Enactment of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act in 2008 was the culmination of a decades-long effort to improve insurance coverage for mental health and addiction treatment. The law’s passage constituted a critical first step toward bringing care for people with mental health and addiction disorders including depression, anxiety, psychoses, and substance abuse and dependence into the mainstream of the U.S. medical care system by requiring parity in coverage (i.e., equivalent benefits for mental health and substance abuse, often referred to collectively as “behavioral health,” services and all other medical and surgical services). Now, the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has the potential to affect the financing and delivery of mental health and addiction care even more profoundly.

Key ACA provisions hold promise for improving long-standing access problems and system fragmentation that affect the well-being of people with mental health and addiction disorders. Expansions of Medicaid, the mandate for employers to offer insurance, the creation of health insurance exchanges with subsidies for low-income people, and other reforms are expected to result in coverage for at least 3.7 million currently uninsured people with severe mental illnesses and many more with less severe needs for mental health and addiction treatment.1 The ACA goes beyond the requirements of the federal parity law by mandating that both Medicaid benchmark plans — alternative plan options created under the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 — and plans operating through the state-based insurance exchanges cover behavioral health services as part of an essential benefits package.

Equally important are the ACA’s delivery-system reforms that could help to address long-standing system fragmentation. Lack of integration between primary care and specialty behavioral health care and poor coordination for patients with coexisting mental health and addiction disorders are endemic to our delivery system and are exacerbated by the prevailing payment methods. Lack of coordination comes at a high price. People with serious mental illnesses have higher rates of other illnesses and die earlier, on average, than the general population, largely from treatable conditions associated with modifiable risk factors such as smoking, obesity, substance use, and inadequate medical care.2 And mental health and addiction disorders often go untreated in primary care.

The ACA’s emphasis on integrated care models, including patient-centered medical homes and accountable care organizations (ACOs), holds promise for improving coordination and the quality of care. Common sense (and evidence) suggests that it’s essential to target integration efforts at the points where patients interact with the health care system. That means doing a better job of detecting and treating mental health and addiction disorders in the primary care sector — and of addressing the medical needs of people with severe mental illnesses in the specialty mental health sector. There is extensive evidence regarding ways of providing high-quality treatment for depression, anxiety, and substance abuse within primary care; long-term outcome studies have emphasized the critical roles of care management, specialty consultation, and decision support.3 Less evidence is available on improving care coordination for people with disabling mental health and addiction disorders who would probably be best served by a medical home within the specialty mental health sector, although some promising approaches are being developed in the Veterans Health Administration and elsewhere.4

The ACA includes numerous innovations aimed at improving integration within Medicaid. The law created a Medicaid “health home” option for people with multiple chronic conditions, including those with mental health and addiction disorders, which will pay for services that haven’t traditionally been reimbursable. Care management, health promotion, post-inpatient transition care, referral to social support services, and information technology (IT) to link services together will be reimbursed at a 90% federal matching rate for the first 2 years after a health home is established. The ACA authorized $50 million in fiscal year 2010 and additional funds through fiscal 2014 for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to provide “co-location grants” to integrate services for adults with mental illness and coexisting medical conditions within community-based behavioral health treatment settings. The law made improvements to the Medicaid 1915(i) option, expanding states’ ability to provide home- and community-based services (e.g., day treatment and psychosocial rehabilitation) to specific populations, including those with serious mental illnesses. Another initiative provides funding for improving the capacity of federally qualified health centers to provide behavioral health care.

Under private insurance, integrated delivery systems such as ACOs could better align financial incentives to support coordination. In theory, bundled-payment models can fund evidence-based mental health and addiction services that are not typically paid for under private insurance, such as chronic care management. Risk adjustment and risk sharing will be critical in setting bundled-payment rates for ACOs, to temper any incentives to avoid patients with mental health and addiction disorders, who typically have higher-than-average health care costs. To facilitate integration, a behavioral health perspective should be included in ACOs’ governance. Similarly, leadership in the development of well-vetted, standardized performance measures for rewarding the delivery of high-quality behavioral health care within ACOs will be essential.

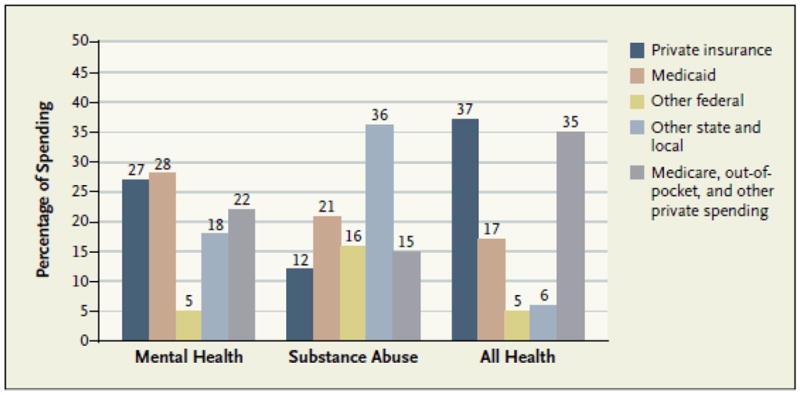

Although the ACA holds tremendous promise for improving access and reducing fragmentation for people with mental health and addiction disorders, numerous challenges remain. Some groups will not have access to behavioral health coverage even after the ACA is implemented; these include people in employer-sponsored plans that don’t offer behavioral health benefits and people who are ineligible for the coverage expansions (e.g., undocumented immigrants). Given the prospect of lower rates of uninsured people, states and the federal government will be tempted to reduce direct (non-Medicaid) financing of behavioral health services, particularly in light of cuts to discretionary spending that were negotiated as part of the recent debt-ceiling deal. These funds account for a much larger share of behavioral health spending than they do of overall health spending (e.g., 52% of substance abuse treatment vs. 11% of health care generally, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; see graph), and drastic cuts could threaten the viability of safety-net providers. It will be critical to preserve direct-service dollars to fund care for the remaining uninsured and for evidence-based services, such as assertive community treatment (a service delivery model involving 24-hour, individualized treatment, rehabilitation, and support services in the community) and supported employment, that aren’t typically reimbursed but can improve the well-being of people with more severe disorders.

The historical separation of mental health and addiction treatment from the rest of medicine also poses daunting challenges to integration. It’s not clear how health care reform will affect the widespread practice of “carving out” behavioral health benefits, which can mitigate health plans’ incentives to dissuade people with mental health and addiction disorders from enrolling but reinforces system fragmentation. Behavioral health care providers, who are disproportionately solo and small-group practitioners and have lagged behind other specialists in adopting information technology,5 will need to make changes to survive in this new environment, including developing IT capacities that facilitate integration and, in some cases, beginning to adopt third-party billing. The decision to exclude behavioral health care providers from the incentives in the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act of 2009 means that this transformation is getting a later-than-ideal start. Future IT investments in this sector will be critical.

After so many years of struggling to enact federal parity, some advocates had outsized expectations of what this policy could achieve. Yet the promise of parity was never to cure all the system’s ills. Parity’s real contribution was to increase financial protection, particularly for people with the most severe illnesses, by remving benefit limits that restricted access and increased economic vulnerability. Its passage was an important first step. The ACA — with its emphasis on expanding coverage and improving quality through better integration — constitutes a logical next step forward.

Percentages of U.S. Spending on Mental Health Care, Substance Abuse Services, and All Health Care That Were Covered by Various Types of Payers, 2005.

Data are from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Office of the Actuary.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Garfield RL, Zuvekas SH, Lave JR, Donohue JM. The impact of national health care reform on adults with severe mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;5(168):486–94. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10060792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and consequences of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2006;3(2) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: A cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2066;166:2314–21. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alakson V, Frank RG, Katz RE. Specialty care medical homes for people with severe, persistent mental disorders. Health Affairs. 2010;29(5):867–73. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mojtabai R. Use of information technology by psychiatrists and other medical providers. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(10):1261. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.10.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]