Abstract

Overview

Previous studies on aging and attention to emotional information found that older adults may look away from negative stimuli to regulate their moods. However, it is an open question whether older adults’ tendency to look less at negative material comes at the expense of learning when negative information is also health-relevant. This study investigated how age-related changes in attention to negative but relevant information about skin cancer risk reduction influenced both subsequent health behavior and mood regulation.

Methods

Younger (18-25, n = 78) and older (60-92, n = 77) adults’ fixations toward videos containing negatively-valenced content and risk-reduction information about skin cancer were recorded with eye-tracking. Self-reported mood ratings were measured throughout. Behavioral outcome measures (e.g., answering knowledge questions about skin cancer, choosing a sunscreen, completing a skin self-exam) assessed participants’ learning of key health-relevant information, their interest in seeking additional information, and their engagement in protective behaviors.

Results

Older adults generally looked less at the negative video content, more rapidly regulated their moods, and learned fewer facts about skin cancer; yet, they engaged in a greater number of protective behaviors than did younger adults.

Conclusions

Older adults may demonstrate an efficient looking strategy that extracts important information without disrupting their moods, and they may compensate for less learning by engaging in a greater number of protective behaviors. Younger adults may be distracted by disruptions to their mood, constraining their engagement in protective behaviors.

Keywords: aging, gaze preferences, skin cancer, mood regulation

According to socioemotional selectivity theory (SST: Carstensen, 2006), a limited time perspective motivates older adults to pursue hedonic goals that optimize their affective experience; indeed, older adults report more positive affect than do younger adults (e.g., Carstensen et al., 2011). Building on assertions that older adults might display positivity effects in their information processing to optimize their mood state and regulate their emotions (e.g., Carstensen & Mikels, 2005), several studies observed age differences in attention towards emotionally-valenced stimuli. For example, a dot-probe study found that older adults attend more to positive and less to negative stimuli (Mather & Carstensen, 2003). Several eye-tracking studies found older adults fixate more to positive and less to some types of negative stimuli than do younger adults, across stimulus types (Isaacowitz, Wadlinger, Goren & Wilson, 2006a,b; Isaacowitz & Choi, 2011). Older adults activate positive looking preferences when in bad moods, (Isaacowitz, Toner, Goren, & Wilson, 2008), and these looking preferences can lead to better moods, though only for older adults with good executive functioning (Isaacowitz, Toner, & Neupert, 2009; Noh, Lohani & Isaacowitz, in press). In summary, these findings demonstrate that positive looking can facilitate mood regulation for some older adults in certain situations.

Is There a Mood-Health Behavior Trade-off with Aging?

The strong version of SST suggests that older adults’ positive looking might lead them to ignore negative health information in order to maintain positive affect. Several studies have linked age-related positivity effects to the processing of health information: for example, Löckenhoff & Carstensen (2007) found that older adults showed positivity in how they reviewed health-related information unless they were given information-gathering goals. In another study, older adults remembered a higher proportion of positive messages, rated positive pamphlets as more informative than negative ones, and misremembered negative messages to be positive, demonstrating positivity effects for health care messages (Shamaskin, Mikels, & Reed, 2010).

But not everything negative in the environment should be ignored: for example, public health warnings often contain negative but important information. While experience sampling work supports the SST prediction that older adults prioritize hedonic goals (Riediger, Schmiedek, Wagner, & Lindenberger, 2009), it remains unclear as to whether older adults would prioritize their feelings at the expense of attending to important health information. Recently, Mikels et al. (2010) evaluated decision quality in the context of health information when younger and older adults were instructed to focus on either their emotions or on information. Whereas the informational instructions led to the best decision quality in younger adults, older adults actually performed better under the emotional instructions. While this finding suggests that there may not be a trade-off between regulating emotions and processing health information for older adults, the outcome measure in that study involved health-related choices rather than behavior based on health information presented; moreover, the valence of the material was not varied systematically. Therefore, the current study represents the first attempt (to our knowledge) to link positivity in attention directly to regulation of both mood and health behavior.

Skin Cancer: Psychological and Behavioral Components

We focused on information and behavior related to skin cancer (melanoma) for two reasons. First, skin cancer is a serious public health concern with a clear behavioral component that affects both younger and older adults. Risky behaviors (e.g., failing to use sunscreen) are highest among individuals ages 18-29, but incidence rates for melanoma increase with age, with death rates at 70.4 per 100,000 among adults age 65 and over (Altekruse et al., 2010). Skin cancer can be preventable (Glanz & Mayer, 2005), yet a large segment of the population do not engage in protective behaviors, such as annual skin self-exams (Kasparian et al., 2009), providing an opportunity for behavioral interventions that seem to be effective within the general population (e.g., Weinstock et al., 2007) and in individuals with moderate to high risk for skin cancer (e.g., Glanz, Schoenfeld, & Steffen, 2010). Second, paying attention is a critical part of skin cancer risk reduction (e.g., identifying abnormal moles while conducting skin self-exams) making eye tracking especially appropriate (e.g., Isaacowitz, 2005; Luo & Isaacowitz, 2007).

The Current Study

Would a more positive looking pattern, indicated by avoiding the negative aspects of skin cancer information, lead older adults to have better moods, but at the expense of learning and acting on the health-relevant messages? To determine whether such a mood-health behavior trade-off might exist for older adults, the current study aimed to assess looking patterns toward skin cancer information relevant to both younger and older adults. Younger and older adults’ eye fixations to videos about skin cancer that contained some negatively-valenced content were measured using eye-tracking. We assessed changes in knowledge and self-rated mood as a function of watching the videos.

Health behaviors related to skin cancer risk-reduction were also considered; these measures were somewhat exploratory attempts to derive behavioral indices of the extent to which attending to the presented information might lead to interest in engaging in protective behaviors and learning more about how to reduce skin cancer risk. Expanding on behavioral measures used previously in general health psychology research (e.g., Dunlop, Wakefield, & Kashima, 2010) and in studies of skin cancer behavior specifically (e.g., Speelman, Martin, Flower, & Simpson, 2010), health behavior measures included amount of time browsing web pages containing information on skin cancer risk-reduction (as opposed to unrelated sites), choice of take-home items that would provide greater information about skin cancer and help conduct a skin self-exam, selection of the most protective sunscreen over a less desirable lotion choice, as well as likelihood of completing and returning a skin self-exam after leaving the lab.

In our previous work, we found that age differences in fixation to negative stimuli, and to some extent in how these looking patterns predict mood change, are most pronounced in contexts in which mood regulation is salient, either implicitly (Isaacowitz et al., 2008) or explicitly (Noh, Lohani, & Isaacowitz, in press). In other work, emotional goals have produced better performance by older adults, whereas informational goals led to better performance by younger adults in health-related decision making (Mikels et al., 2010). Therefore, it seemed important to vary the instructions to determine if emotion- or information-oriented instructions might change fixation-mood-behavior links. We hypothesized that age differences would be most pronounced in the condition in which participants were instructed to focus on regulating their moods; prioritizing emotion regulation was expected to lead to the most positivity in looking patterns (e.g., looking less at the most negatively-valenced parts of the videos) and the best mood regulation outcomes for older than younger adults. If this looking-mood pattern is also associated with fewer health-related behaviors, that would be indicative of a mood-health behavior trade-off for older adults trying to regulate their emotions. In the information-focused condition, we expected fewer differences between younger and older adults in fixation to the negative and similar patterns in health behavior. The natural viewing (control) condition was expected to show an intermediate pattern, as older adults were expected to focus naturally on material that would help them feel good at the expense of acquiring risk-reduction health information, though to a lesser degree than when focused on regulating emotions.

Method

Participants

For consistency with our previous studies of age differences in attention, we used the same age ranges as in that past work: younger (ages 18-25 years) and older (ages 60-92 years) adult participants were recruited from campus and the surrounding community. Data from 10 younger and 18 older adults were excluded from all analyses due to trackability issues (e.g., occluded pupils), incomplete data, or manipulation failures (see Procedure section). The total sample consisted of 78 younger (Mage = 19.5, 64.1% women) and 77 older (Mage = 71.6, 81.8% women) adults. Participants were healthy and mobile enough to transport themselves to the lab for the experiment. Most of the younger adults received course credits and the remaining younger and older adults were paid $20 for their participation.

Study Design

The basic study had a 2 (age group: younger, older adults) × 3 (instruction group: control, emotion-focused, information-focused) between-subjects design. Fixation type (extremely negative, less negative, informative), time of mood measurement, and change in knowledge from before to after the video were within-subjects variables.

Measures

Knowledge and relevance of skin cancer

Knowledge about skin cancer was assessed using twenty items based on key information presented in the videos (e.g., “Skin cancer is the most common form of cancer within what age bracket?”) before and at the end of the experiment. Higher scores indicate greater skin cancer knowledge (max. score = 20). The Brief Skin Cancer Risk Assessment Tool (BRAT; Glanz et al., 2003) measured each participant's actual, objective risk of developing skin cancer; higher scores indicate greater risk (max. score = 89). We also assessed whether and how frequently participants did skin self-exams (Weinstock et al., 2004).

Executive functioning

The Attention Network Test (ANT; Fan et al., 2002) measures individual differences in the efficiency of alerting, orienting, and conflict network. The conflict effect score assesses executive control; lower scores indicate better executive functioning.

Fixation Measures and Materials

Video presentation of health-relevant information

The first video, “Sunburnt Country” (60 Minutes Australia, 13.5 min) follows Ben (age 17) and Renee (age 24) who survive successful melanoma treatment, whereas Steven (age 28) and John (age 57) have only a few months left to live due to malignant metastasis. Graphic images of scars, surgery scenes, and personal stories vividly illustrate the seriousness and deadly potential of melanoma. This video was shown first to increase awareness about the risk of melanoma for all age groups.

The second video, “Check it out: Why and How to do Skin Self-Exam” (Weinstock et al., 2007, 14 min) then showed how to reduce skin cancer risk. This video presents skin cancer risk information, instructions on how to conduct skin self-exams, as well as testimonials from survivors who caught their melanoma early through regular skin self-exams.

Viewing instructions

Participants were randomly assigned to one of three viewing instruction groups. Participants in the control group were asked to view the videos “naturally, as if you were watching television at home.” Participants in the emotion-focused group were asked to view the videos “with the goal of managing your emotions and avoiding feeling bad as much as you can.” Participants in the information-focused group were asked to view the videos “with the goal of getting as much information as possible and to be as thorough as you can in collecting information so that you can act later based on what you have learned.” At the end of the session, participants were asked to recall their viewing instructions as a manipulation check. Only those who recalled the instructions correctly (91.2%) were included in the analyses.

Eye-tracking and equipment

An ASL (Applied Science Labs, Bedford, MA) EYETRAC 6 Desktop Video Head Tracking eye-tracker with facial recognition and GazeTracker software (Eye-Tellect, LLC., Charlottesville, VA) recorded participants’ eye fixations at a rate of 60 Hz. A 17-point calibration procedure at the beginning of each eye tracking session ensured gaze accuracy to within 1° visual angle. Visual stimuli were presented on a 19-inch flat-panel LCD wide-monitor display with a 1440 × 960 dpi screen resolution. Both videos were presented at 75% of the screen size, centered on the screen with a blue border so that participants could look away from the video without interrupting eye-tracking.

LookZone creation and ratings of valence, arousal, and informativeness

Using GazeTracker, we created LookZones (LZs) around what appeared to be extremely negative (e.g., John's amputated shoulder covered in melanoma), less negative (e.g., Ben discussing how his frequent, long days at the beach increased his risk for developing melanoma), and informative areas (e.g., a dermatologist discussing why checking one's skin monthly is critical for early detection). To verify this classification of the LZs, 16 raters (who were unaware of the study's design) rated pre-specified intervals containing these LZs, on each interval's valence, arousal, and informativeness of skin-cancer material, using 7-point response scales; higher rating scores indicate more positive valence, higher arousal, and greater communication of skin cancer information. Extremely negative LZs had valence ratings of 2.5 or lower (M = 1.81), were highly arousing (M = 5.27) and not informative (M = 3.31). Less negative LZs had valence ratings between 2.5 and 4.5 (M = 3.53), informative ratings between 3 and 5 (M = 4.45), and were moderately arousing (M = 3.99). Informative LZs had informative ratings of 5 or higher (M = 5.91), were less negative in valence (M = 3.58) and moderately arousing (M = 3.95). Considering the video as a whole, “Sunburnt Country” was more negatively valenced (M = 2.73, t(15) = -6.58, p < .001), more arousing (M = 4.65, t(15) = 5.90, p < .001), and less informative about skin cancer (M = 3.58, t(15) = -8.32, p < .001) than “Check it out,” which was neutral in valence (M = 3.62), less arousing (M = 3.86) and more informative about skin cancer (M = 5.11).

Mood Measures

We recorded self-reported mood using a potentiometer slider (0, worst to 100, best) seven times: 1) at the start of the experiment, 2) at the start and 3) the end of “Sunburnt Country”, 4) at the start and 5) the end of “Check It Out”, 6) after the mole rating, and 7) after web browsing.

Behavioral Outcomes

Mole image ratings

This rating task tested participants’ ability to evaluate moles by applying what they have learned about the warning signs of melanoma. Twenty-two images of melanoma and normal moles were used. Some were collected from publicly available images on the internet; others were taken from a previous study about skin cancer (Luo & Isaacowitz, 2007). Participants practiced using two melanoma and two normal images, then completed the real test using eight melanoma and eight normal mole images (presented in a random order). Ratings were recorded (using a 6-pt scale, where 1 = no concern, 6 = very high concern about melanoma in the mole images) and averaged separately for melanoma and normal moles.

Web browsing behavior and time

To measure their interest in obtaining further information about skin cancer, participants were instructed to browse among five websites for five minutes and to “feel free to spend as much or as little time on these sites as you'd like. There is no obligation to look at all of them.” Three skin cancer-related sites were adapted from the Skin Cancer Foundation's website (www.skincancer.org). The other two were unrelated to skin cancer (healthy eating habits, being environmentally friendly). Each site was listed with a short description to aid participants’ choices. The websites were pre-rated as equally interesting and similar in length. Time spent browsing skin cancer-related sites vs. unrelated sites was recorded. Relative time on the skin cancer sites indicated interest in learning more about skin cancer.

Give-away items

To assess behavioral interest in engaging in sun-protective and skin-checking behaviors, sunscreens in SPFs of 15, 30, and 50 and a lotion with no SPF, pamphlets on melanoma (from the American Cancer Society), reminder magnets, mirrors, body maps and self-skin exam checklists were offered at the end of the study. Participants could choose as many items as they wished, but only 1 item per category (e.g., only 1 sunscreen out of four offered). Choosing a sunscreen with SPF 30 or 50 was indicative of behavioral intention to reduce skin cancer risk in line with the presented information, as was choosing a greater number of these items (across the categories).

Skin self-exam materials

Participants were given a body map (from the American Academy of Dermatology) and a checklist (transcribed from “Check It Out,” Weinstock et al., 2007) and asked to complete a skin self-exam within 1 week of their experimental session, as a follow-up measure of their continued interest in engaging in skin exams as recommended. If they chose to examine their skin, then participants were asked to return their body map using a pre-addressed and stamped envelope. We recorded whether participants returned the skin self-exam. The completion of a self-skin exam provided an indicator of continued interest in engaging in health behaviors protective against skin cancer.

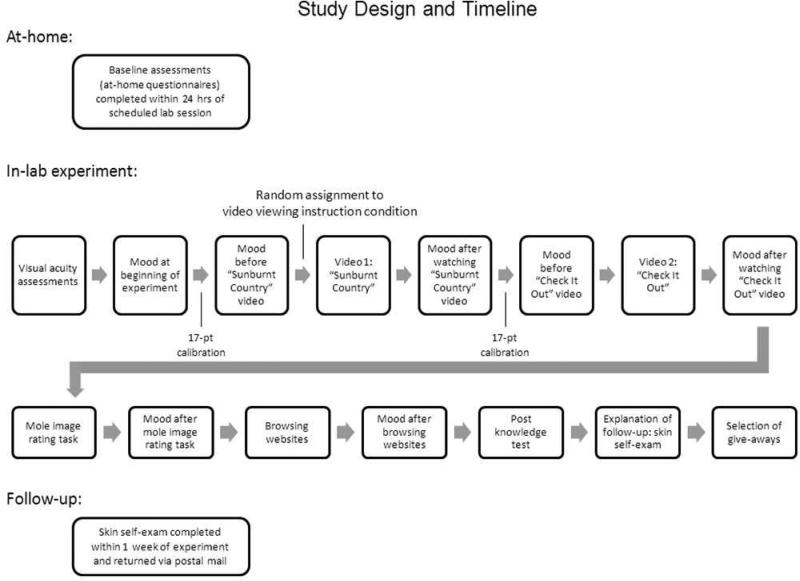

Procedure

The timeline of the study is shown in Figure 1. Participants completed baseline questionnaires within one day of coming to the lab. Once in the lab, after providing informed consent, participants completed vision tests (Pelli, Robson & Wilkins, 1988; Rosenbaum, 1984) to ensure visual acuity and contrast sensitivity for eye tracking. Then, participants watched two videos about skin cancer while having their eyes tracked, and self-reported their moods before and after each video. After watching the videos and recording their mood, participants rated images of moles for level of melanoma concern, based on information presented within the videos. Then, participants spent 5 minutes browsing websites: three were skin-cancer related and two were unrelated. After a final mood rating, participants completed the ANT measure of executive functioning. After the ANT, participants completed a post-experiment knowledge test to indicate how much they had learned from the information in the videos. Then, participants chose from a selection of sunscreens and materials (e.g., hand-held mirror) to help in checking one's skin. Lastly, participants were asked to complete and return a self-skin exam within a week.

Figure 1.

Diagram of study design and timeline of tasks.

General Analytic Strategy

We first tested age and instruction condition differences in fixation to the videos and in mood responses to them. We then examined age and instruction effects on change in skin cancer knowledge and engagement in health-relevant behaviors (i.e., taking relevant give-aways, completing and returning skin self-exam). We also considered whether gender and executive function influenced particular relevant results.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 provides the means and independent t-test results comparing age differences among the demographic, visual acuity, and relevance of skin cancer measures. Both older and younger adults reported “good” or better health at the time of the study, were highly educated (i.e., having attended or attending college), and had adequate visual acuity for the purposes of this study. Both age groups reported similar patterns of sun-protective behaviors before the in-lab session. We repeated all reported analyses including variables with significant age differences as covariates (i.e., personal relevance), but this did not change the main findings as reported.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Measure | Younger adults | Older adults | Age difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic information | |||

| Age | 19.5 (1.6) | 71.7 (7.6) | |

| Years of education | 13.8 (1.1) | 16.1 (2.2) | t(153) = -7.96*** |

| Self-reported health | 3.8 (.9) | 3.8 (.9) | t(153) = -.07 |

| Visual acuity | |||

| Pelli-Robson contrast sensitivity | 1.67 (.09) | 1.55 (.16) | t(152) = 5.14*** |

| Rosenbaum near vision | 21 (3.0) | 30 (16.1) | t(152) = -4.75*** |

| Snellen visual acuity | 25 (8.6) | 33 (13.8) | t(151) = -4.57*** |

| Personal relevance of skin-cancer | |||

| Brief Skin Cancer Risk Assessment Tool (BRAT) | 24.6 (7.8) | 35.4 (17.6) | t(151) = -4.94** |

| Skin-checking behavior (thorough skin examination) | 2.6% | 2.6% | |

| Attention Network Test | |||

| Conflict (Executive control) | 139 | 158 | t(139) = -1.56 |

Note. The sample consisted of 78 young adults (28 men, 50 women; range: 18-25) and 77 older adults (14 men, 63 women; range: 60-92). Means are given for trackable participants only (see Method). Standard deviations are noted within parentheses. The following tests were used: self-reported age, estimated years of education ranging from 10 (some high school) to 18 (graduate school) based on self-reported levels of education, self-reported current health, ranging from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent), Pelli-Robson contrast sensitivity chart (Pelli, Robson & Wilkins, 1988), Rosenbaum pocket vision screener for near vision (Rosenbaum, 1984), Snellen chart for visual acuity, Brief Skin Cancer Risk Assessment Tool (BRAT; Glanz et al., 2003) and Thorough Skin Self-Examination (TSSE; Weinstock et al., 2004). Missing responses are due to technical failures or participants not complying with task instructions for proper assessment. Significance notation indicates significance of the age difference

p < .001.

p < .01.

* p < .05.

Fixation

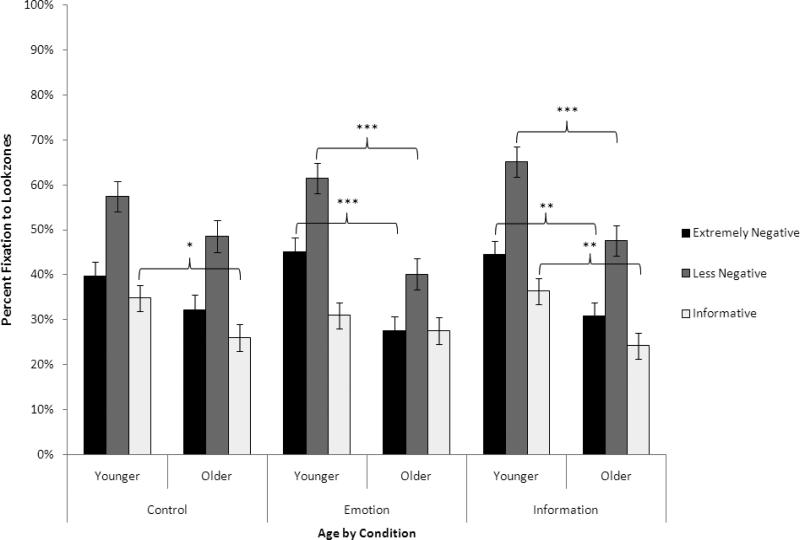

A 3 (fixation type: extremely negative, less negative, informative) × 2 (age group: younger, older) × 3 (instruction group: control, emotion-focused, information-focused) mixed ANOVA assessed the effects of age and instruction on fixation to the different LZs. Generally, there were greater fixations to the less negative than the extremely negative and informative areas, F(2, 146) = 312.93, p < .001, ηp2 = .81, and older adults overall fixated less than did younger adults, F(1, 147) = 28.39, p < .001, ηp2 = .16. There was a significant Age × Fixation interaction, F(2, 146) = 7.29, p = .001, ηp2 = .09, as well as an Age × Instruction Group × Fixation interaction, F(4, 294) = 3.47, p = .009, ηp2 = .05 (see Figure 2 for simple effect analyses). When emotion-focused, older adults looked significantly less towards the extremely and less negative LZs, all ps < .001, but there was no age difference in fixation to the informative LZs, p = .40. When information-focused, older adults looked significantly less at each fixation type than did younger adults, all ps ≤ .003. When viewing naturally, older adults looked significantly less towards the informative LZs, p = .003, but there were no age differences in fixation towards the negative LZs, all ps > .07. There were no other significant effects, ps > .24.

Figure 2.

Mean percent fixation values for each fixation type indicating a significant fixation × age × condition 3-way interaction. Standard errors are represented in the figure by the error bars attached to each point. Significance notation indicates the significance of mean differences between age groups using simple effect analyses: * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

We also tested the effects of fixation type and instruction group separately by age group, to assess whether both younger and older adults modulated their fixation patterns as a function of LZ type and instructions. In younger adults, there was a significant main effect of fixation type, F(2, 73) = 243.62, p < .001, ηp2 = .87 and instruction group, F(2, 74) = 6.52, p = .002, ηp2 = .15, but no interaction, F(4, 148) = 1.47, p = .215. In older adults, there was a significant main effect of fixation type, F(2, 71) = 158.39, p < .001, ηp2 = .82. While the main effect of instruction group was not significant in older adults, F(2, 71) = 1.36, p = .26, there was a significant fixation type × instruction group interaction, F(4, 142) = 3.26, p = .014, ηp2 = .084, suggesting that both age groups did modulate their fixations based on LZ type and instruction.

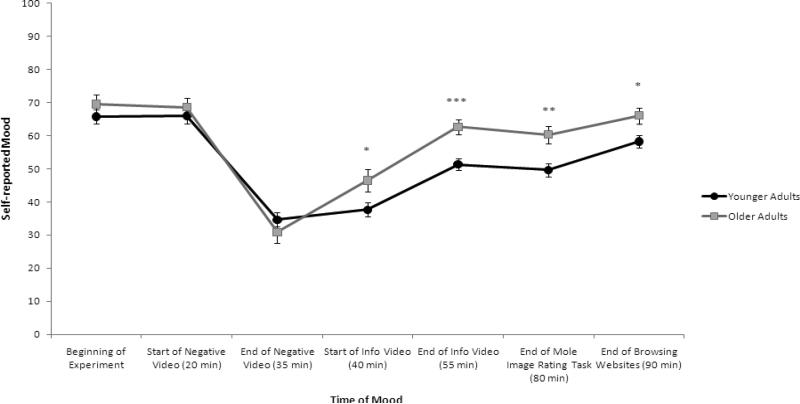

Mood

A 7 (time of mood rating) × 2 (age group: younger, older) × 3 (instruction group: control, emotion-focused, information-focused) mixed ANOVA investigated overall differences among the mood ratings. Participants’ moods generally dropped after watching the negative video, but recovered throughout the experiment, F(6, 125) = 38.53, p < .001, ηp2 = .65. Older adults reported higher moods than did younger adults, F(1, 130) = 5.08, p = .026, ηp2 = .038, but there was a significant Mood × Age interaction, F(6, 125) = 4.17, p = .001, ηp2 = .17, driven by a cubic effect, F(1, 129) = 10.40, p = .002, ηp2 = .075. Figure 3 shows the results of simple contrast analyses investigating this Mood × Age interaction, examining age differences in mood at each time of rating. There were no age differences in moods through the end of the negative video, all ps > .26. However, from the start of the informative video, older adults regulated their moods better than did younger adults, reporting higher moods until the end of the experiment, all ps < .03. There were no effects or interactions with instruction group, all ps > .18.

Figure 3.

Mood trajectories by age and condition. Times noted in parentheses are elapsed time since the beginning of the experiment. Significance notation indicates the significance of the age difference: * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Behavioral Outcomes

Mole image ratings

A 2 (mole type: melanoma, normal) × 2 (age group: younger, older) × 3 (instruction group: control, emotion-focused, information-focused) mixed ANOVA examined the level of concern reflected in the mole image ratings as a function of age and instruction group. Melanoma moles (M = 5.3, SD = .04) were rated to elicit higher concern than normal moles (M = 4.0, SD = .08), F(1, 149) = 480.93, p < .001, ηp2 = .76. Older adults rated all the moles (regardless of type) of higher concern (M = 4.8, SD = .08) than did younger adults (M = 4.5, SD = .08), F(1, 149) = 6.52, p = .012. ηp2 = .04. A significant Mole Type × Age interaction, F(1, 149) = 7.84, p = .006, ηp2 = .05, indicated that younger (M = 5.3, SD = .06) and older (M = 5.4, SD = .06) adults did not differ in their concerns about melanoma moles, t(153) = 1.35, p = .18, but older adults (M = 4.3, SD = .11) were more concerned about normal moles than were younger adults (M = 3.8, SD = .11), t(153) = 2.87, p = .005. Thus, younger adults were better able to distinguish harmful moles from normal moles, showing high concerns for only melanoma moles, whereas older adults showed higher concern for moles, regardless of type. There were no effects or interactions with instruction group, all ps > .49.

Website browsing behavior and time

Total time spent on skin-cancer related sites as opposed to unrelated sites was analyzed using a 2 (web type: skin-cancer related, unrelated) × 2 (age group: younger, older) × 3 (instruction group: control, emotion-focused, information-focused) mixed ANOVA. Participants spent more time browsing skin-cancer related sites (M = 167.25 s, SD = 9.07) than unrelated sites (M = 119.59 s, SD = 8.10), F(1, 75) = 8.50, p = .005, ηp2 = .10. There were no age, p = .78, instruction group, p = .30, or Age × Instruction Group differences, p = .65.

Give-away items

A 2 (age group: younger, older) × 3 (instruction group: control, emotion-focused, information-focused) ANOVA on the total number of give-away items chosen revealed that older adults, on average, chose 1 more item (M = 3) than did younger adults (M = 2), F(1, 148) = 16.31, p < .001, and older adults (n = 47) were more likely to choose a sunscreen with high SPF (30 or 50) than were younger adults (n = 36), χ2 (1, N = 154) = 3.81, p = .05. Those assigned to the information-focused instruction group were most likely to choose a sunscreen with higher SPF (n = 36) than those in other instruction groups (ncontrol = 21, and nemotion = 26), χ2 (1, N = 154) = 8.81, p = .01.

A 6 (item choice: selection of a mirror, magnet, pamphlet, extra body map, checklist, sunscreen) × 2 (age) × 3 (instruction group) mixed ANCOVA using gender as a covariate tested whether the higher proportion of women to men in the older adult group compared with the younger adult group may have influenced the age difference found in the selection of give-aways, as some studies have found gender differences in using sunscreen (e.g., Branstrom et al., 2004; Geller et al., 2002). Gender was not significant as a covariate and did not show any other effects, ps > .20; the effect of age was significant, F(1, 146) = 8.95, p = .003; older adults were more likely to select more items than were younger adults.

Likelihood of returning skin self-exam materials

Older adults were more likely to return the follow up (50 out of 77 returned, 64.9%) than were younger adults (38 out of 78 returned, 48.7%), χ2 (1, N = 155) = 4.15, p = .04. Instruction Group did not influence the likelihood of returning the follow up, χ2 (2, N = 155) = 1.26, p = .53, and there was not a significant age × instruction group interaction, χ2 (5, N = 155) = 8.35, p = .14.

Executive function and health behaviors

Correlations between executive functioning (ANT conflict scores) and behavioral measures were conducted for each age group to assess if behaviors might be compensating for poor cognitive abilities. Significant relationships were found only for younger adults: those with slower RTs to the conflict trials (indicating worse executive functioning) were also less likely to choose a mirror, r(76) = -.32, p = .005, and spent less time on the skin-cancer related sites, r(65) = -.27, p = .033.

Change in Knowledge of Skin Cancer

A 2 (test time: pre, post) × 2 (age group: younger, older) × 3 (instruction group: control, emotion-focused, information-focused) mixed ANOVA on the knowledge test scores examined whether older and younger adults differed in learning skin cancer information from the materials presented within the experiment. Generally, there were higher scores at post (M = 17.2, SD = .16) than at pre (M = 11.3, SD = .28), F(1, 146) = 526.09, p < .001, ηp2 = .78. A significant Time × Age interaction, F(1, 146) = 24.49, p < .001, ηp2 = .14, indicated that older adults knew more before the experiment (M = 12.1, SD = .39) than did younger adults (M = 10.5, SD = .39), t(150) = 2.97, p = .004, but older adults learned less after the experiment (M = 16.7, SD = .23) than did younger adults (M = 17.6, SD = .23), t(150) = 2.85, p = .005. There were no other effects or interactions, all ps > .23.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated to what extent age-related fixation patterns away from negative stimuli, which seem to help older adults successfully regulate their moods, might interfere with their ability to engage in positive health behavior suggested by negative but health-relevant communications. Younger and older adults viewed videos about skin cancer as their eyes were tracked. We assessed mood changes in response to the videos, as well as learning and behavior following recommendations in the videos.

No Mood-Health Behavior Trade-off With Age

We expected that older adults’ positive looking patterns toward the skin cancer videos might lead them to optimize their mood at the expense of internalizing positive health behavior. Indeed, we found that older adults tended to look less at the negative parts of the messages and felt better, on average, after the videos than did younger adults: older adults’ subjective mood ratings suggested that they more rapidly regulated their negative mood response to the videos than did younger adults. Contrary to our expectations, older adults engaged in equal or more health behavior (by most measures) than their younger counterparts. Older adults may have avoided looking at the negative components of the videos, but still engaged visually with the informational components. This pattern was especially characteristic of older adults in the emotion regulation condition, more so than in the other conditions. However, while fixation patterns varied by fixation type and instruction condition in both age groups, neither the affective nor the behavioral outcome measures varied by condition. That overall pattern suggests that condition-based modulation of older adults’ fixation to informational stimuli did not differentially impact mood or health behavior.

One possible explanation for this pattern of findings is that older adults are demonstrating an efficient looking strategy that allows them to extract important information from the videos without engaging visually with negatively-valenced material that might disrupt their mood. Younger adults may be constrained in their health behavior because they are distracted by the video-related disruption in their mood. Consistent with recent evidence that certain emotion regulation strategies may be less resource-demanding for older adults than for younger adults (Scheibe & Blanchard-Fields, 2009), older adults may be at a relative advantage in behavioral tasks because they are not occupied with regulating out of a lingering negative emotional state.

Of course, there are other possible explanations for the age difference, and future studies will need to disentangle these more specifically. For example, it will be important to demonstrate that the observed age differences in behavior result from actual interest in improving skin cancer-relevant behavior rather than other possible sources, such as compensatory processes to improve memory or an assenting response bias. Interestingly, these health behaviors did not correlate with executive functioning in the older adult sample.

It is nonetheless plausible that older adults took more of the giveaway items as cues to help them to remember to complete and return the skin self-exam, thus reflecting compensation rather than increased interest in the items per se. Older adults’ greater return of the self-exams may also have resulted from having fewer demands on their time and fewer other deadlines to hold in mind, especially compared to young adults attending college. However, instructing subjects to remember to complete a skin self-exam after leaving the lab and to return the completed exam form by mail is a classic prospective memory task: prospective memory involves memory for behaviors to be completed in the future. While studies point to conditions that might reduce age differences in prospective memory (such as habitual and focally cued tasks, e.g. Rose, Rendell, McDaniel, Aberle, & Kligel, 2010), recent evidence suggests that the overall age effect on prospective memory is robust, and shows a similar linear function from younger to older adulthood as does working memory (Maylor & Logie, 2010). Thus, for older adults to perform better than younger adults on a prospective memory task, especially one without formal cues (e.g., after leaving the lab, there was no telephone reminder to complete the self-exam and send it back), is especially impressive, and suggests that they were motivated by the material to encode the task in memory and complete the prospective task when it was appropriate to do so.

At the same time, older adults knew more about skin cancer before the videos, but learned less from the videos than did younger adults. This was also reflected in older adults’ higher ratings of concern for all moles — a hypervigilant response — whereas younger adults seemed better able to distinguish melanoma from normal moles. It is hard to know to what extent the age difference in learning can truly be attributed to learning less from the videos (which would be consistent with fixation data, but not the behavioral data) or less potential to learn given better previous knowledge. Older adults’ hypervigilant ratings of the mole images may have been a compensatory response to not having learned as much from the videos about what to look for in evaluating moles. Learning information about skin cancer and applying it to mole images were therefore the outcome measures that showed age-related deficits, providing a constraint on the possibly efficient looking pattern shown by older adults. Older adults’ positive looking strategy may enable them to balance mood regulation with the need to acquire certain health behaviors, but at the expense of encoding nuanced information that would require more engagement with negative stimuli. It remains to be investigated to what degree this might render older adults’ acquisition of positive health behaviors ultimately less useful.

Limitations

Several limitations of the current study deserve note. First, our health behavior measures were exploratory in nature and stopped far short of assessing actual sun exposure and/or ongoing skin self-exam. Future studies could expand the behavioral outcomes by including daily diary assessments of sun exposure and sunscreen use, for example. Second, we did not replicate past findings of within-age gender differences in sun exposure and/or sunscreen use; this may have been due to the fact that we collected all data in non-summer months in New England. Our New England sample may also be different in their sun-related behavior than samples from other studies, which tended to be in sunnier, warmer regions (e.g., Hawaii - Glanz et al., 2003; Australia - Aitken et al., 2004). We also did not find any effect of personal relevance of skin cancer on our findings; this may be due to our use of a low-risk sample, as compared to past studies that may have used high-risk samples and/or participants with family or personal history melanoma (e.g., Glanz et al., 2010). However, communication about skin cancer to improve health behavior is relevant to perceivers across the risk spectrum.

Conclusions: Pathways to Health Behavior

Older adults appeared to engage in relatively high levels of positive skin-cancer related behaviors. In some cases (e.g., browsing skin-cancer related websites), there were no age differences in those behaviors. In other cases, younger adults engaged in fewer health behaviors than did the older adults. For example, younger adults were less likely to take the high SPF sunscreen as recommended by the videos, even though fixation data suggested that younger adults were looking at skin cancer information and emotional content equally to, or perhaps more than, their older counterparts. Why might younger adults be “getting the message” visually, but not turning that attention into action? One possibility is that younger adults’ relatively greater fixation toward the negatively-valenced aspects of the videos may have distracted them from remembering, or desiring, to act in accordance with what they learned in the videos. Some evidence suggests that attention-grabbing public service messages reduce processing of the message content (e.g., Langleben et al., 2009), so the negatively-valenced material (that young adults looked at) may have grabbed their attention, but scared them, and thus lessened the persuasiveness of the health messages. Another possibility is that older adults, but not younger adults, used committing to engage in better health behavior as a mood regulatory tool in itself.

Either way, the pattern of results suggests that embedding health information in negatively-valenced material does not impair older adults’ ability to regulate their mood or to engage in the suggested health behaviors; the negative material may have actually enhanced health behavior by providing a focus for older adults trying to distract from the negative aspects of the videos. In contrast, younger adults seem impaired in their ability to regulate their mood and to engage in positive health behavior. This overall pattern is consistent with other findings suggesting that there may be different pathways to adaptive health communication for older and younger adults (e.g., Mikels et al., 2010). Thus, documentaries in which health information is given within upsetting stories about negative health outcomes seems to be an effective health promotion tool for older adults, but counterproductive for younger adults — for them, presenting “just the facts” might lead to better health behaviors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/HEA

References

- Aitken JF, Janda M, Lowe JB, Elwood M, Ring IT, Youl PH, Firman DW. Prevalence of whole-body skin self-examination in a population at high risk for skin cancer (Australia). Cancer Causes and Control. 2004;15:453–463. doi: 10.1023/B:CACO.0000036451.39128.f6. doi:10.1023/B:CACO.0000036451.39128.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, Ruhl J, Howlader N, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner MP, Lewis DR, Cronin K, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Stinchcomb DG, Edwards BK, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2010. pp. 1975–2007. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2007/, based on November 2009 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site. [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society Why you should know about melanoma. 2005 [Brochure]. Retrieved from http://www.cancer.org/

- American Academy of Dermatology Body Mole Map. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.aad.org/public/documents/Body_Mole_Map_11-09.pdf.

- Applied Science Labs EYE-TRAC 6 Desktop Video Head Tracking eye-tracker with facial recognition software [Apparatus and software] Bedford, MA: [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL. The influence of a sense of time on human development. Science. 2006;312:1913–1915. doi: 10.1126/science.1127488. doi:10.1126/science.1127488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Mikels J. At the intersection of emotion and cognition: Aging and the positivity effect. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:117–121. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00348.x. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Turan B, Scheibe S, Ram N, Ersner-Hershfield H, Samanez-Larkin GR, Brooks KP, Nesselroade JR. Emotional experience improves with age: Evidence based on over 10 years of experience sampling. Psychology and Aging. 2011;26:21–33. doi: 10.1037/a0021285. doi: 10.1037/a0021285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr., McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, Fl: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop S, Wakefield M, Kashima Y. Pathways to persuasion: Cognitive and experiential responses to health-promoting mass media messages. Communication Research. 2010;37:133–164. doi: 10.117/0093650209351912. [Google Scholar]

- GazeTracker (Version 8.0.3573.1000 FULL for ASL) [Computer software] EyeTellect, LLC; Charlottesville, VA: [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Mayer J. Reducing ultraviolet radiation exposure to prevent skin cancer. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;29:131–142. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.04.007. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Schoenfeld ER, Steffen A. A randomized trial of tailored skin cancer prevention messages for adults: Project SCAPE. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(4):735–741. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.155705. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2008.155705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Schoenfeld E, Weinstock MA, Layi G, Kidd J, Shigaki DM. Development and reliability of a brief skin cancer risk assessment tool. Cancer Detection and Prevention. 2003;27:311–315. doi: 10.1016/s0361-090x(03)00094-1. doi:10.1016/S0361-090X(03)00094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM. The gaze of the optimist. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;3:407–415. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271599. doi:10.1177/0146167204271599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM, Choi Y. The malleability of age-related positivity gaze preferences. Emotion. 2011;11:90–100. doi: 10.1037/a0021551. doi: 10.1037/a0021551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM, Toner K, Goren D, Wilson H. Looking while unhappy: Mood-congruent gaze in young adults, positive gaze in older adults. Psychological Science. 2008;19:848–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02167.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02167.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM, Toner K, Neupert SD. Use of gaze for real-time mood regulation: Effects of age and attentional functioning. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24:989–994. doi: 10.1037/a0017706. doi:10.1037/a0017706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM, Wadlinger HA, Goren D, Wilson HR. Is there an age-related positivity effect in visual attention? A comparison of two methodologies. Emotion. 2006a;6:511–516. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.6.3.511. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.6.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM, Wadlinger HA, Goren D, Wilson HR. Selective preference in visual fixation away from negative images in old age? An eye tracking study. Psychology and Aging. 2006b;21:40–48. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.40. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.21.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasparian NA, McLoone JK, Meiser B. Skin cancer-related prevention and screening behaviors: a review of the literature. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32:406–428. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9219-2. doi:10.1007/s10865-009-9219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzmann U, Richter D. Emotional reactivity across the adult life span: The cognitive pragmatics make a difference. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24:879–889. doi: 10.1037/a0017347. doi:10.1037/a0017347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langleben DD, Loughead JW, Ruparel K, Hakun JG, Busch-Winokur S, Holloway MB, Strasser AA, Cappella JN, Lerman C. Reduced prefrontal and temporal processing and recall of high “sensation value” ads. NeuroImage. 2009;46:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.12.062. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.12.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löckenhoff CE, Carstensen LL. Aging, emotion, and health-related decision strategies: Motivational manipulations can reduce age differences. Psychology and Aging. 2007;22:134–146. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.1.134. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.22.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Isaacowitz DM. How optimists face skin cancer information: Risk assessment, attention, memory, and behavior. Psychology and Health. 2007;22:963–984. doi:10.1080/14768320601070951. [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Carstensen LL. Aging and attentional biases for emotional faces. Psychological Science. 2003;14:409–415. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.01455. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.01455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maylor EA, Logie RH. Rapid communications: A large-scale comparison of prospective and retrospective memory development from childhood to middle age. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2010;63:442–451. doi: 10.1080/17470210903469872. doi:10.1080/17470210903469872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikels JA, Löckenhoff CE, Maglio SJ, Carstensen LL, Goldstein MK, Garber A. Following your heart or your head: Focusing on emotions versus information differentially influences the decisions of younger and older adults. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. 2010;16:87–95. doi: 10.1037/a0018500. doi: 10.1037/a0018500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh SR, Lohani M, Isaacowitz DM. Deliberate real-time mood regulation in adulthood: The importance of age, fixation and attentional functioning. Cognition and Emotion. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2010.541668. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelli DG, Robson JG, Wilkins AJ. The design of a new letter chart for measuring contrast sensitivity. Clinical Vision Science. 1988;2:187–199. [Google Scholar]

- Riediger M, Schmiedek F, Wagner GG, Lindenberger U. Seeking pleasure and seeking pain: Differences in prohedonic and contra-hedonic motivation from adolescence to old age. Psychological Science. 2009;20:1529–1535. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02473.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose NS, Rendell PG, McDaniel MA, Aberle I, Kligel M. Age and individual differences in prospective memory during a ‘Virtual Week’: The roles of working memory, vigilance, task regularity, and cue focality. Psychology and Aging. 2010;25:595–605. doi: 10.1037/a0019771. doi: 10.1037/a0019771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum JG. The biggest reward for my invention isn't money. Medical Economics. 1984;61:152–163. [Google Scholar]

- Scheibe S, Blanchard-Fields F. Effects of regulating emotions on cognitive performance: What is costly for young adults is not so costly for older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24:217–223. doi: 10.1037/a0013807. doi: 10.1037/a0013807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamaskin AM, Mikels JA, Reed AE. Getting the message across: Age differences in the positive and negative framing of health care messages. Psychology and Aging. 2010;25:746–751. doi: 10.1037/a0018431. doi: 10.1037/a0018431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiota MN, Levenson RW. Effects of aging on experimentally instructed detached reappraisal, positive reappraisal, and emotional behavior suppression. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24:890–900. doi: 10.1037/a0017896. doi:10.1037/a0017896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speelman C, Martin K, Flower S, Simpson T. Skill acquisition in skin cancer detection. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 2010;110:277–297. doi: 10.2466/PMS.110.1.277-297. doi:10.2466/pms.110.1.277-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Brown T. Sunburnt country. In: Thomson H, editor. Sixty Minutes Australia. Ninemsn Broadcasting; Australia: 2005. (Producer) (Reporter) February. [Television current affairs series episode] (Executive Producer) Available from http://sixtyminutes.ninemsn.com.au/stories/tarabrown/259248/sunburnt-country. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock MA, Risica PM, Martin RA, Rakowski W, Dubé C, Berwick M, Goldstein MG, Acharyya S, Lasater T. Melanoma early detection with thorough skin self-examination: The “check-it-out” randomized trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32:517–524. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.024. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock MA, Risica PM, Martin RA, Rakowski W, Smith KJ, Berwick M, Goldstein MG, Upegui D, Lasater T. Reliability of assessment and circumstances of performance of thorough skin self-examination for the early detection of melanoma in the Check-it-out Project. Preventive Medicine. 2004;38:761–765. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.01.020. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]