Abstract

In human liver, the two-electron reduction of quinone compounds such as menadione is catalyzed by cytosolic carbonyl reductase (CBR) and NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase (NQO1) activities. We assessed the relative contributions of CBR and NQO1 activities to the total menadione reducing capacity in liver cytosols from black (n = 31) and white donors (n = 63). Maximal menadione reductase activities did not differ between black (13.0 ± 5.0 nmol/min.mg), and white donors (11.4 ± 6.6 nmol/min.mg; p = 0.208). In addition, both groups presented similar levels of CBR activities (CBRblacks = 10.9 ± 4.1 nmol/min.mg versus CBRwhites = 10.5 ± 5.8 nmol/min.mg; p = 0.708). In contrast, blacks showed higher NQO1 activities (two-fold) than whites (NQO1blacks = 2.1 ± 3.0 nmol/min.mg versus NQO1whites =0.9 ± 1.6 nmol/min.mg, p < 0.01). To further explore this disparity, we tested whether NQO1 activity was associated with the common NQO1*2 genetic polymorphism by using paired DNA samples for genotyping. Cytosolic NQO1 activities differed significantly by NQO1 genotype status in whites (NQO1whites[NQO1*1/*1] = 1.3 ± 1.7 nmol/min.mg versus NQO1whites[NQO1*1/*2 + NQO1*2/*2] = 0.5 ± 0.7 nmol/min.mg, p < 0.01), but not in blacks (NQO1blacks[NQO1*1/*1] = 2.6 ± 3.4 nmol/min.mg versus NQO1blacks[NQO1*1/*2] = 1.1 ± 1.2 nmol/min.mg, p = 0.134). Our findings pinpoint the presence of significant interethnic differences in polymorphic hepatic NQO1 activity.

Keywords: Carbonyl reductase, NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase, Ethnicity, Genotype, Liver, Menadione, Quinones

1. Introduction

Hepatic cytosolic carbonyl reductase (CBR) and NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase (NQO1) catalyze the reduction by two-electron transfer of a wide range of quinone compounds using NADP(H) as cofactor. The resulting hydroquinone derivatives are rapidly converted to glucuronyl or sulfate conjugates which prevents subsequent reoxidation to quinones (Lind et al., 1982). Thus, the formation of hydroquinones is considered a detoxification step because of the many deleterious effects of the parent quinones. For example, quinone compounds can generate reactive oxygen species through reactions of redox cycling in aerobic conditions.

In human liver, the prototypical quinone substrate menadione (vitamin K3) is reduced to menadiol by CBR and NQO1 cytosolic activities (Riley and Workman, 1992; Forrest and Gonzalez, 2000). A prominent feature of NQO1 is its sensitivity to inhibition by the anticoagulant dicoumarol in the micromolar range. Dicoumarol is a specific competitive inhibitor that competes with the NADP(H) cofactor for binding to NQO1 (Hosoda et al., 1974; Asher et al., 2004). On the other hand, biochemical studies on human CBR showed that cytosolic CBR activity is not inhibited by dicoumarol concentrations in the micromolar range (Wermuth, 1981; Wermuth et al., 1986; Rosemond and Walsh, 2004).

The relative contributions of CBR and NQO1 activities to the total quinone reducing capacity was estimated by Wermuth et al. in a set of eight human livers. The authors concluded that hepatic CBR accounted for the bulk (55–70%) of the total quinone reductase activity (Wermuth et al., 1986; Ross and Siegel, 2004). In support of this observation, low levels of NQO1 protein were detected by immunoblot analysis of five liver cytosolic samples (Siegel and Ross, 2000). To the best of our knowledge, the range of interindividual variability and the relative contributions of hepatic CBR and NQO1 cytosolic activities have not been evaluated in groups with relatively robust sample sizes. This is somewhat surprising given the prominent role of CBR and NQO1 during the biotransformation of several drug substrates and environmental toxins (Rosemond and Walsh, 2004). In addition, it is also now recognized that in some cases, the ethnic background of an individual may be a useful surrogate to assist during the identification of environmental and/or genetic factors potentially associated with distinctive phenotypic traits. There are many relevant examples of substantial disparities in the metabolism of xenobiotics among individuals with different ethnic background (Burchard et al., 2003; Evans and Relling, 2004; Daar and Singer, 2005). In consequence, our first aim was to evaluate the extent of interindividual variability on CBR and NQO1 activities in samples from black and white subjects. Therefore, we measured CBR and NQO1 activities in liver cytosolic fractions from black (n = 31) and white (n = 63) liver donors by using the substrate menadione and the specific NQO1 inhibitor dicoumarol.

There is a well-characterized genetic polymorphism in NQO1 (NQO1*2, rs1800566) that results in a proline-to-serine change at position 187 in the aminoacid chain of NQO1. The resulting NQO1 protein variant (NQO1S187) is rapidly degraded by the ubiquitin proteasomal system. Protein turnover studies by Siegel et al. demonstrated that the half-life of variant NQO1S187 was approximately 1.2 h, whereas the half life of wild type NQO1 (NQO1P187) was more than 18 h (Siegel et al., 2001). The distribution of the NQO1*2 polymorphism has been characterized in different ethnic groups. The variant NQO1*2 allele is relatively common among North American blacks and whites, and the allele frequencies are similar in both ethnic groups (q = 0.19 for blacks, and q = 0.16 – 0.20 for whites) (Gaedigk et al., 1998; Blanco et al., 2002). The phenotypic effect of the NQO1*2 polymorphism has been characterized in some normal human tissues, tumors and cell lines (Ross et al., 1994; Siegel et al., 1999; Ross and Siegel, 2004). For example, NQO1 activity was significantly lower in peritoneal tumor samples from subjects with heterozygous NQO1*1/*2 genotypes than in those tumors from patients with homozygous NQO1*1/*1 genotype (Fleming et al., 2002). Interestingly, the impact of the NQO1*2 polymorphism on hepatic NQO1 activity has not been reported. Therefore, our second aim was to investigate whether the common NQO1*2 genetic polymorphism impacts on cytosolic NQO1 activities by using paired DNA samples for genotype analysis. Together, our findings provide the necessary platform to further evaluate the impact of polymorphic NQO1 on the metabolism of different xenobiotic substrates, and document a previously unrecognized difference in the levels of hepatic NQO1 activities between blacks and whites.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Human liver cytosols and DNA samples

The Institutional Review Board of the State University of New York at Buffalo approved this research. Information on the donors’ ethnicity assumed that subjects fall into discrete ethnic categories (black or white). In most cases, no information was available regarding the exact geographical origin of the donors, and no information was available on the ethnicity of the donor’s parents. Human liver tissue from black (n = 31) and white donors (n = 63) was processed at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, and was provided by the Liver Tissue Procurement and Distribution System (NIH Contract #N01-DK-9-2310), and by the Cooperative Human Tissue Network, respectively. Liver tissue samples were processed following standardized procedures to obtain cytosolic fractions and DNA.

2.2 Menadione reductase, CBR and NQO1 activities in liver cytosols

Maximal cytosolic menadione reductase activities were measured by recording the rate of oxidation of the NADP(H) cofactor at 340 nm using menadione (200 μM) as substrate (NADP(H) molar absorption coefficient, 6220 M−1cm−1) (Wermuth, 1981). Maximal CBR and NQO1 cytosolic activities were determined by using the specific NQO1 inhibitor dicoumarol (5 μM) in the presence of the substrate menadione and the NADP(H) cofactor. CBR activity was estimated as the fraction of total menadione reductase activity that is not inhibited by dicoumarol (NQO1) (Benson et al., 1980; Wermuth et al., 1986). Different dicoumarol concentrations (range: 1 – 20 μM) were tested for NQO1 inhibition in the presence of 200 μM menadione by using pooled cytosols and individual samples, respectively. Consistent with previous reports, maximal and reproducible NQO1 inhibition was achieved with 5 μM dicoumarol (Wermuth et al., 1986; Preusch et al., 1991; Bello et al., 2004). For further validation, reverse inhibition experiments were performed on a fraction of the samples by using the specific CBR inhibitor rutin (150 μM), menadione and NADP(H) (Wermuth et al., 1986; Forrest and Gonzalez, 2000). The analysis in parallel of 30 cytosols (15 backs, 15 whites) showed that comparable levels of CBR and NQO1 activities were obtained with either rutin (CBR inhibitor) or dicoumarol (NQO1 inhibitor).

Measurements for each sample were performed in duplicate using a Cary Varian Bio 300 UV-visible spectrophotometer equipped with thermal control and proprietary software for enzyme kinetic data analysis. Experiments were performed to determine conditions that ensure maximal velocities and linear relationships with respect to incubation times and cytosolic protein concentrations. The intraday CV for maximal menadione reductase activity was 1.4% (n = 10 determinations), and the inter-day CV was 2.2% (n = 15 determinations), respectively. The lower limit of detection was 0.1 nmol/min.mg.

Typical incubation mixtures (final volume: 1.0 ml) contained potassium phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4), 200 μM NADP(H) (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 200 μM menadione (Sigma Aldrich), and 5 μM dicoumarol (if applicable). Complete mixtures were equilibrated for 2 min at 37°C after the addition of cytosols. The rates of NADP(H) oxidation were recorded for 4 min at an acquisition speed of 10 readings/s (2400 readings). Enzymatic velocities were automatically calculated by linear regression of the ΔAbs/Δtime points and expressed as nmol/min.mg. Regression coefficients r ≥ 0.95 were obtained for all enzymatic measurements. Cytosolic protein concentrations were determined with an assay based on Bradford’s technique using bovine serum albumin as standard (BioRad Assay, Hercules, CA).

2.3 NQO1 genotyping

The NQO1*2 polymorphism (rs1800566) was examined by PCR-RFLP analysis as described (Wiemels et al., 1999; Blanco et al., 2002). Briefly, Each 50-μl PCR contained 20 ng of genomic DNA, nuclease-free water, 50 pmol of each primer (forward: 5′-CCTCTCTGTGCTTTCTGTATCC-3′, and reverse: 5′-GATGGACTTGCCCAAGTGATG-3′), 2.5 units of Amplitaq Gold DNA polymerase (Perkin–Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Boston, MA), 250 μM each dNTP (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and Gene Amp PCR buffer (Perkin–Elmer). PCR amplifications were performed in a MJ Research PTC 200 Thermal cycler. PCR products (299 bp) were digested with Hinf I (Invitrogen) and analyzed by electrophoretic separation on 3% agarose gels (BioWhittaker, Rockland, ME). Samples with homozygous NQO1*1/*1 (C/C) genotypes presented two bands (85 bp and 214 bp), heterozygous NQO1*1/*2 (C/T) samples presented four bands (63 bp, 85 bp, 151 bp, and 214 bp) and homozygous NQO1*2/*2 (T/T) samples presented three bands (63 bp, 85 bp, and 151 bp), respectively. Adequate negative and positive controls were included in all PCR runs. Randomly selected PCR products were sequenced with both forward and reverse PCR primers for quality control. The resultant trace files were assembled and analyzed using the public SNP server at the National Cancer Institute (http://lpgws.nci.nih.gov/perl/snp/snp_cgi.pl). Perfect concordance was observed between NQO1 genotypes determined by PCR-RFLP and direct sequencing, respectively.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Values from cytosolic enzymatic activities were used to compute descriptive statistics for each group (e.g. means, standard deviations, ranges and percentiles). Cytosolic enzymatic activities from each group were used to generate histograms and Q-Q plots to evaluate normal frequency distributions. Unpaired Student’s t tests were used to compare population means of data sets normally distributed. The Mann-Whitney test was used to compare population means of data sets with non-normal distributions and relatively small sample sizes (n ≤ 20). The Mann-Whitney test with normal approximation for large data sets was used to compare population means of data sets with non-normal distributions and sample sizes with n ≥ 20 (Zar, 1984; Glantz, 1993; Jones, 2002). In all cases, differences were considered to be significant at p < 0.05. Computations were performed with Microsoft Excel 2000 version 9.0 (Microsoft), SYSTAT II version 11.00.01, and GraphPad Prism version 4.03 (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA).

3. Results

3.1 Menadione reductase, CBR and NQO1 activities in liver cytosols from black and white donors

First, we sought to evaluate maximal menadione reductase activities in liver cytosolic fractions from blacks (n = 31) and whites (n = 63). Demographic, and additional relevant information on the donor history is listed in table 1. Extensive literature searches showed that none of the drugs listed are known inducers of human CBR and NQO1 activities. Both groups of donors were comparable in terms of age (meanwhites = 46 years, meanblacks = 34 years), and sex (maleswhites = 64%, femaleswhites = 36%, and malesblacks = 58%, femalesblacks = 42%). There was substantial variability in menadione reductase activities within each group. The largest range of menadione reductase activity was found among whites (range: <0.1 nmol/min.mg – 29.0 nmol/min.mg) as compared to blacks (range: 4.2 – 24.7 nmol/min.mg). Statistical comparisons demonstrated that cytosolic menadione reductase activities were similar between black and white donors (blacks = 13.0 ± 5.0 nmol/min.mg versus whites = 11.4 ± 6.6 nmol/min.mg; Student’s t test, p = 0.208. Figure 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of liver donors

| Sample | ID | Sex | Ethnicity | Age | Patient Diseasea | Liver Disease | Smoker | Drugb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | M | B | 2 | Normal | Normal | No | Ddavp |

| 2 | 35 | F | B | 1 | Biliary Atresia | Cirrhotic | No | Unknown |

| 3 | 151 | M | B | 32 | Normal | Normal | Unknown | Unknown |

| 4 | 177 | M | B | 39 | Normal | Normal | No | Ddavp |

| 5 | 202 | F | B | 5 | Normal | Normal | Unknown | Unknown |

| 6 | 216 | M | B | 20 | Normal | Normal | Yes | Dopamine |

| 7 | 237 | M | B | 23 | Normal | Normal | No | Unknown |

| 8 | 245 | M | B | 19 | Normal | Normal | No | Dopamine |

| 9 | 247 | M | B | 46 | Normal | Normal | No | Dopamine |

| 10 | 248 | M | B | 41 | Normal | Normal | No | Dex/HC |

| 11 | 253 | F | B | 45 | Normal | Normal | No | Dex/HC |

| 12 | 359 | M | B | 6 | Normal | Normal | No | Dopamine |

| 13 | 362 | F | B | 41 | Cardiovascular | Normal | No | Cimetidine/H2 blocker |

| 14 | 435 | F | B | 58 | Cardiovascular | Normal | No | None |

| 15 | 480 | F | B | 51 | Epilepsy | Normal | Yes | Ddavp |

| 16 | 492 | F | B | 63 | Diabetes | Normal | No | Dopamine |

| 17 | 836 | F | B | 53 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| 18 | 850 | F | B | 44 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| 19 | 847 | M | B | 59 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| 20 | 159 | F | B | 7 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| 21 | 844 | M | B | 68 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| 22 | 38 | F | W | 64 | Cancer -NS- | Nl adj tissue | Unknown | Unknown |

| 23 | 122 | M | W | 67 | Colorectal Cancer | Nl adj tissue | Unknown | Unknown |

| 24 | 152 | F | W | 40 | Normal | Normal | Unknown | Unknown |

| 25 | 162 | M | W | 18 | Normal | Normal | Unknown | Ddavp |

| 26 | 174 | F | W | 23 | Normal | Normal | Yes | Dex/HC |

| 27 | 175 | M | W | 32 | Normal | Normal | No | Thyroid |

| 28 | 218 | M | W | 19 | Normal | Normal | No | Ddavp |

| 29 | 318 | F | W | 2 | Normal | Normal | No | Barb/toin |

| 30 | 320 | M | W | 25 | Normal | Normal | Yes | Cimetidine/H2 blocker |

| 31 | 329 | M | W | 32 | Unknown | Necrosis | No | Unknown |

| 32 | 331 | F | W | 62 | Normal | Normal | Yes | Dopamine |

| 33 | 334 | M | W | 63 | Normal | Normal | No | Dopamine |

| 34 | 335 | M | W | 36 | Normal | Normal | Yes | Barb/toin |

| 35 | 340 | M | W | 52 | Normal | Normal | No | Dopamine |

| 36 | 346 | M | W | 24 | Normal | Normal | No | Unlikely prob |

| 37 | 347 | F | W | 4 | Normal | Normal | No | Cimetidine/H2 blocker |

| 38 | 348 | M | W | 43 | Normal | Normal | No | Dopamine |

| 39 | 351 | M | W | 49 | Normal | Normal | Yes | Dopamine |

| 40 | 353 | F | W | 68 | Normal | Normal | No | Dex/HC |

| 41 | 356 | M | W | 37 | Normal | Normal | Yes | Dopamine |

| 42 | 378 | M | W | 81 | Normal | Normal | No | Dex/HC |

| 43 | 390 | F | W | 59 | Unknown | Normal | No | Unknown |

| 44 | 394 | F | W | 52 | Unknown | Unknown | No | Unknown |

| 45 | 395 | F | W | 57 | Unknown | Unknown | No | Unknown |

| 46 | 397 | M | W | 52 | Unknown | Unknown | No | Unknown |

| 47 | 411 | M | W | 30 | Normal | Normal | No | Unknown |

| 48 | 430 | M | W | 66 | Normal | Normal | No | Unknown |

| 49 | 431 | M | W | 56 | Unknown | Normal | No | Unknown |

| 50 | 433 | M | W | 46 | Cancer -NS- | Normal | Yes | Thyroid |

| 51 | 434 | M | W | 64 | Normal | Normal | Yes | Dex/HC |

| 52 | 436 | F | W | 49 | Psychiatric | Normal | No | Barb/toin |

| 53 | 439 | M | W | 48 | Normal | Normal | No | Thyroid |

| 54 | 465 | F | W | 61 | Normal | Normal | No | Ethanol |

| 55 | 466 | M | W | 20 | Normal | Normal | Yes | Dopamine |

| 56 | 469 | M | W | 28 | Normal | Normal | No | Dex/HC |

| 57 | 470 | F | W | 68 | Cardiovascular | Normal | Yes | Ddavp |

| 58 | 475 | F | W | 70 | Normal | Normal | No | Dopamine |

| 59 | 476 | F | W | 66 | Cardiovascular | Normal | Yes | Statin |

| 60 | 477 | F | W | 38 | Normal | Normal | No | Barb/toin |

| 61 | 478 | F | W | 56 | Normal | Normal | Yes | Thyroid |

| 62 | 482 | M | W | 78 | Cardiovascular | Fibrotic | No | Dex/HC |

| 63 | 483 | M | W | 62 | Unknown | Normal | No | Unknown |

| 64 | 484 | F | W | 34 | Normal | Normal | Yes | Thyroid |

| 65 | 491 | F | W | 22 | Normal | Normal | Yes | Dex/HC |

| 66 | 856 | M | W | 67 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| 67 | 849 | F | W | 46 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| 68 | 865 | M | W | 34 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| 69 | 837 | F | W | 40 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| 70 | 161 | M | B | 41 | Cancer -NS- | Cancer -NS- | Unknown | Unknown |

| 71 | 440 | M | B | 29 | Normal | Normal | No | None |

| 72 | 445 | M | B | 46 | Normal | Normal | Yes | Dex/HC, Erythro, Barb/toin, Ddavp, Ethanol |

| 73 | 458 | F | B | 27 | Unknown | Normal | Unknown | Unknown |

| 74 | 479 | F | B | 57 | Cardiovascular | Normal | Yes | Erythro |

| 75 | 620 | M | B | 43 | Normal | Normal | Yes | Dopamine |

| 76 | 624 | M | B | 23 | Normal | Normal | Yes | Dopamine, Cimetidine, Erythro, Dex/H, Ddavp |

| 77 | 635 | F | B | 41 | Normal | Normal | No | Unknown |

| 78 | 659 | M | B | 52 | Normal | Normal | No | Thyroid, Dex/HC, Ethanol, Dopamine |

| 79 | 811 | M | B | 20 | Normal | Normal | No | Unknown |

| 80 | 322 | M | W | 3 | Other | Necrosis | No | Dex/HC, Thyroid, Midazolam |

| 81 | 323 | M | W | 43 | Cancer -NS- | Normal | No | Dex/HC |

| 82 | 328 | M | W | 50 | Normal | Normal | Yes | Dex/HC, Cimetidine, Dopamine, Ddavp |

| 83 | 343 | M | W | 35 | Normal | Normal | No | Ddavp, Dopamine, Ethanol, Dex/HC |

| 84 | 350 | F | W | 75 | Cardiovascular | Normal | No | Dex/HC, Dopamine, Ddavp |

| 85 | 355 | M | W | 40 | Normal | Normal | No | Unknown |

| 86 | 365 | M | W | 28 | Normal | Normal | Yes | Dex/HC, Dopamine |

| 87 | 369 | F | W | 66 | Cardiovascular | Normal | Yes | Sex steroid, Thyroid, Ddavp, Dopamine, Ethanol |

| 88 | 370 | M | W | 45 | Diabetes | Normal | Yes | Dex/HC, Dopamine |

| 89 | 372 | M | W | 37 | Unknown | Normal | Yes | Ethanol |

| 90 | 373 | M | W | 28 | Normal | Normal | Yes | Dex/HC, Dopamine |

| 91 | 374 | M | W | 72 | Cardiovascular | Normal | No | Unknown |

| 92 | 376 | M | W | 47 | Normal | Normal | Yes | Dopamine |

| 93 | 377 | M | W | 75 | Diabetes | Normal | No | Dopamine |

| 94 | 379 | M | W | 34 | Normal | Normal | No | Cimetidine, Ddavp, Dopamine, Dex/HC |

Cancer -NS-: not specified

Dex: dexamethasone; HC: hydrocortisone; Ddavp: vasopressin

Figure 1.

Maximal menadione reductase activities in liver cytosols from blacks and whites. The lower and upper boundaries of each box define the 25th and 75th percentile, respectively. The whiskers indicate the lowest and the highest value. The thin line inside each box indicates the median, and the bold line shows the population mean. Differences between the means from both groups were assessed by the Student’s t test.

We used the specific NQO1 inhibitor dicoumarol in the presence of menadione to evaluate the relative contributions of cytosolic CBR and NQO1 activities in black and white donors. Correlation analyses showed no significant associations between NQO1 and CBR activities in samples from whites (Pearson’s correlation coefficient, r = 0.07) and blacks (Pearson’s correlation coefficient, r = 0.0005), respectively. The levels of expression of some drug-metabolizing enzymes experience marked changes during development in infants and children (Kearns et al., 2003). In this study, a small number of samples were obtained from pediatric donors (<12 yr of age; n = 3 whites, and n = 5 blacks). Exploratory analyses showed no significant differences in the levels of menadione reductase, CBR and NQO1 activities when pediatric versus non-pediatric donors were compared in samples from whites and blacks, respectively (data not shown). Smoking status (yes/no) was available for a subset of 77 samples (82%). Statistical comparisons showed no significant differences in cytosolic menadione reductase, CBR and NQO1 activities when smokers versus non-smokers were compared in samples from both ethnic groups (data not shown).

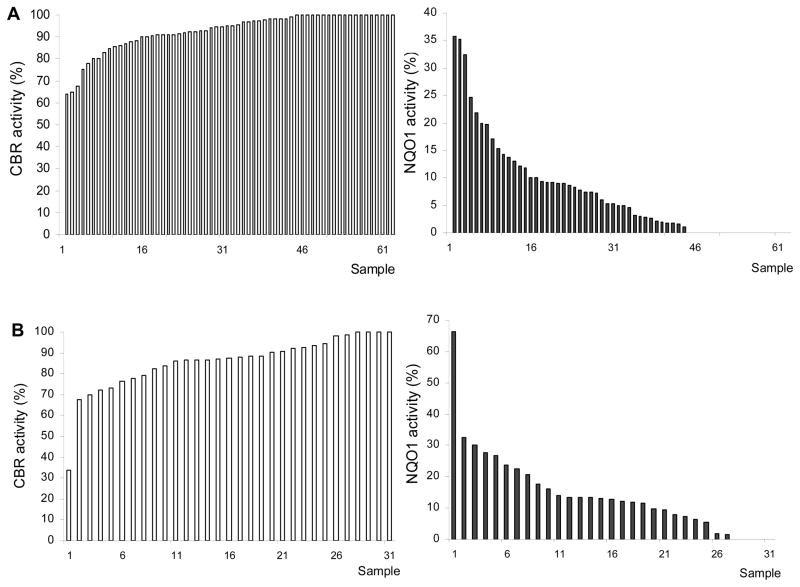

We observed variable levels of CBR activities in whites (range: <0.1 – 28.0 nmol/min.mg), and blacks (range: 4.1 – 21.5 nmol/min.mg). Statistical comparisons showed that maximal CBR activities from blacks and whites did not differ significantly (CBRblacks = 10.9 ± 4.1 nmol/min.mg versus CBRwhites = 10.5 ± 5.8 nmol/min.mg; Student’s t test, p = 0.708. Figure 2, panel A). In contrast, blacks presented significantly higher NQO1 activities than whites (NQO1blacks = 2.1 ± 3.0 nmol/min.mg versus NQO1whites = 0.9 ± 1.6 nmol/min.mg; Mann-Whitney with normal approximation, p < 0.01 Figure 2, panel B). The percentages of samples with non-detectable NQO1 activity (<0.1 nmol/min.mg) were 33% (whites) and 13% (blacks). On average, NQO1 activity accounted for 15% and 7% of the total cytosolic menadione reductase activity in blacks and whites, respectively. However, the relative contributions of NQO1 activity differed widely among individuals. For example, NQO1 activity accounted for up to 66% of the total menadione reductase activity in one sample. The ranges of NQO1 relative contributions were <0.1 – 32% for whites, and <0.1 – 66% for blacks (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

CBR (panel A) and NQO1 (panel B) activities in liver cytosols from whites and blacks. Bold lines indicate the mean of each group. Differences between the means were assessed by the Student’s t test (panel A), and by the Mann-Whitney test with normal approximation (panel B).

Figure 3.

Relative contributions of cytosolic CBR and NQO1 activities in white (panel A), and black (panel B) liver donors. Relative CBR and NQO1 contributions to the total menadione reducing capacity are expressed as percent fractions (%).

3.2 NQO1 phenotype-genotype associations in black and white donors

We analyzed NQO1*2 genotype distributions in both groups by using paired DNA samples to further explore the basis of variable hepatic NQO1 activity. Siegel et al. showed that subjects with the homozygous NQO1*2/*2 genotype had no detectable NQO1 protein in saliva, while subjects with heterozygous NQO1*1/*2 genotype had lower levels of NQO1 as compared to individuals with homozygous NQO1*1/*1 genotype (Siegel et al., 1999). In addition, studies with cell culture models and tumor samples described correlations between NQO1*2 genotype status and NQO1 enzymatic activity (Traver et al., 1997; Fleming et al., 2002; Ross and Siegel, 2004). Thus, we compared NQO1 cytosolic activities after stratifying by NQO1 genotype. Allele frequencies were: p = 0.84, q = 0.16 for blacks, and p = 0.78, q = 0.22, for whites. In whites the genotype distribution was as follows: 59% were homozygous for the C allele, 38% were heterozygous C/T, and 3% were homozygous for the T allele. In blacks, 68% presented the homozygous C/C genotype, and 32% were heterozygous C/T. NQO1 genotype distributions were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in both groups (Chi square test; whites, p = 0.527, and blacks, p = 0.620). In blacks, statistical comparisons failed to show significant differences between cytosolic NQO1 activities in samples from donors with homozygous NQO1*1/*1 genotype as compared to samples from donors with heterozygous NQO1*1/*2 genotype (NQO1blacks[NQO1*1/*1] = 2.6 ± 3.4 nmol/min.mg versus NQO1blacks[NQO1*1/*2] = 1.1 ± 1.2 nmol/min.mg, Mann-Whitney test, p = 0.134. Figure 4, panel A). On the other hand, NQO1 activities differed significantly by NQO1 genotype status in the group of white donors (NQO1whites[NQO1*1/*1] = 1.3 ± 1.7 nmol/min.mg versus NQO1whites[NQO1*1/*2 + NQO1*2/*2] = 0.5 ± 0.7 nmol/min.mg, Mann-Whitney test with normal approximation, p < 0.01. Figure 4, panel B).

Figure 4.

Relationship between NQO1 phenotype and NQO1 genotypes in blacks (panel A), and whites (panel B). Bold lines indicate the mean of each group. Differences between the means were assessed by the Mann-Whitney test (panel A), and by the Mann-Whitney test with normal approximation (panel B).

4. Discussion

The two-electron reduction of carbonyl moieties is a crucial step in the metabolism of many quinone drugs and environmental toxins (Rosemond and Walsh, 2004). CBR and NQO1 are the main sources of cytosolic quinone reductase activity in human liver (Wermuth et al., 1986; Jarabak J. and Harvey R. G., 1993). However, there is a paucity of reports describing the contributions of CBR and NQO1 in relatively large groups of samples from individuals with different ethnic backgrounds. Therefore, the first aim of the present study was to determine the relative contributions of CBR and NQO1 activities in liver cytosols from black and white donors using the prototypical quinone substrate menadione and the specific NQO1 inhibitor dicoumarol. Dicoumarol has been extensively used to investigate the consequences of lack of NQO1 function in studies on sub-cellular fractions and intact cells (Benson et al., 1980; Preusch et al., 1991; Ross et al., 2000; Fleming et al., 2002; Bello et al., 2004). Dicoumarol (range: 1 – 25 μM) did not inhibit the menadione reductase activity of recombinant human CBR1 in the presence of NADP(H) cofactor (Gonzalez Covarrubias and Blanco, unpublished observations).

Hepatic CBR activity accounted for the bulk of the total menadione reducing capacity in liver cytosols from whites (average = 93%), and blacks (average = 85%). CBR activity varied widely in samples from both ethnic groups. Interestingly, our data indicate that CBR activity does not differ in liver cytosols from black and white donors (Figure 2, panel A). CBR activity plays an important role in the metabolism of many clinically relevant drugs such as the anticancer anthracycline doxorubicin and the antipsychotic haloperidol (Someya et al., 1992; Kudo and Ishizaki, 1999; Forrest and Gonzalez, 2000). For example, hepatic CBR activity accounts for approximately 40% of the clearance of haloperidol by catalyzing the reduction of haloperidol (HP) to reduced haloperidol (RHP). Lam et al. reported similar plasma RHP/HP ratios in black (n = 39) and white (n = 66) schizophrenic patients (Lam et al., 1995). Thus, it is possible that similar RHP/HP plasma ratios may in part result from the comparable levels of hepatic CBR activities among blacks and whites.

Our study documents the presence of significant differences in hepatic cytosolic NQO1 activities from whites and blacks (Figure 2, panel B). On average, samples from blacks presented 2.3-fold higher NQO1 activity than samples from whites. It is possible that complex interplays between genetic and epigenetic factors relatively exclusive for a particular ethnic group may be contributing to the differences in levels of NQO1 cytosolic activities between blacks and whites. Kalinowski et al. reported higher levels of NAD(P)H-oxidase and endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) in endothelial cells from blacks as compared to cells isolated from white donors. In turn, endothelial cells from blacks generated significantly more superoxide (O2−), which may help to explain the differences in racial predisposition to the endothelium dysfunction during vascular distress (Kalinowski et al., 2004). The free radical superoxide contributes to oxidative stress, and it is dismuted to hydrogen peroxide, a much less harmful product, by the family of superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzymes. Recently, Zitouni et al. described higher SOD activities in diabetic black patients with African ancestry as compared to white patients from the UK (Zitouni et al., 2005). Our results appear to be in line with these observations because a major function of NQO1 is to decrease the formation of oxidative species, and variable NQO1 levels impact on the intracellular redox balance (Talalay and Dinkova-Kostova, 2004). Therefore, our findings on hepatic NQO1 activities may provide further support to the contemporary notion that redox cellular balance may operate differently between blacks and whites (Cardillo et al., 1999; Perregaux et al., 2000; Kalinowski et al., 2004).

We also detected a significant association between cytosolic NQO1 activities and NQO1 genotypes in liver samples from whites. The average NQO1 activity in the group of samples with homozygous NQO1*1/*1 genotype was 2.6-fold higher than the activity for the group with heterozygous NQO1*1/*2 plus homozygous NQO1*2/*2 genotypes, respectively. The fold difference in NQO1 activity after stratification by NQO1 genotype was similar in blacks (2.4-fold), but comparisons between genotype categories did not reach statistical significance. Therefore, additional research is needed to confirm the potential trend towards an NQO1 genotype-phenotype association in black donors. Together, our observations on human liver samples further extend and confirm the effect of NQO1*2 genotype with respect to NQO1 phenotype that has been reported for other human tissues (Traver et al., 1992; Siegel et al., 1999; Ross and Siegel, 2004). In consequence, further NQO1 genotype-phenotype association studies in human liver samples with different NQO1 substrates are warranted.

In conclusion, we pinpointed the presence of significant differences in the levels of cytosolic NQO1 activities from white and black liver donors. Therefore, it will be of paramount interest to investigate whether interethnic differences in hepatic NQO1 activities also exist for substrates of clinical and toxicological relevance such as the antitumor antibiotic mitomycin C and naturally occurring naphthoquinones (Munday, 2004; Talalay and Dinkova-Kostova, 2004).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/NIGMS grant R01GM73646-01 to JGB, NIH/NIGMS grant U01GM61393, and NIH/NIGMS Pharmacogenetics Research Network and Database grant U01GM61374, http://pharmgkb.org. The excellent assistance of Erick Vasquez is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Dr. Christine B. Ambrosone for helpful discussions during the preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Asher G, Lotem J, Sachs L, Shaul Y. p53-dependent apoptosis and NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1. Methods Enzymol. 2004;382:278–293. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)82016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello RI, Gomez-Diaz C, Navas P, Villalba JM. NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 expression, hydrogen peroxide levels, and growth phase in HeLa cells. Methods Enzymol. 2004;382:234–243. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)82013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson AM, Hunkeler MJ, Talalay P. Increase of NAD(P)H:quinone reductase by dietary antioxidants: possible role in protection against carcinogenesis and toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:5216–5220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.9.5216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco JG, Edick MJ, Hancock ML, Winick NJ, Dervieux T, Amylon MD, Bash RO, Behm FG, Camitta BM, Pui CH, Raimondi SC, Relling MV. Genetic polymorphisms in CYP3A5, CYP3A4 and NQO1 in children who developed therapy-related myeloid malignancies. Pharmacogenetics. 2002;12:605–611. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200211000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchard EG, Ziv E, Coyle N, Gomez SL, Tang H, Karter AJ, Mountain JL, Perez-Stable EJ, Sheppard D, Risch N. The Importance of Race and Ethnic Background in Biomedical Research and Clinical Practice. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1170–1175. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb025007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardillo C, Kilcoyne CM, Cannon RO, III, Panza JA. Attenuation of Cyclic Nucleotide–Mediated Smooth Muscle Relaxation in Blacks as a Cause of Racial Differences in Vasodilator Function. Circulation. 1999;99:90–95. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daar AS, Singer PA. Pharmacogenetics and geographical ancestry: implications fro drug development and global health. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:241–246. doi: 10.1038/nrg1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans WE, Relling MV. Moving towards individualized medicine with pharmacogenomics. Nature. 2004;429:464–468. doi: 10.1038/nature02626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming RA, Drees J, Loggie BW, Russell GB, Geisinger KR, Morris RT, Sachs D, McQuellon RP. Clinical significance of a NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 polymorphism in patients with disseminated peritoneal cancer receiving intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy with mitomycin C. Pharmacogenetics. 2002;12:31–37. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200201000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest GL, Gonzalez B. Carbonyl reductase. Chem Biol Interact. 2000;129:21–40. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(00)00196-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaedigk A, Tyndale RF, Jurima-Romet M, Sellers EM, Grant DM, Leeder JS. NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase: polymorphisms and allele frequencies in Caucasian, Chinese and Canadian Native Indian and Inuit populations. Pharmacogenetics. 1998;8:305–313. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199808000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glantz SA. Primer of Biostatistics. McGraw-Hill, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hosoda S, Nakamura W, Hayashi K. Properties and reaction mechanism of DT diaphorase from rat liver. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:6416–6423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarabak J, Harvey RG. Studies on Three Reductases Which Have Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Quinones as Substrates. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1993;303:394–401. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. Pharmaceutical Statistics. Pharmaceutical Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kalinowski L, Dobrucki IT, Malinski T. Race-Specific Differences in Endothelial Function: Predisposition of African Americans to Vascular Diseases. Circulation. 2004;109:2511–2517. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000129087.81352.7A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns GL, Abdel-Rahman SM, Alander SW, Blowey DL, Leeder JS, Kauffman RE. Developmental Pharmacology -- Drug Disposition, Action, and Therapy in Infants and Children. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1157–1167. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo S, Ishizaki T. Pharmacokinetics of haloperidol: an update. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;37:435–456. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199937060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam YW, Jann MW, Chang WH, Yu HS, Lin SK, Chen H, Davis CM. Intra- and interethnic variability in reduced haloperidol to haloperidol ratios. J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;35:128–136. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1995.tb05000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind C, Hochstein P, Ernster L. DT-diaphorase as a quinone reductase: a cellular control device against semiquinone and superoxide radical formation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1982;216:178–185. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(82)90202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munday R. Activation and detoxification of naphthoquinones by NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase. Methods Enzymol. 2004;382:364–380. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)82020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perregaux D, Chaudhuri A, Rao S, Airen A, Wilson M, Sung BH, Dandona P. Brachial Vascular Reactivity in Blacks. Hypertension. 2000;36:866–871. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.5.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preusch PC, Siegel D, Gibson NW, Ross D. A note on the inhibition of DT-diaphorase by dicoumarol. Free Radic Biol Med. 1991;11:77–80. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(91)90191-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley RJ, Workman P. DT-diaphorase and cancer chemotherapy. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;43:1657–1669. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90694-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosemond MJ, Walsh JS. Human carbonyl reduction pathways and a strategy for their study in vitro. Drug Metab Rev. 2004;36:335–361. doi: 10.1081/dmr-120034154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross D, Beall H, Traver RD, Siegel D, Phillips RM, Gibson NW. Bioactivation of quinones by DT-diaphorase, molecular, biochemical, and chemical studies. Oncol Res. 1994;6:493–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross D, Kepa JK, Winski SL, Beall HD, Anwar A, Siegel D. NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1): chemoprotection, bioactivation, gene regulation and genetic polymorphisms. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2000;129:77–97. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(00)00199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross D, Siegel D. NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1, DT-diaphorase), functions and pharmacogenetics. Methods Enzymol. 2004;382:115–144. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)82008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel D, Anwar A, Winski SL, Kepa JK, Zolman KL, Ross D. Rapid Polyubiquitination and Proteasomal Degradation of a Mutant Form of NAD(P)H:Quinone Oxidoreductase 1. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:263–268. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel D, McGuinness SM, Winski SL, Ross D. Genotype-phenotype relationships in studies of a polymorphism in NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1. Pharmacogenetics. 1999;9:113–121. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199902000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel D, Ross D. Immunodetection of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) in human tissues. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;29:246–253. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00310-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Someya T, Shibasaki M, Noguchi T, Takahashi S, Inaba T. Haloperidol metabolism in psychiatric patients: importance of glucuronidation and carbonyl reduction. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1992;12:169–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talalay P, Dinkova-Kostova AT. Role of nicotinamide quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) in protection against toxicity of electrophiles and reactive oxygen intermediates. Methods Enzymol. 2004;382:355–364. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)82019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traver RD, Horikoshi T, Danenberg KD, Stadlbauer TH, Danenberg PV, Ross D, Gibson NW. NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase gene expression in human colon carcinoma cells: characterization of a mutation which modulates DT-diaphorase activity and mitomycin sensitivity. Cancer Res. 1992;52:797–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traver RD, Siegel D, Beall HD, Phillips RM, Gibson NW, Franklin WA, Ross D. Characterization of a polymorphism in NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase (DT-diaphorase) Br J Cancer. 1997;75:69–75. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wermuth B. Purification and properties of an NADPH-dependent carbonyl reductase from human brain. Relationship to prostaglandin 9-ketoreductase and xenobiotic ketone reductase. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:1206–1213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wermuth B, Platts KL, Seidel A, Oesch F. Carbonyl reductase provides the enzymatic basis of quinone detoxication in man. Biochem Pharmacol. 1986;35:1277–1282. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(86)90271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiemels JL, Pagnamenta A, Taylor GM, Eden OB, Alexander FE, Greaves MF. A Lack of a Functional NAD(P)H:Quinone Oxidoreductase Allele Is Selectively Associated with Pediatric Leukemias That Have MLL Fusions. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4095–4099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zar JH. Biostatistical Analysis. Prentice Hall, Inc; N.J: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Zitouni K, Nourooz-Zadeh J, Harry D, Kerry SM, Betteridge DJ, Cappuccio FP, Earle KA. Race-Specific Differences in Antioxidant Enzyme Activity in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A potential association with the risk of developing nephropathy. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1698–1703. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.7.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]