Abstract

Chemokines and chemokine receptors have been implicated in the pathogenesis of bronchiolitis. CXCR3 ligands (CXCL10, CXCL9, and CXCL11) were elevated in patients with bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) and chronic allorejection. Studies also suggested that blockage of CXCR3 or its ligands changed the outcome of T-cell recruitment and airway obliteration. We wanted to determine the role of the chemokine CXCL10 in the pathogenesis of bronchiolitis and BOS. In this study, we found that CXCL10 mRNA levels were significantly increased in patients with BOS. We generated transgenic mice expressing a mouse CXCL10 cDNA under control of the rat CC10 promoter. Six-month-old CC10-CXCL10 transgenic mice developed bronchiolitis characterized by airway epithelial hyperplasia and developed peribronchiolar and perivascular lymphocyte infiltration. The airway hyperplasia and T-cell inflammation were dependent on the presence of CXCR3. Therefore, long-term exposure of the chemokine CXCL10 in the lung causes bronchiolitis-like inflammation in mice.

Keywords: bronchiolitis, chemokine CXCL10, inflammation, airway inflammation

Clinical Relevance

The role for CXCR3 receptor–ligand interactions in allorejection and obliterative airway disease is controversial. The current study used a genetics approach to demonstrate that long-term exposure of CXCL10 to the lung is sufficient to cause airway inflammation characterized by airway epithelial hyperplasia as well as peribronchial and perivascular lymphatic infiltration in a CXCR3-dependent manner, offering potential therapeutic targets to prevent the development of bronchiolitis.

Acute bronchiolitis is a disorder most commonly found in infants. It is caused by viral lower respiratory tract infection characterized by inflammation, edema, and necrosis of epithelial cells lining the small airways; increased mucus production; and bronchospasm (1). Chronic bronchiolitis is characterized by a hyperplasia of lymphoid tissue along the airways (including the large and the medial bronchi) and by the development of follicles and follicular centers (2). A persistent peribronchiolar inflammation gives way to airway fibrosis and obliteration, leading to bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS). BOS is the major limitation to survival after lung or bone marrow transplantation (3, 4). The follicles can obstruct the bronchiolar lumen, and the obstruction leads to secondary infection and peribronchiolar pneumonia (2). There is an increase in activated CD8+ cells in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid in patients with diffuse panbronchiolitis (5). T-helper 1 cytokines and chemokine expression are up-regulated in posttransplant airway obliteration (6). Higher concentrations of IL-6 and IL-8 in bronchial and alveolar fractions of the BAL were significantly associated with an increased risk of developing BOS (7).

Chemokines are released during tissue injury and play a critical role in regulating cytokine production and leukocyte recruitment, in engendering the adaptive immune responses, and in the pathogenesis of many human diseases (8). CXC chemokines CXCL10 (IFN-γ–induced protein 10-kD), CXCL9 (monokine induced by IFN-γ), and CXCL11 (IFN-inducible T cell a chemoattractant) bind to their receptor CXCR3. Their expression is dramatically up-regulated by IFN-γ (9). CXCR3 is preferentially expressed on Th1 cells (10). CXCR3 and its ligands act primarily on activated T and natural killer (NK) cells and have been implicated in mediating the effects of IFN-γ as well as of T cell–dependent inflammatory responses (11). CXCR3 ligands that attract Th1 cells can concomitantly block the migration of Th2 cells in response to CCR3 ligands, thus enhancing the polarization of effector T-cell recruitment (11).

CXCL10 is induced during infectious and noninfectious tissue injuries such as liver ischemia/reperfusion injury (12), respiratory syncytial viral infection (13), and chronic hepatitis C virus infection (14). CXCL10 also plays a critical role in host defense (15). Indeed, the blockage of CXCR3–CXCL10 interaction with anti-CXCL10 antisera in mice led to increased mortality and delayed viral clearance from the central nervous system as compared with control mice when infected with mouse hepatitis virus (16). Similarly, mice deficient in CXCL10 infected with hepatitis virus had an impaired ability to control viral replication in the brain (17). The elevated levels of CXCR3 chemokines in human BAL fluid were associated with the continuum from acute to chronic rejection (18). CXCR3 and its ligand CXCL10 are expressed by inflammatory cells infiltrating lung allografts and mediate chemotaxis of T cells at sites of rejection (19, 20). Furthermore, in vivo blockage of CXCR3 receptor–ligand interactions with neutralizing antibodies to receptor CXCR3 or to the ligands CXCL9 and CXCL10 decreased intragraft recruitment of CXCR3-expressing mononuclear cells and attenuated BOS (18). In a mouse model, deletion of CXCR3, but not deletion of CXCL9 or CXCL10, in recipients reduces airway obliteration (21). We hypothesized that the chemokine CXCL10 plays a causal role in the pathogenesis of bronchiolitis. In the current study, we measured CXCL10 expression in human BOS and overexpressed chemokine CXCL10 in mice to examine directly the role of CXCL10 in the pathogenesis of bronchiolitis.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Total RNA was isolated from the lungs of patients with progressive BOS undergoing pulmonary retransplantation and tissue trimmed from donor lungs used for transplantation before implantation. The patients included two women and one men who were a mean of 1,490 days from the original transplantation and were a mean 23.5 years of age at the time of retransplantation. The original native diseases that led to the first lung transplantation were cystic fibrosis (n = 2) and congenital heart disease (n = 1). All patients had BOS grade 3 at the time of retransplantation, with a mean FEV1 of 0.85 (22.6% predicted). Histological examination of the explanted transplanted lung confirmed extensive bronchiolitis obliterans (BO) lesions in the absence of any other significant pathology (22, 23). Donor lung tissue had no histopathological abnormalities. The human study received institutional review board approval at Duke University.

Mice

CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice were generated by cloning the mouse CXCL10 cDNA (24) downstream of the rat CC10 promoter (25) and upstream of human growth hormone polyadenylation and intronic sequence (26). Two copies of the chicken β-globin insulator sequence were flanked on both ends of the transgene cassette (27). Transgenic mice were generated in (C57Bl/6 X SJL/J) F2 eggs using standard pronuclear injection and backcrossed onto C57Bl/6 background for more than six generations before use. Several lines of the CXCL10 transgenic mice were generated. Lines 3, 5, and 9 were used in the study. The transgene was genotyped via PCR with the following transgene-specific primers: 5′-ATGAACCCAAGTGCTGCCGTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GAGCTGTTTGTTTTTCTCTCTCC-3′ (reverse). CXCR3-deficient mice (28) were crossed with CXCL10 transgenic mice to generate CXCL10+CXCR3–/– mice. Mice were housed and cared for in a pathogen-free facility at Duke University, and all animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Duke University.

BAL

BAL fluid was collected as described (29) in the online supplement.

ELISA

Levels of mouse chemokine CXCL10 in the BAL were measured with commercial ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

Chemotaxis Assays

Chemotaxis assays (30) are described in the online supplement.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry Analysis

The mouse trachea was cannulated, and the lungs were inflated with 10% formalin. The tissues were fixed overnight, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned for staining with hematoxylin and eosin. Leukocytes in lung sections were stained with specific antibodies against CD3, F4/80, Gr-1, and control IgG (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) and visualized with a Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometric analysis on whole lung single-cell homogenates and BAL was performed as described (29) in the online supplement.

mRNA Analysis

mRNA analysis was performed by PCR as described in the online supplement.

Cell Proliferation Assay

The MTT assay is described in the online supplement.

Statistics

Differences in measured variables between genetically altered mice and the control group, or between treatment groups, were assessed using the Student's t test with JMP software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) or Prism 5 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM where applicable. Statistical difference was accepted at P < 0.05.

Results

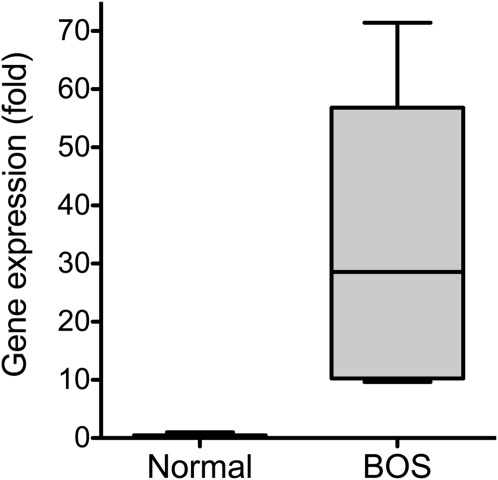

Elevated CXCL10 in Patients with BOS

Previous studies implied that CXCR3–CXCL10 interaction plays a role in acute rejection (19, 31) and airway obliteration (18, 21). When comparing CXCL10 mRNA levels of lung tissues between patients with BOS and control subjects, we found that there was a significant increase in CXCL10 mRNA in patients with BOS (Figure 1). This finding is consistent with previous observations that the elevated levels of CXCR3 chemokines in human BAL fluid were associated with the continuum from acute to chronic rejection (18). These data led us to hypothesize that CXCL10 may play a causal role in the pathogenesis of bronchiolitis.

Figure 1.

Increased CXCL10 mRNA in the lungs of patients with bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS). Total RNA was isolated from the lung tissues of patients with BOS and from control subjects. RT-PCR was used to determine CXCL10 mRNA levels in the lung tissues. Housekeeping gene GusB mRNA levels were used a control (n = 3; P < 0.05).

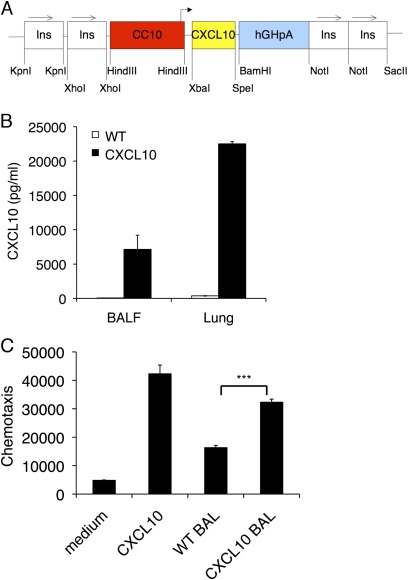

CXCL10 Transgenic Mice Develop Bronchiolitis

We wanted to directly examine the role of CXCL10 in the pathogenesis of bronchiolitis by expressing CXCL10 specifically in the lung. CXCL10-expressing plasmid was constructed where the mouse CXCL10 cDNA was under the control of the rat CC10 promoter, with two copies of the chicken β-globin insulator sequence on both ends of the transgene cassette (Figure 2A). The insulator sequences were used to reduce potential chromosomal position effects (27). The mice were viable and fertile, with normal appearance and no obvious abnormalities. The CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice produced significant amounts of CXCL10 in BAL and lung tissue (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Overexpression of CXCL10 in the lung. (A) Transgenic construct to show that the mouse CXCL10 cDNA was cloned downstream of the rat CC10 promoter and upstream of human growth hormone polyadenylation and intronic sequence. Two copies of the chicken β-globin insulator sequence were flanked on both ends of the transgene. (B) CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice produced a large amount of CXCL10 protein into bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and lung tissue. CXCL10 levels in BAL and lung tissue in 8-week-old transgenic mice and their wild-type (WT) littermates were measure with ELISA (n = 6). (C) CXCL10 in BAL was bioactive. Jurkat cells were plated onto a Boyden chamber. BAL from wild-type or CXCL10 transgenic mice was added to the bottom chamber. Recombinant CXCL10 was used as a positive control. Cells that migrated to the bottom chamber were counted after 4 hours. (n = 3; ***P < 0.001).

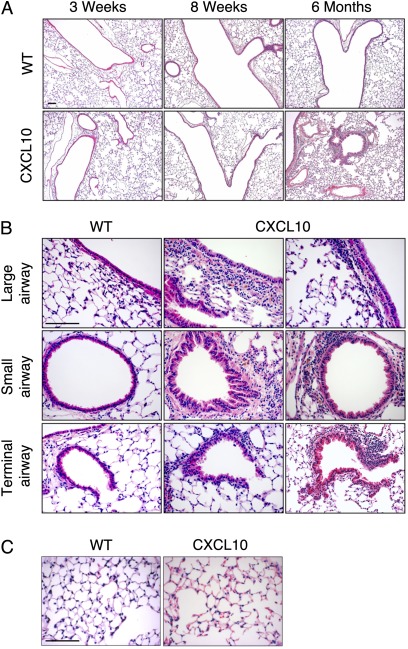

CXCL10 in BAL was biologically active, as demonstrated with a chemotaxis assay (Figure 2C). Histologically, the lungs of CXCL10 transgenic mice were normal in the first 8 weeks of age (Figure 3A). There was no noticeable lung inflammation in the first 2 months. However, airway inflammation was seen in mice after 6 months of age (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Airway inflammation in CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice. (A) Lung micrographs (H&E staining) of CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice and wild-type (WT) littermate control mice at 3 weeks, 8 weeks, or 6 months. Airway inflammation was seen in CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice at 6 months of age. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Lung histology (H&E) of CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice and WT littermate control mice at 6 months. Upper panels, large airways; middle panels, small airways; lower panels, terminal airway. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) Lung histology (H&E) of CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice and WT littermate control mice at 6 months to demonstrate that there was no apparent alveolar inflammation. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Airway Epithelial Hyperplasia

Careful examination of the histology of 6-month-old CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice revealed airway thickening (Figure 3B). Airway epithelial hyperplasia was seen in large and medial airways but more often in small airways (Figure 3B). In some small airways, villus-like structures of epithelial lining were observed (Figure 3B). However, we found no obliterans of airways even in 1-year-old mice. Despite the significant airway inflammation, there was no alveolar inflammation in CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice (Figure 3C). The airway epithelial hyperplasia may have resulted from persistent inflammation or from the effect of CXCL10 on epithelial cell proliferation (32). We confirmed that CXCL10 protein increased proliferation of human airway epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) as determined by MTT assay (medium alone, 0.128 ± 0.0025 in absorbance at 595 nm; CXCL10 at 100 ng/ml, 0.148 ± 0.0032; n = 4; P < 0.01).

There was no change in mucus production. Periodic acid-Schiff staining revealed no difference between CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice and wild-type (WT) littermate control mice (data not shown). There was no evidence of emphysema or fibrosis. Functional study revealed that there was no difference at baseline between CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice and WT littermate control mice (10 wk old) without any challenge. However, reduced airway responsiveness was found in 6-month-old CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice (see Figure E1 in the online supplement). These data suggest that CXCL10-induced airway abnormality affected airway responsiveness.

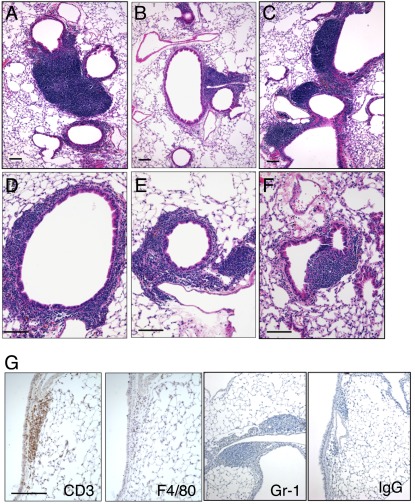

Lymphocyte Infiltration

Perivascular and peribronchiolar infiltration of lymphocytic inflammation was apparent when CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice grew to 6 months and older (Figures 3B and 4A–4F). Inflammatory nodules can be seen around airway (Figures 4A–4F) and blood vessels (Figures 4B, 4C, and 4E). In some severe cases, inflammatory nodules can reach 1 mm in diameter (Figure 4A). Inflammatory infiltration can also be diffused around airway or blood vessels (Figure 3B). The lymphocyte infiltration was very similar to those found in the lungs of transgenic mice expressing IL-6 (25), TNF-α (33), and IL-1β (34).

Figure 4.

Lymphocytic infiltration. (A–F) Lung histology (H&E staining) of CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice at 6 months of age displayed lymphocytic nodules around airways. (G) Lung sections of 6-month-old CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice were stained with specific antibodies against T-cell marker CD3, macrophage marker F4/80, neutrophil marker Gr-1, or control IgG. Scale bar, 100 μm.

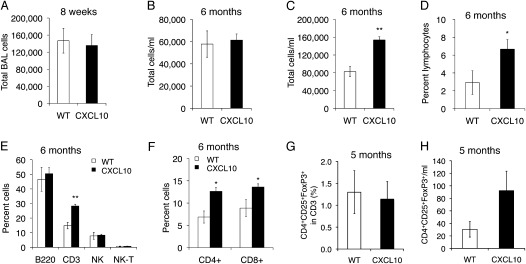

To determine cell types in inflammatory nodules, we stained lung tissue with antibodies specific to CD3 lymphocytes, F4/80 macrophages, or Gr-1 neutrophils and found that CD3 lymphocytes, but not macrophages or neutrophils (Figure 4G), were present in those nodules. We also performed conventional differential cell count and flow cytometry analysis to determine the extent of inflammation in the lungs of CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice. There was no difference in total BAL cells between 8-week-old WT and CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice (Figure 5A), over 90% of the cells were macrophages, and there was no difference in cell differential count (data not shown). Consistent with histological demonstration of the lack of alveolar inflammation, there was no difference in total BAL cells even in older CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice (Figure 5B). However, total lung cells were increased over 6 months of age (Figure 5C), with a significant increase in lymphocytes (Figure 5D). There was no significant difference in macrophages and neutrophils between CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice and WT control mice. Flow cytometry confirmed that there were more CD3+ T lymphocytes in CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice than in WT control mice (Figure 5E). CD4 and CD8 T cells were more abundant in CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice than in WT control mice (Figure 5F). Next, we determined whether CXCL10 expression affects the recruitment of regulatory T cells (Tregs) (CD4+CD25+FoxP3+). CXCL10 did not change the percentage of Tregs in CD3+ cells (Figure 5G), although CXCL10 mice showed a trend toward an increase in Treg number in BAL (Figure 5H).

Figure 5.

Lung inflammation. (A) Total BAL cells from CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice and WT littermate control mice at 8 weeks of age (n = 4; P > 0.05). (B) Total BAL cells of CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice and WT littermate control mice at 6 months of age (n = 4 or 5; P > 0.05). (C) Total mouse lung cells of CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice and WT littermate control mice at 6 months of age (n = 4 or 5; P < 0.01). (D) Lymphocyte percentage of cell differential count of total mouse lung cells of CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice and WT littermate control mice at 6 months of age (n = 4 or 5; P < 0.05). (E, F) Flow cytometry to determine lymphocytes in total mouse lung cells of CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice and WT littermate control mice at 6 months of age (n = 4 or 5; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). (G) Flow cytometric analysis of regulatory T cells (CD4+CD25+FoxP3+) in BAL (n = 3 or 4; P > 0.05). (H) Total Treg cells in BAL (n = 3 or 4; P > 0.05).

CXCL10-Induced Bronchiolitis Depends on the Presence of CXCR3

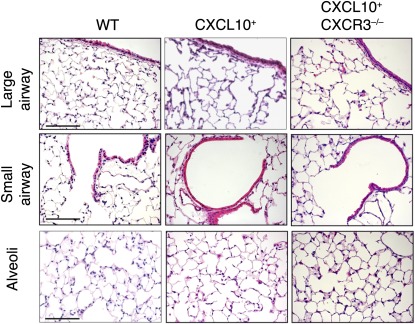

The CXCL10–CXCR3 interaction regulates activated T cells and NK cells. We next determined whether CXCL10-induced airway inflammation and leukocyte infiltration are dependent on its receptor CXCR3. To this end, CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice were crossed with CXCR3-deficient mice to generate CXCL10+CXCR3–/– mice. When CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice were crossed with CXCR3-deficient mice, airway and alveolar structures were normal (Figure 6). There was no airway epithelial hyperplasia, no leukocyte infiltration, no nodules, and no diffuse infiltration (Figure 6). These data suggest that CXCL10-induced bronchiolitis is dependent on the presence of its receptor CXCR3.

Figure 6.

Histology of CXCL10+CXCR3–/– mice. Lung micrographs (H&E) of CXCL10+CXCR3–/– mice, CXCR3–/– mice, and WT littermate control mice at 6 months of age. Normal airway structure (either large or small) was demonstrated in CXCL10+CXCR3–/– mice, and there was no leukocyte infiltration and no apparent alveolar inflammation in CXCL10+CXCR3–/– mice. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that patients with BOS expressed higher levels of CXCL10 mRNA in the lung tissue than control individuals did. We further demonstrated that overexpression of chemokine CXCL10 under control of the CC10 promoter induces bronchiolitis-like inflammation in 6-month-old mice in a CXCR3-dependent manner. Therefore, we provide evidence to demonstrate that the CXCL10 pathway plays a causal role in the development of bronchiolar inflammation.

Induction of CXCL10 occurs in immune-mediated and in non–immune-mediated lung injury (29, 35, 36) and in several models of liver injury and regeneration (12). CXCL10–CXCR3 interactions have been directly implicated in the pathogenesis of immune-mediated tissue damage (18, 21, 28, 36). We and others have shown that, after noninfectious lung injury, CXCL10 is produced and has antifibrotic properties (29, 37–39). Furthermore, CXCR3 ligands are elevated during acute rejection (18, 19, 31, 36) and BOS (18). In addition, CXCL10 is up-regulated during viral bronchiolitis (13, 40). We demonstrated that long-term exposure of CXCL10 alone is able to induce bronchiolitis-like airway inflammation. In adult CCL10–CXCL10 transgenic mice at 6 months of age, airway inflammation is apparent, including airway epithelial cell hyperplasia as well as perivascular and peribronchiolar infiltration of lymphocytes, which resemble the characteristics of chronic bronchiolitis. The airway epithelial hyperplasia may have resulted from persistent airway inflammation, given the fact that there was significant perivascular and peribronchiolar inflammation in CL10–CXCL10 transgenic mice. The hyperplasia may also have resulted from the effect of CXCL10 on epithelial cell proliferation because CXCR3 ligands promote airway epithelial proliferation (32). T-cell infiltration was evident in older CCL10–CXCL10 transgenic mice. These leukocytes were mostly CD3-positive T cells. We did not notice preferential recruitment to CD4 and CD8 because both CD4 and CD8 T cells were increased in the CC10–CXCL10 mouse lungs. These data are consistent with earlier observations that the CXCL10–CXCR3 interaction is critical for the recruitment of T cells to the injury site (9, 11, 41, 42). We also demonstrated that the effect of CXCL10 on airway inflammation required its receptor CXCR3. This is consistent with previous reports that effects of CXCL10 on T-cell recruitment are dependent on CXCR3 (36). The lymphocyte infiltration was similar to that found in transgenic mice expressing the cytokine IL-6 (25), TNF-α (33), and IL-1β (34). Unlike those transgenic mice, CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice have no evidence of emphysema or fibrosis. CXCL10 is induced by IFN-γ (9, 24, 41, 43). CC10–IFN-γ transgenic mice have severe lung inflammation and develop emphysema (44).

Despite significant airway inflammation induced by CXCL10 exposure, the CC10–CXCL10 mice did not spontaneously develop BOS, even in 1-year-old mice. We did not observe measurable airway fibrosis. This may be because inflammation induced by CXCL10 was not severe enough to disrupt basement membrane. The bronchiolar basement membrane was disrupted in lung allograft recipients who had multiple episodes of clinically significant acute cellular rejection and later develop BO (45). More importantly, there is no antigen presentation of mismatched major histocompatibility complex antigens and no production of antibodies to these MHC antigens in the inflammation induced by CXCL10; several reports have suggested that T-cell recognition of alloantigen is the central event that initiates graft rejection (46). Studies have suggested that indirect allorecognition of donor major histocompatibility complex–derived peptides by recipient CD4 T cells contributes to chronic rejection of skin, kidney, liver, and heart allografts (46). Furthermore, CXCL10 plays a role in limiting lung fibrosis by inhibiting angiogenesis (37) or by inhibiting fibroblast migration (38, 39). Thus, CXCL10 may play dual roles in these conditions.

Although allergic airway inflammation such as asthma is generally associated with Th2 activation, Th1 cytokines (e.g., CXCR3 ligands) in asthma have been suggested to play a role. CXCL10 is up-regulated in experimental asthma (47), and overexpression of CXCL10 driven by the bovine keratin 5 on the FVB background showed significantly increased airway hyperreactivity when immunized with ovalbumin (47). However, reduced airway responsiveness was found in CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice without allergy challenge at 6 months of age. This discrepancy may be due to the age of mice, airway structural integrity, and the experimental conditions.

In summary, we successfully generated transgenic mice expressing mouse CXCL10 targeting CC10-expressing cells. Six-month-old CC10–CXCL10 transgenic mice developed bronchiolitis characterized by airway epithelial hyperplasia and T-cell infiltration peribronchiolarly and perivascularly. The airway hyperplasia and T-cell inflammation were dependent on the presence of CXCR3. These data support our hypothesis that chemokine CXCL10 plays a causal role in the pathogenesis of bronchiolitis. However, long-term exposure to chemokine CXCL10 alone was not sufficient to induce BO. Our study provides evidence to support the critical role of chemokine CXCL10 in bronchiolitis but also points to its limited role in the pathogenesis of BO.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. J. Farber of National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIAID, for providing mouse CXCL10 cDNA and Erin Potts and Dr. Michael Foster for assistance with airway resistance experiments.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01-HL77291, RO1-HL060539, and P50-HL084917 (P.W.N.).

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0116OC on December 8, 2011

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.AAP Diagnosis and management of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics 2006;118:1774–1793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Popper HH. Bronchiolitis, an update. Virchows Arch 2000;437:471–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper JD, Billingham M, Egan T, Hertz MI, Higenbottam T, Lynch J, Mauer J, Paradis I, Patterson GA, Smith C, et al. A working formulation for the standardization of nomenclature and for clinical staging of chronic dysfunction in lung allografts. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 1993;12:713–716 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snyder LD, Palmer SM. Immune mechanisms of lung allograft rejection. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2006;27:534–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mukae H, Kadota J, Kohno S, Kusano S, Morikawa T, Matsukura S, Hara K. Increase in activated CD8+ cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in patients with diffuse panbronchiolitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;152:613–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boehler A, Bai XH, Liu M, Cassivi S, Chamberlain D, Slutsky AS, Keshavjee S. Upregulation of T-helper 1 cytokines and chemokine expression in post-transplant airway obliteration. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159:1910–1917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scholma J, Slebos DJ, Boezen HM, van den Berg JW, van der Bij W, de Boer WJ, Koeter GH, Timens W, Kauffman HF, Postma DS. Eosinophilic granulocytes and interleukin-6 level in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid are associated with the development of obliterative bronchiolitis after lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:2221–2225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charo IF, Ransohoff RM. The many roles of chemokines and chemokine receptors in inflammation. N Engl J Med 2006;354:610–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luster AD, Ravetch JV. Biochemical characterization of a gamma interferon-inducible cytokine (IP-10). J Exp Med 1987;166:1084–1097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qin S, Rottman JB, Myers P, Kassam N, Weinblatt M, Loetscher M, Koch AE, Moser B, Mackay CR. The chemokine receptors CXCR3 and CCR5 mark subsets of T cells associated with certain inflammatory reactions. J Clin Invest 1998;101:746–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loetscher M, Gerber B, Loetscher P, Jones SA, Piali L, Clark-Lewis I, Baggiolini M, Moser B. Chemokine receptor specific for IP10 and mig: structure, function, and expression in activated T-lymphocytes. J Exp Med 1996;184:963–969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhai Y, Shen XD, Gao F, Zhao A, Freitas MC, Lassman C, Luster AD, Busuttil RW, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. CXCL10 regulates liver innate immune response against ischemia and reperfusion injury. Hepatology 2008;47:207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller AL, Bowlin TL, Lukacs NW. Respiratory syncytial virus-induced chemokine production: linking viral replication to chemokine production in vitro and in vivo. J Infect Dis 2004;189:1419–1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harvey CE, Post JJ, Palladinetti P, Freeman AJ, Ffrench RA, Kumar RK, Marinos G, Lloyd AR. Expression of the chemokine IP-10 (CXCL10) by hepatocytes in chronic hepatitis C virus infection correlates with histological severity and lobular inflammation. J Leukoc Biol 2003;74:360–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cliffe LJ, Humphreys NE, Lane TE, Potten CS, Booth C, Grencis RK. Accelerated intestinal epithelial cell turnover: a new mechanism of parasite expulsion. Science 2005;308:1463–1465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu MT, Chen BP, Oertel P, Buchmeier MJ, Armstrong D, Hamilton TA, Lane TE. The T cell chemoattractant IFN-inducible protein 10 is essential in host defense against viral-induced neurologic disease. J Immunol 2000;165:2327–2330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dufour JH, Dziejman M, Liu MT, Leung JH, Lane TE, Luster AD. IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10 (IP-10; CXCL10)-deficient mice reveal a role for IP-10 in effector T cell generation and trafficking. J Immunol 2002;168:3195–3204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belperio JA, Keane MP, Burdick MD, Lynch JP, III, Xue YY, Li K, Ross DJ, Strieter RM. Critical role for CXCR3 chemokine biology in the pathogenesis of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. J Immunol 2002;169:1037–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agostini C, Calabrese F, Rea F, Facco M, Tosoni A, Loy M, Binotto G, Valente M, Trentin L, Semenzato G. CXCR3 and its ligand CXCL10 are expressed by inflammatory cells infiltrating lung allografts and mediate chemotaxis of T cells at sites of rejection. Am J Pathol 2001;158:1703–1711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenblum JM, Shimoda N, Schenk AD, Zhang H, Kish DD, Keslar K, Farber JM, Fairchild RL. CXC chemokine ligand (CXCL) 9 and CXCL10 are antagonistic costimulation molecules during the priming of alloreactive T cell effectors. J Immunol 2010;184:3450–3460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medoff BD, Wain JC, Seung E, Jackobek R, Means TK, Ginns LC, Farber JM, Luster AD. CXCR3 and its ligands in a murine model of obliterative bronchiolitis: regulation and function. J Immunol 2006;176:7087–7095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Estenne M, Maurer JR, Boehler A, Egan JJ, Frost A, Hertz M, Mallory GB, Snell GI, Yousem S. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome 2001: an update of the diagnostic criteria. J Heart Lung Transplant 2002;21:297–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maurer JR, Frost AE, Estenne M, Higenbottam T, Glanville AR. International guidelines for the selection of lung transplant candidates. The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation, the American Thoracic Society, the American Society of Transplant Physicians, the European Respiratory Society. J Heart Lung Transplant 1998;17:703–709 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vanguri P, Farber JM. IFN and virus-inducible expression of an immediate early gene, crg-2/IP-10, and a delayed gene, I-A alpha in astrocytes and microglia. J Immunol 1994;152:1411–1418 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DiCosmo BF, Geba GP, Picarella D, Elias JA, Rankin JA, Stripp BR, Whitsett JA, Flavell RA. Airway epithelial cell expression of interleukin-6 in transgenic mice: uncoupling of airway inflammation and bronchial hyperreactivity. J Clin Invest 1994;94:2028–2035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu Z, Ma B, Homer RJ, Zheng T, Elias JA. Use of the tetracycline-controlled transcriptional silencer (tTS) to eliminate transgene leak in inducible overexpression transgenic mice. J Biol Chem 2001;276:25222–25229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bell AC, West AG, Felsenfeld G. The protein CTCF is required for the enhancer blocking activity of vertebrate insulators. Cell 1999;98:387–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hancock WW, Lu B, Gao W, Csizmadia V, Faia K, King JA, Smiley ST, Ling M, Gerard NP, Gerard C. Requirement of the chemokine receptor CXCR3 for acute allograft rejection. J Exp Med 2000;192:1515–1520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang D, Liang J, Hodge J, Lu B, Zhu Z, Yu S, Fan J, Gao Y, Yin Z, Homer R, et al. Regulation of pulmonary fibrosis by chemokine receptor CXCR3. J Clin Invest 2004;114:291–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wright TM, Hoffman RD, Nishijima J, Jakoi L, Snyderman R, Shin HS. Leukocyte chemoattraction by 1,2-diacylglycerol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1988;85:1869–1873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belperio JA, Keane MP, Burdick MD, Lynch JP, III, Zisman DA, Xue YY, Li K, Ardehali A, Ross DJ, Strieter RM. Role of CXCL9/CXCR3 chemokine biology during pathogenesis of acute lung allograft rejection. J Immunol 2003;171:4844–4852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aksoy MO, Yang Y, Ji R, Reddy PJ, Shahabuddin S, Litvin J, Rogers TJ, Kelsen SG. CXCR3 surface expression in human airway epithelial cells: cell cycle dependence and effect on cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006;290:L909–L918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miyazaki Y, Araki K, Vesin C, Garcia I, Kapanci Y, Whitsett JA, Piguet PF, Vassalli P. Expression of a tumor necrosis factor-alpha transgene in murine lung causes lymphocytic and fibrosing alveolitis: a mouse model of progressive pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest 1995;96:250–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lappalainen U, Whitsett JA, Wert SE, Tichelaar JW, Bry K. Interleukin-1beta causes pulmonary inflammation, emphysema, and airway remodeling in the adult murine lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2005;32:311–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dixon AE, Mandac JB, Madtes DK, Martin PJ, Clark JG. Chemokine expression in Th1 cell-induced lung injury: prominence of IFN-gamma-inducible chemokines. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2000;279:L592–L599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hancock WW, Gao W, Csizmadia V, Faia KL, Shemmeri N, Luster AD. Donor-derived IP-10 initiates development of acute allograft rejection. J Exp Med 2001;193:975–980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keane MP, Belperio JA, Arenberg DA, Burdick MD, Xu ZJ, Xue YY, Strieter RM. IFN-gamma-inducible protein-10 attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis via inhibition of angiogenesis. J Immunol 1999;163:5686–5692 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tager AM, Kradin RL, LaCamera P, Bercury SD, Campanella GS, Leary CP, Polosukhin V, Zhao LH, Sakamoto H, Blackwell TS, et al. Inhibition of pulmonary fibrosis by the chemokine IP-10/CXCL10. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004;31:395–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang D, Liang J, Campanella GS, Guo R, Yu S, Xie T, Liu N, Jung Y, Homer R, Meltzer EB, et al. Inhibition of pulmonary fibrosis in mice by CXCL10 requires glycosaminoglycan binding and syndecan-4. J Clin Invest 2010;120:2049–2057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McNamara PS, Flanagan BF, Hart CA, Smyth RL. Production of chemokines in the lungs of infants with severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. J Infect Dis 2005;191:1225–1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gomez-Chiarri M, Hamilton TA, Egido J, Emancipator SN. Expression of IP-10, a lipopolysaccharide- and interferon-gamma-inducible protein, in murine mesangial cells in culture. Am J Pathol 1993;142:433–439 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gattass CR, King LB, Luster AD, Ashwell JD. Constitutive expression of interferon gamma-inducible protein 10 in lymphoid organs and inducible expression in T cells and thymocytes. J Exp Med 1994;179:1373–1378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amichay D, Gazzinelli RT, Karupiah G, Moench TR, Sher A, Farber JM. Genes for chemokines MuMig and Crg-2 are induced in protozoan and viral infections in response to IFN-gamma with patterns of tissue expression that suggest nonredundant roles in vivo. J Immunol 1996;157:4511–4520 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Z, Zheng T, Zhu Z, Homer RJ, Riese RJ, Chapman HA, Jr, Shapiro SD, Elias JA. Interferon gamma induction of pulmonary emphysema in the adult murine lung. J Exp Med 2000;192:1587–1600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siddiqui MT, Garrity ER, Martinez R, Husain AN. Bronchiolar basement membrane changes associated with bronchiolitis obliterans in lung allografts: a retrospective study of serial transbronchial biopsies with immunohistochemistry [corrected]. Mod Pathol 1996;9:320–328 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sherman LA, Chattopadhyay S. The molecular basis of allorecognition. Annu Rev Immunol 1993;11:385–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Medoff BD, Sauty A, Tager AM, Maclean JA, Smith RN, Mathew A, Dufour JH, Luster AD. IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10 (CXCL10) contributes to airway hyperreactivity and airway inflammation in a mouse model of asthma. J Immunol 2002;168:5278–5286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.