Abstract

Rationale: Tuberculosis kills more than 1.5 million people per year, and standard treatment has remained unchanged for more than 30 years. Tuberculosis (TB) drives matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity to cause immunopathology. In advanced HIV infection, tissue destruction is reduced, but underlying mechanisms are poorly defined and no current antituberculous therapy reduces host tissue damage.

Objectives: To investigate MMP activity in patients with TB with and without HIV coinfection and to determine the potential of doxycycline to inhibit MMPs and decrease pathology.

Methods: Concentrations of MMPs and cytokines were analyzed by Luminex array in a prospectively recruited cohort of patients. Modulation of MMP secretion and Mycobacterium tuberculosis growth by doxycycline was studied in primary human cells and TB-infected guinea pigs.

Measurements and Main Results: HIV coinfection decreased MMP concentrations in induced sputum of patients with TB. MMPs correlated with clinical markers of tissue damage, further implicating dysregulated protease activity in TB-driven pathology. In contrast, cytokine concentrations were no different. Doxycycline, a licensed MMP inhibitor, suppressed TB-dependent MMP-1 and -9 secretion from primary human macrophages and epithelial cells by inhibiting promoter activation. In the guinea pig model, doxycycline reduced lung TB colony forming units after 8 weeks in a dose-dependent manner compared with untreated animals, and in vitro doxycycline inhibited mycobacterial proliferation.

Conclusions: HIV coinfection in patients with TB reduces concentrations of immunopathogenic MMPs. Doxycycline decreases MMP activity in a cellular model and suppresses mycobacterial growth in vitro and in guinea pigs. Adjunctive doxycycline therapy may reduce morbidity and mortality in TB.

Keywords: lung, mycobacteria, immunopathology, protease inhibitors

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Tuberculosis (TB) causes extensive immunopathology resulting in morbidity and mortality, but this tissue destruction is reduced in advanced HIV infection. The underlying mechanisms of this divergent pathology are poorly understood.

What This Study Adds to the Field

We show that matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) concentrations are suppressed in HIV-TB coinfection and correlate with immunopathology, demonstrating MMPs are final effectors of matrix destruction in TB. Doxycycline, a licensed MMP inhibitor, suppresses TB-driven MMP secretion and inhibits mycobacterial growth. Adjunctive doxycycline may improve outcomes in patients with TB.

Tuberculosis (TB) continues to kill more than 1.5 million people a year (1). Standard treatment for TB has remained unchanged for more than 30 years (2), and multidrug- and extensively drug–resistant strains are progressively emerging (3, 4). Mortality rates remain high among patients even after they have commenced TB treatment (5, 6). A characteristic hallmark of TB is tissue destruction, causing morbidity, mortality, and transmission of infection. However, the mediators of this immunopathology are incompletely understood (7, 8), preventing the design of rational therapies to reduce immune-mediated host damage and improve outcomes in TB.

TB is primarily a disease of the lung (9, 10). In advanced HIV infection, with severely reduced CD4 cell counts, TB infection is common, but there is reduced tissue destruction and cavitation rarely occurs (11). The underlying cause of divergent pathology in HIV-TB coinfection is poorly defined, and greater understanding of this tissue destruction may identify novel therapeutic approaches to limit morbidity and mortality. The biochemistry of the lung extracellular matrix predicts that matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) will be the dominant proteases driving lung matrix destruction in TB (12). We have shown that MMP-1 is a key collagenase up-regulated in patients with TB (13, 14), and MMP-1 expression is suppressed by p-amino salicylic acid, an antituberculous agent used for 70 years but with an incompletely understood mechanism of action (15). In the zebrafish model, MMP-9 regulates monocyte recruitment to the granuloma (16), indicating that MMPs both modulate the immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) and drive pathology (17). MMPs are a family of zinc-dependent proteases that collectively can degrade all components of the extracellular matrix (18). The only pharmacological agent licensed as an MMP inhibitor in the United States is doxycycline, a tetracycline antibiotic, which is used in periodontal disease at subantimicrobial doses to suppress collagenase activity (19).

In this study, we first investigated the hypothesis that reduced lung tissue destruction in advanced HIV results from suppressed MMP activity, by prospectively recruiting a cohort of HIV-infected and -uninfected South African patients and recording a detailed clinical phenotype. We investigated MMPs, cytokines, and chemokines in respiratory secretions to measure mediators of immunopathology at the site of disease. MMPs were suppressed in HIV-TB coinfection and correlated closely with clinical parameters of TB-driven lung destruction. In contrast, cytokines and chemokines were not suppressed in advanced HIV-TB infection, further implicating MMP activity as the final effector of immune-mediated tissue damage. Next, we investigated the MMP inhibitor doxycycline in human cells and examined the effects of doxycycline on MMP activity, tissue damage, and mycobacterial growth in the guinea pig model of TB.

Methods

Full methods are provided in the online supplement

Patient Recruitment

The study was approved by the University of Cape Town Research Ethics Committee (REC REF 509/2009). Participants were recruited at Ubuntu HIV/TB clinic and GF Jooste Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained, HIV testing was offered, and chest radiographs were performed as per routine practice. Case definitions and cohort characteristics are provided in Tables E1 and E2 in the online supplement.

Sample Collection and Processing

Sputum induction was performed with 5% saline nebulized in 5-minute cycles, up to 20 minutes as tolerated. Sputum was expectorated into two to three sterile collection containers. Induced sputum was kept on ice and processed within 2 hours. Sputum samples were sent for microbiological examination (smear microscopy and culture). For Luminex analysis, mucolysis was performed by adding 0.1% dithiothreitol (Merck, Feltham, UK) and agitating for 20 minutes. Samples were frozen at −80°C. Samples were then defrosted, centrifuged, and sterile filtered through a 0.2-μm Durapore membrane (Millipore, Watford, UK) (20).

Clinical Scoring System

A modified chest radiograph scoring system was used (Figure E1) (21). Cavities were recorded as present or absent. Sputum acid-fast bacillus (AFB) score was analyzed with the score of: 0 = negative, 1 = scanty, 2 = +, 4 = ++, and 6 = +++.

Luminex Assay

Samples were analyzed on the Luminex 200 platform using MMP beads (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK) and cytokines (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) and analyzed as per manufacturer's instructions. Total protein was quantified by Bradford assay (Biorad, Hemel Hempstead, UK).

Cell Culture Experiments

Monocyte-derived primary human macrophages were infected with Mtb H37Rv as described (15), and this strain was used in all cellular experiments. Primary human bronchial epithelial cells (Lonza, Slough, UK) were cultured and stimulated with conditioned media from Mtb-infected monocytes (CoMtb) and A549 cells transiently transfected as described (22).

Gelatin Zymography

Gelatin zymography was performed as previously described (13).

Guinea Pig Aerosol Challenge with M. tuberculosis, Doxycycline Administration, and Necropsy

Guinea pig experimental work was conducted according to U.K. Home Office legislation and was approved by the local ethical committee. Outbred female Dunkin Hartley guinea pigs were aerosol challenged with M. tuberculosis (23). For the first 2 weeks, all guinea pigs were given fruit puree containing 0.1 g/ml probiotic (Protexin, Somerset, UK). From Week 3, guinea pigs in the drug treatment group received puree and probiotic containing doxycycline at either 5 or 20 mg/kg.

At 10 weeks, guinea pigs were killed. The right lung was formalin inflated. The upper left lung lobe and spleen sections were placed into RNAlater (Qiagen, Crawley, UK). The remaining spleen and lung tissue were placed into sterile tubes for storage at −20°C for bacteriological analysis. Tissues were homogenized using a rotating blade macerator. Viable counts were performed plating serial dilutions onto Middlebrook 7H11 agar (BioMerieux, Basingstoke, UK). Hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides were digitized on a Hamamatsu Nanozoomer and lung infiltration measured by Hamamatsu NPD virtual slide viewer software.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with Graphpad Prism 5. Clinical data were analyzed by the two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test and by Spearman correlation. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

MMP-1, -2, -3, and -8 Are Increased in Pulmonary TB in HIV-Positive and -Negative Patients

We prospectively recruited a cohort of South African patients under investigation for probable TB infection who were either HIV negative or HIV positive and profiled MMPs, cytokines, and chemokines (demographic data, Table 1; case definitions, Tables E1 and E2). The TB and control groups were well matched for age, HIV prevalence, and median CD4 cell count, although there were more women in the control group, which likely reflects differences in health-seeking behavior between sexes (24). Biomass fuel exposure in this community is very low, with paraffin being the primary fuel used for cooking. Sputum samples from control patients were culture negative for Mtb at 42 days, excluding smear-negative infection in symptomatic HIV-negative patients. The patients with TB, including those coinfected with HIV, had significantly more symptoms, such as cough, fever, and night sweats, a lower body mass index, and an abnormal respiratory examination, consistent with their final diagnosis of pulmonary TB. There was no significant difference in symptom duration between patients with and without cavities.

TABLE 1.

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF PATIENT COHORT

| Control |

TB |

||||

| Patient Characteristics | N | % | n | % | P Value* |

| Total no. patients | 21 | 23 | |||

| Female | 16 | 76.2 | 10 | 43.5 | 0.0358 |

| HIV positive | 12 | 57.1 | 15 | 65.2 | 0.758 |

| Median CD4 (range) | 267 (153–437) | n/a | 162 (9–607) | n/a | 0.060 |

| Median age (range), yr | 29 (21–45) | n/a | 32 (20–53) | n/a | 0.724 |

| Occupation, employed/unemployed/other | 6/13/2 | 28.6/61.9/9.52 | 5/14/4 | 23.8/60.9/17.35 | 0.732/1.00/0.663 |

| Smoking history, current/ex-/non/unknown | 3/2/16/0 | 14.3/9.52/57.1/0 | 7/3/12/1 | 30.4/13/ 52.2/4.35 | 0.287/1.00/0.125/1.000 |

| BCG history, vaccinated/not vaccinated/unknown | 11/3/7 | 47.6/14.3/33.3 | 7/8/8 | 30.4/34.8/34.8 | 0.287/0.169/1.000 |

| Symptoms | |||||

| Any | 8 | 38.1 | 23 | 100 | <0.0001 |

| Fever | 3 | 14.3 | 13 | 56.5 | 0.005 |

| Cough | 8 | 38.1 | 21 | 91.3 | 0.0003 |

| Hemoptysis | 0 | 0 | 4 | 17.4 | 0.109 |

| Night sweats | 3 | 14.3 | 17 | 73.9 | <0.0001 |

| Weight loss | 5 | 23.8 | 20 | 87.0 | <0.0001 |

| Breathlessness | 2 | 9.52 | 7 | 30.4 | 0.136 |

| Pleuritic pain | 3 | 14.3 | 13 | 56.5 | 0.005 |

| Anorexia | 1 | 4.76 | 4 | 17.4 | 0.348 |

| Median symptom duration (range) | 28 (21–1000) | n/a | 42 (14–365) | n/a | 0.625 |

| Previous history of TB | 5 | 23.8 | 8 | 34.8 | 0.517 |

| Examination | |||||

| Median BMI (range) | 27.9 (19.38–39.35) | n/a | 20.1 (16.51–40.48) | n/a | 0.0033 |

| Temperature > 37.5°C | 0 | 0 | 3 | 13 | 0.234 |

| Abnormal respiratory system | 6 | 28.6 | 17 | 73.9 | 0.0059 |

Definition of abbreviations: BCG = bacillus Calmette-Guérin; BMI = body mass index; n/a = not applicable; TB = tuberculosis.

Fisher exact test (two-tailed) except in cases of continuous variables, in which Mann-Whitney U test applied.

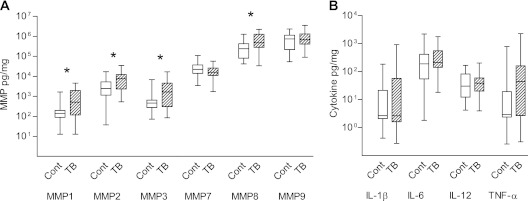

Concentrations of MMP-1, -2, -3, and -8 were increased in the induced sputum of patients with TB compared with control subjects when analyzed irrespective of HIV status (Figure 1A; P = 0.013, 0.040, 0.019, and 0.039 respectively). Median values, range, and 25th and 75th centiles are provided in Table E3. MMP-12 was not significantly different between the groups, and MMP-13 concentrations were mainly below the level of sensitivity of the assay. When analysis was performed on MMP concentrations in induced sputum uncorrected for total protein, MMP-1, -2, -3, and -8 were similarly increased in TB (Table E4).

Figure 1.

Multiple matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are up-regulated in HIV-positive and -negative patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis (TB). Induced sputum samples were collected prospectively from patients in Cape Town. MMP, cytokine, and chemokine concentrations were measured by Luminex multiplex array and total protein by Bradford assay. Analytes are expressed as pg/mg protein. (A) MMP-1, -2, -3, and -8 are significantly elevated in patients with pulmonary TB compared with control subjects without TB (medians and interquartile range, Table E3). (B) IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-12 were not elevated in patients with pulmonary TB, whereas tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α showed a nonsignificant trend toward increase. The other 26 cytokines analyzed were either not detectable or not significantly different between groups (Table E5). Differences analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test are shown, *P < 0.05. Each box outline represents the 25th and 75th percentiles, the central line the median value, and the whiskers minimum and maximum values. Cont = control.

Inflammatory mediators measured by Luminex multiplex array were cytokines (IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, IL-15, IL-17, tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α, IFN-α, IFN-γ, IL-1RA, IL-2R), chemokines (IL-8, macrophage inflammatory protein [MIP]-1α, MIP-1β, Eotaxin, monokine induced by interferon-γ [MIG], monocyte chemotactic protein [MCP]-1, regulated upon activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted [RANTES], IFN-inducible protein of 10 kDa [IP-10]), and growth factors (epidermal [EGF], hepatocyte [HGF], vascular endothelial [VEGF], and fibroblast [FGF] growth factors and granulocyte [G-CSF] and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating [GM-CSF] factors). No cytokine or chemokine was significantly elevated in patients with TB, including those with HIV coinfection after normalization to total protein. Median TNF-α concentrations were elevated, but this was not statistically significant (P = 0.082, Figure 1B). Concentrations of cytokines and chemokines are provided in Table E5.

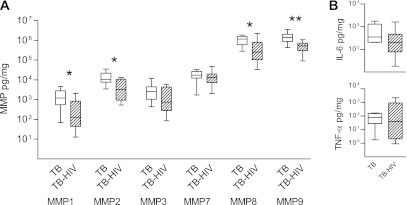

MMP-1 Concentrations Are Lower in Patients with Advanced HIV Infection

Patients with advanced HIV infection with a CD4 cell count below 200 rarely develop cavitary lung disease, even though TB is more common as CD4 cell count falls (11). Therefore, we investigated MMP and cytokine concentrations in patients with TB who were either HIV positive with a CD4 count of less than 200 or HIV negative to determine mediators driving immunopathology. MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-8, and MMP-9 were significantly lower in the induced sputum from patients with advanced HIV-TB coinfection than HIV-negative patients with TB (Figure 2A; P = 0.019, 0.038, 0.038, and 0.003, respectively). Median MMP-1 concentrations in HIV-negative patients with TB were 1,213.0 pg/mg, whereas in patients with TB with advanced HIV infection they were 129.1 pg/mg. No significant differences in proinflammatory cytokines or chemokines were demonstrated between TB and HIV-TB coinfection (Figure 2B and data not shown).

Figure 2.

Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) concentrations are suppressed in patients with tuberculosis (TB) with advanced HIV infection. MMP concentrations were analyzed in patients with pulmonary TB who were either HIV negative or HIV positive with a CD4 cell count below 200. (A) MMP-1, -2, -8, and -9 were significantly lower in the induced sputum of patients with TB with advanced immunocompromise due to HIV infection. (B) In contrast, no cytokine concentration significantly differed between these groups. n = 8 in each group. Differences analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test are shown. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Each box outline represents the 25th and 75th percentiles, the central line the median value, and the whiskers minimum and maximum values.

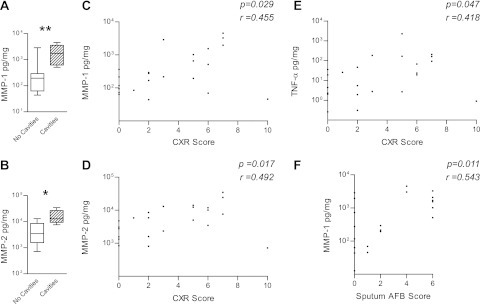

MMP-1 Correlates Most Closely with Markers of Immunopathology

Next, we analyzed associations between induced sputum MMPs, cytokines, and chemokines and parameters of lung tissue destruction. First, we compared sputum MMP and cytokine concentrations in patients with cavitary lung disease to those with noncavitary pulmonary TB. Cavities were present in 80% of TB-infected HIV-negative patients who had chest radiographs, compared with 17% of HIV-TB coinfected patients. MMP-1 and -2 were significantly elevated in patients with lung cavities compared with those without cavities (Figures 3A and 3B). No other MMPs were significantly different between groups. Next, we analyzed MMP concentrations according to the degree of chest radiograph infiltration. MMP-1 and MMP-2 concentrations positively correlated with the extent of lung infiltration (Figures 3C and 3D). One patient with miliary TB had radiographic abnormalities in all zones but low sputum MMPs, consistent with infection limited to the lung interstitium. TNF-α concentrations also correlated with the extent of pulmonary involvement scored on chest radiographs (Figure 3E).

Figure 3.

Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) concentrations correlate with pulmonary cavitation, lung infiltration, and acid-fast bacillus (AFB) smear status. MMP-1 and -2 concentrations were significantly elevated in patients with tuberculosis (TB) with cavitary pulmonary disease compared with patients with TB with noncavitary disease (A, B). The degree of chest radiograph consolidation was scored on a scale of 0–10 (radiograph scoring system, Figure E1) and correlated with MMP-1 (C), MMP-2 (D), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α concentrations (E), but no other MMPs or cytokines. MMP-1 concentrations in induced sputum correlate with the mycobacterial load (F). In contrast, no other analyte studied positively correlated with sputum AFB score. Spearman correlation coefficient and P values are shown. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by Mann-Whitney U test. CXR = chest X-ray.

Finally, we compared MMPs with the sputum AFB score. The sputum AFB score can vary between samples, so the highest score for each patient was recorded. Despite the potential for this variability to obscure a true difference, MMP-1 associated with increased mycobacterial load in the sputum (Figure 3F), demonstrating that increased mycobacterial loads correlated most closely with increased collagenase concentrations in respiratory sections. In parallel analyses, cytokine and chemokine concentrations were compared with clinical parameters, but no associations other than TNF-α and radiographic score were found.

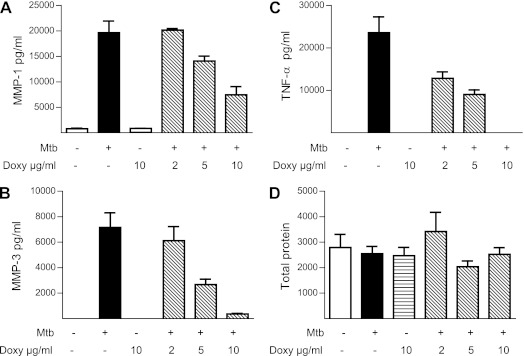

Doxycycline Inhibits MMP Secretion by Mtb-infected Human Macrophages

The reduced MMP concentrations in patients with HIV-TB coinfection and the association between MMPs and markers of immunopathology implicate excessive MMP activity in driving tissue destruction in TB. Doxycycline is an antibiotic with broad spectrum MMP inhibitory activity and is the only licensed MMP inhibitor in the United States (25). Therefore, we examined whether doxycycline modulated MMP secretion driven by Mtb. Doxycycline suppressed MMP-1 and MMP-3 secretion by Mtb-infected primary human macrophages at 72 hours in a dose-dependent manner (Figures 4A and 4B). In addition, doxycycline suppressed TNF-α secretion by macrophages (Figure 4C). This effect was not due to suppression of total protein synthesis, because protein accumulation in the cell culture supernatants was the same in each group (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Doxycycline inhibits matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α secretion from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb)-infected macrophages. Primary human monocyte-derived macrophages were preincubated with doxycycline at a range of 2–10 μg/ml for 2 hours and then infected with Mtb at a multiplicity of infection of 1. Doxycycline suppressed MMP-1 (A) and MMP-3 (B) secretion at 72 hours in a dose-dependent manner. (C) Secretion of TNF-α was similarly suppressed by doxycycline. (D) Total protein secreted by macrophages analyzed by Bradford assay was not suppressed by doxycycline. Mean values ± SEM are shown and are representative of experiments performed in triplicate on at least two occasions. Doxy = doxycycline.

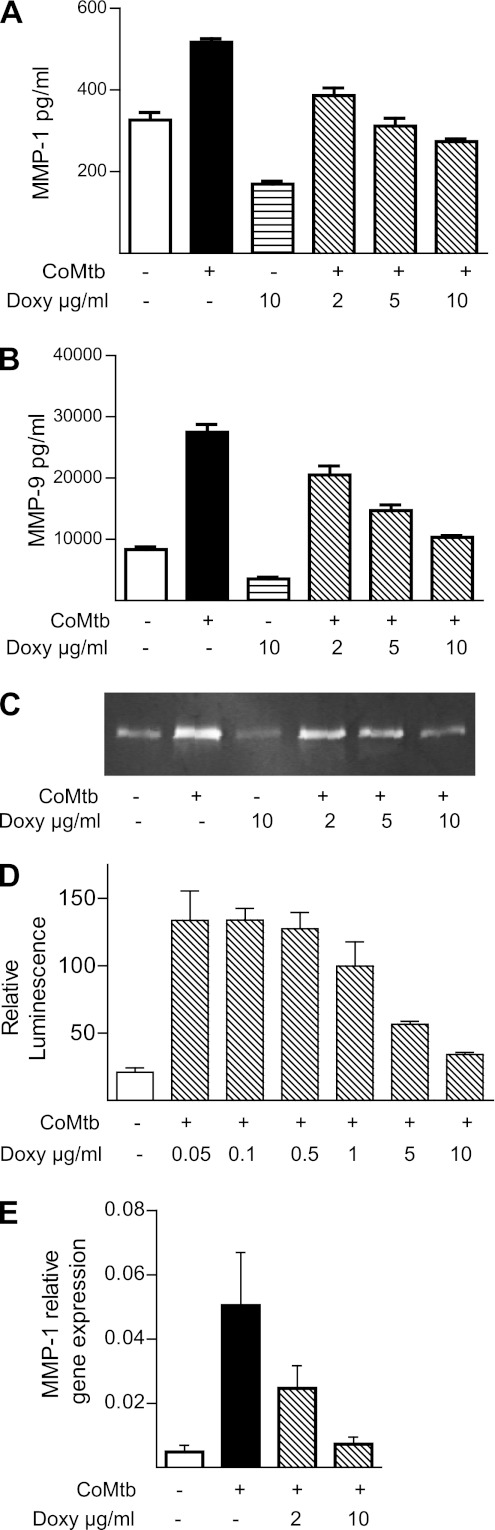

Doxycycline Suppresses Epithelial Cell MMP Secretion by Inhibiting Promoter Activity

Stromal cells also secrete MMPs in TB (16, 22, 26), so we investigated the effect of doxycycline on MMP gene expression and secretion by human respiratory epithelial cells. Doxycycline suppressed MMP-1 and MMP-9 secretion from primary human bronchial epithelial cells stimulated by conditioned media from Mtb-infected monocytes (CoMtb) (Figures 5A and 5B). Doxycycline reduced total MMP-9 activity analyzed by gelatin zymography in the cell culture supernatants, consistent with the analysis of immunoreactive protein by Luminex (Figure 5C). Total protein in cell culture supernatants was no different between groups by Bradford analysis (data not shown). To further investigate the mechanism of action of doxycycline, we transiently transfected A549 cells with the full-length MMP-1 promoter. CoMtb up-regulated MMP-1 promoter activity, which was suppressed by doxycycline (Figure 5D), demonstrating that doxycycline inhibits MMP-1 secretion by suppressing promoter activation. Furthermore, doxycycline suppressed MMP-1 mRNA accumulation in A549 cells at 24 hours (Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

Doxycycline suppresses epithelial cell matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) secretion by inhibiting promoter activation. (A) Primary human epithelial cells were stimulated with conditioned media from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb)-infected primary monocytes (CoMtb) after preincubation with doxycycline for 2 hours. MMP-1 secretion driven by CoMtb was suppressed by doxycycline in a dose-dependent manner analyzed by Luminex array. (B) Similarly, MMP-9 secretion by primary epithelial cells was suppressed by doxycycline. (C) Reduced immunoreactive MMP-9 resulted in reduced proteolytic activity analyzed by gelatin zymography. (D) Doxycycline suppresses CoMtb-driven MMP-1 promoter activity at 24 hours in A549 cells transiently transfected with the full-length promoter. (E) Doxycycline suppresses MMP-1 gene expression normalized to 18S gene expression in a dose-dependent manner at 24 hours. Mean values ± SEM are shown and are representative of experiments performed in triplicate on at least two occasions. Doxy = doxycycline.

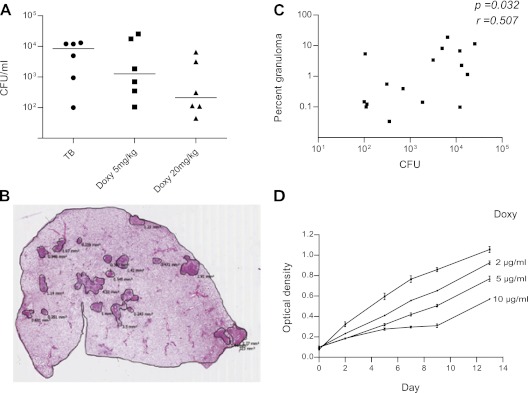

Doxycycline Reduces Mtb Growth in the Guinea Pig Model of TB

To investigate the effect of doxycycline on the pathology of TB infection in a model system, we studied guinea pigs infected with Mtb by aerosol. Guinea pigs develop extensive caseating granulomas when infected with Mtb and succumb to a primary progressive disease. Three groups of six guinea pigs were infected, and after 2 weeks groups were treated with doxycycline monotherapy at either 5 mg/kg or 20 mg/kg. Doxycycline suppressed lung cfu at 10 weeks in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6A). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis of MMP -1, -8, -9, -13, and TNF-α expression in lung tissue did not show any difference between uninfected guinea pigs and TB-infected animals, nor between TB-infected guinea pigs and doxycycline-treated guinea pigs. Next, we determined the area of granulomatous involvement in each lung by digital image analysis (Figure 6B). Lung cfu correlated positively with the percentage granulomatous infiltration of the lung (Figure 6C), but no independent effect of doxycycline could be identified, suggesting that doxycycline is acting directly to limit mycobacterial proliferation in the guinea pig model rather than on MMP activity to alter immunopathology.

Figure 6.

Doxycycline suppresses Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) proliferation in guinea pigs and in broth culture. Outbred Hartley-Dunkin guinea pigs were infected with 10–20 cfu Mtb by aerosol. In treatment groups, oral administration of doxycycline at 5 mg/kg or 20 mg/kg was initiated 2 weeks after infection and continued until the experiment was terminated at 10 weeks. (A) Doxycycline suppressed Mtb colony counts in the lungs in a dose-dependent manner. Horizontal lines represent the median value. (B) Total area of granulomatous lung involvement was measured for each animal by digital image analysis and expressed as the percentage of total area (representative analysis section shown). Eight noncontiguous sections from the right lung of each infected guinea pig were analyzed. (C) The percentage granulomatous infiltration in infected lung correlated with the total cfu by Spearman analysis. (D) Doxycycline slows Mtb growth in 7H9 broth in a dose-dependent manner, with a significantly reduced growth demonstrated from 2 days and persisting at 14 days of culture. Mean ± SEM of three culture samples is shown and is representative of three separate experiments. Doxy = doxycycline; TB = tuberculosis.

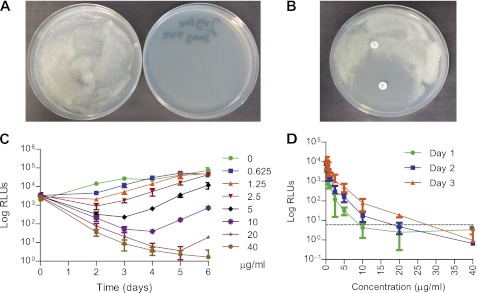

Doxycycline Is Bacteriostatic to Mtb Growth with a Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of 2.5 μg/ml

To investigate whether doxycycline was having a direct antibiotic effect on Mtb, we studied bacterial growth over a 12-day period in the presence or absence of doxycycline in 7H9 culture broth. Doxycycline significantly suppressed mycobacterial growth as analyzed by optical density from Day 2 (Figure 6D). Next, we impregnated 7H11 agar plates with doxycycline 2 μg/ml and demonstrated complete inhibition of Mtb growth after 2 weeks (Figure 7A). Similarly, in a disc diffusion assay, doxycycline prevented Mtb growth, whereas penicillin did not (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Doxycycline has a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 2.5 μg/ml against Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). (A) 7H11 agar impregnated with doxycycline 2 μg/ml completely suppresses growth of Mtb at 14 days. (B) A 30-μg doxycycline disc prevents Mtb growth on 7H11 agar, whereas a penicillin disc has no effect. (C) Doxycycline suppresses bioluminescence from H37Rv in culture in a dose-dependent manner, with a 1 log suppression of luminescence at 2 days with 2.5 μg/ml. Data shown are the mean and SD from three independent experiments. (D) To determine the minimum bactericidal concentration, aliquots from the MIC experiment were diluted into antibiotic-free 7H11 broth and bioluminescence monitored over 3 days. Doxycycline 40 μg/ml completely suppressed luminescence, demonstrating that this was the bactericidal concentration. Dashed line = background luminescence. RLU = relative light units.

Finally, to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), we cultured bioluminescent Mtb with increasing concentrations of doxycycline and monitored bioluminescence over time, as previously described (27). Using this method, the MIC is defined as the lowest antibiotic concentration causing a 1 log drop in relative light units after 2 to 3 days of incubation, compared with the luminescence in the antibiotic-free controls (27). Doxycycline caused a dose dependent reduction in luminescence (Figure 7C) with an MIC of 2.5 μg/ml. Similar results were obtained with the more traditional resazurin reduction assay after 7 days of incubation (MIC = 5 μg/ml). To determine the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC), 5-μl aliquots from the MIC experiment were diluted in 195 μl antibiotic-free 7H9 broth, and luminescence was monitored over 3 days (Figure 7D). The MBC, defined as the lowest antibiotic concentration with a luminescence less than or equal to the background, was found to be 40 μg/ml doxycycline, giving an MBC/MIC ratio of 16 and thereby confirming that doxycycline is bacteriostatic to Mtb growth.

Discussion

We prospectively recruited a patient cohort of HIV-infected and -uninfected patients and performed detailed immunological analysis of specimens from the site of TB infection to investigate the hypothesis that reduced tissue destruction in HIV-TB coinfection may be due to relatively decreased MMP activity. In advanced HIV disease, in which lung destruction such as cavitation is rarely seen (11), MMP concentrations were suppressed. MMPs consistently associated with lung pathology, whereas cytokine and chemokine concentrations did not, further implicating these proteases in TB-related matrix destruction. Statistically significant differences between groups emerged despite the relatively small sample size, which would be predicted to obscure minor differences. Next, we investigated whether doxycycline, a licensed MMP inhibitor of proven safety in humans, might inhibit MMP activity and reduce tissue damage in TB. Doxycycline suppressed Mtb-driven MMP secretion in primary human monocytes and respiratory epithelial cells. In guinea pigs, doxycycline did not modulate MMP activity but decreased mycobacterial replication, a finding confirmed in multiple assays of Mtb growth. Together, these findings suggest that adjunctive doxycycline therapy may improve outcomes in TB by reducing excessive protease activity and limiting mycobacterial growth.

MMP-1, -2, -3, and -8 were increased in patients with TB. We previously demonstrated increased MMP-1 and -3 concentrations in patients with TB compared with patients with respiratory symptoms (14), and again these MMPs were the most significantly elevated. The greater range of TB-related MMPs identified here may result from comparing patients with TB to healthy control subjects. MMP-1, -2, -8, and -9 were suppressed in advanced HIV infection. MMP-1 is emerging as a dominant collagenase in driving immunopathology in TB (14), whereas MMP-9 regulates monocyte recruitment to mycobacterial granulomas (16). MMP-8 concentrations were also suppressed in HIV, and because neutrophils secrete both MMP-8 and -9 (28), this suggests that reduced neutrophil recruitment to the lung may occur in advanced HIV infection.

MMP-1 associated closely with parameters of immunopathology, such as chest radiograph infiltration, cavitation, and sputum AFB score, supporting the hypothesis that MMP-1 plays a critical role in TB immunopathogenesis (17). Chest radiograph scoring is a relatively insensitive indicator of pulmonary inflammation (21), because it only measures area of lung involvement but not density of consolidation, and yet a positive association with MMP-1 concentration was shown. In support of a central role for MMP-1 in TB pathogenesis, MMP-1 polymorphisms have been linked to the risk of developing TB (29).

These clinical data further implicate MMPs as the final effectors of matrix destruction in TB. Therefore, MMPs may represent a potential therapeutic target to limit morbidity and mortality. Doxycycline is a licensed MMP inhibitor in the United States used to treat periodontal disease (30) and has been proposed as an agent to limit pathology in other infectious and inflammatory diseases (31–34). Doxycycline suppressed multiple MMPs in cellular models of Mtb infection. In primary macrophages, MMP suppression may have been secondary to both inhibiting Mtb growth and reducing MMP expression, but in normal human bronchial epithelial and A549 cells the effect of doxycycline on MMP secretion, promoter activity, and mRNA accumulation was direct, because the CoMtb stimulus contained no live mycobacteria. Doxycycline is also an inhibitor of MMP activity (25). Consequently, doxycycline may reduce pathology in human TB by effects on both MMP gene transcription and activity. Doxycycline is used in periodontal disease at a low dose of 20 mg twice daily (30) and so may also be effective at suppressing immunopathologic MMPs in TB with this regime. Doxycycline also suppressed TNF-α secretion, a key cytokine in the immune response to TB (7). TNF-α drives stromal cell MMP secretion via intercellular networks (22, 26, 35) and may also drive cachexia in TB (36), so doxycycline may have multiple immunomodulatory effects.

Previous studies of MMP inhibition in TB have used the mouse model (37, 38), but the mouse does not develop immunopathology similar to man (39) and does not express a functional ortholog of human MMP-1 in the lung (40). We investigated doxycycline in the guinea pig model of TB, which develops extensive caseous necrosis, although not cavitation (41). We did not demonstrate increased MMP gene expression in Mtb-infected guinea pigs, unlike in human TB infection (42). This may reflect a delayed global reprogramming of granuloma gene expression that has recently been identified in the primate model of TB (43). In addition, because no MMP-1 up-regulation was demonstrated in infected animals, and guinea pigs very rarely cavitate when infected with TB, this model may not be optimal to study MMP-modulating effects of doxycycline. Studies in a cavitary model, such as the rabbit (44), are likely to be necessary.

Unexpectedly, doxycycline monotherapy reduced mycobacterial growth in vivo, suggesting that in the guinea pig model it was having a direct antimicrobial effect. Doxycycline is not usually considered an antimycobacterial agent, but has occasionally been used in the treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial infection (45). Doxycycline was introduced in 1967, the same year as rifampicin, so potential antimycobacterial activity may have been overlooked. Doxycycline suppressed Mtb growth in broth culture in a dose-dependent manner, consistent with previous reports (46–48), and we identified an MIC of 2.5 μg/ml with a bacteriostatic activity. The peak concentration of doxycycline in serum is 3.2 μg/ml (49), so doxycycline may achieve sufficient concentration in the lung interstitium to reduce Mtb growth in patients in addition to modulating MMP expression and activity.

In summary, MMP concentrations are suppressed in advanced HIV-TB coinfection, identifying a mechanism of reduced matrix destruction in these patients and further implicating MMPs in driving lung pathology in TB. No TB treatment currently targets this immunopathology, which ultimately causes morbidity and mortality (9). Doxycycline, a widely available MMP inhibitor, reduces expression of MMPs and also suppresses mycobacterial growth. Given its safety, cost, and availability in resource-poor settings, doxycycline may represent a new adjunctive therapy to reduce mortality in TB.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rene Goliath for facilitating the recruitment of patients and Ronnett Seldon for excellent technical support. They also thank the Biological Investigations Group at HPA, Porton Down, for support.

Footnotes

Supported by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research (N.F.W. and P.T.E.). P.T.E. and J.S.F. are grateful for support from the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) at Imperial College. N.F.W. was funded by the BRC and the Imperial College Wellcome Trust Centre for Clinical Tropical Medicine. G.M. was supported by the Wellcome Trust grant WT 081667 and received SATBAT research training that was Fogarty International Center and National Institutes of Health funded (grants NIH/FIC 1 U2RTW007373 and 5 U2RTW007370). R.J.W. receives support from the Wellcome Trust grants 084323 and 088316 and Medical Research Council, United Kingdom. Additional support was provided by the Imperial-London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine-University of Sussex-Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine-University of Cape Town (ILULU) consortium, funded from the European Union grant Sante/2006/105-061.

Author Contributions: N.F.W., G.M., R.J.W., J.S.F., and P.T.E. conceived and designed the clinical study, and S.O.C., J.M.D., A.W., J.S.F., and P.T.E. conceived and designed the animal modeling. N.F.W., T.O., G.M., and R.J.W. recruited the clinical cohort. S.O.C., D.L.K., J.A.T., and A.W. performed the guinea pig studies. N.F.W., N.A., L.T., S.S., L.S., and B.P. were involved in the cellular studies. F.A.M. performed the histological analysis. P.T.E. holds all primary data and is responsible for the integrity of the data. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the final submitted version.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Health.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201110-1769OC on February 16, 2012

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Dye C, Williams BG. The population dynamics and control of tuberculosis. Science 2010;328:856–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan ED, Iseman MD. Current medical treatment for tuberculosis. BMJ 2002;325:1282–1286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright A, Zignol M, Van Deun A, Falzon D, Gerdes SR, Feldman K, Hoffner S, Drobniewski F, Barrera L, van Soolingen D, et al. Epidemiology of anti-tuberculosis drug resistance 2002–07: an updated analysis of the global project on anti-tuberculosis drug resistance surveillance. Lancet 2009;373:1861–1873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shin SS, Keshavjee S, Gelmanova IY, Atwood S, Franke MF, Mishustin SP, Strelis AK, Andreev YG, Pasechnikov AD, Barnashov A, et al. Development of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis during multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;182:426–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gandhi NR, Shah NS, Andrews JR, Vella V, Moll AP, Scott M, Weissman D, Marra C, Lalloo UG, Friedland GH. HIV coinfection in multidrug- and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis results in high early mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;181:80–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yew WW, Sotgiu G, Migliori GB. Update in tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacterial disease 2010. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;184:180–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper AM. Cell-mediated immune responses in tuberculosis. Annu Rev Immunol 2009;27:393–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anandaiah A, Dheda K, Keane J, Koziel H, Moore DA, Patel NR. Novel developments in the epidemic of human immunodeficiency virus and tuberculosis coinfection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:987–997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frieden TR, Sterling TR, Munsiff SS, Watt CJ, Dye C. Tuberculosis. Lancet 2003;362:887–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwander S, Dheda K. Human lung immunity against mycobacterium tuberculosis: insights into pathogenesis and protection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:696–707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwan CK, Ernst JD. HIV and tuberculosis: a deadly human syndemic. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011;24:351–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elkington PT, D'Armiento JM, Friedland JS. Tuberculosis immunopathology: the neglected role of extracellular matrix destruction. Sci Transl Med 2011;3:71ps76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elkington PT, Nuttall RK, Boyle JJ, O'Kane CM, Horncastle DE, Edwards DR, Friedland JS. Mycobacterium tuberculosis, but not vaccine BCG, specifically upregulates matrix metalloproteinase-1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172:1596–1604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elkington P, Shiomi T, Breen R, Nuttall RK, Ugarte-Gil CA, Walker NF, Saraiva L, Pedersen B, Mauri F, Lipman M, et al. MMP-1 drives immunopathology in human tuberculosis and transgenic mice. J Clin Invest 2011;121:1827–1833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rand L, Green JA, Saraiva L, Friedland JS, Elkington PT. Matrix metalloproteinase-1 is regulated in tuberculosis by a p38 MAPK-dependent, p-aminosalicylic acid-sensitive signaling cascade. J Immunol 2009;182:5865–5872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Volkman HE, Pozos TC, Zheng J, Davis JM, Rawls JF, Ramakrishnan L. Tuberculous granuloma induction via interaction of a bacterial secreted protein with host epithelium. Science 2010;327:466–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salgame P. MMPs in tuberculosis: granuloma creators and tissue destroyers. J Clin Invest 2011;121:1686–1688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brinckerhoff CE, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinases: a tail of a frog that became a prince. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2002;3:207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golub LM, McNamara TF, Ryan ME, Kohut B, Blieden T, Payonk G, Sipos T, Baron HJ. Adjunctive treatment with sub-antimicrobial doses of doxycycline: effects on gingival fluid collagenase activity and attachment loss in adult periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol 2001;28:146–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elkington PT, Green JA, Friedland JS. Filter sterilization of highly infectious samples to prevent false negative analysis of matrix metalloproteinase activity. J Immunol Methods 2006;309:115–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawson L, Yassin MA, Thacher TD, Olatunji OO, Lawson JO, Akingbogun TI, Bello CS, Cuevas LE, Davies PD. Clinical presentation of adults with pulmonary tuberculosis with and without HIV infection in Nigeria. Scand J Infect Dis 2008;40:30–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elkington PT, Emerson JE, Lopez-Pascua LD, O'Kane CM, Horncastle DE, Boyle JJ, Friedland JS. Mycobacterium tuberculosis up-regulates matrix metalloproteinase-1 secretion from human airway epithelial cells via a p38 MAPK switch. J Immunol 2005;175:5333–5340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chambers MA, Williams A, Gavier-Widen D, Whelan A, Hughes C, Hall G, Lever MS, Marsh PD, Hewinson RG. A guinea pig model of low-dose Mycobacterium bovis aerogenic infection. Vet Microbiol 2001;80:213–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mavhu W, Dauya E, Bandason T, Munyati S, Cowan FM, Hart G, Corbett EL, Chikovore J. Chronic cough and its association with TB-HIV co-infection: factors affecting help-seeking behaviour in Harare, Zimbabwe. Trop Med Int Health 2010;15:574–579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sang QX, Jin Y, Newcomer RG, Monroe SC, Fang X, Hurst DR, Lee S, Cao Q, Schwartz MA. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors as prospective agents for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular and neoplastic diseases. Curr Top Med Chem 2006;6:289–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elkington PT, Green JA, Emerson JE, Lopez-Pascua LD, Boyle JJ, O'Kane CM, Friedland JS. Synergistic up-regulation of epithelial cell matrix metalloproteinase-9 secretion in tuberculosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2007;37:431–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andreu N, Fletcher T, Krishnan N, Wiles S, Robertson BD. Rapid measurement of antituberculosis drug activity in vitro and in macrophages using bioluminescence. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012;67:404–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parks WC, Wilson CL, Lopez-Boado YS. Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2004;4:617–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ganachari M, Ruiz-Morales JA, Gomez de la Torre Pretell JC, Dinh J, Granados J, Flores-Villanueva PO. Joint effect of MCP-1 genotype GG and MMP-1 genotype 2G/2G increases the likelihood of developing pulmonary tuberculosis in BCG-vaccinated individuals. PLoS ONE 2010;5:e8881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gapski R, Hasturk H, Van Dyke TE, Oringer RJ, Wang S, Braun TM, Giannobile WV. Systemic MMP inhibition for periodontal wound repair: results of a multi-centre randomized-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 2009;36:149–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alvarez JI, Krishnamurthy J, Teale JM. Doxycycline treatment decreases morbidity and mortality of murine neurocysticercosis: evidence for reduction of apoptosis and matrix metalloproteinase activity. Am J Pathol 2009;175:685–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meli DN, Coimbra RS, Erhart DG, Loquet G, Bellac CL, Tauber MG, Neumann U, Leib SL. Doxycycline reduces mortality and injury to the brain and cochlea in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. Infect Immun 2006;74:3890–3896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krakauer T, Buckley M. Doxycycline is anti-inflammatory and inhibits staphylococcal exotoxin-induced cytokines and chemokines. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2003;47:3630–3633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindeman JH, Abdul-Hussien H, van Bockel JH, Wolterbeek R, Kleemann R. Clinical trial of doxycycline for matrix metalloproteinase-9 inhibition in patients with an abdominal aneurysm: doxycycline selectively depletes aortic wall neutrophils and cytotoxic T cells. Circulation 2009;119:2209–2216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Green JA, Elkington PT, Pennington CJ, Roncaroli F, Dholakia S, Moores RC, Bullen A, Porter JC, Agranoff D, Edwards DR, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis upregulates microglial matrix metalloproteinase-1 and -3 expression and secretion via NF-kB and activator protein-1-dependent monocyte networks. J Immunol 2010;184:6492–6503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dheda K, Booth H, Huggett JF, Johnson MA, Zumla A, Rook GA. Lung remodeling in pulmonary tuberculosis. J Infect Dis 2005;192:1201–1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Izzo AA, Izzo LS, Kasimos J, Majka S. A matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor promotes granuloma formation during the early phase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis pulmonary infection. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2004;84:387–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hernandez-Pando R, Orozco H, Arriaga K, Pavon L, Rook G. Treatment with BB-94, a broad spectrum inhibitor of zinc-dependent metalloproteinases, causes deviation of the cytokine profile towards type-2 in experimental pulmonary tuberculosis in Balb/c mice. Int J Exp Pathol 2000;81:199–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.North RJ, Jung YJ. Immunity to tuberculosis. Annu Rev Immunol 2004;22:599–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balbin M, Fueyo A, Knauper V, Lopez JM, Alvarez J, Sanchez LM, Quesada V, Bordallo J, Murphy G, Lopez-Otin C. Identification and enzymatic characterization of two diverging murine counterparts of human interstitial collagenase (MMP-1) expressed at sites of embryo implantation. J Biol Chem 2001;276:10253–10262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Helke KL, Mankowski JL, Manabe YC. Animal models of cavitation in pulmonary tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2006;86:337–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim MJ, Wainwright HC, Locketz M, Bekker LG, Walther GB, Dittrich C, Visser A, Wang W, Hsu FF, Wiehart U, et al. Caseation of human tuberculosis granulomas correlates with elevated host lipid metabolism. EMBO Mol Med 2010;2:258–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mehra S, Pahar B, Dutta NK, Conerly CN, Philippi-Falkenstein K, Alvarez X, Kaushal D. Transcriptional reprogramming in nonhuman primate (rhesus macaque) tuberculosis granulomas. PLoS ONE 2010;5:e12266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nedeltchev GG, Raghunand TR, Jassal MS, Lun S, Cheng QJ, Bishai WR. Extrapulmonary dissemination of Mycobacterium bovis but not Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a bronchoscopic rabbit model of cavitary tuberculosis. Infect Immun 2009;77:598–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heifets LB. Antimycobacterial drugs. Semin Respir Infect 1994;9:84–103 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Collins L, Franzblau SG. Microplate alamar blue assay versus BACTEC 460 system for high-throughput screening of compounds against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1997;41:1004–1009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lougheed KE, Taylor DL, Osborne SA, Bryans JS, Buxton RS. New anti-tuberculosis agents amongst known drugs. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2009;89:364–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Balabanova Y, Ruddy M, Hubb J, Yates M, Malomanova N, Fedorin I, Drobniewski F. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Russia: clinical characteristics, analysis of second-line drug resistance and development of standardized therapy. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2005;24:136–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.MacArthur CG, Johnson AJ, Chadwick MV, Wingfield HJ. The absorption and sputum penetration of doxycycline. J Antimicrob Chemother 1978;4:509–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.