Abstract

Children with medical complexity, regardless of underlying diagnoses, share similar functional and resource use consequences, including: intensive service needs, reliance on technology, polypharmacy, and/or home care or congregate care to maintain a basic quality of life, high health resource utilization, and, an elevated need for care coordination. The emerging field of complex care is focused on the holistic medical care of these children, which requires both broad general pediatrics skills and specific expertise in care coordination and communication with patients, families, and other medical and non-medical care providers. Many pediatric hospitalists have developed an interest in care coordination for CMC, and pediatric hospitalists are in an ideal location to embrace complex care. As a result of these factors, complex care has emerged as a field with many pediatric hospitalists at the helm, in arenas ranging from clinical care of these patients, research into their care, and education of future providers. The objective of this section of the review article is to outline the past, present, and possible future of children with medical complexity within several arenas in the field of pediatric hospital medicine, including practice management, clinical care, research, education, and quality improvement.

Children with Medical Complexity (CMC) Within Pediatric Hospital Medicine

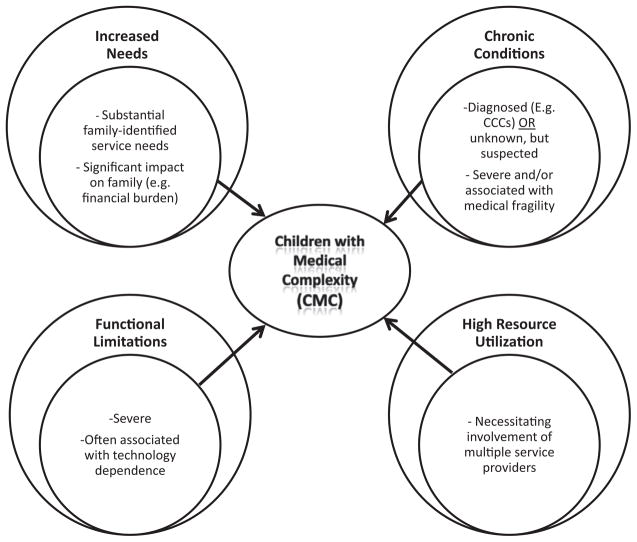

A recent definitional framework has been proposed that emphasizes 4 broad domains to characterize children with medical complexity (CMC): needs, chronic conditions, functional limitations, and health care use (Fig 1).1,2 Regardless of underlying diagnoses, all CMC share similar functional and resource use consequences, including intensive hospital- and/or community-based service need; reliance on technology, polypharmacy, and/or home care or congregate care to maintain a basic quality of life; risk of frequent and prolonged hospitalizations leading to high health resource utilization; and an elevated need for care coordination.3

FIG. 1.

Definitional framework for children with medical complexity. (Reproduced with permission from Pediatrics, Vol. 127, Pages 529–538, Copyright 2011 by the AAP.)

Historically, although the inpatient management of some groups of CMC was claimed by ambulatory subspecialists (such as pediatric pulmonologists directing the inpatient care of children with cystic fibrosis), the inpatient management of other groups of CMC has been left to a wide variety of subspecialists and/or general pediatricians. For instance, a child with neurologic impairment necessitating hospital admission could have their inpatient care directed by any number of services, such as neurology, rehabilitation, pulmonology, various surgical subspecialties, or by a general pediatrician.1 The emerging field of complex care is focused on the holistic medical care of these children. Provision of complex care requires both broad general pediatrics skills4 and specific expertise in care coordination and communication with patients, families, and other medical and nonmedical care providers.5 Recent trends in inpatient care have demonstrated an increasingly complex inpatient environment because of the growth in children with complex and/or chronic diagnoses admitted to hospital,6,7 the inexorable specialization within health care, resulting in new services and technologies,8 an increasing demand to provide efficient and cost-effective inpatient care, and challenges in ensuring the smooth transitions in care both within hospitals9 and between hospitals and the community.10 Not surprisingly, many pediatric hospitalists have started to develop an interest in care coordination for CMC.3 In addition, because more and more hospitalized children have chronic illnesses11 and are responsible for a substantial proportion of resource utilization, pediatric hospitalists are in an ideal position to embrace complex care.6,7,12–14 Because of these factors, complex care has emerged as a field with many pediatric hospitalists at the helm, in arenas ranging from clinical care of these patients, research into their care, and education of future providers.

The objective of this section of the review article is to outline the past, present, and possible future of CMC within several arenas in the field of pediatric hospital medicine, including practice management, clinical care, research, education, and quality improvement.

Practice Management

In the USA, health care reform will have a profound influence on the future scope of pediatric hospital medicine with regard to CMC. In contrast to past models that incentivized reduced utilization in discrete episodes of care, future models of care delivery will likely incentivize reduced overall utilization for a given patient across the cycle of care. At the time of the writing of this article, Medicaid programs in several states are developing accountable care organization-type arrangements, and many are focused on development of patient-centered medical home models for CMC. Emphasis in the future will clearly be on providing best care at lowest cost.

Existing care models usually provide enhanced care coordination and/or condition-specific expertise.1 Models include medical homes,15–18 comanagement, hospital-based19,20,21 and hybrid models, including disease-specific specialty clinics (eg, cystic fibrosis,22 epilepsy,23 and sickle cell disease.24) Adult providers are also developing adult complex care models.25 In addition to optimizing care models to bridge the gap between inpatient and outpatient settings,4 in the future, hospitalists and their outpatient/ambulatory partners must work to optimize transitions across other settings such as rehabilitation, transitional care, and home care organizations.

Implicit in these efforts to coordinate care between settings is a need to facilitate communication with families as well as communication between teams of providers both within and across care settings. The role of the electronic medical record and facilitating the transfer of health information across information technology platforms in these various settings is a critical focus for the present and near future.26

In this new era, continuity of care within a system will become critical to success; as a result, no matter how optimal hospital-based care is being provided, an increasing focus on improving the quality of care in other settings will be necessary. Therefore, a paradox exists, as optimizing care for these patients will mean expanding the purview of hospitalists beyond the walls of the hospital. During this period of uncertainty, it remains unclear where the traditional community– and primary care–based medical home will exist in the future for CMC. We may continue to see the continued growth of structured hospital-based comprehensive complex care programs,14 which numbered over 60 in a recent informal survey.12 Such hospital-based structured complex care programs have demonstrated reduction or shifts in costs.20,27–29 Although initial results suggest these clinics may improve outcomes for CMC,30,31 further research on care delivery for these children is needed beyond utilization, to including differences between models, as well as more comprehensive outcomes, such as child and family well-being. It is also unclear whether these clinics will be staffed by hospitalists as well as other disciplines (including midlevel providers), and whether these individuals will work in outpatient, inpatient, or both settings. Alternately, novel transitional care models may evolve. Adult hospitalist literature has described “subacute” models of care delivery for complex adult patients at high risk of readmission to the hospital, such as the frail elderly,32,33 as well work on optimizing discharge processes at the time of transition to home.34–36

Clinical Care

Currently, very limited evidence exists to inform the inpatient and outpatient care we provide to CMC; as a result, substantial variation exists in the management of even relatively common conditions. For example, despite it being one of the most common reasons for recurrent admission to a children’s hospital,13 there are few randomized controlled trials37 and no robust comparativeness effectiveness studies of different antimicrobial treatment for aspiration pneumonia. Although difficult to conduct and fund because of the varied underlying conditions of CMC, more clinical research focused on common clinical scenarios in these children is essential to improve the quality of the care we provide to them.

In addition to the need for high-quality evidence around the care we provide to CMC, it is important that we implement high-quality processes around decision making.38 This will hopefully empower patients and families to make decisions that are congruent with their personal values. For example, CMC and their families often face difficult decisions around assistive technology devices. Shared decision making is a conceptual model focused on the clinician–patient partnership in decision making around interventions.39 The dyads of doctor–patient share information about the treatment options and personal values around those options, then deliberate and decide together about what treatment to implement. Shared decision making is especially important in situations where there might be a lack of evidence, where there is no clear “best option,” or where the trade-offs between risks and benefits are very different—sometimes called preference-sensitive decisions. There is increasing appreciation that patient decision aids and tools that complement counseling, facilitate shared decision making, and improve patient decision quality are needed for the physician and the patient/family.40 This is particularly the case for decisions around technology, such as gastrostomy tube placement.41 Few patient decision aids exist for CMC. Such tools improve patient knowledge, improve realistic perceptions of chances of benefits and harm, reduce decisional conflict, result in greater engagement of patients in decision making, and improve the agreement between patients’ values and the option actually chosen.42 There will likely be extensive work in this area in the next 5 years.

For some interventions, especially those involving assistive technology devices, often multiple medical specialists and health care professionals (nursing, home care, occupational therapy/physical therapy) are involved in the decision-making process or are needed to support the family after the intervention has been implemented. There may be differing perspectives on the use of the technology amongst team members, which are often value based. To optimally support the family in hospital and at home, it is important that all relevant team members are engaged in the decision-making process and/or understand the goals of the intervention. Thus, we also anticipate expansion of shared decision making into physician/health care provider–physician models.

Finally, critical goals for all children with special health care needs include seamless health care transitions for adolescents and young adults to the adult medical care system.43–47 Providers in many children’s hospitals care for adults with childhood-onset diseases. As numbers of these adults increase, we need to evaluate whether other providers, such as dually trained medicine–pediatric specialists, are better trained to treat adults with childhood-onset diseases.47 In addition, pediatric hospitalists may potentially have a role in “consulting” to adult providers caring for young adults with complex chronic diseases of childhood.

Research

Definition the population of CMC is critical to furthering research into the evidence in their care in inpatient and outpatient settings.1 Ongoing research has characterized utilization for CMC. However, future research for CMC must incorporate both condition-specific and condition-independent outcomes.1 Some emerging literature focuses on condition-specific interventions and outcomes common to particular subgroups of CMC, such as comparative effectiveness of treatments for gastroesophageal reflux disease and antireflux procedures for children with neurologic impairment.48,49 Unfortunately, however, CMC are often excluded from condition-specific studies because of the rarity of underlying conditions, disease severity, and/or multiple comorbidities.50 As such, CMC also need more studies focused on condition-independent outcomes, such as measures of perceptions of health care quality or health-related quality of life, mental health,51 parental caregivers’ well-being and family circumstances,52–56 integration and participation in the community,57 and family knowledge about and use of their child’s medical care and community resources.1 Because the current challenges facing care providers for these children are extensive,58 we anticipate and hope that in the future, consideration of the needs and quality of life of CMC will routinely extend beyond the patient and to the family experience/perspective as well. Here, social science research methods, that is, qualitative research methods will be critical.59

Given the paucity of evidence in care provided to CMC, currently, we anticipate development of new knowledge in the next 5 years. Development of large data sets, such as Pediatric Health Information System + (PHIS+), will facilitate our ability to capitalize on existing variation in management with large comparative effectiveness studies.60 General pediatric research networks, including those focused on the inpatient setting, such as Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings,60 are necessary to amass suitable numbers of children for adequately powered studies, potentially even for randomized controlled trials. We hope that these developments in the near future will begin to improve our understanding of optimal care for CMC.

Education

Skills in managing CMC are necessary for all pediatric residents,61 but particularly future pediatric hospitalists. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies recognized this need62 and identified technology-dependent children, hospice and palliative care, and transitions of care in addition to specific medical issues for CMC. We anticipate that hospitalists will need an increased fund of knowledge in work traditionally within the scope of ambulatory providers, including, but not limited to, mobility and function (rehabilitation) and feeding (gastroenterology). The Academic Pediatric Association (APA) complex care group is developing a national curriculum to address the needs of complex care providers in the inpatient and outpatient settings (Listserve CC, personal communication, 2010). Finally, we anticipate an increasing focus on empowering families to develop care coordination skills.63

Quality Improvement

Improvement science addressing the care of CMC needs to link the clinical interventions being assessed with important and measurable outcomes. It is already known that CMC are especially vulnerable to safety issues, including medication errors in the inpatient setting,64 as well as medication reconciliation along the continuum of care. Examples of other such outcomes that should be measured in the near future include meeting family identified needs, reducing condition-specific health complications, addressing functional limitations, and reducing unnecessary health service use.1

In the USA, development of future pediatric quality measures to be used by Medicaid will prioritize inpatient care, specialty care, and health outcome measures,65 all of which will be distinctive among CMC. Ongoing work is focused on development of measures of care coordination for CMC.66

Conclusions

In the past and present, the evolving field of complex care has been intertwined with the evolving field of pediatric hospital medicine. As health care models change in response to government regulation and market forces, we anticipate that this 2-way relationship will continue to develop. Pediatric hospital medicine will continue to influence the care of CMC both within and outside the hospital’s walls, and in turn, caring for CMC and supporting their families through their frequent journeys in and out of the hospital will inform how we practice hospital medicine, recognizing that we are an integral part of these children’s health homes. Great advances are needed, and we hope that with a growing cadre of clinicians and academics focused on improving the lives of these children, exciting advances in clinical care and quality improvement, followed by education and research, in the coming years will lead to improvement in the quality of care we provide for these children.

Footnotes

Disclosure: “Ongoing support for investigators includes Award K23NS062900 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders And Stroke (NINDS) and Seattle Children’s Center for Clinical and Translational Research and CTSA Grant Number ULI RR025014 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for TDS; and the Child Health Corporation of America via the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Setting Network Executive Council for TDS and SM. None of the sponsors participated in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the NCRR or NIH.”

References

- 1.Cohen E, Kuo DZ, Agrawal R, et al. Children with medical complexity: An emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics. 2011;127:529–38. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Lee JH, Mokkink LB, Grootenhuis MA, Heymans HS, Offringa M. Definitions and measurement of chronic health conditions in childhood: A systematic review. JAMA. 2007;297:2741–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.24.2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Srivastava R, Stone BL, Murphy NA. Hospitalist care of the medically complex child. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52:1165–87. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wise PH. Integrity matters: Recapturing the relevance of general academic pediatrics. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11:123–7. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ovretveit J. Evidence: Does Clinical Coordination Improve Quality and Save Money? London: Health Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon TD, Berry J, Feudtner C, Stone BL, Sheng X, Bratton SL, et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126:647–55. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns KH, Casey PH, Lyle RE, Bird TM, Fussell JJ, Robbins JM. Increasing prevalence of medically complex children in US hospitals. Pediatrics. 2010;126:638–46. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connolly B, Mahant S. The pediatric hospitalist and interventional radiologist: A model for clinical care in pediatric interventional radiology. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:1733–8. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000240728.63147.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sectish TC, Starmer AJ, Landrigan CP, Spector ND. Establishing a multisite education and research project requires leadership, expertise, collaboration, and an important aim. Pediatrics. 2010;126:619–22. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelly A, Golnik A, Cady R. A medical home center: Specializing in the care of children with special health care needs of high intensity. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12:633–40. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0271-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wise PH. The transformation of child health in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23:9–25. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.5.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke RT, Alverson B. Impact of children with medically complex conditions. Pediatrics. 2010;126:789–90. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, Cohen E, Agrawal R, Feudtner C, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305:682–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berry JG, Agrawal R, Kuo DZ, Cohen E, Risko W, Hall M, et al. Characteristics of hospitalizations for patients who use a structured clinical care program for children with medical complexity. J Pediatr. 2011;159:284–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goss CH, Rubenfeld GD, Ramsey BW, Aitken ML. Clinical trial participants compared with nonparticipants in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:98–104. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200502-273OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moss RB, Milla C, Colombo J, Accurso F, Zeitlin PL, Clancy JP, et al. Repeated aerosolized AAV-CFTR for treatment of cystic fibrosis: A randomized placebo-controlled phase 2B trial. Hum Gene Ther. 2007;18:726–32. doi: 10.1089/hum.2007.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooley WC, McAllister JW. Building medical homes: Improvement strategies in primary care for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2004;113(Suppl 5):1499–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramsey BW. Outcome measures for development of new therapies in cystic fibrosis: Are we making progress and what are the next steps? Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:367–9. doi: 10.1513/pats.200703-038BR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ernst RK, D’Argenio DA, Ichikawa JK, Bangera MG, Selgrade S, Burns JL, et al. Genome mosaicism is conserved but not unique in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from the airways of young children with cystic fibrosis. Environ Microbiol. 2003;5:1341–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2003.00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon JB, Colby HH, Bartelt T, Jablonski D, Krauthoefer ML, Havens P. A tertiary care-primary care partnership model for medically complex and fragile children and youth with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:937–44. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.10.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gillette Y, Hansen NB, Robinson JL, Kirkpatrick K, Grywalski R. Hospital-based case management for medically fragile infants: Results of a randomized trial. Patient Educ Couns. 1990;17:59–70. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(91)90051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas CL, O’Rourke PK, Wainwright CE. Clinical outcomes of Queensland children with cystic fibrosis: A comparison between tertiary centre and outreach services. Med J Aust. 2008;188:135–9. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams J, Sharp GB, Griebel ML, Knabe MD, Spence GT, Weinberger N, et al. Outcome findings from a multidisciplinary clinic for children with epilepsy. Child Health Care. 1995;24:235–44. doi: 10.1207/s15326888chc2404_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rahimy MC, Gangbo A, Ahouignan G, Adjou R, Deguenon C, Goussanou S, et al. Effect of a comprehensive clinical care program on disease course in severely ill children with sickle cell anemia in a sub-Saharan African setting. Blood. 2003;102:834–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiss KB. Managing complexity in chronic care: An overview of the VA state-of-the-art (SOTA) conference. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(suppl 3):374–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0379-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berry JG, Goldmann DA, Mandl KD, Putney H, Helm D, O’Brien J, et al. Health information management and perceptions of the quality of care for children with tracheotomy: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:117. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casey PH, Lyle RE, Bird TM, Robbins JM, Kuo DZ, Brown C, et al. Effect of hospital-based comprehensive care clinic on health costs for Medicaid-insured medically complex children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:392–8. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berman S, Rannie M, Moore L, Elias E, Dryer LJ, Jones MD., Jr Utilization and costs for children who have special health care needs and are enrolled in a hospital-based comprehensive primary care clinic. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e637–42. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liptak GS, Burns CM, Davidson PW, McAnarney ER. Effects of providing comprehensive ambulatory services to children with chronic conditions. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:1003–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.10.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen E, Jovcevska V, Kuo DZ, Mahant S. Hospital-based comprehensive care programs for children with special health care needs: A systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:554–61. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agrawal R, Antonelli RC. Hospital-based programs for children with special health care needs: Implications for health care reform. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:570–2. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis G, Bardsley M, Vaithianathan R, Steventon A, Georghiou T, Billings J, et al. Do “virtual wards” reduce rates of unplanned hospital admissions, and at what cost? A research protocol using propensity matched controls. Int J Integr Care. 2011;11:e079. doi: 10.5334/ijic.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer H. A new care paradigm slashes hospital use and nursing home stays for the elderly and the physically and mentally disabled. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:412–5. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Misky GJ, Wald HL, Coleman EA. Post-hospitalization transitions: Examining the effects of timing of primary care provider follow-up. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:392–7. doi: 10.1002/jhm.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parry C, Min SJ, Chugh A, Chalmers S, Coleman EA. Further application of the care transitions intervention: Results of a randomized controlled trial conducted in a fee-for-service setting. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2009;28:84–99. doi: 10.1080/01621420903155924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1822–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jacobson SJ, Griffiths K, Diamond S, Winders P, Sgro M, Feldman W, et al. A randomized controlled trial of penicillin vs clindamycin for the treatment of aspiration pneumonia in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151:701–4. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170440063011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jackson C, Cheater FM, Reid I. A systematic review of decision support needs of parents making child health decisions. Health Expect. 2008;11:232–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2008.00496.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: Revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:651–61. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Connor AM, Wennberg JE, Legare F, Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Moulton BW, Sepucha KR, et al. Toward the “tipping point”: Decision aids and informed patient choice. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:716–25. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mahant S, Jovcevska V, Cohen E. Decision-making around gastrostomy-feeding in children with neurologic disabilities. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e1471–81. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Connor AM, Stacey D, Entwistle V, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Rovner D, Holmes-Rovner M, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;2:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine. A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1304–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reiss J, Gibson R. Health care transition: Destinations unknown. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1307–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parker HW. Transition and transfer of patients who have cystic fibrosis to adult care. Clin Chest Med. 2007;28:423–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reid GJ, Irvine MJ, McCrindle BW, Sananes R, Ritvo PG, Siu SC, et al. Prevalence and correlates of successful transfer from pediatric to adult health care among a cohort of young adults with complex congenital heart defects. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e197–205. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.3.e197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simon TD, Lamb S, Murphy NA, Hom B, Walker ML, Clark EB. Who will care for me next? Transitioning to adulthood with hydrocephalus. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1431–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wales PW, Diamond IR, Dutta S, Muraca S, Chait P, Connolly B, et al. Fundoplication and gastrostomy versus image-guided gastrojejunal tube for enteral feeding in neurologically impaired children with gastroesophageal reflux. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:407–12. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.30849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Srivastava R, Downey EC, O’Gorman M, Feola P, Samore M, Holubkov R, et al. Impact of fundoplication versus gastrojejunal feeding tubes on mortality and in preventing aspiration pneumonia in young children with neurologic impairment who have gastroesophageal reflux disease. Pediatrics. 2009;123:338–45. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cohen E, Zlotnik Shaul R. Beyond the therapeutic orphan: Children and clinical trials. Pediatr Health. 2008;2:151–9. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Witt WP, Kasper JD, Riley AW. Mental health services use among school-aged children with disabilities: The role of sociodemographics, functional limitations, family burdens, and care coordination. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:1441–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2003.00187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramsey BW. Appropriate compensation of pediatric research participants: Thoughts from an Institute of Medicine committee report. J Pediatr. 2006;149(Suppl 1):S15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brehaut JC, Kohen DE, Raina P, Walter SD, Russell DJ, Swinton M, et al. The health of primary caregivers of children with cerebral palsy: How does it compare with that of other Canadian caregivers? Pediatrics. 2004;114:e182–91. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.2.e182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thorne SE, Radford MJ, Armstrong EA. Long-term gastrostomy in children: Caregiver coping. Gastroenterol Nurs. 1997;20:46–53. doi: 10.1097/00001610-199703000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sabbeth BF, Leventhal JM. Marital adjustment to chronic childhood illness: A critique of the literature. Pediatrics. 1984;73:762–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ratliffe CE, Harrigan RC, Haley J, Tse A, Olson T. Stress in families with medically fragile children. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 2002;25:167–88. doi: 10.1080/01460860290042558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rosenbaum P, Stewart D. The World Health Organization International classification of functioning, disability, and health: A model to guide clinical thinking, practice and research in the field of cerebral palsy. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2004;11:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kuo D, Cohen E, Agrawal R, Berry J, Casey P. A national profile of caregiver challenges among more medically complex children with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:1–7. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krumholz HM. Real-world imperative of outcomes research. JAMA. 2011;306:754–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wasserman R, Serwint JR, Kuppermann N, Srivastava R, Dreyer B. The APA and the rise of pediatric generalist network research. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klitzner TS, Rabbitt LA, Chang RK. Benefits of care coordination for children with complex disease: A pilot medical home project in a resident teaching clinic. J Pediatr. 2010;156:1006–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stucky ER, Ottolini MC, Maniscalco J. Pediatric hospital medicine core competencies: Development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:339–43. doi: 10.1002/jhm.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bridge to Independence. Maternal and Child Health Bureau (Title V, Social Security Act) Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services; [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stone BL, Boehme S, Mundorff MB, Maloney CG, Srivastava R. Hospital admission medication reconciliation in medically complex children: An observational study. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:250–5. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.167528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dougherty D, Schiff J, Mangione-Smith R. The children’s health insurance program reauthorization Act quality measures initiatives: Moving forward to improve measurement, care, and child and adolescent outcomes. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(Suppl 3):S1–S10. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Antonelli RC, McAllister JW, Popp J. Making Care Coordination a Critical Component of the Pediatric Health System: A Multi-disciplinary Framework. The Commonwealth Fund; 2009. Available from: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Publications/Fund-Reports/2009/May/Making-Care-Coordination-a-Critical-Component-of-the-Pediatric-Health-System.aspx. [Google Scholar]