Abstract

The alveolar epithelium serves as a barrier to the entry of potential respiratory pathogens. Alveolar Type II (TII) cells have immunomodulatory functions, but whether Type I (TI) cells, which comprise approximately 95% of the alveolar epithelium, also play a role in immunity is unknown. Because the renin–angiotensin system (RAS) is emerging as an important mediator of inflammation, and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), an element of the RAS, has been implicated in lung injury, we hypothesize that TI cells can produce cytokines in response to LPS stimulation, and that this inflammation can be modulated by the RAS. Alveolar TI cells were isolated from adult Sprague-Dawley rat lungs that had been injured with an intratracheal instillation of LPS. PCR was performed to determine whether TI cells expressed transcripts for TNF-α, IL-6, or IL-1β at baseline and after lung injury. Immunocytochemical and protein analysis detected angiotensin II (Ang II) and ACE2, as well as angiotensin Type 1 receptor (AT1R) and Type 2 receptor (AT2R), in TI cells. To separate cell-specific responses, primary TI cells were isolated, cultured, and exposed to LPS, Ang II, or specific inhibitors of AT1R or AT2R. Cytokine production was assayed by ELISA. LPS stimulated the production of all cytokines, whereas ACE2 and losartan, an AT1R inhibitor, blocked elements of the LPS-induced cytokine response. Primary TI cells produce cytokines when treated with LPS, contain important components of the RAS, and can modulate LPS-induced cytokine production via the RAS, suggesting a role for TI cells in the innate immune response of the lung.

Keywords: cytokines, alveolar Type I cells, angiotensin Type 1 receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, lipopolysaccharide

Clinical Relevance

Although alveolar Type II cells are known for their immunomodulatory functions, Type I cells have not been considered capable of participating in the immune response, although the vast surface area of Type I cells suggests that it is the first cell type encountered by respiratory pathogens entering the distal air spaces. Our study shows that Type I cells are capable of producing cytokines in response to LPS, and that Type I cell cytokine expression can be modulated by elements of the renin–angiotensin system. This study adds new data to the field of alveolar inflammation, and may lead to new therapies aimed at limiting inflammation and injury and hastening alveolar recovery and repair.

The alveolar epithelium serves as an interface between an organism and the environment, providing a tight barrier that permits gas exchange but inhibits the entry of respiratory pathogens. The area of the interface is large, measuring approximately 100–150 m2 in the human lung (1), and is primarily comprised of two different cell types: alveolar Type I (TI) and Type II (TII) cells. TII cells, which cover 2–5% of the internal surface area of the lung, are cuboidal, with diameters of approximately 10 μm. TII cells are considered defenders of the alveolus because they produce and secrete surfactant, which aids in the opsonization of bacteria (2). They also release cytokines and chemotactic factors that facilitate the recruitment of inflammatory cells to sites of alveolar injury (3, 4). In contrast, TI cells, which cover the remaining 95% of the lung’s internal surface area, are large, extremely thin squamous cells, with diameters measuring 50–100 μm (5). TI cells are not thought to participate in the inflammatory response. Cultured rat TII cells that have differentiated into TI-like cells can produce interferons in response to viral infections (6), but studies of primary TI cells are lacking, even though the extensive surface area covered by TI cells makes this the cell type most pathogens would first encounter upon entering the distal lung.

The renin–angiotensin system (RAS), which is vital in the regulation of blood pressure, electrolytes, and total body volume, also plays a role in inflammation (7, 8). Angiotensinogen (AGT) is cleaved by renin to produce angiotensin I, which is cleaved by the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) to produce Ang II, the effector molecule of the RAS. Ang II can then stimulate either the angiotensin Type 1 receptor (AT1R), leading to vasoconstriction, hypertension, fibroproliferation, and inflammation, or the angiotensin Type 2 receptor (AT2R), leading to the opposite effects of vasodilation, relative hypotension, apoptosis, and fibroprotection. LPS can increase Ang II concentrations in both the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and plasma of rats (9, 10), which may lead to AT1R stimulation and the promotion of cytokine production, thus reaffirming a role for the RAS in inflammation. Furthermore, angiotensin-converting enzyme–2 (ACE2), a metallopeptidase that primarily converts Ang II to angiotensins 1–7, has been reported in the alveolar epithelium (11) and is protective in acute lung injury (ALI), with recombinant ACE2 attenuating the degree of lung damage in multiple animal models of lung injury (12). These findings, along with the fact that TI cells line the vast majority of the interface between the lung and potential environmental pathogens, led us to hypothesize that TI cells could be involved in the immune response, and that the local RAS within the lung may be one means by which TI cells could mediate inflammation.

Materials and Methods

A more detailed account of our methods is provided in the online supplement.

Animal Studies

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Hollister, CA) were used in all experiments. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of California at San Francisco and the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Rats were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation before an intratracheal instillation of normal saline or 10 mg/kg LPS (Escherichia coli endotoxin serotype O127:B8; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) (13). Animals were killed 18 hours later with an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (100 mg/kg) before lung removal.

Alveolar Cell Isolation

Alveolar TI and TII cells were isolated by FACS (14), using antibodies specific to rat TI (RTI40) (15) or rat TII (RTII70) (16) cells (kind gifts of Dr. Leland Dobbs, University of California at San Francisco). Cell preparations containing more than 1% of the contaminating cells were discarded. More than 95% of all cells were viable, as measured by a Live/Dead Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). All biochemical experiments were performed with FACS TI or TII cells. A demonstration of purity is provided in the online supplement.

Cell Culture

Using the methods of Gonzales and Hubmayr (14) and Wang and colleagues (17), TI cells were cultured on trans-well plates at a density of 500,000 cells/cm2. TII cells were cultured as described by Dobbs (18). After allowing for recovery from the isolation procedure overnight, various reagents were added to the cells in serum-free media: LPS at 10 μg/ml, Ang II at 10−7 M, ACE2 at 0.025 μg/ml, losartan (LOS) at 10−3 M, and PD123319 at 10−5 M (Sigma-Aldrich). When multiple reagents were added, LPS was administered 30 minutes later. Cells were cultured for 18 hours before the collection of supernatant and cells.

PCR

Quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) was used to evaluate TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, ACE2, and AGT mRNA expression in TI and TII cells from uninjured and LPS-injured rat lungs and AT1R from cultured TI cells. Gene expression assays were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Carlsbad, CA). Relative amounts of mRNA were calculated using the comparative threshold method, with 18S RNA as the internal control.

Western Blot Analysis

Protein lysates from TI and TII cells were studied using standard Western blotting techniques. Antibodies included AT1R or AT2R (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich). Densitometric quantitation was performed using ImageJ software (www.NIH.gov).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on cytocentrifuged preparations of mixed rat lung cells. Antibodies included Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and ACE2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), Ang II (RayBiotech, Norcross, GA), RTI40, and RTII70. Secondary antibodies were conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 or 594 (Invitrogen). Control slides used a nonspecific IgG primary antibody.

Measurement of Cytokines via ELISA

Cell culture supernatants were assayed for TNF-α, IL-6, or IL-1β by ELISA, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed a minimum of three times unless otherwise stated. For comparisons between the control and treated groups, we used an unpaired Student t test. For comparisons of multiple groups, one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc analysis using the Bonferroni t test was performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Freshly Isolated TI Cell Cytokine mRNA Expression Can Be Up-Regulated by LPS

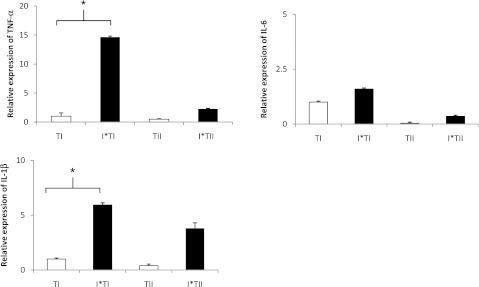

LPS is a potent activator of the innate immune response, with an early phase characterized by increased BAL polymorphonuclear leukocytes, cytokines, and protein, followed by a later phase occurring 24–48 hours after LPS instillation, marked by the normalization of BAL fluid cytokine concentrations (19). We chose the 18-hour time point to examine TI cell cytokine expression to ensure that the animals were sufficiently injured. The animals were administered intratracheal LPS (10 mg/kg) to induce ALI. Control animals were instilled with normal saline. TI and TII cells were isolated by FACS 18 hours later and then assayed for TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β mRNA, because they are classic proinflammatory cytokines that are up-regulated in LPS-induced lung injury. Transcripts for TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β were detected in TI cells from both control and LPS-injured animals. LPS injury significantly increased TNF-α and IL-1β transcript expression in TI cells compared with TI controls (*P < 0.05) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Freshly isolated alveolar Type I (TI) cell cytokine mRNA expression is up-regulated in LPS-induced lung injury. Expression of mRNA transcripts from freshly isolated FACS TI and alveolar Type II (TII) cells from animals administered intratracheal LPS (injured) or vehicle control was analyzed by quantitative PCR (Q-PCR). mRNA concentrations of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β were normalized to 18S, and are presented as arbitrary units reported as the means ± SEM of n = 4 separate experiments for TI cells and n = 5 separate experiments for TII cells. LPS injury significantly increased TNF-α and IL-1β mRNA expression in TI cells compared with TI control cells (*P < 0.05). I*TI, LPS-injured Type I cells; I*TII, LPS-injured Type II cells.

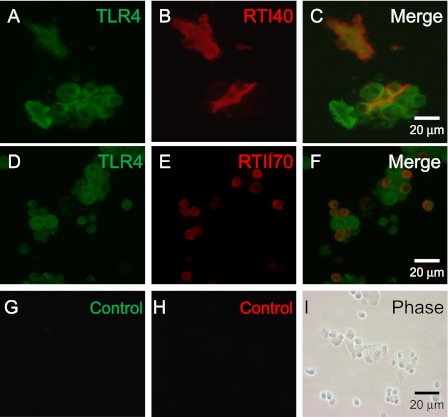

TI Cells Contain the LPS Receptor TLR4

Whether TI cells contained TLR4, the receptor for LPS, was unknown. Therefore, TLR4 expression in TI cells was assayed via immunocytochemistry. Mixed adult rat lung preparations from uninjured animals double-stained for TLR4 and either a TI or TII cell–specific antibody demonstrated colocalization of the signals, suggesting the presence of TLR4 in both TI and TII cells (Figure 2). Control images exhibited negative staining.

Figure 2.

TI cells express Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), a receptor for LPS. Adult rat lung cytocentrifuged mixed-cell preparations from uninjured rats were stained with an antibody to TLR4 and either RTI40, a TI cell–specific antibody, or RTII70, a TII cell–specific antibody. (A) Mixed lung cell preparation demonstrates TLR4 in multiple cell types. (B) The same slide section is stained with RTI40 to identify TI cells. (C) Merged image demonstrates the colocalization of TLR4 and TI cell marker, indicating the presence of TLR4 on TI cells. (D) Mixed lung cell preparation is stained with TLR4. (E) The same slide section is stained with RTII70 to identify TII cells. (F) Merged image demonstrates the presence of TLR4 on TII cells. (G) Control image uses a nonspecific primary antibody for TLR4. (H) Control image for RTI40. (I) Phase contrast image of cells in control slides. Image magnification, ×63.

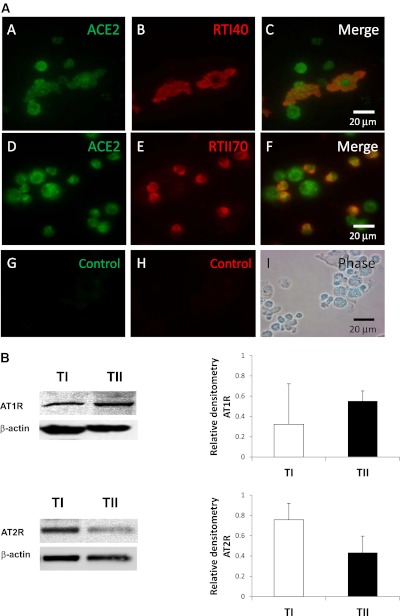

Components of the RAS Are Present in TI Cells

We hypothesized that TI cells could modulate the inflammatory response to LPS via the RAS. Thus, we needed to demonstrate that TI cells contained the crucial elements of the RAS. Mixed lung cell preparations were double-stained with ACE2 and an antibody specific to the apical surface of either TI or TII cells. Colocalization of ACE2 to specific cell membranes was visualized by a color shift upon merging the two fluorescent images, confirming that TI (and TII) cells contain ACE2 (Figure 3A). TI cells contain both AT1R and AT2R according to Western blotting (Figure 3B). Normalization to β-actin content demonstrated that TII cells have approximately 16% more AT1R protein than in TI cells, and that TI cells contain approximately 35% more AT2R protein than TII cells.

Figure 3.

(A) Immunohistochemical evidence of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in TI cells. Adult rat lung cytocentrifuged mixed-cell preparations from uninjured rats were stained with an antibody to ACE2 and either RTI40, a rat TI cell–specific antibody, or RTII70, a rat TII cell–specific antibody. (A, section A) Mixed lung cell preparation stained with ACE2. (A, section B) Same slide section was stained with the TI cell marker RTI40 to identify TI cells. (A, section C) Merged image demonstrates colocalization of ACE2 and TI cell marker, indicating the presence of ACE2 in TI cells. (A, section D) Mixed rat lung cell preparation was stained with ACE2. (A, section E) Same slide section was stained with RTII70 to identify TII cells. (A, section F) Merged image demonstrates the presence of ACE2 in TII cells. (A, section G) Control image uses a nonspecific primary antibody for ACE2. (A, section H) Control image for RTII70. (A, section I) Phase contrast image of cells in control slides. Image magnification, ×63. (B) Angiotensin Type 1 and Type 2 receptor protein expression in alveolar epithelial cells. Western blots of TI and TII cell lysates demonstrate the presence of angiotensin Type 1 receptor (AT1R; top panels) and angiotensin Type 2 receptor (AT2R; bottom panels) in both cell types. Cells were isolated by FACS. β-actin staining is shown to demonstrate the equalization of protein loading. Blots are representative of five separate experiments for each receptor. Right: Densitometry measurements are presented as graphs. Based on densitometry, TI cells contain approximately 16% less AT1R, but approximately 35% more AT2R, than TII cells.

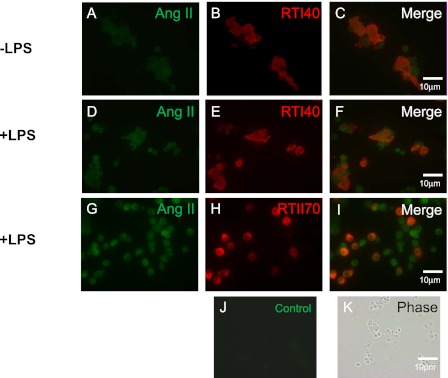

Ang II Is Expressed in the TI Cells of Both Uninjured and LPS-Injured Rats

Ang II mediates the effects of the RAS via its actions on AT1R and AT2R. LPS was shown to promote Ang II production in many cell types (9, 10), but whether LPS can increase Ang II concentrations in TI cells was not known. We detected Ang II in TI cells from mixed lung cell preparations of both LPS-injured and noninjured rat lungs, using immunocytochemistry. Furthermore, TI cells from LPS-treated animals appeared to have more intense Ang II staining, but no difference was evident in Ang II staining of TII cells from injured and noninjured lungs (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Angiotensin II (Ang II) is present in TI cells from both LPS-injured and uninjured rats. Cytocentrifuged preparations of adult rat mixed lung cells from uninjured (A–C) and LPS-injured (D–I) animals were double-stained with an antibody to Ang II and either RTI40, a TI cell marker, or RTII70, a TII cell marker. (A, D, and G) Mixed lung cell preparation was stained with Ang II. (B and E) Cells were stained with RTI40 to display TI cells. (H) Cells were stained with RTII70 to display TII cells. (C, F, and I) Merged images demonstrate colocalization of Ang II and either TI or TII cell–specific markers. (J) Control image shows lack of staining in the absence of a specific primary antibody. (K) Phase contrast image of the control slide. Image magnification, ×40. −, without; +, with.

LPS-Injured TI Cells Express Greater Concentrations of AGT mRNA than Do Control Cells

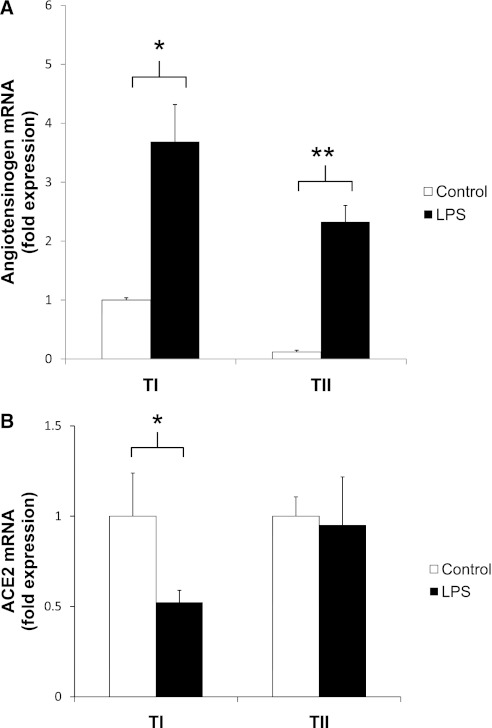

Q-PCR assays for AGT, the precursor to Ang II, demonstrated that TI cells from LPS-injured rats contained 3.5-fold higher concentrations of AGT than did TI cells from noninjured rats (*P < 0.05; Figure 5A). LPS-injured TII cells also contained significantly more AGT transcript than did their uninjured control rats (**P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

(A) Angiotensinogen, the precursor to Ang II, is up-regulated in TI cells after LPS injury. TI and TII cells were isolated via FACS from rats 18 hours after treatment with intratracheal LPS or vehicle control, and angiotensinogen (AGT) mRNA concentrations were measured using Q-PCR. Relative to the amount of transcript found in TI cells of control animals (n = 4), uninjured TII cells had lower AGT mRNA concentrations, whereas LPS injury increased AGT concentrations by 3.5-fold in TI cells (n = 4, *P < 0.05) and 12.5-fold in TII cells (n = 5). Data are expressed as fold expression of AGT mRNA over control values ± SEM, and all values were normalized to 18S. (B) LPS injury decreases ACE2 mRNA expression in freshly isolated TI cells. ACE2 mRNA concentrations were measured via Q-PCR in freshly isolated TI and TII cells, using FACS from rats that were treated with intratracheal LPS or vehicle control for 18 hours. A 48% reduction was evident in ACE2 transcripts in TI cells of LPS-injured animals (n = 3, *P < 0.05), but no difference was evident in ACE2 transcript levels in TII cells between control and injured animals (n = 3). Data are expressed as fold expression of ACE2 mRNA over control values ± SEM, and all values were normalized to 18S.

ACE2 mRNA Is Decreased in TI Cells of LPS-Injured Animals

Because ACE2 is protective in ALI, we queried whether there was a difference in ACE2 expression between injured and noninjured TI and TII cells. Via Q-PCR, a 48% reduction was evident in the quantity of ACE2 transcript in the TI cells of injured animals compared with control cells (Figure 5B). In TII cells, the concentrations of ACE2 transcript in both the control and LPS-treated animals were similar.

Cultured TI Cells Express TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β Protein via ELISA When Stimulated with LPS

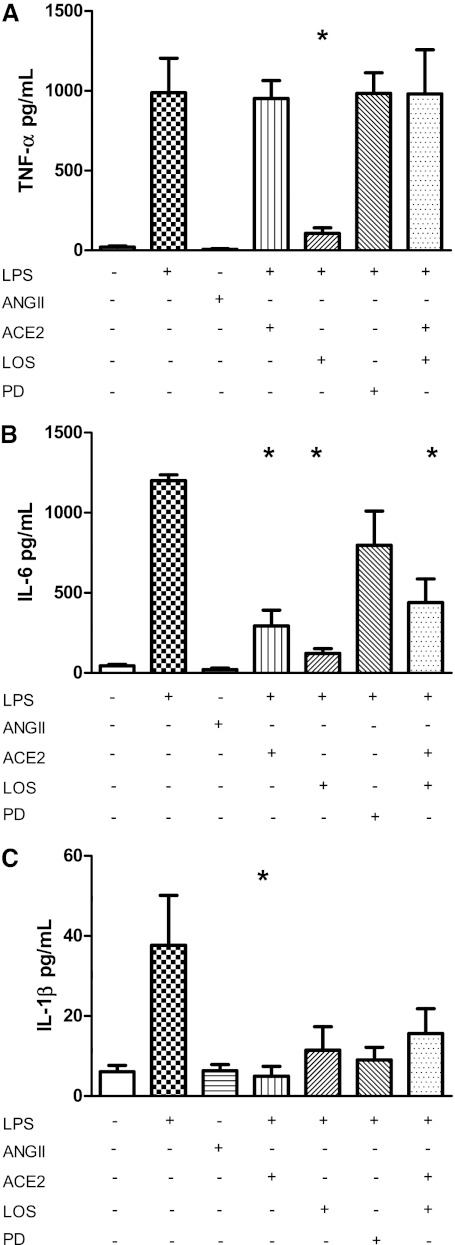

To measure the response of TI cells to LPS more accurately, primary rat alveolar TI cells were isolated via FACS and placed in culture, using methods outlined by Gonzalez and Hubmayr (14) and Wang and colleagues (17). Cells were allowed to recover from the isolation and FACS procedures overnight before treatment with 10 μg/ml LPS in serum-free media. Cells were incubated with LPS for 18 hours to parallel the timing of the LPS response in our whole-animal experiments. Control cells were treated with serum-free media alone. Afterward, both the supernatant and cells were collected. According to ELISA of the TI cell culture supernatants, TI cells produced a small amount of TNF-α at baseline (20.6 ± 6.5 pg/ml) (mean ± SEM). After LPS stimulation, TNF-α concentrations increased significantly (987.6 ± 216.9 pg/ml, *P < 0.05) (Figure 6A). Likewise, a significant increase was evident in IL-6 after stimulation with LPS (control cells, 44.4 ± 9.4 pg/ml; LPS, 1,200.2 ± 36.9 pg/ml; *P < 0.05) (Figure 6B), as well as in IL-1β (control cells, 6.1 ± 1.6 pg/ml; LPS, 37.8 ± 12.4 pg/ml; *P < 0.05) (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

The cytokine response from LPS stimulation in TI cells can be modulated by renin–angiotensin system (RAS) elements. Above: Cytokine concentrations from the supernatant of FACS cultured TI cells were measured by ELISA (in pg/ml) after incubation with various reagents for 18 hours. Below: Tables demonstrates which reagents were added to the different series of cultured TI cells. Comparisons are drawn in reference to LPS-stimulated cells. Results are expressed as mean concentrations of cytokine (in pg/ml) ± SEM. (A) Cultured TI cells produce a small amount of TNF-α at baseline (n = 5), but LPS stimulation significantly increased TNF-α release (n = 5). Ang II alone did not increase TNF-α concentrations. Pretreatment with ACE2 before LPS treatment did not alter TNF-α expression over baseline levels. However, pretreatment with losartan (LOS) before LPS treatment significantly decreased TNF-α concentrations (n = 6, *P < 0.05). Pretreatment with AT2R-specific inhibitor PD123319 (PD) or ACE2 + LOS before LPS treatment (each n = 3) produced no change in TNF-α concentrations, compared with LPS alone. (B) IL-6 concentrations increased significantly after LPS treatment (n = 4, *P < 0.05). Results with Ang II alone (n = 3) were no different from those of control samples. ACE2 pretreatment before LPS treatment inhibited IL-6 by 75.6%, compared with LPS alone (n = 6, *P < 0.05). Likewise, LOS treatment also reduced LPS-stimulated IL-6 by 87.3% (n = 6, *P < 0.05). PD administered before LPS treatment did not significantly alter IL-6 production (n = 3). ACE2 + LOS pretreatment before LPS treatment significantly decreased IL-6 production by 63.4% (n = 3, *P < 0.05), compared with LPS-treated cells. (C) LPS treatment significantly increased IL-1β concentrations over those in control samples (n = 3 for each condition, *P < 0.05). ACE2 pretreatment before LPS treatment significantly blocked IL-1β release from LPS-stimulated cells by 86.7% (n = 6, *P < 0.05). Pretreatment with either LOS (n = 6), ACE2 + LOS (n = 6), or PD (n = 6) before LPS treatment decreased the absolute concentrations of IL-1β, but these numbers did not achieve statistical significance.

ACE2 Inhibits LPS-Stimulated IL-6 and IL-1β from Cultured TI Cells

Although the exact mechanism of how ACE2 abrogates lung inflammation is not known, ACE2 could cleave the Ang II that was up-regulated by LPS, thereby decreasing the ability of Ang II to act on AT1R to induce inflammation. We explored whether the LPS-induced cytokine response in TI cells could be attenuated by exogenous ACE2. Cells were treated with ACE2 30 minutes before the addition of LPS. Supernatants were collected 18 hours later. ACE2 treatment before LPS treatment significantly decreased IL-6 concentrations by 75.6% (292.8 ± 98.4 pg/ml, *P < 0.05) (Figure 6B) and IL-1β concentrations by 86.7% (5.0 ± 2.1 pg/ml, *P < 0.05) (Figure 6C), compared with LPS-stimulated cells alone. ACE2 did not change TNF-α concentrations in LPS-stimulated TI cells (951.9 ± 111.9 pg/ml) (Figure 6A).

Ang II Did Not Increase TI Cell Cytokine Production

Because Ang II is thought to stimulate AT1R to induce inflammation, we hypothesized that Ang II was sufficient to stimulate cytokine production. Ang II 10−7 M was added alone to cultured TI cells, and the supernatants were collected 18 hours later. Ang II did not increase supernatant cytokine concentrations above control levels (TNF-α, 7.0 ± 3.6 pg/ml; IL-6, 21.2 ± 9.4 pg/ml; IL-1β, 6.3 ± 1.5 pg/ml) (Figures 6A–6C). Although Ang II at higher concentrations increased the expression level of TNF-α, but not IL-6 (see Figures E5 and E6 in the online supplement), the inducible effect was modest when compared with LPS treatment.

Losartan Inhibits the Production of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in LPS-Treated TI Cells

LOS, a specific AT1R inhibitor, can decrease the inflammatory response in some animal models of ALI (20, 21). LOS was added to cultured TI cells 30 minutes before the addition of LPS, and cytokine concentrations were measured 18 hours later. When compared with LPS stimulation alone, LOS significantly inhibited TNF-α secretion from LPS-stimulated TI cells by 89.2% (106.9 ± 34.4 pg/ml, *P < 0.05) (Figure 6A) and IL-6 secretion by 87.3% (152.5 ± 29.8 pg/ml, *P < 0.05) (Figure 6B). IL-1β was similarly reduced, but the degree of inhibition was not statistically significant (Figure 6C).

PD123319, an AT2R Inhibitor, Does Not Alter Cytokine Concentrations in LPS-Treated TI Cells

AT2R activation yields vasodilatation, fibroprotection, and apoptosis, in direct contrast to AT1R stimulation. In cultured TI cells, pretreatment with PD123319 (PD) 30 minutes before LPS stimulation did not alter TNF-α (984.1 ± 129.2 pg/ml) (Figure 6A) or IL-6 (796.3 ± 214.4 pg/ml) (Figure 6B) secretion at 18 hours when compared with LPS stimulation alone. IL-1β concentrations (9.0 ± 3.1 pg/ml) were reduced with PD administration, but this decrease was not statistically significant (Figure 6C).

The Combination of RAS Reagents on Cytokine Production in LPS-Treated TI Cells Was Only Notable for IL-6

To elucidate the various effects of AT1R, AT2R, and ACE2 on cultured TI cells, we added reagents in concert and then measured supernatant cytokine concentrations 18 hours later. The addition of ACE2 + LOS together before LPS stimulation was predicted to reduce cytokine concentrations in TI cells, because each agent alone decreased IL-6 and IL-1β production. TNF-α concentrations were reduced by LOS, but remained unchanged with exogenous ACE (Figure 6A). Interestingly, TNF-α concentrations in TI cells pretreated with ACE2 + LOS before LPS treatment were not significantly different from TNF-α concentrations in LPS-alone–treated cells (980.7 ± 276.4 pg/ml). However, ACE2 + LOS decreased IL-6 concentrations by 63.4% (438.9.0 ± 148.1 pg/ml, *P < 0.05) (Figure 6B). IL-1β concentrations were also decreased (15.6 ± 5.7 pg/ml), but this decrease did not reach statistical significance (Figure 6C).

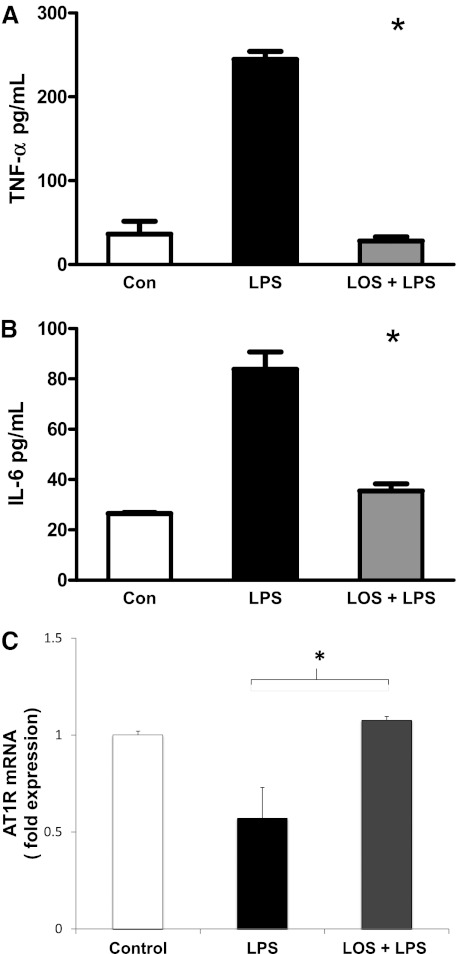

Losartan Decreases LPS-Induced TNF-α and IL-6 Production within 3 Hours

To determine whether AT1R inhibition acts as an immediate effector of LPS-induced signaling or acts indirectly by promoting the effects of other mediators induced by LPS, we measured the LOS-induced inhibition of cytokine expression at an earlier time point (i.e., 3 hours). Although the overall degree of cytokine production was slightly lower than noted at 18 hours (as expected), LOS reduced LPS-stimulated TNF-α (Figure 7A) and IL-6 (Figure 7B) production by 90% and 58%, respectively (n = 3 for each experiment, *P < 0.05), suggesting that RAS modulation may act directly on LPS-induced signaling.

Figure 7.

Insights into RAS modulation of TI cell inflammation. (A) LOS decreased LPS-induced TNF-α production within 3 hours. Cultured TI cells were treated with serum-free medium alone, 10 μg/ml LPS, or LOS (10−3 M) + LPS. TNF-α secretion was assayed via ELISA. LOS decreased LPS-induced TNF-α by 90% within 3 hours (*P < 0.05). (B) LOS decreased LPS-induced IL-6 production within 3 hours. Cultured TI cells were treated with serum-free medium alone, 10 μg/ml LPS, or LOS (10−3 M) + LPS. IL-6 secretion was assayed via ELISA. LOS decreased LPS-induced IL-6 production by 58% in as early as 3 hours (*P < 0.05). (C) LOS disrupts feedback inhibition of AT1R transcript expression. AT1R mRNA concentrations were measured via Q-PCR in cultured TI cells treated with LPS or LOS (10−3 M) + LPS for 18 hours. Control cells (Con) were treated with serum-free medium. A 42% reduction was evident in AT1R transcripts in LPS-treated cells compared with control cells, and this reduction was corrected by the addition of LOS (10−3 M) before LPS treatment (n = 3, *P < 0.05). Data are expressed as fold expression of AT1R mRNA over control values ± SEM, and all values were normalized to 18S.

AT1R Transcript Expression May Be Feedback-Inhibited

Some studies suggest that LPS increases AT1R transcription, leading to further cytokine expression (22). We discovered that after 18 hours, LPS-treated cultured TI cells have approximately 50% of the AT1R transcript expression of control TI cells, and that the addition of LOS before LPS treatment brought AT1R transcript expression back to control levels. These findings suggest that AT1R may be feedback-inhibited, and that LOS may interfere with this pathway (Figure 7C).

Discussion

The barrier formed by the alveolar epithelium is the first line of defense against inhaled pathogens in the distal lung. Macrophages and monocytes, along with TII cells, have traditionally been considered the cells that trigger the immune response to inhaled pathogens. Given that TI cells cover the majority of the alveolar epithelium, we postulated that TI cells would also be able to activate the immune response when respiratory pathogens are encountered.

Although immune cells produce the majority of total BAL cytokines and chemokines, precisely which pulmonary cells are involved, and their specific contributions to the cytokine/chemokine content of the BAL, are not entirely known. Limited data are available on the contribution of TII cells to BAL cytokine content, and no data are available on the contribution of primary TI cells, so we first examined cytokine expression in TI (and TII) cells of animals injured with intratracheal LPS. Transcripts for TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β were present in both control (uninjured) and LPS-injured TI cells. Similar results were observed in TII cells, as previously reported (4, 23–25). Injured TI cells expressed significantly more TNF-α and IL-1β mRNA than uninjured TI cells, whereas the IL-6 mRNA expression of injured and uninjured TI cells remained similar. IL-1β can induce IL-6 production in monocytes and fibroblasts (26), and thus the IL-1β response observed may precede that of IL-6. Nonetheless, our results demonstrate the novel finding that primary TI cells contain the necessary transcripts for cytokine production.

Most of the well-known effects of the RAS target the cardiovascular system, but evidence exists that the RAS produces directed effects in other organs and tissues, including the lung. Ang II is considered the effector molecule of the RAS, because it interacts with the G-protein coupled receptors AT1R and AT2R. AT1R can induce the activation of transcription factors NF-κB and activating protein 1 (AP-1) to induce cytokine expression (27, 28), vasoconstriction, fibroproliferation, the retention of Na+, and the enhancement of lung injury. AT2R produces effects opposite those of AT1R stimulation (primarily vasodilation, the inhibition of cell growth, and apoptosis). Ang II can be converted to Ang-(1–7) by ACE2, and Ang-(1–7) can act on the Mas receptor to produce effects similar to those of AT2R activation. Thus a balancing of the arms of the RAS seems to occur, with ACE–Ang II–AT1R representing the injury-promoting arm, and ACE2–Ang-(1–7)–AT2R representing the injury-protective arm (29).

We postulate that LPS-stimulated cytokine production in TI cells can be modulated by the RAS. LPS can increase Ang II concentrations in certain cell types (9, 10), but whether LPS could induce TI cell Ang II production was unknown. We detected Ang II in TI and TII cells from both uninjured and injured rat lungs. Ang II staining appeared brighter in TI cells from LPS-injured animals, but was similar in TII cells from uninjured and injured lungs. We attempted to measure Ang II concentrations via ELISA of the supernatants of cultured TI cells stimulated with LPS, but our results were consistently below the detection level of the assay (1 pg/ml). Ultimately, this was not surprising, because the half-life of Ang II is approximately 0.6 minutes in plasma (30) and 15 minutes in local tissue compartments (31). Therefore, we measured the presence of the precursor to Ang II, AGT, in TI cells. According to Q-PCR, AGT expression was 3.5-fold higher in the TI cells of LPS-injured rats compared with uninjured control rats, suggesting that LPS can increase cytokine expression in TI cells by increasing AGT, which can be converted to Ang II, and Ang II can then act on AT1R to induce inflammation. Similar findings were evident in TII cells.

Inflammation can also be regulated by ACE2. An elegant study by Imai and colleagues (12) demonstrated the protective nature of ACE2 in ALI, with ACE2−/− mice developing more severe ALI, and recombinant ACE2 attenuating lung damage. In the LPS-injured lung, we detected approximately 50% less ACE2 transcript in TI cells than in TI cells from uninjured lungs after 18 hours, but no difference in ACE2 transcript in TII cells of LPS-treated versus control animals. In murine models of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), total lung ACE2 concentrations were decreased as the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) down-regulated its receptor, ACE2, upon infection (32). Although no studies suggest that LPS directly down-regulates ACE2 expression, there are data that Ang II can decrease ACE2 mRNA by 60% in certain cell types, such as astrocytes (33). Furthermore, because approximately 35% more AT2R is present in TI versus TII cells, LPS may increase Ang II in TI cells, but Ang II may preferentially bind AT2R, decreasing AT1R stimulation, which may feed back on the system and reduce ACE2 concentrations. At the very least, this decrease in ACE2 mRNA in LPS-treated TI, but not TII, cells and the difference in AT1R and AT2R receptor densities suggest differential regulation of the RAS between the two cell types.

By isolating TI cells from LPS-injured rat lungs, we studied the effects of the inflammatory milieu (e.g., macrophages, endothelia, TII cells, plasma factors, and surfactant) on TI cells. To isolate cell-specific responses to LPS stimulation, we moved to an in vitro model. We isolated relatively pure populations of TI cells via FACS and placed them in culture. Because the isolation process and FACS alone may have stimulated cytokine production, we allowed the cells to recover overnight (34) and then studied the cells 18 hours later, to parallel the time points used in our injured animal model.

We measured cytokine concentrations from the supernatants of cultured primary TI cells according to ELISA. Control TI cells produced minimal amounts of all three cytokines, the concentrations of which increased after LPS exposure. Recent reports of TNF-α concentrations in primary TII cell cultures range from approximately 800–1,000 pg/ml 24 hours after LPS stimulation, at doses ranging from 0.01–10 μg/ml (23, 24, 35, 36). The lack of data on cytokine expression in cultured TI cells precludes similar comparisons, but our results for TI cells appear to involve the same range as those for TII cells. Published IL-1β and IL-6 concentrations for cultured TII cells were likewise within the range of results obtained for TI cells.

Dose–response experiments with LPS demonstrated that 10 μg/ml LPS added to cultured TI cells produced the greatest degree of TNF-α stimulation, although smaller concentrations also increased TNF-α concentrations. Because we desired the maximum cytokine expression to better visualize the effects of inhibitors to cytokine production, and because this occurred most reliably with 10 μg/ml LPS, we used that concentration in our studies, which is a dose used by other investigators in studies of TII cell cytokine expression (24, 25) (see the online supplement).

Ang II alone added to TI cells did not increase cytokine expression, as initially expected. Ang II can stimulate TNF-α and IL-6 production in other epithelial cells, but this required a continuous infusion of Ang II (7). Given the short half-life of Ang II, averaging only 15 minutes in local tissue compartments (31), our single dose may have been insufficient to elicit a significant cytokine response, and a continuous infusion of Ang II may be necessary to prompt significant cytokine production. Ang II induces apoptosis in rat TII cells (37, 38), which may also account for the lack of robust cytokine expression. However, we did not detect any significant reduction in TI cell viability after treatment with Ang II at 10−7 M for 18 hours.

We expected ACE2 to reduce endogenous Ang II concentrations and decrease cytokine production. ACE2 decreased the production of IL-6 and IL-1β in LPS-stimulated TI cells, but not the production of TNF-α. ACE2 can cleave other substrates such as neurotensin and des-Arg9-bradykinin, leading to a proinflammatory response (39). Thus, ACE2 in TI cells could be both anti-inflammatory (decreased IL-6 and IL-1β) and proinflammatory (increased TNF-α), which is not inconsistent with the actions of the RAS, which attempts to balance physiologic responses. Moreover, because ACE2 concentrations in LPS-treated TI cells are already reduced by approximately 50%, we may not have added enough ACE2 to overcome this deficit and induce lung-protective effects. However, our dose–response experiments with ACE2 found no difference in TI supernatant TNF-α production after the addition of 0.00025 μg/ml to 0.25 μg/ml ACE2 (data not shown). Moreover, TI cells contain approximately 35% more AT2R than do TII cells, suggesting that TI cells, although they can produce cytokines in response to LPS exposure, may be more prominent in the injury-protective, rather than the injury-promoting, arm of the RAS.

LOS decreased cytokine concentrations in LPS-stimulated TI cells, which was expected, given that AT1R inhibition decreases cytokine production in multiple cell and animal models. Conversely, the addition of the AT2R-specific inhibitor PD123319 did not produce statistically different results from those of LPS alone, which was also expected. A trend toward a decrease in IL-6 and IL-1β production was evident, but this may represent the cross-reactivity of AT2R inhibitors in the less studied angiotensin receptors AT3R and AT4R. Alternately, the down-regulation of AT1R may occur with AT2R inhibition, thus reducing the inflammatory response.

The combination of ACE2 + LOS before LPS stimulation was predicted to reduce cytokine concentrations in TI cells, because each agent alone decreased IL-6 and IL-1β production. TNF-α concentrations were significantly reduced by LOS, but remained unchanged with exogenous ACE2. Interestingly, TNF-α concentrations in TI cells pretreated with ACE2 + LOS before LPS treatment were not significantly different from TNF-α concentrations in LPS-alone treated cells. However, ACE2 + LOS significantly decreased concentrations of IL-6. IL-1β concentrations were also lower, but the decrease did not achieve statistical significance. These findings suggest that TNF-α may be more sensitive to the Ang II activation of AT1R than are IL-6 and IL-1β. Alternately, IL-6 and IL-1β may be more sensitive than TNF-α to the effects of Ang-(1–7), which can inhibit the inflammatory response. Of note, the effects of ACE2 + LOS are not additive. In contrast, although each component alone reduced cytokine concentrations, ACE2 + LOS increased cytokine concentrations, prompting questions of whether ACE2 may interact with LOS or modify AT1R to reduce signaling efficacy, or if LOS can independently down-regulate AT1R (40, 41). Alternately, these results suggest that AT1R inhibition may be the more biologically significant response, and that Ang II may act via other less-well characterized pathways to produce these mixed effects. ACE inhibitors or AT1R antagonists were reported to attenuate the inflammatory response in animal models of ALI (8, 42), but similar large-scale studies in humans have yet to be performed.

The precise mechanism by which the RAS can modulate TI cell inflammation remains elusive. To see if the RAS acts immediately on LPS-induced signaling or if the observed effects arise from the indirect influence of the RAS on other mediators produced by LPS, we measured TNF-α and IL-6 production in the presence of LPS and LOS (10−3 M) + LPS at 3 hours. LPS increased cytokine expression, although at a reduced level, which was expected. The addition of LOS before LPS treatment significantly reduced the expression of both cytokines, suggesting that the RAS acts rather quickly on LPS-induced signaling. Furthermore, we investigated the effects of LPS and LOS on AT1R expression in cultured TI cells, given that some studies suggest that TLR4 activation up-regulates AT1R transcript expression (43). We instead found that after 18 hours, LPS decreased AT1R mRNA expression, and that the decrease could be abrogated by the addition of LOS before LPS treatment. An LPS-induced decrease in AT1R expression was observed by other investigators in whole rat lungs (21) and in human mesangial cells (44). These findings suggest that LPS may induce a feedback inhibition of AT1R to prevent unbridled inflammation, and that LOS disrupts this feedback loop. Future studies will need to determine whether AT1R mRNA expression translates into similar protein results.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that primary alveolar TI cells produce cytokines in response to LPS. Showing that the cell type that comprises more than 95% of the alveolar epithelium is able to produce cytokines in response to LPS speaks to the ability of TI cells to play a role in alveolar inflammation. We have also demonstrated that TI cell cytokine expression can be modulated by elements of the RAS, which affords us not just another instrument, but a veritable orchestra by which we can investigate the alveolar inflammatory response. These studies imply that TI cells may serve as targets for the development of new therapeutic and preventive tools to regulate alveolar inflammation, to assist in controlling lung injury, and to promote alveolar repair.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Leland Dobbs for his gift of antibodies, Dr. Phil Ballard and Dr. Dobbs for their helpful discussions, and Chong Cha Johnson for her support.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and by grant HL088025 from the National Institutes of Health (M.D.J).

Some of this work was previously presented in poster form.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0289OC on December 28, 2011

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Weibel ER. Principles and methods for the morphometric study of the lung and other organs. Lab Invest 1963;12:131–155 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright JR. Host defense functions of pulmonary surfactant. Biol Neonate 2004;85:326–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paine R, III, Rolfe MW, Standiford TJ, Burdick MD, Rollins BJ, Strieter RM. MCP-1 expression by rat Type II alveolar epithelial cells in primary culture. J Immunol 1993;150:4561–4570 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanderbilt JN, Mager EM, Allen L, Sawa T, Wiener-Kronish J, Gonzalez R, Dobbs LG. CXC chemokines and their receptors are expressed in Type II cells and upregulated following lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2003;29:661–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stone KC, Mercer RR, Freeman BA, Chang LY, Crapo JD. Distribution of lung cell numbers and volumes between alveolar and nonalveolar tissue. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992;146:454–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miura TA, Wang J, Holmes KV, Mason RJ. Rat coronaviruses infect rat alveolar Type I epithelial cells and induce expression of CXC chemokines. Virology 2007;369:288–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruiz-Ortega M, Ruperez M, Lorenzo O, Esteban V, Blanco J, Mezzano S, Egido J. Angiotensin II regulates the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the kidney. Kidney Int Suppl 2002;82:S12–S22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jerng JS, Hsu YC, Wu HD, Pan HZ, Wang HC, Shun CT, Yu CJ, Yang PC. Role of the renin–angiotensin system in ventilator-induced lung injury: an in vivo study in a rat model. Thorax 2007;62:527–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yasuda S, Lew WY. Angiotensin II exacerbates lipopolysaccharide-induced contractile depression in rabbit cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol 1999;276:H1442–H1449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H, Sun GY. LPS induces permeability injury in lung microvascular endothelium via AT(1) receptor. Arch Biochem Biophys 2005;441:75–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haagmans BL, Kuiken T, Martina BE, Fouchier RA, Rimmelzwaan GF, van Amerongen G, van Riel D, de Jong T, Itamura S, Chan KH, et al. Pegylated interferon-alpha protects type 1 pneumocytes against SARS coronavirus infection in macaques. Nat Med 2004;10:290–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imai Y, Kuba K, Rao S, Huan Y, Guo F, Guan B, Yang P, Sarao R, Wada T, Leong-Poi H, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature 2005;436:112–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moxley MA, Baird TL, Corbett JA. Adoptive transfer of acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2000;279:L985–L993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez RF, Allen L, Dobbs LG. Rat alveolar Type I cells proliferate, express OCT-4, and exhibit phenotypic plasticity in vitro. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2009;297:L1045–L1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez RF, Dobbs LG. Purification and analysis of RTI40, a Type I alveolar epithelial cell apical membrane protein. Biochim Biophys Acta 1998;1429:208–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutierrez JA, Gonzalez RF, Dobbs LG. Mechanical distension modulates pulmonary alveolar epithelial phenotypic expression in vitro. Am J Physiol 1998;274:L196–L202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang S, Hubmayr RD. Type I alveolar epithelial phenotype in primary culture. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2011;44:692–699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dobbs LG. Isolation and culture of alveolar Type II cells. Am J Physiol 1990;258:L134–L147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Grady NP, Preas HL, Pugin J, Fiuza C, Tropea M, Reda D, Banks SM, Suffredini AF. Local inflammatory responses following bronchial endotoxin instillation in humans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:1591–1598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hagiwara S, Iwasaka H, Matumoto S, Hidaka S, Noguchi T. Effects of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor on the inflammatory response in in vivo and in vitro models. Crit Care Med 2009;37:626–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu L, Qiu HB, Yang Y, Wang L, Ding HM, Li HP. Losartan, an antagonist of AT1 receptor for angiotensin II, attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in rat. Arch Biochem Biophys 2009;481:131–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang F, Xia ZF, Chen XL, Jia YT, Wang YJ, Ma B. Angiotensin II Type–1 receptor antagonist attenuates LPS-induced acute lung injury. Cytokine 2009;48:246–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanj RS, Kang JL, Castranova V. Measurement of the release of inflammatory mediators from rat alveolar macrophages and alveolar Type II cells following lipopolysaccharide or silica exposure: a comparative study. J Toxicol Environ Health A 2005;68:185–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crestani B, Cornillet P, Dehoux M, Rolland C, Guenounou M, Aubier M. Alveolar Type II epithelial cells produce interleukin-6 in vitro and in vivo: regulation by alveolar macrophage secretory products. J Clin Invest 1994;94:731–740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McRitchie DI, Isowa N, Edelson JD, Xavier AM, Cai L, Man HY, Wang YT, Keshavjee SH, Slutsky AS, Liu M. Production of tumour necrosis factor alpha by primary cultured rat alveolar epithelial cells. Cytokine 2000;12:644–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tosato G, Jones KD. Interleukin-1 induces interleukin-6 production in peripheral blood monocytes. Blood 1990;75:1305–1310 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dinh DT, Frauman AG, Johnston CI, Fabiani ME. Angiotensin receptors: distribution, signalling and function. Clin Sci (Lond) 2001;100:481–492 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braz JC, Bueno OF, De Windt LJ, Molkentin JD. PKC alpha regulates the hypertrophic growth of cardiomyocytes through extracellular signal–regulated kinase1/2 (ERK1/2). J Cell Biol 2002;156:905–919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steckelings UM, Rompe F, Kaschina E, Unger T. The evolving story of the RAAS in hypertension, diabetes and CV disease: moving from macrovascular to microvascular targets. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2009;23:693–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wenz M, Steinau R, Gerlach H, Lange M, Kaczmarczyk G. Inhaled nitric oxide does not change transpulmonary angiotensin II formation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Chest 1997;112:478–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Kats JP, de Lannoy LM, Jan Danser AH, van Meegen JR, Verdouw PD, Schalekamp MA. Angiotensin II Type 1 (AT1) receptor–mediated accumulation of angiotensin II in tissues and its intracellular half-life in vivo. Hypertension 1997;30:42–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuba K, Imai Y, Rao S, Gao H, Guo F, Guan B, Huan Y, Yang P, Zhang Y, Deng W, et al. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus–induced lung injury. Nat Med 2005;11:875–879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gallagher PE, Chappell MC, Ferrario CM, Tallant EA. Distinct roles for ANG II and ANG-(1–7) in the regulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in rat astrocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2006;290:C420–C426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corti M, Brody AR, Harrison JH. Isolation and primary culture of murine alveolar Type II cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1996;14:309–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang F, Wang X, Wang W, Li N, Li J. Glutamine reduces TNF-alpha by enhancing glutathione synthesis in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated alveolar epithelial cells of rats. Inflammation 2008;31:344–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thorley AJ, Ford PA, Giembycz MA, Goldstraw P, Young A, Tetley TD. Differential regulation of cytokine release and leukocyte migration by lipopolysaccharide-stimulated primary human lung alveolar Type II epithelial cells and macrophages. J Immunol 2007;178:463–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang R, Alam G, Zagariya A, Gidea C, Pinillos H, Lalude O, Choudhary G, Oezatalay D, Uhal BD. Apoptosis of lung epithelial cells in response to TNF-alpha requires angiotensin II generation de novo. J Cell Physiol 2000;185:253–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bechara RI, Brown LA, Eaton DC, Roman J, Guidot DM. Chronic ethanol ingestion increases expression of the angiotensin II Type 2 (AT2) receptor and enhances tumor necrosis factor–alpha– and angiotensin II–induced cytotoxicity via AT2 signaling in rat alveolar epithelial cells. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2003;27:1006–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Donoghue M, Hsieh F, Baronas E, Godbout K, Gosselin M, Stagliano N, Donovan M, Woolf B, Robison K, Jeyaseelan R, et al. A novel angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin 1-9. Circ Res 2000;87:E1-E9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh R, Mackraj I, Naidoo R, Gathiram P. Sanguinarine downregulates AT1a gene expression in a hypertensive rat model. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2006;48:14–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stegbauer J, Lee DH, Seubert S, Ellrichmann G, Manzel A, Kvakan H, Muller DN, Gaupp S, Rump LC, Gold R, et al. Role of the renin–angiotensin system in autoimmune inflammation of the central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009;106:14942–14947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang JS, Wang LF, Chou HC, Chen CM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor captopril attenuates ventilator-induced lung injury in rats. J Appl Physiol 2007;102:2098–2103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishida M, Suda R, Nagamatsu Y, Tanabe S, Onohara N, Nakaya M, Kanaho Y, Shibata T, Uchida K, Sumimoto H, et al. Pertussis toxin up-regulates angiotensin Type 1 receptors through Toll-like receptor 4–mediated Rac activation. J Biol Chem 2010;285:15268–15277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maquigussa E, Arnoni CP, Cristovam PC, de Oliveira AS, Higa EM, Boim MA. Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide impairs the calcium signaling pathway in mesangial cells: role of angiotensin II receptors. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2010;235:761–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.