To the editor

In October 2011, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) released draft recommendations for prostate cancer screening.1 Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing was given a grade D, indicating that its use for routine screening should be discouraged. The draft recommendations contrast with those of the American Cancer Society and the American Urological Association.2,3 In the context of competing recommendations and clinical uncertainty, our goals were to examine primary care providers’ views of the draft recommendations and to determine to what extent they may be expected to change clinical practice.

Methods

A self-administered written survey was completed by practitioners in a university-affiliated practice, Johns Hopkins Community Physicians (JHCP). The JHCP is composed of 26 outpatient sites in 11 counties in Maryland. In 2010, approximately 40 000 men 40 years and older who were eligible for prostate cancer screening were seen at the JHCP. The survey was distributed at an annual organizational retreat. One hundred forty one physicians and nurse practitioners who deliver primary care for adult male patients attended the retreat and were eligible to participate. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland.

Results

The response rate was 88.7%. Of the participants, 62.1% were female and 37.9% were nonwhite. With regard to training, 48.8% of the participants were internal medicine physicians, 39.0% were family practitioners, and 12.2% were trained in internal medicine and pediatrics. Most of them (67.5%) had finished residency more than 10 years earlier.

One hundred fourteen of 123 providers (92.7%) had heard about the USPSTF draft recommendations (2 had missing data and were excluded), and they comprise the sample for the remainder of the analyses. Approximately half of them (49.2%) agreed or strongly agreed that the recommendations were appropriate, while 36.0% disagreed or strongly disagreed; the remainder neither agreed nor disagreed. In response to the question, “How do you think the draft recommendations will change your approach to routine PSA screening?” a few providers (1.8%) said that they would no longer order routine PSA testing; 21.9% said that they would be much less likely to do so; 38.6% said that they would be somewhat less likely to do so; and 37.7% said that they would not change their screening practices. In bivariate analyses, agreement with the recommendations and expectations as to how the participants would change practice did not vary significantly by provider training (agreement, P=.38; change practice, P=.91), years since residency graduation (agreement, P=.73; change practice, P=.36), sex (agreement, P=.48; change practice, P=.34), or race/ethnicity (agreement, P=.48; change practice, P=.33).

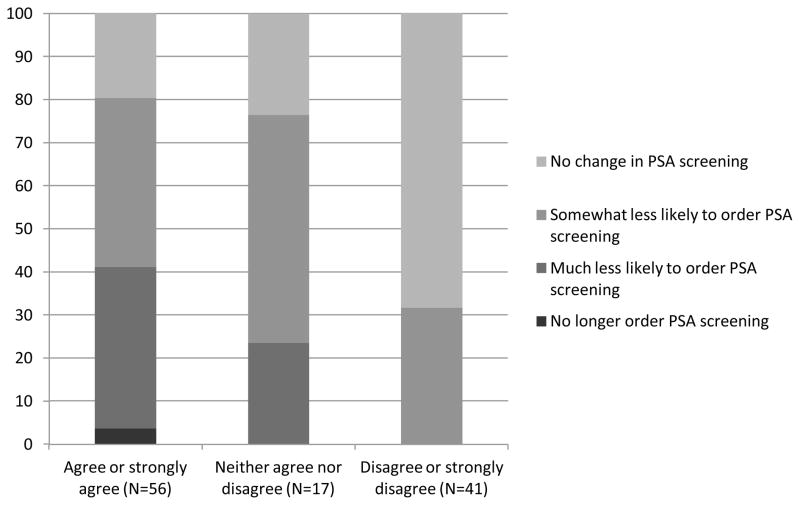

Providers who agreed with the draft recommendations were significantly more likely to state that the recommendations would change their clinical practice (Figure) (P.001). However, even among those clinicians who agreed with the draft recommendations, fewer than half (41.1%) stated that they would no longer order routine PSA screening or be much less likely to do so.

Figure 1.

Percent of providers who state that the USPSTF draft recommendations will change their prostate specific antigen (PSA) screening practice according to how strongly they agree or disagree with the draft recommendations. The sample included providers who had previously heard of the draft recommendations (N=114).

A total of 17.1% of providers said that over the past year they generally ordered PSA screening without discussing it with the patients, and 36.0% recommended PSA after discussing the benefits and harms with them. These clinicians were significantly less likely to state that the draft recommendations would cause them either to stop ordering PSA screening or to be much less likely to order PSA screening compared with clinicians who tended to let the patients decide on PSA screening after discussing the risks and benefits with them (11.9% vs 32.6%; P=.01).

Providers were asked about barriers to stopping routine PSA screening among patients who had previously received screening (not specific to the draft recommendations). The most frequently endorsed barriers were that patients expected them to continue screening (74.6% agreed or strongly agreed), lack of time to explain changes (66.7%), fear of malpractice litigation (54.0%), and discomfort with uncertainty (42.5%). Relatively fewer providers worried that older patients would think they were trying to cut costs (26.6%) or that patients would think the providers were “giving up” on them (18.7%).

Comment

Of this diverse sample of primary care providers, nearly half agreed with the USPSTF draft recommendations. Fewer providers believed that the recommendations would lead them to stop ordering PSA screening. The clinicians who were most likely to believe that the draft recommendations would change their practice patterns were the providers who were least likely to report routinely ordering PSA tests in the preceding year. The results suggest that, if finalized, the USPSTF recommendations may encounter significant barriers to adoption. To the extent that PSA screening should be reduced, it may be necessary to address patient perceptions’ about screening, to allow adequate time for screening discussions, and to reduce concerns regarding malpractice litigation.

This survey has several possible limitations, including incomplete response, reliance on self-report to determine PSA screening patterns, and generalizability to other patient care settings and patient populations. Self-reported screening behavior was similar to findings from other samples,4 and the overall rate of PSA testing in JHCP in 2010 (26.0% of patients >40 years of age) was the same as national screening rates.5 The study was conducted shortly after the release of the draft recommendations and provides an important baseline about physician attitudes toward the draft recommendations and PSA screening.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Elizabeth A. Platz ScD, MPH for her contributions to the study design, survey development, data interpretation, and manuscript revision. We also thank Erin Murphy and Sean Chen for their assistance with the survey. Ms. Murphy received financial compensation.

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: Maryland Cigarette Restitution Fund at Johns Hopkins provided funding. Dr. Pollack’s salary was supported by a career development award from the NIH National Cancer Institute and Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (1K07CA151910-01A1). Dr. Bhavsar’s salary was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant T32HS019488. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

References

- 1.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Prostate Cancer: Draft Recommendation Statement. [Accessed December 7, 2011];AHRQ Publication No. 12-05160-EF-2. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf12/prostate/draftrec3.htm.

- 2.Wolf AM, Wender RC, Etzioni RB, et al. American Cancer Society guideline for the early detection of prostate cancer: update 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:70–98. doi: 10.3322/caac.20066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greene KL, Albertsen PC, Babaian RJ, et al. Prostate specific antigen best practice statement: 2009 update. J Urol. 2009;182:2232–41. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.07.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linder SK, Hawley ST, Cooper CP, Scholl LE, Jibaja-Weiss M, Volk RJ. Primary care physicians’ reported use of pre-screening discussions for prostate cancer screening: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10 doi: 10.1186/1471=2296-10-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drazer MW, Huo D, Schoenberg MA, Razmaria A, Eggener SE. Population-Based Patterns and Predictors of Prostate-Specific Antigen Screening Among Older Men in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1736–43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.9004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]