Abstract

Infections with Pseudomonas aeruginosa are a major health problem for immune-compromised patients and individuals with cystic fibrosis. A vaccine against P. aeruginosa has long been sought after, but is so far not available. Several vaccine candidates have been assessed in experimental animals and humans, which include sub-cellular fractions, capsule components, purified and recombinant proteins. Unique characteristics of the host and the pathogen have complicated the vaccine development. This review summarizes the current state of vaccine development for this ubiquitous pathogen, in particular to provide mucosal immunity against infections of the respiratory tract in susceptible individuals with cystic fibrosis.

Key words: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, vaccines, Pseudomonas antigens, cystic fibrosis, adenovirus

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an opportunistic Gram-negative bacterial pathogen found in most environments including water reservoirs and soil, is one of the leading nosocomial pathogen worldwide. P. aeruginosa is responsible for localized infections of a variety of organ systems including the respiratory tract, urinary tract, gastrointestinal tract, skin, eye, ear and joints and also systemic infections in susceptible individuals. Because P. aeruginosa is tolerant to a variety of physical conditions and is highly adaptable to survive in common environments, the hospital environments and equipments such as mechanical ventilators, intravenous lines, urinary or dialysis catheters, pacemakers, endoscopes, sinks and likewise can be potential reservoirs for P. aeruginosa infections. Given its ubiquitous presence, it is understandable that the healthy immune system is quite capable to control infections with P. aeruginosa. However, susceptible individuals, particularly those with an impaired immune system caused by HIV infection, organ transplantation, cytotoxic drugs or burns with vascular damage hindering localized phagocytosis, frequently suffer from infections with this pathogen. Chronic infections of the respiratory tract are a major cause for the increased morbidity and mortality for individuals with cystic fibrosis (CF).

Despite considerable advances in antimicrobial therapy, effective treatment and control of P. aeruginosa infections remains a persistent problem, primarily because of the natural resistance of the organism and its remarkable ability to acquire resistance to multiple antimicrobial agents by various mechanisms.1 As an alternative strategy to prevent P. aeruginosa infections in susceptible populations effective immunotherapies or vaccines against P. aeruginosa have long been sought after. Numerous P. aeruginosa antigens and delivery systems have been investigated as vaccine candidates; some have been tested in phase I-III clinical trials.2–4 However, despite the widespread presence and growing significance of P. aeruginosa infections and increasing rates of antibiotic treatment failure, no efficient and marketable vaccine against P. aeruginosa infections is currently available.

The increased understanding of P. aeruginosa pathogenesis and of pathogen-associated virulence factors helped in the identification of potential immunogens that could be used for a Pseudomonas vaccine. These immunogens are localized in structural components such as flagella, pili, outer membrane proteins or lipopolysaccharides or are part of secreted products such as mucoid exopolysaccharides, exotoxin A and proteases (Table 1).2–5 This review summarizes antigens and delivery systems in the development of a potential vaccine against P. aeruginosa.

Table 1.

Potential antigens for P. aeruginosa vaccine

| Antigens | Advantages | Limitations | Stage of development | Reference |

| LPS and O-polysaccharides | Generation of high levels of opsonic antibodies | High heterogeneity, Low immunogenicity, Pyrogenic and toxic | I–III phase | 21, 31–34, 36, 40 |

| MEP | Low heterogeneity | For CF use only | I phase | 45, 51, 52 |

| Outer Membrane proteins | Highly conserved and immunogenic Anti-OprF inhibits quorum-sensing through IFNγ binding to P. aeruginosa | No significant drawback | I/II phase | 137, 139, 142, 143, 146 |

| Flagella | Moderate heterogeneity, Adjuvant effect through TLR5 | Loss of flagella in CF variants | I–III phase | 80–82 |

| Pilin | High immunogenicity | High heterogeneity, Hidden receptor binding site | Preclinical | 94, 95, 98, 103 |

| PcrV, Exotoxin A and proteases | Neutralizes cytotoxic effects and pathology | Less effective in bacterial clearance | Preclinical | 105, 106, 108, 110, 111 |

| Killed | Presentation of multiple antigens to immune system | Toxicity | I phase | 56, 57 |

| Live attenuated (P. aeruginosa ΔaroA) | Presentation of multiple antigens to immune system | Residual virulence | Preclinical | 58, 59, 61, 62 |

| Attenuated Salmonella enterica delivered O-antigen or OprF-OprI | Efficient activation of mucosal immunity | Residual virulence | I/II phase | 68–70 |

| Ad vector delivered OprF | High immunogenicity and adjuvant properties | Pre-existing anti-Ad immunity | Preclinical | 157–159 |

Host Immune Response to P. aeruginosa

In order to develop an effective vaccine against P. aeruginosa, detailed knowledge of the host immune responses and the bacterial defense mechanisms is important. Both innate and adaptive immune responses work in synergy to act agaist P. aeruginosa infection. As P. aeruginosa is an extracellular pathogen, humoral, mucosal or systemic opsonizing immunity is most effective to prevent bacterial colonization and infection. However, T-cell responses can also mediate protective immunity in individuals with P. aeruginosa infections.6–8 Immunity to P. aeruginosa has been best studied in CF patients. During chronic lung infections in affected CF individuals, high levels of antibodies against components of P. aeruginosa such as surface O-polysaccharides and mucoexopolysaccharides are present, but they have poor opsonic activity and cannot clear the infection.9,10 Furthermore, the mucoid phenotype resists to the opsonic killing by antibodies because of the biofilm formation.11 High antibody titers have been associated with more severe lung disease.12 Comparing the CF patients with and without chronic lung infection suggested that a Th2 type response correlated with infection, implying that a Th1 response may be more protective.11,13

Lipopolysaccharide and O-Polysaccharides

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), the major component of the outer membrane of P. aeruginosa, is composed of lipid A, relatively conserved inner and outer core oligosachharides and highly variable peripheral long chain polysaccharides (O-antigen).14 The differences in chemical structure of O-antigens and hence the variation in immunological reactivity of P. aeruginosa isolates forms the basis of its classification into more than 20 heterogenous serotypes.14–16 The presence or absence of outer O-polysaccharide chains determines the smooth or rough phenotypes. The smooth form of P. aeruginosa is associated with the higher virulence, particularly systemic and acute infection while rough forms are often isolated from the chronically infected lungs of CF patients.

LPS has remained the most widely characterized and investigated vaccine antigen since the 1960s because of its surface accessibility and perceived high immunogenicity. Early vaccination studies with bacterial extracts identified the LPS component of these vaccines as the major target for immune recognition.17–19 However, the lipid A-associated toxic effects hindered its widespread clinical development. The issue of LPS toxicity could be satisfactorily addressed by incorporation of complete core LPS into liposomes to reduce its toxicity. These vaccines still elicited protection against a wide variety of pathogens.20,21 Alternatively, the non-toxic high molecular weight O-polysaccharides, without the lipid component, have been used as an effective immunogen.22,23 O-polysaccharides were conjugated to carrier proteins such as exotoxin A or tetanus toxoid to improve their immunogenicity.23,24 To counter the O-antigen heterogeneity, multivalent vaccines have been developed to target a broader range of clinically active P. aeruginosa serotypes. Multivalent LPS-based vaccine have been clinically evaluated in patients with leukemia,25–27 burns28 or CF26,29 with variable efficacies. However, because of the toxic side effects of most of the vaccine preparations, they were not pursued for the routine application. An improved LPS-based polyvalent vaccine (16 strains) was investigated in CF patients prior to P. aeruginosa colonization.30 However, the vaccine failed to reduce the rate of Pseudomonas colonization when compared with the non-vaccinated control group.31 The same vaccine was also tested in burn patients with inconclusive results.32–34

An octavalent O-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine (Aerugen®) was developed by conjugating purified P. aeruginosa O-polysaccharide molecules from eight strains and conjugated with exotoxin A.35–39 The efficacy of this vaccine was compared in CF patients not yet colonized with P. aeruginosa, to a retrospectively identified control group in a non-blind trial. Initial results were quite encouraging as high levels of O-polysaccharide-specific opsonizing antibodies with anamnestic properties were induced. After 6 y, 35% of the immunized subjects were infected with P. aeruginosa compared with 75% of the control subjects.36 Moreover, the persistence of high-affinity antibodies among immunized subjects strongly correlated with lower rate of infection over this observation period. Even 10 y following immunization, a significant reduction in the frequency of chronic infection with P. aeruginosa as well as improved overall health status was seen.40 No apparent adverse effects, commonly associated with the previous studies, were observed. However, a subsequent double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase III study involving 476 patients with CF failed to confirm the initial positive results and the further development of this vaccine was suspended (cws.huginonline.com/C/132631/PR/200607/1064252_5_5.html).

Despite these extensive efforts for more than 40 y, realization of clinically applicable LPS or O-polysaccharide-based vaccines remains elusive. Extensive serological heterogeneity, LPS-associated toxicity, cost and complexity of development of lipid free multivalent-conjugates are the major obstacles in vaccine development. Colonization of CF patients with mostly rough isolates that most likely escape O-antigen specific opsonizing antibodies is one reason for the lack of efficacy of an LPS-based vaccine in this disease. Even if the CF patients are immunized prior to Pseudomonas colonization, the bacteria may switch rapidly to the rough phenotype under the O-antigen-specific immunological pressure. Another concern for the usefulness of LPS-based vaccine is the observed inconsistency in immune responses in different species41 that makes it difficult to predict the vaccine performance in humans. Furthermore, vaccination with a multivalent LPS O-antigen vaccine composed of antigens from serologically distinct strains within the same overall serogroup showed interference in the immunogenicity of the individual components.42

Mucoid Exopolysaccharide

Chronic infection with P. aeruginosa in the respiratory tract of CF patients is characterized by the conversion of the non-mucoid to the mucoid phenotype due to overproduction of mucoid exopolysaccharide (MEP; also known as alginate). MEP, a linear polymer of partially acetylated D-mannuronic acid and L-guluronic acid,43 is the major component of the P. aeruginosa biofilm matrix and thus critical in persistence of the bacteria in the CF lung.44 In contrast to LPS, MEP is relatively conserved between strains, which makes it an attractive vaccine antigen.45–47 CF patients can naturally generate MEP-specific antibodies.46 These are, however, primarily non-opsonizing and therefore not effective to clear the infection. The detection of higher levels of serum anti-MEP opsonophagocytic antibody titers in older CF patients that remained free of P. aeruginosa infection rationalized the development of MEP-based vaccines more than 20 y ago.48 Human and animal studies confirmed the role for MEP-specific opsonizing antibodies in facilitating bacterial clearance.45,49 An initial human trial elicited long-lived opsonic antibodies in 80–90% of the volunteers only when a high molecular-weight MEP was used for vaccination.45 To improve immunogenicity, MEPs have been conjugated to various carrier proteins such as exotoxin A, tetanus toxoid or keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH).50–52 In mice and rabbits, these vaccine preparations successfully enhanced the MEP-specific immune responses and elicited opsonizing antibodies against heterologous MEPs. The preservation of O-acetyl groups and preventing depolymerization of MEP during the conjugate vaccine preparation resulted in broader cross-reactivity among heterologous strains.52 However, despite the encouraging results in preclinical studies, a successful clinical product has not been yet developed. MEP-based vaccines may still hold potential, though, for the chronically infected CF population.

Whole-Cell Killed and Live-Attenuated Vaccines

Whole-cell killed or live-attenuated vaccines present multiple bacterial antigenic components and can thus potentially induce diverse immunologic effectors against P. aeruginosa. Intestinal mucosal immunization with a whole-cell killed P. aeruginosa vaccine in a rodent model of acute P. aeruginosa lung infection resulted in enhanced clearance of the bacteria from the lung as well as improved survival.53,54 The protective immune mechanisms following mucosal immunization with this vaccine were thought to be dependant on antigen-specific CD4+ T cells, the recruitment and activation of alveolar macrophages and neutrophils, TNFα, IL-1 and IFNγ and P. aeruginosa-specific lung mucosal and serum IgG and IgA.6,53–55 Oral immunization of bronchiectasis patients with an enteric-coated whole-cell killed P. aeruginosa vaccine resulted in significant reduction of P. aeruginosa in the sputum, which was related to P. aeruginosa-specific lymphocyte responses.56 Oral immunization of healthy volunteers with killed pseudomonas vaccine was safe and increased pseudomonas-specific serum antibodies, most notably IgA, and promoted opsonophagocytotic killing of P. aeruginosa.57 Liveattenuated P. aeruginosa strains have been created by introducing deletion mutations into aroA gene.58–60 These mutants are unable to synthesize aromatic amino acids and cannot efficiently acquire them from the host and hence can survive at detectable levels only up to 3–4 d following administration.59 Intranasal immunization of mice and rabbits with P. aeruginosa aroA mutants elicited high titers of opsonic antibodies59 and conferred protection against acute fatal pneumonia caused by serogroup-homologous strains61 with some protection against serologous-heterologous strains.60 Interestingly, in a murine corneal infection model, active immunization with an aroA deletion mutant of the P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 (PAO1ΔaroA) or passive immunotherapy with rabbit antiserum raised against PAO1ΔaroA protected against corneal infections caused by heterologous serogroups of P. aeruginosa.62 Importantly, in addition to prophylactic efficacy, the PAO1ΔaroA antiserum was therapeutically effective even when started as late as 24 h after infection. Outer membrane antigens, but not the LPS O-antigen, were the protective component of the vaccine in this setting.62 In a recent study, mucosal vaccination with a multivalent vaccine composed of live-attenuated P. aeruginosa strains (ΔaroA) induced multifactorial immune responses against diverse bacterial antigens and protected against acute fatal lung infection.58 Opsonophagocytic antibodies against the LPS O-antigen and, interestingly, also against the LPS core and bacterial surface proteins were generated. Furthermore, the use of multivalent live-attenuated vaccine did not generate immunological interference in opsonic-antibody responses which had been observed with multivalent purified O-antigen vaccines.58

Whole-cell killed and live-attenuated vaccines provide an easy, safe and efficacious method to induce anti-P. aeruginosa immunity against broad range of antigens. Development of additional means to attenuate virulence while maintaining immunogenicity will further facilitate clinical realization of such vaccines.

Live-Attenuated Salmonella Strains for P. aeruginosa Antigen Delivery

Attenuated Salmonella species expressing heterologous antigens are promising vaccine vehicles, especially for mucosal immunization63 and have been successfully developed to induce specific immune responses against variety of mucosal infections.64–67 Oral immunization of mice with attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium SL3261 expressing P. aeruginosa O11 O-antigen resulted in enhanced pulmonary bacterial clearance and increased survival time after intranasal challenge with homologous, but not with heterologous P. aeruginosa strain.68 Intranasal immunization in mice with the same vaccine elicited more robust and long-term mucosal and systemic immune responses that provided complete protection against P. aeruginosa challenge in pneumonia, burns and eye injury, indicating protection at distant sites.69 Another Salmonella strain SL3261-based live-attenuated vaccine that expressed pseudomonas outer membrane fusion protein OprF-OprI, induced anti-OprF-OprI-specific IgG and IgA antibodies in the respiratory mucosa after an oral primary and systemic booster vaccination schedule. In a phase I/II clinical trial enrolling healthy volunteers, live-attenuated Salmonella vaccines expressing OprF-OprI were compared in their capacity to induce lung mucosal immunity after systemic, oral or nasal inoculation.70 While systemic and mucosal immunization induced comparable OprF-OprI-specific serum antibody titers, IgG and IgA in the lower airways were only induced following mucosal (nasal or oral) immunization.70

Overall, the use of Salmonella vaccines may be an efficient means to generate mucosal immunity.

Flagella

P. aeruginosa flagella is essential for motility, chemotaxis, invasiveness and adhesion.71–73 Flagella also activates host inflammatory responses due to its intrinsic adjuvant activity mediated through TLR5.74 Therefore, it can also be used as a carrier protein to conjugate low immunogenic carbohydrate antigens such as LPS, O-polysaccharides or MEPs. Flagellin, the primary protein component of flagella, is divided into the heterogenous typea and the serologically uniform type-b flagellin.75 Consequently, a successful vaccine has to be bivalent to be broadly protective.

Immunizations with flagella reduced the mobility and spread of P. aeruginosa and provided protection against lethal infection in a burned mouse model.76,77 Administration of human anti-flagella monoclonal antibodies provided protection against P. aeruginosa infections in mice.78,79 Intramuscular administration of a monovalent P. aeruginosa flagella vaccine was well tolerated in healthy volunteers and elicited high and long-lasting systemic and lung antibody titers.80 In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, multicenter phase III trial on 483 CF patients without P. aeruginosa colonization 4 intramuscular injections of a bivalent P. aeruginosa flagella vaccine were given over a 14-mo period and evaluated over a 2 y period.81 The vaccine was safe and immunogenic and lowered the risk of infection with P. aeruginosa. In the group of 381 CF patients that received all 4 vaccinations or placebo treatments, a significant reduction in colonization with P. aeruginosa was observed in vaccinated patients (19.6% colonized) compared with the placebo group (30.7% colonized). Significantly fewer P. aeruginosa isolates, harboring the flagella subtype that was included in the vaccine, were detected in the lung of vaccinated patients compared with the placebo group.81 It was therefore suggested that the inclusion of additional P. aeruginosa flagella types in future vaccine preparations may improve the efficacy of a flagella vaccine in CF patients.

A DNA vaccine encoding recombinant type-a or type-b P. aeruginosa flagellin was immunogenic.82 Interestingly, anti-flagellin antibodies, though cross-reactive, were more effective against a heterologous flagella challenge because the anti-flagella antibodies interfered with the interaction of homologous flagellin with TLR5. A flagellin mutant DNA vaccine encoding the mutagenized form of flagellin with impaired ability to interact with TLR5 provided cross-reactive protection against both flagellin types.82 Vaccine efficacy of a flagella vaccine was superior to that of a flagellin vaccine.83 Moreover, antibodies to flagellin monomers inhibited TLR5 activation and associated activation of innate immunity.83

Mono- or bivalent flagella vaccines have shown promise in human trials by inducing long-lasting protective systemic or localized antibodies, but the response has overall only been modest. Introduction of additional flagella types may improve the overall efficacy. Another caveat is that inhibition of flagellum biosynthesis resulting in decreased expression of flagella have been observed in mucoid P. aeruginosa isolates from CF patients,84 which questions the utility of such vaccines in patients who are already colonized with P. aeruginosa.

Pili

As other Gram-negative bacteria, P. aeruginosa expresses pili on their surface, which are polymeric assemblies of the pilin protein that assists in bacterial adhesion, biofilm formation and twitching motility. Pilus antigens are serologically heterogenous,85 and can be classified into five distinct phylogenetic groups.86 Examination of pilin alleles among CF and non-CF human isolates showed marked distinction in allele distribution and association with accessory genes.86 Although the N-terminal region of mature pilin is highly conserved, it is not an ideal vaccine candidate because of its hydrophobic nature and limited accessibility. C-terminus containing a disulfide-bonded loop structure responsible for interaction with the host cellular receptor asialoGM1, is relatively less conserved.85,87,88 However, irrespective of the amino acid sequence, the putative C-terminal receptor binding site was found to be structurally conserved89–91 and was therefore expected to inhibit P. aeruginosa attachment and provide cross-protection when used as a vaccine antigen. But, preclinical studies using the receptor binding region of pilin showed inconsistent results in achieving cross-reactivity and protection.92,93 It later turned out that the receptor binding domain of P. aeruginosa pili is not surface exposed and thus limits its use as a vaccine antigen.89–91

Using purified pili protein or pilin peptides conjugated to carrier proteins as vaccine candidates showed efficacy in mice.92,94 Also, a dual-function chimeric exotoxin A-pilin vaccine led to reduction in bacterial adherence and neutralized the cytotoxic activity of exotoxin A in rabbits.95 O-linked, pilin glycosylation is common among P. aeruginosa strains. The P. aeruginosa strain 1244 naturally presents an O-antigen repeating unit covalently linked to each pilin monomer and seemed therefore to be a good vaccine candidate.96,97 Immunization with 1244 pilin provided protection in a murine model for respiratory infections and a burn model.98 This study also presented a pilin glycosylation system that could be useful for the development of anti-O-antigen glycoconjugate vaccines.98 Consensus synthetic peptide sequences analogous to the receptor binding region of P. aeruginosa pilin have been proposed as immunogens, which could elicit cross-reactive antibodies that would inhibit adherence of a broad range of P. aeruginosa strains.99–103 These anti-pilus synthetic peptide conjugates also generated higher antibody titers with higher affinity compared with a pilin protein vaccine.104

Pilin-based vaccines have shown variable efficacies to reduce bacterial adherence. The serological heterogeneity and hidden conserved binding site complicates the further development of pilin-based vaccines. So far there have been no human studies with pilin vaccines.

Type III Secretion System, Extracellular Toxins and Proteases

P. aeruginosa, like other gram-negative bacteria, employs the type III secretion system (T3SS) to deliver effector proteins responsible for virulence, tissue injury and cytotoxicity to the cytosol of host cells. PcrV protein, a component of T3SS is located on the bacterial surface and is required for translocation of these effector proteins. Immunization with a vaccine targeting PcrV-induced protective immunity in mice, decreased lung inflammation and injury in a murine lung infection model105 and a burn mouse model.106 Inhibition of the translocation of type III effectors by anti-PcrV was suggested as the mechanism for the protection.105 Protection against P. aeruginosa was non-O-serotype-specific, though a supplemental anti-toxin treatment was required with a high-level toxin A-producing strain to enhance survival.106 A multivalent T3SS-based protein vaccine, including P. aeruginosa PcrV and needle tip proteins from four other gram-negative bacteria also showed to be immunogenic.107

Several exotoxins and extracellular enzymes of P. aeruginosa are responsible for its virulence in various disease manifestations. Exotoxin A, an ADP-ribosyl transferase that inhibits host protein synthesis, is the most toxic virulence factor of P. aeruginosa. Immunization with a truncated exotoxin A subunit or DNA vaccine elicited specific antibodies and protected mice from the challenge with lethal doses of wild type exotoxin A.108–110 In a recent study, a toxoid exotoxin A vaccine also protected burned mice against an exotoxin A challenge.111

Elastase and alkaline proteases interfere with the host immune system by cleaving immunoglobulins,112,113 inhibiting cytokines,114,115 and interfering with the immune cell functions.116–118 Immunization with elastase and alkaline protease toxoids were effective in P. aeruginosa infection models of hemorrhagic pneumonia in minks,119 corneal ulcers120 and burns in mice.121 Immunization with an elastase peptide reduced the severity of lung infections in rats.122 In a mouse model of P. aeruginosa gut-derived sepsis, immunization with alkaline protease, elastase and exotoxin A provided protection when all three were used combined, but failed when each component was used alone.123

Overall, immunization against PcrV and extracellular toxins seems efficient to block the inflammatory and cytotoxic effects induced by P. aeruginosa and they may thus be useful as part of multicomponent vaccines.95,124 None of these vaccines has yet been tested in humans.

Outer Membrane Proteins

Pseudomonas outer membrane proteins (Opr) form porins and other structural and functional components on the bacterial cell surface. OprF and OprI are the major Opr's that are surface-exposed and antigenically conserved in wild-type strains of P. aeruginosa.125,126

Many of the initial vaccination studies demonstrated that immunization with either OprF or OprI as immunogens elicits cross-reactive, opsonizing and protective antibodies in animal models or humans.127–134 To enhance synergistic immunogenicity, a recombinant hybrid vaccine using immunogenic epitopes from OprF and OprI was developed. Active or passive immunization with this OprF-OprI vaccine was protective against systemic P. aeruginosa infection in various animal models.135,136 In phase I/II human trials, intramuscular administration of the OprF-OprI vaccine adsorbed on aluminum hydroxide was safe and induced specific antibodies in healthy volunteers and burn patients.137,138 To enhance the formation of mucosal antibodies in the respiratory tract, an OprF-OprI vaccine was formulated in emugel and sodiumiodecylsulfate and administered intranasally. Immunization of healthy individuals was safe and elicited a long lasting systemic and lung mucosal antibody response.139–141 Intranasal immunization followed by systemic boost induced higher levels of systemic anti-P. aeruginosa IgG compared with intranasal priming and intranasal boost.141 The levels of mucosal P. aeruginosa-specific IgA or IgG antibodies were similar with both immunization schedules141 and were detected up to 1 y following immunization.142 Even as the systemic boost induced higher serum IgG antibodies, nasal boost induced a longer-lasting mucosal IgA and IgG response against P. aeruginosa.142 A subsequent phase I/II clinical trial in patients with chronic pulmonary disease demonstrated that nasal OprF-OprI vaccination followed by systemic boost was well tolerated and induced airway mucosal P. aeruginosa-specific IgG and IgA up to 6 mo in more than 90% of the vaccinees.143

An Opr vaccine (CFC-101), composed of Opr extracts from four P. aeruginosa strains, induced Opr-specific antibody titer with opsonophagocytic activity and increased P. aeruginosa blood clearance rate in healthy volunteers and burn patients.144–146 A chimeric vaccine composed of Pseudomonas exotoxin A, OprF and OprI components induced high antibody titers against the exotoxin and OprF, demonstrating that this vaccine could both, neutralize exotoxin A cytotoxicity and increase opsonophagocytic uptake of divergent P. aeruginosa strains.147 Another fusion protein vaccine containing OprF Epitope 8-OprI-type a and b-flagellin, was highly effective in mice and non-human primates.148,149

OprF appears to be a key player in the adaptation of P. aeruginosa to the host immune defense. P. aeruginosa senses the activation of immune response by binding to IFNγ through OprF, which leads to the development of a more virulent phenotype.150 In a recent study it was demonstrated that OprF-OprI vaccinated sera from human volunteers inhibit P. aeruginosa binding to IFNγ, suggesting an additional effector mechanism of OprF containing vaccines.151 OprI was demonstrated to adhere to the mucosal surfaces of the respiratory and intestinal tract and may so act as a mucosal carrier to facilitate antigen delivery to antigen-presenting cells.152

In addition to conventionally extracted or recombinant protein preparations, Opr have been successfully tested in several other formulations including DNA vaccines,129,130 peptide vaccine,153 viral vectors,154–159 dendritic cell-pulsed,160 or heterologously expressed in bacterial vectors.70 Furthermore, many of the chimeric vaccines include OprF/OprI as their critical component.147–149,154–156,161

Opr continues to be one of the most promising vaccine antigens to provide protection against a broad range of P. aeruginosa strains. Controlled clinical trials are required for further validation of the efficacy of Opr vaccines.

Adenoviral Vectors as Platforms for a P. aeruginosa Vaccine

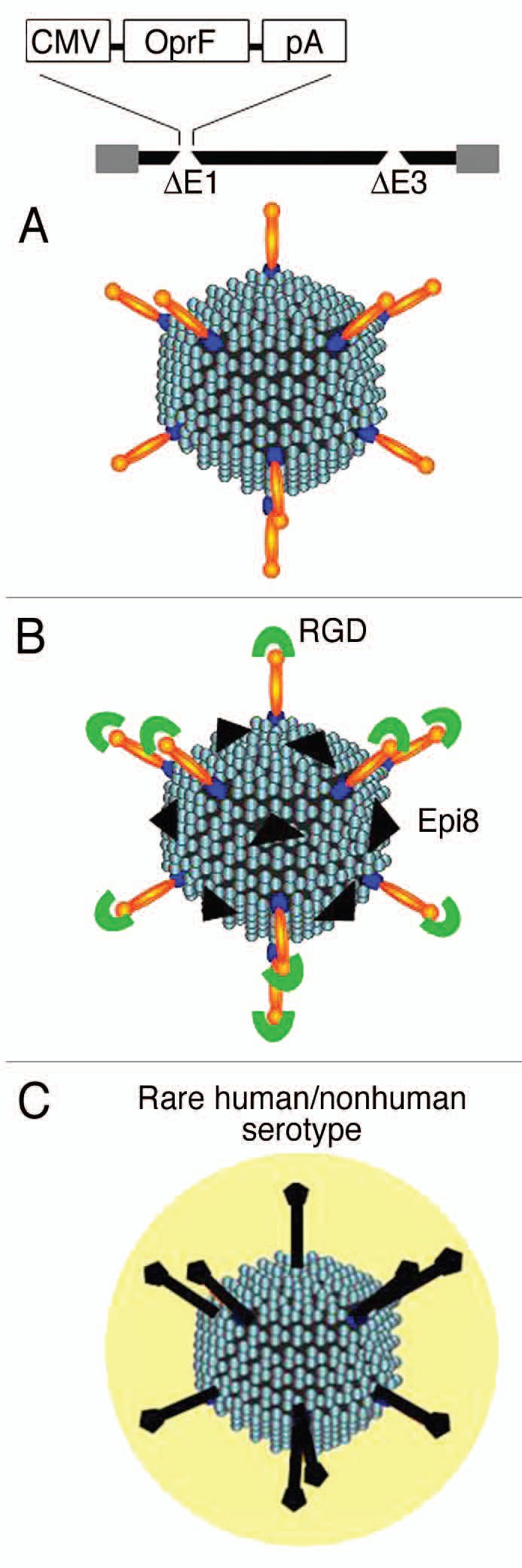

Adenovirus (Ad) vectors are attractive delivery vehicles for genetic vaccines because of their abilities to act as immune system adjuvants and to rapidly evoke robust immune responses against the transgene product and viral capsid proteins. Ad vectors are currently being evaluated in preclinical and clinical studies for a variety of pathogens including HIV, ebola, influenza, tuberculosis and malaria.162–170 Ad vector system might present a useful platform for anti-pseudomonas vaccines and indeed, immunization with a human Ad serotype 5 (Ad5) or a non-human primate Ad serotype C7 expressing OprF resulted in anti-OprF humoral and cellular immunity and provided protection to pulmonary infections with P. aeruginosa in mice.157,158 In addition Ad vectors can be engineered to modify Ad capsid proteins to increase immunogenicity or for targeting170 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Strategies for Ad vector-based vaccines against P. aeruginosa. (A) Expression of transgenes encoding P. aeruginosa antigenic proteins (e.g., OprF) by replication-defective (deletions in E1 and E3 genes) Ad vectors. (B) Modification of Ad capsid proteins to incorporate antigenic epitope (e.g., Epi8 of OprF in hexon) or targeting moities (e.g., RGD on fiber knob to target integrins on dendritic cells). (C) Use of alternate serotypes or non-human Ad vectors to circumvent the pre-existing immunity to prevalent human Ads.

The effectiveness of the Ad-based vaccine results, in part, from the ability of Ad vectors to transfer genes to antigen-presenting cell, particularly dendritic cells (DC) that allows antigen presentation through both class I and II pathways.171,172 Addition of the integrin-binding RGD motif to the Ad fiber knob targets Ad vector to integrin-rich DCs and thus improving vaccine efficacy.173–175 In a murine model, RGD-capsid-modified Ad vector expressing OprF induced increased anti-OprF cellular and protective immunity compared with non-capsid-modified vector expressing OprF (AdOprF).158

One of the limitation of Ad vector as vaccine carrier is that the anti-Ad immunity following the first immunization prevents the boosting of the immune response by repeat administration of the same Ad serotype. One of the strategies to circumvent this limitation is to incorporate the immunogenic vaccine epitopes into the Ad capsid proteins. A capsid modified Ad vector incorporating a immune-dominant B-cell epitope of P. aeruginosa OprF (Epi8) into loop 1 of hypervariable region 5 of hexon (AdZ.Epi8) was developed and evaluated for immunogenic and protective properties.159 Immunization of mice with AdZ.Epi8 induced Epi8-specific cellular and humoral immune responses and resulted in protection against a lethal pulmonary challenge with P. aeruginosa. Importantly, repeated administration of this vector resulted in boosting of the anti-OprF humoral and anti-Epi8 cellular responses.159

Subsequently, an improved dual capsid modified (Epi8 into hexon and RGD motif into fiber proteins) Ad vector expressing OprF (AdOprF.RGD.Epi8) was generated. In a murine model, AdOprF.RGD.Epi8 elicited increased OprF-specific cellular immune responses and protection compared with immunization with unmodified Ad vector expressing OprF and also enabled repeat administration to boost the anti-OprF humoral response.158 In a comparative study, influence of the location of an epitope incorporated into different capsid proteins on anti-epitope immunogenicities was investigated.176 Interestingly, despite presenting the epitope in least copy numbers, Ad vector with epitope incorporated into its fiber knob elicited the strongest anti-epitope humoral and CD4 cellular immunity compared with when the same epitope was incorporated in hexon, penton base or protein IX. This indicates the importance of choice of incorporation site in Ad capsid proteins for the generation of epitope-specific immune response.176 Analyses of intra-fiber locations for epitope incorporation demonstrated that insertion of P. aeruginosa Epi8 into FG or HI loops elicited the highest anti-OprF immunogenicity compared with CD, DE or IJ loops (unpublished observations).

Efficacy of Ad5-based vaccines is limited by widespread pre-existing anti-Ad5 immunity in human populations that inhibit the levels and duration of transgene expression.177 To circumvent this problem, application of alternative Ad vectors based on less prevalent human or non-human Ad serotypes, including nonhuman primate-derived Ad vectors has been proposed.162,168,178 A chimpanzee Ad vector expressing P. aeruginosa OprF (AdC7OprF) induced long-term anti-OprF systemic, mucosal and protective immunity following intramuscular or airway mucosal immunization.157 In comparison to Ad5OprF, AdC7OprF induced higher anti-OprF IgA levels in lung epithelial lining fluid, lung T-cell immunity after systemic administration and long-term mucosal anti-OprF IgG and IgA response after mucosal administration.157

Recently, Ad-based vaccines received a setback when a comprehensive phase II STEP trial with MERK Ad5-based HIV-1 vaccine was prematurely terminated because of a two-fold increase in the incidence of HIV acquisition among the vaccinated group with high anti-Ad5 neutralizing antibodies titers compared with placebo recipients.179,180 It was hypothesized that vaccination of Ad5 seropositive subjects caused activation and expansion of pre-existing Ad5-specific CD4+ T cells, potentially serving as targets for HIV infection.181 However, several studies have subsequently indicated no causative role of Ad5-specific CD4+ T cells in increasing HIV-1 susceptibility in the seropositive individuals.182–185 An alternative model has been proposed that following vaccination Ad5 immune complexes are formed that activate DC-T cell axis, which together with the possible persistence of the Ad5 vaccine, may set up a permissive environment for HIV-1 infection.186 Nevertheless, since P. aeruginosa does not target CD4+ T cells through infection, former findings are HIV-1-specific and Ad-based pseudomonas vaccines are expected to be successful.

Ad vectors can also be engineered to exogenously express TLR agonists to further enhance the immune responses to antigenic targets.187 Overall, an adenoviral vaccine represents a safe, flexible, effective and widely characterized vaccine delivery system. Encouraging results in preclinical vaccine studies favors further development of Ad-based pseudomonas vaccines.

Passive Immunotherapy

Given the importance of antibodies to provide protection against P. aeruginosa, passive transfer of protective antibodies is a viable approach to prevent or control the infection. Passive immunotherapy can potentially provide rapid protection in high-risk groups such as burn patients, patients in the ICU and patients with an impaired immune system who cannot mount an effective immunity in response to active immunization. Several preparations of P. aeruginosa-specific hyperimmune intravenous IgG (IVIG) from vaccinated donors have been used as experimental therapies. Immune globulin from patients immunized with a multivalent P. aeruginosa LPS-based vaccine showed protective efficacy when given to burn patients.34,188 This product was not further pursued. Another trial used tetravalent IVIG with some efficacy in burn patients.189 A P. aeruginosa-intravenous IVIG product prepared from plasma donors immunized with an octavalent P. aeruginosa LPS O-side chain conjugate vaccine (Aerugen®),190,191 did not provide protection in ICU patients and was associated with adverse reactions.192 Passive immunotherapy using murine or human monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) is considered superior to IVIG due to improved specificity, lower risk of biohazard contamination, mass production with consistent quality and the selection of highly protective epitopes from otherwise poorly immunogenic antigens. Many mouse and human mAbs with specificity for LPS O-antigens have shown protection against infection in animal models.193–197 Polyreactive mAbs targeting more conserved LPS core epitopes provided cross-protection against heterologous P. aeruginosa.198–200 A human mAb cocktail of three IgM mAbs, each directed against P. aeruginosa O-polysaccharide, LPS core polysaccharide or flagellin type b, showed promising results in patients with pneumonia and/or burn wounds as far as safety, antigenicity and efficacy was concerened.201 Using a more novel approach, transgenic mice with its immunoglobulin genes replaced with human immunoglobulin loci were used to generate a panel of O-polysaccharide-specific human IgG2 mAbs targeted against multiple P. aeruginosa serotypes.202 The majority of these antibodies were opsonophagocytic and protective against fatal sepsis in neutropenic mice upon challenge with multiple, however homologous, P. aeruginosa strains.202 Recently, the full length cDNA of human mAb directed against the LPS O-antigen of serotype O11 of P. aeruginosa (KBPA-101) has been isolated from plasma cells of a volunteer immunized with O-antigen-toxin A conjugate vaccine.203 KBPA-101 is an IgM/k isotye antibody that demonstrated high opsonophagocytic activity and provided protection against P. aeruginosa challenge in burn wound sepsis and acute lung infection models.203,204 In a phase I clinical study, intravenous administration of KBPA-101 mAb was well tolerated205 in human volunteers and a phase II trial in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia is ongoing. Pharmacokinetics of other preparations of human mAbs206,207 have also been studied in human patients, however, none of them were further developed for clinical use.

Human mAbs specific to conserved MEP epitopes mediated killing and protected against infection not only of highly mucoid CF isolates of P. aeruginosa, but interestingly also of low alginate-producing nonmucoid strains in a murine model of acute pneumonia.208 Similarly, several antibodies targeting other virulence-associated antigens of P. aeruginosa such as flagella,75,78,79,209–212 pilus,92 PcrV213–218 and exotoxin A219–221 have been developed and successfully tested in various animal models. Therapeutic potential of these reagents remain to be tested in clinical settings. Another novel approach to deliver a monoclonal antibody against P. aeruginosa would be through genetic delivery using gene transfer vectors. Antibody molecules have been expressed using a variety of viral vector systems. Although this has not been developed for P. aeruginosa monoclonal antibodies yet, monoclonal antibodies against other pathogens have been tested in animal models222–226 and this could provide longer expression of the antibody, which could be regulated by the vector system used.

Summary

Despite intense efforts over the past few decades a marketable vaccine against P. aeruginosa has not yet evolved. For active immunization the Opr's, either delivered as protein or genetic vaccines, are promising vaccine candidates. The development of monoclonal antibodies against several non-Opr also show promise to control infections in susceptible individuals. A vaccine to delay or prevent initial pulmonary infection in individuals with CF would have significant impact and may be accomplished in the future.

Acknowledgments

Studies in the laboratory were supported by grants from NIAID U01 AI069032 and R01 AI72238. A.S. is supported by the Lili Foo Hing Fund.

Abbreviations

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MEP

mucoid exopolysaccharide

- KLH

keyhole limpet hemocyanin

- Opr

outer membrane protein

- T3SS

type III secretion system

- Ad

adenovirus

- DC

dendritic cell

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- IVIG

intravenous immunoglobulins

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

References

- 1.Tenover FC. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria. Am J Infect Control. 2006;34:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2006.05.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doring G, Pier GB. Vaccines and immunotherapy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Vaccine. 2008;26:1011–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holder IA. Pseudomonas immunotherapy: a historical overview. Vaccine. 2004;22:831–839. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sedlak-Weinstein E, Cripps AW, Kyd JM, Foxwell AR. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: the potential to immunise against infection. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2005;5:967–982. doi: 10.1517/14712598.5.7.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanislavsky ES, Lam JS. Pseudomonas aeruginosa antigens as potential vaccines. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1997;21:243–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1997.tb00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunkley ML, Clancy RL, Cripps AW. A role for CD4+ T cells from orally immunized rats in enhanced clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from the lung. Immunology. 1994;83:362–369. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunkley ML, Cripps AW, Reinbott PW, Clancy RL. Immunity to respiratory Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection: the role of gut-derived T helper cells and immune serum. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;371:771–775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevenson MM, Kondratieva TK, Apt AS, Tam MF, Skamene E. In vitro and in vivo T cell responses in mice during bronchopulmonary infection with mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;99:98–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb03478.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruderer U, Cryz SJ, Jr, Schaad UB, Deusinger M, Que JU, Lang AB. Affinity constants of naturally acquired and vaccine-induced anti-Pseudomonas aeruginosa antibodies in healthy adults and cystic fibrosis patients. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:344–349. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.2.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ciofu O, Petersen TD, Jensen P, Hoiby N. Avidity of anti-P. aeruginosa antibodies during chronic infection in patients with cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 1999;54:141–144. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.2.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen PO, Givskov M, Bjarnsholt T, Moser C. The immune system vs. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2010;59:292–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoiby N. Antibiotic therapy for chronic infection of pseudomonas in the lung. Annu Rev Med. 1993;44:1–10. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.44.020193.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moser C, Kjaergaard S, Pressler T, Kharazmi A, Koch C, Hoiby N. The immune response to chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection in cystic fibrosis patients is predominantly of the Th2 type. APMIS. 2000;108:329–335. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2000.d01-64.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knirel YA. Polysaccharide antigens of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1990;17:273–304. doi: 10.3109/10408419009105729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bystrova OV, Knirel YA, Lindner B, Kocharova NA, Kondakova AN, Zahringer U, et al. Structures of the core oligosaccharide and O-units in the R- and SR-type lipopolysaccharides of reference strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa O-serogroups. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2006;46:85–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2005.00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Homma JY, Ghoda A, Goto S, Jo K, Kato I, Kodama H, et al. Proposal of an international standard for the infra-specific serologic classification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Jpn J Exp Med. 1979;49:89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexander JW, Fisher MW, MacMillan BG, Altemeier WA. Prevention of invasive pseudomonas infection in burns with a new vaccine. Arch Surg. 1969;99:249–256. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1969.01340140121018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crowder JG, Fisher MW, White A. Type-specific immunity in pseudomonas diseases. J Lab Clin Med. 1972;79:47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fisher MW, Devlin HB, Gnabasik FJ. New immunotype schema for Pseudomonas aeruginosa based on protective antigens. J Bacteriol. 1969;98:835–836. doi: 10.1128/jb.98.2.835-836.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett-Guerrero E, McIntosh TJ, Barclay GR, Snyder DS, Gibbs RJ, Mythen MG, et al. Preparation and preclinical evaluation of a novel liposomal complete-core lipopolysaccharide vaccine. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6202–6208. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.11.6202-8.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erridge C, Stewart J, Bennett-Guerrero E, McIntosh TJ, Poxton IR. The biological activity of a liposomal complete core lipopolysaccharide vaccine. J Endotoxin Res. 2002;8:39–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pier GB, Thomas DM. Characterization of the human immune response to a polysaccharide vaccine from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Infect Dis. 1983;148:206–213. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cryz SJ, Jr, Sadoff JC, Cross AS, Furer E. Safety and immunogenicity of a polyvalent Pseudomonas aeruginosa O-polysaccharide-toxin A vaccine in humans. Antibiot Chemother. 1989;42:177–183. doi: 10.1159/000417618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seid RC, Jr, Sadoff JC. Preparation and characterization of detoxified lipopolysaccharide-protein conjugates. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:7305–7310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haghbin M, Armstrong D, Murphy ML. Controlled prospective trial of Pseudomonas aeruginosa vaccine in children with acute leukemia. Cancer. 1973;32:761–766. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197310)32:4<761::AID-CNCR2820320405>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pennington JE, Reynolds HY, Wood RE, Robinson RA, Levine AS. Use of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa vaccine in pateints with acute leukemia and cystic fibrosis. Am J Med. 1975;58:629–636. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(75)90498-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Young LS, Meyer RD, Armstrong D. Pseudomonas aeruginosa vaccine in cancer patients. Ann Intern Med. 1973;79:518–527. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-79-4-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alexander JW, Fisher MW, MacMillan BG. Immunological control of Pseudomonas infection in burn patients: a clinical evaluation. Arch Surg. 1971;102:31–35. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1971.01350010033008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pennington JE. Preliminary investigations of Pseudomonas aeruginosa vaccine in patients with leukemia and cystic fibrosis. J Infect Dis. 1974;130:159–162. doi: 10.1093/infdis/130.Supplement.S159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacIntyre S, McVeigh T, Owen P. Immunochemical and biochemical analysis of the polyvalent Pseudomonas aeruginosa vaccine PEV. Infect Immun. 1986;51:675–686. doi: 10.1128/iai.51.2.675-686.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langford DT, Hiller J. Prospective, controlled study of a polyvalent pseudomonas vaccine in cystic fibrosis—three year results. Arch Dis Child. 1984;59:1131–1134. doi: 10.1136/adc.59.12.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones RJ, Roe EA, Gupta JL. Low mortality in burned patients in a Pseudomonas vaccine trial. Lancet. 1978;2:401–403. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(78)91868-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones RJ, Roe EA, Gupta JL. Controlled trials of a polyvalent pseudomonas vaccine in burns. Lancet. 1979;2:977–982. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(79)92559-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones RJ, Roe EA, Gupta JL. Controlled trial of Pseudomonas immunoglobulin and vaccine in burn patients. Lancet. 1980;2:1263–1265. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(80)92334-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cryz SJ, Jr, Furer E, Cross AS, Wegmann A, Germanier R, Sadoff JC. Safety and immunogenicity of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa O-polysaccharide toxin A conjugate vaccine in humans. J Clin Invest. 1987;80:51–56. doi: 10.1172/OCI113062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cryz SJ, Jr, Lang A, Rudeberg A, Wedgwood J, Que JU, Furer E, et al. Immunization of cystic fibrosis patients with a Pseudomonas aeruginosa O-polysaccharide-toxin A conjugate vaccine. Behring Inst Mitt. 1997;98:345–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cryz SJ, Jr, Sadoff JC, Furer E. Immunization with a Pseudomonas aeruginosa immunotype 5 O polysaccharide-toxin A conjugate vaccine: effect of a booster dose on antibody levels in humans. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1829–1830. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.7.1829-1830.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cryz SJ, Jr, Sadoff JC, Ohman D, Furer E. Characterization of the human immune response to a Pseudomonas aeruginosa O-polysaccharide-toxin A conjugate vaccine. J Lab Clin Med. 1988;111:701–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cryz SJ, Jr, Wedgwood J, Lang AB, Ruedeberg A, Que JU, Furer E, et al. Immunization of noncolonized cystic fibrosis patients against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:1159–1162. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.5.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lang AB, Rudeberg A, Schoni MH, Que JU, Furer E, Schaad UB. Vaccination of cystic fibrosis patients against Pseudomonas aeruginosa reduces the proportion of patients infected and delays time to infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:504–510. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000129688.50588.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hatano K, Boisot S, DesJardins D, Wright DC, Brisker J, Pier GB. Immunogenic and antigenic properties of a heptavalent high-molecular-weight O-polysaccharide vaccine derived from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3608–3616. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3608-3616.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hatano K, Pier GB. Complex serology and immune response of mice to variant high-molecular-weight O polysaccharides isolated from Pseudomonas aeruginosa serogroup O2 strains. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3719–3726. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3719-3726.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pier GB. Rationale for development of immunotherapies that target mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis patients. Behring Inst Mitt. 1997;98:350–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hogardt M, Heesemann J. Adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa during persistence in the cystic fibrosis lung. Int J Med Microbiol. 2010;300:557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pier GB, DesJardin D, Grout M, Garner C, Bennett SE, Pekoe G, et al. Human immune response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa mucoid exopolysaccharide (alginate) vaccine. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3972–3979. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3972-3979.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pier GB, Matthews WJ, Jr, Eardley DD. Immunochemical characterization of the mucoid exopolysaccharide of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Infect Dis. 1983;147:494–503. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.3.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yushkova NA, Kholodkova EV, Korobova TS, Stanislavsky ES. Serologic and protective cross-reactivity of antisera to Pseudomonas aeruginosa extracellular slime glycolipoprotein. Acta Microbiol Hung. 1986;33:147–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pier GB, Saunders JM, Ames P, Edwards MS, Auerbach H, Goldfarb J, et al. Opsonophagocytic killing antibody to Pseudomonas aeruginosa mucoid exopolysaccharide in older noncolonized patients with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:793–798. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198709243171303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pier GB, Small GJ, Warren HB. Protection against mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in rodent models of endobronchial infections. Science. 1990;249:537–540. doi: 10.1126/science.2116663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cryz SJ, Jr, Furer E, Que JU. Synthesis and characterization of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate-toxin A conjugate vaccine. Infect Immun. 1991;59:45–50. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.1.45-50.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kashef N, Behzadian-Nejad Q, Najar-Peerayeh S, Mousavi-Hosseini K, Moazzeni M, Djavid GE. Synthesis and characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate-tetanus toxoid conjugate. J Med Microbiol. 2006;55:1441–1446. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46696-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Theilacker C, Coleman FT, Mueschenborn S, Llosa N, Grout M, Pier GB. Construction and characterization of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa mucoid exopolysaccharide-alginate conjugate vaccine. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3875–3884. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.7.3875-84.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Buret A, Dunkley M, Clancy RL, Cripps AW. Effector mechanisms of intestinally induced immunity to Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the rat lung: role of neutrophils and leukotriene B4. Infect Immun. 1993;61:671–679. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.671-679.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buret A, Dunkley ML, Pang G, Clancy RL, Cripps AW. Pulmonary immunity to Pseudomonas aeruginosa in intestinally immunized rats roles of alveolar macrophages, tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1alpha. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5335–5343. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5335-5343.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dunkley ML, Rajyaguru S, McCue A, Cripps AW, Kyd JM. Pseudomonas aeruginosa-specific IgG1 and IgG2 subclasses in enhancement of pulmonary clearance following passive immunisation in the rat. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;39:37–44. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cripps AW, Dunkley ML, Clancy RL, Kyd J. Vaccine strategies against Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in the lung. Behring Inst Mitt. 1997;98:262–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cripps AW, Peek K, Dunkley M, Vento K, Marjason JK, McIntyre ME, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an oral inactivated whole-cell Pseudomonas aeruginosa vaccine administered to healthy human subjects. Infect Immun. 2006;74:968–974. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.2.968-74.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kamei A, Coutinho-Sledge YS, Goldberg JB, Priebe GP, Pier GB. Mucosal vaccination with a multivalent, live-attenuated vaccine induces multifactorial immunity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa acute lung infection. Infect Immun. 2011;79:1289–1299. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01139-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Priebe GP, Brinig MM, Hatano K, Grout M, Coleman FT, Pier GB, et al. Construction and characterization of a live, attenuated aroA deletion mutant of Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a candidate intranasal vaccine. Infect Immun. 2002;70:1507–1517. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.3.1507-17.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Priebe GP, Walsh RL, Cederroth TA, Kamei A, Coutinho-Sledge YS, Goldberg JB, et al. IL-17 is a critical component of vaccine-induced protection against lung infection by lipopolysaccharide-heterologous strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Immunol. 2008;181:4965–4975. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Priebe GP, Meluleni GJ, Coleman FT, Goldberg JB, Pier GB. Protection against fatal Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia in mice after nasal immunization with a live, attenuated aroA deletion mutant. Infect Immun. 2003;71:1453–1461. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1453-61.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zaidi TS, Priebe GP, Pier GB. A live-attenuated Pseudomonas aeruginosa vaccine elicits outer membrane protein-specific active and passive protection against corneal infection. Infect Immun. 2006;74:975–983. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.2.975-83.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sirard JC, Niedergang F, Kraehenbuhl JP. Live attenuated Salmonella: a paradigm of mucosal vaccines. Immunol Rev. 1999;171:5–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1999.tb01340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baud D, Benyacoub J, Revaz V, Kok M, Ponci F, Bobst M, et al. Immunogenicity against human papillomavirus type 16 virus-like particles is strongly enhanced by the PhoPc phenotype in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect Immun. 2004;72:750–756. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.2.750-6.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fouts TR, DeVico AL, Onyabe DY, Shata MT, Bagley KC, Lewis GK, et al. Progress toward the development of a bacterial vaccine vector that induces high-titer long-lived broadly neutralizing antibodies against HIV-1. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;37:129–134. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Metzger WG, Mansouri E, Kronawitter M, Diescher S, Soerensen M, Hurwitz R, et al. Impact of vector-priming on the immunogenicity of a live recombinant Salmonella enterica serovar typhi Ty21a vaccine expressing urease A and B from Helicobacter pylori in human volunteers. Vaccine. 2004;22:2273–2277. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ward SJ, Douce G, Figueiredo D, Dougan G, Wren BW. Immunogenicity of a Salmonella typhimurium aroA aroD vaccine expressing a nontoxic domain of Clostridium difficile toxin A. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2145–2152. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2145-2152.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.DiGiandomenico A, Rao J, Goldberg JB. Oral vaccination of BALB/c mice with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium expressing Pseudomonas aeruginosa O antigen promotes increased survival in an acute fatal pneumonia model. Infect Immun. 2004;72:7012–7021. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.12.7012-21.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.DiGiandomenico A, Rao J, Harcher K, Zaidi TS, Gardner J, Neely AN, et al. Intranasal immunization with heterologously expressed polysaccharide protects against multiple Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4624–4629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608657104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bumann D, Behre C, Behre K, Herz S, Gewecke B, Gessner JE, et al. Systemic, nasal and oral live vaccines against Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a clinical trial of immunogenicity in lower airways of human volunteers. Vaccine. 2010;28:707–713. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arora SK, Ritchings BW, Almira EC, Lory S, Ramphal R. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa flagellar cap protein, FliD, is responsible for mucin adhesion. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1000–1007. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1000-1007.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cobb LM, Mychaleckyj JC, Wozniak DJ, Lopez-Boado YS. Pseudomonas aeruginosa flagellin and alginate elicit very distinct gene expression patterns in airway epithelial cells: implications for cystic fibrosis disease. J Immunol. 2004;173:5659–5670. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ramphal R, Guay C, Pier GB. Pseudomonas aeruginosa adhesins for tracheobronchial mucin. Infect Immun. 1987;55:600–603. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.3.600-603.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gewirtz AT, Navas TA, Lyons S, Godowski PJ, Madara JL. Cutting edge: bacterial flagellin activates basolaterally expressed TLR5 to induce epithelial proinflammatory gene expression. J Immunol. 2001;167:1882–1885. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rosok MJ, Stebbins MR, Connelly K, Lostrom ME, Siadak AW. Generation and characterization of murine antiflagellum monoclonal antibodies that are protective against lethal challenge with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3819–3828. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.12.3819-3828.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Holder IA, Wheeler R, Montie TC. Flagellar preparations from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: animal protection studies. Infect Immun. 1982;35:276–280. doi: 10.1128/iai.35.1.276-280.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Holder IA, Naglich JG. Experimental studies of the pathogenesis of infections due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa: immunization using divalent flagella preparations. J Trauma. 1986;26:118–122. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198602000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Landsperger WJ, Kelly-Wintenberg KD, Montie TC, Knight LS, Hansen MB, Huntenburg CC, et al. Inhibition of bacterial motility with human antiflagellar monoclonal antibodies attenuates Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced pneumonia in the immunocompetent rat. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4825–4830. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4825-4830.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Oishi K, Sonoda F, Iwagaki A, Ponglertnapagorn P, Watanabe K, Nagatake T, et al. Therapeutic effects of a human antiflagella monoclonal antibody in a neutropenic murine model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:164–170. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.2.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Doring G, Pfeiffer C, Weber U, Mohr-Pennert A, Dorner F. Parenteral application of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa flagella vaccine elicits specific anti-flagella antibodies in the airways of healthy individuals. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:983–985. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.4.7697276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Doring G, Meisner C, Stern M. A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled phase III study of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa flagella vaccine in cystic fibrosis patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11020–11025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702403104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Saha S, Takeshita F, Matsuda T, Jounai N, Kobiyama K, Matsumoto T, et al. Blocking of the TLR5 activation domain hampers protective potential of flagellin DNA vaccine. J Immunol. 2007;179:1147–1154. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Campodonico VL, Llosa NJ, Grout M, Doring G, Maira-Litran T, Pier GB. Evaluation of flagella and flagellin of Pseudomonas aeruginosa as vaccines. Infect Immun. 2010;78:746–755. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00806-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tart AH, Blanks MJ, Wozniak DJ. The AlgT-dependent transcriptional regulator AmrZ (AlgZ) inhibits flagellum biosynthesis in mucoid, nonmotile Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis isolates. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:6483–6489. doi: 10.1128/JB.00636-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Castric PA, Deal CD. Differentiation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pili based on sequence and B-cell epitope analyses. Infect Immun. 1994;62:371–376. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.371-376.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kus JV, Tullis E, Cvitkovitch DG, Burrows LL. Significant differences in type IV pilin allele distribution among Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis (CF) versus non-CF patients. Microbiology. 2004;150:1315–1326. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26822-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Spangenberg C, Fislage R, Sierralta W, Tummler B, Romling U. Comparison of type IV-pilin genes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa of various habitats has uncovered a novel unusual sequence. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;127:158. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bryan R, Kube D, Perez A, Davis P, Prince A. Overproduction of the CFTR R domain leads to increased levels of asialoGM1 and increased Pseudomonas aeruginosa binding by epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;19:269–277. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.19.2.2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Audette GF, Irvin RT, Hazes B. Crystallographic analysis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain K122-4 monomeric pilin reveals a conserved receptor-binding architecture. Biochemistry. 2004;43:11427–11435. doi: 10.1021/bi048957s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hazes B, Sastry PA, Hayakawa K, Read RJ, Irvin RT. Crystal structure of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAK pilin suggests a main-chain-dominated mode of receptor binding. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:1005–1017. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Keizer DW, Slupsky CM, Kalisiak M, Campbell AP, Crump MP, Sastry PA, et al. Structure of a pilin monomer from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: implications for the assembly of pili. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24186–24193. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100659200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sheth HB, Glasier LM, Ellert NW, Cachia P, Kohn W, Lee KK, et al. Development of an anti-adhesive vaccine for Pseudomonas aeruginosa targeting the C-terminal region of the pilin structural protein. Biomed Pept Proteins Nucleic Acids. 1995;1:141–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Umelo-Njaka E, Nomellini JF, Bingle WH, Glasier LG, Irvin RT, Smith J. Expression and testing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa vaccine candidate proteins prepared with the Caulobacter crescentus S-layer protein expression system. Vaccine. 2001;19:1406–1415. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(00)00362-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ohama M, Hiramatsu K, Miyajima Y, Kishi K, Nasu M, Kadota J. Intratracheal immunization with pili protein protects against mortality associated with Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia in mice. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2006;47:107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hertle R, Mrsny R, Fitzgerald DJ. Dual-function vaccine for Pseudomonas aeruginosa: characterization of chimeric exotoxin A-pilin protein. Infect Immun. 2001;69:6962–6969. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.11.6962-9.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.DiGiandomenico A, Matewish MJ, Bisaillon A, Stehle JR, Lam JS, Castric P. Glycosylation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa 1244 pilin: glycan substrate specificity. Mol Microbiol. 2002;46:519–530. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Smedley JG, 3rd, Jewell E, Roguskie J, Horzempa J, Syboldt A, Stolz DB, et al. Influence of pilin glycosylation on Pseudomonas aeruginosa 1244 pilus function. Infect Immun. 2005;73:7922–7931. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.7922-31.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Horzempa J, Held TK, Cross AS, Furst D, Qutyan M, Neely AN, et al. Immunization with a Pseudomonas aeruginosa 1244 pilin provides O-antigen-specific protection. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:590–597. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00476-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cachia PJ, Glasier LM, Hodgins RR, Wong WY, Irvin RT, Hodges RS. The use of synthetic peptides in the design of a consensus sequence vaccine for Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Pept Res. 1998;52:289–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1998.tb01243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cachia PJ, Hodges RS. Synthetic peptide vaccine and antibody therapeutic development: prevention and treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biopolymers. 2003;71:141–168. doi: 10.1002/bip.10395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Campbell AP, Wong WY, Houston M, Jr, Schweizer F, Cachia PJ, Irvin RT, et al. Interaction of the receptor binding domains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pili strains PAK PAO, KB7 and P1 to a cross-reactive antibody and receptor analog: implications for synthetic vaccine design. J Mol Biol. 1997;267:382–402. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hackbarth C, Hodges RS. Synthetic peptide vaccine development: designing dual epitopes into a single pilin peptide immunogen generates antibody cross-reactivity between two strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2010;76:293–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2010.01021.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kao DJ, Churchill ME, Irvin RT, Hodges RS. Animal protection and structural studies of a consensus sequence vaccine targeting the receptor binding domain of the type IV pilus of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Mol Biol. 2007;374:426–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kao DJ, Hodges RS. Advantages of a synthetic peptide immunogen over a protein immunogen in the development of an anti-pilus vaccine for Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2009;74:33–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2009.00825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sawa T, Yahr TL, Ohara M, Kurahashi K, Gropper MA, Wiener-Kronish JP, et al. Active and passive immunization with the Pseudomonas V antigen protects against type III intoxication and lung injury. Nat Med. 1999;5:392–398. doi: 10.1038/7391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Holder IA, Neely AN, Frank DW. PcrV immunization enhances survival of burned Pseudomonas aeruginosa-infected mice. Infect Immun. 2001;69:5908–5910. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5908-10.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Markham AP, Barrett BS, Esfandiary R, Picking WL, Picking WD, Joshi SB, et al. Formulation and immunogenicity of a potential multivalent type III secretion system-based protein vaccine. J Pharm Sci. 2010;99:4497–4509. doi: 10.1002/jps.22195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chen TY, Lin CP, Loa CC, Chen TL, Shang HF, Hwang J, et al. A nontoxic Pseudomonas exotoxin A induces active immunity and passive protective antibody against Pseudomonas exotoxin A intoxication. J Biomed Sci. 1999;6:357–363. doi: 10.1007/BF02253525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Denis-Mize KS, Price BM, Baker NR, Galloway DR. Analysis of immunization with DNA encoding Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2000;27:147–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2000.tb01425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Shiau JW, Tang TK, Shih YL, Tai C, Sung YY, Huang JL, et al. Mice immunized with DNA encoding a modified Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A develop protective immunity against exotoxin intoxication. Vaccine. 2000;19:1106–1112. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(00)00335-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Manafi A, Kohanteb J, Mehrabani D, Japoni A, Amini M, Naghmachi M, et al. Active immunization using exotoxin A confers protection against Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in a mouse burn model. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Doring G, Dalhoff A, Vogel O, Brunner H, Droge U, Botzenhart K. In vivo activity of proteases of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a rat model. J Infect Dis. 1984;149:532–537. doi: 10.1093/infdis/149.4.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Fick RB, Jr, Baltimore RS, Squier SU, Reynolds HY. IgG proteolytic activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:589–598. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Parmely M, Gale A, Clabaugh M, Horvat R, Zhou WW. Proteolytic inactivation of cytokines by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3009–3014. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.9.3009-3014.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Horvat RT, Parmely MJ. Pseudomonas aeruginosa alkaline protease degrades human gamma interferon and inhibits its bioactivity. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2925–2932. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.11.2925-2932.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kharazmi A, Eriksen HO, Doring G, Goldstein W, Hoiby N. Effect of Pseudomonas aeruginosa proteases on human leukocyte phagocytosis and bactericidal activity. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand [C] 1986;94:175–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1986.tb02108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Theander TG, Kharazmi A, Pedersen BK, Christensen LD, Tvede N, Poulsen LK, et al. Inhibition of human lymphocyte proliferation and cleavage of interleukin-2 by Pseudomonas aeruginosa proteases. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1673–1677. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.7.1673-1677.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Pedersen BK, Kharazmi A. Inhibition of human natural killer cell activity by Pseudomonas aeruginosa alkaline protease and elastase. Infect Immun. 1987;55:986–989. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.4.986-989.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Homma JY, Abe C, Tanamoto K, Hirao Y, Morihara K, Tsuzuki H, et al. Effectiveness of immunization with single and multi-component vaccines prepared from a common antigen (OEP), protease and elastase toxoids of Pseudomonas aeruginosa on protection against hemorrhagic pneumonia in mink due to P. aeruginosa. Jpn J Exp Med. 1978;48:111–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hirao Y, Homma JY. Therapeutic effect of immunization with OEP, protease toxoid and elastase toxoid on corneal ulcers in mice due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Jpn J Exp Med. 1978;48:41–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kawaharajo K, Homma JY. Effects of elastase, protease and common antigen (OEP) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa on protection against burns in mice. Jpn J Exp Med. 1977;47:495–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sokol PA, Kooi C, Hodges RS, Cachia P, Woods DE. Immunization with a Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase peptide reduces severity of experimental lung infections due to P. aeruginosa Or Burkholderia cepacia. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1682–1692. doi: 10.1086/315470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Matsumoto T, Tateda K, Furuya N, Miyazaki S, Ohno A, Ishii Y, et al. Efficacies of alkaline protease, elastase and exotoxin A toxoid vaccines against gut-derived Pseudomonas aeruginosa sepsis in mice. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:303–308. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-4-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Saha S, Takeshita F, Sasaki S, Matsuda T, Tanaka T, Tozuka M, et al. Multivalent DNA vaccine protects mice against pulmonary infection caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Vaccine. 2006;24:6240–6249. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Mutharia LM, Hancock RE. Surface localization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane porin protein F by using monoclonal antibodies. Infect Immun. 1983;42:1027–1033. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.3.1027-1033.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Mutharia LM, Nicas TI, Hancock RE. Outer membrane proteins of Pseudomonas aeruginosa serotype strains. J Infect Dis. 1982;146:770–779. doi: 10.1093/infdis/146.6.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Gilleland HE, Jr, Gilleland LB, Matthews-Greer JM. Outer membrane protein F preparation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a vaccine against chronic pulmonary infection with heterologous immunotype strains in a rat model. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1017–1022. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.5.1017-1022.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Matthews-Greer JM, Gilleland HE., Jr Outer membrane protein F (porin) preparation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a protective vaccine against heterologous immunotype strains in a burned mouse model. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:1282–1291. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.6.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Price BM, Barten Legutki J, Galloway DR, von Specht BU, Gilleland LB, Gilleland HE, Jr, et al. Enhancement of the protective efficacy of an oprF DNA vaccine against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2002;33:89–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2002.tb00577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Price BM, Galloway DR, Baker NR, Gilleland LB, Staczek J, Gilleland HE., Jr Protection against Pseudomonas aeruginosa chronic lung infection in mice by genetic immunization against outer membrane protein F (OprF) of P. aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 2001;69:3510–3515. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3510-5.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Finke M, Duchene M, Eckhardt A, Domdey H, von Specht BU. Protection against experimental Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection by recombinant P. aeruginosa lipoprotein I expressed in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2241–2244. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.7.2241-2244.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]