Abstract

Skinner's definition of verbal behavior, with its brief and refined versions, has recently become a point of controversy among behavior analysts. Some of the arguments presented in this controversy might be based on a misreading of Skinner's (1957a) writings. An examination of Skinner's correspondence with editors of scientific journals shows his sophisticated mastery of English and his knowledge of contemporary approaches of linguistics, and might help to settle the meaning of the passages involved in the controversy. A more precise definition of verbal behavior, deduced from Skinner's distinction between verbal and nonverbal operants, is suggested, and a possible reason why Skinner did not define verbal behavior in the terms proposed by this alternative definition is discussed. The alternative definition is more compatible with a functional approach to behavior and highlights what is specific to verbal behavior by pointing to the conventions of the verbal community. Some possible consequences of adopting this alternative definition are described.

Keywords: B. F. Skinner, verbal behavior, verbal community, linguistics

Only words were not punished with

the natural order of things.

Words continue with their unlimit.

Manoel de Barros (2004, p. 77)1

A writer, a linguist, and a behavior analyst agreed to meet inside B. F. Skinner's skin. The result of this encounter materialized in 1957, as Verbal Behavior, an approach to speech whose most important theoretical and applied consequences are yet to come.

This paper will look to that seminal work and other sources to examine Skinner's definition of verbal behavior. It will also look at the most prevalent interpretation of his definition in the field of behavior analysis. In addition, it presents a heretofore unpublished correspondence between B. F. Skinner and journal editors in which Skinner discusses in detail some aspects of grammar. Some elements of this discussion will be used to suggest an alternative understanding of Skinner's definition of verbal behavior. This paper also suggests a rewording of Skinner's definition that incorporates in the body of the definition the criterion by which Skinner distinguished verbal from nonverbal behavior.

SKINNER'S DEFINITION OF VERBAL BEHAVIOR

In Verbal Behavior, Skinner offers a preliminary definition of the subject in Chapter 1 as “behavior reinforced through the mediation of other persons” (p. 2). He then refines it in Chapter 8 as “behavior reinforced through the mediation of other persons [who] must be responding in ways which have been conditioned precisely in order to reinforce the behavior of the speaker” (p. 225). The second part of the definition “[who] must be responding in ways which have been conditioned precisely in order to reinforce the behavior of the speaker” is a restriction on the first part, and its aim is to circumscribe verbal behavior as a particular kind of social behavior. The restriction, however, is not stated clearly enough: Which ways of responding are these to which the listener has been conditioned? And why and how does this mediation affect the behavior of the speaker in such an important manner that it requires an analysis separate from the rest of operant behavior?

Answers to these questions are found in several statements throughout Verbal Behavior. For example, the listener is conditioned to respond in ways that reinforce a speaker's behavior presenting the patterns found in “the ‘language’ … that is, … the reinforcing practices of the verbal community” (p. 36), and in “the ‘languages’ studied by the linguist” (p. 461; see also p. 28). The relation between verbal behavior and language, the practices of a verbal community, is fully stated here:

Verbal behavior is shaped and sustained by a verbal environment— by people who respond to behavior in certain ways because of the practices of the group of which they are members. These practices and the resulting interaction of speaker and listener yield the phenomena which are considered here under the rubric of verbal behavior. (Skinner, 1957a, p. 226)

These and other clarifying statements, addressed below, are scattered throughout different sections of Verbal Behavior. Moreover, an integrated definition of verbal behavior is offered in Upon Further Reflection (Skinner, 1987): “Verbal behavior is behavior that is reinforced through the mediation of other people, but only when the other people are behaving in ways that have been shaped and maintained by an evolved verbal environment, or language” (p. 90).

I suggest that in defining verbal behavior, Skinner was deliberately avoiding the use of the word language. Sometimes, as in two of the quotations above, he even puts the word language in quotation marks. We can guess why he did so. Although not always, in general he was very critical of linguistics, and wanted to present his explanation of verbal behavior as an alternative that would be “appropriate to all special fields” (1957a, p. 4). Interestingly, part of his criticism of linguistics and grammar probably resulted from his extensive reading of linguists who warned against the dangers of using the concept of language, unless one is truly aware of its nature as an abstraction, taken from the concreteness of speech. This conception of language as an abstraction was commonplace in 19th-century linguistics.

Two of these linguists, Max Müller (1823–1900) and Philipp Wegener (1848–1916), although not mentioned in Verbal Behavior, are mentioned in Skinner's William James Lectures,2 given in 1947 at Harvard University. There, Skinner (1948, p. 151) refers to Müller's famous and influential (Alter, 2005, pp. 63–65, 68–70) Lectures on the Science of Language (1861/1884) where we can read:

To speak of language as a thing by itself, as living a life of its own, as growing to maturity, producing offspring, and dying away, is sheer mythology; and though we cannot help using metaphorical expressions, we should always be on our guard … against being carried away by the very words which we are using. (p. 51) Language has no independent substantial existence. Language exists in man, it lives in being spoken, it dies with each word that is pronounced, and is no longer heard. (p. 58)

In the William James Lectures (p. 108), Skinner refers to Wegener, an author who had long been forgotten, but is now being rediscovered in the important subfield of linguistic pragmatics (Koerner, 1991, pp. vi–vii*; Nerlich & Clarke, 1996, p. 177). Wegener's general understanding of speech (Nerlich & Clarke, 1996, pp. 177–183) shares some important characteristics with Skinner's, and he seems to have been a significant source for Skinner's conception of the autoclitic (Passos, 2010). According to Wegener, “Language is not a being or an organism possessing spatial autonomy. … It is a collective name, indeed an abstraction, for certain muscular movements of man which are connected with a definite sense for many persons of a social group” (1885/1971, p. 121). Similar statements by leading linguists such as Hermann Paul (1846–1921; quoted in Jespersen, 1922, pp. 94–95) and Jespersen (1860–1943) (1922, p. 7) were also known to Skinner (Matos & Passos, 2010).

Whether or not he was avoiding referring to language, Skinner found a way of making clear that mediation by others is not enough to characterize verbal behavior by posing the restriction that the mediator must be “behaving in ways that have been shaped and maintained by an evolved verbal environment” (Skinner, 1987, p. 90). However, the restriction is still vague because it does not state clearly the ways in which the mediator is behaving, and the mediation of reinforcement by others became more conspicuous than the mediator's special conditioning in the conception of verbal behavior generally held by students in the field. This is stressed by Peterson in his fine investigation of the effect of shaping on Skinner's understanding of the power of reinforcement through the social environment:

Reinforcement by other people became definitive of verbal behavior. “Verbal behavior always involves social reinforcement and derives its characteristic properties from this fact” (Skinner, 1953, p. 299). In Verbal Behavior, Skinner defined verbal behavior generically as “behavior shaped and maintained by mediated consequences” (p. 2). … By mediated consequences, of course, he meant consequences controlled by another person. … The social mediation of the reinforcement process became the primary defining factor whereas all other aspects became secondary. (Peterson, 2004, p. 326)

Other scholars made the same point:

Many (most?) of our behavior analytic colleagues consider the little, nonverbal autistic kid's self-injury behavior and aggression as an attempt to communicate to the trainer that the training task is too difficult, or he wants some attention, which, of course, is the sort of thinking that leads to facilitated communication. And that's the sort of risk created by Skinner's definition of verbal behavior as behavior reinforced by someone else; from my view, it is simplistic; all behavior analysts lock into that simplistic definition, without attending to his more sophisticated later qualifications or supplements. (Malott, in Michael & Malott, 2003, p. 116)

Skinner wrote that verbal behavior was sufficiently different from other behavior to warrant special treatment. Its uniqueness lay in the role played by the mediation of others in its generation, maintenance, and control (Skinner, 1957, p. 2). (McPherson, Bonem, Green, & Osborne, 1984, p. 157)

CRITICISMS OF SKINNER'S DEFINITION OF VERBAL BEHAVIOR

Both the incomplete unrefined definition and the unclear refined one have misguided behavior analysts who then sometimes addressed undeserved criticisms of Skinner's approach to verbal behavior. This is the case of the criticisms by Hayes, Blackledge, and Barnes-Holmes (2001) that Skinner's definition of verbal behavior (a) is based on the history of reinforcement of another organism (the listener) instead of being based on the history of reinforcement of the speaker, and (b) is too broad and fails to distinguish between the behavior of animals and humans.

The first criticism is occasioned in part by the lack of specification in Skinner's definition of the ways in which the mediator is behaving and how these ways shape the speaker's behavior. But the ways in which the behavior of the mediator shapes and maintains the speaker's verbal behavior is made clear from the very beginning of Verbal Behavior in Skinner's discussion of the distinction between verbal and nonverbal behavior (pp. 1–2), the analysis of the listener's behavior (pp. 33–34), and also in subsequent chapters about the verbal operants. The history of reinforcement of the mediator builds the behavioral repertoire by which he or she becomes able to reinforce the speaker's behavior which represents the patterns found in the practices of the community. Therefore the history of reinforcement of the mediator explains, first of all, the listener's own behavior, not the speaker's. It also shows how the behavior of the listener is able to select the properties of the behavior of the speaker that mirror the patterns found in the conventions of the verbal community. The speaker's behavior then is explained, as it should be, by his or her own current circumstances and past environments, which include the reinforcements provided by the mediator.

This first criticism is also occasioned by a particular reading of the following footnote in Verbal Behavior that might not accurately reflect what Skinner meant, as I discuss below. This particular reading also gives rise to the second criticism, namely that Skinner's definition of verbal behavior is too broad and fails to distinguish between the behavior of animals and humans:

Our definition of verbal behavior, incidentally, includes the behavior of experimental animals where reinforcements are supplied by an experimenter or by an apparatus designed to establish contingencies which resemble those maintained by the normal listener. The animal and the experimenter comprise a small but genuine verbal community. (p. 108)

This note has been interpreted, not just by Hayes et al. (2001) but by several others in the field of behavior analysis (e.g., see Leigland, 1997; Michael & Malott, 2003; Normand, 2009; Palmer, 2008), as stating that all animal behavior in operant learning experiments is verbal because the reinforcement is directly or indirectly delivered by the experimenter, who was trained to do so (for a different understanding of Skinner's stand on this issue, see Osborne, 2003; Passos, 2007; and Vargas in Arntzen, 2010). As we will explore in the next section, it is possible that this is not what Skinner meant by his footnote, and the fact that so many scholars interpreted it in a way arguably not intended by Skinner might be partially explained by the point made by Malott and Peterson discussed above, that is, that mediation by others became the most conspicuous feature in the definition of verbal behavior.

SKINNER'S CORRESPONDENCE WITH EDITORS

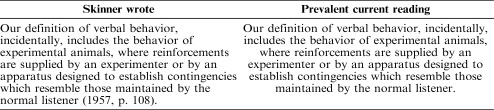

My contention is that Skinner's note was misread. Compare the two passages in Table 1 and note that they differ with respect to one comma. Even if tiny, the different effects of these sentences could be significant. As Skinner actually wrote it, without a comma, the phrase “where reinforcements are supplied by an experimenter or by an apparatus designed to establish contingencies which resemble those maintained by the normal listener” is restrictive. The phrase does not refer to all experiments with animals, just the ones to which the restriction applies, that is, to experiments with animals where the contingencies resemble those maintained by the normal listener. On the contrary, as this phrase has been interpreted by several behavior analysts, it would be nonrestrictive but then it should be set off by commas, because nonrestrictive clauses are set off by commas, and restrictive clauses are not (Kolln, 1982, pp. 183–195; Oshima & Hogue, 1991, pp. 208–228). As we will see next, Skinner, the writer, was very well aware of the difference between restrictive and nonrestrictive clauses and the way this difference is indicated in writing. If he did not set off the phrase by commas it was because he meant it as restrictive.

Table 1.

Comparison of Skinner's Writing and a Slightly Different Text

Having aimed to be a writer before entering the field of psychology (Skinner, 1976, pp. 262–283), Skinner had extensive training in English and other languages (Bjork, 1997, pp. 23, 31–48, 77; Skinner, 1983, p. 171) and remained a voracious reader of literature for his entire life (Coleman, 1985; Malone, 1999; Skinner, 1959, 1967). Two letters sent by Skinner to the editors of the journals Scientific Monthly, in 1954, and Science, in 1957, the year Verbal Behavior was published, show what a meticulous and elegant writer he was. In both of them, he complains vigorously about the editors having substituted that for which in his articles. His 1954 letter to the editor of Scientific Monthly is probably related to the editing of A Critique of Psychoanalytic Concepts and Theories (Skinner, 1954a/1999), published in 1954 in that journal. Skinner complains about a change made in “all the qualifying relative pronouns in my article from ‘whiches’ to ‘thats.’” He affirms that the grammarians have been prescribing this substitution for centuries, but he does not “subscribe to this bit of authoritarian dictation” (Skinner, 1954b).3

In the ensuing discussion, the reader will find “defining clause” as a synonym of “restrictive clause” and “nondefining clause” as a synonym of “nonrestrictive clause” (Burchfield & Fowler, 1996, p. 774). Normative grammarians such as Fowler prescribe the use of that as a relative pronoun to introduce a defining (restrictive) clause and of which to introduce a nondefining (nonrestrictive) clause:

The two kinds of relative clause, to one of which that & to the other of which which is appropriate, are the defining & the non-defining; & if writers would agree to regard that as the defining relative pronoun, & which as the non-defining, there would be much gain both in lucidity & in ease. (Fowler, 1926/2009, p. 635)

In the 1957 letter to the editors of Science, Skinner offers five different grammatical reasons why he disagrees with their editorial practice of substituting that for which. The fourth reason mentions Fowler's suggestion of using that to introduce defining (restrictive) relative clauses and which to introduce nondefining (nonrestrictive) relative clauses. Skinner disagrees with this suggestion on the basis that it is unnecessary to use that or which to mark the distinction between defining (restrictive) and nondefining (nonrestrictive) clauses, because this distinction is indicated in writing by commas (and in speech by pausing and vocal inflection):

Fowler's Modern English Usage is probably responsible for the current belief that there is logical elegance in using that as a defining restricting pronoun and which as a non-defining restricting. The distinction between the two cases is carried in speech by pausing and inflection, and in writing by commas. It has never been consistently carried by that vs. which (Skinner, 1957b).4

The letters reveal Skinner's strong command of his native language. It also shows an author so comfortable and confident about his writing that he is able to challenge Fowler, considered by many as the ultimate arbiter of correct usage. Fowler was the author of Modern English Usage, a prescriptive (also called normative, Crystal, 1980, p. 243) grammar that became the “go-to” reference work on English usage since its first appearance in 1926 (Crystal, 2009b). A prescriptive grammar5 is

a manual that focuses on constructions where usage is divided, and lays down rules governing the socially correct use of language. … These grammars were a formative influence on language attitudes in Europe and America during the 18th and 19th centuries. Their influence lives on in the handbooks of usage widely found today, such as A Dictionary of Modern English Usage (1926) by Henry Watson Fowler (1858–1933). (Crystal, 1997, p. 88)

According to Crystal (2009a), Fowler's perspective is inconsistent, because it oscillates between the prescriptive and the descriptive. Two of the developments in the study of language introduced by linguistics are a descriptive approach and the abandonment of the traditional prescriptive grammar, the latter being still prevalent in our schools and when laypersons talk about language. According to Beal (as quoted in Tieken-Boon, 2008), these prescriptive grammars “left us with a legacy of ‘linguistic insecurity’” (p. 9), which explains their popularity. Skinner's correspondence with the editors of Science shows that he, for one, did not feel this linguistic insecurity.6

AN ALTERNATIVE INTERPRETATION OF SKINNER'S FOOTNOTE

The correspondence described in the previous section shows that Skinner was aware of the use of a comma to introduce nonrestrictive relative clauses. The note in Verbal Behavior that we are examining contains a relative clause that starts with the relative adverb where and is not introduced by a comma. Relative clauses introduced by where can also be restrictive or nonrestrictive, and the punctuation convention discussed above applies as well to their case (Kolln, 1982; Oshima & Hogue, 1991). The point of this discussion is that Skinner intended the part of the sentence italicized to be a restriction on the first part of the sentence:

Our definition of verbal behavior, incidentally, includes the behavior of experimental animals where reinforcements are supplied by an experimenter or by an apparatus designed to establish contingencies which resemble those maintained by the normal listener. (p. 108, italics added)

We should, thus, only consider the behavior of experimental animals to be verbal in certain experiments, namely, the ones in which the contingencies are like the ones maintained by a listener. This interpretation is strengthened by Skinner's explicit statement in The Behavior of Organisms (1938/1991) that pressing the lever by the rat in the experimental situation is not like verbal behavior, given that it acts on the environment. On explaining why he did not choose to study in his experiments responses like flexing a leg instead of pressing the lever, he says,

It is only in verbal behavior that such non-mechanically effective responses [flexing a leg or flicking the tail] are reinforced (i.e., when they become gestures). In general, a response must act upon the environment to produce its own reinforcement. Although the connection between the movement of the lever and reinforcement is in one sense artificial, it closely parallels the typical discriminated operant in the normal behavior of the rat. (Skinner, 1938/1991, p. 50)

It is likely that Skinner was thinking about what occurs in shaping by hand when he wrote the restrictive expression in the footnote in Verbal Behavior. In 1943, Skinner, with Keller Breland and Norman Gutmann, apparently for the first time (Peterson, 2004), shaped behavior by hand. They wanted to teach a pigeon to bowl and decided to do it by reinforcing successive approximations because it would take a long time for a first response of swiping the ball with a movement of the beak to appear for it to be reinforced. They reinforced the first response that had a slight resemblance to the desired final response, proceeded by selecting responses that were more and more similar to the desired one, and were very surprised by how fast they conditioned the final response. Later, Skinner contrasted this shaping with one, not by hand, described in The Behavior of Organisms in which

the behavior was set up through successive approximations, but every stage was reached by constructing mechanical and electrical systems operated by the rat. In the experiment on bowling, however, we held the reinforcing switch in our hand and could reinforce any given form of behavior without constructing a mechanical or electrical system to report its occurrence. The mechanical connection between behavior and reinforcement was greatly attenuated. (Skinner, 1958/1999, p. 167)

Skinner attributed the speed in the conditioning of bowling to the combination of two factors that enhanced the effect of this shaping by hand: the use of a conditioned reinforcer (the sound of the food magazine) and “the free selection of topography resulting from hand reinforcement” (Skinner, 1958/1999, p. 167), where there is no mechanical connection between behavior and reinforcement. Likewise, the topographies of verbal operants are selected according to the conventions of the verbal community by the reinforcing action of the listener, not by any mechanical connection with the environment.

In Verbal Behavior (pp. 29–30), while discussing how parents establish a verbal repertoire in a child, Skinner noted that they do not need to wait for a first appearance of the complex forms that make an adult verbal repertoire; instead they can use a procedure (successive approximations) such as the one that could be used to teach “a pigeon to pace the floor of its cage in the pattern of a figure-8” (p. 29), a form of response that (a) is very unlikely to be emitted previously to any conditioning in order to be reinforced; and (b) has no mechanical effects on the environment, but has an effect on the experimenter. Skinner's description of the procedure to teach the pigeon to pace in the pattern of a figure eight is very similar to the description of the episode of shaping by hand described above.

The free selection of topography allowed by the lack of mechanical connections with the environment explains the unusual forms (e.g., the ones implied in bowling and pacing in the pattern of a figure eight) that can be taught to the pigeon, as well as the complex forms that make up the adult repertoire of verbal behavior. In A Psychological Analysis of Verbal Behavior,7 Skinner considers great diversity of form as one of the characteristics that result from the fact that verbal behavior “does not act mechanically upon the environment”:

Great diversity of form. It is possible to develop hundreds of thousands of different forms of response with the same effector without trying to find hundreds of thousands of objects which will move in different ways as a result of these complex patterns. In sports movements are relatively limited—for example, the things you can do with a tennis racquet. Only a few movements are selected by the mechanical action on a ball. (Skinner, 1947, p. 57)

VERBAL BEHAVIOR AND THE CONVENTIONS OF THE VERBAL COMMUNITY

A definition of behavior should specify its functional relation with the environment. In the case of the operant, it should specify the relation between consequences and the properties of responses that they select, not the physical agent that presents the consequences. Several properties can be selected, such as topography, duration, force, and so on (Catania, 1998, p. 120; Skinner, 1938/1991, p. 310). Often, we describe behavior by its effect on the environment and not by its topography. Thus, for example, we say “pick up the glass” and not “reach out the arm, open and close the hand,” and so on. Many different topographies can achieve the same effect, but any response must have a topography that is suitable to obtain reinforcement. An operant class is a class of topographies that are functionally related by its common consequences.

In the case of nonverbal behavior, the relation between the topography of responses and reinforcement is established by the mechanical and geometrical principles that describe relations among objects in general. In the case of verbal behavior, by contrast, the relation between the topography (sometimes referred to as pattern) of responses and reinforcement is established by the conventional practices of the verbal community (Skinner, 1957a, pp. 1–2). The conventions of a community are contingencies that in many aspects are similar for all the members of that community. For example, in order to get water, all speakers must emit a similar string of sounds Water, please! From the perspective of the listener, a complementary situation occurs: The sequence of sounds water is established as a discriminative stimulus for all the members of that community, and evokes similar responses modulated by the verbal and nonverbal context. By providing an explanation of the behavioral processes that condition the listener (how speech sounds produced by the speaker become discriminative stimuli for the listener) and the speaker (how the repertoire of verbal operants is built by the reinforcing actions of the listener), Skinner provides an explanation of how the linguistic conventions of the community are acquired.

In verbal behavior, the topographies selected are the ones that have an effect on the listener, those that were present in the verbal behavior of the persons with whom the listener interacted during his or her life. The criterion by which the environment selects the topography of the speaker's behavior (the criterion by which the listener or mediator presents the reinforcer) is conformity with the conventions of the verbal community, mainly the ones described by linguists as “languages.” According to Skinner,

The pattern of response which characteristically achieves the given reinforcement depends, of course, upon the “language”—that is, upon the reinforcing practices of the verbal community (1957a, p. 36)

They [the contingencies that prevail in a given verbal community] shape and maintain the phonemic and syntactical properties of verbal behavior and account for a wide range of functional characteristics—from poetry to logic. (Skinner, 1969, p. 12)

The distinction made by Skinner between verbal and nonverbal operant behavior is based on the different criteria by which the environment selects their respective topographies, as well as other dimensions of the response, and the definition of verbal behavior must specify the appropriate criterion. The main problem with the definition of verbal behavior as “behavior reinforced through the mediation of other persons [who] must be responding in ways which have been conditioned precisely in order to reinforce the behavior of the speaker” is that it does not focus on the defining property of the functional relation between verbal responses and consequences: Reinforcers follow responses that have the properties that are conventional in the practices of the verbal community. The mediator is just like the apparatus in experiments on nonverbal operant behavior: Both deliver reinforcers depending on the response having certain specified properties. The mediator and the apparatus are just vehicles for providing reinforcement.

The following definition might usefully combine most of the elements by which verbal behavior was conceived by Skinner: “Verbal behavior is operant behavior whose properties are selected by the reinforcing action of a mediator8 on the basis of their correspondence to the conventions of a community.” A definition focused not just on the mediator but also on the basis of the selective action of the reinforcement that is specific to verbal behavior makes us more attentive to the conventions from which languages and other symbolic systems are constructed as the main part of the contingencies of reinforcement that shape and maintain verbal behavior. Several immediate consequences might follow from this definition:

The specification of a clearer criterion for the distinction between verbal and nonverbal behavior, including the distinction between most cases of behavior of experimental animals and speech, something that has been lacking in the field until now. This criterion does not conflict with Skinner's definition (in both versions, the refined and unrefined ones) and is consistent with Skinner's writings about the relations between verbal behavior and the practices of verbal communities.

A theoretical approximation to the field of linguistics and its conception of language as an arbitrary system of signs by which linguists mean anchoring language in the conventions of a community (Passos, 2007). Historically, languages have been seen as arbitrary, also called conventional, systems of signals. In the philosophy of language and linguistics, when scholars highlight the conventional nature of language, they mean that (a) there is no natural causal connection (e.g., between smoke and fire) or relation of sameness (e.g., between a thing and its image) between the sounds of language and their meanings; rather, these sounds are connected to their meanings through the conventions of a community. Unlike natural connections, conventional connections differ in space and time, as we can see by the simple fact that the same object is called table in English, mesa in Portuguese, and mensa in Latin. Linguists describe the conventions of linguistic (also called speech) communities at several different levels: phonological, lexical, syntactical, pragmatic (Crystal, 1997, pp. 82–83); (b) language is a form of action that works indirectly on the environment by functioning as stimuli for listeners who act directly on the environment. The relation between these stimuli and their meanings is established by the conventions of a community (Bloomfield, 1933/1961, pp. 22–27, 38–39, 144–147).

The search for accurate descriptions of these conventions when planning experimental procedures. Because linguistic descriptions specify the patterns of sounds and their related meanings, as observed in the languages of communities, they provide important elements for the design of contingencies by behavior analysts. People in general, including behavior analysts, are often misguided by the description of language learned in school, the shortcomings of which have been described by Bloomfield and other linguists. This description is guided in part by the written forms of the language, which represent speech imperfectly (Bloomfield, 1914, p. 22, 1942). With the goal of a better representation, linguists devised phonetic alphabets, like the International Phonetic Alphabet. Studies devised to build a repertoire of textual behavior teach the relation of written forms of the language to their spoken forms (Bloomfield, 1942; Skinner, 1957a, pp. 65–69). To correctly analyze this relation, the spoken forms should be written in a phonetic alphabet,9 which is rarely used by behavior analysts. The lack of phonetic representation in behavior-analytic studies may make it difficult for other researchers to comprehend the experimental procedure if they do not know the language being taught in the experiment. They will be unable to figure out how the words used as stimuli sound. Linguistic description of many phonological, morphological, and syntactical aspects, as well as the ones described by linguistic pragmatics, are also valuable when programming verbal contingencies.

I began this paper by quoting a few lines by the wonderful Brazilian poet Manoel de Barros. I understand these lines as expressing the poet's wonder and love for language, the substance of his craft, and from which he receives the gift of feeling free from the constraints of a world regulated by natural laws. Skinner showed that what the poet found to be so singular about language is partially true but needs qualification. Language does not depart from the “natural order of things”; it is rather the very part of natural phenomena that result mainly from social interaction regulated by the conventions of a group. By taking into account these conventions and the principles of operant and classical conditioning, Skinner was the first scientist to find orderly and predictable relations in the realm of the speech of the individual and the behavior of the listener.

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful to David A. Eckerman and Ernest A. Vargas for their careful reading of an earlier version of this paper. I did my best to incorporate their wise suggestions into the paper.

Footnotes

Só as palavras não foram castigadas com a ordem natural das coisas. As palavras continuam com seus deslimites. Translation from Portuguese into English is mine. The word deslimites is a neologism in Portuguese, as the word unlimit, coined to translate it, is a neologism in English.

These lectures, reproduced in written form and made available to the participants, were used in the preparation of Verbal Behavior (p. vii). After Verbal Behavior, they are the most important source for the study of Skinner's approach to this subject matter. The B. F. Skinner Foundation website (http://www.bfskinner.org/BFSkinner/Home.html) offers an electronic version of them.

We find the same kind of criticism of normative grammarians in the work of many linguists. In his famous Language (1933/1961), read by Skinner (1934), Bloomfield had also called these grammarians authoritarians: “This [the spread of education in the 18th century] gave the authoritarians their chance: they wrote normative grammars, in which they often ignored actual usage in favor of speculative notions. Both the belief in ‘authority’ and some of the fanciful rules (as, for instance, about the use of shall and will) still prevail in our schools” (p. 7).

Correcting by hand the typed letter, Skinner crossed out the word defining twice, handwrote restricting in its place, and added a comma after inflection. I thank Julie S. Vargas for helping me to understand Skinner's handwriting.

Because the word grammar has many meanings (see a few of them in Crystal, 1997, p. 88), to avoid misunderstanding based on polysemy, it is a healthy scholarly practice to specify what the word means in each occasion.

Fowler's (1930) Modern English Usage is referred to five times in Skinner's Verbal Behavior (pp. 72, 235, 252, 271, 395). None of these citations are made to promote a prescriptive point of view but rather to use Fowler's description of English.

This text is the result of stenographic notes taken by Ralph Hefferline of a course on verbal behavior taught by Skinner at Columbia University in the summer of 1947. The B. F. Skinner Foundation website (http://www.bfskinner.org/BFSkinner/Home.html) offers an electronic version of it. I thank Gerson Y. Tomanari for sending me a copy of it many years ago.

I thank Ernest Vargas (personal communication) for suggesting the use of “mediator” instead of “listener” because the word “mediator” (a) has no commitment to any specific kind of verbal behavior (be it vocal, tactile, visual, etc.) whereas “listener” is more restrictive because it implies that the product of verbal behavior is auditive, and (b) stresses the function of this participant in the act of speech.

The purpose of this phonetic representation is just that the researcher will have a more accurate representation of the spoken form. The phonetic representation is not intended to be shown to the participants, because what they are supposed to learn is the relation of the form written in the regular alphabet to the spoken form.

REFERENCES

- Alter S.G. William Dwight Whitney and the science of language. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Arntzen E. Interview with Julie S. Vargas. European Journal of Behavior Analysis, 12. 2010;2:199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Bjork D.W. B. F. Skinner: A life. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Linguistics and reading. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1942. pp. 384–395. (Ed.) (Reprinted from Elementary English Review, 19, 125–130, 183–186) [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Language. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston; 1961. (Original work published 1933) [Google Scholar]

- Burchfield R.W, Fowler H.W. The new Fowler's modern English usage (3rd ed.) Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Catania A.C. Learning (4th ed.) Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman S.R. B. F. Skinner, 1926–1928: From literature to psychology. The Behavior Analyst. 1985;8:77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Crystal D. A first dictionary of linguistics and phonetics. London: Deutsch; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Crystal D. The Cambridge encyclopedia of language (2nd ed.) Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Crystal D. Introduction. In: Fowler H.W, Crystal D, editors. A dictionary of modern English usage. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009a. pp. vii–xxiv. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Crystal D. Note on the text. In: Fowler H.W, Crystal D, editors. A dictionary of modern English usage. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009b. xxv. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- de Barros M. Retrato do artista quando coisa (4th ed.) Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Record; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler H.W. A dictionary of modern English usage. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1930. Entry “that rel. pron.”. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C, Blackledge J.T, Barnes-Holmes D. Language and cognition: Constructing an alternative approach within the behavioral tradition. In: Hayes S.C, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B, editors. Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2001. pp. 3–20. (Eds.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jespersen O. Language. London: Allen & Unwin; 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Koerner E.F.K. Editor's foreword. In: Wegener P, Koerner E.F.K, editors. Untersuchungen über die Grundfragen des Sprachlebens. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins; 1991. pp. v*–vii*. (Eds.) Amsterdam studies in the theory and history of linguistic science, Vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Kolln M. Understanding English grammar. New York: MacMillan; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Leigland S. Is a new definition of verbal behavior necessary in light of derived relational responding? The Behavior Analyst. 1997;20:3–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03392757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone J.C., Jr Operants were never “emitted,” feeling is doing, and learning takes only one trial: A review of B. F. Skinner's Recent Issues in the Analysis of Behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1999;71:115–120. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1999.71-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos M.A, Passos M.L.R.F. Emergent verbal behavior and analogy: Skinnerian and linguistic approaches. The Behavior Analyst. 2010;33:65–81. doi: 10.1007/BF03392204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson A, Bonem M, Green G, Osborne J.G. A citation analysis of the influence on research of Skinner's Verbal Behavior. The Behavior Analyst. 1984;7:157–167. doi: 10.1007/BF03391898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael J, Malott R.W. Michael and Malott's dialogue on linguistic productivity. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2003;19:115–118. doi: 10.1007/BF03392985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller F.M. Lectures on the science of language (2nd London ed., rev.) New York: Scribner; 1884. (Original work published 1861) [Google Scholar]

- Nerlich B, Clarke D.D. Language, action, and context: The early history of pragmatics in Europe and America, 1780–1930. Amsterdam studies in the theory and history of linguistic science, Vol. 80. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Normand M.P. Much ado about nothing. The Behavior Analyst. 2009;32:185–190. doi: 10.1007/BF03392182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne J.G. Beyond Skinner? A Review of Relational Frame Theory: A Post-Skinnerian Account of Human Language and Cognition by Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, and Roche. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2003;19:19–27. doi: 10.1007/BF03392979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima A, Hogue A. Writing academic English (2nd ed.) 1991. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer D.C. On Skinner's definition of verbal behavior. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy. 2008;8:295–307. [Google Scholar]

- Passos M.L.R.F. Skinner's definition of verbal behavior and the arbitrariness of the linguistic signal. Temas em Psicologia. 2007;15:161–172. Retrieved from http://www.sbponline.org.br/revista2/vol15n2/v15n2a03te.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Passos M.L.R.F. Linguistics and the concept of autoclitic. 2010, June. In S. S. Tanaka (Chair), Interdisciplinary investigations in behavior analysis and linguistics. Symposium conducted at the annual convention of the Association for Behavior Analysis, San Antonio. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson G.B. A day of great illumination: B. F. Skinner's discovery of shaping. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2004;82:317–328. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2004.82-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. 1934, July 2. [Letter to Fred Keller]. Original in possession of Julie S. Vargas. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. A psychological analysis of verbal behavior. 1947. Transcription by R. Hefferline of Skinner's course on verbal behavior at Columbia University, New York. Harvard University Archives (Papers of Burrhus Frederic Skinner, 1928–1979, Call HUG(FP) 60.50, Box 3, Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. William James lectures. 1948. Mimeograph copies of the original transcripts, published by the Association of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, Western Michigan University. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Skinner B.F, Laties V.G, Catania A.C the B. F. Skinner Foundation. Cumulative record. Acton, MA: Copley; 1999. A critique of psychoanalytic concepts and theories. pp. 285–294. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. 1954b, September 23. [Letter to the editor of The Scientific Monthly]. Harvard University Archives (Papers of Burrhus Frederic Skinner, 1928–1979, Call HUG(FP) 60.10, Box 2, Folder Transfer files 1956–1957), Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Verbal behavior. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1957a. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. 1957b, April 3. [Letter to the editors of Science]. Harvard University Archives (Papers of Burrhus Frederic Skinner, 1928–1979, Call HUG(FP) 60.10, Box 2, Folder 1956–1957), Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. 1959, June 29. [Letter to Richard Bruner]. Harvard University Archives (Papers of Burrhus Frederic Skinner, 1928–1979, Call HUG(FP) 60.10, Box 3, Folder Transfer files 1959), Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. B. F. Skinner. In: Boring E.G, Lindzey G, editors. A history of psychology in autobiography (Vol. 5, pp. 387–413) New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1967. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Contingencies of reinforcement: A theoretical analysis. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Particulars of my life. New York: Knopf; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. A matter of consequences. New York: Knopf; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Upon further reflection. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. The behavior of organisms. Acton, MA: Copley; 1991. (Original work published 1938) [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Skinner B.F. Cumulative record (definitive ed., V. G. Laties & A. C. Catania, Eds., pp. 165–175) Cambridge, MA: B. F. Skinner Foundation; 1999. Reinforcement today. (Original work published 1958) [Google Scholar]

- Tieken-Boon O.I. Henry Fowler and his eighteenth-century predecessors. The Henry Sweet Society Bulletin. 2008;51:5–24. Retrieved from http://www.henrysweet.org/bulletin_nov2008.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Wegener P. Abse D.W. Speech and reason. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia; 1971. The life of speech (D. W. Abse, trans.). pp. 111–293. (Original work Untersuchungen ueber die Grundfragen des Sprachlebens. Halle: Max Niemayer) [Google Scholar]