possible use of inorganic energy sources, such as hydrogen and CO, in addition to reduced sulfur compounds; (iii) the extremely abundant expression of high-affinity uptake transporters that would allow the uptake of a wide range of substrates at very low concentrations; and (iv) as yet undescribed energy-efficient steps in the pathways for sulfate reduction and CO2 fixation. Given the oligotrophic, nutrient-poor nature of the worm's environment in which organic compounds were below detection limits and reduced sulfur compounds were barely detectable, the selective pressure for metabolic pathways that maximize energy and carbon acquisition and conservation appears to have been very strong in shaping these symbioses.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection and Symbiont Enrichment.

Worms were removed from the sediment via decantation and were frozen immediately, or symbionts were enriched via isopycnic centrifugation using a HistoDenz-based (Sigma) density gradient before freezing (SI Appendix, SI Text). Symbiont abundance and composition in density-gradient fractions were analyzed with catalyzed reporter deposition-FISH using symbiont-specific probes (SI Appendix, SI Text, Fig. S1, and Table S6). Density-gradient fractions in which specific symbionts were enriched were chosen for subsequent analyses.

Protein Identification and Proteome Analyses.

1D PAGE followed by liquid chromatography (1D-PAGE-LC) and 2D-LC were used for protein and peptide separation as described previously (60, 61), with slight modifications (SI Appendix, SI Text). MS spectra and MS/MS spectra were acquired with a hybrid linear ion trap-Orbitrap (Thermo Fischer Scientific) as described previously (60, 62), with minor modifications (SI Appendix, SI Text). All MS/MS spectra were searched against two protein sequence databases composed of the symbiont metagenomes and the genomes of related organisms using the SEQUEST algorithm (see SI Appendix, SI Text for details). For protein identification only peptides identified with high mass accuracy (maximum ± 10 ppm difference between calculated and observed mass) were considered, and at least two different peptides were required to identify a protein. False-discovery rates were estimated with searches against a target-decoy database, as described previously (63, 64), and were determined to be between 0–3.27% (SI Appendix, SI Text and Table S7). For relative quantitation of proteins, normalized spectral abundance factor values were calculated for each sample according to the method of Florens et al. (65). All identified proteins and their relative abundance in different samples are shown in Datasets S1 and S2. Protein databases, peptide and protein identifications, and all MS/MS spectra are available from http://compbio.ornl.gov/olavius_algarvensis_symbiont_metaproteome/.

Proteomics-Based Binning.

Proteins encoded on metagenome fragments that were not assigned previously to a specific symbiont were assigned tentatively (binned) to a specific symbiont if they were detected repeatedly in higher abundances in enrichments of only one specific symbiont (SI Appendix, SI Text and Dataset S3). To validate this approach and to calculate a false-assignment rate, we also did proteomics binning with the proteins that already had been assigned to a specific symbiont in the metagenomic study (SI Appendix, SI Text and Table S3).

Enzyme Tests.

Enzymatic activities were determined in cell extracts from whole worms or from enriched symbionts (SI Appendix, SI Text and Table S5). Detailed methods for all enzyme activity assays are provided in the SI Appendix, SI Text.

Measurement of Hydrogen and CO Concentrations in the O. algarvensis Habitat.

Seawater and pore water samples from a sediment depth of 25 cm were collected by research divers using a stainless steel needle and capped syringes. A total of nine sites within an area of ∼100 m2 at the O. algarvensis collection site were sampled. Hydrogen and CO concentrations were measured the same day using an RGA3 reduction gas analyzer (Trace Analytical Inc.) (SI Appendix, SI Text).

Metabolite Identification and Quantification in Whole Worms and Pore Water.

Whole worms were extracted using ice-cold ethanol-based solvent mixture and ultrasonication. Metabolites were measured with GC-MS, LC-MS, and 1H-NMR as described previously (66), with minor modifications (SI Appendix, SI Text). Detected metabolites are shown in SI Appendix, Table S2. Relative quantification of metabolites was performed on the basis of complete spectrum/chromatogram intensities (SI Appendix, SI Text).

Pore water was sampled at different sediment depths in the O. algarvensis habitat by scuba divers with Rhizon MOM 10-cm soil water samplers (Rhizosphere Research Products, Wageningen, The Netherlands) and was measured using GC-MS as described in Liebeke et al. (66).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Tanja Woyke and Friedrich Widdel for stimulating scientific discussions, Thomas Holler and Harald Gruber-Vodicka for helpful comments on the manuscript, and many members of the working groups of Michael Hecker and Thomas Schweder for technical assistance. We also thank Daniel Kockelkorn for providing enzymes for 3-HPB–related enzyme assays, Bernd Giese for help with confocal laser-scanning microscopy, Ivaylo Kostadinov and Jost Waldmann for help with creating protein identification databases, Ann Hedley for providing the worm EST library sequences and support, and Martha Schattenhofer for assistance with automated cell counting. We thank the editor and reviewers of this paper, in particular Samantha B. Joye, for their insightful comments and feedback. M. Kleiner and C. Wentrup were supported by Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes scholarships. Funding for this study was provided by the Max Planck Society; by the Laboratory Directed Research and Development support at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, managed by UT-Battelle, LLC, for the US Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC05-00OR22725; and by Grant SCHW595/3-3 from the German Research Foundation (to T.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. C.R.F. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

See Author Summary on page 7148 (volume 109, number 19).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1121198109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Baumann P. Biology bacteriocyte-associated endosymbionts of plant sap-sucking insects. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2005;59:155–189. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felbeck H. Chemoautotrophic Potential of the Hydrothermal Vent Tube Worm, Riftia pachyptila Jones (Vestimentifera) Science. 1981;213:336–338. doi: 10.1126/science.213.4505.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cavanaugh CM, Gardiner SL, Jones ML, Jannasch HW, Waterbury JB. Prokaryotic Cells in the Hydrothermal Vent Tube Worm Riftia pachyptila Jones: Possible Chemoautotrophic Symbionts. Science. 1981;213:340–342. doi: 10.1126/science.213.4505.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dubilier N, Bergin C, Lott C. Symbiotic diversity in marine animals: The art of harnessing chemosynthesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:725–740. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubilier N, Blazejak A, Rühland C. In: Molecular Basis of Symbiosis, Symbiosis between bacteria and gutless marine oligochaetes, Progress in Molecular and Subcellular Biology. Overmann J, editor. Vol 41. Berlin: Springer; 2006. pp. 251–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubilier N, et al. Endosymbiotic sulphate-reducing and sulphide-oxidizing bacteria in an oligochaete worm. Nature. 2001;411:298–302. doi: 10.1038/35077067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giere O, Erséus C. Taxonomy and new bacterial symbioses of gutless marine Tubificidae (Annelida, Oligochaeta) from the Island of Elba (Italy) Org Divers Evol. 2002;2:289–297. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruehland C, et al. Multiple bacterial symbionts in two species of co-occurring gutless oligochaete worms from Mediterranean sea grass sediments. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:3404–3416. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woyke T, et al. Symbiosis insights through metagenomic analysis of a microbial consortium. Nature. 2006;443:950–955. doi: 10.1038/nature05192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleiner M, Woyke T, Ruehland C, Dubilier N. The Olavius algarvensis metagenome revisited: Lessons learned from the analysis of the low diversity microbial consortium of a gutless marine worm. In: Bruijn FJd., editor. Handbook of Molecular Microbial Ecology II: Metagenomics in Different Habitats. Vol 2. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2011. pp. 321–334. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warnecke F, Hugenholtz P. Building on basic metagenomics with complementary technologies. Genome Biol. 2007;8:231. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-12-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.King GM, Weber CF. Distribution, diversity and ecology of aerobic CO-oxidizing bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:107–118. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oelgeschläger E, Rother M. Carbon monoxide-dependent energy metabolism in anaerobic bacteria and archaea. Arch Microbiol. 2008;190:257–269. doi: 10.1007/s00203-008-0382-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conrad R, Meyer O, Seiler W. Role of carboxydobacteria in consumption of atmospheric carbon monoxide by soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981;42:211–215. doi: 10.1128/aem.42.2.211-215.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moran MA, et al. Genome sequence of Silicibacter pomeroyi reveals adaptations to the marine environment. Nature. 2004;432:910–913. doi: 10.1038/nature03170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King GM. Microbial carbon monoxide consumption in salt marsh sediments. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2007;59:2–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moran JJ, House CH, Vrentas JM, Freeman KH. Methyl sulfide production by a novel carbon monoxide metabolism in Methanosarcina acetivorans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:540–542. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01750-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thauer RK, Stackebrandt E, Hamilton WA. In: Sulphate-Reducing Bacteria: Environmental and Engineered Systems, Energy Metabolism and Phylogenetic Diversity of Sulphate-Reducing Bacteria. Barton LL, Hamilton WA, editors. New York: Cambridge Univ Press; 2007. pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mörsdorf G, Frunzke K, Gadkari D, Meyer O. Microbial growth on carbon monoxide. Biodegradation. 1992;3:61–82. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caffrey SM, et al. Function of periplasmic hydrogenases in the sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:6159–6167. doi: 10.1128/JB.00747-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodwin S, Conrad R, Zeikus JG. Influence of pH on microbial hydrogen metabolism in diverse sedimentary ecosystems. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:590–593. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.2.590-593.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novelli PC, et al. Hydrogen and acetate cycling in two sulfate-reducing sediments: Buzzards Bay and Town Cove, Mass. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1988;52:2477–2486. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karadagli F, Rittmann BE. Thermodynamic and kinetic analysis of the H2 threshold for Methanobacterium bryantii M.o.H. Biodegradation. 2007;18:439–452. doi: 10.1007/s10532-006-9073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petersen JM, et al. Hydrogen is an energy source for hydrothermal vent symbioses. Nature. 2011;476:176–180. doi: 10.1038/nature10325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sowell SM, et al. Transport functions dominate the SAR11 metaproteome at low-nutrient extremes in the Sargasso Sea. ISME J. 2009;3:93–105. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rees DC, Johnson E, Lewinson O. ABC transporters: The power to change. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:218–227. doi: 10.1038/nrm2646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forward JA, Behrendt MC, Wyborn NR, Cross R, Kelly DJ. TRAP transporters: A new family of periplasmic solute transport systems encoded by the dctPQM genes of Rhodobacter capsulatus and by homologs in diverse gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5482–5493. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5482-5493.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wick LM, Quadroni M, Egli T. Short- and long-term changes in proteome composition and kinetic properties in a culture of Escherichia coli during transition from glucose-excess to glucose-limited growth conditions in continuous culture and vice versa. Environ Microbiol. 2001;3:588–599. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2001.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mauchline TH, et al. Mapping the Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021 solute-binding protein-dependent transportome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:17933–17938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606673103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferenci T. Regulation by nutrient limitation. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:208–213. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sowell SM, et al. Environmental proteomics of microbial plankton in a highly productive coastal upwelling system. ISME J. 2011;5:856–865. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly DJ, Thomas GH. The tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic (TRAP) transporters of bacteria and archaea. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2001;25:405–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ames GFL. Bacterial periplasmic transport systems: Structure, mechanism, and evolution. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:397–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.002145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grieshaber MK, Hardewig I, Kreutzer U, Pörtner H-O. Physiological and metabolic responses to hypoxia in invertebrates. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1994;125:43–147. doi: 10.1007/BFb0030909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Hellemond JJ, van der Klei A, van Weelden SW, Tielens AG. Hellemond JJv Biochemical and evolutionary aspects of anaerobically functioning mitochondria. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2003;358:205–213, discussion 213–215. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zarzycki J, Brecht V, Müller M, Fuchs G. Identifying the missing steps of the autotrophic 3-hydroxypropionate CO2 fixation cycle in Chloroflexus aurantiacus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:21317–21322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908356106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zarzycki J, Fuchs G. Coassimilation of organic substrates via the autotrophic 3-hydroxypropionate bi-cycle in Chloroflexus aurantiacus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:6181–6188. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00705-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nemecky SN-M. 2008. Benthic degradation rates in shallow subtidal carbonate and silicate sands. PhD thesis (Univ of Bremen, Bremen, Germany)

- 39.Hua Q, Yang C, Oshima T, Mori H, Shimizu K. Analysis of gene expression in Escherichia coli in response to changes of growth-limiting nutrient in chemostat cultures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:2354–2366. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.4.2354-2366.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Voigt B, et al. The glucose and nitrogen starvation response of Bacillus licheniformis. Proteomics. 2007;7:413–423. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yancey PH. Organic osmolytes as compatible, metabolic and counteracting cytoprotectants in high osmolarity and other stresses. J Exp Biol. 2005;208:2819–2830. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Serrano A, Pérez-Castiñeira JR, Baltscheffsky M, Baltscheffsky H. H+-PPases: Yesterday, today and tomorrow. IUBMB Life. 2007;59:76–83. doi: 10.1080/15216540701258132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu CL, Peck HD., Jr Comparative bioenergetics of sulfate reduction in Desulfovibrio and Desulfotomaculum spp. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:966–973. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.2.966-973.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu M-Y, Le Gall J. Purification and characterization of two proteins with inorganic pyrophosphatase activity from Desulfovibrio vulgaris: Rubrerythrin and a new, highly active, enzyme. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;171:313–318. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91394-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thebrath B, Dilling W, Cypionka H. Sulfate activation in Desulfotomaculum. Arch Microbiol. 1989;152:296–301. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schöcke L, Schink B. Membrane-bound proton-translocating pyrophosphatase of Syntrophus gentianae, a syntrophically benzoate-degrading fermenting bacterium. Eur J Biochem. 1998;256:589–594. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2560589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Robidart JC, et al. Metabolic versatility of the Riftia pachyptila endosymbiont revealed through metagenomics. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:727–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Newton ILG, et al. The Calyptogena magnifica chemoautotrophic symbiont genome. Science. 2007;315:998–1000. doi: 10.1126/science.1138438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuwahara H, et al. Reduced genome of the thioautotrophic intracellular symbiont in a deep-sea clam, Calyptogena okutanii. Curr Biol. 2007;17:881–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reshetnikov AS, et al. Characterization of the pyrophosphate-dependent 6-phosphofructokinase from Methylococcus capsulatus Bath. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;288:202–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baltscheffsky H. In: Origin and Evolution of Biological Energy Conversion, Energy Conversion Leading to the Origin and Early Evolution of Life: Did Inorganic Pyrophosphate Precede Adenosine Triphosphate? Baltscheffsky H, editor. New York: Wiley-VCH; 1996. pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Say RF, Fuchs G. Fructose 1,6-bisphosphate aldolase/phosphatase may be an ancestral gluconeogenic enzyme. Nature. 2010;464:1077–1081. doi: 10.1038/nature08884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baltscheffsky H. Inorganic pyrophosphate and the evolution of biological energy transformation. Acta Chem Scand. 1967;21:1973–1974. doi: 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.21-1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miller SL, Parris M. Synthesis of pyrophosphate under primitive earth conditions. Nature. 1964;204:1248–1250. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Turnbaugh PJ, et al. The human microbiome project. Nature. 2007;449:804–810. doi: 10.1038/nature06244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yin B, Crowley D, Sparovek G, De Melo WJ, Borneman J. Bacterial functional redundancy along a soil reclamation gradient. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:4361–4365. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.10.4361-4365.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Denef VJ, et al. Proteogenomic basis for ecological divergence of closely related bacteria in natural acidophilic microbial communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:2383–2390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907041107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilmes P, et al. Community proteogenomics highlights microbial strain-variant protein expression within activated sludge performing enhanced biological phosphorus removal. ISME J. 2008;2:853–864. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Konstantinidis KT, et al. Comparative systems biology across an evolutionary gradient within the Shewanella genus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15909–15914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Otto A, et al. Systems-wide temporal proteomic profiling in glucose-starved Bacillus subtilis. Nat Commun. 2010;1:137. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Washburn MP, Wolters D, Yates JR., 3rd Large-scale analysis of the yeast proteome by multidimensional protein identification technology. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:242–247. doi: 10.1038/85686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Verberkmoes NC, et al. Shotgun metaproteomics of the human distal gut microbiota. ISME J. 2009;3:179–189. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peng J, Elias JE, Thoreen CC, Licklider LJ, Gygi SP. Evaluation of multidimensional chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC/LC-MS/MS) for large-scale protein analysis: The yeast proteome. J Proteome Res. 2003;2:43–50. doi: 10.1021/pr025556v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Elias JE, Gygi SP. Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nat Methods. 2007;4:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Florens L, et al. Analyzing chromatin remodeling complexes using shotgun proteomics and normalized spectral abundance factors. Methods. 2006;40:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liebeke M, et al. A metabolomics and proteomics study of the adaptation of Staphylococcus aureus to glucose starvation. Mol Biosyst. 2011;7:1241–1253. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00315h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]