Abstract

Aims

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a strong predictor of adverse events with an incompletely understood pathophysiology. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) is proposed as an early marker of renal tubular injury. Our aim is to determine whether AKI during treatment of acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) is accompanied by renal tubular injury.

Methods and results

Urinary NGAL (uNGAL) and urinary creatinine (uCreat) levels were measured in 141 consecutive patients hospitalized for ADHF and followed for 180 days for death or re-hospitalization. AKI was defined as a rise in serum creatinine ≥0.3 mg/dl in a 48 h period. Median uNGAL/uCreat levels on Day 1 (baseline) were similar between patients who did and did not develop AKI [22.8 (12.5–106.8) μg/g vs. 20.6 (12.4–52.0) μg/g, P = 0.55]. On Day 2 and beyond, the difference between the AKI and no AKI cohorts increased, but was only significant on Day 3 [36.2 (21.7–131.8) μg/g vs. 29.4 (11.4–54.6) μg/g, P = 0.02]. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for Day 2 uNGAL/uCreat (≥ or <32 µg/g) to predict AKI was 0.61. There was no difference in diuretic response between ‘uNGAL/uCreat + ’ (≥ 27 µg/g) and ‘uNGAL/uCreat–’ (<27 µg/g) patients. However ‘uNGAL/uCreat + ’ patients had more adverse events after 180 days (66% vs. 52%, P = 0.02).

Conclusions

In patients with ADHF who develop AKI following diuretic therapy, a minor rise in uNGAL precedes AKI. However, the degree of renal tubular insult was much lower than that observed in other forms of AKI.

Keywords: Acute decompensated heart failure, Cardio-renal syndrome, Diuretics, NGAL, Tubular injury

Introduction

The occurrence of acute kidney injury (AKI) during the treatment of acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF; often referred to as the acute or Type 1 ‘cardio-renal syndrome’) is a frequently encountered problem.1,2 It often necessitates the clinician cutting back on diuretics, resulting in incomplete decongestion. Although certain subgroups with a better prognosis exist, AKI is predictive of overall adverse clinical outcomes.3,4 Although the exact pathophysiology of this cardio-renal interaction is still unclear, it is often considered a ‘pre-renal’ phenomenon in the absence of intrinsic kidney damage as a result of a reduction in kidney perfusion due to either arterial underfilling or increased renal outflow impedance secondary to venous congestion.5–7 There are probably subsets of patients where renal tubular injury or necrosis may occur. Hence, there is a need for early non-invasive biomarkers to better guide decongestive strategies.

Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) is a 25 kDa protein normally secreted by renal tubular cells, leucocytes, and several other types of epithelial cells in response to ischaemic or toxic injury.8,9 It is freely filtered by the glomerulus and subsequently reabsorbed in the proximal tubules.10 Its plasma concentration is thus dependent on the production in different organs and cells and on the glomerular filtration rate and proximal tubular function, whereas the urinary concentration is largely a consequence of the production of NGAL in distal nephron segments. Both plasma and urinary NGAL have been shown to be early predictors of AKI in a number of different clinical scenarios such as post-cardiac surgery, kidney transplantation, contrast nephropathy, intensive care admission, and for all comers in the emergency department.11–16 The assay recently became available for commercial use in Europe. Higher serum concentrations of NGAL on admission were associated with incident development of AKI during treatment for ADHF.17 However, systemic levels of NGAL were largely determined by renal impairment as opposed to the degree of myocardial dysfunction, despite the up-regulation of NGAL in failing cardiomyocytes itself.18 Urinary concentrations are elevated in chronic heart failure as compared with normals.19,20 In the acute setting, urinary NGAL (uNGAL) seemed to distinguish between true ‘intrinsic’ renal tubular injury and pre-renal azotaemia.13,21 The primary aim of this prospective, multicentre study is to better characterize the evolution of uNGAL trends and their relationships with AKI during decongestive treatment for ADHF and adverse long-term clinical outcomes.

Methods

Patient population

Patients with a primary diagnosis of ADHF, admitted to one of two hospitals of the Cleveland Clinic Health System (Cleveland Clinic Main Campus and Fairview General Hospital), were eligible for enrolment in the study within 24 h of presentation. Further inclusion criteria were: (i) age ≥18 years; (ii) clinical evidence of congestion including but not limited to presence of jugular venous distension, pulmonary rales, peripheral oedema, or ascites; and (iii) planned strategy for treatment with intravenous furosemide. Exclusion criteria were: (i) acute coronary syndromes; (ii) end-stage renal disease on renal replacement therapy; (iii) known exposure to nephrotoxic agents (such as contrast dye); (iv) planned surgery at the time of enrolment; and (v) haemoglobin <9 mg/dL or active bleeding.

Study design

This prospective cohort study was approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board and all subjects provided written consent. After enrolment, the first samples of urine and venous blood were obtained for the measurement of uNGAL and serum creatinine, respectively (Day 1 value). The uNGAL levels were corrected for urinary creatinine (uCreat). These measurements were repeated daily for 5 days, or until discharge, whichever came first. Urine output was recorded during the entire study period and expressed in 24 h periods. Subject demographics and clinical history, relevant co-morbidities, and documented left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction within the past 3 months were collected upon enrolment. AKI was defined as a ≥0.3 mg/dL rise in serum creatinine in a 48 h time period during the first 5 days of hospitalization, consistent with previous studies.22,23 Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the standard four-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation. Treatment regimens of the subjects, including timing, dosage, and route of the diuretic therapy, were at the discretion of the treating physicians.

Clinical endpoints

After discharge, patients were prospectively followed for adverse clinical events (all-cause mortality and re-hospitalization) up to 180 days after discharge. All-cause mortality was determined by telephone contact, manual chart review, and later confirmed by Social Security Death Index.

Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin measurements

Urinary samples were assessed in batch samples using the Abbott ARCHITECT ci8200 immunoassay platform (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA). High affinity antibodies were generated towards distinct epitopes on NGAL, and assay standards were prepared using human recombinant NGAL. The assay is a two-step (sandwich) assay using chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay technology. This assay has a functional sensitivity of <2 ng/mL with a total coefficient of variation <10%. Baseline brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) was also measured by a clinically available assay in the same platform.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ±standard deviation if normally distributed or as median and interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed data. Normality was assessed by the Shapiro–Wilk W test. Categorical data were summarized as proportions and frequencies. Univariate comparisons of these variables were performed between patients who developed AKI and those who did not, using the Student t-test for normally distributed variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for non-normally distributed variables. For categorical data, χ2 or Fisher exact test were used for appropriate comparisons. Spearman's rank correlation method was used as a non-parametric measure of association for correlations between uNGAL, serum creatinine, eGFR, and BNP. The evolution of uNGAL/uCreat during hospitalization was explored, using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. The predictive value of uNGAL/uCreat for AKI was assessed by the use of a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, thereby creating an optimal cut-off point for the prediction of AKI. Odds ratios were calculated through logistic regression analysis and evaluated according to the likelihood ratio test. A multivariate logistic regression model was constructed using variables that have previously been proven to predict AKI (age, systolic blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, and baseline renal function) in addition to those which were different at baseline between patients with vs. without AKI. Clinical outcome at 180 days was evaluated by Kaplan–Meier survival analyses. Differences between groups (AKI vs. no AKI; ‘uNGAL/uCreat + ’ vs. ‘uNGAL/uCreat–’) were evaluated with the log-rank test. Statistical significance was set at a two-tailed probability level <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP 9 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). All authors have read and agree to the manuscript as written. The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, all study analyses, the drafting and editing of the manuscript, and its final contents.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Between March 2009 and March 2010, 144 patients were prospectively enrolled in this study. Three patients were excluded due to incomplete data collected. The final study cohort thus encompasses 141 patients. The baseline characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1. AKI occurred in 35 of 141 patients (25%), after a mean of 2.9 ± 0.9 days of hospitalization. Notably, patients who developed AKI during hospitalization had a higher LV ejection fraction, higher statin use, and trended to be older and have a higher prevalence of ischaemic heart disease than those not experiencing AKI.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| No AKI (n = 106) | AKI (n = 35) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 72 (59–79) | 78 (67–81) | 0.06 |

| Male gender (%) | 62 | 46 | 0.11 |

| African American (%) | 20 | 6 | 0.06 |

| Co-morbidities | |||

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 41 | 54 | 0.17 |

| Hypertension (%) | 82 | 86 | 0.80 |

| Ischaemic (%) | 39 | 56 | 0.11 |

| HFpEFa (%) | 38 | 56 | 0.10 |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 40 | 50 | 0.33 |

| Clinical data | |||

| Baseline systolic BP | 132 ± 24 | 137 ± 19 | 0.34 |

| Echocardiographic data | |||

| LVEF (%) | 40 (25–55) | 55 (36–60) | 0.04 |

| Laboratory data | |||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.17 (0.95–1.54) | 1.29 (0.94–1.72) | 0.61 |

| eGFRb (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 65 (44–79) | 53 (30–72) | 0.11 |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 753 (299–1579) | 572 (187–1094) | 0.29 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 24 (17–34) | 27 (17–34) | 0.79 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.9 ± 1.8 | 11.7 ± 1.5 | 0.77 |

| Medications | |||

| ACE-I or ARB (%) | 51 | 47 | 0.70 |

| Beta-blockers (%) | 76 | 71 | 0.50 |

| Spironolactone (%) | 15 | 21 | 0.43 |

| Loop diuretic (%) | 73 | 68 | 0.52 |

| Hydralazine/nitrates | 30 | 24 | 0.66 |

| Digoxin (%) | 22 | 18 | 0.81 |

| Statin (%) | 48 | 74 | 0.01 |

ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; AKI, acute kidney injury; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; BP, blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

aHFpEF was defined as an LVEF >50%.

beGFR was calculated with the four-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation.

Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin levels during treatment for acute decompensated heart failure

Overall, patients with ADHF experienced relatively low uNGAL/uCreat levels. Median uNGAL and uNGAL/uCreat concentrations at baseline (Day 1) were 9 (4.2–27.2) ng/mL and 22.6 (12.5–66.9) μg/g, respectively. Concentrations of uNGAL rose significantly on Day 2 [15 (5.4–42.6) ng/mL, P < 0.0001], Day 3 [19.4 (6.6–42.3] ng/ml, P = 0.0007], Day 4 [16.3 (7.1–37.6) ng/mL, P = 0.056], and Day 5 [21.9 (8.8–50.0) ng/mL, P = 0.007] as compared with the baseline value on Day 1. However, when corrected for uCreat, these increases were no longer significant, indicating that part of the observed difference in uNGAL concentrations is explained by urinary dilution [Day 2, 29.4 (12.8–66.3) μg/g, P = 0.19; Day 3, 33.7 (18.0–112.4) μg/g, P = 0.24; Day 4, 27.4 (15.8–88.6) μg/g, P = 0.14; and Day 5, 21.9 (8.8–50.0) μg/g, P = 0.06 as compared with the baseline value on Day 1]. In our study cohort, baseline uNGAL did not correlate with baseline creatinine (r = 0.05, P = 0.57), baseline eGFR (r= –0.10, P = 0.22), or baseline BNP (r = –0.08, P = 0.33).

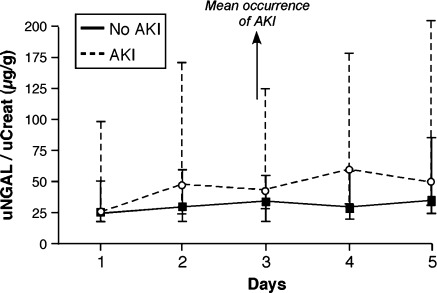

On Day 1, median uNGAL/uCreat levels were not significantly different between those with vs. without AKI [22.8 (12.5–106.8) vs. 20.6 (12.4–52.0) μg/g, P = 0.55] (Figure 1). On Day 2 and beyond, the difference between the AKI and no AKI cohorts increased but was only significant on Day 3 [Day 2, 42.0 (13.5–154.3) vs. 26.2 (11.9–60.3) μg/g, P = 0.06; Day 3, 36.2 (21.7–131.8) vs. 29.4 (11.4–54.6) μg/g, P = 0.02; Day 4, 52.4 (19.0– 60.8) vs. 24.3 (15.1–59.3) μg/g, P = 0.06; and Day 5, 42.9 (21.0–194.1) vs. 30.5(16.2–88.4) μg/g, P = 0.17) (Figure 1). The median rise in uNGAL/uCreat from Day 1 to Day2 was significantly higher in patients who developed AKI afterwards (+4.4 vs. –0.3 µg/g, P = 0.04).

Figure 1.

Serial uNGAL/uCreat levels in acute decompensated heart failure. Evolution of uNGAL/uCreat levels from Day 1 to Day 5 stratified by the presence (dashed line) or absence of AKI (solid line). Error bars represent the interquartile range. AKI, acute kidney injury; uCreat, urinary creatinine; uNGAL, urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin.

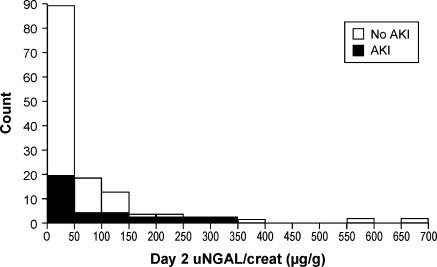

Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin/urinary creatinine levels for the prediction of acute kidney injury

Figure 2 shows the distribution of uNGAL/uCreat on Day 2, with the patients who subsequently developed AKI vs. no AKI. An ROC curve was constructed for uNGAL/uCreat based on Day 2 levels. The area under the ROC curve (AUC-ROC) was only 0.61. A cut-off value of 32 µg/g at Day 2 resulted in sensitivity and specificity of 64% and 58%, respectively .

Figure 2.

Distribution of uNGAL/uCreat levels on day 2. AKI, acute kidney injury; uCreat, urinary creatinine; uNGAL, urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin.

Diuretic response and dosing

All patients received intravenous furosemide as their diuretic therapy. The administered intravenous furosemide dose on Day 1 was not significantly different between patients who developed AKI or those who did not (129 ± 118 vs. 107 ± 93 mg/day respectively, P = 0.26). However, as expected, the initial (Day 1) diuretic response was different between AKI and no AKI [1550 (501–2275) vs. 1988 (983–3724) mL/day, respectively, P = 0.02]. After Day 1, there was a trend towards the use of higher doses of furosemide in AKI patients. To explore whether elevated uNGAL levels influenced diuretic response, all patients were dichotomized in a ‘uNGAL + ’ and an ‘uNGAL–’ group according to their median uNGAL value (15.5 ng/mL) over the 5 day period. Figure 3 demonstrates that uNGAL+ patients had a lower diuresis. However, when corrected for uCreat (uNGAL/uCreat ≥ or <27 µg/g), these differences were no longer significant, indicating that the lower uNGAL levels were mainly the result of dilution due to increased diuresis.

Figure 3.

Diuretic response stratified by uNGAL and uNGAL/uCreat levels. Average diuretic response according to ‘uNGAL + ’ vs. ‘uNGAL–’ (A) and ‘uNGAL/uCreat + ’ vs. ‘uNGAL/uCreat–’ (B) patients in the total cohort and in patients with and without AKI. AKI, acute kidney injury; uCreat, urinary creatinine; uNGAL, urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin.

Comparing urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin with other predictors of acute kidney injury

To explore the value of Day 2 uNGAL/uCreat in predicting AKI, logistic regression was performed for different baseline characteristics of interest. In our patients, statin use and high LV ejection fraction were significant predictors of AKI in univariate analysis. The increase in uNGAL/uCreat from Day 1 to Day 2 was on the edge of significance. In multivariate analysis, however, none of the univariate predictors remained significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression for the prediction of acute kidney injury

| Risk factor | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | ||

| Age | 1.45 (0.98–2.24) | 0.07 |

| Female gender | 1.96 (0.91–4.29) | 0.09 |

| Baseline systolic BP | 0.79 (0.49–1.28) | 0.34 |

| Changes in systolic BPa | 0.68 (0.41–1.11) | 0.12 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.74 (0.81–3.80) | 0.16 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 2.01 (0.92–4.44) | 0.08 |

| Statin use | 3.01 (1.31–7.42) | 0.009 |

| LV ejection fraction | 1.58 (1.04–2.47) | 0.03 |

| Baseline eGFR | 0.74 (0.48–1.09) | 0.13 |

| Baseline creatinine | 1.24 (0.78–1.64) | 0.46 |

| Day 1 uNGAL/uCreat | 1.02 (0.62–1.47) | 0.90 |

| Day 2 uNGAL/uCreat | 1.36 (0.95–2.03) | 0.09 |

| Day 2 uNGAL/uCreat ≥32.2 µg/g | 1.87 (0.85–4.22) | 0.12 |

| ΔuNGAL/uCreatb | 1.77 (1.00–3.76) | 0.05 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||

| Age | 1.7 (0.84–3.82) | 0.14 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.12 (0.67–7.19) | 0.20 |

| Baseline systolic BP | 1.08 (0.62–1.85) | 0.79 |

| Statin use | 2.27 (0.66–8.98) | 0.20 |

| LV ejection fraction | 1.77 (0.90–3.76 | 0.10 |

| Baseline eGFR | 0.89 (0.5–1.52) | 0.66 |

| Change in uNGAL/uCreatb | 1.27 (0.72–3.71) | 0.51 |

Odds ratio reported per 1-SD increment for continuous variables (1-SD for age = 12.5 years; 1-SD for EF = 17.5 %; 1-SD for baseline eGFR = 26.09mL/min/1.73 m2; 1-SD for baseline creatinine = 0.65 mg/dL; 1-SD for Day1 uNGAL/uCreat = 154 µg/g; 1-SD for Day2 uNGAL/uCreat = 121 µg/g; 1-SD for ΔuNGAL/uCreat = 112 µg/g.

BP, blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LV, left ventricular; uNGAL, urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; uCreat, urinary creatinine.

aDifference between Day 2 and Day 1.

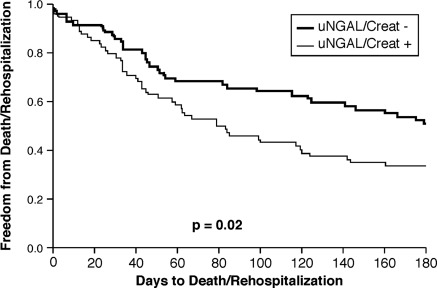

Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin and acute kidney injury as predictors of 180 day outcome

Over a follow-up of 180 days, there were 22 deaths (15.6%) and 79 patients had a re-hospitalization (56%). The reason for re-hospitalization was documented in 89% of patients, with heart failure being the principal diagnosis in 58% of patients. Taking as a composite endpoint death or re-hospitalization at 180 days, there was no difference between patients who experienced AKI during the index hospitalization and those who did not (54% vs. 61%, respectively, P = 0.27). When patients were dichotomized according the their median daily uNGAL/uCreat value, however, ‘uNGAL/uCreat + ’ patients had a higher event rate than ‘uNGAL/uCreat–’ patients (66% vs. 53%, P = 0.02) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier curve for 180 day outcome, Outcomes (death or re-hospitalization) stratified by median ‘uNGAL/uCreat’ (n = 71 for ‘ + ’ and n = 70 for ‘–’ group) during the index hospitalization. AKI, acute kidney injury; CHF, chronic heart failure; uCreat, urinary creatinine; uNGAL, urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin.

Discussion

The key finding of this study is that diuretic therapy to relieve congestion in ADHF is accompanied by a lack of a significant rise in a marker of renal tubular injury, uNGAL, despite the presence of AKI in a subset of subjects. Secondly, this overall uNGAL rise is only slightly more pronounced among those who subsequently develop AKI, and remains far lower than the diagnostic range of uNGAL (and uNGAL/uCreat) in the setting of other types of AKI (often ≥130 µg/g creatinine).13 Thirdly, elevated uNGAL/uCreat levels are associated with worse outcomes (death or heart failure rehospitalization at 180 days). Taken together, our findings imply that the pattern and extent of renal tubular injury associated with ADHF (as indicated by a rise in uNGAL) may be distinctively different from those of other forms of AKI (such as in contrast nephropathy). In other words, the presence of AKI in the setting of aggressive diuresis may not necessarily reflect underlying renal tubular injury.

The pathophysiology of renal insufficiency and AKI in patients with heart failure is still incompletely understood. Because cardiac dysfunction induces renal impairment and vice versa, the co-occurrence of these pathologies exceeds what is expected solely on the basis of common aetiologies such as diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Lately, attention has shifted somewhat from cardiac output (‘forward failure’) to venous congestion (‘backward failure’) as the important haemodynamic determinants.5,7 Nevertheless, insufficient renal perfusion (‘pre-renal’) as a result of intravascular salt and water removal by diuretic therapy remains the most frequently cited mechanism to explain reductions in eGFR. However, renal dysfunction in heart failure goes beyond glomerular filtration. In recent years, some authors have demonstrated the presence of renal tubular injury, as judged by urine biomarkers such as NGAL, N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase (NAG), and kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM-1), in patients with heart failure.20,24 We describe minor elevations in uNGAL levels during treatment of ADHF with intravenous diuretics and vasodilators on a background of contemporary heart failure medications. These elevations tend to be more pronounced in patients who subsequently develop AKI, despite no significant differences at baseline. However, the uNGAL levels in our study cohort were far lower than those observed in ‘typical’ acute renal tubular necrosis situations (such as post cardio-pulmonary bypass, contrast nephropathy, and intensive care admissions). This is consistent with the fact that few patients develop true injury or failure by RIFLE criteria despite the fact that one out of four patients developed a rise in serum creatinine. Hence, the majority of patients with ADHF who experience AKI during aggressive diuretic therapy to relieve congestion may have no evidence of underlying renal tubular injury (at least in terms of the severity that parallels other forms of AKI). While some may argue that the lack of rising uNGAL or uNGAL/uCreat may provide incremental insight into a potentially reversible form of renal impairment, the clinical utility of routine uNGAL testing in the setting of ADHF may be challenged if the majority of patients do not demonstrate elevated levels or if there is a wide range of overlap between those with vs. without adverse outcomes.

In contrast to our previous study looking at the predictive value of serum NGAL in ADHF,17 we found that baseline (Day 1) uNGAL levels did not predict AKI, and the rise in uNGAL is fairly modest. One explanation of this discrepancy may lie in differences in the populations being studied. The current study cohort has a median age of 72 years, median LV ejection fraction of 43%, and median baseline serum creatinine of 1.18 mg/dL (mean 1.35 mg/dL)—representing the broader heart failure patient population with impaired as well as preserved systolic function in a multicentre study. This is in contrast to our previous report looking at a population with more advanced systolic heart failure with greater cardio-renal compromise at baseline (mean age of 62 years, mean LV ejection fraction of 32%, and mean baseline serum creatinine of 1.6 mg/dL).17 Another important distinction between the two studies is the utilization of different sample types for NGAL measurements that are often considered equivalent but in reality may represent different aspects of renal dysfunction. According to the two-compartment model of NGAL traffic and activity, systemic and urinary NGAL may represent distinct sources.10,25 Urinary NGAL seems to be the result of NGAL produced by distal nephron segments in response to injury. In contrast, systemic NGAL is proposed to arise from extrarenal production as a result of inflammation and oxidative stress. Since systemic NGAL is almost completely reabsorbed by the proximal tubuli after filtration (<0.2% appears in the urine), and because locally synthesized renal NGAL is not efficiently introduced into the circulation,10 these two ‘pools’ of NGAL seem to result from a distinctively different underlying pathophysiology. Such differences may not be as apparent in patient populations with no pre-existing renal insufficiency (such as in paediatric patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass), but in the setting of ADHF the values may vary widely due to underlying cardio-renal compromise at the time of presentation. As both serum and urine NGAL testing are currently under development, the similarities and differences as well as clinical significance of these values in ADHF will require further investigations.

We also explored whether renal tubular injury in the setting of AKI during decongestive therapy may alter diuretic responses. The rationale for this is that enhanced activities of both the Na+–K+–2Cl− co-transporter and the Na+–H+ exchanger in the thick ascending limb and epithelial sodium channels in the distal tubule cells have been observed as a response to renal tubular injury. This can be caused by local renal inflammation through production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and pro-oxidant free radicals accompanying renal tubular injury.26–27 When we divided patients into a uNGAL+ and uNGAL– group, based on their uNGAL levels over the 5 day period, there was a higher diuresis in the uNGAL– group. However, when corrected for uCreat, this difference disappeared, indicating that lower NGAL levels were the result of urinary dilution. It is important to point out that overall our population has demonstrated relatively large volume diuresis in response to diuretic therapy, with few subjects experiencing oliguria (unlike other forms of AKI where oliguria may be more prevalent). Hence these observations may further imply that in the presence of adequate urine output (i.e. adequate diuresis as a result of natriuresis), the degree of renal tubular injury was modest and unlikely to have impacted diuretic responses during ADHF therapy.

Although this study was designed as a mechanistic study and did not power for outcome measures, ‘uNGAL/uCreat + ’ patients had significantly more events than ‘uNGAL/uCreat–’ patients. These findings confirm the results from a recent meta-analysis and the GALLANT study even though the cut-off value was relatively low and urine levels were used instead of serum levels.11,28 It is unclear if such heightened risk is reflective of underlying progressive intrinsic renal disease vs. reversible cardio-renal compromise. Hence, further investigations regarding the impact of different treatment modalities in reducing long-term risk in patients with elevated uNGAL/uCreat are warranted.

The potential effects of decongestive treatment with diuretics and vasodilators on renal tubular integrity is complex. Some have postulated that there could be a direct toxic renal tubular effect of the treatment, while others have suggested a potential consequence of decreased renal perfusion. On the one hand, loop diuretics may increase the partial pressure of oxygen in the renal medulla by inhibiting energy-consuming transport activity;29 while at the same time, diuretics may directly reduce proximal tubular injury (as judged by a decrease in urinary NAG and KIM-1) by alleviating congestion.30 On the other hand, decongestive treatment with loop diuretics may adversely activate both the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) and the sympathetic nervous system as a result of intravascular depletion, thereby reducing renal blood flow leading to renal tubular injury.31,32 A similar bivalent feature of loop diuretics was recently suggested in a post-hoc analysis from the Beta-Blocker Evaluation of Survival Trial (BEST) trial.33 Renal tubular injury in and of itself can substantially decrease glomerular filtration by a tubulo-glomerular feedback mechanism, and may not require frank acute renal tubular necrosis to occur. This physiological–pathological dissociation is well known to nephrologists,34 and may be analogous to the presence and absence of myocardial necrosis in the setting of unstable angina and acute myocardial infarction, respectively. Findings from the present study at least reassure us that a routine decongestive strategy with diuretics and/or vasodilators in a typical elderly heart failure population is not associated with significant renal tubular injury despite the occurrence of AKI. Better mechanistic understanding of cardio-renal interactions leading to renal tubular injury and/or AKI is warranted to facilitate more effective decongestive therapy in the setting of ADHF.

Study limitations

The underlying idea of this study is to investigate the relationship between renal tubular injury (as measured by uNGAL) and AKI in the setting of ADHF. Since a direct anatomical–pathological study of renal tubular injury is not feasible, the presence of renal tubular injury was demonstrated by the evolution of a biomarker, which remains a surrogate measure. In addition, we lacked imaging data to determine the underlying intrinsic renal or renovascular disease. Secondly, since enrolment was allowed within 24 h of presentation, uNGAL levels on Day 1 could be influenced by exposure to initial diuretic treatment even though levels were uniformly low. In fact, our finding of the majority of subjects with a lack of rise in uNGAL at baseline argued against any pre-treatment confounding effects. Thirdly, the relatively small sample size precluded meaningful comparison of adverse clinical outcomes, and the potential prognostic utility of uNGAL as observed in prior studies of AKI should be further investigated in larger cohorts. Fourthly, our results apply to a heart failure population as studied, which is an older population with a fair amount of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and without evidence of low output. Whether the results would be similar in sicker, more congested, and low-output subjects, often experiencing more severe deterioration of renal function requiring ultrafiltration, remains to be determined.

Conclusions

Urinary NGAL, a marker of renal tubular injury, rises slightly during diuretic treatment of ADHF in patients who subsequently develop AKI. However, the degree of renal tubular insult and its predictive ability was far lower than that observed in other forms of AKI.

Funding

Abbott Laboratories; the National Institutes of Health's Case Western Reserve University/Cleveland Clinic Clinical and Translational Sciences Collaborative (CTSA Award, NCRR/NIH UL1 RR02499); the Belgian American Educational Foundation (BAEF) (research grant to M.D.).

Conflict of interest: W.H.W.T. has received research support from Abbott Laboratories, and serves as a consultant to Medtronic Inc. and St. Jude Medical. All other authors have no conflict to declare.

References

- 1.Ronco C, McCullough P, Anker SD, Anand I, Aspromonte N, Bagshaw SM, Bellomo R, Berl T, Bobek I, Cruz DN, Daliento L, Davenport A, Haapio M, Hillege H, House AA, Katz N, Maisel A, Mankad S, Zanco P, Mebazaa A, Palazzuoli A, Ronco F, Shaw A, Sheinfeld G, Soni S, Vescovo G, Zamperetti N, Ponikowski P Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) consensus group. Cardio-renal syndromes: report from the consensus conference of the acute dialysis quality initiative. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:703–711. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang WH, Mullens W. Cardiorenal syndrome in decompensated heart failure. Heart. 2010;96:255–260. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.166256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krumholz HM, Chen YT, Vaccarino V, Wang Y, Radford MJ, Bradford WD, Howtiz RI. Correlates and impact on outcomes of worsening renal function in patients>or =65 years of age with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85:1110–1113. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)00705-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Testani JM, Khera AV, St John Sutton MG, Keane MG, Wiegers SE, Shannon RP, Kirkpatrcik JN. Effect of right ventricular function and venous congestion on cardiorenal interactions during the treatment of decompensated heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:511–516. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Damman K, van Deursen VM, Navis G, Voors AA, van Veldhuisen DJ, Hillege HL. Increased central venous pressure is associated with impaired renal function and mortality in a broad spectrum of patients with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:582–588. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ljungman S, Laragh JH, Cody RJ. Role of the kidney in congestive heart failure. Relationship of cardiac index to kidney function. Drugs. 1990;39(Suppl 4):10–421. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199000394-00004. discussion 2–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mullens W, Abrahams Z, Francis GS, Sokos G, Taylor DO, Starling RC, Young JB, Tang WH. Importance of venous congestion for worsening of renal function in advanced decompensated heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:589–596. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devarajan P. Biomarkers for the early detection of acute kidney injury. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2011;23:194–200. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328343f4dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mishra J, Mori K, Ma Q, Kelly C, Yang J, Mitsnefes M, Barasch J, Devarajan P. Amelioration of ischemic acute renal injury by neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:3073–3082. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000145013.44578.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt-Ott KM, Mori K, Li JY, Kalandadze A, Cohen DJ, Devarajan P, Barasch J. Dual action of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:407–413. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haase M, Devarajan P, Haase-Fielitz A, Bellomo R, Cruz DN, Wagener G, Krawczeski CD, Koyner JL, Murray P, Zappitelli M, Goldstein SL, Makris K, Ronco C, Martensson J, Martling CR, Venge P, Siew E, Ware LB, Ikizler TA, Mertens PR. The outcome of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin-positive subclinical acute kidney injury: a multicenter pooled analysis of prospective studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1752–1761. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mishra J, Dent C, Tarabishi R, Mitsnefes MM, Ma Q, Kelly C, Ruff SM, Zahedi K, Shao M, Bean J, Mori K, Barasch J, Devarajan P. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as a biomarker for acute renal injury after cardiac surgery. Lancet. 2005;365:1231–1238. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74811-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nickolas TL, O'Rourke MJ, Yang J, Sise ME, Canetta PA, Barasch N, Buchen C, Khan F, Mori K, Giglio J, Devarajan P, Barasch J. Sensitivity and specificity of a single emergency department measurement of urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin for diagnosing acute kidney injury. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:810–819. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-11-200806030-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siew ED, Ware LB, Gebretsadik T, Shintani A, Moons KG, Wickersham N, Bossert F, Ikizler TA. Urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin moderately predicts acute kidney injury in critically ill adults. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1823–1832. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollmen ME, Kyllonen LE, Inkinen KA, Lalla ML, Salmela KT. Urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin is a marker of graft recovery after kidney transplantation. Kidney Int. 2011;79:89–98. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bachorzewska-Gajewska H, Malyszko J, Sitniewska E, Malyszko JS, Dobrzycki S. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) correlations with cystatin C, serum creatinine and eGFR in patients with normal serum creatinine undergoing coronary angiography. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:295–296. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aghel A, Shrestha K, Mullens W, Borowski A, Tang WH. Serum neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) in predicting worsening renal function in acute decompensated heart failure. J Card Fail. 2010;16:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shrestha K, Borowski AG, Troughton RW, Thomas JD, Klein AL, Tang WH. Renal dysfunction is a stronger determinant of systemic neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin levels than myocardial dysfunction in systolic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2011;17:472–478. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Damman K, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Navis G, Vaidya VS, Smilde TD, Westenbrink BD, Bonventre JV, Voors AA, Hillege HL. Tubular damage in chronic systolic heart failure is associated with reduced survival independent of glomerular filtration rate. Heart. 2010;96:1297–1302. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.194878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Damman K, van Veldhuisen DJ, Navis G, Voors AA, Hillege HL. Urinary neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin (NGAL), a marker of tubular damage, is increased in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:997–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singer E, Elger A, Elitok S, Kettritz R, Nickolas TL, Barasch J, Luft FC, Schmidt-Ott KM. Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin distinguishes pre-renal from intrinsic renal failure and predicts outcomes. Kidney Int. 2011;80:405–414. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forman DE, Butler J, Wang Y, Abraham WT, O'Connor CM, Gottlieb SS, Loh E, Massie BM, Rich MW, Stevenson LW, Young JB, Krumholz HM. Incidence, predictors at admission, and impact of worsening renal function among patients hospitalized with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Palevsky P. Acute renal failure—definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Crit Care. 2004;8:R204–R212. doi: 10.1186/cc2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jungbauer CG, Birner C, Jung B, Buchner S, Lubnow M, von Bary C, Endemann D, Banas B, Mack M, Böger CA, Riegger G, Luchner A. Kidney injury molecule-1 and N-acetyl-beta-d-glucosaminidase in chronic heart failure: possible biomarkers of cardiorenal syndrome. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:1104–1110. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt-Ott KM, Mori K, Kalandadze A, Li JY, Paragas N, Nicholas T, Devarajan P, Barasch J. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin-mediated iron traffic in kidney epithelia. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2006;15:442–449. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000232886.81142.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garvin JL, Ortiz PA. The role of reactive oxygen species in the regulation of tubular function. Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;179:225–232. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-6772.2003.01203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Juncos R, Garvin JL. Superoxide enhances Na–K–2Cl cotransporter activity in the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F982–F987. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00348.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maisel AS, Mueller C, Fitzgerald R, Brikhan R, Hiestand BC, Iqbal N, Clopton P, van Veldhuisen DJ. Prognostic utility of plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in patients with acute heart failure: The NGAL EvaLuation Along with B-type NaTriuretic Peptide in acutely decompensated heart failure (GALLANT) trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:846–851. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epstein FH, Prasad P. Effects of furosemide on medullary oxygenation in younger and older subjects. Kidney Int. 2000;57:2080–2083. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Damman K, Ng Kam Chuen MJ, MacFadyen RJ, Lip GY, Gaze D, Collinson PO, Hillege HL, van Oeveren W, Voors AA, van Veldhuisen DJ. Volume status and diuretic therapy in systolic heart failure and the detection of early abnormalities in renal and tubular function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:2233–2241. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Francis GS, Benedict C, Johnstone DE, Kirlin PC, Nicklas J, Liang CS, Kubo SH, Rudin-Toretsky E, Yusuf S. Comparison of neuroendocrine activation in patients with left ventricular dysfunction with and without congestive heart failure. A substudy of the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) Circulation. 1990;82:1724–1729. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.5.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Francis GS, Siegel RM, Goldsmith SR, Olivari MT, Levine TB, Cohn JN. Acute vasoconstrictor response to intravenous furosemide in patients with chronic congestive heart failure. Activation of the neurohumoral axis. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:1–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Testani JM, Cappola TP, Brensinger CM, Shannon RP, Kimmel SE. Interaction between loop diuretic-associated mortality and blood urea nitrogen concentration in chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosen S, Stillman IE. Acute tubular necrosis is a syndrome of physiologic and pathologic dissociation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:871–875. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007080913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]