Abstract

Resveratrol, a stilbenic compound deriving from the phenyalanine/polymalonate route, being stilbene synthase the last and key enzyme of this pathway, recently has become the focus of a number of studies in medicine and plant physiology. Increased demand for this molecule for nutraceutical, cosmetic and possibly pharmaceutic uses, makes its production a necessity. In this context, the use of biotechnology through recombinant microorganisms and plants is particularly promising. Interesting results can indeed arise from the potential of genetically modified microorganisms as an alternative mechanism for producing resveratrol. Strategies used to tailoring yeast as they do not possess the genes that encode for the resveratrol pathway, will be described. On the other hand, most interest has centered in recent years, on STS gene transfer experiments from various origins to the genome of numerous plants. This work also presents a comprehensive review on plant molecular engineering with the STS gene, resulting in disease resistance against microorganisms and the enhancement of the antioxidant activities of several fruits in transgenic lines.

1. Introduction

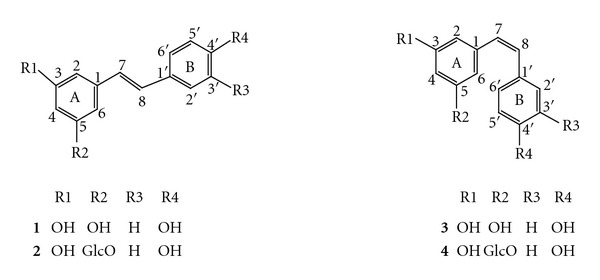

Hydroxystilbenes (hereafter referred to as stilbenes) are natural phenolic compounds occurring in a number of plant families including Vitaceae, Dipterocarpaceae, Gnetaceae, Pinaceae, Poaceae, Fabaceae, Leguminoseae, and Cyperaceae [1]. Although polyphenolic compounds display an enormous chemical diversity, stilbenes seem to constitute a rather restricted group of molecules, the skeleton of which is based on resveratrol especially in Vitaceae and Fabaceae (Figure 1) [2]. Resveratrol is one of the most extensively studied natural products, doubtless for its large spectrum of biological activities in human health as a cardioprotective, an antitumor, a neuroprotective, and an antioxidant agent. Some of the resveratrol's properties have been associated with the benefits of a moderate consumption of red wine. Many roles have also been ascribed to resveratrol and its derivatives (Figure 1) in plants; namely, they constitute antimicrobial, deterrent or repellent compounds acting as allelochemicals or phytoalexins, protecting them from attacks by fungi, bacteria, nematodes, or herbivores [3–5].

Figure 1.

Molecular structures of trans- and cis-resveratrol 1 and 3, and trans- and cis-piceid, 2 and 4, respectively (GlcO = β-D-glucose).

According to these potential activities in plants and humans, the interest for resveratrol has increased. Currently, rising demand for resveratrol and derivatives for nutraceutical, cosmetic, and putatively pharmaceutical uses makes their production a necessity. Metabolic engineering for resveratrol production thus has significant commercial value. As all the genes encoding enzymes responsible for resveratrol biosynthesis have been cloned and characterized in detail, this makes molecular engineering of this compound relatively straightforward.

Most interest has now centered upon metabolic engineering of resveratrol in plants with the objectives of increasing tolerance of the latter to pathogenic microorganisms and improving the nutritional quality of food products through the expression of pharmaceutically active compounds in plants incapable of synthesizing resveratrol.

Microorganisms can also be used to heterologously express the resveratrol biosynthetic pathway to obtain this compound in valuable amounts. In this paper, we will discuss the potential of tailored microorganisms, specifically yeast, and plants for resveratrol production.

2. Resveratrol in Health and Disease

Resveratrol was identified in 1940 as a constitutive compound of the roots of white hellebore (Veratrum grandiflorum) [6]. Resveratrol is also present in high amounts in the roots of Polygonum cuspidatum used in traditional Chinese and Japanese medicine, and this compound was acclaimed for its wondrous effects for the treatment of human fungal diseases (suppurative dermatitis, gonorrhea favus, and athlete's foot), hyperlipidemia, atherosclerosis, or inflammations. Moreover, resveratrol recently has been shown to be a potent therapeutic agent [7–10].

First, there is considerable evidence that resveratrol acts both as a free radical scavenger [11, 12] and a potent antioxidant doubtless for its ability to promote the activities of numerous antioxidative enzymes [12, 13]. Resveratrol inhibits lipid peroxidation which is an indicator of possible free radical damage to cellular membranes [14, 15]. Resveratrol may operate in a number of antioxidant mechanisms leading to the development of atherosclerosis, protecting, for example, LDL molecules against peroxidation [16–18] or reactive oxygen species production by blood platelets [19]. There is however some evidence that resveratrol exhibits pro-oxidant activity under certain experimental conditions (in the presence of copper ions) [20], causing oxidative DNA damage that may lead to cell cycle arrest or apoptosis [21].

Resveratrol is also considered as an antiproliferative agent for cancer [22], exerting an antitumor activity either as a cytostatic or as a cytotoxic agent in various types of cancer. Resveratrol induces cell death through positive induction of death receptor-mediated apoptosis [23–25], mitchondria-mediated apotosis [26], and nuclear (transcription) factor-mediated apotosis [27, 28].

Refractory disease and poor prognosis in many tumors have been related with high expression of antiapoptotic molecules such as survivin; resveratrol was proven to act at this level through survivin depletion [29]. Similarly, numerous works showed that resveratrol is a potent inhibitor of cell cycle progression, causing G1 phase arrest [30], inhibiting G0-G1 transition in human lymphocyte [31] or perturbing progression through S and G2 phases in cultured bovine artery endothelial cell proliferation [32]. Since the pioneering work of the group of Pezzuto [33], affording for the very first time evidence for the cancer chemoprotective activity of resveratrol on HL-60 and Hepa 1clc7 cells, many other models of human cancers were used, confirming these findings. The most frequently described mode of action for resveratrol concerns apoptosis (see above), the response depending on the expression of the tumor suppressor gene p53. A number of related factors can be modulated by resveratrol, such as activation of caspases, decreases in the antiapoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL [34, 35], increases in the proapoptotic proteins Bax [36], inhibition of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases, that is, proteins implicated in cell cycle progression [32, 37], and interference with nuclear transcription factor kappa B (NF-κB)—and activator protein 1 (AP-1)—mediated cascades.

Most importantly, there are several works concerning both the antitumor effects and the antitumor mechanisms of resveratrol in vivo. In several studies, it was shown, namely, that resveratrol inhibits the development of skin cancer in vivo by topical applications, causing a significant reduction of the tumor diameter and the tumor incidence [33, 38, 39]. Moreover, resveratrol significantly inhibits the UV-B-mediated increase in skin thickness and skin edema [40]. On the other hand, resveratrol was proven not to be very effective in inhibiting the progression of leukemia in vivo, even when high doses were used [41], despite its antileukemic activity in vitro and though resveratrol can be converted to the known antileukemic related stilbene, piceatannol [42]. In regard to breast cancer, resveratrol was shown to reduce N-methyl-N-nitrosourea-induced mammary tumorigenesis in female rats at high doses (100 mg/kg body weight) though being uneffective at lower doses (10 mg/kg body weight) [43]. Otherwise, some authors have shown that resveratrol glucosides, namely, piceid (a 3-O-β-D-resveratrol glucoside), administered orally or intraperitoneally to mice, reduced tumor volume, tumor weight, and metastasis in lung carcinoma [44, 45]. A few investigations about the antitumor effects of resveratrol and derivatives against liver cancers have been reported to date, showing that this compound administered orally or intraperitoneally to rats caused a 25% reduction in tumor cell numbers and restrained hepatoma cell invasion but not proliferation [46, 47]. Finally, orally administration of resveratrol to mice was shown to prevent colonic tumor formation and reduce small intestinal tumors by 70% [48].

Neurologic benefits of resveratrol described experimentally concern the following diseases: cerebral ischemia in rats [49, 50], amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [51], Parkinson's disease in rats [52], spinal cord lesions in rabbits [53], brain edema and tumors in human cells [54], seizure in rats [55–57], pain and cognitive impairment in rats [58, 59]. According to Doré [60], the neuroprotective effects of resveratrol could be mediated by regulation of the heme oxygenase antioxidant systems in neurons, especially in case of age-related vascular dementia and Alzheimer's disease [61].

There are several mechanisms to support resveratrol as a cardioprotective agent such as inhibition of LDL peroxidation, reduction of the degree of neointimal hyperplasia and restenosis, inhibition of platelet aggregation together with chemoprevention of atherosclerogenesis. Resveratrol was proven to inhibit LDL peroxidation via antioxidant and free scavenging activities in ex vivo rat heart studies [62] and circumstantial evidence of its potent role in preventing atherosclerogenesis could thus be given [63, 64]. Resveratrol was shown to inhibit neointimal hyperplasia in several animal studies and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation in a rabbit model of restenosis [65, 66] and to block platelet aggregation from high-cholesterol-fed rabbits [67].

Resveratrol exerts some activities against a range of bacteria affecting humans (Chlamydia pneumonia, the cause of human acute respiratory tract infections [68], and Helicobacter pylori, the main agent responsible for chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer disease [69, 70]). Resveratrol also inhibited the growth of several bacteria known to be major agents of human skin infections such as Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [71]. Similarly, resveratrol completely inhibits the growth of Neisseria gonorrhoeae (responsible for the sexually transmitted disease gonorrhoea) [72]. Stilbenes generally also have biocidal activities against plant fungal pathogens (namely, Botrytis cinerea, the causal organism for gray mold, Pyricularia oryzae, the agent of pyriculariosis, Plasmopara viticola, the causal agent for downy mildew [73–77], fungi associated with esca of grapevine [78]), and human fungal pathogens such as Candida albicans, an agent of candidiasis [79].

Finally, resveratrol has been shown to extend the lifespan of lower organisms, yeast [80], and metazoans [81], via the sirtuin/Sir2 family. More recently, a study has confirmed the conservation of these preventive and protective mechanisms controlling lifespan extension in higher organisms such as mice [82]. Using a similar approach, other works reached the same conclusions with regard to the protective effects of resveratrol against diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance [7, 82].

Otherwise, DNA-damaging products can induce premature senescence in cancer cells, limiting tumor development. However, senescent cancer cells may reenter the cell cycle and lead to tumor relapse. Recently, resveratrol was remarked by its ability to induce DNA damage in cancer cells. In fact, resveratrol suppressed viability and induced DNA damage in human head and neck squamous carcinoma cells [83]. Similarly, human squamous cancer cells treated with resveratrol were shown to express oxidative stress-mediated DNA damage [84].

3. Biosynthesis of Resveratrol

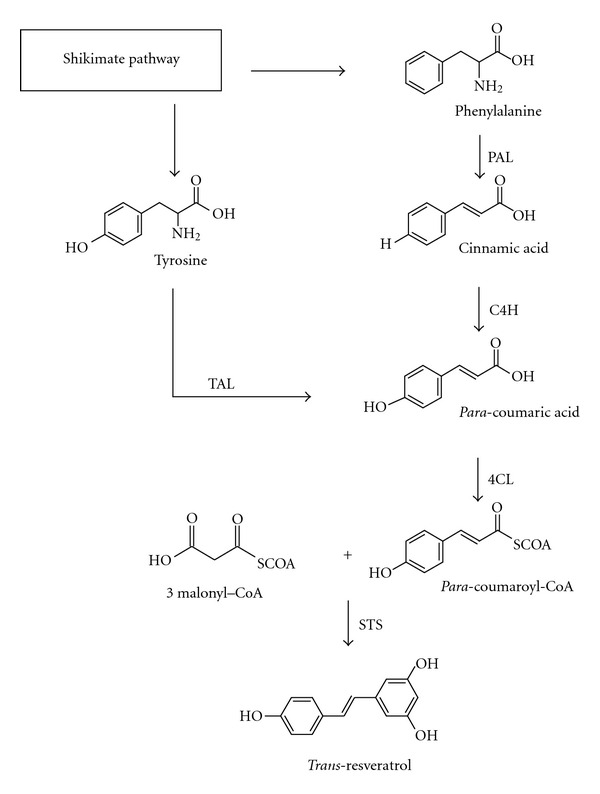

Stilbene phytoalexins, as flavonoid-type phytoalexins, are formed on the phenylalanine/polymalonate route, being the last step of this biosynthesis pathway catalyzed by stilbene synthase (STS) (Figure 2). Trans-resveratrol can be synthesized either starting with phenylalanine or from tyrosine, both pathways giving rise to para-coumaric acid through, respectively, the phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) and the cinnamate 4 hydroxylase (C4H), or directly through the tyrosine ammonia lyase (TAL). A para-coumaric-acid coenzyme A ligase (4CL) transforms the para-coumaric acid into para-coumaroyl-CoA, which then leads to trans-resveratrol after condensation with three molecules of malonyl-CoA through STS activity [85]. STS belongs to the so-called type III of the polyketide synthase enzyme superfamily, a class of enzymes which carry out iterative condensation reactions with malonyl-CoA. [86, 87]. Resveratrol synthesis is induced in plants as a response to fungal infection [73, 74, 88], abiotic stresses (UV irradiation, metallic salts, methyl jasmonate) [89–93] as well as to natural compounds eliciting plant defense responses [94, 95] or nonpathogenic rhizobacteria [96, 97].

Figure 2.

Biosynthesis of resveratrol via the phenylalanine/polymalonate pathway. PAL, phenylalanine ammonia lyase; TAL, tyrosine ammonia lyase; C4H, cinnamate-4-hydroxylase; 4CL, para-coumaric acid: coenzyme A ligase; STS, stilbene synthase.

STS is encoded by a multigene family mainly comprising the resveratrol-forming STS genes from grapevine (pSV21, pSV25, pSV696, pSV368, and StSy) [98], (Vst1, Vst2, Vst3) [99], the AhRS gene from Arachis hypogea [100], and an STS-encoding gene from Parthenocissus henryana [101]. Other STS genes have also been isolated from pine [102–104], together with a stilbene synthase gene from Vitis riparia cv Gloire de Montpellier [105]. The Sb STS1 gene isolated from Sorghum is at present the only one STS gene described in a Monocotyledonous plant [106]. Knowledge of the resveratrol biosynthetic route thus paves the way for metabolic engineering in microorganisms or plants.

4. Tailoring Yeast for Resveratrol Biosynthesis

Microorganisms are widely used biological systems whose engineering may be useful for the production of numerous valuable molecules and can lead to interesting applications for example in the wine industry [107–109]. Engineering bacteria or yeast for resveratrol might thus represent a valuable means of its production in large quantities. Their tailoring is necessary because microorganisms do not possess the genes that encode for the resveratrol pathway. In this paper, we will focus only on yeast tailoring for resveratrol production. Two main strategies have already been used to that end: (i) introducing the entire biosynthetic pathway using aromatic amino acids as substrates (L-phenylalanine or L-tyrosine) [110–113] and (ii) introducing specific genes, such as para-coumaroyl-CoA ligase and stilbene synthase, starting with para-coumaric acid as a substrate (Figure 2) [114–120].

4.1. Engineering the Entire Pathway

To obtain resveratrol from its precursors L-phenylalanine or L-tyrosine on the phenylpropanoid route appears to be the most promising option in terms of production cost. The entire resveratrol pathway has been introduced successfully into the oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica (ATCC 20362 strain) with the genes encoding for phenylalanine/tyrosine ammonia lyase (PAL/TAL), cinnamate-4-hydroxylase (4CH), para-coumaroyl-CoA ligase (4CL), and stilbene synthase (STS) activities [110] (Table 1). Metabolic engineering was completed by constitutive expression of malonyl CoA, a precursor for both naringenin-chalcone, the first C15 intermediate in the flavonoid route, and stilbene synthesis. Genes that encode for each required enzyme from different plant species (grapevine, peanuts) have been tested. In the best performing yeast, genes that encode for the PAL and TAL from Rhodotorula glutinis, the 4CL from Streptomyces coelicolor, and an STS from Vitis sp. have been used, and the resulting production of resveratrol reached in this system 1.46 mg/L [110].

Table 1.

Metabolic engineering of resveratrol in yeast.

| Microorganisms/species | Introduced gene(s) | Origin of genes | Resveratrol quantity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast Yarrowia lipolytica | PAL/TAL, C4H, 4CL, STS | Rhodotorula glutinis (PAL/TAL), Streptomyces coelicolor (4CL), Vitis sp. (STS) | 1.46 mg/L | [110] |

| Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae | PAL, C4H, 4CL, STS | Arabidopsis thaliana (PAL, C4H, 4CL), Rheum tataricum (STS) | not detectable | [111] |

| Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae | TAL, 4CL::STS fusion protein | Rhodobacter sphaeroides (TAL), Arabidopsis thaliana (4CL), Vitis vinifera (STS) | 5.25 mg/L | [116] |

| Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 4CL, STS | Populus trichocarpa×Populus deltoides (4CL), Vitis vinifera (STS) | 1.45 mg/L | [114] |

| Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 4CL, STS | Nicotiana tabacum (4CL), Vitis vinifera (STS) | 5.8 mg/L | [115] |

| Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 4CL1, STS | Arabidopsis thaliana (4CL), Vitis vinifera (STS) | 262–391 mg/L | [117] |

| Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae with phenylalanine | PAL, CPR, C4H, 4CL, STS | Populus trichocarpa×P. deltoides (PAL, CPRa) Glycine max (C4H, 4CL), Vitis vinifera (STS) | 0.29 mg/L | [113] |

| Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae with para-coumaric acid | PAL, CPR, C4H, 4CL, STS | Populus trichocarpa×P. deltoides (PAL, CPR) Glycine max (C4H, 4CL), Vitis vinifera (STS) | 0.31 mg/L | [113] |

| Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae | TAL, 4CL::STS fusion protein, araE transporter | Rhodobacter sphaeroides (TAL), Escherichia coli (araE), Arabidopsis thaliana (4CL), Vitis vinifera (STS) | 3.1 mg/L 1.27 mg/L (without the araE transporter) | [119] |

| Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae | TAL, 4CL::STS fusion protein | Rhodobacter sphaeroides (TAL), Arabidopsis thaliana (4CL), Vitis vinifera (STS) | 14.4 mg/L | [120] |

aCPR: Cytochrome P450 Reductase.

Current efforts to increase resveratrol bioproduction in yeast have focused, so far not surprisingly, on heterologous expression of the genes encoding for the enzymes involved in the phenylpropanoid pathway and for STS, in baker yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae [111, 113–120]. Namely, the entire resveratrol pathway has been introduced in S. cerevisiae (CEN.PK113-5D strain), but also in molds such as Aspergillus niger (FGSC A913 strain) and A. oryzae (MG1363 strain). In these cases, pathway expression started with the PAL enzyme. The ability of tailored S. cerevisiae to produce resveratrol was characterized, but it was not synthesized in measurable amounts in this system. [111]. More recently, Trantas et al. [113] constructed the complete resveratrol biosynthetic pathway in S. cerevisiae to produce resveratrol from phenylalanine. When the medium was supplemented with 10 mM of phenylalanine, the strain produced 0.29 mg/L trans-resveratrol after about 120 h of cultivation. One can thus admit that the introduction of the complete resveratrol pathway in yeast leads to a low production of this compound when compared to some other data obtained in engineered bacteria where resveratrol synthesis can reach up to 100–170 mg/L [121, 122].

4.2. Introducing Selective Genes

An alternative strategy to engineering the entire pathway is directed towards transforming microorganisms with selective genes [114–120] (Table 1). The yeast strain S. cerevisiae FY23 was transformed with both the 4CL and STS genes under utilization of para-coumaric acid as a precursor (added to the culture medium). However, in this system, resveratrol production remained low (1.45 mg/L) [114]. Interestingly, in another study, authors reported that transformation of S. cerevisiae (CEN.PK113-3b strain) with the 4CL gene from tobacco and the STS gene from grapevine enabled it to produce resveratrol in higher quantities (5.8 mg/L) [115]. A S. cerevisiae (WAT11 strain) cotransformed with 4CL and STS constructs and fed with para-coumaric acid only produced 0.65 mg/L resveratrol, but, when the 4CL and the STS-encoding genes that were added to the yeast genome were submitted to protein fusion, yeast expressing 4CL::STS fusion protein exhibited a 10-fold increase in resveratrol production (5.25 mg/L resveratrol) compared to the coexpression of 4CL and STS [116]. This underlines the importance of the spatial localization of these two related enzymes [116]. In another study of the same group [120], authors have utilized a synthetic scaffold to recruit the 4CL1 and STS enzymes of the resveratrol pathway to improve resveratrol production in S. cerevisiae. A 5-fold improvement of the resveratrol production was obtained over the nonscaffolded control, and a 2.7-fold increase (14.4 mg/L within 96 h incubation) was finally observed over the previous reported study with protein fusion [116]. This work clearly demonstrated that synthetic scaffolds can be used for the optimization of engineered metabolic pathway.

Most importantly, it has recently been shown that yeast cells expressing 4CL, STS genes together with the araE gene encoding for a high-capacity Escherichia coli transporter, but with no affinity for resveratrol itself, could enhance resveratrol accumulation. Yeast cells carrying the araE gene produced up to 3.1 mg/L, that is, 2.44-fold higher resveratrol than the control cells [119]. Such an engineered yeast was also proven to increase the resveratrol content in a white wine during the fermentation process [119].

It should be noted that the efficacy of recombinant microorganisms for resveratrol production depends on various factors, such as the species and the strain, the origin of the transferred genes, culture conditions as well as other parameters such as plasmids or precursors used (Table 1). A recent study [117] has shown that fermenting yeast expressing the para-coumaroyl-coenzyme A ligase (4CL1) from Arabidopsis thaliana and the stilbene synthase from Vitis vinifera in a rich medium could considerably improve resveratrol production, rising from a few milligrams per liter to 262 mg/L in rich medium using a laboratory strain. Moreover, resveratrol amounts reached up to 391 mg/L when fermentation was achieved with an industrial Brazilian sugar cane yeast [117].

Taken together, these data indicate that the levels of resveratrol that can be produced by microorganisms remain low, although optimization of the processes might be possible.

5. Tailoring Plants for Resveratrol Biosynthesis

As resveratrol is a potent phytoalexin against plant pathogens and can enhance plant resistance to microbial disease, earlier applications of resveratrol engineering focused primarily on this antimicrobial potential [123, 124]. Tailoring plants for resveratrol synthesis thus constitutes the second aspect of this paper. Particular attention will be given in this section to the choice of the promoters and the enhancer elements used to improve STS transcriptional activity in the transgenes as well as the biological benefits of resveratrol production in terms of enhancement of antioxidant activity in fruits and legumes.

We have seen that tailoring yeast needs the introduction of the entire resveratrol pathway (requiring at least 4 or 5 genes) or the introduction of selective genes (requiring at least 2 genes) depending on the precursor used, phenylalanine or para-coumaric acid. Tailoring plants for resveratrol synthesis appear to be very simple, since STS is a key enzyme of resveratrol synthesis utilizing as substrates precursor molecules that are present throughout the plant kingdom. The introduction of a single gene is thus sufficient to synthesize resveratrol in heterologous plant species. A lot of transformations were then operated to investigate the potential of stilbene biosynthetic genes to confer resistance to pathogens or to increase their nutritional values [123, 124].

5.1. Production of Resveratrol in Transgenic Plants: Gene and Promoter Options

The first gene transfer experiment was performed by the group of Kindl with a complete STS gene from Arachis hypogea introduced into tobacco [100], leading to resveratrol accumulation in response to short-wavelength ultraviolet light. This experiment was then continued by the same group by the transfer of two grapevine STS genes, Vst1 and Vst2, in tobacco, conferring to the plant a higher resistance to Botrytis cinerea infection. This work constitutes the first report of a disease resistance resulting from foreign phytoalexin expression in a novel plant [125]. Since this pioneering work, STS genes have been transferred to a number of plants, including rice [126], barley and wheat [127–130], alfalfa [131], kiwifruit [132], grapevine [133, 134] apple [135, 136], aspen [137], papaya [138], white poplar [139], oilseed rape [140], banana [141], Rehmannia [142] tomato [143–147], Arabidopsis [148], lettuce [101], pea [149], and hop [150] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Metabolic engineering of stilbene synthase in plants, and resulting effects on stilbene levels, resistance to pathogens, and antioxidant activities.

| Plant/species | Introduced gene(s) | Promoter | Produced stilbene(s) | Stilbene quantity (mg/kg of FW) | Biological activity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) | Arachis hypogea STS | Stress-induced promoter | Resveratrol | — | — | [100] |

| Grapevine Vst1 and Vst2 | Stress responsive pVst1 | Resveratrol | 400 | Resistance to Botrytis cinerea | [125] | |

| Chimeric STS gene | Constitutive CaMV 35S | Resveratrol | 50 to 290 | Altered flower morphology, male sterility | [152] | |

| Rice (Oryza sativa L.) | Grapevine Vst1 | Stress responsive pVst1 | — | — | Resistance to Pyricularia oryzae ? | [126] |

| Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) | Grapevine Vst1 | Combination pVst1 +35S enhancer | — | — | Resistance to Botrytis cinerea | [127, 129] |

| Chimeric STS gene | Maize ubiquitin promoter | Resveratrol | 2 | — | [128] | |

| Grapevine Vst1 and Vst2 | Combination pVst1 +35S enhancer | Unknown derivative stilbene compounds | 35 to 190 | Resistance to Puccinia recondita and Septoria nodorum | [130] | |

| Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) | Grapevine Vst1 | Combination pVst1 +35S enhancer | — | — | Resistance to Botrytis cinerea | [127] |

| Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) | Arachis hypogea STS gene (AhRS) | Constitutive CaMV 35S | Piceid | 0.5 to 20 | Resistance to Phoma medicaginis | [131] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana L. | Sorghum SbSTS1 | Constitutive CaMV 35S | Piceid | 584 | — | [106, 148] |

| Kiwi (Actinidia deliciosa) | pSV25 | Constitutive CaMV 35S | Piceid | 20 to 182 | No resistance to Botrytis cinerea | [132] |

| Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) | Grapevine Vst1 | Fungus inducible ms PR 10.1 | Resveratrol | In vitro resistance to Botrytis cinerea | [133] | |

| Vitis pseudoreticulata STS | Constitutive CaMV 35S | Resveratrol | 2.586 | Not determined | [134] | |

| Apple (Malus domestica) | Grapevine Vst1 | Stress responsive pVst1 | Unknown resveratrol-glycoside | — | — | [135] |

| Grapevine Vst1 | Stress responsive pVst1 | Piceid | 3 to 7 for non-UV-irradiated fruit and 23 to 62 for UV-irradiated fruit | No influence on other phenolic compounds | [136] | |

| Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) | Grapevine Vst1 and Vst2 | Stress responsive pVst1 | Resveratrol | — | Resistance to Phytophthora infestans No resistance to Botrytis cinerea and Alternaria solani | [143] |

| Grapevine StSy | Constitutive pCaMV 35S | Resveratrol and piceid | 4 to 53 | Antioxidant primary metabolism and increase in total antioxidant activity | [144] | |

| Grapevine StSy | Constitutive pCaMV 35S | Resveratrol and piceid | 0.1 to 1.2 | Enhancement of natural antiradical properties | [145] | |

| Grapevine StSy | Constitutive pCaMV 35S | Resveratrol and piceid | 0.42 to 126 depending on the stage of ripening and fruit samples | Differences in rutin, naringenin, and chlorogenic acid contents | [146] | |

| Grapevine StSy | Fruit-specific promoter TomLoxB | Resveratrol and piceid | Increases in total antioxidant capability and ascorbic acid content | [147] | ||

| Rehmannia glutinosa Libosch. | Arachis hypogea AhRS3 | Constitutive pCaMV 35S | Resveratrol and piceid | 22 to 116 up to 650 with stress treatment | Antioxidant capabilities Resistance to Fusarium oxysporum | [142] |

| Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) | Parthenocissus henryanaSTS | Constitutive pCaMV 35S | Resveratrol | 56.4 | Effect on Hela cell morphology | [101] |

| Pea (Pisum. sativum L.) | Grapevine Vst1 | Stress responsive pVst1 | Occurrence of two resveratrol-glucoside compounds | 0.53 to 5.2 | — | [149] |

| White poplar (Populus alba L.) | Grapevine StSy | Constitutive pCaMV 35S | Piceid | 309 to 615 | No in vitro resistance to Melampsora pulcherrima | [137, 139] |

| Papaya (Carica papaya L.) | Grapevine Vst1 | Stress responsive pVst1 | Resveratrol glucoside | 54 | Resistance to Phytophthora palmivora | [138] |

| Oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) | Grapevine Vst1 | Tissue specific p-nap | Resveratrol glucoside | 361 to 616 | Food quality improvement: high piceid rate content and reduction of sinapate esters | [140] |

| Hop (Humulus lupulus L.) | Grapevine Vst1 | Constitutive pCaMV 35S | Piceid, unknown stilbene astringin, resveratrol | 490 to 560 | Higher amounts of flavonoids and acids | [150] |

In grapevine, genome sequencing has revealed a large array of STS genes, with 43 genes identified and 20 of these being shown to be expressed [151]. But to date, only a few STS genes from grapevine are used for the metabolic engineering of plants, being Vst1 and Stsy the most commonly genes chosen (Table 2). STS-encoding genes from other plants have also been used, notably the AhRS gene from Arachis hypogea [100, 131], the SbSTS1 gene from Sorghum bicolor [106, 148], and an STS-encoding gene from Parthenocissus henryana [101]. Chimeric genes or a combination of two STS encoding genes, based on Vst1 and Vst2, can increase significantly resveratrol production in the transformed lines [128, 152].

On a practical point of view, the modulation of gene expression is mainly controlled by the promoter chosen to drive the transgene. By now, a limited number of promoters (the constitutive promoter pCaMV35S, its own stress-responsive promoter pVst1, the fungus-inducible promoter pPR10.1 or the tissue specific promoter p-nap) have been used for the expression of STS-encoding genes upon plant transformation (Table 2 and references therein). As expected, the pCaMV35S promoter, which is the most commonly used to overexpress a transgene in plants [152], triggered strong and constitutive stilbene accumulation (Table 2). In this case, stilbene synthesis is higher than that observed with inducible promoters, but, as a consequence, causes a drastic depletion of the endogenous pools of precursors. In grapevine, the pVst1 promoter which is induced either by biotic factors (pathogens, elicitors) or abiotic stresses (wounding, UV light), allows high stilbene production without interfering with secondary biosynthetic pathways. Generally, it appears thus preferable to transform plants with a construct having a pathogen-inducible promoter in order to avoid depletion of other pathways.

Expression of the STS gene may be optimized by the utilization of enhancer elements [127, 130] and/or heterologous promoters [131–135, 140, 152] to improve STS transcription. Combination of the pVst1 promoter with the 35S enhancer element [127, 130] or use of a chimeric promoter resulting, for example, from a fusion between the alfalfa pPR10.1 promoter and the pVst1 promoter can lead to higher expression of the transgene without affecting promoter inducibility or specific expression patterns [127], or to an increased production of resveratrol upon fungal infection (reaching 5–100-fold the levels found in nontransgenic leaves [133]). Finally, tissue-specific promoters such as the p-nap seed-specific napin promoter can be used to induce stilbene production [140].

At this stage of the discussion, it appears important to underline that the choice of the promoter for STS gene expression should be performed depending on the expected results: when the enhancement of plant resistance against pathogens through resveratrol production is searched, thus one can recommend the choice of a strong constitutive promoter or a pathogen-inducible promoter (see above). As far as may concern this review, when the improvement of food products is sought through, for example the increase of the antioxidant activity of the transformed plants, a tissue-specific [140, 147] or inducible promoter would be a better option.

STS genes were transferred to plants by means of Agrobacterium spp. in tomato [143], grapevine [133], kiwifruits [132] or particle bombardment in barley and wheat [127–129]. However, as epigenetic modifications may occur and lead to expression variability, decreasing the ability of the transgenes for stilbene synthesis, the selection of plants with a single gene insertion will be more appropriate. As a consequence, the use of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, which leads to lower transgene insertion numbers, should preferentially be chosen [124].

5.2. Stilbene Production and Biological Benefits of Resveratrol Synthesis in STS Engineered Plants

Expression of STS genes resulted in resveratrol accumulation in transgenic lines. The obtained stilbene amounts are generally higher than those reached in engineered yeast, ranging from a few mg/kg fresh weight to hundreds of mg/kg fresh weight (see Table 2). Both free resveratrol and its glycosylated forms can be recovered in plant extracts [144]: piceid, a 3-O-β-D-resveratrol glucoside, occurred in different plant species transformed with STS genes (Table 2) [106, 132, 136, 139, 140, 142, 145, 146, 148, 150]. However, levels of accumulated stilbenes depend on the plant species (probably because of different endogenous pools of enzymes or precursors, as well as differences in secondary metabolism pathways), the promoter used (constitutive or inducible promoters), the ripening stage in case of transgenic fruits [136, 144] and the age of the organs [125, 132].

From a practical viewpoint, the ectopic production of resveratrol observed in transformed plants can lead to broad-spectrum resistance against fungi in transgenic plants, but disparate effects were observed (Table 2). Some works indeed reported transformations improving the resistance of rice to Pyricularia oryzae [126], tomato to Phytophthora infestans [143], barley and wheat to B. cinerea [127, 129], wheat to Oidium tuckeri [127, 129], alfalfa to Phoma medicaginis [131] and papaya to Phytophthora palmivora [138]. Conversely, in some others, no resistance was observed after transforming the plants with stilbene synthase genes. For example, transformation of white poplar (Populus alba) with STS, leading to the accumulation of piceid, does not confer any increased resistance to rust disease (Melaspora pulcherrima) [137, 139]. Similarly, no increased resistance against B. cinerea has been observed in STS transgenic kiwi plants [132].

With regard to the improvement of the nutritional value of agricultural crops and fruits, there are already several studies reporting an increase of the antioxidant activities in transgenic tomatoes and apples overexpressing STS-encoding genes [136, 144, 147]. In tomato, for example, resveratrol accumulation in transgenic fruit increased their global antioxidant activities, as well as their contents in other well-known antioxidants such as ascorbic acid and glutathione [144]. Antioxidant activity, as a consequence of resveratrol accumulation, was also shown to suffer a two-fold increase in transgenic tomato fruit versus controls [145]. Moreover, a correlation was found between resveratrol concentrations and antioxidant activities in ripe and unripe fruits [145]. More recently [147], tomato plants expressing a stilbene synthase gene (StSy) under the control of a fruit-specific promoter (promoter TomLoxB) were shown to accumulate resveratrol and piceid in the skin of the mature fruits, being the resveratrol content of the plants transformed with the specific promoter TomLoxB 20-fold lower than that of plants previously transformed with the constitutive pCaMV35S promoter [144]. However, both the total antioxidant capability and the ascorbic acid content were increased in the transformed fruits. These results explain the higher capability of transgenic fruits to counteract the proinflammatory effects of phorbol ester in monocyte–macrophages via the inhibition of induced cyclo-oxygenase-2 enzyme [147]. This last example constitutes a nice illustration of what can be expected from molecular engineering of resveratrol in plants in terms of improvement of the nutritional value of fruits or food products.

6. Conclusions

Increased demand for resveratrol for nutraceutical, cosmetic and possibly pharmaceutic uses makes its production from sustainable sourcing a necessity. In this context, the use of biotechnology through recombinant microorganisms and plants is particularly promising [5, 112, 118]. Interesting results can indeed arise from the potential of genetically modified microorganisms as an alternative mechanism for producing resveratrol, as this compound can be synthesized directly in recombinant yeast (the subject of the present review) but also in bacteria, such as Escherichia coli [112, 118]. Use of recombinant bacteria or yeast is of interest for the food industry, which could produce resveratrol in large quantities in biofermentators. Tailoring yeast can also receive direct applications in winemaking, as for example, fermentation engineering to produce resveratrol in wine (or to increase the wine resveratrol content) [119]. Otherwise, a transgenic yeast expressing a gene for a glycosyl hydrolase capable of liberating free resveratrol from its glucoside form has been reported as well to increase resveratrol amounts in wine [153] or the wine-related antioxidant content [114]. Beside the fact that disease resistance can be obtained following expression of STS-encoding genes, molecular engineering of plants with resveratrol may also lead to food products comprising edible legumes, cereals, or fruits, which can be ingested with their potential clinical benefits, by humans. Taken together, these results suggest the overall relevance of metabolic engineering of resveratrol.

References

- 1.Morales M, Ros Barcelo A, Pedreno MA. Plant stilbenes: recent advances in their chemistry and biology. Advances in Plant Physiology. 2000;3:39–70. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeandet P, Breuil AC, Adrian M, et al. HPLC analysis of grapevine phytoalexins coupling photodiode array detection and fluorometry. Analytical Chemistry. 1997;69:5172–5177. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeandet P, Douillet-Breuil AC, Bessis R, Debord S, Sbaghi M, Adrian M. Phytoalexins from the vitaceae: biosynthesis, phytoalexin gene expression in transgenic plants, antifungal activity, and metabolism. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2002;50(10):2731–2741. doi: 10.1021/jf011429s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chong J, Poutaraud A, Hugueney P. Metabolism and roles of stilbenes in plants. Plant Science. 2009;177(3):143–155. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeandet P, Delaunois B, Conreux A, et al. Biosynthesis, metabolism, molecular engineering, and biological functions of stilbene phytoalexins in plants. BioFactors. 2010;36(5):331–341. doi: 10.1002/biof.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takaoka MJ. Of the phenolic substances of white hellebore (Veratrum grandiflorum Loes. Fil.) Journal of the Faculty of Science Hokkaido Imperial University. 1940;3:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baur JA, Sinclair DA. Therapeutic potential of resveratrol: the in vivo evidence. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2006;5(6):493–506. doi: 10.1038/nrd2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King RE, Bomser JA, Min DB. Bioactivity of resveratrol. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2006;5(3):65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saiko P, Szakmary A, Jaeger W, Szekeres T. Resveratrol and its analogs: defense against cancer, coronary disease and neurodegenerative maladies or just a fad? Mutation Research. 2008;658(1-2):68–94. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pezzuto JM. The phenomenon of resveratrol: redefining the virtues of promiscuity. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2011;1215(1):123–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez J, Moreno JJ. Effect of resveratrol, a natural polyphenolic compound, on reactive oxygen species and prostaglandin production. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2000;59(7):865–870. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00380-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Losa GA. Resveratrol modulates apoptosis and oxidation in human blood mononuclear cells. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003;33(9):818–823. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2003.01219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jang M, Pezzuto JM. Cancer chemopreventive activity of resveratrol. Drugs under Experimental and Clinical Research. 1999;25(2-3):65–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai YJ, Fang JG, Ma LP, Yang L, Liu ZL. Inhibition of free radical-induced peroxidation of rat liver microsomes by resveratrol and its analogues. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2003;1637(1):31–38. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(02)00174-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leonard SS, Xia C, Jiang BH, et al. Resveratrol scavenges reactive oxygen species and effects radical-induced cellular responses. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2003;309(4):1017–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.08.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frankel EN, Waterhouse AL, Kinsella JE. Inhibition of human LDL oxidation by resveratrol. The Lancet. 1993;341(8852):1103–1104. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92472-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belguendouz L, Fremont L, Linard A. Resveratrol inhibits metal ion-dependent and independent peroxidation of porcine low-density lipoproteins. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1997;53(9):1347–1355. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(96)00820-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferroni F, Maccaglia A, Pietraforte D, Turco L, Minetti M. Phenolic antioxidants and the protection of low density lipoprotein from peroxynitrite-mediated oxidations at physiologic CO2. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2004;52(10):2866–2874. doi: 10.1021/jf034270n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olas B, Zbikowska HM, Wachowicz B, Krajewski T, Buczyński A, Magnuszewska A. Inhibitory effect of resveratrol on free radical generation in blood platelets. Acta Biochimica Polonica. 1999;46(4):961–966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmad A, Syed FA, Singh S, Hadi SM. Prooxidant activity of resveratrol in the presence of copper ions: mutagenicity in plasmid DNA. Toxicology Letters. 2005;159(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Athar M, Back JH, Kopelovich L, Bickers DR, Kim AL. Multiple molecular targets of resveratrol: anti-carcinogenic mechanisms. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2009;486(2):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Athar M, Back JH, Tang X, et al. Resveratrol: a review of preclinical studies for human cancer prevention. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2007;224(3):274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clément MV, Hirpara JL, Chawdhury SH, Pervaiz S. Chemopreventive agent resveratrol, a natural product derived from grapes, triggers CD95 signaling-dependent apoptosis in human tumor cells. Blood. 1998;92(3):996–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delmas D, Rébé C, Micheau O, et al. Redistribution of CD95, DR4 and DR5 in rafts accounts for the synergistic toxicity of resveratrol and death receptor ligands in colon carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2004;23(55):8979–8986. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Su JL, Lin MT, Hong CC, et al. Resveratrol induces FasL-related apotosis through Cdc42 activation of ASK1/JNK-dependent signaling pathway in human leukemia HL-60 cells. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:2005–2013. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dörrie J, Gerauer H, Wachter Y, Zunino SJ. Resveratrol induces extensive apoptosis by depolarizing mitochondrial membranes and activating caspase-9 in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Cancer Research. 2001;61(12):4731–4739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuwajerwala N, Cifuentes E, Gautam S, Menon M, Barrack ER, Veer Reddy GP. Resveratrol induces prostate cancer cell entry into S phase and inhibits DNA synthesis. Cancer Research. 2002;62(9):2488–2492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pozo-Guisado E, Alvarez-Barrientos A, Mulero-Navarro S, Santiago-Josefat B, Fernandez-Salguero PM. The antiproliferative activity of resveratrol results in apoptosis in MCF-7 but not in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells: cell-specific alteration of the cell cycle. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2002;64(9):1375–1386. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01296-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fulda S, Debatin KM. Sensitization for tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-induced apoptosis by the chemopreventive agent resveratrol. Cancer Research. 2004;64(1):337–346. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Estrov Z, Shishodia S, Faderl S, et al. Resveratrol blocks interleukin-1β-induced activation of the nuclear transcription factor NF-κB, inhibits proliferation, causes S-phase arrest, and induces apoptosis of acute myeloid leukemia cells. Blood. 2003;102(3):987–995. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsieh TC, Halicka D, Lu X, et al. Effects of resveratrol on the G0-G1 transition and cell cycle progression of mitogenically stimulated human lymphocytes. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2002;297(5):1311–1317. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsieh TC, Juan G, Darzynkiewicz Z, Wu JM. Resveratrol increases nitric oxide synthase, induces accumulation of p53 and p21WAF1/CIPI1, and suppresses cultured bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cell proliferation by perturbing progression through S and G2. Cancer Research. 1999;59(11):2596–2601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jang M, Cai L, Udeani GO, et al. Cancer chemopreventive activity of resveratrol, a natural product derived from grapes. Science. 1997;275(5297):218–220. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park JW, Choi YJ, Suh SI, et al. Bcl-2 overexpression attenuates resveratrol-induced apoptosis in U937 cells by inhibition of caspase-3 activity. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22(10):1633–1639. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.10.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou HB, Yan Y, Sun YN, Zhu JR. Resveratrol induces apoptosis in human esophageal carcinoma cells. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2003;9(3):408–411. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i3.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim YA, Lee WH, Choi TH, Rhee SH, Park KY, Choi YH. Involvement of p21WAF1/CIPI1, pRB, Bax and NF-kappaB in induction of growth arrest and apoptosis by resveratrol in human lung carcinoma A549 cells. International Journal of Oncology. 2003;23(4):1143–1149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahmad N, Adhami VM, Afaq F, Feyes DK, Mukhtar H. Resveratrol causes WAF-1/p21-mediated G1-phase arrest of cell cycle and induction of apoptosis in human epidermoid carcinoma A431 cells. Clinical Cancer Research. 2001;7(5):1466–1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kapadia GJ, Azuine MA, Tokuda H, et al. Chemopreventive effect of resveratrol, sesamol, sesame oil and sunflower oil in the Epstein-Barr virus early antigen activation assay and the mouse skin two-stage carcinogenesis. Pharmacological Research. 2002;45(6):499–505. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2002.0992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pervaiz S. Resveratrol- from the bottle to the bedside? Leukemia and Lymphoma. 2001;40(5-6):491–498. doi: 10.3109/10428190109097648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Afaq F, Adhami VM, Ahmad N. Prevention of short-term ultraviolet B radiation-mediated damages by resveratrol in SKH-1 hairless mice. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2003;186(1):28–37. doi: 10.1016/s0041-008x(02)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao X, Xu YX, Divine G, Janakiraman N, Chapman RA, Gautam SC. Disparate in vitro and in vivo antileukemic effects of resveratrol, a natural polyphenolic compound found in grapes. Journal of Nutrition. 2002;132(7):2076–2081. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.7.2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Potter GA, Patterson LH, Wanogho E, et al. The cancer preventative agent resveratrol is converted to the anticancer agent piceatannol by the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP1b1. British Journal of Cancer. 2002;86(5):774–778. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhat KPL, Lantvit D, Christov K, Mehta RG, Moon RC, Pezzuto JM. Estrogenic and antiestrogenic properties of resveratrol in mammary tumor models. Cancer Research. 2001;61(20):7456–7463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kimura Y, Okuda H. Effects of naturally occurring stilbene glucosides from medicinal plants and wine, on tumour growth and lung metastasis in Lewis lung carcinoma-bearing mice. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2000;52(10):1287–1295. doi: 10.1211/0022357001777270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kimura Y, Okuda H. Resveratrol isolated from Polygonum cuspidatum root prevents tumor growth and metastasis to lung and tumor-induced neovascularization in lewis lung carcinoma-bearing mice. Journal of Nutrition. 2001;131(6):1844–1849. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.6.1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carbo N, Costelli P, Baccino FM, Lopez-Soriano FJ, Argiles JM. Resveratrol, a natural product present in wine, decreases tumour growth in a rat tumour model. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1999;254:739–743. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kozuki Y, Miura Y, Yagasaki K. Resveratrol suppresses hepatoma cell invasion independently of its anti-proliferative action. Cancer Letters. 2001;167(2):151–156. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00476-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schneider Y, Duranton B, Gossé F, Schleiffer R, Seiler N, Raul F. Resveratrol inhibits intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates host-defense-related gene expression in an animal model of human familial adenomatous polyposis. Nutrition and Cancer. 2001;39(1):102–107. doi: 10.1207/S15327914nc391_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang SS, Tsai MC, Chih CL, Hung LM, Tsai SK. Resveratrol reduction of infarct size in Long-Evans rats subjected to focal cerebral ischemia. Life Sciences. 2001;69(9):1057–1065. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01195-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sinha K, Chaudhary G, Kumar Gupta Y. Protective effect of resveratrol against oxidative stress in middle cerebral artery occlusion model of stroke in rats. Life Sciences. 2002;71(6):655–665. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)01691-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu SN. Large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels: physiological role and pharmacology. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2003;10(8):649–661. doi: 10.2174/0929867033457863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karlsson J, Emgård M, Brundin P, Burkitt MJ. trans-Resveratrol protects embryonic mesencephalic cells from tert-butyl hydroperoxide: electron paramagnetic resonance spin trapping evidence for a radical scavenging mechanism. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2000;75(1):141–150. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kiziltepe U, Turan NND, Han U, Ulus AT, Akar F. Resveratrol, a red wine polyphenol, protects spinal cord from ischemia-reperfusion injury. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2004;40(1):138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nicolini G, Rigolio R, Scuteri A, et al. Effect of trans-resveratrol on signal transduction pathways involved in paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Neurochemistry International. 2003;42(5):419–429. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Virgili M, Contestabile A. Partial neuroprotection of in vivo excitotoxic brain damage by chronic administration of the red wine antioxidant agent, trans-resveratrol in rats. Neuroscience Letters. 2000;281(2-3):123–126. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00820-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gupta YK, Chaudhary G, Sinha K, Srivastava AK. Protective effect of resveratrol against intracortical FeCl3-induced model of posttraumatic seizures in rats. Methods and Findings in Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology. 2001;23(5):241–244. doi: 10.1358/mf.2001.23.5.662120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gupta YK, Chaudhary G, Srivastava AK. Protective effect of resveratrol against pentylenetetrazole-induced seizures and its modulation by an adenosinergic system. Pharmacology. 2002;65(3):170–174. doi: 10.1159/000058044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gentilli M, Mazoit JX, Bouaziz H, et al. Resveratrol decreases hyperalgesia induced by carrageenan in the rat hind paw. Life Sciences. 2001;68(11):1317–1321. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)01018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sharma M, Gupta YK. Chronic treatment with trans resveratrol prevents intracerebroventricular streptozotocin induced cognitive impairment and oxidative stress in rats. Life Sciences. 2002;71(21):2489–2498. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)02083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Doré S. Decreased activity of the antioxidant heme oxygenase enzyme: implications in ischemia and in Alzheimer’s disease. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2002;32(12):1276–1282. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00805-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anekonda TS. Resveratrol-a boon for treating Alzheimer’s disease? Brain Research Reviews. 2006;52(2):316–326. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hung LM, Su MJ, Chu WK, Chiao CW, Chan WF, Chen JK. The protective effect of resveratrols on ischaemia-reperfusion injuries of rat hearts is correlated with antioxidant efficacy. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2002;135(7):1627–1633. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hayek T, Fuhrman B, Vaya J, et al. Reduced progression of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice following consumption of red wine, or its polyphenols quercetin or catechin, is associated with reduced susceptibility of LDL to oxidation and aggregation. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 1997;17(11):2744–2752. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.11.2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vinson JA, Teufel K, Wu N. Red wine, dealcoholized red wine, and especially grape juice, inhibit atherosclerosis in a hamster model. Atherosclerosis. 2001;156(1):67–72. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00625-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zou J, Huang Y, Cao K, et al. Effect of resveratrol on intimal hyperplasia after endothelial denudation in an experimental rabbit model. Life Sciences. 2000;68(2):153–163. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00925-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mnjoyan ZH, Fujise K. Profound negative regulatory effects by resveratrol on vascular smooth muscle cells: a role of p53-p21WAF1/CIPI1 pathway. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2003;311(2):546–552. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang Z, Huang Y, Zou J, Cao K, Xu Y, Wu JM. Effects of red wine and wine polyphenol resveratrol on platelet aggregation in vivo and in vitro. International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2002;9(1):77–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schriever C, Pendland SL, Mahady GB. Red wine, resveratrol, Chlamydia pneumoniae and the French connection. Atherosclerosis. 2003;171(2):379–380. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2003.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mahady GB, Pendland SL. Resveratrol inhibits the growth of Helicobacter pyloriin vitro. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2000;95(7):p. 1849. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mahady GB, Pendland SL, Chadwick LR. Resveratrol and red wine extracts inhibit the growth of CagA+ strains of Helicobacter pylori in vitro. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2003;98(6):1440–1441. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07513.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chan MMY. Antimicrobial effect of resveratrol on dermatophytes and bacterial pathogens of the skin. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2002;63(2):99–104. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00886-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Docherty JJ, Fu MM, Tsai M. Resveratrol selectively inhibits Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2001;47(2):243–244. doi: 10.1093/jac/47.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Langcake P, Pryce RJ. The production of resveratrol by Vitis vinifera and other members of the Vitaceae as a response to infection or injury. Physiological Plant Pathology. 1976;9(1):77–86. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Langcake P. Disease resistance of Vitis spp. and the production of the stress metabolites resveratrol, ε-viniferin, α-viniferin and pterostilbene. Physiological Plant Pathology. 1981;18:213–226. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Adrian M, Jeandet P, Veneau J, Weston LA, Bessis R. Biological activity of resveratrol, a stilbenic compound from grapevines, against Botrytis cinerea, the causal agent for gray mold. Journal of Chemical Ecology. 1997;23(7):1689–1702. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Adrian M, Rajaei H, Jeandet P, Veneau J, Bessis R. Resveratrol oxidation in Botrytis cinerea conidia. Phytopathology. 1998;88(5):472–4776. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1998.88.5.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Adrian M, Jeandet P. Resveratrol as an antifungal agent. In: Aggarwal BB, Shishodia S, editors. Resveratrol in Health and Disease. Boca Raton, Fla, USA: CRC Press; 2006. pp. 475–497. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Alessandro M, Di Marco S, Osti F, Cesari A. Bioassays on the activity of resveratrol, pterostilbene and phosphorous acid towards fungi associated with esca of grapevine. Phytopathologia Mediterranea. 2000;39(3):357–365. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jung HJ, Hwang IA, Sung WS, et al. Fungicidal effect of resveratrol on human infectious fungi. Archives of Pharmacal Research. 2005;28(5):557–560. doi: 10.1007/BF02977758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Howitz KT, Bitterman KJ, Cohen HY, et al. Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan. Nature. 2003;425(6954):191–196. doi: 10.1038/nature01960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wood JG, Rogina B, Lavu S, et al. Sirtuin activators mimic caloric restriction and delay ageing in metazoans. Nature. 2004;430(7000):686–689. doi: 10.1038/nature02789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Barger JL, Kayo T, Vann JM, et al. A low dose of dietary resveratrol partially mimics caloric restriction and retards aging parameters in mice. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002264. Article ID e2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tyagi A, Gu M, Takahata T, et al. Resveratrol selectively induces DNA damage, independent of Smad 4 expression, in its efficacy against human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011;17:5402–5411. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Back JH, Rezvani HR, Zhu Y, et al. Cancer cell survival following DNA damage-mediated premature senescence is regulated by mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-dependent inhibition of sirtuin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286(21):19100–19108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.240598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Langcake P, Pryce RJ. The production of resveratrol and the viniferins by grapevines in response to ultraviolet irradiation. Phytochemistry. 1977;16(8):1193–1196. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Austin MB, Noel JP. The chalcone synthase superfamily of type III polyketide synthases. Natural Product Reports. 2003;20(1):79–110. doi: 10.1039/b100917f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yu O, Jez JM. Nature’s assembly line: biosynthesis of simple phenylpropanoids and polyketides. Plant Journal. 2008;54(4):750–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jeandet P, Bessis R, Sbaghi M, Meunier P. Production of the phytoalexin resveratrol by grapes as a response to Botrytis attack under natural conditions. Journal of Phytopathology. 1995;143:135–139. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Adrian M, Jeandet P, Bessis R, Joubert JM. Induction of phytoalexin (resveratrol) synthesis in grapevine leaves treated with aluminum chloride (AlCl3) Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1996;44(8):1979–1981. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Douillet-Breuil AC, Jeandet P, Adrian M, Bessis R. Changes in the phytoalexin content of various Vitis spp. in response to ultraviolet C elicitation. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1999;47(10):4456–4461. doi: 10.1021/jf9900478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Adrian M, Jeandet P, Douillet-Breuil AC, Tesson L, Bessis R. Stilbene content of mature Vitis vinifera berries in response to UV-C elicitation. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2000;48(12):6103–6105. doi: 10.1021/jf0009910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schubert R, Fischer R, Hain R, et al. An ozone-responsive region of the grapevine resveratrol synthase promoter differs from the basal pathogen-responsive sequence. Plant Molecular Biology. 1997;34(3):417–426. doi: 10.1023/a:1005830714852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Krisa S, Larronde F, Budzinski H, Decendit A, Deffieux G, Mérillon JM. Stilbene production by Vitis vinifera cell suspension cultures: methyl jasmonate induction and 13C biolabeling. Journal of Natural Products. 1999;62(12):1688–1690. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Aziz A, Poinssot B, Daire X, et al. Laminarin elicits defense responses in grapevine and induces protection against Botrytis cinerea and Plasmopara viticola. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2003;16(12):1118–1128. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.12.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Aziz A, Trotel-Aziz P, Dhuicq L, Jeandet P, Couderchet M, Vernet G. Chitosan oligomers and copper sulfate induce grapevine defense reactions and resistance to gray mold and downy mildew. Phytopathology. 2006;96(11):1188–1194. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-96-1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Verhagen BWM, Trotel-Aziz P, Couderchet M, Höfte M, Aziz A. Pseudomonas spp.-induced systemic resistance to Botrytis cinerea is associated with induction and priming of defence responses in grapevine. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2010;61(1):249–260. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Verhagen B, Trotel-Aziz P, Jeandet P, Baillieul F, Aziz A. Improved resistance against Botrytis cinerea by grapevine-associated bacteria that induce a prime oxidative burst and phytoalexin production. Phytopathology. 2011;101(7):768–777. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-09-10-0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Melchior F, Kindl H. Coordinate- and elicitor-dependent expression of stilbene synthase and phenylalanine ammonia-lyase genes in Vitis cv. Optima. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1991;288(2):552–557. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90234-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wiese W, Vornam B, Krause E, Kindl H. Structural organization and differential expression of three stilbene synthase genes located on a 13 kb grapevine DNA fragment. Plant Molecular Biology. 1994;26(2):667–677. doi: 10.1007/BF00013752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hain R, Bieseler B, Kindl H, Schröder G, Stöcker R. Expression of a stilbene synthase gene in Nicotiana tabacum results in synthesis of the phytoalexin resveratrol. Plant Molecular Biology. 1990;15(2):325–335. doi: 10.1007/BF00036918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Liu S, Hu Y, Wang X, Zhong J, Lin Z. High content of resveratrol in lettuce transformed with a stilbene synthase gene of Parthenocissus henryana. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2006;54(21):8082–8085. doi: 10.1021/jf061462k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Preisig-Müller R, Schwekendiek A, Brehm I, Reif HJ, Kindl H. Characterization of a pine multigene family containing elicitor-responsive stilbene synthase genes. Plant Molecular Biology. 1999;39(2):221–229. doi: 10.1023/a:1006163030646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kodan A, Kuroda H, Sakai F. Simultaneous expression of stilbene synthase genes in Japanese red pine (Pinus densiflora) seedlings. Journal of Wood Science. 2001;47(1):58–62. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kodan A, Kuroda H, Sakai F. A stilbene synthase from Japanese red pine (Pinus densiflora): implications for phytoalexin accumulation and down-regulation of flavonoid biosynthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(5):3335–3339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042698899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Goodwin PH, Hsiang T, Erickson L. A comparison of stilbene and chalcone synthases including a new stilbene synthase gene from Vitis riparia cv. Gloire de Montpellier. Plant Science. 2000;151(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yu CKY, Springob K, Schmidt J, et al. A stilbene synthase gene (SbSTS1) is involved in host and nonhost defense responses in sorghum. Plant Physiology. 2005;138(1):393–401. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.059337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pretorius IS. Tailoring wine yeast for the new millennium: novel approaches to the ancient art of winemaking. Yeast. 2000;16:675–729. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(20000615)16:8<675::AID-YEA585>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chemler JA, Koffas MA. Metabolic engineering for plant natural product biosynthesis in microbes. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2008;19(6):597–605. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wang Y, Chen S, Yu O. Metabolic engineering of flavonoids in plants and microorganisms. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2011;91:949–956. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3449-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Huang LL, Xue Z, Zhu QQ. Method for the production of resveratrol in a recombinant oleaginous microorganism. World Patent WO 2006125000 A2, 2006.

- 111.Katz M, Förster J, David H, et al. Metabolically engineered cells for the production of resveratrol or an oligomeric or glycosidically-bound derivative thereof. US Patent US 2008/0286844A1, 2008.

- 112.Donnez D, Jeandet P, Clément C, Courot E. Bioproduction of resveratrol and stilbene derivatives by plant cells and microorganisms. Trends in Biotechnology. 2009;27(12):706–713. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Trantas E, Panopoulos N, Ververidis F. Metabolic engineering of the complete pathway leading to heterologous biosynthesis of various flavonoids and stilbenoids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metabolic Engineering. 2009;11(6):355–366. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Becker JVW, Armstrong GO, Van Der Merwe MJ, Lambrechts MG, Vivier MA, Pretorius IS. Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for the synthesis of the wine-related antioxidant resveratrol. FEMS Yeast Research. 2003;4(1):79–85. doi: 10.1016/S1567-1356(03)00157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Beekwilder J, Wolswinkel R, Jonker H, Hall R, De Rie Vos CH, Bovy A. Production of resveratrol in recombinant microorganisms. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2006;72(8):5670–5672. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00609-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zhang Y, Li SZ, Li J, et al. Using unnatural protein fusions to engineer resveratrol biosynthesis in yeast and mammalian cells. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128(40):13030–13031. doi: 10.1021/ja0622094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sydor T, Schaffer S, Boles E. Considerable increase in resveratrol production by recombinant industrial yeast strains with use of rich medium. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2010;76(10):3361–3363. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02796-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wang Y, Chen H, Yu O. Metabolic engineering of resveratrol and other longevity boosting compounds. BioFactors. 2010;36(5):394–400. doi: 10.1002/biof.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wang Y, Halls C, Zhang J, Matsuno M, Zhang Y, Yu O. Stepwise increase of resveratrol biosynthesis in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae by metabolic engineering. Metabolic Engineering. 2011;13:455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wang Y, Yu O. Synthetic scaffolds increased resveratrol biosynthesis in engineered yeast cells. Journal of Biotechnology. 2012;157:258–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Watts KT, Lee PC, Schmidt-Dannert C. Biosynthesis of plant-specific stilbene polyketides in metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. BMC Biotechnology. 2006;6, article 22 doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-6-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Katsuyama Y, Funa N, Miyahisa I, Horinouchi S. Synthesis of unnatural flavonoids and stilbenes by exploiting the plant biosynthetic pathway in Escherichia coli. Chemistry and Biology. 2007;14(6):613–621. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Halls C, Yu O. Potential for metabolic engineering of resveratrol biosynthesis. Trends in Biotechnology. 2008;26(2):77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Delaunois B, Cordelier S, Conreux A, Clément C, Jeandet P. Molecular engineering of resveratrol in plants. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2009;7(1):2–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2008.00377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Hain R, Reif HJ, Krause E, et al. Disease resistance results from foreign phytoalexin expression in a novel plant. Nature. 1993;361(6408):153–156. doi: 10.1038/361153a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Stark-Lorenzen P, Nelke B, Hänßler G, Mühlbach HP, Thomzik JE. Transfer of a grapevine stilbene synthase gene to rice (Oryza sativa L.) Plant Cell Reports. 1997;16(10):668–673. doi: 10.1007/s002990050299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Leckband G, Lörz H. Transformation and expression of a stilbene synthase gene of Vitis vinifera L. in barley and wheat for increased fungal resistance. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1998;96(8):1004–1012. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Fettig S, Hess D. Expression of a chimeric stilbene synthase gene in transgenic wheat lines. Transgenic Research. 1999;8(3):179–189. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Liang H, Zheng J, Duan X, et al. A transgenic wheat with a stilbene synthase gene resistant to powdery mildew obtained by biolistic method. Chinese Science Bulletin. 2000;45(7):634–638. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Serazetdinova L, Oldach KH, Lörz H. Expression of transgenic stilbene synthases in wheat causes the accumulation of unknown stilbene derivatives with antifungal activity. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2005;162(9):985–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hipskind JD, Paiva NL. Constitutive accumulation of a resveratrol-glucoside in transgenic alfalfa increases resistance to Phoma medicaginis. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2000;13(5):551–562. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.5.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kobayashi S, Ding CK, Nakamura Y, Nakajima I, Matsumoto R. Kiwifruits (Actinidia deliciosa) transformed with a Vitis stilbene synthase gene produce piceid (resveratrol-glucoside) Plant Cell Reports. 2000;19(9):904–910. doi: 10.1007/s002990000203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Coutos-Thévenot P, Poinssot B, Bonomelli A, et al. In vitro tolerance to Botrytis cinerea of grapevine 41B rootstock in transgenic plants expressing the stilbene synthase Vst 1 gene under the control of a pathogen-inducible PR 10 promoter. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2001;52(358):901–910. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/52.358.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Fan C, Pu N, Wang X, et al. Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) with a novel stilbene synthase gene from Chinese wild Vitis pseudoreticulata. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture. 2008;92(2):197–206. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Szankowski I, Briviba K, Fleschhut J, Schönherr J, Jacobsen HJ, Kiesecker H. Transformation of apple (Malus domestica Borkh.) with the stilbene synthase gene from grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) and a PGIP gene from kiwi (Actinidia deliciosa) Plant Cell Reports. 2003;22(2):141–149. doi: 10.1007/s00299-003-0668-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Rühmann S, Treutter D, Fritsche S, Briviba K, Szankowski I. Piceid (resveratrol glucoside) synthesis in stilbene synthase transgenic apple fruit. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2006;54(13):4633–4640. doi: 10.1021/jf060249l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Seppänen SK, Syrjälä L, Von Weissenberg K, Teeri TH, Paajanen L, Pappinen A. Antifungal activity of stilbenes in in vitro bioassays and in transgenic Populus expressing a gene encoding pinosylvin synthase. Plant Cell Reports. 2004;22(8):584–593. doi: 10.1007/s00299-003-0728-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Zhu YJ, Agbayani R, Jazckson MC, Tang CS, Moore PH. Expression of the grapevine stilbene synthase gene VST 1 in papaya provides increased resistance against diseaes caused by Phytophthora palmivora. Planta. 2004;12:807–812. doi: 10.1007/s00425-004-1343-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Giorcelli A, Sparvoli F, Mattivi F, et al. Expression of the stilbene synthase (StSy) gene from grapevine in transgenic white poplar results in high accumulation of the antioxidant resveratrol glucosides. Transgenic Research. 2004;13(3):203–214. doi: 10.1023/b:trag.0000034658.64990.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Hüsken A, Baumert A, Milkowski C, Becker HC, Strack D, Möllers C. Resveratrol glucoside (Piceid) synthesis in seeds of transgenic oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2005;111(8):1553–1562. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-0085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Vishnevetsky J, Flaishman M, Cohen Y, et al. Transgenic disease resistant banana. World Patent, WO2005/047515, 2005.

- 142.Lim JD, Yun SJ, Chung IM, Yu CY. Resveratrol synthase transgene expression and accumulation of resveratrol glycoside in Rehmannia glutinosa. Molecular Breeding. 2005;16(3):219–233. [Google Scholar]

- 143.Thomzik JE, Stenzel K, Stöcker R, Schreier PH, Hain R, Stahl DJ. Synthesis of a grapevine phytoalexin in transgenic tomatoes (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) conditions resistance against Phytophthora infestans. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology. 1997;51(4):265–278. [Google Scholar]

- 144.Giovinazzo G, D’Amico L, Paradiso A, Bollini R, Sparvoli F, DeGara L. Antioxidant metabolite profiles in tomato fruit constitutively expressing the grapevine stilbene synthase gene. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2005;3(1):57–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2004.00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Morelli R, Das S, Bertelli A, et al. The introduction of the stilbene synthase gene enhances the natural antiradical activity of Lycopersicon esculentum mill. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2006;282(1-2):65–73. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-1260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Nicoletti I, De Rossi A, Giovinazzo G, Corradini D. Identification and quantification of stilbenes in fruits of transgenic tomato plants (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) by reversed phase HPLC with photodiode array and mass spectrometry detection. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2007;55(9):3304–3311. doi: 10.1021/jf063175m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.D’Introno A, Paradiso A, Scoditti E, et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of tomato fruits synthesizing different amounts of stilbenes. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2009;7(5):422–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2009.00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Yu CKY, Lam CNW, Springob K, Schmidt J, Chu IK, Lo C. Constitutive accumulation of cis-piceid in transgenic Arabidopsis overexpressing a sorghum stilbene synthase gene. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2006;47(7):1017–1021. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcj061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Richter A, Jacobsen HJ, De Kathen A, et al. Transgenic peas (Pisum sativum) expressing polygalacturonase inhibiting protein from raspberry (Rubus idaeus) and stilbene synthase from grape (Vitis vinifera) Plant Cell Reports. 2006;25(11):1166–1173. doi: 10.1007/s00299-006-0172-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Schwekendiek A, Spring O, Heyerick A, et al. Constitutive expression of a grapevine stilbene synthase gene in transgenic hop (Humulus lupulus L.) yields resveratrol and its derivatives in substantial quantities. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2007;55(17):7002–7009. doi: 10.1021/jf070509e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Jaillon O, Aury JM, Noel B, et al. The grapevine genome sequence suggests ancestral hexaploidization in major angiosperm phyla. Nature. 2007;449(7161):463–467. doi: 10.1038/nature06148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Fischer R, Budde I, Hain R. Stilbene synthase gene expression causes changes in flower colour and male sterility in tobacco. Plant Journal. 1997;11(3):489–498. [Google Scholar]

- 153.Gonzalez-Candelas L, Gil JV, Lamuela-Raventos RM, Ramon D. The use of transgenic yeasts expressing a gene encoding a glycosyl-hydrolase as a tool to increase resveratrol content in wine. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2000;59:179–183. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(00)00354-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]