Abstract

In Helicobacter pylori, iron balance is controlled by the Ferric uptake regulator (Fur), an iron-sensing repressor protein that typically regulates expression of genes implicated in iron transport and storage. Herein, we carried out extensive analysis of Fur-regulated promoters and identified a 7-1-7 motif with dyad symmetry (5’-TAATAATnATTATTA-3’), which functions as the Fur box core sequence of H. pylori. Addition of this sequence to the promoter region of a typically non-Fur regulated gene was sufficient to impose Fur-dependent regulation in vivo. Moreover, mutation of this sequence within Fur-controlled promoters negated regulation. Analysis of the H. pylori chromosome for the occurrence of the Fur box established the existence of well-conserved Fur-boxes in the promoters of numerous known Fur-regulated genes, and revealed novel putative Fur targets. Transcriptional analysis of the new candidate genes demonstrated Fur-dependent repression of HPG27_51, HPG27_52, HPG27_199, HPG27_445, HPG27_825 and HPG27_1063, as well as Fur-mediated activation of the cytotoxin associated gene A, cagA (HPG27_507). Furthermore, electrophoretic mobility shift assays confirmed specific binding of Fur to the promoters of each of these genes. Future experiments will determine whether loss of Fur regulation of any of these particular genes contributes to the defects in colonization exhibited by the H. pylori fur mutant.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, ferric uptake regulator, Fur box, Fur operator, Fur regulation

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori is arguably one of the most successful pathogens, colonizing the stomachs of about fifty percent of the human population. H. pylori infections lead to very diverse pathologies, which range from gastritis or peptic ulcers to gastric adenocarcinoma and MALT lymphoma (Asaka et al., 1994; Forman, 1996); H. pylori is currently the only known cancer-causing bacterium. Among the most relevant assets of this singular microorganism is its extraordinary ability to adapt, which allows it to withstand the harsh environment characteristic of the stomach lumen. In this sense, while neutrophilic H. pylori cells struggle to traverse the mucus layer to reach the stomach epithelium, they manage to survive in acidic pHs that can be as low as two. Successful adaptation to such a dynamic niche demands sophisticated machineries to sense and rapidly respond to the fluctuating conditions. Typically, transcriptional regulators operate as intracellular sensors that actively contribute to such adaptability by activating and/or silencing specific sets of genes. Intriguingly, H. pylori displays a limited repertoire of transcriptional regulators and encodes for only three sigma factors (Tomb et al., 1997). As expected, some of these transcriptional regulators have been shown to control gene expression in response to acid, as is the case for the metal-responsive transcription factors NikR and Fur (Bury-Mone et al., 2004; Gancz et al., 2006; van Vliet et al., 2004), and the ArsRS two-component system (Pflock et al., 2005; Pflock et al., 2006b).

Maintaining ion balance is another major challenge that H. pylori encounters when colonizing the digestive tract. Indeed, the fundamental role of metal cations as co-factors in many metabolic processes justifies the presence of several ion-responsive regulatory systems in H. pylori. Since iron is essential for virtually all organisms, regulation of intracellular iron homeostasis has become commonplace in all type of cells. Remarkably, bioavailability of iron depends on the oxidation state, which in turn is affected by pH (Braun et al., 1998). In H. pylori iron homeostasis is mediated by Fur, which is an iron-sensing repressor protein that controls the expression of genes implicated in iron transport and storage. The Fur family of metalloregulators includes sensors of iron (Fur), zinc (Zur), manganese (Mur), nickel (Nur) and peroxide stress (PerR), among others (Lee and Helmann, 2007). However, none of these other family members are encoded in H. pylori and thus, it appears that Fur acts as a global regulator, playing a central role in adaptation to multiple stresses such as acid, iron and reactive oxygen species (de Vries et al., 2001). Therefore, the identification of the genes that are subject to Fur regulation is fundamental in order to understand the basics of H. pylori adaptability.

Moreover, as Fur-regulated genes often encode important virulence factors, their identification contributes to the understanding of bacterial pathogenicity (Delany et al., 2004; Johnson et al., 2011). In this sense, expression of recognized virulence genes, such as the Shiga-like toxin from Escherichia coli or several immunomodulatory proteins and cytolysins from Staphylococcus aureus, have been shown to be influenced by Fur (Calderwood and Mekalanos, 1987; Torres et al., 2010). Similarly, the expression of the vacuolating cytotoxin A (vacA) was found to be altered in an H. pylori fur mutant (Gancz et al., 2006; Szczebara et al., 1999). Therefore, it is perhaps not surprising that fur deletion in H. pylori is associated with a delay in the development of and severity of inflammation and pathology in the gastric mucosa of infected animals (Gancz et al., 2006; Miles et al., 2010b). The observed phenotype is probably due to the loss of Fur regulation of genes that are important for early stages of colonization. Reinforcing this assumption, Fur-repressed genes, such as the ferritin pfr, have been shown to be of pivotal importance for colonization (Waidner et al., 2002). It is reasonable, however, that other genes in the Fur regulon, some of them still unidentified, will be similarly implicated in this process.

Current interpretations of the DNA sequences targeted by HpFur are vague, and the exact sequence targeted by HpFur remains obscure, which in turn hinders the identification of novel Fur targets. The first putative target site for Fur (5’-AATAATNNTNA-3’) was identified based on sequence alignment of the promoter regions of several genes induced upon iron starvation (Merrell et al., 2003). Later, a second study proposed that HpFur actually recognizes a sextuplet of the trinucleotide (nAT), which in fact comprises the binding site anticipated by the earlier study (Ernst et al., 2005). Yet, none of the proposed Fur boxes has been validated empirically.

Conversely, the binding sites for Fur in reference bacteria such as E. coli and Bacillus subtilis are much better defined. Pioneering studies pointed out that EcFur binds to a 19-bp region (5’-GATAATGATnATCATTATC-3’) comprising two 9-bp inverted repeats separated by one unmatched nucleotide (de Lorenzo et al., 1987). More recently, Baichoo and Helmann reinterpreted the Fur box as two overlapping 7-1-7 repeats and demonstrated that the sequence 5’-TGATAATnATTATCA-3’ constitutes the minimal unit for BsFur recognition (Baichoo and Helmann, 2002). Interestingly, two overlapping 7-1-7 motifs separated by 6 nucleotides generate an operator containing the two 9-bp inverted repeats introduced earlier by de Lorenzo (5’-TGATAATGATaATCATTATCA-3’). Based on this observation, several reports have suggested that some Fur binding sites are actually targeted by two Fur dimers, which bind on different faces of the DNA helix (Pohl et al., 2003). Interestingly, several reports have shown that Fur polymerizes at the binding site, introducing the idea that sequences neighboring the core Fur box may be important to recruit supplementary Fur molecules to the initial binding site (Delany et al., 2002; Le Cam et al., 1994).

Herein, we describe the identification of a 7-1-7 motif resembling the Fur box from E. coli that is necessary and sufficient to impose Fur regulation in H. pylori. Moreover, in contrast to the previous putative H. pylori target sequences, the Fur box identified here was successfully employed as a template for bioinformatic analyses to identify promoters from known, as well as novel, Fur-regulated genes.

RESULTS

Presence of Fur box-like sequences within high affinity binding sites for HpFur

Expression of genes involved in iron acquisition is typically controlled by Fur. Accordingly, several reports have demonstrated that transcription of fecA1 (HPG27_643), fecA2 (HPG27_763) and frpB1 (HPG27_830) is repressed by iron-bound Fur in H. pylori (Danielli et al., 2009; Delany et al., 2001; Ernst et al., 2005; Gancz et al., 2006; van Vliet et al., 2002). The promoter regions of these three genes have been extensively analyzed, allowing the identification of their respective transcriptional start points as well as the nucleotides protected by Fur in DNase I footprinting assays (Figure 1A). HpFur binds with high affinity to a single operator in the fecA1 promoter and full protection is observed upon the addition of 18nM of Fur dimer (Danielli et al., 2009). The fecA2 promoter holds two high affinity sites for HpFur, which are protected upon the addition of 6 nM and 18 nM of Fur dimer, respectively (Danielli et al., 2009). Finally, Fur binds to two different sites within the frpB1 promoter: operator I, targeted by HpFur with high affinity, and operator II, where HpFur binds with a much lower affinity (Delany et al., 2001). Yet, despite the evident efforts to study Fur-dependent regulation, the exact sequence recognized by HpFur has not been pinpointed.

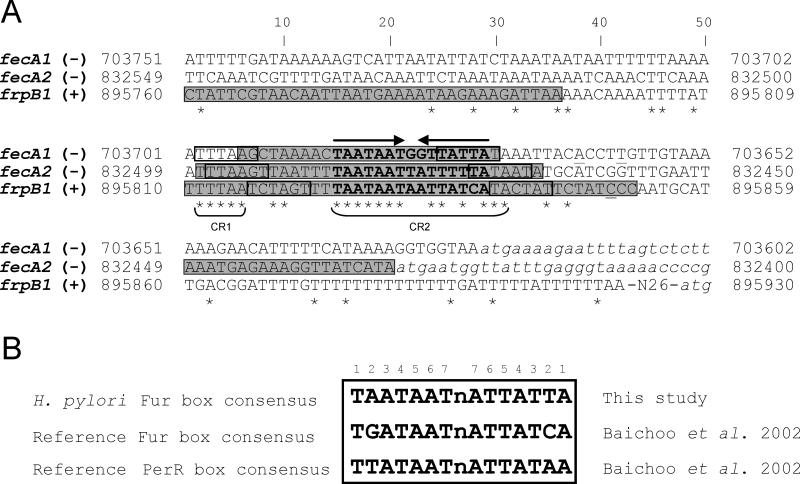

Figure 1.

Sequence analysis of the promoter regions of fecA1 (HPG27_643), fecA2 (HPG27_763) and frpB1 (HPG27_830). A) Sequence alignment generated using ClustalX (Larkin et al., 2007). The asterisks denote fully conserved nucleotides. Underlined nucleotides correspond to the transcriptional start points identified in previous studies (Danielli et al., 2009; Delany et al., 2001), and the predicted -10 and -35 elements are boxed. The gray boxes indicate the regions protected by HpFur in DNase I footprinting assays (Danielli et al., 2009; Delany et al., 2001). CR1 and CR2 represent two well conserved regions (CR). The arrows highlight the presence of an imperfect 7-1-7 inverted repeat with dyad symmetry within the promoter sequences. Nucleotides encompassing this palindromic motif are shown in bold. Sequences shown in lower case correspond to the 5’ ends of the coding regions. The symbols (+) and (-) denote the DNA strand shown. B) Comparison of the Fur box consensus of H. pylori, the reference Fur box and the PerR box consensus.

Sequence alignment of the promoters of fecA1, fecA2 and frpB1 revealed the presence of two well-conserved regions: CR1, located approximately 35 bp upstream from the respective transcriptional start points, and CR2, found in the vicinity of the predicted -10 elements (Figure 1A). Of note, CR2 generates a consensus sequence containing a 7-1-7 inverted repeat with dyad symmetry (5’-TAATAATnATTATTA-3’), which is a classical arrangement of the operators targeted by transcriptional regulators of the Fur family. Indeed, the palindromic sequence found within CR2 depicts a remarkable similarity with the 7-1-7 motif that comprises the basic unit for Fur recognition in B. subtilis, hereafter designated as the reference Fur box (Baichoo and Helmann, 2002). These features suggest that the heptameric repeat may constitute the actual target for HpFur (Figure 1B) and consistent with this idea, the segments of these three promoters that encompass the Fur box-like sequences are targeted by HpFur with high affinity (Danielli et al., 2009; Delany et al., 2001) (Figure 1A).

Conversely, operators targeted by HpFur with low affinity seem to be devoid of well conserved 7-1-7 motifs akin to the reference Fur box. Indeed, preliminary inspection of Fur target sites present in the promoters of exbB2 (HPG27_1287), nikR (HPG27_1286) and ceuE1 (HPG27_1499), did not reveal any apparent Fur box sequence (Delany et al., 2001; Delany et al., 2005). HpFur binds to the promoters of these genes with very low affinity; full protection of the exbB2 and nikR operators is only achieved upon the addition of 165 nM and 500 nM of metal-bound Fur, respectively (Delany et al., 2001; Delany et al., 2005). Thus, it appears that HpFur binds preferably and more avidly to operators containing the 7-1-7 inverted repeat identified here.

Analysis of Fur regulation of target promoters using a gene reporter system

The apparent difference in Fur binding to target promoters prompted us to evaluate Fur regulation in promoters containing either high affinity binding sites (strong sites) or low affinity binding sites (weak sites) for Fur. Since changes in gene expression in H. pylori can be successfully monitored using a gene reporter system based on the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat) gene from E. coli (Bijlsma et al., 2002; Loh et al., 2004; Loh et al., 2007), we constructed transcriptional fusions of PfecA1, PfecA2, PfrpB1, PexbB2 and PnikR to cat. To emphasize the expected participation of the proposed Fur boxes present in the promoters of fecA1, fecA2 and frpB1 in the regulatory process, we utilized short promoter segments (42 bp long) that encompass the predicted -35 and -10 elements, as well as the 7-1-7 inverted repeat (Figure 2A). For the construction of PnikR::cat and PexbB2::cat fusions we also utilized short promoter versions that were devoid of apparent Fur box sequences, but included the entire previously footprinted areas (Delany et al., 2005) (Figure 2A). Each of the generated transcriptional fusions were cloned into plasmid pTM117 (Carpenter et al., 2007) and delivered in trans into the wild type (WT) strain and a Δfur mutant (DSM925) strain.

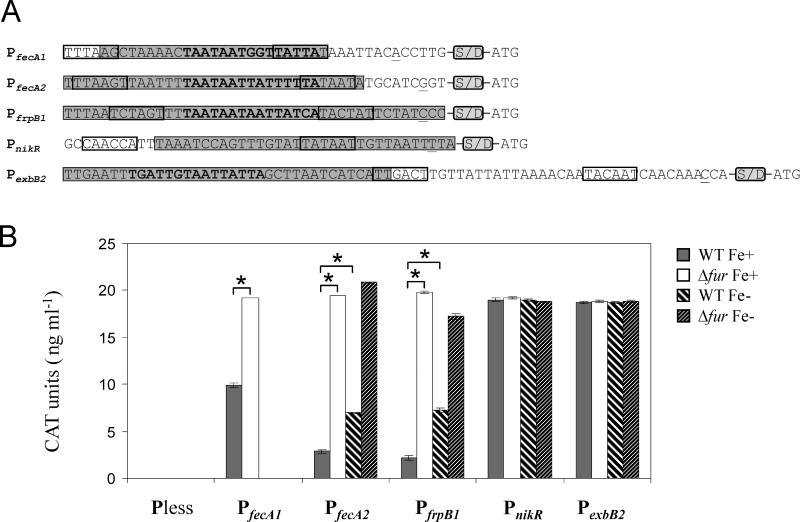

Figure 2.

Analysis of Fur regulation of the promoters of fecA1 (HPG27_643), fecA2 (HPG27_763), frpB1 (HPG27_830), nikR (HPG27_1286) and exbB2 (HPG27_1287) using a gene reporter system. A) Promoter sequences that were fused to the cat coding region to create the aimed transcriptional fusions. Underlined nucleotides correspond to the transcriptional start points identified in previous studies (Danielli et al., 2009; Delany et al., 2001; Delany et al., 2005), and the predicted -10 and -35 elements are boxed. The gray boxes indicate the regions protected by HpFur in DNase I footprinting assays (Danielli et al., 2009; Delany et al., 2001; Delany et al., 2005). Nucleotides encompassing the putative Fur boxes are shown in bold. The presence of the Shine Dalgarno sequence downstream of the promoter sequences is indicated by the acronym S/D. The ATG at the 3’ end of the promoter sequences corresponds to the cat translational start point. B) Analysis of CAT expression from the target transcriptional fusions in the WT and Δfur backgrounds under iron-replete (Fe+) and iron-limited conditions (Fe-). Data shown correspond to a single representative experiment in which CAT units were measured in triplicate. Errors bars represent the standard deviation. Asterisks indicate a significant difference in CAT expression in the Δfur mutant Fe+ or the WT strain Fe- when compared to the WT strain Fe+ (p < 0.01, Student's t-test).

As expected, neither the WT strain nor the Δfur mutant expressed CAT when transformed with pTM117 carrying the promoterless cat construct (Figure 2B). However, CAT expression was clearly detected in the strains carrying the five promoter::cat fusions under study. In keeping with the predicted role of Fur as a repressor, the constructs carrying the promoters of fecA1, fecA2 and frpB1 produced higher levels of CAT in the Δfur background than in the WT strain when grown under iron-replete conditions (Figure 2B and Table 1). The observed decrease in CAT expression in the presence of HpFur clearly demonstrates the presence of a Fur target within the employed streamlined promoters. Moreover, in agreement with the role of iron as a co-repressor, growth of the G27 transformants carrying PfecA2::cat o r PfrpB1::cat under iron-limited conditions increased CAT expression 2.45- and 3.24-fold, respectively (Figure 2B).

Table 1.

Fold change in CAT expression observed in two representative experiments

| Fold change (Δfur-Fe+/WT-Fe+) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Promoter | Experiment 1 | Experiment 2 |

| None | ND | ND |

| fecA1 | 1.84 | 1.93 |

| fecA2 | 8.46 | 6.83 |

| frpB1 | 9.12 | 7.67 |

| nikR | 1.01 | 1.01 |

| exbB2 | 0.99 | 1.01 |

| pdxJ | 6.69 | 6.55 |

| pdxJ(mut) | 1.30 | 1.12 |

| amiE | 12.28 | 9.67 |

| amiE(-) | 0.61 | 0.59 |

| hpn2 | 1.76 | 1.89 |

| hpn2(-) | 1.12 | 1.02 |

| ribBA | 0.33 | 0.34 |

| ribBA(-) | 0.99 | 1.02 |

| babB | 1.01 | 0.99 |

| babB+10 | 1.10 | 1.00 |

| babB -4 | 6.51 | 6.89 |

| babB -19 | 8.21 | 9.49 |

| babB -23 | 2.35 | 2.82 |

| babB -43 | 4.77 | 4.95 |

| babB -60 | 1.07 | 0.99 |

| babB -100 | 1.05 | 1.08 |

| babB -140 | 1.03 | 1.04 |

| babBFur-23 | 34.9 | 19.31 |

| babBPerR-23 | 2.73 | 2.98 |

Changes in CAT expression above 1.8-fold are shown in bold

ND, not detected

(mut) indicates that the promoter carries a mutated Fur box

(-) indicates that the Fur box has been deleted in the promoter

Conversely, no difference in CAT expression was observed between the WT strain and the Δfur mutants carrying the low affinity fusions PnikR::cat or PexbB2::cat (Figure 2B and Table 1). Furthermore, iron deprivation had no impact on CAT expression in these strains. Therefore, the presence of a binding site for Fur in the nikR and the exbB2 promoters could not be validated using our CAT reporter system. Additional analyses will be required to test whether the presence of low affinity binding sites for HpFur in the promoters of nikR and the exbB2 are sufficient to support Fur regulation.

Occurrence of the proposed Fur box in the chromosome of strain G27

The presence of the proposed Fur box (5’-TAATAATnATTATTA-3’) in the genome of G27 was screened for using Genamics Expression Software (www.genamics.com). The exact consensus sequence was not found anywhere in the chromosome and therefore, we sought to identify sequences similar to the proposed Fur box consensus. Since the Fur box proposed here is still poorly understood and the relative importance of each residue is unknown, we applied a high-stringency filter and looked for sequences with no more than two mismatches with respect to the consensus (homology >85%) in order to increase the likelihood of identification of bona fide Fur boxes. Moreover, though several coding regions were found to contain putative Fur boxes, we focused on motifs located within intergenic regions (Table 2). A total of eighteen unique intergenic regions were identified: six containing putative Fur boxes that showed a single mismatch with respect to the consensus, and twelve that showed sequences with two mismatches. As expected, our search confirmed the presence of Fur box sequences within the intergenic regions harboring the promoters of fecA1, fecA2 and frpB1. In addition, we found a Fur box in the promoter region of the fur locus (HPG27_401), which has been shown to be autoregulatory (Delany et al., 2002). Of note, this Fur box was located inside operator I, which is targeted by HpFur with very high affinity. The fur promoter region was investigated in detail in a previous report, revealing an exceptionally intricate mechanism of Fur regulation (Delany et al., 2003). Candidate Fur boxes were also found in the intergenic regions containing the promoters of amiE (HPG27_273) and hpn2 (HPG27_1353), encoding an aliphatic amidase (van Vliet et al., 2003) and a histidine- and glutamine-rich protein involved in nickel storage and iron detoxification (Seshadri et al., 2007), respectively. Notably, both genes have been shown to be subject to Fur regulation in previous transcriptome analysis of H. pylori (Ernst et al., 2005; Gancz et al., 2006). Although the promoters of amiE and hpn2 have not yet been footprinted in the presence of HpFur, electrophoretic mobility shift assays have demonstrated binding of the metalloregulator to their corresponding DNA sequences (Dian et al., ; Ernst et al., 2005; Gancz et al., 2006).

Table 2.

Ocurrence of Fur box-like sequences in the chromosome of G27

| Intergenic regions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position† | Fur box sequence* | Mismatches¶ | Genes flanking this region§ | Locus# | |

| 1. | 62565 | TAATAATGCTTTTTA | 2/15 | HPG27_51 (-) / HPG27_52 (+) | putA/HP |

| 2. | 222796 | GAATAATCATTTTTA | 2/15 | HPG27_199 (-) / HPG27_200 (+) | HP |

| 3. | 306594 | TAATCATAATAATTA | 2/15 | HPG27_272 (+) / HPG27_273 (+) | amiE |

| 4. | 430480 | TAAAACTCATTATTA | 2/15 | HPG27_401 (-) / HPG27_402 (-) | fur |

| 5. | 477843 | TAATTATTATTTTTA | 2/15 | HPG27_444 (-) / HPG27_445 (+) | hofC |

| 6. | 548097 | TATTAATAATGATTA | 2/15 | HPG27_506 (-) / HPG27_507 (+) | cagA |

| 548100 | TAATAATGATTAATG | 2/15 | HPG27_506 (-) / HPG27_507 (+) | cagA | |

| 7. | 636770 | TTATTATTATTATTA | 2/15 | HPG27_582 (-) / HPG27_583 (-) | |

| 636773 | TTATTATTATTATTA | 2/15 | HPG27_582 (-) / HPG27_583 (-) | ||

| 636776 | TTATTATTATTATTA | 2/15 | HPG27_582 (-) / HPG27_583 (-) | ||

| 8. | 703673 | TAATAACCATTATTA | 1/15 | HPG27_643 (-) / HPG27_644 (-) | fecA1 |

| 9. | 828366 | TAATAACGATTATTA | 1/15 | HPG27_760 (-) / HPG27_761 (-) | ribBA |

| 10. | 832471 | TAAAAATAATTATTA | 1/15 | HPG27_763 (-) / HPG27_764 (-) | fecA2 |

| 11. | 834782 | TATTATTAATTATTA | 2/15 | HPG27_767 (-) / HPG27_768 (-) | |

| 834785 | TATTAATTATTATTA | 1/15 | HPG27_767 (-) / HPG27_768 (-) | ||

| 12. | 892111 | TAATCATTATAATTA | 2/15 | HPG27_825 (-) / HPG27_826 (+) | cdh |

| 13. | 895824 | TAATAATAATTATCA | 1/15 | HPG27_829 (-) / HPG27_830 (+) | frpB1 |

| 14. | 1169453 | CAATAATCGTTATTA | 2/15 | HPG27_1063 (-) / HPG27_1064 (-) | ggt |

| 15. | 1465943 | TAAAAATTAGTATTA | 2/15 | HPG27_1352 (-) / HPG27_1353 (+) | hpn2 |

| 16. | 1571800 | TAATAATAATTAGTA | 1/15 | HPG27_1449 (-) / HPG27_1450 (-) | |

| 17. | 1645025 | CAAAAATCATTATTA | 2/15 | HPG27_1518 (-) / HPG27_1519 (+) | pdxJ |

| 18. | 1648219 | TGATAATCATGATTA | 2/15 | HPG27_1521 (+) / HPG27_1522 (+) | |

| Coding regions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position† | Fur box sequence* | Mismatches¶ | Locus_tag | Annotation | |

| 1. | 264689 | TAATAATCCTTATTA | 1/15 | HPG27_239 (-) | type III adenine MTase |

| 2. | 285743 | TAATCATAATTTTTA | 2/15 | HPG27_261 (+) | hypothetical protein |

| 3. | 323622 | TAATAATCTTTCTTA | 2/15 | HPG27_290 (-) | type II restriction enzyme |

| 4. | 389931 | TAAAAATAATTTTTA | 2/15 | HPG27_357 (-) | phosphatidyl serine synthase |

| 5. | 537753 | TAATATAGATTATTA | 2/15 | HPG27_495 (+) | cagM |

| 6. | 545139 | TAATAATAATTCTTC | 2/15 | HPG27_503 (-) | cagE |

| 7. | 588073 | TAATAATCATTTTTA | 1/15 | HPG27_547 (+) | amino deoxy chorismate lyase |

| 8. | 728269 | TACTAATCTTTATTA | 2/15 | HPG27_663 (+) | outer membrane protein (hopE) |

| 9. | 897622 | TAATATTGATTATTC | 2/15 | HPG27_830 (+) | frpB1 |

| 10. | 980666 | AAATATTTATTATTA | 2/15 | HPG27_901 (-) | hypothetical protein |

| 11. | 1001033 | AAATAAGAATTATTA | 2/15 | HPG27_918 (-) | hypothetical protein |

| 12. | 1054951 | TACTAATGATCATTA | 2/15 | HPG27_966 (+) | comB9-like competence protein |

| 13. | 1058383 | TACTAATGATTATTT | 2/15 | HPG27_970 (+) | virB11-like type IV SS ATPase |

| 14. | 1067777 | TCATAATCATCATTA | 2/15 | HPG27_980 (-) | adenine specific DNA MTase |

| 15. | 1536887 | TCATAATGATGATTA | 2/15 | HPG27_1423(+) | type II adenine MTase |

First nucleotide of the Fur box according to the Genbank sequence CP001173

Only the positive strand is shown and the mismatches with respect to the Fur box consensus are indicated in bold

Number of mismatches with respect to the Fur box consensus / Number of residues of the Fur box consensus

Coding strand: (-), negative; (+), positive. Genes found to be Fur-regulated in this study are shown in bold.

Annotation of the Fur-regulated locus according to Baltrus et al. (Baltrus et al., 2009).

SS, secretion system; MTase, methylase

Another Fur box sequence was found in the intergenic region encompassing the promoter of pdxJ (HPG27_1519), which encodes an enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of vitamin B6 (Grubman et al. 2010). Our group previously demonstrated both Fur-dependent expression of pdxJ and Fur binding to the pdxJ promoter (Gancz et al., 2006). The pdxA gene, which is predicted to comprise an operon along with pdxJ, has also been found to be regulated by Fur (Ernst et al., 2005; Gancz et al., 2006). Our search also revealed the presence of a well-conserved Fur box in the intergenic region harboring the promoter of ribBA (HPG27_760), which encodes a bifunctional enzyme catalyzing two essential steps in riboflavin biosynthesis (Worst et al., 1998). A modified Fur titration assay (FURTA-Hp), previously revealed the presence of a binding site for Fur in the promoter of this gene (Fassbinder et al., 2000). Therefore, on the whole, our search for candidate Fur boxes in the genome of G27 allowed the identification of promoters of many genes for which Fur regulation has been well-established. Of note, a similar scan for the E. coli reference Fur box in the genome of G27 only identified one known target for HpFur, the frpB1 promoter; thus, suggesting that the Fur box of H. pylori is similar but different from the Fur box of reference bacteria such as E. coli and B. subtilis.

Finally, in addition to the well-known Fur-regulated genes mentioned above, our screen identified putative Fur boxes in ten intergenic regions flanked by genes for which Fur regulation has not been previously appreciated. Transcription of these candidate novel Fur-regulated genes is described later in the text.

Mutagenesis of Fur-regulated promoters

To conclusively demonstrate the requirement of the proposed Fur box for Fur regulation, we first attempted to mutate the predicted Fur boxes in the promoters of fecA1, fecA2 and frpB1. Mutant promoters carrying nucleotide substitutions located upstream from the -10 element, which was preserved, were created and analyzed for CAT expression. Consistently, CAT expression was barely detectable with the transcriptional fusions tested (data not shown). This result is not unexpected, and is actually in agreement with the accepted notion that transcription in ε-proteobacteria initiates at extended Pribnow boxes downstream of periodic AT-rich stretches (Petersen et al., 2003; Sharma et al., 2010).

Alternatively, the promoter regions of amiE, hpn2, ribBA and pdxJ were subjected to mutagenesis. amiE and hpn2 have previously been shown to be transcribed by the vegetative RNA polymerase and the corresponding -35 and -10 elements have been identified (Danielli et al., 2006; Pflock et al., 2006a). On the other hand, the recently reported transcriptome analysis of H. pylori revealed that the ribBA (HP0804) and pdxJ (HP1582) promoters display extended -10 elements (Sharma et al., 2010), as indicated by the presence of a TGn motif preceding the well-conserved -10 boxes (TACAAT and TATATT, respectively). Primer extensions conducted in our laboratory with strain G27 corroborated this data (data not shown). Noteworthy, E. coli promoters with extended -10 elements do not require the presence of -35 boxes to initiate transcription (Kumar et al., 1993; Sabelnikov et al., 1995). Based on this information, transcriptional fusion of these four promoters to cat were created and moved into H. pylori (Figure 3A).

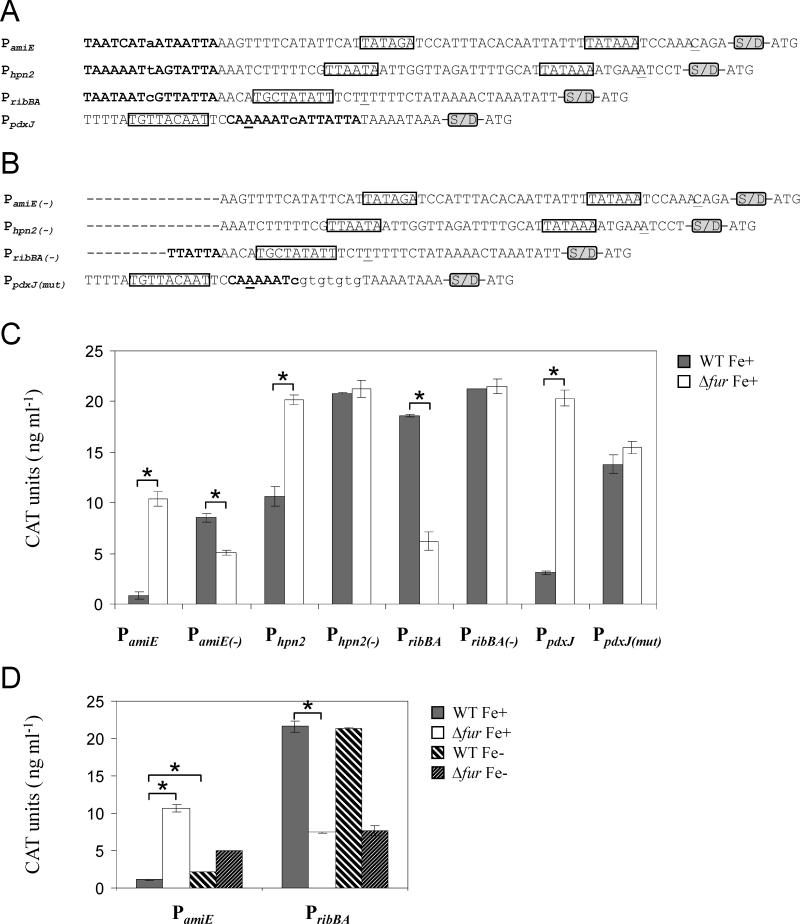

Figure 3.

Analysis of Fur regulation of the promoters of amiE (HPG27_273), hpn2 (HPG27_1353), ribBA (HPG27_760) and pdxJ (HPG27_1519) using a gene reporter system. A) Promoter sequences that were fused to the cat coding region to create the aimed transcriptional fusions. Underlined nucleotides correspond to the transcriptional start points identified in previous studies (Danielli et al., 2006; Pflock et al., 2006a; Sharma et al., 2010), and the predicted -10 and -35 elements are boxed. ribBA and pdxJ display extended -10 elements. The nucleotides encompassing the putative Fur boxes are shown in bold. The presence of the Shine Dalgarno sequence downstream of the promoter sequences is indicated by the acronym S/D. The ATG at the 3’ end of the promoter sequences corresponds to the cat translational start point. B) Promoter sequences used to create the transcriptional fusions in which the Fur box was either deleted or mutated. C) Analysis of CAT expression from the target transcriptional fusions in the WT and Δfur backgrounds under iron-replete (Fe+) conditions. Data shown correspond to a single representative experiment in which CAT units were measured in triplicate. Errors bars represent the standard deviation. Asterisks indicate a significant difference in CAT expression in the Δfur mutant Fe+ when compared to the WT strain Fe+ (p < 0.01, Student's t-test). D) Analysis of CAT expression from PamiE::cat and PribBA::cat in the WT and Δfur backgrounds under iron-replete (Fe+) and iron-limited conditions (Fe-). Data shown correspond to a single representative experiment in which CAT units were measured in triplicate. Errors bars represent the standard deviation. Asterisks indicate a significant difference in CAT expression in the Δfur mutant Fe+ or the WT strain Fe- when compared to the WT strain Fe+ (p < 0.01, Student's t-test).

Our reporter system confirmed the expected role of iron-bound Fur as a repressor of amiE, pdxJ and hpn2 (Figure 3C and Table 1); CAT expression was clearly lower in the WT strain than in the Δfur transformants, though to a different extent for each promoter fusion. In contrast, the absence of Fur consistently prompted a marked reduction of CAT expression when the ribBA promoter was evaluated, suggesting a positive effect of Fur on CAT expression. Regardless of the particular effect of Fur on CAT expression, deletion or mutagenesis of the predicted Fur boxes from all four promoters abrogated Fur-dependent regulation (Figure 3B-C and Table 1).

Since the amiE promoter has been used as a model to study Fur regulation in our laboratory (Carpenter et al., 2007; Carpenter et al., 2010), the effect of iron depletion was also evaluated in the transformant carrying PamiE::cat (Figure 3D). In the presence of Fur, we observed a moderate increase in CAT expression (~2-fold) upon the addition of the iron chelator 2,2'-dipyridyl (DPP), indicative of partial derepression. Of note, CAT levels in the absence of Fur were lower under iron depleted conditions than when iron was present, which suggests that amiE is under the control of another metalloregulator. In agreement with this observation, binding of ArsR~P to the amiE promoter is well-documented (Pflock et al., 2006a). This example certainly illustrates that the in vivo analysis of promoters targeted by multiple regulators may be complex. In keeping with this, the unanticipated phenotype displayed by the transformants carrying PribBA::cat was also investigated further by monitoring CAT expression under iron-limited conditions. To our surprise, the addition of DPP had no impact on CAT expression, suggesting that the phenotype observed was independent of the iron status. This result is unexpected since several reports demonstrated that transcription of ribBA is consistently repressed by iron (Ernst et al., 2005; Merrell et al., 2003; Worst et al., 1998). The mechanism by which Fur activates CAT expression in our PribBA::cat constructs is currently unclear and will require further investigation.

Introduction of a Fur box de novo in the promoter region of a gene not regulated by Fur

In order to test whether the identified Fur box was sufficient to mediate Fur regulation in H. pylori, the perfect consensus sequence was introduced into the promoter region of a gene not typically regulated by Fur. For this purpose, we used the promoter of the babB gene (HP0896), which encodes a member of a paralogous family of H. pylori outer membrane proteins (hop) that undergoes allelic variation and mediates adherence to the ABO and Lewis b (Leb) blood group antigens in the human stomach (Pride et al., 2001). Indeed, babB expression does not appear to be regulated by Fur and accordingly, the promoter region of this adhesin does not possess any putative Fur box (Tomb et al., 1997).

To provide solid evidence that babB expression is not Fur-dependent, we generated a transcriptional fusion of the babB promoter to cat (Figure 4A). Since the promoter sequence TTATGC-19-GATAAG, located immediately upstream from the transcriptional start site, only drives weak expression of the babB locus (Backstrom et al., 2004), we first modified the -10 element to 5’-TATAAT-3’ in order to increase the strength of the promoter. The resulting PbabB::cat fusion was transformed into the WT strain and a Δfur mutant and tested for CAT expression. As expected, CAT levels were found to be similar in both strain backgrounds, indicating that the expression driven by the synthetic babB promoter is Fur-independent (Figure 4B and Table 1). Furthermore, the addition of DPP had no impact on CAT expression. In contrast, the introduction of a perfect Fur box consensus centered at position -19 within the babB promoter (+1 being the transcriptional start point) resulted in marked reduction of CAT expression in the WT background (Figure 4B and Table 1). Consistent with Fur-dependent expression, CAT levels were much higher when this transcriptional fusion was analyzed in a Δfur mutant. In keeping with this observation, the addition of DPP increased CAT expression 4.43-fold in the WT transformants carrying PbabB-19::cat. These results indicate that the introduction of the 7-1-7 inverted repeat de novo is sufficient to induce Fur-dependent regulation of a synthetic promoter in H. pylori.

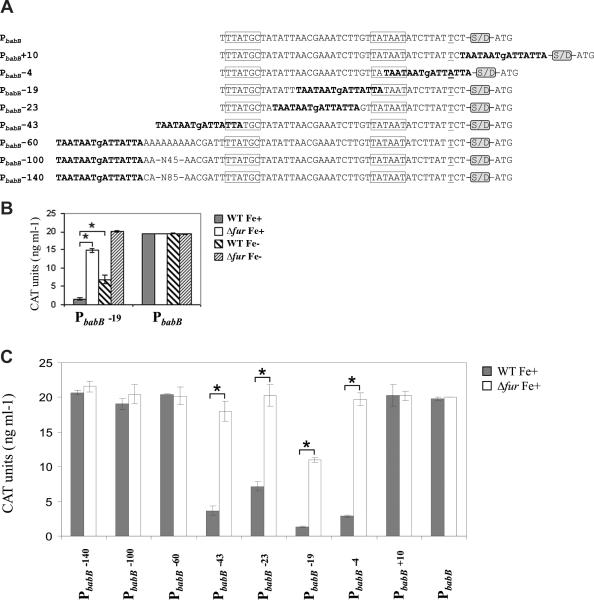

Figure 4.

Analysis of Fur regulation upon the de novo introduction of a Fur box in the promoter region of a gene otherwise non-Fur-regulated. A) babB promoter and derivatives carrying a Fur box consensus at different positions. Underlined nucleotides correspond to the transcriptional start point identified in a previous study (Backstrom et al., 2004), and the predicted -10 and -35 elements are boxed. The presence of the Shine Dalgarno site downstream of the promoter sequences is indicated by the acronym S/D. The ATG at the 3’ end of the promoter sequences corresponds to the cat translational start point. B) Analysis of CAT expression from PbabB::cat and PbabB-19::cat in the WT and Δfur backgrounds under iron-replete (Fe+) and iron-limited conditions (Fe-). Data shown correspond to a single representative experiment in which CAT units were measured in triplicate. Errors bars represent the standard deviation. Asterisks indicate a significant difference in CAT expression in the Δfur mutant Fe+ or the WT strain Fe-when compared to the WT strain Fe+ (p < 0.01, Student's t-test). C) Analysis of CAT expression from the target transcriptional fusions in the WT and Δfur backgrounds under iron-replete (Fe+) conditions. Data shown correspond to a single representative experiment in which CAT units were measured in triplicate. Errors bars represent the standard deviation. Asterisks indicate a significant difference in CAT expression in the Δfur mutant Fe+ when compared to the WT strain Fe+ (p < 0.01, Student's t-test).

In light of this finding, we next wondered about the possible impact of the location of the Fur box on Fur-dependent regulation of the synthetic promoter. To address this question, the 7-1-7 motif was introduced at different positions within the babB promoter and evaluated for Fur-dependent regulation with the CAT reporter system (Figure 4A). We found that Fur boxes centered at positions -4, -23 and -43 were also capable of mediating Fur regulation of CAT, though to different extents in each case (Figure 4C and Table 1). The introduction of a Fur box at position -23, which does not overlap either the -35 or the -10 elements, showed the lowest degree of Fur-dependent repression, whereas Fur boxes centered at positions -4 and -43 led to a marked repression of CAT expression in the presence of the metalloregulator.

In contrast, transcriptional fusions carrying Fur boxes located further upstream in the babB promoter (centered at -60, -100 and -140) did not impart Fur-dependent regulation (Figure 4C and Table 1). Likewise, introduction of a Fur box after the transcriptional start point (centered at +10) did not lead to Fur regulated expression of CAT (Figure 4C and Table 1). Therefore, it appears that only Fur boxes located in proximity to the -35 or -10 boxes are capable of generating Fur-dependent regulation in our synthetic promoter.

HpFur recognizes a reference Fur box consensus and a PerR box consensus

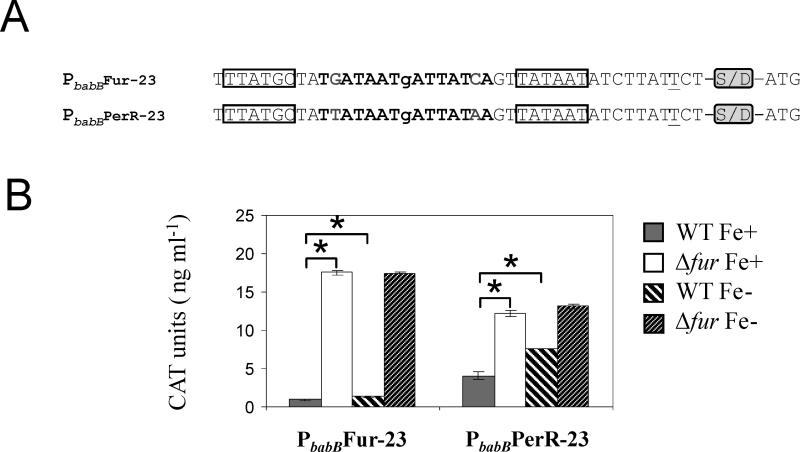

As stated earlier, the Fur box consensus of H. pylori shows a remarkable similarity to the 7-1-7 core constituting the basic unit for Fur recognition in reference bacteria such as B. subtilis and E. coli (Baichoo and Helmann, 2002). Based on this observation, we wondered whether HpFur could actually recognize and regulate a promoter containing this reference Fur box sequence (Figure 1B). To address this question, the heptameric inverted repeat was introduced into the babB promoter centered at position -23 (Figure 5A). This position was chosen in order to preserve the sequence of the -10 and -35 elements in the resulting transcriptional fusion, designated PbabBFur-23::cat.

Figure 5.

Analysis of Fur regulation, upon the de novo introduction of a reference Fur box or a PerR box in the promoter region of a gene otherwise non-Fur-regulated. A) Derivatives of the babB promoter carrying a Fur box or a PerR box consensus centered at position -23 (with respect to the trancriptional start point). Nucleotides underlined correspond to the transcriptional start point identified in a previous study (Backstrom et al., 2004), and the predicted -10 and -35 elements are boxed. The nucleotides encompassing the consensus operators are shown in bold. The presence of the Shine Dalgarno site downstream of the promoter sequences is indicated by the acronym S/D. The ATG at the 3’ end of the promoter sequences corresponds to the cat translational start point. B) Analysis of CAT expression from PbabBFur-23::cat and PbabBPerR-23::cat in the WT and Δfur backgrounds under iron-replete (Fe+) or iron-limited conditions (Fe-). Data shown correspond to a single representative experiment in which CAT units were measured in triplicate. Errors bars represent the standard deviation. Asterisks indicate a significant difference in CAT expression between in the Δfur mutant Fe+ or the WT strain Fe- when compared to the WT strain Fe+ (p < 0.01, Student's t-test).

We determined that CAT expression was markedly repressed in the WT background, indicating that HpFur recognizes the reference Fur box (Figure 5B and Table 1). This result is perhaps not surprising since it has been previously shown that HpFur can partially complement a fur negative mutant of E. coli (Bereswill et al., 1999). Furthermore, heterelogous expression of HpFur in E. coli proficiently regulates lacZ expression driven by the promoters of fiu and fhuF, two known Fur-regulated genes in E. coli (Bereswill et al., 1999; Fassbinder et al., 2000). Noteworthy, CAT expression became tightly regulated by Fur in the WT transformant carrying PbabBFur-23::cat; the observed fold change in CAT expression was much higher than that of the PbabB-23::cat fusion harboring the HpFur box consensus in the same position. Intriguingly, in the presence of Fur, iron limitation never led to an increase in CAT expression above 1.45-fold.

In parallel, we investigated whether HpFur could also recognize the operator of another metalloregulator of the Fur family, the peroxide stress regulator PerR (Bsat et al., 1998). The DNA target sequence of PerR is also a 7-1-7 in verted repeat (5’-TTATAATNATTATAA-3’) identical to the HpFur box consensus at six of the seven defined positions (Figure 1B) (Baichoo and Helmann, 2002). A transcriptional fusion carrying the PerR box consensus, designated PbabBPerR-23::cat, was found to also be regulated by HpFur (Figure 5B and Table 1). In this case, the extent of Fur repression was similar to that observed for the PbabB-23::cat fusion, and CAT expression was responsive to iron limitation. Thus, in contrast to Fur proteins from other bacteria, it appears that HpFur targets the consensus operators of these two paralogs in vivo (Fuangthong and Helmann, 2003).

Identification of new genes regulated by Fur

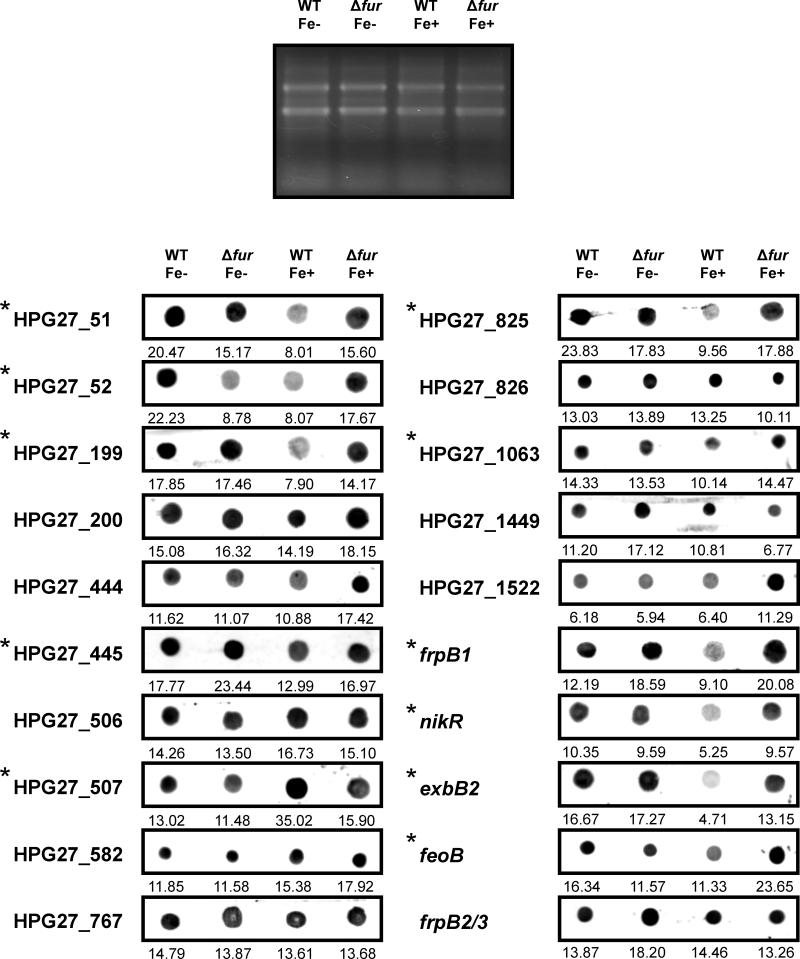

As discussed earlier, our scan of the G27 genome for conserved Fur boxes allowed the identification of ten intergenic regions flanked by genes for which Fur regulation was not previously appreciated. The effect of Fur on transcription of these genes was investigated by RNA dot blot hybridization. Five out of the ten intergenic regions with putative Fur-boxes under study were flanked by two divergently transcribed genes. In this case, both divergent transcriptional units constitute possible candidates for Fur regulation and thus, a total of fifteen genes were investigated. Six of the novel genes evaluated were repressed by iron-bound Fur as indicated by decreased expression in the WT strain in iron-replete conditions, and increased expression upon iron-depletion and fur deletion (Figure 6). Of these six genes, HPG27_51, HPG27_52, HPG27_199 and HPG27_825 were strongly repressed by metal-bound Fur and HPG27_445 and HPG27_1063 were weakly Fur-regulated. Decreased detection of the HPG27_52 transcript in the absence of Fur and iron suggests that this gene is also under the control of another metalloregulator. According to the annotation by Baltrus et. al., these genes encode: a proline/delta1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase (HPG27_51), a hypothetical protein (HPG27_52), a phospholipid-binding protein (HPG27_199), an outer membrane protein (HPG27-445), a CDP-diglyceride hydrolase (HPG27_825) and a gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (HPG27-1063) (Baltrus et al., 2009). In addition to the novel Fur-repressed genes, our transcriptional analysis also revealed that expression of the cytotoxin associated gene A, cagA (HPG27_507), was upregulated in the WT strain in iron-replete conditions in a Fur-dependent manner. This finding is consistent with metal-bound Fur acting as an activator of cagA transcription. Altogether, these results are compatible with the presence of functional Fur boxes in six out of the ten novel intergenic regions examined here (Figure 6, genes indicated with asterisks). Therefore, en masse, fourteen out of the eighteen unique intergenic regions encompassing candidate Fur boxes are adjacent to a proven Fur-regulated gene (Table 2). For the remaining intergenic regions, we cannot rule out that some of the adjacent genes that appear to be constitutively expressed in our analysis become Fur-regulated under specific conditions.

Figure 6.

Transcriptional analysis of target genes from H. pylori strain G27 by RNA dot blot. DNA probes specific for the 20 target genes were generated and hybridized to 2.5 μg of RNA purified from the WT and Δfur mutant strains exposed to iron-replete (+Fe) and iron-depleted conditions (Fe-). The asterisks denote Fur-regulated genes. On the top, an agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide shows equal amounts of RNA per sample. The values below the blots show the result of the densitometric image analysis using Multi-Gauge software.

In parallel, Fur regulation of five other genes, frpB1, exbB2, nikR, frpB2/3 (HPG27_866) and feoB (HPG27_644), was also investigated by RNA dot blot hybridization. Expression of frpB1, exbB2, nikR and feoB was found to be visibly repressed by Fur in the presence of iron (Figure 6). Fur regulation of exbB2 and nikR was not supported by our CAT reporter system (Figure 2). However, as only short fragments of the exbB2 and nikR promoters were used to obtain the corresponding transcriptional fusions, additional sequences absent in our reporter system might be required in order for Fur regulation of these genes to be effective. Finally, we found that frpB2/3 transcription was not subject to Fur regulation, demonstrating that Fur-dependent expression of particular genes is not always conserved across H. pylori strains; frpB2/3 was found to be repressed by metal-bound Fur in strain 26695 (van Vliet et al., 2002).

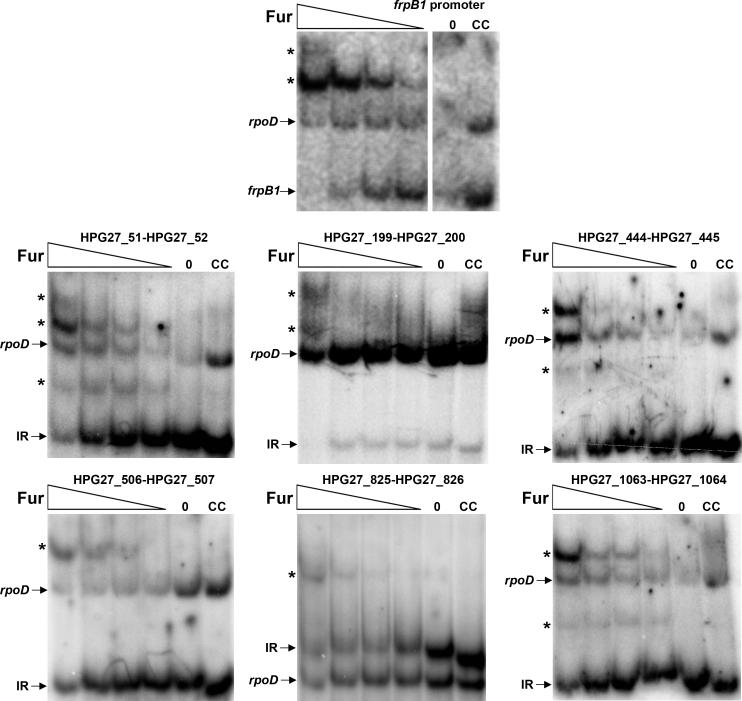

HpFur binds to the promoters of the novel Fur regulated genes

To confirm that HpFur was able to specifically bind the Fur box containing regions upstream of the newly identified targets, we purified the regulatory protein and analyzed binding via EMSA (Electrophoretic mobility shift assay). We found that the addition of increasing concentrations of the metalloregulator resulted in a change in migration of the six DNA fragments corresponding to the intergenic regions encompassing the candidate Fur boxes. In contrast, no appreciable change was observed in the migration of the rpoD promoter, which was included in each reaction as a negative control (Figure 7). These results strongly support our genetic data that indicate that HpFur targets the proposed Fur boxes and directly regulates the newly identified target genes.

Figure 7.

Analysis of HpFur binding to the promoters of the newly identified Fur-regulated genes by EMSA. Equal amounts of end-labeled fragments for each individual intergenic region (IR) and the rpoD promoter (negative control) were mixed and incubated with increasing Fur concentrations (0, 14.8, 37, 74 and 148 ng ml-1). The addition of HpFur shifts the frpB1 promoter (positive control) as well as the intergenic DNA fragments analyzed. The shifted fragments are indicated by asterisks. The specificity of the reaction is shown by the addition of excess unlabeled IR DNA (CC lane), which shifts the IR region back to the normal migration position even in the presence of 148 ng ml-1 of Fur. A gel containing extended HpFur concentrations was run for frpB1. However, HpFur concentrations below 14.8 ng ml-1 were unable to shift the frpB1 promoter and the corresponding lanes have been removed from the image for uniformity and better clarity.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we carried out a comprehensive analysis of Fur-regulated promoters of H. pylori using an in vivo strategy. As a result, we identified a 7-1-7 motif with dyad symmetry as the Fur box core sequence of this bacterium. This finding is supported by multiple lines of evidence: i) this motif is present in the promoter region of numerous genes previously shown to be regulated by Fur, ii) deletion or mutation of this motif from the promoter of known Fur-regulated genes abrogates Fur regulation, iii) the introduction of this motif in a promoter otherwise non-regulated by Fur induces Fur-dependent regulation, and iv) a search for this motif in the genome of G27 allowed the identification of novel genes under the control of Fur. The palindromic structure of the HpFur operator identified in this study is in compliance with the current working model that supports metal-bound Fur interaction with DNA as a dimer (Pohl et al., 2003). According to this model, each Fur monomer interacts with one half of the DNA primary target comprised basically of seven nucleotides.

A comparison of the identified HpFur operator to the heptameric inverted repeat representing the reference Fur box (Baichoo and Helmann, 2002), revealed that up to six out of the seven defined positions from both operators are identical (Figure 1B). The substitution of guanine to adenine in position two in H. pylori likely reflects the high A/T content of the H. pylori genome. Moreover, this nucleotide change might be responsible for the failure of Fur from different bacteria to fully complement an H. pylori fur mutant (Miles et al., 2010a). That is, it is possible that this nucleotide substitution prevents efficient binding of heterologous Fur proteins to HpFur targets. Such a critical role for the second nucleotide of the heptameric repeat is not unexpected. On the contrary, it has been shown that this particular position of the heptamer is critical for B. subtilis to discriminate between Fur, PerR and Zur targets (Fuangthong and Helmann, 2003). To this end, BsFur does not bind to promoters containing a BsPerR box, which differs from the Fur box only at position two of the repeat (Figure 1B). This discrimination is essential in order to preserve the functional autonomy of the Fur and PerR regulons and accordingly, no naturally occurring sites are known that are subject to dual regulation by BsFur and BsPerR. Conversely, our results show that HpFur efficiently recognizes a BsFur box as well as a BsPerR box in vivo (Figures 4 and 5). Thus, it is tempting to speculate that the absence of other regulators of the Fur family such as PerR, Zur or Mur in H. pylori, relieves the metalloregulator from a rigorous selective pressure for the operator. In consequence, HpFur appears to be more promiscuous than Fur proteins from other bacteria.

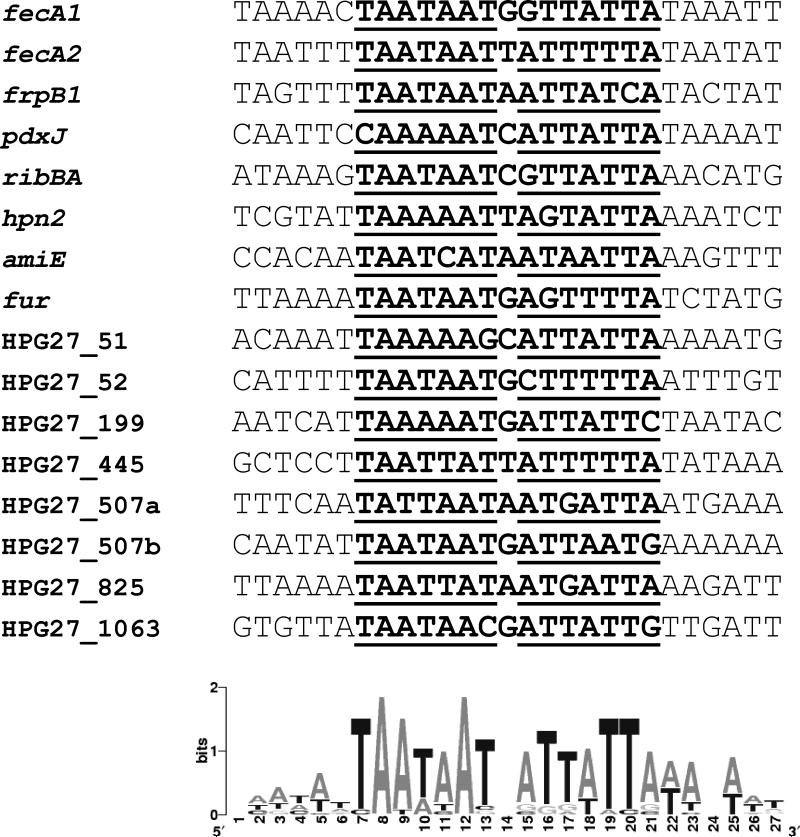

Previous reports have shown that Fur often binds to extended regions flanking the 7-1-7 core (Chen et al., 2007). These extensions may either facilitate Fur interaction with the target DNA or encourage oligomerization of Fur at the target site (Delany et al., 2002). In Yersinia pestis for instance, Fur binds to a 19-bp operator consisting of the 7-1-7 core flanked by the dinucleotide AA at the 5’ end and TT at the 3’ end (Gao et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2006). Similarly, recent DNA sequence alignments indicate that Zur also binds to DNA targets with a similar 7-1-7 core, but with a 3-bp extension on both sides (Gaballa et al., 2002). The sequence logo generated for all the functional Fur operators of H. pylori identified in this study does not support the presence of well-conserved symmetrical extensions adjacent to the core Fur box (Figure 8). Nevertheless, several adenine residues seem to be conserved on one side of the Fur operator. The contribution of these adenines to the HpFur-DNA interaction remains to be investigated. On the other hand, our analysis of the fecA1, fecA2 and frpB1 promoters revealed the presence of a conserved region (CR1) located between 18 and 23 nucleotides upstream from the predicted -10 elements (Figure 1A). Mutation of this region in all three promoters completely abolished CAT expression in H. pylori (data not shown) indicating a critical role for this region in transcriptional initiation. Though H. pylori promoters appear to be devoid of conserved -35 boxes (Sharma et al., 2010), the resemblance of the sequences containing CR1 to the canonical -35 elements extensively characterized in E. coli is apparent (Shultzaberger et al., 2007).

Figure 8.

Sequence logo (Crooks et al., 2004) generated for all the functional endogenous Fur boxes identified in this work. The logo consists of stacks of letters, one stack for each position in the sequence analyzed. The overall height of each stack indicates the sequence conservation at that position (measured in bits). The nucleotides corresponding to the Fur box are shown in bold and the seven defined positions are underlined.

Previous studies demonstrated that synthetic promoters carrying de novo introduced Fur boxes mediate Fur-regulated expression of otherwise non-Fur-regulated genes (Calderwood and Mekalanos, 1988; Wooldridge et al., 1994). In the present work, we used a similar strategy to analyze the effect in vivo of a different location of the Fur box within a synthetic promoter in H. pylori (Figure 4). Fur repression was only achieved with Fur boxes introduced nearby the promoter elements. Moreover, maximum repression was observed with Fur boxes overlapping the -10 or -35 elements. In contrast, the promoter did not become Fur-regulated when the Fur box was introduced either immediately after or more than 43 nucleotides upstream from the transcriptional start point. This result was unexpected since Fur boxes located in these positions are proficient in mediating Fur regulation of numerous genes. This is the case for the Fur boxes present in the promoters of pdxJ, located (centered) immediately after the transcriptional start point in H. pylori, and the Fur boxes present in the promoters of hpn2 and amiE genes, located more than 50 nucleotides upstream from the transcriptional start sites (Figure 3). Therefore, the behavior of the synthetic promoter used in this study seems to be different from that of the endogenous Fur-regulated promoters. One possible explanation for this discrepancy might be the absence in our synthetic promoter of distal elements that stimulate transcription. Briefly, it is possible that the hpn2 and amiE genes contain a third promoter element that increases the affinity of RNAP for the DNA, which is located upstream from the -35 region and close to the Fur box. Fur binding to operators located near these upstream elements would impede the positive effect on transcription exerted by these sequences. These types of upstream elements have been shown to increase transcription of a number of bacterial promoters (Estrem et al., 1998; Ross et al., 1993; Ross et al., 1998) and in fact, it has been reported that operator I of the fur promoter of H. pylori functions both as a Fur binding site and an upstream element that enhances transcription of the fur locus (Delany et al., 2003). Based on this premise, we hypothesize that location and sequence of every single Fur box is in great harmony with the intrinsic features of the regulated promoter (architecture, strength, presence of enhancers, etc).

It has been shown that genes exhibiting distal Fur boxes within the promoter (more than 70 nucleotides upstream from the transcriptional start site) are up-regulated by Fur and iron. This is the case for pan1, norB and the nuoABCDE genes from Neisseria gonorrhoeae, encoding metalloproteins/complexes involved in anaerobic and aerobic respiration, respectively (Delany et al., 2004). In our study, we found that the de novo introduction of a Fur box in the distal region of the babB promoter did not influence CAT expression (Figure 4), suggesting that the presence of a Fur box is not sufficient to activate gene expression. Since typically Fur acts as a repressor, we cannot rule out the possibility that Fur activation is actually achieved by Fur blocking accessibility of the DNA to another repressor; hence, promoters devoid of the target for the second repressor cannot be subject to Fur activation. In this hypothetical situation, of course, Fur interaction with the DNA should not interfere with RNAP binding to the promoter.

Positive regulation by iron-bound Fur in H. pylori has been demonstrated for two genes, which encode the Fe-S cluster synthesis protein NifS (HPG27_201) (Alamuri et al., 2006) and the oxoglutarate oxidoreductase ferredoxin subunits OorDABC (HPG27_548-551) (Gancz et al., 2006). Likewise, our results suggest that the expression of the virulence gene cagA is also activated by metal-bound Fur in H. pylori (Figure 6). Fur-dependent activation of cagA is supported by recent RNase protection assay data reported by our laboratory (Gancz and Merrell, 2011). Similarly, previous deletion analyses of the cagA promoter determined that the DNA region located between positions -29 and -80 was necessary for full expression of this gene (Spohn et al., 1997). This activator effect was tentatively attributed to the presence of an upstream element facilitating RNAP binding to the cagA promoter, which is devoid of a canonical -35 element. However, our finding that cagA is upregulated by Fur provides an alternative explanation to the observed phenotype. It is also notable that cagA activation by metal-bound Fur is in agreement with the anticipated role of iron on cagA expression (Ernst et al., 2005). A recent report revealed also a defect of ΔcagA mutants to colonize iron-deficient gerbils, establishing a link between cagA, iron uptake and Fur (Tan et al., 2011).

In addition, we provide experimental evidence for Fur-dependent inactivation of at least six novel genes belonging to different functional categories: HPG27_51, HPG27_52, HPG27_199, HPG27_445, HPG27_825 and HPG27_1063 (Figure 6). The benefit of having these genes under control of Fur and iron is presently unclear. However, as we predicted earlier, some of these genes have been shown to play a role in pathogenesis in Helicobacter. For instance, disruption of the putA gene in H. hepaticus (homologous to HPG27_51) leads to reduced inflammation in infected mice (Krishnan et al., 2008). Similarly, two different studies have demonstrated a role for H. pylori Gamma-glutamyltransferase (HPG27_1063) in gut colonization (Chevalier et al., 1999; McGovern et al., 2001). Moreover, a recent report has implicated this enzyme in the observed apoptotic death of human gastric epithelial cells induced by Helicobacter (Flahou et al., 2011). Fur regulation of Gamma-glutamyltransferase might be related to the proposed role of this enzyme in the reduction of extracellular iron (Zarnowski et al., 2008), which may provide a more effective iron source for the bacteria. In this sense, reduction of insoluble Fe3+ to soluble Fe2+, followed by transport of Fe2+ to the cytoplasm, constitutes an important step in iron acquisition. Interestingly, flavins have also been implicated as electron donors in this poorly understood process (von Canstein et al., 2008). This fact may explain why the expression of enzymes that use FAD as a cofactor, as is the case of putA, are under the control of Fur.

Based on the transcriptome analysis of Sharma et al., transcription of HPG27_51 (HP0056), HPG27_199 (HP0218), HPG27_445 (HP0486) and HPG27_1063 (HP1118) initiates at extended -10 elements with sequences 5’-TGCTACAAT-3 ’ o r 5 ’-TGTTATAAT-3’. The Fur box present in the HPG27_1063 promoter overlaps the predicted -10 element. For HPG27_51, HPG27_199 and HPG27_445, the distance from the identified Fur boxes to the corresponding transcriptional start sites is approximately 50, 60, 240 nucleotides, respectively (Sharma et al., 2010). It is unclear how a Fur box located 240 nucleotides upstream from the transcriptional start site could inactivate HPG27_445 transcription. The promoter elements of HPG27_52 (HP0057) and HPG27_825 (HP0871) are not apparent and the relative location of their respective Fur boxes could not be determined. With the exception of the Fur box present in the promoter of HPG27_199, the Fur boxes of the novel genes that are subject to Fur-inactivation are not fully conserved among H. pylori strains, suggesting that Fur regulation might be strain specific (Supplementary Table 1).

Differences in Fur regulation between H. pylori strains are not rare and in this sense, expression of the sodB gene (HPG27_1008), which encodes an iron-dependent superoxide dismutase, is Fur-regulated in strain 26695 but not in other H. pylori strains (Carpenter et al., 2009). Likewise, while previous analysis performed in strain 26695 suggested otherwise (van Vliet et al., 2002), our results indicate that expression of frpB2/3, which is involved in iron transport and storage, is not regulated by Fur in strain G27 (Figure 6). The absence of apparent Fur box-like sequences in the promoters of genes that appear to be Fur-regulated, like feoB or frpB2/3 in strain 26695, is puzzling and indicates that Fur regulation might be either indirect or mediated by DNA targets significantly different from the Fur box consensus identified herein. To this end, the feoB promoters in strains G27 and 26695 display a putative Fur box sequence (TAACAATTAGTCTTA) that shows 3 mismatches (underlined) with respect to the consensus. Whether Fur boxes carrying more than two nucleotide substitutions are functional remains to be investigated. However, this is very likely since some positions of the Fur operator are expected to be more important than others. In fact, our sequence logo suggests that the residues located at the ends of each heptameric repeat are more conserved and so, they are probably more important than the central residues (Figure 8). Interestingly, two out of the three mismatches present in the putative Fur box of the feoB promoter correspond to less conserved positions. Hence, the integration of additional criteria to scan the H. pylori genome for Fur box-like sequences will facilitate the future identification of new Fur binding sites.

On the other hand, our results regarding Fur regulation of the exbB2 and nikR genes are contradictory. Interestingly, previous analyses addressing Fur regulation of these two genes also raised contradictory conclusions. For instance, exbB2 was shown to be repressed by iron-bound Fur in two independent transcriptional analyses (Ernst et al., 2005; Gancz et al., 2006). However, Ernst and coworkers found that the exbB2-exbD2-tonB2 operon was constitutively transcribed in both the WT strain (26695) and a fur mutant derivative (Ernst et al., 2006). Similarly, despite footprinting analyses support Fur binding to the nikR promoter, expression of this gene was not found to be Fur-dependent in previous transcriptional analysis (Ernst et al., 2005; Gancz et al., 2006). These types of contradictions are not isolated and accordingly, the prior finding that Fur binds to the ceuE1 promoter (Delany et al., 2001) is not supported by transcriptional analysis of this gene (van Vliet et al., 2002). The fact that Fur binds to the promoters of exbB2, nikR and ceuE1 with very low affinity reinforces that the mechanism of Fur regulation of these genes is convoluted.

Finally, our bioinfomatic analysis of the G27 genome reveals the presence of putative Fur boxes inside coding regions (Table 2). Fur binding to DNA segments located inside ORFs was previously observed in H. pylori through Fur chromatin immunoprecipitation (Danielli et al., 2006). However, the functionality of these internal operators has not been verified. Two of the internal Fur boxes identified in our work deserve further attention. First, the presence of a Fur box at the 3’ end of the HPG27_357 gene (Table 2) is supported by previous data (Beier et al., 1997); a plasmid containing this chromosomal region from strain 26695 was positive by FURTA-Hp. In particular, this clone contained a 480-bp insert encompassing the 3’ end of HP1071 and the 5’ end of HP1072. HP1071 is the homolog of HPG27_357 in strain 26695 and both genes carry a Fur box sequence near the 3’ end. Since HP1072 (located immediately downstream) encodes a copper-transporting ATPase (CopA), the positive FURTA-Hp phenotype was attributed to the expression of a CopA truncated fragment containing a metal-binding domain. However, our results suggest that the observed derepression of the reporter gene by FURTA might be due to the presence of multiple copies of the Fur binding site. On the other hand, the internal Fur box identified at the 3’ end of HPG27_547 is located adjacent to a gene that has been shown to be activated by iron-bound Fur (Gancz et al., 2006). Accordingly, as mentioned earlier, HPG27_548 encodes a subunit of the oxoglutarate oxidoreductase ferredoxin (OorD) that is activated by iron-bound Fur (Gancz et al., 2006). The possible role of this Fur box in the upregulation of oorD will be addressed in a separate study (manuscript in preparation).

Along with the recent elucidation of the tridimensional structure of HpFur (Dian et al.), the identification of the DNA target for iron-bound Fur described herein, provides the essential tools to carry out biochemical analyses aimed to comprehend the mechanics of DNA binding of this unique repressor protein. Likewise, the discovery of at least seven novel loci regulated by iron-bound Fur, including the gene encoding for the major H. pylori cytoxin, CagA, is pivotal in order to understand the role of Fur in pathogenesis and stress adaptation in H. pylori. In summary, this study provides the fundamentals to further understand Fur regulation in H. pylori.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains, media and culture conditions

E. coli strains were grown on LB medium supplemented with 100 μg ml-1 ampicillin (Sigma) or 25 μg ml-1 kanamycin (Gibco) when required. All DNA cloning was performed in DH5-α electrocompetent cells (Hanahan 1983). H. pylori strains were grown on horse blood agar (HBA) plates containing 4% Columbia agar base (EMD Chemicals, Inc.), 5% defibrinated horse blood (HemoStat Laboratories, Dixon, CA), 0.2% β-cyclodextrin (Sigma), 10 μg ml-1 vancomycin (Amresco), 5 μg ml-1 cefsulodin (Sigma), 2.5 U ml-1 polymyxin B (Sigma), 5 μg ml-1 trimethoprim (Sigma), and 8 μg ml-1 amphotericin B (Amresco). H. pylori liquid cultures were grown with shaking at 100 rpm in brucella broth supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 10 μg ml-1 vancomycin at 37°C. Where noted, plates and cultures were supplemented with 25 μg ml-1 kanamycin or 5% sucrose (Sigma). Both plate and liquid cultures were grown in gas evacuation jars under microaerophilic conditions (5% O2, 10% CO2, 85% N2) generated with an Anoxomat gas evacuation and replacement system (Spiral Biotech). H. pylori strains were maintained as frozen stocks in brain heart infusion medium supplemented with 20% glycerol and 10% FBS (Gibco) at -80°C. All H. pylori strains obtained in this work are derivatives of G27 (Baltrus et al., 2009), including the three different isogenic fur deletion mutants employed: DSM300 (Carpenter et al., 2007), DSM391 (Carpenter et al., 2010) and DSM925 (this study).

Recombinant DNA Techniques

General DNA manipulations were performed according to Sambrook & Russell (2001) (Sambrook and Russell, 2001). Restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs. Plasmid DNA was prepared using Qiaprep spin columns from Qiagen. PCR was carried out using Phusion High Fidelity DNA Polymerase from New England Biolabs or GoTaq Hot Start Polymerase from Promega. DNA gel extraction and PCR purification were performed using the corresponding Quiaquick kits from Qiagen. All primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Construction of a markless Δfur mutant (DSM925) by allelic exchange

A plasmid carrying the sequences upstream and downstream of the fur coding sequence was obtained by SOE (splicing by overlap extension) in a series of 3 PCR reactions. In the first PCR, the FurCF1-XbaI and HpUKanSacR primers were used to amplify the sequence upstream of fur in G27 (340 bp). In the next round, HpDKanSacF and HpDKanSacR were used to amplify the sequence downstream of fur (339 bp). These products were purified, mixed and the SOE reaction performed using the FurCF1-XbaI and HpDkanSacR primers. This PCR product (679 bp) was then subcloned into pGEMT-Easy (Promega) and the proper insert verified by EcoRI dropout, XhoI and SmaI single digestion and sequencing. The resulting plasmid, designated p386, was transformed into H. pylori strain DSM391, which was initially created to move unmarked fur mutations into the chromosome in the native location of fur (Carpenter et al., 2010). In this strain, the fur coding sequence has been replaced by a kan-sacB cassette that confers kanamycin resistance and sucrose sensitivity. Double crossover between p386 and the DSM391 genome deletes the kan-sacB cassette and generates a clean fur deletion mutant. Transformants displaying a sucrose resistant and kanamycin sensitive phenotype were propagated and the intended deletion of the kan-sacB cassette was confirmed by PCR using primers furDown-R and furUp-F. Sequencing reactions of the PCR product (825 bp) using the same primers confirmed the fur deletion.

Construction of the promoter::cat fusions

All of the promoter::cat fusions generated in this work are listed in Table 3. The chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat) coding region was originally amplified by PCR from plasmid pBAD33 (Beckwith Lab) using primers catEC-5’ and catEC-3’. The PCR product (~600 bp) was digested with BamHI and PstI and cloned into the similarly digested pTM117 plasmid (Carpenter et al., 2007). The resulting plasmid carries a promoterless (Pless) cat gene fused to the Shine Dalgarno (S/D) sequence of flaA, which has been previously used for the expression of heterologous genes in H. pylori (Copass et al., 1997). Most of the transcriptional fusions were created in a single-step PCR reaction using a specific forward primer carrying the target promoter region (see Supplementary Table 2), the S/D sequence and the 5’ end of cat, catEC-3’ as a reverse primer and Pless::cat as a template. For the construction of PribBA::cat, Phpn2::cat, PamiE::cat, PbabB-60::cat and PbabB-100::cat, we also used a specific forward primer and catEC-3’ as a reverse primer, but the transcriptional fusions PribBA(-)::cat, Phpn2(-)::cat, PamiE(-)::cat, PbabB-43::cat and PbabB-60::cat, respectively, were used as template for the PCR reaction. PexbB2::cat was obtained by two sequential PCR reactions. In the first reaction, we utilized primers exbB2-1 and catEC-3’, and Pless::cat as a template. The resulting PCR product was used as a template in a second PCR reaction using primers exbB2-2 and catEC-3’. PbabB-140::cat was obtained by SOE in two PCR reactions. In the first reaction, the desired region of the babB promoter was amplified from strain 26695 using primers babB-140 and babB-140-3’. Strain 26695 was used as a template for the PCR amplification because the babB coding region is not present in the genome of G27. The resulting PCR product was mixed with Pless::cat and used as a template in a second PCR reaction using primers babB-140 and catEC-3’. All the PCR products carrying the aimed transcriptional fusions were digested with BamHI and PstI and cloned into the similarly digested pTM117 plasmid. Finally, each fusion was verified by sequencing using primer apha3-2, which anneals adjacent to the BamHI site in plasmid pTM117.

Table 3.

Transcriptional fusions generated in this work

| Name | Description | Strain numbers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| G27 | Δ fur* | ||

| Pless::cat | Promoterless cat coding region | DSM989 | DSM990 |

| PfecA1::cat | Promoter region of fecA1 gene (coordinates 703659-703700) fused to cat coding region | DSM991 | DSM992 |

| PfecA2::cat | Promoter region of fecA2 gene (coordinates 832457-832498) fused to cat coding region | DSM993 | DSM994 |

| PfrpB1::cat | Promoter region of frpB1 gene (coordinates 895811-895853) fused to cat coding region | DSM995 | DSM996 |

| PnikR::cat | Promoter region of nikR gene (coordinates 1390795-1390837) fused to cat coding region | DSM997 | DSM998 |

| PexbB2::cat | Promoter region of exbb2 gene (coordinates 1390849-1390922) fused to cat coding region | DSM999 | DSM1000 |

| PpdxJ::cat | Promoter region of pdxJ gene (coordinates 1645009-1645048) fused to cat coding region | DSM1001 | DSM1002 |

| PpdxJ(mut)::cat | PpdxJ::cat with mutated Fur box sequence | DSM1003 | DSM1004 |

| PamiE::cat | Promoter region of amiE gene (coordinates 306594-306665) fused to cat codding region | DSM1005 | DSM1006 |

| PamiE(-)::cat | Promoter region of amiE gene (coordinates 306610-306665) fused to cat coding region | DSM1007 | DSM1008 |

| Phpn2::cat | Promoter region of hpn2 gene (coordinates 1465943-1466009) fused to cat coding region | DSM1009 | DSM1010 |

| Phpn2(-)::cat | Promoter region of hpn2 gene (coordinates 1465958-1466009) fused to cat coding region | DSM1011 | DSM1012 |

| PribBA::cat | Promoter region of ribBA gene (coordinates 828328-828380) fused to cat coding region | DSM1013 | DSM1014 |

| PribBA(-)::cat | Promoter region of ribBA gene (coordinates 828328-828371) fused to cat coding region | DSM1015 | DSM1016 |

| PbabB::cat | Promoter region of babB gene (coordinates 949749- 949790) fused to cat coding region | DSM1017 | DSM1018 |

| PbabB+10::cat | PbabB::cat with de novo Fur box sequence introduced at position +10 | DSM1019 | DSM1020 |

| PbabB-4::cat | PbabB::cat with de novo Fur box sequence introduced at position -4 | DSM1021 | DSM1022 |

| PbabB-19::cat | PbabB::cat with de novo Fur box sequence introduced at position -19 | DSM1023 | DSM1024 |

| PbabB-23::cat | PbabB::cat with de novo Fur box sequence introduced at position -23 | DSM1025 | DSM1026 |

| PbabB-43::cat | PbabB::cat with de novo Fur box sequence introduced at position -43 | DSM1027 | DSM1028 |

| PbabB-60::cat | PbabB::cat with de novo Fur box sequence introduced at position -60 | DSM1029 | DSM1030 |

| PbabB-100::cat | PbabB::cat with de novo Fur box sequence introduced at position -100 | DSM1031 | DSM1032 |

| PbabB-140::cat | PbabB::cat with de novo Fur box sequence introduced at position -140 | DSM1033 | DSM1034 |

| PbabBFur-23::cat | PbabB::cat with de novo reference Fur box sequence introduced at position -23 (Baichoo and Helmann, 2002) | DSM1039 | DSM1040 |

| PbabBPerR-23::cat | PbabB::cat with de novo PerR box sequence introduced at position -23 (Baichoo and Helmann, 2002) | DSM1041 | DSM1042 |

G27 or Δfur indicates the background in which each particular strain was created

Analysis of CAT expression

CAT expression was determined using a CAT ELISA kit (Roche Diagnostics). Briefly, 1.5 ml of overnight H. pylori cultures (OD 0.5-0.8) were centrifuged at 13200 r.p.m, washed with PBS and lysed using the ELISA kit lysis buffer. Identity of the fusions was confirmed by sequencing the promoter region preceding cat using the same procedure described above; the actual lysate was used as a template. Protein concentrations of lysates were determined using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) reagent kit (Pierce). 100 ng of lysate protein was typically added to each ELISA plate well, though some transcriptional fusions were also analyzed using 25 ng of lysate. Absorbance data were obtained using a Spectramax M2 ELISA plate reader (Molecular Devices). Experiments were conducted multiple times with similar results. When required, iron deprivation was achieved by growth in the presence of 60 μM DPP, as previously reported (Carpenter et al., 2007). This concentration of DPP does not deplete all the available iron and does not significantly hinder H. pylori growth.

RNA manipulation

Briefly, liquid cultures were inoculated for each strain and grown in BB supplemented with 10% FBS (iron abundant) to exponential phase. One half of each culture was then removed for RNA isolation, and 200 μM of DPP was added to the remaining half of each culture to create an iron depletion shock environment (Merrell et al., 2003). The cultures were maintained for an additional hour prior to RNA isolation as previously described (Thompson et al., 2003). RNA concentration was then quantified using a ND-1000 nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) and the integrity of the RNA was confirmed by visualization on agarose gels.

RNA Dot blot

Total RNA (2.5 μg) was directly spotted onto nylon membranes (Roche) using a manifold vacuum apparatus and was covalently bound to the membrane by cross-linking (~120 J/cm) using a Stratalinker 18000 UV crosslinker (Stratagene). DNA probes were generated by PCR-amplification of an internal fragment of each target gene using the primers listed in Supplementary Table 2 and G27 genomic DNA as a template. The resulting PCR fragments, which were all of a size between 200 and 400 bp, were labeled with digoxigenin using DIG-High Prime Mix from Roche. Hybridizations with ULTRAhyb Buffer (Ambion) and stringency washes were performed at 42°C and 58°C, respectively, using a HB-1000 Hybridizer (UVP). Bound probe was visualized using the chemiluminescent substrate CSDP provided in the DIG-High Prime DNA Labeling and Detection Starter Kit II (Roche). Afterwards, blots were exposed to a LAS-3000 Image Reader (FujiFilm) and data analyzed using Multi-Gauge software (version 3.0; FujiFilm). At least two independent biological repeats of each experiment were conducted.

Primer extension

The promoter regions of pdxJ and ribBA were amplified by PCR using two different sets of primers: pdxJ-5’/pdxJ-3’and ribBA-5’/ribBA-3’, respectively. The resulting PCR products were cloned into the pBE plasmid, a derivative of the pBluescript plasmid (Stratagene) in which all the restriction sites but EcoRV have been eliminated. Plasmids pBEpdxJ and pBEribBA were then used as a template to perform standard sequencing reactions using primers pdxJ-3’ and ribBA-3’. In parallel, first-strand synthesis was carried out using Primer Extension System-AMV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega) by annealing 1 pmol of 5'-6FAM-labelled primers with 2 μg of total RNA. Labeled primers were the same as employed for the sequencing reactions. Different amounts of the primer extension reaction were mixed with their corresponding sequencing reactions and analyzed using an ABI 3500×L Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Fur binding to the promoters of the newly identified Fur-regulated genes was analyzed by EMSA. DNA fragments of the intergenic regions encompassing the candidate Fur boxes, were PCR amplified using G27 genomic DNA and the primers described in Supplementary Table 2. The intergenic DNA fragments subject to EMSA analysis were 120 to 150 bp long, with the only exception of the intergenic region between HPG27_825 and HPG27_826 that was 290 bp long. A 132 bp fragment of the frpB1 promoter and a 244 bp fragment of the rpoD promoter were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The PCR products were purified using Performa DTR gel filtration cartridges (Edge Bio). Then, 150 ng of each promoter fragment was end labeled with 32P and cleaned as previously described (Carpenter et al., 2009; Gancz et al., 2006). Some differences in the labeling efficiency of the DNA fragments analyzed were observed. Finally, fifty microliters of MnCl2 binding buffer (MnCl2-BB) was added to the eluted promoter fragments.

Purification of HpFur was performed as previously described (Carpenter et al., 2009). HpFur binding to each intergenic region of interest was assessed in the presence of the rpoD promoter as an internal negative control; equal amounts of the two end labeled templates were used. EMSAs were performed under iron substitution conditions achieved through the use of MnCl2 as previously described (Carpenter et al., 2010). Fur concentrations used were 0, 14.8, 37, 74 and 148 ng ml-1. In the competition reaction mixtures (CC), 250 ng of unlabeled DNA corresponding to the intergenic region of interest, was added to the reaction containing 148 ng ml-1 of HpFur. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min at 37°C and separated on a 5% polyacrylamide gel composed of 5% 19:1 acrylamide, 1x Tris-glycine (TG) buffer, 2.5% glycerol, and 0.133 mM MnCl2, and the gels were run in 1x TG buffer. Samples were electrophoresed at 70 V for 2.5 or 3 h, gels were exposed to phosphor screens, and screens were scanned using an FLA-5100 multifunctional scanner (Fuji-Film).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS