Summary

Although diminutive in size, bacteria possess highly diverse and spatially confined cellular structures. Two related alpha-proteobacteria, Sinorhizobium meliloti and Caulobacter crescentus, serve as models for investigating the genetic basis of morphologic variations. S. meliloti, a symbiont of leguminous plants, synthesizes multiple flagella and no prosthecae, whereas C. crescentus, a freshwater bacterium, has a single polar flagellum and stalk. The podJ gene, originally identified in C. crescentus for its role in polar organelle development, is split into two adjacent open reading frames, podJ1 and podJ2, in S. meliloti. Deletion of podJ1 interferes with flagellar motility, exopolysaccharide production, cell envelope integrity, cell division, and normal morphology, but not symbiosis. As in C. crescentus, the S. meliloti PodJ1 protein appears to act as a polarity beacon and localizes to the newer cell pole. Microarray analysis indicates that podJ1 affects the expression of at least 129 genes, the majority of which correspond to observed mutant phenotypes. Together, phenotypic characterization, microarray analysis, and suppressor identification suggest that PodJ1 controls a core set of conserved elements, including flagellar and pili genes, the signaling proteins PleC and DivK, and the transcriptional activator TacA, while alternate downstream targets have evolved to suit the distinct lifestyles of individual species.

Keywords: prokaryotic development, cell cycle, gene expression, bacterial genetics, signal transduction, fluorescence microscopy

Introduction

Bacterial cells are intricate, three-dimensional machines with defined, yet dynamic, subcellular components (Dworkin, 2009; Margolin, 2009). These components range from organelles, such as flagella and pili, to multimeric protein complexes, such as secretion channels and the cell division apparatus. Efficient assembly and disassembly of these macromolecular structures at appropriate times and locations ensure survival in capricious environments (Shapiro et al., 2002; Gitai, 2005; Ebersbach and Jacobs-Wagner, 2007). Furthermore, proper positioning of subcellular components plays an important role in interactions between bacteria and their eukaryotic hosts. For example, when Listeria, Shigella, and Rickettsia invade the cytoplasm of mammalian cells, unipolar nucleating factors promote the formation of actin tails that propel the bacteria for dissemination into neighboring cells (Gouin et al., 2005; Leung et al., 2008). Also, the secretion apparatuses of numerous pathogens that inject effector molecules into their respective target host cells localize to the bacterial cell pole (Judd et al., 2005; Jaumouillé et al., 2008; Senf et al., 2008; Carlsson et al., 2009). Although the significance of bacterial subcellular organization in microbe-host interaction is gaining attention, details of how genetic information and environmental inputs are spatially integrated during infection remain murky.

Sinorhizobium meliloti is an advantageous model for investigating the interface of subcellular architecture and microbe-host interactions. This endosymbiotic alpha-proteobacterium invades the roots of compatible legume hosts and elicits formation of specialized nodules, in which S. meliloti cells reside (Jones et al., 2007). Key steps of this mutualistic process have been elucidated, and numerous genetic and molecular tools exist to facilitate advances in understanding (Barnett and Fisher, 2006). Development of this symbiotic relationship requires intimate interaction and complex communication between the participants, as well as a relaxation of host defense mechanisms (Deakin and Broughton, 2009; Downie, 2010). Prior to nodule formation, chemical signals are exchanged: flavonoid compounds from the plant roots and Nod factor from the bacterium (Long, 2001). Following this exchange, S. meliloti cells that have adhered to root hairs invade via an infection thread into the root cortex, where they enter cells of the developing nodule and differentiate into bacteroids, capable of reducing dinitrogen into ammonium (Gage, 2004; Prell and Poole, 2006). The host plant assimilates the ammonium and, in return, feeds carbon compounds to the bacteroids. Besides the initial signals, bacterial cell surface components, such as extracellular polysaccharides, are required for effective and chronic infection (Jones et al., 2008). These polysaccharides include succinoglycan (also known as exopolysaccharide I, or EPS-I), galactoglucan (EPS-II), and cyclic beta-glucans (Dickstein et al., 1988; Glazebrook and Walker, 1989; Dylan et al., 1990; Pellock et al., 2000). In particular, succinoglycan is critical for the laboratory strain Rm1021 to form infection threads, as it does not produce symbiotically active EPS-II due to a disruption of the expR gene (Pellock et al., 2002; Marketon et al., 2003). In addition, flagellar motility appears to enhance the nodulation process (Ames and Bergman, 1981; Bauer and Caetano-Anollés, 1990; Caetano-Anollés et al., 1992; Malek, 1992).

S. meliloti shares many critical factors that regulate cellular differentiation and organelle development with Caulobacter crescentus, a free-living alpha-proteobacterium that has emerged as an attractive system for understanding molecular mechanisms that control subcellular organization (Thanbichler, 2009). C. crescentus undergoes defined morphological changes during every round of its cell cycle (Fig. 1A) (Collier and Shapiro, 2007; Curtis and Brun, 2010). Every division is asymmetric, producing a smaller, motile, swarmer cell and a larger, sessile, stalked cell. The stalked cell can initiate DNA replication and prepare for another round of division, whereas the swarmer cell must differentiate into a stalked cell before DNA replication can begin. The swarmer cell possesses a single flagellum at one cell pole and synthesizes Flp pili (Tomich et al., 2007) at this same pole. When the swarmer differentiates into a stalked cell, these organelles are replaced by the stalk, with an adhesive holdfast at its distal end. As the stalked cell elongates and prepares for division, a flagellum and the pilus secretion machinery are assembled at the pole opposite the stalk, such that two distinct progeny cells are produced after cytokinesis. Thus, polar organelles are assembled and disassembled in a temporally and spatially defined manner. Many of the regulatory circuits that control organelle development and cell polarity in C. crescentus have been elucidated in detail and shown to involve the interplay of factors with specific subcellular locations (Laub et al., 2007). Although S. meliloti and other alpha-proteobacteria appear morphologically quite distinct, critical genetic circuits identified in C. crescentus are typically conserved across the phylogenetic group (Wright et al., 1997; Barnett et al., 2001; Brilli et al., 2010; Schneiker-Bekel et al., 2011), and key proteins exhibit similar localization patterns (Lam et al., 2003; Hallez et al., 2007; Greif et al., 2010).

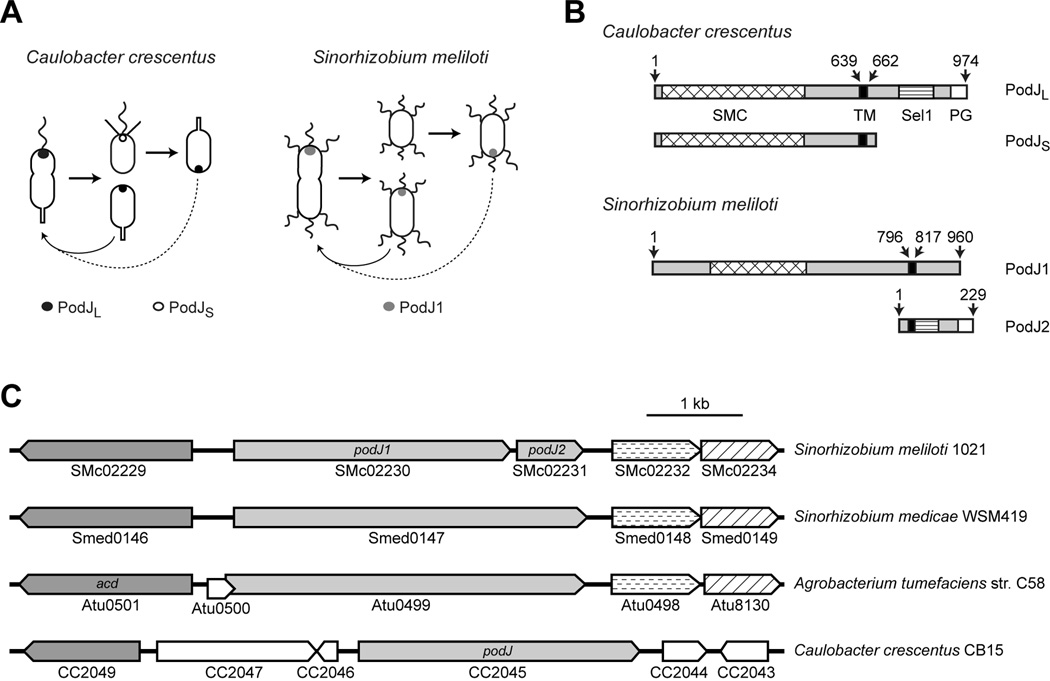

Fig. 1.

Comparison of PodJ orthologs. (A) Schematics depict similarity in PodJ localization in C. crescentus and S. meliloti. In C. crescentus, full-length PodJ (PodJL) localizes to the flagellated pole in the predivisional cell and segregates with the swarmer progeny, where its periplasmic domain is truncated to generate PodJS, the only PodJ isoform present in the swarmer cell; PodJS is then degraded before new PodJL is synthesized in the predivisional cell. Black circle denotes PodJL, whereas white circle denotes PodJS. Wavy line represents the single polar flagellum, straight lines represent pili, and straight rod represents the stalk. In S. meliloti, a PodJ ortholog (PodJ1) also localizes to the newer cell pole, the one generated by the most recent division. Gray dot denotes polarly localized PodJ1, and wavy lines represent multiple flagella. Dashed arrows indicate that the cell is rotated 180°, whereas solid arrows indicate that the orientation of the cell remains the same. (B) The S. meliloti genome contains two adjacent ORFs with similarity to different regions of C. crescentus podJ. S. meliloti PodJ1 (encoded by SMc02230) is similar to the N-terminal, cytoplasmic region of C. crescentus PodJ, while PodJ2 (encoded by SMc02231) is similar to the C-terminal, periplasmic region. C. crescentus PodJL contains both cytoplasmic and periplasmic domains, whereas the majority of PodJS resides in the cytoplasm. Cross-hatched box represents the SMC domain, black box indicates a transmembrane (TM) segment, box with horizontal bars the Sel1 domain, and white box the peptidoglycan (PG)-binding domain. Numbers indicate amino acids; for example, the predicted TM segment of PodJ1 is bounded by amino acids 796 and 817. The SMC, Sel1, and PG domains of PodJ span amino acids 19–466, 757–857, and 920–969, respectively; the SMC domain of PodJ1 spans residues 173–471, while the Sel1 and PG domains of PodJ2 span residues 47–122 and 171–217 (Marchler-Bauer et al., 2009). (C) The genomic region surrounding podJ is conserved in related alpha-proteobacteria (S. meliloti, S. medicae, A. tumefaciens, and C. crescentus). Gene and ORF names are shown as annotated, with pentagonal arrows indicating directionality. Light grey arrows indicate podJ orthologs (SMc02230, SMc02231, Smed0147, Atu0499, and CC2045). Dark grey arrows encode (putative) acyl-CoA dehydrogenases. Arrows with horizontal dashes encode proteins with permease domains, while arrows with diagonal lines represent conserved genes that encode putative TM proteins. The drawing is to scale; bar indicates 1 kb.

One key factor that contributes to the biogenesis of polar organelles in C. crescentus is the PodJ polarity determinant, which exists in two isoforms—PodJL and PodJS (Fig. 1B) (Viollier et al., 2002a; Hinz et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2006). These isoforms have distinct localization patterns that correspond to their functions (Fig. 1A). PodJL is the full-length protein, with a cytoplasmic N-terminal domain, a single transmembrane segment, and a periplasmic C-terminal region. Synthesized prior to cell division, it localizes to the pole opposite the stalk, where it recruits regulatory and structural proteins responsible for pili synthesis. After cell division, the periplasmic domain of PodJL is proteolytically removed to generate PodJS, which remains membrane-bound at the flagellated pole. PodJS is required for efficient motility in the swarmer and for holdfast formation as swarmer cells transition into stalked cells (Levi and Jenal, 2006; Hardy et al., 2010). During this transition, PodJS is degraded; then PodJL is newly synthesized and localized to the opposite pole. Because they are present at different times, the two PodJ isoforms appear to control distinct polar organelle functions. Results from genetic dissection support this idea, as the periplasmic domain of PodJL is required for pili production, while the cytoplasmic domain (of both PodJL and PodJS) is involved in flagellar motility and holdfast formation (Viollier et al., 2002a; Lawler et al., 2006).

One of the proteins recruited by PodJ to regulate organelle biogenesis is the PleC histidine kinase/phosphatase (Viollier et al., 2002a; Hinz et al., 2003; Lawler et al., 2006), which is part of a signal transduction system that detects completion of cytokinesis and promotes distinct cell fates in the two progeny cells (Matroule et al., 2004; Paul et al., 2008; Lin et al., 2010). Another component of the system is the DivJ histidine kinase, which sits at the stalked pole, opposite PleC in the predivisional cell (Wheeler and Shapiro, 1999). Acting in concert with the essential single-domain response regulator DivK in a spatially and temporally specific manner, PleC and DivJ regulate signaling cascades that implement asymmetric cell fates and drive cell cycle progression (Paul et al., 2008; Tsokos et al., 2011). Following cell division, the stalked progeny inherits only DivJ, which recruits DivK to the stalked pole and increases the level of phosphorylated DivK. Phosphorylated DivK in turn stimulates DivJ kinase activity, forming a positive feedback loop that signals other factors to execute a stalked cell-specific developmental program. In contrast, the swarmer cell inherits the flagellated pole and PodJ-recruited PleC, which dephosphorylates DivK and induces a swarmer cell-specific developmental program. As the swarmer cell matures into a stalked cell, the differentiating (flagellated to stalked) pole gains DivJ, which phosphorylates and recruits DivK. Phosphorylated DivK facilitates the swarmer-to-stalked transition, partly by switching PleC to an autokinase that activates the PleD diguanylate cyclase to produce cyclic di-GMP. Notably, PopA, a cyclic di-GMP effector protein that cooperates with PleD to coordinate cell cycle progression (Abel et al., 2011), also requires PodJ for localization to the newer, flagellated pole in predivisional cells (Duerig et al., 2009). Thus, PodJ plays a critical part in regulating these developmental programs: in the absence of PodJ, PleC fails to localize to the flagellated pole (Viollier et al., 2002a; Hinz et al., 2003), and presumably DivK activity is not modulated effectively. In support of this notion, a podJ mutant shows similar changes in gene expression as a pleC mutant, including reduced expression of flagellar and pili genes (Chen et al., 2006). Together with PodJ, the PleC-DivJ-DivK signal transduction system showcases how spatial positioning of key factors regulates organelle synthesis and morphological differentiation during defined periods of the cell cycle.

To shed light on the core pathways and principles that drive subcellular assembly and organization in alpha-proteobacteria, we examined the role of a PodJ homolog in S. meliloti strain Rm1021, asking how a polarity factor that negotiates organelle development in C. crescentus functions in a bacterium with obvious differences in morphology, including the absence of a stalk and holdfast and the presence of multiple flagella (Fig. 1A). We found that, despite the morphological differences, the PodJ homolog maintains a pattern of subcellular localization analogous to that in C. crescentus. It also retained control over select components of its regulatory network, including specific target genes that are conserved across species. Nevertheless, the configuration of the regulatory network has been altered to accommodate the particular physiology of S. meliloti, possibly ensuring coordination of developmental events in response to environmental conditions. Our results demonstrate that localized components execute critical functions in the core regulatory pathways of alpha-proteobacteria.

Results

Identification of podJ orthologs from sequenced genomes

To investigate the conservation of molecular mechanisms that mediate cell cycle progression and polarity in alpha-proteobacteria, we aimed to elucidate the role of PodJ in S. meliloti. We used BLAST (Johnson et al., 2008) to identify two adjacent ORFs in the sequenced S. meliloti Rm1021 genome (Galibert et al., 2001), SMc02230 and SMc02231, whose protein products showed strong similarity to different regions of C. crescentus PodJ (PodJCc). SMc02230, subsequently named podJ1, encodes a protein with similarity to the N-terminal, cytoplasmic domain of PodJCc (24% identity and 39% similarity, with 43% coverage, when compared to the first 639 amino acids of PodJCc). Like PodJCc, S. meliloti PodJ1 contains a transmembrane segment (Goudenège et al., 2010) and a cytoplasmic SMC domain, commonly found in proteins involved in the structural maintenance and segregation of bacterial chromosomes (Marchler-Bauer et al., 2009) (Fig. 1B). This SMC domain (residues 19–466 for PodJCc and 173–471 for PodJ1) includes coiled-coil motifs that were previously identified in PodJCc (Soppa, 2001; Lawler et al., 2006). SMc02231, or podJ2, encodes a protein with similarity to the C-terminal, periplasmic portion of full-length PodJCc (34% identity and 51% similarity, with 82% coverage, when compared to the last 312 amino acids of PodJCc). PodJ2 has a weak potential transmembrane helix at amino acids 32–51 (Claros and von Heijne, 1994) and, like PodJCc, contains a region of Sel1 repeats and a peptidoglycan-binding domain at its C-terminus (Marchler-Bauer et al., 2009) (Fig. 1B). A subtype of tetratricopeptide repeats (TPR), Sel1 repeats are predicted to mediate protein-protein interactions (Mittl and Schneider-Brachert, 2007).

When we initiated this study, the proximity of these two ORFs, each with similarity to a distinct region of C. crescentus PodJ, suggested that a genetic change split the ancestral podJ into two, but we were unsure of when the alteration occurred. As more alpha-proteobacterial genomes became available, we identified orthologs of podJ in all representative species in which there is strong conservation of the PleC-DivJ-DivK signaling pathway; this cluster includes Rhizobiales, Caulobacterales, and several Rhodobacterales (Brilli et al., 2010). Alignment with other podJ orthologs indicated that the genetic split is confined to S. meliloti. For example, S. meliloti, the closely related S. medicae, and Agrobacterium tumefaciens all share synteny in the region surrounding their respective podJ orthologs (Fig. 1C), but only S. meliloti has two adjacent ORFs with similarity to podJ. Moreover, sequence comparison among S. meliloti, S. medicae, and S. fredii suggested that a nonsense mutation (TAC to TAA) converted a Tyr to the stop codon of PodJ1 in S. meliloti (Fig. S1). This point mutation was found in the sequenced genomes of three SU47-derived S. meliloti laboratory strains: RCR2011 (Svetlana Yurgel and Mike Kahn, personal communication), Rm1021 (Galibert et al., 2001) (also re-sequenced by Svetlana Yurgel and Mike Kahn, personal communication), and Rm2011 (Delphine Capela, personal communication). However, podJ exists as a single ORF in three field isolates of S. meliloti: AK83, BL225C, and SM11 (Galardini et al., 2011; Schneiker-Bekel et al., 2011). Thus, the podJ1–podJ2 arrangement appears to be unique to S. meliloti SU47-derived strains. This relatively recent mutation, which probably arose during laboratory passage of the original SU47 strain, appears to have truncated the PodJ protein, because our experimental results (discussed below) suggest that the podJ2 gene is not expressed.

podJ1 mutation causes pleiotropic, cell envelope-associated defects

To begin determining the functions of podJ1 and podJ2 in S. meliloti Rm1021, we interrupted each gene by targeted insertion of an integrative plasmid. Flagellar motility of these mutants was then assessed on complex media (LB, TY, or PYE) containing 0.3% agar (Fig. 2A and data not shown). The podJ2 mutant did not exhibit any detectable defect, while the swarm formed by the podJ1 mutant was significantly smaller than that of the wild-type, but slightly larger than that of the exoS mutant, which has a well-characterized motility defect (Yao et al., 2004; Wells et al., 2007). Motile cells were observed when the podJ1 mutant, grown in liquid TY or PYE medium, was examined by phase contrast microscopy, albeit less frequently than in the wild-type culture. These results suggested that podJ1 regulates flagellar motility and/or chemotaxis in S. meliloti, as podJ does in C. crescentus.

Fig. 2.

Loss-of-function mutation in S. meliloti podJ1 results in poor flagellar motility, succinoglycan overproduction, and sensitivity to low osmolarity and mild detergent. (A) The swimming ability of wild-type Rm1021 and mutant strains was assessed after 3 days of incubation on PYE semisolid agar. Strain genotypes are as indicated. exoS, podJ1, and podJ2 mutants (Rm7096, JOE2420, and JOE2422) carry insertions in the corresponding genes. JOE2553 served as the ΔpodJ1 strain. Vector and plasmid used for the middle panel are pCM130 and pJC435, while vector and plasmid used for the right panel are pCM62 and pJC433. (B) Succinoglycan production was measured by examining the fluorescence of strains grown on LB solid medium containing 0.02% calcofluor. Five µL of a 10−3 dilution of each overnight culture (Rm1021, JOE2553, Rm7210, and Rm7096) was spotted onto the medium, incubated for three days, and imaged with UV light (see Experimental Procedures). Average fluorescence intensity was calculated from measurements of at least four independent plates. Error bars indicate standard deviations. (C) Ten-fold serial dilutions (10−2 to 10−6) of overnight cultures were spotted onto different solid media [LB, LBLS (LB low salt, with 0.1% NaCl), or LB with 0.1% or 0.05% deoxycholate], incubated for three or four days, and photographed. Strains used were Rm1021, JOE2553, VO2119, and R5D6.

Because reduced motility is often coupled with increased production of exopolysaccharides in S. meliloti (Barnett et al., 2004; Yao et al., 2004; Wells et al., 2007; Bahlawane et al., 2008), we assayed the brightness of colonies grown for three days on LB containing 0.02% calcofluor, which fluoresces under UV light when it binds to succinoglycan (Finan et al., 1985). As expected, we found that the podJ2 mutant was indistinguishable from wild-type, while the podJ1 mutant exhibited increased fluorescence (data not shown). To confirm our results seen with the podJ1 insertion mutant, we constructed two null alleles of podJ1, one an in-frame deletion (ΔpodJ1) and the other marked with an antibiotic resistance cassette (ΔpodJ1::Ω); strains carrying either allele behaved similarly in subsequent characterization. The fluorescence of the ΔpodJ1 strain on calcofluor plates was about twice (197%) that of the wild-type (Fig. 2B). For comparison, the relative fluorescence of two characterized mutants, exoY and exoS, with decreased or increased succinoglycan production, respectively (Doherty et al., 1988; Reuber and Walker, 1993; Yao et al., 2004), averaged 64% and 374% of wild-type (Fig. 2B). Although the phenotypic differences of the ΔpodJ1 strain were not as severe as those of the exoS mutant, the absence of PodJ1 clearly alters motility and exopolysaccharide production, both of which involve a large number of components in the cell envelope.

Cell envelope defects often lead to sensitivity to toxic agents and environmental stresses. For example, lpsB and bacA mutants, which have distinct alterations to the lipopolysaccharide of the outer membrane, have reduced tolerance for detergents (Campbell et al., 2003; Ferguson et al., 2004). We tested the ΔpodJ1 mutant on plates containing deoxycholate, a mild detergent, to see if it also exhibits this phenotype: the ΔpodJ1 mutant grew better than the lpsB but worse than the ΔbacA strain, and all three were more sensitive to deoxycholate than the wild-type (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, the ΔpodJ1 mutant grew poorly on LB plates with lower concentrations of sodium chloride (LBLS, for LB Low Salt) (Fig. 2C), suggesting adverse adaptation to low osmolarity. Intriguingly, this sensitivity to lower salt concentrations appears to be media-dependent, as the ΔpodJ1 mutant grew like wild-type on PYE (Fig. S2). After comparing the recipes for LB and PYE, we varied the concentrations of individual components in LB to determine the cause of sensitivity. The main culprit appears to be high levels of tryptone: changing the tryptone in LB to peptone or lowering its concentration from 1% to 0.2% alleviated the ΔpodJ1 mutant’s growth defect on complex media containing lower salt concentrations (Fig. S2). To test if this phenotype is dependent on growth rate, we compared colony formation at different temperatures. The sensitivity to LBLS persists at lower growth temperatures; moreover, at 20°C the mutant’s growth defect became evident even on LB (Fig. S3). We did not observe this atypical sensitivity to LBLS in other mutants with cell envelope defects, such as the lpsB and bacA strains (Fig. 2C). Therefore, PodJ1 appears to be involved in multiple aspects of cell envelope integrity in S. meliloti, a role not reported for PodJ in C. crescentus.

Next, we confirmed that the absence of podJ1 alone causes the pleiotropic defects associated with the cell envelope, first by generating additional strains with deletion of just podJ2 (ΔpodJ2) or both podJ1 and podJ2 (ΔpodJSm). In all assays, the ΔpodJ2 strain behaved as wild type, whereas the ΔpodJSm strain behaved as the ΔpodJ1 mutant (Fig. S4). Because we did not detect any obvious function for podJ2, we focused our attention on podJ1 and performed complementation analysis using the ΔpodJ1 mutant. We initially placed the podJ1 gene on a plasmid, under the control of a constitutive Escherichia coli lac promoter (Plac), and introduced it (pJC388) into the podJ1 deletion strain. Although this plasmid ameliorated the phenotypic defects, the mutant still formed slightly smaller swarms on motility plates and colonies on LBLS compared to wild type (data not shown). Knowing that podJ expression in C. crescentus is cell cycle-regulated (Crymes et al., 1999; Laub et al., 2000), we postulated that constitutive expression of podJ1 disrupted its cellular function in S. meliloti. Therefore, we created a complementing plasmid (pJC435) where podJ1 is expressed from its native promoter (PpodJ1) (see Experimental Procedures and Supplemental Information). As expected, this plasmid complemented the motility and cell envelope defects; whereas the vector alone, the vector carrying only the upstream fragment (PpodJ1), or the vector carrying only podJ1 after the transcriptional terminator, failed to complement the ΔpodJ1 mutation (Fig. 2A and Fig. S5). We obtained similar results with an egfp-podJ1 translational fusion allele (Fig. 2A and Fig. S5): while constitutive expression from Plac allowed partial complementation, expression of the fusion allele from PpodJ1 led to more complete rescue. In fact, constitutive expression of podJ1 or egfp-podJ1 was slightly deleterious in the wild-type, particularly in the presence of deoxycholate (Fig. S5 and data not shown). Thus, complementation analysis indicates that the observed motility and cell envelope phenotypes can be attributed to PodJ1, and appropriate expression of PodJ1 contributes to the regulation of its activities. Finally, we could not complement the ΔpodJ1 mutation with the C. crescentus podJ (podJCc) gene or, vice versa, the ΔpodJCc mutation with a plasmid carrying podJ1 or both podJ1 and podJ2 (Fig. S6), despite significant similarities that exist between the orthologs. The genes appear to have diverged sufficiently to prevent functional substitution.

In addition to the phenotypes discussed above, the podJ1 deletion mutant also exhibited cell division defects. When grown in the dilute complex media PYE, the mutant’s cell morphology appeared relatively normal (Fig. 3). In contrast, in LB complex media or M9 minimal media, the mutant formed chains and branched cells (Fig. 3), akin to the morphology previously observed when cell division or cell cycle progression was inhibited (Latch and Margolin, 1997; Cheng et al., 2007; Kobayashi et al., 2009). We used scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) to examine the cells in more detail (Fig. 4). Except for the branching morphology, ΔpodJ1 cells did not exhibit obvious perturbations on their surfaces. Also, flagella were rarely observed on wild-type or mutant cells grown in LB but easily detected in PYE, even on the occasional branched ΔpodJ1 cells. The flagella of ΔpodJ1 mutants were generally shorter and less abundant, consistent with their motility defect.

Fig. 3.

The ΔpodJ1 mutant exhibits aberrant cell morphology that is media-dependent and suggestive of cell division defects. Wild-type and ΔpodJ1 strains expressing FtsZ1-GFP (from pZ1RG2) were grown in the indicated media (PYE, LB, and M9 glucose) to log phase and examined by phase contrast (top row) and fluorescence (bottom row) microscopy. FtsZ1-GFP normally localizes to the mid-cell region, but its localization pattern is disrupted in the mutant, particularly in cells with branched morphology, seen in LB and M9. Scale bar inside the image indicates 5 µm.

Fig. 4.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) reveal morphology and flagella of wild-type and ΔpodJ1 cells grown in LB or PYE to log phase. Both wild-type and ΔpodJ1 cells produce flagella in PYE but rarely in LB. The flagella of ΔpodJ1 cells tended to be shorter and less abundant. Arrows point to where flagella protrude from cells in the SEM images. Scale bars indicate 1 µm.

To assess where the blockage occurs during cell division, we introduced into the strains a plasmid expressing a fusion of green fluorescent protein (GFP) to the cell division protein FtsZ1 (Ma et al., 1997), homologs of which have been shown to localize to the septum early during division (Adams and Errington, 2009). (S. meliloti contains two FtsZ paralogs, and FtsZ1 is more similar to those found in other species, while FtsZ2 appears to be dispensable for viability (Margolin and Long, 1994).) As seen previously (Ma et al., 1997), FtsZ1-GFP localized to the mid-cell division site in wild-type cells, forming Z-rings, regardless of the media used for growth (Fig. 3). FtsZ1-GFP also localized normally in ΔpodJ1 cells grown in PYE, but its localization pattern was irregular in LB and M9 (Fig. 3). In both of these less permissive media, Z-rings were still observed in a subset of cells, particularly in shorter filaments and those with more normal morphology. However, in longer filaments and branches, Z-rings were often absent or less abundant. These results suggest that when PodJ1 is absent, FtsZ1 localizes properly and division initiates, but later stages of cell division may be inhibited in a media-dependent manner due to cell envelope defects or cell cycle disruptions.

podJ1 deletion does not inhibit symbiosis

Considering that many of the defects found in the ΔpodJ1 mutant have been associated with ineffective symbiosis (Gibson et al., 2006; Wells et al., 2007; Griffitts et al., 2008), we examined the mutant’s ability to form nitrogen-fixing nodules on Medicago sativa (alfalfa). Surprisingly, we did not observe any deficiency in symbiosis. Plants inoculated with the ΔpodJ1 mutant formed healthy, pink nodules and were indistinguishable from those inoculated with wild-type Rm1021. Similarly, mutants with deletion of podJ2 or both podJ1 and podJ2 (ΔpodJSm) demonstrated normal symbiosis with alfalfa. We also investigated whether the ΔpodJ1 mutant can compete effectively against wild-type cells when the two are mixed in equal ratios for co-infection. At first, we grew the strains in LB and diluted the cultures in ½X BNM media for inoculation, and examination of isolates from the infected plants suggested that a majority of the nodules (63%) were occupied predominantly by wild-type cells. However, we subsequently determined that the mutant had decreased viability compared to wild type when grown in LB and resuspended in ½X BNM, most likely due to its cell envelope defects. So we repeated the nodulation competition experiment by growing the strains in PYE and resuspending the cells in water, after confirming that such treatment did not adversely affect the mutant’s viability. We inoculated 20 plants with a mixture of wild-type and ΔpodJ1::Ω cells, and another 20 with a mixture of marked wild-type and unmarked ΔpodJ1 mutant. Two nodules were removed from each plant, and their bacterial contents determined. Both sets of plants yielded similar results: 55 or 56% of the tested nodules contained predominantly mutant bacteria. Thus, the podJ1 null mutant competed effectively against the wild type for infection and nodulation. This lack of symbiotic deficiency may be because the physiological defects of the podJ1 mutant are milder or less significant during nodulation than those found in other mutants.

PodJ1 localizes to the newer cell pole

In C. crescentus, PodJ serves as a polarity determinant that recruits other proteins involved in organelle development and cellular differentiation to one pole of the cell (Fig. 1A) (Viollier et al., 2002a; Hinz et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2006; Lawler et al., 2006; Duerig et al., 2009; Hardy et al., 2010). To see if PodJ1 also acts as a polarity factor in S. meliloti, we examined its subcellular localization using an egfp-podJ1 fusion allele, expressed from podJ1’s own promoter on a low-copy-number plasmid (shown above to complement the podJ1 null mutation). Fluorescent foci were observed at one cell pole in both wild-type and ΔpodJ1 mutant cells expressing the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-PodJ1 fusion protein (Fig. 5A). Approximately 15% or 10% of the population exhibited this polar localization pattern for cultures grown in PYE or M9, respectively (n = 1728 or 1105 cells). A small subset of the cells expressing EGFP alone showed polar localization (3% in PYE, 2% in M9; n = 1143 or 659, respectively), but these foci were generally dimmer than those observed in cells expressing EGFP-PodJ1 (Fig. 5A). Therefore, these results suggest that PodJ1 localizes to one pole of the S. meliloti cell.

Fig. 5.

PodJ1 localizes to the newer cell pole, as revealed by time-lapse fluorescence microscopy. (A) Live cells expressing EGFP-PodJ1 (from pJC433) or EGFP alone (from pJC395) were examined by fluorescence and phase contrast microscopy. EGFP-PodJ1 localizes to one cell pole in a subset of the population and appears as fluorescent foci (indicated with arrows). Foci of similar brightness were rarely observed in cells expressing EGFP alone. (B) Images of cells expressing EGFP-PodJ1 were captured every 40 minutes to determine the dynamic pattern of localization. The top half of each row shows the fluorescence images, while the bottom half shows the corresponding phase contrast images, overlaid with schematics of the cell outline (in red) and PodJ1 localization (as green dots). Numbers indicate minutes elapsed. White scale bars indicate 2 µm. This set of images (taken with strain JOE2553 / pJC433) is representative of the same temporal pattern seen in five independent cells.

To confirm the polar localization of PodJ1, we integrated into the chromosome a suicide plasmid with mCherry translationally fused to the 3’ region of podJ1, such that the resulting strain expressed PodJ1-mCherry as the only full-length form of PodJ1 from the native locus. The strain behaved as wild type in physiological assays and exhibited polar localization of PodJ1-mCherry in 21% of cells grown in PYE (n = 2766) (Fig. S7). A similarly constructed strain carrying podJ2-mCherry did not exhibit fluorescence above that of background, and the fusion protein was not detectable by immunoblotting using antibodies against mCherry (Fig. S7). These results further indicate that the podJ2 gene is not functional in Rm1021.

Next, we asked if PodJ1 localizes to a particular side of the cell. In C. crescentus PodJ first appears at the flagellated pole, which is the newer cell pole, generated from the most recent cell division (Fig. 1A). Because, unlike C. crescentus, S. meliloti lacks obvious organelles that distinguish between the two cell poles, we performed time-lapse microscopy to follow the localization pattern of EGFP-PodJ1 through two cell divisions (Fig. 5B). After each cell division, PodJ1 segregates with one cell (daughter cell) but not the other (mother cell). In the daughter cell, the PodJ1 focus disappears and then reappears at the opposite pole as the cell readies itself for another round of division. In contrast, in the mother cell the next PodJ1 focus appears at the same side where it had localized in the previous division. Thus, like PodJ in C. crescentus, PodJ1 in S. meliloti localizes to the newer cell pole, the pole generated by the previous division event (see Fig. 1A).

ΔpodJ1 mutation alters expression of genes involved in diverse cellular activities

Because the ΔpodJ1 mutation led to pleiotropic defects, we asked if PodJ1 exerts some of its control over physiological processes via regulation of gene expression. Affymetrix GeneChip analysis was used to gain insight into the molecular circuits influenced by PodJ1. We found that 129 genes exhibited significant alterations in expression between the wild type and the ΔpodJ1 mutant when grown in LB (Tables 1 and 2). Of the 75 genes that showed decreased expression in the mutant (Table 1), the majority (51) belong to the same, large cluster of flagellar, motility, and chemotaxis genes on the chromosome, the “flagellar regulon” (Sourjik et al., 1998). This result is consistent with the motility defect seen in the ΔpodJ1 mutant. In addition, genes involved in pili biogenesis, particularly two on the chromosome that closely resemble counterparts in the cell cycle-regulated pilus system in C. crescentus (pilA and cpaA), had lowered expression in the mutant. Among the five potential regulatory genes with reduced expression, SMc04011, which encodes an ortholog of the C. crescentus sigma 54-dependent transcriptional regulator TacA, stood out because it had one of the most dramatic changes in expression, second only to that seen for the podJ1 gene, which served as an internal control. In C. crescentus, microarray analysis of a ΔpodJ mutant also revealed lower expression of flagellar and pili genes, as well as tacA (Chen et al., 2006). Thus, a core regulatory circuitry has been conserved across species. However, the set of expression changes seen for S. meliloti ΔpodJ1 is much larger than that seen for the C. crescentus ΔpodJ mutant. PodJ’s regulatory role appears to have been expanded and altered in S. meliloti to suit its specific physiology.

Table 1.

Genes with decreased expression in the ΔpodJ1 mutant, as identified by microarray analysis. Number in parenthesis after each category indicates the number of genes in each functional group. AVG SLR represents average signal log ratio, which was converted to percentage of wild-type expression (% WT) (see Experimental Procedures). STD DEV, standard deviation of the average SLR.

| Name | Gene | Annotation / Description | AVG SLR | STD DEV | % WT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flagellar biosynthesis and motility (51) | |||||

| SMc00975 | mcpU | Methyl-accepting chemotaxis transmembrane protein | −2.16 | 0.41 | 22% |

| SMc01469 | mcpW | Methyl-accepting chemotaxis transmembrane protein | −1.80 | 0.56 | 29% |

| SMc03005 | Conserved hypothetical protein, required for motility | −2.29 | 0.19 | 20% | |

| SMc03006 | cheY1 | Chemotaxis regulator protein | −2.36 | 0.36 | 19% |

| SMc03007 | cheA | Chemotaxis protein (sensory transduction histidine kinase) | −2.12 | 0.15 | 23% |

| SMc03008 | cheW1 | Chemotaxis protein (sensory transduction histidine kinase) | −2.04 | 0.28 | 24% |

| SMc03009 | cheR | Chemotaxis methyltransferase | −1.63 | 0.27 | 32% |

| SMc03010 | cheB1 | Chemotaxis response regulator protein, glutamate methyltransferase | −1.97 | 0.38 | 26% |

| SMc03011 | cheY2 | Chemotaxis regulator protein | −1.93 | 0.24 | 26% |

| SMc03012 | cheD | Chemotaxis protein | −2.46 | 0.28 | 18% |

| SMc03013 | Conserved hypothetical protein | −1.57 | 0.12 | 34% | |

| SMc03014 | fliF | Flagellar M-ring transmembrane protein | −2.99 | 0.39 | 13% |

| SMc03017 | Conserved hypothetical protein | −1.47 | 0.18 | 36% | |

| SMc03019 | fliG | Flagellar motor switch protein | −2.39 | 0.38 | 19% |

| SMc03020 | fliN | Flagellar motor switch protein | −2.88 | 0.34 | 14% |

| SMc03021 | fliM | Flagellar motor switch transmembrane protein | −2.08 | 0.33 | 24% |

| SMc03022 | motA | Transmembrane motility protein A | −3.50 | 0.50 | 9% |

| SMc03023 | Conserved hypothetical protein | −2.48 | 0.34 | 18% | |

| SMc03024 | flgF | Flagellar basal-body rod protein | −2.50 | 0.35 | 18% |

| SMc03025 | fliI | Flagellum-specific ATP synthase protein | −3.41 | 0.57 | 9% |

| SMc03026 | Hypothetical transmembrane protein | −2.28 | 0.66 | 21% | |

| SMc03027 | flgB | Flagellar basal-body rod protein | −3.45 | 0.36 | 9% |

| SMc03028 | flgC | Flagellar basal-body rod protein | −3.14 | 0.36 | 11% |

| SMc03029 | fliE | Flagellar hook-basal body complex protein | −3.36 | 0.49 | 10% |

| SMc03030 | flgG | Flagellar basal-body rod protein | −3.29 | 0.36 | 10% |

| SMc03031 | flgA | Flagellar precursor transmembrane protein | −3.12 | 0.41 | 12% |

| SMc03032 | flgI | Flagellar P-ring precursor transmembrane protein | −2.01 | 0.40 | 25% |

| SMc03033 | motE | Chaperone specific for MotC folding and stability | −3.00 | 0.34 | 13% |

| SMc03034 | flgH | Flagellar L-ring protein precursor (basal body L-ring protein) | −2.39 | 0.30 | 19% |

| SMc03035 | fliL | Flagellar transmembrane protein | −2.38 | 0.30 | 19% |

| SMc03037 | flaA | Flagellin A protein | −3.10 | 0.34 | 12% |

| SMc03038 | flaB | Flagellin B protein | −1.80 | 0.59 | 29% |

| SMc03039 | flaD | Flagellin D protein | −2.02 | 0.45 | 25% |

| SMc03040 | flaC | Flagellin C protein | −2.07 | 0.30 | 24% |

| SMc03041 | Conserved hypothetical protein, required for flagellation | −3.17 | 0.84 | 11% | |

| SMc03042 | motB | Transmembrane motility protein B | −1.58 | 0.27 | 33% |

| SMc03043 | motC | Transmembrane chemotaxis precursor motility protein C | −3.25 | 0.60 | 11% |

| SMc03044 | fliK | Hook length control protein | −2.29 | 0.72 | 20% |

| SMc03045 | Conserved hypothetical signal peptide protein | −1.80 | 0.47 | 29% | |

| SMc03046 | rem | Response regulator of exponential growth motility | −2.71 | 0.66 | 15% |

| SMc03047 | flgE | Flagellar hook protein | −2.64 | 0.23 | 16% |

| SMc03048 | flgK | Flagellar hook-associated protein | −2.71 | 0.29 | 15% |

| SMc03049 | flgL | Flagellar hook-associated protein | −2.85 | 0.43 | 14% |

| SMc03050 | flaF | Flagellin synthesis regulator protein | −2.54 | 0.31 | 17% |

| SMc03051 | flbT | Flagellin synthesis repressor protein | −2.28 | 0.30 | 21% |

| SMc03052 | flgD | Basal-body rod modification protein | −2.83 | 0.40 | 14% |

| SMc03053 | fliQ | Flagellar biosynthetic transmembrane protein | −0.89 | 0.17 | 54% |

| SMc03054 | flhA | Flagellar biosynthetic transmembrane protein | −1.79 | 0.24 | 29% |

| SMc03057 | Conserved hypothetical transmembrane protein | −1.86 | 0.52 | 28% | |

| SMc03071 | Hypothetical protein | −2.01 | 0.35 | 25% | |

| SMc03072 | Conserved hypothetical protein | −2.33 | 0.33 | 20% | |

| Pili Biogenesis (4) | |||||

| SMc00159 | Flp pilus assembly protein TadG homolog | −1.25 | 0.62 | 42% | |

| SMc04059 | Flp pilus assembly protein TadG homolog | −2.02 | 0.68 | 25% | |

| SMc04113 | cpaA1 | Transmembrane pilus assembly protein | −1.46 | 0.45 | 36% |

| SMc04114 | pilA1 | Pilin subunit protein | −2.93 | 0.77 | 13% |

| Regulators (5) | |||||

| SMc00887 | Diguanylate cyclase/phosphodiesterase | −1.90 | 0.28 | 27% | |

| SMc00888 | Two-component receiver domain protein | −1.67 | 0.41 | 31% | |

| SMc01768 | MarR family transcription regulator | −1.86 | 0.54 | 28% | |

| SMc02061 | bioS | Biotin-regulated, LysR-like transcription factor | −1.67 | 0.39 | 31% |

| SMc04011 | tacA | σ-54-dependent transcription regulator | −4.12 | 1.02 | 6% |

| Miscellaneous (6) | |||||

| SMb20649 | nadE1 | Ammonium-dependent NAD+ synthetase protein | −1.75 | 0.30 | 30% |

| SMb20650 | Long-chain fatty-acid-CoA ligase protein | −2.51 | 0.51 | 18% | |

| SMb20651 | Acyl carrier protein | −2.07 | 0.46 | 24% | |

| SMb20652 | asnB | Asparagine synthetase protein | −2.15 | 0.65 | 23% |

| SMc00003 | Chaperone protein | −1.18 | 0.16 | 44% | |

| SMc02230 | podJ1 | Polar localization factor | −5.96 | 0.84 | 2% |

| Hypothetical proteins (9) | |||||

| SMb20464 | Hypothetical protein | −2.12 | 0.25 | 23% | |

| SMc00456 | Conserved hypothetical signal peptide protein | −0.79 | 0.27 | 58% | |

| SMc00849 | Hypothetical protein | −1.89 | 0.57 | 27% | |

| SMc00924 | Hypothetical protein | −2.45 | 1.06 | 18% | |

| SMc00925 | Conserved hypothetical signal peptide protein | −0.83 | 0.34 | 56% | |

| SMc00986 | Hypothetical protein | −1.96 | 0.28 | 26% | |

| SMc02392 | Hypothetical protein | −1.52 | 0.35 | 35% | |

| SMc03746 | Hypothetical protein | −1.73 | 0.23 | 30% | |

| SMc04280 | Hypothetical signal peptide protein | −1.05 | 0.30 | 48% | |

Table 2.

Genes with increased expression in the ΔpodJ1 mutant, as identified by microarray analysis. Number in parenthesis after each category indicates the number of genes in each functional group. AVG SLR represents average signal log ratio, which was converted to percentage of wild-type expression (% WT) (see Experimental Procedures). STD DEV, standard deviation of the average SLR.

| Name | Gene | Annotation / Description | AVG SLR | STD DEV | % WT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exopolysaccharide biosynthesis (16) | |||||

| SMa1587 | eglC | Endo-1,3-1,4-β-glycanase | 0.80 | 0.34 | 174% |

| SMb20806 | Conserved hypothetical glycosyltransferase family A homolog | 0.60 | 0.25 | 152% | |

| SMb20944 | exoQ | Polysaccharide polymerase, similar to Wzy protein | 0.80 | 0.34 | 174% |

| SMb20945 | exoF1 | Periplasmic polysaccharide export protein | 0.79 | 0.30 | 173% |

| SMb20949 | exoV | Pyruvyltransferase protein | 0.69 | 0.21 | 161% |

| SMb20950 | exoT | Exopolysaccharide transport protein, similar to Wzx | 1.01 | 0.50 | 201% |

| SMb20955 | exoK | Licheninase | 1.05 | 0.72 | 207% |

| SMb20957 | exoA | Glycosyltransferase, succinoglycan biosynthesis protein | 0.97 | 0.37 | 196% |

| SMb20958 | exoM | Succinoglycan biosynthesis protein | 0.84 | 0.41 | 179% |

| SMb20959 | exoO | Exopolysaccharide glucosyltransferase protein | 0.89 | 0.13 | 185% |

| SMb20960 | exoN | UDPglucose pyrophosphorylase protein | 1.01 | 0.20 | 201% |

| SMb20961 | exoP | MPA1 family tyrosine kinase, succinoglycan chain-length determinant | 0.93 | 0.29 | 191% |

| SMb21189 | Glycosyltransferase protein | 0.98 | 0.36 | 197% | |

| SMb21314 | wgeA | Galactoglucan biosynthesis | 0.62 | 0.26 | 154% |

| SMb21690 | exoW | Glucosyltransferase protein | 0.91 | 0.41 | 188% |

| SMc03900 | ndvA | β-1,2-glucan export ATP-binding protein | 0.93 | 0.48 | 191% |

| Regulators (3) | |||||

| SMa0748 | MucR family transcription regulator | 0.72 | 0.15 | 165% | |

| SMc00170 | sinR | Quorum sensing system, AHL autoinducer-binding, LuxR family regulator | 0.44 | 0.19 | 136% |

| SMc00943 | wrbA1 | Trp repressor-binding protein | 0.67 | 0.10 | 159% |

| Cell division (2) | |||||

| SMb21523 | minD | Cell division inhibitor protein | 0.33 | 0.11 | 126% |

| SMc04296 | ftsZ2 | Cell division protein | 0.49 | 0.10 | 140% |

| Miscellaneous (8) | |||||

| SMa1811 | Hypothetical metallo-β-lactamase homolog | 0.71 | 0.16 | 164% | |

| SMa1821 | Hydrolase | 0.82 | 0.44 | 177% | |

| SMa2379 | katB | Catalase/peroxidase | 0.58 | 0.10 | 149% |

| SMb20170 | fdh | S-(hydroxymethyl) glutathione dehydrogenase protein | 2.29 | 0.94 | 489% |

| SMb20204 | pqqA | Pyrroloquinoline quinone synthesis protein A | 1.03 | 0.55 | 204% |

| SMb20999 | bacA | Transport protein, essential for bacteroid development | 0.62 | 0.12 | 154% |

| SMc00040 | OsmC-like organic hydroperoxide resistance protein | 0.43 | 0.08 | 135% | |

| SMc04236 | Glycine-rich cell wall structural transmembrane protein | 0.74 | 0.18 | 167% | |

| Hypothetical proteins (26) | |||||

| SMa2297 | Hypothetical protein | 1.08 | 0.27 | 211% | |

| SMb20273 | Hypothetical protein | 0.77 | 0.31 | 171% | |

| SMb20336 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 0.50 | 0.12 | 141% | |

| SMb20771 | Conserved hypothetical exported protein | 0.70 | 0.24 | 162% | |

| SMb20808 | Membrane-anchored protein | 0.52 | 0.18 | 143% | |

| SMb20837 | Hypothetical protein | 2.03 | 0.38 | 408% | |

| SMb20838 | Secreted calcium-binding protein | 1.41 | 0.37 | 266% | |

| SMb21440 | Conserved hypothetical signal peptide protein | 1.13 | 0.83 | 219% | |

| SMc00062 | Hypothetical protein | 0.99 | 0.41 | 199% | |

| SMc00141 | Hypothetical OmpA homolog | 1.13 | 0.40 | 219% | |

| SMc00198 | Hypothetical protein | 1.40 | 0.35 | 264% | |

| SMc00252 | Hypothetical signal peptide protein | 1.08 | 0.20 | 211% | |

| SMc00809 | Hypothetical signal peptide protein | 1.39 | 0.57 | 262% | |

| SMc01016 | Hypothetical protein | 1.07 | 0.51 | 210% | |

| SMc01557 | Hypothetical signal peptide protein | 1.06 | 0.28 | 208% | |

| SMc01586 | Hypothetical transmembrane protein, Brucella BA14K homolog | 0.95 | 0.32 | 193% | |

| SMc01774 | Hypothetical transmembrane protein | 0.74 | 0.39 | 167% | |

| SMc01788 | Hypothetical protein | 0.51 | 0.21 | 142% | |

| SMc02156 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 0.59 | 0.15 | 151% | |

| SMc02266 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 0.86 | 0.42 | 182% | |

| SMc02317 | Hypothetical signal peptide protein | 0.56 | 0.25 | 147% | |

| SMc02388 | Hypothetical transmembrane protein | 1.32 | 0.64 | 250% | |

| SMc02389 | Hypothetical transmembrane protein | 1.51 | 0.60 | 285% | |

| SMc03100 | Hypothetical signal peptide protein | 0.54 | 0.21 | 145% | |

| SMc03108 | Hypothetical calcium-binding protein | 1.16 | 0.39 | 223% | |

| SMc04246 | Hypothetical transmembrane signal peptide protein | 0.84 | 0.30 | 179% | |

In C. crescentus, microarray analysis of the ΔpodJ mutant did not show significant increases in gene expression (Chen et al., 2006). In contrast, 55 genes increased their expression in the S. meliloti ΔpodJ1 mutant (Table 2). The majority of these genes have no known function. Nevertheless, some of the changes in expression correlated with the observed phenotypes. First, several exo genes, involved in succinoglycan synthesis, exhibited elevated expression in the mutant, thus accounting for the increase in calcofluor binding. Second, ndvA, which encodes an ABC transporter required for cyclic beta-glucan export, was up-regulated, and its expression depends on the FeuP/Q pathway, which was shown to respond to low osmolarity (Griffitts et al., 2008). Stimulation of ndvA expression in LB suggests that in the absence of PodJ1 cells perceive a hypotonic environment even in media with relatively high salt concentrations. Perhaps the mutant’s cell envelope defect leads to leakage of compatible solutes or interferes with the detection of osmotic conditions. Third, in the same vein, elevated bacA expression in the ΔpodJ1 strain (154% relative to wild-type) may also be linked to cell envelope defects, as BacA is required for normal lipid A synthesis and bacterioid development (Glazebrook et al., 1993; Ferguson et al., 2004). Finally, heightened expression of two cell division genes, minD and ftsZ2, may reflect an imbalance of factors that coordinate cytokinesis, which would generate the branching morphology seen in the mutant. In summary, we observed corresponding changes in gene expression for all detectable phenotypes of the ΔpodJ1 mutant. Genes with unknown functions that were identified by the microarray analysis may participate in the same or other PodJ1-influenced set of molecular activities.

To verify the microarray data, we used previously generated transcriptional fusions of the uidA reporter or constructed new fusions to select genes, at their native loci, that minimized disruption to the genomic sites. Beta-glucuronidase activity was measured in both the wild-type and ΔpodJ1 mutant backgrounds to compare expression levels of these candidates. Results from this analysis of 13 transcriptional fusions agreed with results from the microarray analysis (Table 3): the magnitudes of the changes were consistent between the two assay techniques. For example, pilA1 (SMc04114) expression in the mutant was 13% that of wild-type according to the microarray analysis and 19% according to the transcriptional fusion analysis. Because the minCDE genes are transcribed as an operon (Cheng et al., 2007), and minD (SMb21523) and minE (SMb21522) appear to be translationally coupled, we inserted the uidA reporter after minE, which comes after minD, to prevent polar effects. This fusion suggested that the min genes are up-regulated in the ΔpodJ1 mutant, but only minD showed significant alteration in expression in the microarray analysis. Also, we had used a transcriptional fusion to assess expression of mcpX (SMc01104), a chemoreceptor gene that did not turn up in the microarray analysis, and it showed significant down-regulation in the ΔpodJ1 mutant (Table 3). Examination of the raw microarray data (Table S1) indicated that both minE and mcpX exhibited changes in expression in some of the pairwise comparisons, but the changes were insufficiently consistent to be deemed significant by the data analysis software. In the case of mcpX, both the Affymetrix GeneChip data and the transcriptional fusion assays suggested that its relatively low level of expression, in both the wild-type and mutant, may contribute to a difficulty in detection. Nevertheless, in sum, the transcriptional fusion analysis validated the microarray results. Furthermore, it indicated that changes declared as significant by the microarray analysis represent reliable, conservative estimates of the actual alterations in gene expression. Although relatively small alterations in expression, such as that of the min operon, are observable by the different methods, the physiological impacts of such subtle changes should be interpreted with caution.

Table 3.

Transcriptional fusions to uidA confirm that PodJ1 affects expression of diverse genes.

| Gene | LB | PYE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rm1021 | ΔpodJ1 | Ratio | Rm1021 | ΔpodJ1 | Ratio | |

| Increased expression in ΔpodJ1 | ||||||

| SMb20838 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 252% | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 728% |

| SMb20999 (bacA) | 11.0 ± 2.3 | 15.2 ± 5.1 | 138% | 6.9 ± 1.8 | 7.2 ± 2.3 | 104% |

| SMb21522 (minE) | 15.5 ± 2.5 | 21.3 ± 1.9 | 138% | 14.8 ± 2.7 | 19.7 ± 3.7 | 133% |

| SMc02389 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 280% | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 3.3 ± 0.6 | 229% |

| SMc03108 | 21.6 ± 3.7 | 47.0 ± 11.1 | 217% | 25.2 ± 3.6 | 33.8 ± 3.5 | 134% |

| SMc04296 (ftsZ2) | 24.6 ± 0.9 | 38.1 ± 3.7 | 155% | 39.5 ± 6.3 | 46.7 ± 8.3 | 118% |

| Decreased expression in ΔpodJ1 | ||||||

| SMc00887 | 7.9 ± 0.9 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 25% | 32.4 ± 5.2 | 20.7 ± 2.9 | 64% |

| SMc00888 | 20.1 ± 1.6 | 5.2 ± 1.2 | 26% | 90.4 ± 16.0 | 55.5 ± 5.2 | 61% |

| SMc00975 (mcpU) | 5.6 ± 1.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 23% | 58.5 ± 8.5 | 37.8 ± 6.4 | 65% |

| SMc01104 (mcpX) | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 14% | 8.7 ± 2.4 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 23% |

| SMc03040 (flaC) | 5.6 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 26% | 10.0 ± 1.6 | 8.0 ± 1.4 | 80% |

| SMc04011 (tacA) | 20.8 ± 4.8 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 3% | 42.1 ± 4.6 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 4% |

| SMc04114 (pilA1) | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 19% | 8.4 ± 1.8 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 10% |

Beta-glucuronidase activity (± standard deviation, in Miller units) of strains grown in LB or PYE was measured as described in Experimental Procedures. Ratio equals the enzymatic activity in the mutant divided by that in the Rm1021 wild-type. Expression is significantly different between the two strains in all comparisons (p < 0.01), except for SMb20999 (bacA) in PYE.

The uidA transcriptional fusions also allowed examination of gene expression in PYE, a more permissive media for the ΔpodJ1 mutant (Table 3). In general, differences between wild type and mutant were reduced in PYE when compared to growth in LB. For example, there was no longer significant variation in bacA expression. Thus, in agreement with results from phenotypic analysis, environmental conditions influence PodJ1’s regulation of cell envelope functions. A minority of the reporter fusions (to SMb20838, SMc04011, and SMc04114) showed the same or more dramatic variations in expression. Growth in PYE may enhance specific distinctions between wild type and mutant: for instance, PYE appears to increase expression of SMc04114 (pilA1) in the wild-type, but the podJ1 deletion prevents a similar increase. As for SMc04011 (tacA), which shows similarly reduced levels of expression in both LB and PYE, it may serve as a core component of PodJ1’s regulatory circuit, such that its expression is independent of environmental conditions. Unraveling how external factors affect PodJ1’s control of gene expression, whether direct or indirect, will require further investigation.

Suppressor analysis reveals genetic interactions between podJ1 and cell envelope-associated factors

While characterizing the cell envelope defects of the ΔpodJ1 mutant, we noticed that colonies exhibiting more robust growth on LBLS plates arose at a frequency of 1 in 106. We inferred that these colonies contained bacteria carrying spontaneous suppressor mutations. To facilitate the identification of factors that interact genetically with podJ1, and thus contribute to cell envelope-associated functions in S. meliloti, we isolated transposon insertion mutations that suppressed the ΔpodJ1 mutant’s sensitivity to LB media with lower salt concentrations. We used Tn5–110 (Griffitts and Long, 2008) to mutagenize the ΔpodJ1 strain and collected approximately 30,000 isolates with random insertions. Selection on LBLS plates, followed by phenotype confirmation via secondary screens, yielded 23 candidate suppressors (see Experimental Procedures for details).

We then sequenced arbitrarily-primed PCR products to determine the locations of the transposon insertions (Griffitts and Long, 2008). The 23 ΔpodJ1 suppressor isolates represented interruptions in nine different genes, as five of the insertions were isolated at least twice, and four genes received at least two independent interruptions (Table 4). A majority of the interrupted genes (6 out of 9) encode proteins with cell envelope-associated characteristics, but none have experimentally defined activities. Based on their annotations, SMc00457 and SMc02555 encode hypothetical proteins that are targeted to the cell envelope. SMc02219 encodes a periplasmic solute-binding protein whose expression is induced by specific amino acids (Mauchline et al., 2006). SMc00067, SMc00122, and SMc03872 encode a lipoprotein, a penicillin-binding protein, and a protease, respectively, which may all participate in the modification of cell envelope structures; while SMc03855 encodes a 2-methylthioadenine synthetase and SMc03996 a thiamine-phosphate pyrophosphorylase, both cytoplasmic enzymes. Notably, the expression of SMc00067, SMc03855, SMc03872, and SMc3996 are all elevated in a tolC mutant, which exhibits heightened stress responses (Santos et al., 2010). The final and most intriguing suppressor candidate is the ortholog of the C. crescentus membrane-bound histidine kinase PleC, encoded by SMc02369 (39% identity, 57% similarity, with 74% coverage) (Hallez et al., 2004; Johnson et al., 2008; Brilli et al., 2010). Because PleC has been shown to act in the same pathway as PodJ in C. crescentus (Viollier et al., 2002a; Hinz et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2006), identification of SMc02369 (henceforth called pleCSm) in the suppressor analysis validated this genetic approach.

Table 4.

Transposon insertions that suppressed the ΔpodJ1 mutant’s sensitivity to LBLS.

| Gene | Genome locationa | Annotation / Description | PSORTb | Tn5–110 insertionsc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMc00067 | 1107235→1107645 | lppA (putative lipoprotein) | Extracellular (Outer membrane) | 1107356 (Rev) [2], 1107487 (Rev) |

| SMc00122 | 1100913←1103147 | pbp (putative penicillin-binding protein) | Inner membrane | 1102099 (Rev), 1102467 (Rev) |

| SMc00457 | 1100228←1100815 | hypothetical transmembrane protein (DUF1214 superfamily) | Inner membrane | 1100379 (Rev) |

| SMc02219 | 581426→582349 | putative amino acid-binding periplasmic protein | Periplasmic | 581597 (Rev) [2], 581779 (For), 582227 (For) [3], 582268 (For) |

| SMc02369 | 1119019←1121337 | sensor histidine kinase transmembrane protein (pleCSm) | Inner membrane | 1121237 (For) [3] |

| SMc02555 | 1206725←1207168 | putative signal peptide protein (DUF2385 superfamily) | Unknown | 1206837 (For), 1206913 (For), 1206923 (For) |

| SMc03855 | 3519890←3521164 | putative 2-methylthioadenine synthetase | Cytoplasmic | 3520402 (Rev) [2] |

| SMc03872 | 3536747→3538240 | putative Zn-dependent protease | Unknown | 3537402 (Rev) |

| SMc03996 | 2994503←2995156 | thiE2 (thiamine-phosphate pyrophosphorylase) | Cytoplasmic | 2994619 (For) |

Arrows in the genome location column indicate directionality of the genes.

Subcellular locations of gene products were predicted by PSORTb v.3.0.2 (Yu et al., 2010). The product of SMc00067 contains characterictics of an outer membrane lipoprotein (Galibert et al., 2001), but PSORTb does not detect lipoprotein motifs.

Chromosomal positions of the transposon insertions are as shown. For or Rev indicates the directionality of the Tn5–110 insertion; for example, 1107356 (Rev) means that bp 1107356 of the chromosome is the first bp encountered when the trp promoter reads out of the transposon, whereas 581779 (For) means that bp 581779 is the first bp encountered by readthrough transcription from the neomycin-resistance gene. Numbers in brackets indicate the number of isolates obtained with a particular insertion.

To confirm that suppression of the LBLS sensitivity is due to loss of function of the interrupted genes, we constructed in-frame deletions of the candidate suppressors. Seven of the nine candidates were amenable to such allelic replacements, which produced similar suppression of the LBLS sensitivity in the ΔpodJ1 background as their corresponding transposon insertions (Table 5 and Fig. S8). The inability to delete two of the candidates (pleCSm and SMc03996) in both wild-type and ΔpodJ1 backgrounds after repeated attempts suggested that they might be essential for viability. Indeed, we were able to obtain a chromosomal deletion of pleCSm only by introducing a plasmid carrying a complementing copy of the gene (pJC456). Furthermore, this marked deletion allele (ΔpleCSm::Ω) could be transduced into both wild-type and ΔpodJ1 strains carrying the complementing plasmid but not into ones carrying the vector alone. Hence, unlike C. crescentus pleC, which is not required for viability (Sommer and Newton, 1989; Viollier et al., 2002b), pleCSm appears to be an essential gene (see additional confirmation below).

Table 5.

Phenotypic characterization of ΔpodJ1 suppressors.

| Genotypea | Motilityb | PYE | LB | LBLS | Deoxych | Calcofluorc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rm1021 (wild-type) | 100% | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | 100% | |

| ΔSMc00067 | 109% | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | 70% ± 11% | ** |

| ΔSMc00122 | 103% | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | 73% ± 30% | ** |

| ΔSMc00457 | 106% | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | 79% ± 28% | ** |

| ΔSMc02219 | 110% | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | 78% ± 28% | * |

| ΔSMc02555 | 109% | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | 81% ± 31% | * |

| ΔSMc03855 | 109% | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | 91% ± 14% | * |

| ΔSMc03872 | 108% | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | 71% ± 19% | ** |

| SMc03996::Tn5 | 102% | ++ | ++ | +++ | + | 48% ± 10% | ** |

| pleCSm::Tn5 | 101% | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | 102% ± 7% | |

| Rm1021 / P-pleCSm | 99% | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | 110% ± 14% | |

| ΔpodJ1 | 36% | +++ | +++ | − | − | 163% ± 48% | ** |

| ΔpodJ1 ΔSMc00067 | 50% | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | 76% ± 12% | ^^ |

| ΔpodJ1 ΔSMc00122 | 44% | +++ | +++ | ++ | − | 148% ± 59% | ^^ |

| ΔpodJ1 ΔSMc00457 | 45% | +++ | +++ | ++ | − | 133% ± 44% | ^ |

| ΔpodJ1 ΔSMc02219 | 42% | +++ | +++ | ++ | − | 155% ± 61% | ^^ |

| ΔpodJ1 ΔSMc02555 | 45% | +++ | +++ | ++ | − | 134% ± 47% | ^^ |

| ΔpodJ1 ΔSMc03855 | 41% | +++ | +++ | + | − | 106% ± 32% | ^^ |

| ΔpodJ1 ΔSMc03872 | 45% | ++ | +++ | ++ | +/− | 93% ± 38% | ^^ |

| ΔpodJ1SMc03996::Tn5 | 62% | ++ | ++ | + | − | 70% ± 18% | ^^ |

| ΔpodJ1pleCSm::Tn5 | 59% | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | 158% ± 29% | |

| ΔpodJ1 / P-pleCSm | 50% | +++ | +++ | ++ | + | 158% ± 34% | |

The ability of strains to grow on various media was compared to that of wild-type Rm1021: +++ indicates the best growth, while − indicates the worst or no growth. Deoxych indicates LB plates containing 0.1% sodium deoxycholate.

P-pleCSm represents Plac-PpleC-pleCSm, which allows moderate overexpression of pleCSm from pJC466.

The diameters of motility swarms on soft-agar plates were compared to those of the wild-type at least three independent times and the resultant ratios averaged. Standard deviation for each average was less than 10%. The average diameter of the wild-type swarm after 3 days in PYE was 17 mm.

Relative fluorescence intensity (± standard deviation) on plates containing Calcofluor is the average of at least 12 different dilution spots; * if 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05, ** if p ≤ 0.01, when compared to wild-type; ^ if 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05, ^^ if p ≤ 0.01, when compared to ΔpodJ1.

The transposon insertion in pleCSm that enabled suppression of ΔpodJ1 sits near the 5’ end of the gene (Table 4). Knowing that Tn5–110 allows constitutive outward transcription from both ends (Griffitts and Long, 2008) and that in C. crescentus PleC acts downstream of PodJ (Viollier et al., 2002a; Hinz et al., 2003), we suspected that overexpression of PleCSm in the ΔpodJ1 background suppressed the LBLS sensitivity. To test this idea, we first used a low-copy-number plasmid (pJC456) with pleCSm under the control of its own promoter (PpleC). While this plasmid complemented the pleCSm null allele, it failed to suppress the ΔpodJ1 mutation. A plasmid (pJC465) with pleCSm under the control of a constitutive promoter (Plac) also failed to ameliorate the mutant’s growth defect on LBLS. However, when we placed pleCSm, together with its upstream region, after the constitutive Plac promoter on a plasmid (pJC466), the construct (Plac-PpleC-pleCSm) replicated the suppression caused by the Tn5–110 insertion in pleCSm (Table 5 and Fig. S8), thus confirming our suspicion. An appropriate level of constitutive pleCSm expression appears critical for suppression of the ΔpodJ1 phenotype.

Although suppression by the pleCSm::Tn5–110 allele can be attributed to constitutive expression of pleCSm, the means by which SMc03996::Tn5–110 suppresses ΔpodJ1 remains obscure. The insertion sits near the 3’ end of the gene, truncating the last 38 codons of a 217-amino acid protein. Thus, overexpression seems an unlikely explanation. Another complicating factor is that the gene product, annotated as a thiamine-phosphate pyrophosphorylase, appears to be essential for viability. One possible rationalization is that the truncated protein retains sufficient function to prevent cell death yet alters cellular physiology in a way that suppresses the ΔpodJ1 phenotype. Another possibility is that the SMc03996::Tn5–110 insertion alters the expression of surrounding genes, to allow growth of ΔpodJ1 on LBLS. Because other transposon insertions yielded more approachable suppressor candidates, we chose to concentrate on analyzing those.

The remaining seven candidate genes were deleted in both the wild-type and ΔpodJ1 backgrounds, and the resultant single or double mutants were examined for changes in motility, calcofluor binding, sensitivity to deoxycholate, and other growth phenotypes (Table 5 and Fig. S8). In addition, strains carrying the SMc03996::Tn5–110 or pleCSm::Tn5–110 insertion or the pleCSm overexpression plasmid were included in the phenotypic analysis for comparison (Table 5 and Fig. S8). None of these genetic changes affected motility in the wild-type background. In the ΔpodJ1 background, although the suppressors, particularly the Tn5–110 insertions in SMc03996 and pleCSm, generally increased the diameters of the motility swarms, the improvements were small. Thus, none of the suppressor genes appear to be involved in the regulation of motility, or at least in a way that can rescue the defect caused by the ΔpodJ1 mutation.

Although all the suppressor mutations improved growth of the ΔpodJ1 strain on LBLS, only a few alleviated its increased sensitivity to deoxycholate (Table 5 and Fig. S8): ΔSMc00067 allowed significantly better growth of the ΔpodJ1 mutant on LB containing 0.1% deoxycholate, ΔSMc03872 offered minute enhancement, while both pleCSm::Tn5–110 and the pleCSm overexpression plasmid provided an intermediate level of improvement. In contrast, some of the suppressor deletions caused increased sensitivity to deoxycholate in the wild-type background (ΔSMc00122, ΔSMc00457, ΔSMc02219, and ΔSMc03872), suggesting that the presence of these genes may contribute to the structural integrity of the cell envelope. The SMc03996::Tn5–110 insertion also led to poor growth of the wild type on LB containing deoxycholate. Thus, while it allowed better growth of the ΔpodJ1 mutant on LBLS, the SMc03996::Tn5–110 insertion compromised the cell’s tolerance for other environmental stresses. Similarly, ΔSMc03872 increased the ΔpodJ1 mutant’s tolerance for LBLS but prevented it from growing well on PYE media. These results suggest that complex interactions exist among PodJ1 and multiple cellular factors that help maintain physiological adaptations against environmental assaults.

We found the most consistent correlation of the suppressors’ effects between LBLS resistance and succinoglycan production. All seven suppressor deletions appeared to reduce the level of succinoglycan production in both the wild-type and ΔpodJ1 backgrounds, as judged by the intensity of calcofluor fluorescence (Table 5 and Fig. S8). In particular, while the ΔpodJ1 mutant exhibited increased fluorescence compared to wild-type, the addition of a SMc00067, SMc03855, or SMc03872 deletion in the mutant brought the average intensity down to near or below wild-type levels. Hence, all seven suppressor genes contribute to the regulation of succinoglycan synthesis. The SMc03996::Tn5–110 insertion also decreased greatly the level of calcofluor binding, but part of that decrease may be attributed to the generally less robust growth of strains carrying the insertion, as they tended to form smaller colonies on PYE or LB, and colony density positively influenced fluorescence intensity. Finally, neither the pleCSm::Tn5–110 insertion or the pleCSm overexpression plasmid significantly altered calcofluor binding in the wild-type and ΔpodJ1 backgrounds. The signaling pathway of PleCSm may not contribute to the regulation of succinoglycan production, or a redundant mechanism ensures the appropriate level of production even when the PleCSm pathway malfunctions.

Because a majority of the genetic suppressors inhibited succinoglycan production, we assessed whether alteration of succinoglycan levels itself rescues the physiological defects of the ΔpodJ1 mutant. A mutation in exoY or exoS that abolished or increased succinoglycan production, respectively (Doherty et al., 1988; Reuber and Walker, 1993; Yao et al., 2004), was introduced into the ΔpodJ1 mutant. The resultant double mutants exhibited succinoglycan levels similar to those seen in the exoY and exoS parents (Fig. S9). The exoY mutation did not ameliorate any of the defects caused by ΔpodJ1, while the exoS mutation provided very minor protection on LBLS. Therefore, ΔpodJ1 mutant’s cell envelope-associated defects are not caused by succinoglycan overproduction. Instead, the more likely possibilities are that mutant cells increase exopolysaccharide production in response to the cell envelope deficiency, or succinoglycan production and cell envelope integrity are regulated by shared pathways.

Depletion of PleCSm leads to a lethal cell division defect

Since C. crescentus PleC (PleCCc) depends on PodJ for polar localization (Viollier et al., 2002a; Hinz et al., 2003; Lawler et al., 2006), and its ortholog appeared in our suppressor analysis of the ΔpodJ1 mutant, we attempted to localize PleCSm in S. meliloti. Plasmids carrying fusion constructs were integrated into the chromosome such that PleCSm-GFP or -mCherry would be expressed from the endogenous locus. Examination of these strains by fluorescence microscopy revealed only faint, diffuse fluorescence and no obvious localization patterns (data not shown). Similar attempts in S. medicae WSM419 and S. fredii NGR234 with their respective orthologs (Smed0641 and NGRc07870) (Johnson et al., 2008; Brilli et al., 2010) also failed to detect localization (data not shown).

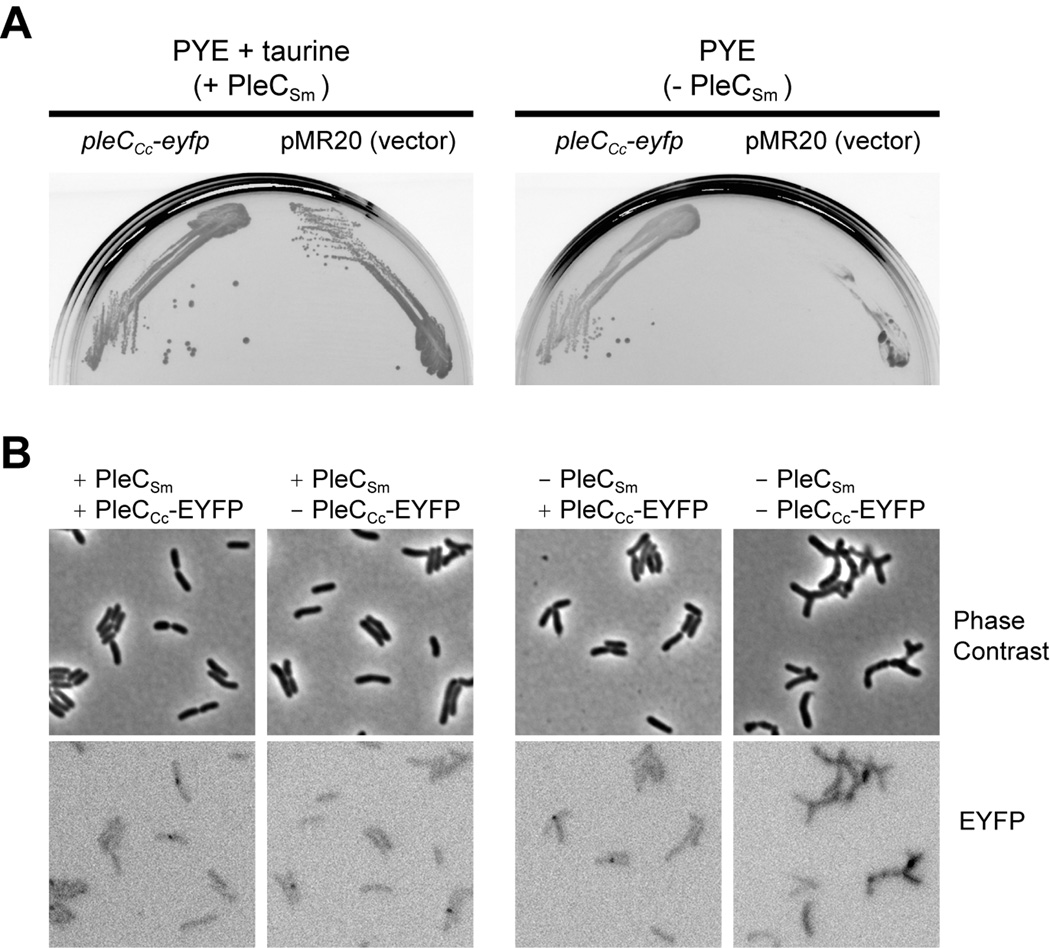

To show that PodJ1 and PleCSm act in the same pathway, we generated a depletion strain in which the only copy of pleCSm is under the control of a taurine-dependent promoter (Ptau) (Mauchline et al., 2006; Griffitts et al., 2008), by integrating Ptau upstream of chromosomal pleCSm. This strain (JOE3601) formed colonies on PYE media containing 100 mM taurine but not on plates without taurine (Fig. 6A). We obtained the same result by complementing a chromosomal deletion of pleCSm with a plasmid carrying the Ptau-pleCSm construct (data not shown). These depletion strains grew normally in liquid media containing taurine, but approximately six to seven generations (20 hours) after shifting into media without taurine, their doublings slowed and eventually stopped. Cells depleted of PleCSm exhibited the same branching morphology (Fig. 6B), indicative of a cell division defect, seen in ΔpodJ1 cells when grown in restrictive media such as LBLS. Thus, PleCSm is essential for viability and normal cell cycle progression. Moreover, in combination with the suppressor analysis demonstrating that constitutive pleCSm expression ameliorates defects caused by the ΔpodJ1 mutation, the similarity in morphology suggests that PodJ1 contributes to normal PleCSm activity and that some of the ΔpodJ1 phenotypes reflect physiological deficiencies caused by a disruption in the regulation of PleCSm.

Fig. 6.

C. crescentus PleC (PleCCc) can substitute for its orthlog in S. meliloti (PleCSm). An S. meliloti PleC depletion strain (JOE3601) was generated by placing the chromosomal pleCSm under the control of a taurine-regulated promoter, such that expression is induced in the presence of taurine (+ PleCSm). A low-copy-number plasmid that carries the pleCCc-eyfp fusion was then introduced into the depletion strain, which was grown without taurine supplementation (− PleCSm) to assess complementation. The vector (pMR20) itself was also introduced for comparison. (A) The strain that expresses PleCCc-EYFP (left side of each plate) formed robust colonies on PYE plates in the presence or absence of taurine, while the depletion strain carrying the vector (right side of each plate) grew only on plates containing 100 mM taurine. (B) Strains were grown in liquid PYE in the presence or absence of taurine and examined by microscopy. The depletion strain that expressed PleCCc-EYFP exhibited normal morphology, while the depletion strain without PleCCc-EYFP stopped growing after 20 hours in the absence of taurine and formed cells with branching morphology. Under fluorescence microscopy, cells expressing PleCCc-EYFP did not exhibit obvious localization patterns, and they appeared as dim as control cells without EYFP. However, when image intensity was adjusted to visualize low levels of fluorescence, fluorescent foci were observed at the septa of some dividing cells, even those that do not carry any eyfp allele (bottom row). This septal localization pattern appears to represent the intrinsic fluoresence of S. meliloti cells.

To establish that the regulatory relationship between PodJ and PleC in C. crescentus has been preserved in S. meliloti, we determined whether PleCCc can substitute for PleCSm. A pleCCc-eyfp fusion allele, used previously to demonstrate polar localization of PleC in C. crescentus (Lam et al., 2003), was introduced into the PleCSm depletion strain on a low-copy-number plasmid (pMR20). This strain formed healthy colonies on plates with or without taurine, whereas a strain bearing the vector alone depended on taurine for growth (Fig. 6A), indicating that PleCCc can replace PleCSm. We also examined by fluorescence microscopy the localization of PleCCc-EYFP in these S. meliloti cells. Regardless of whether PleCSm was present or absent, no obvious localization pattern for PleCCc-EYFP was found. When the images were overexposed, we observed fluorescent foci at the septa of some dividing cells, but this was also true in strains not expressing any EYFP (Fig. 6B). The background fluorescence of S. meliloti cells appears to contribute to these septal foci seen with our YFP filter set. Although PleCCc-EYFP targets to the flagellated pole in C. crescentus (Lam et al., 2003) and can function in place of PleCSm, we were unable to detect its localization in S. meliloti.

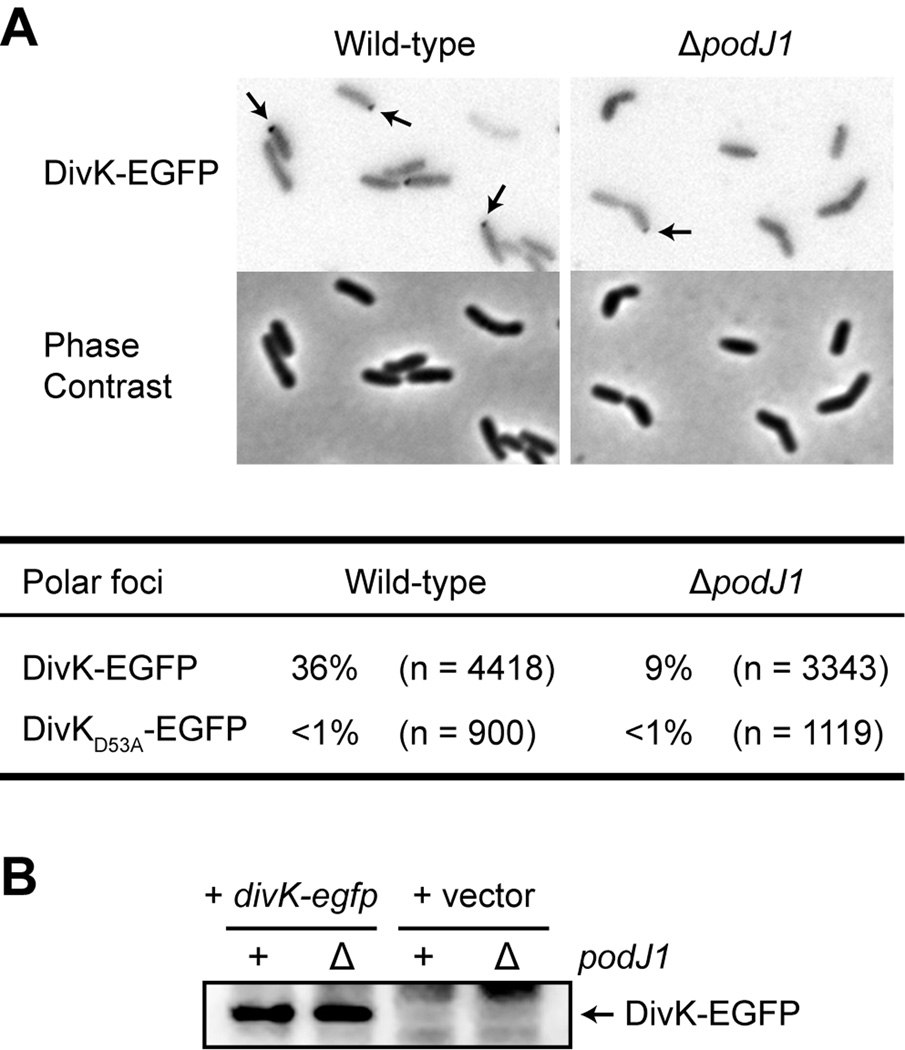

PodJ1 is required for efficient polar localization of DivK

Extensive studies have demonstrated that PleC and DivK act as key components of a regulatory circuit that drives asymmetric cell fates in C. crescentus (Lam et al., 2003; Matroule et al., 2004; Paul et al., 2008; Tsokos et al., 2011). Furthermore, in S. meliloti, DivK (encoded by SMc01371) exhibits a dynamic, polar localization pattern that indicates distinct protein activities in the two progeny cells following division (Lam et al., 2003): DivK accumulates at the old pole in the predivisional cell, such that upon cytokinesis one progeny (the mother cell) retains polarly localized DivK, while the other progeny (the daughter cell) displays uniform distribution of the protein. Postulating that PodJ1 contributes to the regulation of asymmetric division and thus DivK activity in S. meliloti, we examined the dependence of DivK localization on PodJ1. A clear reduction in the polar sequestration of DivK was observed in the absence of PodJ1: 36% of wild-type cells (n = 4418) expressing DivK-EGFP from the pMR20 plasmid displayed fluorescent foci at one pole, compared to 9% in the ΔpodJ1 mutant (n = 3343) (Fig. 7A). Immunoblot analysis indicated that DivK-EGFP was expressed at similar levels in both the wild-type and mutant cells (Fig. 7B). Also, as previously reported (Lam et al., 2003), cells expressing DivKD53A-EGFP, in which the phosphorylatable Asp53 residue of the conserved response regulator has been converted to Ala, did not exhibit any polar localization. Therefore, the ΔpodJ1 mutation appears to disrupt the PleC-DivK signaling system in S. meliloti, resulting in poor DivK localization.

Fig. 7.