Minority groups represent an important and growing segment of the population of the United States, which is projected to comprise 47% non-Hispanic whites, 29% Hispanics, 13% non-Hispanic blacks, and 9% Asians by 2050 (1).

Although asthma affects all ethnic groups, the burden from this disease is disproportionately shared by certain minority groups and the economically disadvantaged. The prevalence of childhood asthma among Puerto Ricans (19.2%) or non-Hispanic blacks (12.7%) is higher than among non-Hispanic whites (8%) or Mexican Americans (6.4%) (2). Ethnic disparities in asthma morbidity and mortality are even more pronounced (3). Asthma mortality rates in children and adults are nearly eightfold and threefold higher, respectively, in non-Hispanic blacks than in non-Hispanic whites.

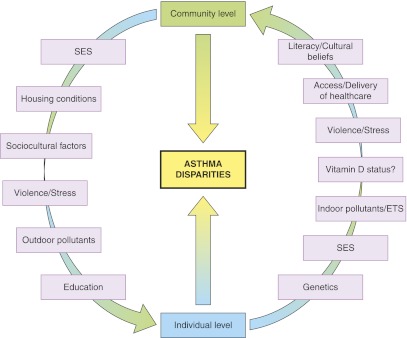

Ethnic and socioeconomic health disparities in asthma are the result of multiple factors operating at the individual and community levels (Figure 1). Poverty is both strongly correlated with ethnicity and a risk factor for asthma morbidity in the United States (4). Ethnicity is linked with racial ancestry and may affect asthma independently of poverty (e.g., through genetic variation); conversely, poverty can affect asthma independently of ethnicity (e.g., through access to healthcare). Very often, however, they have synergistic detrimental effects on asthma, influencing not only quality of care but also exposure to environmental and lifestyle (EL) risk factors.

Figure 1.

Known or potential determinants of asthma disparities. ETS = environmental tobacco smoke; SES = socioeconomic status.

Known or potential EL risk factors for disparities in asthma or asthma morbidity include cigarette smoking and environmental tobacco smoke (ETS), prematurity or low birth weight, allergen exposure, indoor and outdoor air pollution, diet, obesity, vitamin D insufficiency, viral respiratory infections (e.g., due to crowding), psychosocial stress, and poor adherence with prescribed treatment. We briefly discuss some of these factors below.

In the United States, cigarette smoking, ETS, and exposure to other indoor and outdoor pollutants vary widely by socioeconomic status (SES) and ethnicity. Current smoking in adults ranges from ∼7% in subjects with a graduate degree to ∼46% in those with a GED diploma (5), and from ∼30% in Puerto Ricans to ∼22% in Mexican Americans (6). Residents of economically deprived or inner-city communities are often exposed to allergens (e.g., cockroach) (7) and outdoor pollutants (e.g., diesel exhaust particles) associated with asthma morbidity (8).

Vitamin D insufficiency (a serum 25[OH]D <30 ng/ml) and asthma share common risk factors, including inner-city residence and African American ethnicity. Results from experimental and observational studies suggest that reduced maternal intake of vitamin D during pregnancy increases the risk of childhood asthma or wheezing, and that vitamin D insufficiency increases asthma morbidity in children and adults (9).

Inner-city residents and minority groups are often exposed to increased violence, and are thus more likely to experience psychosocial stress, which has been shown to increase asthma morbidity in adults and their children (10, 11). Depression and anxiety are more common in lower SES groups, and can lead to altered perception and report of symptoms. In turn, psychosocial stress could lead to decreased adherence with prescribed controller medications, independently or coupled with other factors (family or community structure and support, cultural beliefs, inadequate communication from or with healthcare providers, and reduced health literacy).

Results from recent studies suggest that racial ancestry influences ethnic disparities in asthma. African Americans and Puerto Ricans share both a significant proportion of African ancestry and a high burden from lung diseases such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (12). Whereas African ancestry has been associated with reduced FEV1 and FVC in African American adults without asthma (13) and Puerto Rican children (with and without asthma) (14), Native American ancestry has been associated with higher FEV1 and reduced risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults from New Mexico (15). These findings are intriguing and suggest that genetic or early-life EL factors correlated with racial ancestry partly explain asthma disparities. For example, discrepancies in asthma morbidity between Puerto Ricans and Mexican Americans (the “Hispanic paradox”) may be partly due to differences in African versus Native American ancestry. Results from recent genome-wide association studies suggest that certain asthma-susceptibility variants will be relevant to all ethnic groups, whereas others may have ethnic-specific effects (16).

What can we do about asthma disparities? The most important step would be to implement and enforce policies increasing access to healthcare for children and adults with asthma, regardless of their ethnicity or SES. However, increasing healthcare access is unlikely to suffice; additional steps must be taken to improve understanding of disease processes and therapeutic goals in patients with low literacy (17), ensure appropriate assessment of disease severity by physicians and patients (18), and increase prescription of and adherence with controller medications. For instance, parents of black and Hispanic children have lower expectations about asthma control and worse adherence with controller medications (partly due to concerns about medication dependency or side effects) than parents of non-Hispanic white children (19). In addition to trying to improve healthcare for all, new and ongoing policies should aim at the community level, such as improving asthma education and housing conditions, and reducing detrimental EL exposures (cigarette smoking, ETS, air pollution, allergens, inactivity, and unhealthy dietary patterns).

Observational and interventional research studies should try to identify and expand our understanding of risk factors for asthma disparities. Dissecting the genetic and EL factors underlying recently reported associations between racial ancestry and lung function or asthma is important and could help identify subpopulations at highest risk, reveal gene-by-gene and gene-by-environment interactions, and ultimately help develop new means to disease prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. In this context, it is important to include well-characterized minority populations in studies of genetics and epigenetics. Such studies should categorize subjects into appropriate subgroups (e.g., Puerto Rican, Filipino) instead of broad clusters (such as Hispanic or Asian) and objectively assess ancestry (e.g., by using genetic markers). Similarly, future studies should aim to refine characterization of SES and EL exposures at the individual and community levels, while also establishing long-term relationships with the communities under study.

Current financial realities dictate that cost-effective interventions to reduce asthma disparities should have the highest priority. Given available evidence, minorities and inner-city residents (who are at highest risk for vitamin D insufficiency) should be included in future clinical trials of vitamin D supplementation and asthma. Because of the multifactorial nature of such disparities, certain single-factor interventions (e.g., reduction of a single allergen) are likely to have a minor impact while generating major expenses. Multifaceted individual-, family-, or community-based interventions aimed at multiple risk factors (e.g., reducing ETS, increasing exercise and asthma education, and improving dietary practices) should be rigorously examined, as they may be more successful and cost-effective (20). Interventions aimed at physicians or healthcare organizations treating minority or economically disadvantaged groups (e.g. increasing cultural competency, changing prescription patterns, and improving communication) may have significant impact on asthma disparities (21, 22), but only limited data are available and thus further research is needed.

This is both an exciting and a challenging time for those interested in reducing unacceptable disparities in asthma. Concerned healthcare professionals and their professional societies must vigorously advocate for universal access to high-quality care for patients with asthma, as this would have a major impact on reducing existing disparities in disease morbidity. In parallel with these efforts, pragmatic and multifaceted measures to improve asthma care should be coupled with research studies targeting not only identification of risk factors but also the development of cost-effective interventions at the individual and community levels.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by grant HL079966 from the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Passel JS, Cohn D. U.S. population projections: 2005-2050. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2012.

- 2.Moorman JE, Rudd RA, Johnson CA, King M, Minor P, Bailey C, Scalia MR, Akinbami LJ. National surveillance for asthma—United States, 1980–2004. MMWR Surveill Summ 2007;56:18–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leong AB, Ramsey CD, Celedón JC. The challenge of asthma in minority populations. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol (In press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forno E, Celedón JC. Asthma and ethnic minorities: socioeconomic status and beyond. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;9:154–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC Cigarette smoking among adults, United States 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2007;56:1157–1161 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Prevalence of cigarette use among 14 racial/ethnic populations—United States, 1999-2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004;53:49–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salo PM, Arbes SJ, Crockett PW, Thorne PS, Cohn RD, Zeldin DC. Exposure to multiple indoor allergens in US homes and its relationship to asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;121:678–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Connor GT, Neas L, Vaughn B, Kattan M, Mitchell H, Crain EF, Evans R, III, Gruchalla R, Morgan W, Stout J, Adams GK, Lippmann M. Acute respiratory health effects of air pollution on children with asthma in US inner cities. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;121:1133–1139e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paul G, Brehm JM, Alcorn JF, Holguin F, Aujla SJ, Celedón JC. Vitamin D and asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185:124–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kozyrskyj AL, Mai X, McGrath P, HayGlass KT, Becker B, MacNeil B. Continued exposure to maternal distress in early life is associated with an increased risk of childhood asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177:142–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen RT, Canino GJ, Bird HR, Celedón JC. Violence, abuse, and asthma in Puerto Rican children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;178:453–459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han MK, Curran-Everett D, Dransfield MT, Criner GJ, Zhang L, Murphy JR, Hansel NN, DeMeo DL, Hanania NA, Regan EA, et al. COPDGene investigators: racial differences in quality of life in patients with COPD. Chest 2011;140:1169–1176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar R, Seibold MA, Aldrich MC, Williams LK, Reiner AP, Colangelo L, Galanter J, Gignoux C, Hu D, Sen S, et al. Genetic ancestry in lung-function predictions. N Engl J Med 2010;363:321–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brehm JM, Acosta-Perez E, Klei L, Roeder K, Barmada M, Boutaoui N, Forno E, Cloutier M, Datta S, Kelly R, et al. African ancestry and lung function in Puerto Rican children. J Allergy Clin Immunol (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruse S, Sood A, Petersen H, Liu Y, Leng S, Celedon JC, Gilliland F, Celli B, Belinsky SA, Tesfaigzi Y. New Mexican Hispanic smokers have lower odds of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and less decline in lung function than non-Hispanic whites. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;184:1254–1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torgerson DG, Ampleford EJ, Chiu GY, Gauderman WJ, Gignoux CR, Graves PE, Himes BE, Levin AM, Mathias RA, Hancock DB, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of asthma in ethnically diverse North American populations. Nat Genet 2011;43:887–892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosas-Salazar C, Apter AJ, Canino G, Celedón JC. Health literacy and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;129:935–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fritz GK, McQuaid EL, Kopel SJ, Seifer R, Klein RB, Mitchell DK, Esteban CA, Rodriguez-Santana J, Colon A, Alvarez M, et al. Ethnic differences in perception of lung function: a factor in pediatric asthma disparities? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;182:12–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu AC, Smith L, Bokhour B, Hohman KH, Lieu TA. Racial/ethnic variation in parent perceptions of asthma. Ambul Pediatr 2008;8:89–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox P, Porter PG, Lob SH, Boer JH, Rocha DA, Adelson JW. Improving asthma-related health outcomes among low-income, multiethnic, school-aged children: results of a demonstration project that combined continuous quality improvement and community health worker strategies. Pediatrics 2007;120:e902–e911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cloutier MM, Jones GA, Hinckson V, Wakefield DB. Effectiveness of an asthma management program in reducing disparities in care in urban children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008;100:545–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bailey EJ, Cates CJ, Kruske SG, Morris PS, Brown N, Chang AB. Culture-specific programs for children and adults from minority groups who have asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;CD006580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.