Abstract

Summary

Background and objectives

Congestive heart failure (CHF) is a major risk factor for death in end-stage kidney disease; however, data on prevalence and survival trends are limited. The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence and mortality effect of CHF in successive incident dialysis cohorts.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

This was a population-based cohort of incident US dialysis patients (n = 926,298) from 1995 to 2005. Age- and gender-specific prevalence of CHF was determined by incident year, whereas temporal trends in mortality were compared using multivariable Cox regression.

Results

The prevalence of CHF was significantly higher in women than men and in older than younger patients, but it did not change over time in men (range 28% to 33%) or women (range 33% to 36%). From 1995 to 2005, incident death rates decreased for younger men (≤70 years) and increased for older men (>70 years). For women, the pattern was similar but less impressive. During this period, the adjusted mortality risks (relative risk [RR]) from CHF decreased in men (from RR = 1.06 95% Confidence intervals (CI) 1.02–1.11 in 1995 to 0.91 95% CI 0.87–0.96 in 2005) and women (from RR = 1.06 95% CI 1.01–1.10 in 1995 to 0.90 95% CI 0.85–0.95 in 2005 compared with referent year 2000; RR = 1.00). The reduction in mortality over time was greater for younger than older patients (20% to 30% versus 5% to 10% decrease per decade).

Conclusions

Although CHF remains a common condition at dialysis initiation, mortality risks in US patients have declined from 1995 to 2005.

Introduction

Congestive heart failure (CHF) is a common cardiovascular condition at dialysis initiation and contributes substantially to increased mortality risk (1–5). The high prevalence in part is attributed to an increasing burden of known cardiovascular risk factors as well as uremia-specific factors accumulating in the predialysis period (1,2). Several studies to date have improved our understanding of the natural history of CHF in dialysis cohorts (1,2). Much interest has focused on the potential roles of anemia management, blockade of the renin-angiotensin and adrenergic systems, and selective use of dialysis modalities as potential intervention strategies for improving patient survival (6–10). However, few of these studies to our knowledge have addressed the outcomes for contemporary dialysis cohorts with CHF. Furthermore, little is known about temporal trends in CHF prevalence and its associated mortality.

Whether survival from CHF has improved over time among patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) has not, to our knowledge, been previously explored in large-scale studies. Theoretically, there are several reasons to believe that survival may have improved over time. Earlier initiation of dialysis, improved cardiovascular care, improvements in pre- and postdialysis care, the introduction of evidence-based guidelines, and the adoption of validated core indicators in dialysis delivery are principal considerations (11–18). On the other hand, it is possible that survival from CHF may have worsened over time because of greater acceptance of older and sicker patients, including more severe cases of CHF (11).

The purpose of the study presented here was to determine patterns in prevalence and associated mortality risks for incident dialysis patients with CHF in successive annual cohorts and to evaluate the effect of time trends on patient survival.

Study Population and Methods

Data

These hypotheses were tested in a historical prospective cohort of 926,298 incident US patients who began dialysis between May 1, 1995, and December 31, 2005. Data sufficient for these analyses were obtained from the Standard Analysis Files of the US Renal Data System (USRDS). The Medical Evidence Standard Analysis File is derived from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Medical Evidence Form, a government document that is completed for all new patients initiated on dialysis (19). The CMS form captures data on demographic characteristics, comorbid conditions, lifestyle characteristics, measures of functional status, laboratory indices, and date and type of dialysis treatment provided for all incident patients. The form is completed by medical personnel who care for patients in each dialysis facility through data abstraction from patients' medical records. The presence or absence of CHF as recorded on the CMS Medical Evidence Form served as the indicator for CHF presence, and the validity of this measure has been evaluated in prior studies (19,20).

Ascertainment of Mortality

Mortality data were captured through the CMS Death Notification Form (11). This document recorded the date and cause of death for all patients who received renal replacement therapy in the United States. The Medical Evidence data set (n = 1,059,699) was merged with the USRDS mortality data set by unique identification number. Patients were systematically excluded if the Medicare identification number prevented linkage with the mortality data set or if the number of days at risk could not be calculated (n = 46,649), if dates of initiation fell outside of the May 1995 to December 2005 timeframe (n = 77,684), or if patients were <18 years of age (n = 9068). After exclusion, there were 926,298 patients available for the proposed analyses.

Statistical Analyses

The prevalence of CHF was determined for the entire cohort by calendar year. The Chi-square and ANOVA models were used to test for differences among groups and across calendar periods. Gender-specific prevalence estimates were compared stratified by age (18 to 50, 50 to 70, and >70 years). Multivariate logistic regression analysis determined the independent relationships of demographic, clinical, laboratory, lifestyle factors, and predialysis erythropoietin use with CHF. These associations were represented by adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Incidence death rates were calculated as the number of death events divided by person-time of follow-up among those with CHF at baseline for each calendar year, 1995 to 2005. Cox regression modeled survival times for successive incident cohorts with the year 2000 used as referent. The study start date was the date of the first regular dialysis and patients were followed until the earliest of death, loss to follow-up, kidney transplantation, or to the end of follow-up (October 2006). Multivariate models of increasing complexity evaluated the association of calendar year on all-cause mortality. Adjusted Cox survival rates were calculated and compared. Covariates for adjustment included age at study start, gender, race, diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular and cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive lung disease, malignancy or neoplasm, body mass index, current tobacco use, alcohol dependence, inability to walk, serum albumin, hematocrit, estimated level of kidney function from the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation, and erythropoietin use before dialysis onset (21). For each exposure, the relative risk of death (RR) and 95% CI were determined in univariate and multivariate analyses. All analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software (version 9.12, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Cohort

The study cohort included 926,298 individuals who commenced dialysis therapy between May 1995 and December 2005. The mean age of study subjects was 62.8 years old, 54% were men, and most were white. Table 1 compares baseline characteristics of consecutive incident cohorts across calendar years 1995 to 2005. In general, successive incident cohorts were characterized by older age, higher proportion of men and cardiovascular conditions, higher levels of kidney function (estimated GFR) and hematocrit values at dialysis initiation, lower serum albumin levels, and increasing use of hemodialysis as the primary dialysis modality. Table 2 describes the correlates of CHF at dialysis onset. Several known cardiovascular conditions were independently and significantly associated with CHF, including coronary disease (AOR = 2.97), peripheral vascular disease (AOR = 1.74), and stroke (AOR = 1.09). Similarly, hypertension (AOR = 1.32), diabetes (AOR = 1.70), poor functional status (inability to walk; AOR = 1.65), and alcohol dependence (AOR = 1.15) were associated with CHF, whereas predialysis use of erythropoietin was associated with less likelihood of CHF (AOR = 0.95).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients in the US dialysis population by year of incidence: 1995 to 2005

| Demographics | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean years (SD)c | 60.8 (15.7) | 61.3 (15.7) | 62.1 (15.5) | 62.4 (15.5) | 62.6 (15.5) | 62.9 (15.5) | 63.1 (15.4) | 63.3 (15.4) | 63.4 (15.3) | 63.4 (15.3) | 63.4 (15.4) |

| Gender | |||||||||||

| male, %c | 52.1 | 53.1 | 53.2 | 53.0 | 53.3 | 53.4 | 53.7 | 54.3 | 54.0 | 55.1 | 55.6 |

| female, %c | 47.9 | 46.9 | 46.9 | 47.0 | 46.7 | 46.6 | 46.3 | 45.7 | 46.1 | 44.9 | 44.4 |

| Race | |||||||||||

| white, %c | 63.4 | 63.5 | 64.8 | 64.7 | 65.3 | 66.3 | 66.4 | 65.9 | 65.9 | 66.5 | 66.2 |

| black, %c | 32.2 | 32.1 | 31.0 | 31.0 | 30.0 | 29.0 | 28.8 | 29.3 | 29.3 | 28.6 | 28.8 |

| Asian, %c | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 3.9 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native, %c | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Comorbid conditions | |||||||||||

| diabetes, %c | 48.1 | 49.7 | 50.0 | 50.8 | 51.6 | 52.8 | 53.7 | 53.6 | 54.1 | 54.7 | 55.4 |

| coronary disease, %c | 23.7 | 25.3 | 26.8 | 26.9 | 26.7 | 27.5 | 27.8 | 27.5 | 27.5 | 27.6 | 24.6 |

| cerebrovascular disease, %c | 8.1 | 8.8 | 9.4 | 9.3 | 9.2 | 9.3 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 9.4 | 9.2 | 9.6 |

| peripheral vascular disease, %c | 13.8 | 14.4 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 14.6 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 14.1 | 14.3 | 14.0 | 14.7 |

| hypertension, %c | 67.7 | 71.6 | 73.9 | 74.4 | 75.5 | 77.0 | 78.6 | 79.6 | 80.6 | 81.3 | 82.6 |

| COPD, %c | 6.7 | 6.9 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 7.4 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 8.0 | 8.2 | 8.8 |

| malignancy, %c | 4.8 | 4.8 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.4 | 5.7 | 6.0 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 6.4 | 7.2 |

| alcohol dependence, %c | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 |

| current tobacco use, %c | 6.1 | 6.0 | 5.7 | 5.3 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 5.9 |

| inability to walk, %c | 5.0 | 4.7 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 5.9 |

| Laboratory variables | |||||||||||

| serum creatinine, mg/dl (SD)c | 8.1 (3.4) | 8.3 (3.5) | 8.5 (3.5) | 8.8 (3.7) | 9.1 (3.7) | 9.2 (3.8) | 9.3 (3.8) | 9.3 (3.8) | 9.4 (3.9) | 9.5 (3.8) | 9.5 (3.8) |

| estimated GFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 (SD)a,c | 7.0 (2.8) | 7.1 (2.8) | 7.3 (2.9) | 7.6 (3.1) | 7.8 (3.2) | 8.0 (3.3) | 8.2 (3.3) | 8.4 (3.4) | 8.6 (3.4) | 8.7 (3.5) | 8.8 (3.5) |

| albumin, mg/L (SD) | 3.3 (0.7) | 3.3 (0.7) | 3.2 (0.7) | 3.2 (0.7) | 3.1 (0.7) | 3.1 (0.7) | 3.1 (0.67) | 3.1 (0.7) | 3.1 (0.7) | 3.1 (0.7) | 3.1 (0.7) |

| hematocrit, mean (SD)c | 27.9 (5.5) | 27.9 (5.5) | 28.4 (5.4) | 28.7 (5.4) | 29.1 (5.4) | 29.5 (5.5) | 29.8 (5.5) | 30.0 (5.5) | 30.3 (5.4) | 30.5 (5.2) | 30.6 (5.3) |

| Predialysis erythropoietin use | |||||||||||

| erythropoietin, %c | 21.8 | 23.5 | 24.2 | 26.1 | 27.7 | 29.1 | 31.1 | 32.5 | 32.5 | 32.8 | 32.0 |

| Dialysis modalityb | |||||||||||

| hemodialysis, %c | 85.1 | 87.4 | 89.1 | 90.6 | 91.3 | 91.8 | 92.0 | 92.7 | 92.7 | 93.1 | 93.3 |

| peritoneal dialysis, %c | 14.9 | 12.6 | 10.9 | 9.4 | 8.7 | 8.2 | 8.0 | 7.3 | 7.3 | 6.9 | 6.7 |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Estimated GFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) was based on the abbreviated Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study equation before dialysis onset.

Dialysis modality assignment, peritoneal dialysis, and hemodialysis defined on day 90 of end-stage kidney disease.

P < 0.001 for comparison of baseline characteristics across calendar years.

Table 2.

Factors associated with the presence of heart failure at dialysis onset among US dialysis patients

| Variable | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Demographic | |

| age (years) | |

| 18 to 40 (referent) | 1.00 |

| 40 to 50 | 1.16 (1.13 to 1.19) |

| 50 to 60 | 1.54 (1.51 to 1.58) |

| 60 to 70 | 1.91 (1.87 to 1.95) |

| 70 to 80 | 2.37 (2.32 to 2.42) |

| >80 | 3.13 (3.05 to 3.20) |

| gender | |

| male (versus female) | 0.83 (0.82 to 0.84) |

| race | |

| white (referent) | 1.00 |

| black | 0.99 (0.98 to 1.00) |

| Asian | 0.84 (0.81 to 0.86) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.10) |

| Comorbid conditions | |

| diabetes (versus no) | 1.70 (1.68 to 1.71) |

| pulmonary disease (versus no) | 2.16 (2.12 to 2.19) |

| coronary disease (versus no) | 2.97 (2.94 to 3.01) |

| peripheral vascular disease (versus no) | 1.74 (1.72 to 1.77) |

| stroke (versus no) | 1.09 (1.07 to 1.11) |

| hypertension (versus no) | 1.32 (1.30 to 1.37) |

| cancer (versus no) | 0.81 (0.80 to 0.83) |

| Lifestyle factors | |

| current tobacco use (versus no) | 0.97 (0.95 to 0.99) |

| alcohol dependence (versus no) | 1.15 (1.10 to 1.20) |

| Functional status | |

| inability to walk (versus no) | 1.65 (1.61 to 1.69) |

| erythropoietin before dialysis (versus no) | 0.95 (0.94 to 0.96) |

Multivariable analysis of factors associated with heart failure at dialysis initiation. Model included demographic, clinical, and biochemical variables measured at dialysis onset. n = 926,298 for adjusted model. CI, confidence interval.

Prevalence of Heart Failure and Temporal Trends

In total, 300,241 (32.4%) individuals who commenced dialysis had a recorded diagnosis of CHF. The overall prevalence varied from 31% to 34% throughout the study period (Table 3). CHF was more prevalent among women than men and increased significantly with advancing age. For women age 18 to 50 years, the prevalence of CHF increased significantly from 14% in 1995 to 17% in 2005, whereas for women age 50 to 70 and >70 years, the prevalence of CHF was greatest at 47% in 1997 and decreased thereafter. For men, the pattern was similar to women but with higher prevalence estimates across all age categories.

Table 3.

Temporal trends in the prevalence of heart failure at dialysis onset among US dialysis patients 1995 to 2005

| 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall population (n = 300,241) | 31 | 32 | 34 | 33 | 32 | 33 | 32 | 31 | 32 | 32 | 34 |

| Men (n = 154,950) | |||||||||||

| overall | 28 | 31 | 32 | 32 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 30 | 31 | 31 | 33 |

| age subgroup (years) | |||||||||||

| 18 to 50a | 12 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 50 to 70a | 30 | 33 | 33 | 32 | 31 | 31 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 32 |

| >70a | 41 | 42 | 43 | 43 | 42 | 42 | 41 | 41 | 41 | 41 | 43 |

| Women (n = 145,291) | |||||||||||

| overall | 33 | 35 | 36 | 35 | 33 | 34 | 34 | 33 | 33 | 34 | 35 |

| age subgroup (years) | |||||||||||

| 18 to 50a | 14 | 15 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 50 to 70a | 35 | 36 | 36 | 35 | 33 | 34 | 33 | 33 | 32 | 32 | 33 |

| >70a | 43 | 45 | 47 | 45 | 43 | 44 | 43 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 |

P < 0.001 for comparisons for prevalence of congestive heart failure across calendar years.

Crude Mortality Rates and Temporal Trends

The median follow-up for the entire cohort was 1.9 years: 562,305 (60.7%) patients died, 105,565 (11.4%) were transplanted, and 7337 (0.79%) patients were lost to follow-up. The overall mortality was significantly higher among CHF (n = 223,234, 74.4%) patients than without CHF (n = 339,071, 54.2%) and remained significant after multivariable adjustment (RR = 1.22, 95% CI 1.21 to 1.23). From 1995 to 2005, crude mortality rates from CHF increased significantly from 342 to 394 per 1000 person-years in men and from 331 to 383 per 1000 person-years in women (Table 4). Within gender and age categories, there were noticeable differences. For men, age-specific mortality rates decreased for patients 50 to 70 and 18 to 50 years old but increased for patient >70 years old during the study period. Similarly, for women, mortality rates decreased for patients 50 to 70 years old and increased for patients >70 years old whereas no significant changes were observed for patients 18 to 50 years old.

Table 4.

Mortality rates among men and women with diagnosed heart failure in the US dialysis population 1995 to 2005

| Overall Mortality Rates | Deaths per 1000 Person Years |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | |

| Men (n = 114,070) | |||||||||||

| all | 342 | 352 | 356 | 355 | 353 | 355 | 350 | 356 | 350 | 355 | 394 |

| age-specific | |||||||||||

| 18 to 50 yearsa | 167 | 167 | 163 | 160 | 157 | 151 | 142 | 157 | 137 | 147 | 159 |

| 50 to 70 yearsa | 304 | 302 | 298 | 293 | 289 | 285 | 274 | 272 | 256 | 249 | 279 |

| >70 yearsa | 484 | 518 | 529 | 522 | 518 | 522 | 519 | 514 | 525 | 537 | 577 |

| Women (n = 109,164) | |||||||||||

| all | 331 | 337 | 347 | 346 | 352 | 347 | 339 | 337 | 344 | 344 | 383 |

| age-specific | |||||||||||

| 18 to 50 years | 177 | 182 | 176 | 167 | 180 | 176 | 164 | 156 | 180 | 161 | 173 |

| 50 to 70 yearsa | 291 | 290 | 290 | 290 | 285 | 276 | 264 | 263 | 255 | 256 | 268 |

| >70 yearsa | 447 | 460 | 480 | 476 | 490 | 481 | 472 | 463 | 481 | 476 | 534 |

P < 0.001 for comparisons of incident death rates across calendar years.

Mortality Risks for Men and Women with CHF at Dialysis Onset

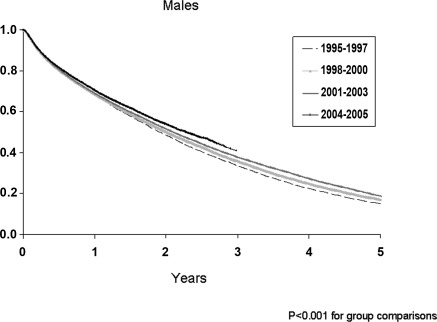

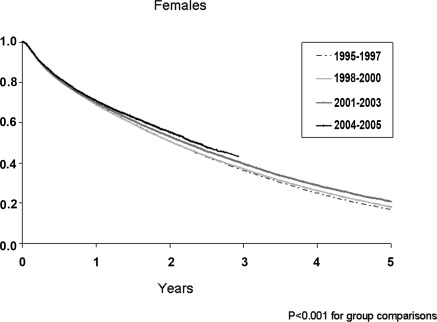

The adjusted survival curves for men and women with CHF, stratified by incident year, are illustrated in Figures 1 and 2. Overall survival was greater for successive incident cohorts (P < 0.001). Unadjusted and adjusted mortality risks for each incident year cohort are illustrated in Table 5. For men, unadjusted mortality risks in years 1995 to 1999 and 2001 to 2002 were not different from those who started in 2000 (referent, RR = 1.00). However, for more recent cohorts, mortality risks were significantly lower in 2003, 2004, and 2005 (RR = 0.96, 95% CI 0.93 to 0.98; RR = 0.94, 95% CI 0.91 to 0.97; and RR = 0.95, 95% CI 0.93 to 0.98, respectively). With adjustment for age, comorbid conditions, lifestyle factors, and laboratory variables a trend of decreasing mortality risk ratios was observed from 1995 to 2005. In the fully adjusted model, mortality risks were greatest for patients in 1995 (RR = 1.06, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.11) and lowest for patients in 2005 (RR = 0.91, 95% CI 0.87 to 0.96) compared with the referent year 2000. For women, the pattern of mortality was similar to men. Compared with the referent, the relative adjusted mortality risks were significantly higher for women who began dialysis therapy in the years 1995 to 1999 (RR = 1.06, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.10 in 1995) compared with those who began dialysis in the years 2001 to 2005 (RR = 0.90, 95% CI 0.85 to 0.95 in year 2005). Temporal trends in mortality were also conducted across age categories. For men, the average reduction in mortality was 3%/yr for those 18 to 50 and 50 to 70 years of age and 1% for patients >70 years (P for trend < 0.001). For women, the pattern was similar but less impressive, with women >70 years of age experiencing a marginal (<0.5%) decrease in mortality per year (P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Adjusted Cox survival curves for men with congestive heart failure (CHF) by grouped years of incidence (1995 to 1997, 1998 to 2000, 2001 to 2003, 2004 to 2005). Adjusted for age at study start, race, diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular and cerebrovascular disease, current tobacco use, chronic lung disease, neoplasm, alcohol dependence, body mass index, serum albumin, hematocrit, estimated GFR, and predialysis erythropoietin use. P < 0.001 for all group comparisons.

Figure 2.

Adjusted Cox survival curves for women with CHF by grouped years of incidence (1995 to 1997, 1998 to 2000, 2001 to 2003, 2004 to 2005). Adjusted for age at study start, race, diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular and cerebrovascular disease, current tobacco use, chronic lung disease, neoplasm, alcohol dependence, body mass index, serum albumin, hematocrit, estimated GFR, and predialysis erythropoietin use. P < 0.001 for all group comparisons.

Table 5.

Relative mortality risks for men and women with diagnosed heart failure in the US dialysis population 1995 to 2005

| RR Death | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | |||||||||||

| unadjusted | 0.98 (0.95 to 1.01) | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.02) | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.04) | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.03) | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.03) | 1.00 referent | 0.98 (0.96 to 1.00) | 0.99 (0.96 to 1.01) | 0.96 (0.93 to 0.98) | 0.94 (0.91 to 0.97) | 0.95 (0.93 to 0.98) |

| adjusted for age | 1.01 (0.97 to 1.04) | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.06) | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.06) | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.04) | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.03) | 1.00 referent | 0.98 (0.95 to 1.00) | 0.97 (0.95 to 1.00) | 0.95 (0.92 to 0.97) | 0.93 (0.91 to 0.96) | 0.94 (0.92 to 0.97) |

| adjusted for alla | 1.06 (1.02 to 1.11) | 1.09 (1.05 to 1.13) | 1.08 (1.05 to 1.12) | 1.06 (1.02 to 1.09) | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.06) | 1.00 referent | 0.99 (0.96 to 1.02) | 0.97 (0.94 to 1.00) | 0.95 (0.92 to 0.98) | 0.92 (0.89 to 0.95) | 0.91 (0.87 to 0.96) |

| Women | |||||||||||

| unadjusted | 0.96 (0.93 to 0.99) | 0.97 (0.95 to 1.00) | 1.00 (0.97 to 1.03) | 1.00 (0.97 to 1.02) | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.04) | 1.00 referent | 0.98 (0.95 to 1.00) | 0.96 (0.94 to 0.99) | 0.97 (0.94 to 0.99) | 0.94 (0.91 to 0.97) | 0.95 (0.92 to 0.98) |

| adjusted for age | 0.99 (0.96 to 1.02) | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.02) | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.04) | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.03) | 1.02 (1.00 to 1.05) | 1.00 referent | 0.97 (0.95 to 1.00) | 0.95 (0.93 to 0.98) | 0.96 (0.93 to 0.99) | 0.93 (0.90 to 0.95) | 0.94 (0.91 to 0.97) |

| adjusted for alla | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.10) | 1.07 (1.03 to 1.10) | 1.05 (1.01 to 1.08) | 1.05 (1.02 to 1.09) | 1.04 (1.00 to 1.07) | 1.00 referent | 0.97 (0.94 to 1.00) | 0.95 (0.92 to 0.99) | 0.96 (0.93 to 0.99) | 0.92 (0.89 to 0.96) | 0.90 (0.85 to 0.95) |

Data presented as relative risk of death (RR) and 95% confidence interval.

Final multivariable model adjusted for demographic (age, race), clinical (diabetes, hypertension, coronary disease, chronic pulmonary disease, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, pulmonary disease, cancer, body mass index, and predialysis erythropoietin use) functional (difficulty in walking), lifestyle (current tobacco use and alcohol dependence,) and laboratory factors (serum albumin, hematocrit, and estimated GFR at dialysis initiation).

Discussion

In this national cohort study, we found that the overall prevalence of CHF among patients at the start of dialysis has remained remarkably stable over the previous decade in men and women despite changing demographic profiles. The overall prevalence was higher in women than men and increased with advancing age throughout the period of observation. Furthermore, although the overall survival was poorer in patients with CHF than without, the survival of CHF patients has improved from 1995 to 2005 despite changing patterns in demographic and comorbidity profiles. In general, the magnitude of these improvements was modest—similar for men and women and greater in younger than older patients.

Prior studies have demonstrated a high prevalence of CHF and other cardiovascular conditions among incident dialysis cohorts (1–4). However, information on the temporal trends in CHF prevalence and its effect on clinical outcomes over time are lacking. This study provides new insights into the epidemiology of CHF in a high-risk population. First, although the overall prevalence of CHF was remarkably stable throughout the study period, a trend of increasing prevalence was found in younger patients whereas a trend of decreasing prevalence was present in older patients, at least from 1997 onward. Second, the prevalence of CHF was substantially higher in women than men, a finding that persisted throughout the 10-year study and contrasts with findings from the general population (22,23). The differences in prevalence patterns between women and men may well be explained by better survival of women over men with heart failure in the general population, greater acceptance of women with CHF for dialysis than men, or other as yet unidentified mechanisms (24). It is also possible that selective differences in access to diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for CHF as well as differences in overall acceptance rates for dialysis may account for these findings.

The study presented here is the first to report secular trends in survival of patients with CHF at dialysis onset. The most striking observation from this study is the noticeable improvement in survival across all age and gender subgroups. Although the unadjusted model suggested modest improvement in survival experiences for more recent cohorts (2003 to 2005) compared with earlier cohorts (1995 to 1999), the fully adjusted model confirmed even greater reductions in relative mortality risks from 1995 to 2005 despite worsening demographic and comorbidity profiles. The pattern of mortality reduction was similar in men and women but differed in magnitude across age groups. On average, the reductions in adjusted mortality were greatest for younger men and women (approximately 2% to 3% lower per year) whereas the reductions in mortality were more modest for older patients with CHF (between 0.5% and 1% lower per year).

The reasons that underpin these positive survival trends for new dialysis patients with CHF are unclear and are likely multifactorial. Whether improvements in survival were related to temporal improvements in the provision of overall kidney disease care or represented selective improvements in elements of delivered cardiovascular care is uncertain (6–14). One could speculate that better management of patients with chronic kidney disease before and after dialysis onset may have contributed to these encouraging results over the last decade. In support of this, our analysis demonstrated that more recent incident cohorts with CHF had better anemia management, greater use of erythropoietin (an indicator of good predialysis care), and were more likely to be initiated on dialysis earlier—factors that may have contributed to better overall survival. It is also reasonable to suggest that improvements in dialysis practices after the initiation of dialysis may have contributed to these survival benefits. Improved anemia management, dialysis delivery, and greater use of evidence-based guidelines have been demonstrated in several studies over the past decade (15–17). On the other hand, it is also tempting to speculate that selective improvements in cardiovascular practices, especially those that relate to earlier diagnosis and more effective treatment strategies of CHF, may also have had a beneficial effect (6,7,9,10). Recent studies have demonstrated greater use of diagnostic and interventional strategies for cardiovascular disease in patients with advanced kidney disease nearing dialysis and receiving dialysis therapy (11,25,26).

The findings reported here should be considered in the context of an observational cohort study and its inherent limitations. A potential concern is the underreporting of specific comorbid conditions present in new dialysis patients from the CMS Medical Evidence Form (19,20). For example, previous comparisons of prevalence between the CMS Medical Evidence Form and the Choices for Health Outcomes in Caring for ESRD cohort study found a significantly lower prevalence of CHF (30% versus 44%) and suggested an underreporting on the basis of medical chart abstraction. However, the inclusion of episodes of pulmonary edema as part of the diagnostic criteria for CHF may have inflated the true prevalence (20). Indeed, we recognize the difficulties in clinical practice in differentiating an episode of heart failure due to “true cardiac impairment” from an episode of volume overload due to advanced kidney failure. In the ideal setting, confirmation of all heart failure episodes should be based on objective clinical criteria supported with radiologic and echocardiographic evidence as demonstrated by Harnett et al. (1). In this prospective cohort study, the prevalence of CHF was 31%, virtually identical to our estimate in 1995. We also acknowledge the limitations of observational studies in identifying cause and effect associations. Although we adjusted for several well known predictors of mortality, it is possible that other relevant factors such as the severity of comorbid conditions and the quality of delivered care omitted from the model may completely or partly explain the effect of calendar year on subsequent mortality. Finally, we submit that the study presented here is no substitute for well designed prospective studies that can accurately characterize the natural history and clinical outcomes of a specific disease.

However, this study has several important and unique strengths. First, its large sample size permitted estimates of prevalence and survival across all gender and age subgroups in consecutive national cohorts. Second, it is unique in its design in that the study is a virtual census of all new dialysis patients in the United States, thus providing excellent generalizability (10). Third, the recording of several demographic, clinical, laboratory, and lifestyle characteristics of patients provided a well characterized population and permitted a comprehensive adjustment for case mix. Finally, the outcome measure of survival is based on well validated instruments that have been used in previous studies of this nature (4,5,9).

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the overall burden of CHF among incident dialysis patients is high and has not changed significantly over the past decade in the United States. It highlights the unequal distribution of CHF among men and women and across age groups. Importantly and encouragingly, it demonstrates for the first time that improvements in survival have occurred from 1995 to 2005, albeit modest, across all gender and age categories and that these trends are independent of changing demographic and comorbidity profiles. These findings would suggest that over the past decade, efforts to reduce the mortality associated with CHF in dialysis patients have been successful. Further advances in prevention and treatment of CHF in this population along with continued national surveillance of prevalence and outcomes are required to sustain the goal of improving outcomes for these high-risk patients.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Stack and Dr. Nguyen had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and data analysis. Drs. Stack and Nguyen collaborated on the study design and analysis and editing of the final manuscript. Drs. Mohammad and Hanley contributed to the data interpretation and final manuscript. All work was performed at the Regional Kidney Centre of Letterkenny General Hospital Donegal, a university affiliate of the National University of Ireland Galway, Ireland. Dr. Stack was supported by a National Scientist Development Grant (0335317N) from the American Heart Association and the Renal Educational Research Fund, Letterkenny General Hospital. Part of this material was presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology; November 4 through 9, 2008; Philadelphia, PA. The data reported here have been supplied by the USRDS. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as the official policy or interpretation of the US government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Access to UpToDate on-line is available for additional clinical information at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1. Harnett JD, Foley RN, Kent GM, Barre PE, Murray D, Parfrey PS: Congestive heart failure in dialysis patients: Prevalence, associations, prognosis and risk factors. Kidney Int 47: 884–890, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stack AG, Bloembergen WE: A Cross-sectional study of the prevalence and clinical correlates of congestive heart failure among incident US dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 2001. 38: 992–1000, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schreiber BD: Congestive heart failure in patients with chronic kidney disease and on dialysis. Am J Med Science 325: 179–193, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Comorbid conditions and correlations with mortality risk among 3,399 incident Hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 20: 32–38, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. U.S Renal Data System: Causes of death. Am J Kidney Dis 34[Suppl 1]: S87–S94, 1999. 10431005 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Silverberg DS, Wexler D, Blum M, Schwartz D, Wollman Y, Iaina A: Erythropoietin should be part of congestive heart failure management. Kidney Int Suppl 87: S40–S47, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cice G, Ferrara L, D'Andrea A, D'Isa S, Di Benedetto A, Cittadini A, Russo PE, Golino P, Calabrò R: Carvedilol increases two-year survival in dialysis patients with dilated cardiomyopathy: A prospective, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 41: 1438–1444, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cice G, Di Benedetto A, D'Isa S, D'Andrea A, Marcelli D, Gatti E, Calabrò R: Effects of telmisartan added to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on mortality and morbidity in hemodialysis patients with chronic heart failure: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 56: 1701–1708, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stack AG, Molony DA, Rahman NS, Dosekun A, Murthy B: Impact of dialysis modality on survival of new ESRD patients with congestive heart failure in the United States. Kidney Int 64: 1071–1079, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ganesh SK, Hulbert-Shearon T, Port FK, Eagle K, Stack AG: Mortality differences by dialysis modality among incident ESRD patients with and without coronary artery disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 415–424, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. US Renal Data System: USRDS 2009 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institute of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chan C, Floras JS, Miller JA, Pierratos A: Improvement in ejection fraction by nocturnal haemodialysis in end-stage renal failure patients with coexisting heart failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 17: 1518–1521, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sehgal AR, Leon JB, Siminoff LA, Singer ME, Bunosky LM, Cebul RD: Improving the quality of hemodialysis treatment: A community-based randomized controlled trial to overcome patient-specific barriers. JAMA 287: 1961–1967, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sugarman JR, Frederick PR, Frankenfield DL, Owen WF, Jr, McClellan WM: Developing clinical performance measures based on the Dialysis Outcomes Quality Initiative Clinical Practice Guidelines: Process, outcomes, and implications. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 806–812, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wolfe RA, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Ashby VB, Mahadevan S, Port FK: Improvements in dialysis patient mortality are associated with improvements in urea reduction ratio and hematocrit, 1999 to 2002. Am J Kidney Dis 45: 127–135, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McClellan WM, Hodgin E, Pastan S, McAdams L, Soucie M: A randomized evaluation of two health care quality improvement program (HCQIP) interventions to improve the adequacy of hemodialysis care of ESRD patients: Feedback alone versus intensive intervention. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 754–760, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, Kausz AT, Levin A, Steffes MW, Hogg RJ, Perrone RD, Lau J, Eknoyan G: National Kidney Foundation. National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med 139: 137–147, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. K/DOQI Workgroup: K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 45[Suppl 3]: S1–153, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. US Renal Data System: Patient characteristics at the start of ESRD: Data from the HCFA Medical Evidence Form. Am J Kidney Dis 34: S63–S73, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Longnecker JC, Coresh J, Klag MJ, Levey AS, Martin AA, Fink NE, Powe NR: Validation of comorbid conditions on the end-stage renal disease medical evidence report: The CHOICE study. Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 520–529, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Levey AS, Bosch JP, Breyer Lewis J, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D: A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Ann Intern Med 130: 461–470, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mosterd A, Hoes AW, de Bruyne MC, Deckers JW, Linker DT, Hofman A, Grobbee DE: Prevalence of heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction in the general population: The Rotterdam Study. Eur Heart J 20: 447–455, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McCullough PA, Philbin EF, Spertus JA, Kaatz S, Sandberg KR, Weaver WD: Confirmation of a heart failure epidemic: Findings from the Resource Utilization among Congestive Heart Failure (REACH) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 39: 60–69, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Parashar S, Katz R, Smith NL, Arnold AM, Vaccarino V, Wenger NK, Gottdiener JS: Race, gender, and mortality in adults ≥65 years of age with incident heart failure (from the Cardiovascular Health Study). Am J Cardiol 103: 1120–1127, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Herzog CA, Solid CA: Long-term survival of US dialysis patients after surgical bypass or percutaneous coronary stent placement in the drug-eluting stent era. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 11A, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Herzog CA, Gilbertson DT: Comparative long-term survival of general Medicare patients with surgical versus percutaneous coronary intervention in the era of drug-eluting stents and the impact of chronic kidney disease. Circulation 118[Suppl 2]: S741A, 2008 [Google Scholar]