Abstract

Objectives

To describe the psychological needs of adolescent survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) or brain tumor (BT), we examined: (a) the occurrence of cognitive, behavioral, and emotional concerns identified during a comprehensive psychological evaluation, and (b) the frequency of referrals for psychological follow-up services to address identified concerns.

Methods

Psychological concerns were identified on measures according to predetermined criteria for 100 adolescent survivors. Referrals for psychological follow-up services were made for concerns previously unidentified in formal assessment or not adequately addressed by current services.

Results

Most survivors (82%) exhibited at least one concern across domains: behavioral (76%), cognitive (47%), and emotional (19%). Behavioral concerns emerged most often on scales associated with executive dysfunction, inattention, learning, and peer difficulties. CRT was associated with cognitive concerns, χ2(1,N=100)=5.63, p<0.05. Lower income was associated with more cognitive concerns for ALL survivors, t(47)=3.28, p<0.01, and more behavioral concerns for BT survivors, t(48)=2.93, p<0.01. Of survivors with concerns, 38% were referred for psychological follow-up services. Lower-income ALL survivors received more referrals for follow-up, χ2(1,N=41)=8.05, p<0.01. Referred survivors had more concerns across domains than non-referred survivors, ALL: t(39)=2.96, p<0.01, BT: t(39)=3.52, p<0.01. Trends suggest ALL survivors may be at risk for experiencing unaddressed cognitive needs.

Conclusions

Many adolescent survivors of cancer experience psychological difficulties that are not adequately managed by current services, underscoring the need for long-term surveillance. In addition to prescribing regular psychological evaluations, clinicians should closely monitor whether current support services appropriately meet survivors’ needs, particularly for lower-income survivors and those treated with CRT.

Keywords: cancer, oncology, psychological, children

INTRODUCTION

With improved survival rates for pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and brain tumors (BT) over the past several decades [1], there is an increasing urgency to understand the post-treatment psychological needs of this growing population of pediatric cancer survivors. Survivors of ALL and BT are at risk for psychological difficulties (cognitive, behavioral, and emotional) attributable to disease and certain treatments, including intrathecal chemotherapy, cranial radiation therapy (CRT), and neurosurgery [2–7]. Neurocognitive late effects are widely documented following treatment for pediatric ALL and BT [6,8–14]. The impact of disease and treatment on the emotional and behavioral functioning of survivors is less clear. Reviews find that most studies report favorable psychosocial outcomes for survivors in comparison to siblings, healthy controls, and normative samples [15–18]. Still, a critical subset remains at risk for psychosocial dysfunction. BT diagnosis and central nervous system (CNS)-directed therapies are consistently identified risk factors for post-treatment emotional and behavioral difficulties [15,17–19]. Time since treatment, age at diagnosis, and gender also are important correlates of psychosocial outcomes [17,19,20].

Many studies have examined psychosocial outcomes in adult survivors of pediatric cancer [21–24], yet it is important to recognize that survivorship begins in childhood and adolescence for many pediatric cancer survivors. Other studies report outcomes for small samples of child and adolescent survivors across broad age ranges [25–27]. These studies may lack the sensitivity to detect age differences in functioning attributable to the maturational, social, cognitive, and educational transitions that make adolescents especially vulnerable to psychosocial hardships [28]. Recent studies of adolescent survivors suggest this age group may be particularly at risk. Compared to siblings, adolescent survivors were more likely to have depressive and anxious symptoms, peer difficulties [29], attention deficits, and general emotional problems [30] based on parent reports. Adolescent survivors were also found to report worse social functioning and more anxiety than healthy controls [31].

Adolescent survivors have been under-studied, and it is unclear whether the psychosocial needs of these survivors are adequately met [32,33]. The Children’s Oncology Group (COG) issued guidelines for the long-term psychological follow-up care of pediatric cancer survivors [34]. Recommendations include annual psychosocial monitoring for all survivors as well as baseline neuropsychological evaluations for those at high risk for cognitive sequelae with periodic reevaluation as clinically indicated. Such guidelines are not easily enacted, particularly due to resource limitations. Even when health care providers and families are perceptive and proactive, logistical barriers may impede the delivery of necessary school or psychological services in many settings.

Accordingly, this study explored whether the psychological needs of adolescent survivors are identified and adequately treated through routine clinical care. Within a broad sampling of adolescent ALL and BT survivors, we examined the occurrence of cognitive, behavioral, and emotional concerns identified during a comprehensive psychological evaluation. We also examined the frequency with which referrals were made for psychological follow-up services to address the concerns identified in the evaluation. Based on the psychological risk associated with BTs and their treatment, we expected to find a higher occurrence of concerns and referrals among BT survivors compared to ALL survivors. We also expected that most concerns would be identified on performance-based measures of cognitive functioning compared to measures of behavioral or emotional functioning for the BT survivors.

METHODS

Patients

Data were examined for adolescent survivors originally enrolled on a research protocol investigating cognitive functioning and health behaviors [35]. The original protocol enrolled English-speaking patients who were age 12–17 years, diagnosed with ALL or BT, ≥1 year since completion of treatment, and with no evidence of active disease. Patients with significant intellectual impairment (i.e., IQ <70 documented in the medical record) were excluded from the study to ensure participants were able to complete all study measures.

The total sample included 100 survivors (50 ALL, 50 BT). Demographic and clinical characteristics for ALL and BT participants are reported in Tables I and II, respectively. Statistically significant demographic and clinical differences were identified between diagnostic groups. More participants in the BT group received CRT than in the ALL group, χ2(1,N=100)=43.71, p<0.001. All participants in the ALL group received chemotherapy compared to only 52.0% of BT participants, χ2(1,N=100)=31.58, p<0.001. Survivors of ALL were younger at diagnosis, t(98)=4.69, p<0.001, and had been off treatment longer at study enrollment, t(98)=2.05, p<0.05, compared to BT survivors in this sample. The ALL group had more participants in the lower-income category (annual household income <$40,000) than the BT group, χ2(1,N=99)=11.82, p<0.001. In most analyses reported, data are examined separately for these diagnostic groups.

Table I.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics and Univariate Comparisons of ALL Survivors by Clinical Concern and Referral Status

| Characteristic | ALL Survivors

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Participants

|

With Clinical Concerns

|

Referred for Follow-up

|

||||||

| N | % | n | Row % | p | n | Row %a | p | |

| Total | 50 | 100.0 | 41 | 82.0 | – | 17 | 41.5 | – |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 25 | 50.0 | 21 | 84.0 | 1.000 | 6 | 28.6 | 0.086 |

| Male | 25 | 50.0 | 20 | 80.0 | 11 | 55.0 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 43 | 86.0 | 35 | 81.4 | 1.000 | 13 | 37.1 | 0.212 |

| Non-White | 7 | 14.0 | 6 | 85.7 | 4 | 66.7 | ||

| Parental annual incomeb | ||||||||

| < $40,000 | 18 | 36.0 | 16 | 88.9 | 0.693 | 11 | 68.8 | 0.005** |

| ≥ $40,000 | 31 | 62.0 | 25 | 80.6 | 6 | 24.0 | ||

| Cranial radiation therapy | ||||||||

| No | 43 | 86.0 | 34 | 79.1 | 0.325 | 12 | 35.3 | 0.105 |

| Yes | 7 | 14.0 | 7 | 100.0 | 5 | 71.4 | ||

| Chemotherapy | ||||||||

| No | 0 | 0.0 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Yes | 50 | 100.0 | 41 | 82.0 | 17 | 41.5 | ||

|

|

|

|

||||||

| M ± SD | Range | M ± SD | Range | p | p | |||

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Age at study participation | 14.9 ± 2.0 | 12.2 – 18.0 | 14.9 ± 2.0 | 12.2 – 18.0 | 0.988 | 14.6 ± 2.1 | 12.2 – 18.0 | 0.356 |

| Age at diagnosis | 5.0 ± 3.1 | 0.7 – 13.0 | 4.8 ± 3.2 | 0.7 – 13.0 | 0.333 | 5.2 ± 3.1 | 1.9 – 13.0 | 0.443 |

| Years since treatment | 7.1 ± 3.3 | 1.5 – 15.5 | 7.2 ± 3.3 | 1.5 – 15.5 | 0.444 | 6.5 ± 2.9 | 1.5 – 10.8 | 0.229 |

Note.

Row % for “ALL Survivors Referred for Follow-up” uses the ns from “ALL Survivors With Clinical Concerns” as the denominator in each row.

Missing parental annual income data (n = 1). p-values are reported for comparisons of clinical concern status (With Clinical Concerns, No Clinical Concerns) and referral status (Referred, Not Referred) across demographic and clinical variables using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests for dichotomous and t-tests for continuous variables. Comparisons of referral status included only those survivors with one or more clinical concerns. Some survivors are represented in more than one treatment category. All survivors of ALL in this sample had received chemotherapy.

p<.05.

p<.01.

p<.001.

Table II.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics and Univariate Comparisons of BT Survivors by Clinical Concern and Referral Status

| Characteristic | BT Survivors

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Participants

|

With Clinical Concerns

|

Referred for Follow-up

|

||||||

| N | % | n | Row % | p | n | Row %a | p | |

| Total | 50 | 100.0 | 41 | 82.0 | – | 14 | 34.1 | – |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 25 | 50.0 | 19 | 76.0 | 0.464 | 6 | 31.6 | 0.747 |

| Male | 25 | 50.0 | 22 | 88.0 | 8 | 36.4 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 42 | 84.0 | 36 | 85.7 | 0.144 | 11 | 30.6 | 0.317 |

| Non-White | 8 | 16.0 | 5 | 62.5 | 3 | 60.0 | ||

| Parental annual income | ||||||||

| < $40,000 | 4 | 8.0 | 4 | 100.0 | 1.000 | 3 | 75.0 | 0.107 |

| ≥ $40,000 | 46 | 92.0 | 37 | 80.4 | 11 | 29.7 | ||

| Cranial radiation therapy | ||||||||

| No | 10 | 20.0 | 9 | 90.0 | 0.665 | 2 | 22.2 | 0.693 |

| Yes | 40 | 80.0 | 32 | 80.0 | 12 | 37.5 | ||

| Chemotherapy | ||||||||

| No | 24 | 48.0 | 21 | 87.5 | 0.467 | 7 | 33.3 | 0.910 |

| Yes | 26 | 52.0 | 20 | 76.9 | 7 | 35.0 | ||

|

|

|

|

||||||

| M ± SD | Range | M ± SD | Range | p | M ± SD | Range | p | |

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Age at study participation | 15.0 ± 1.8 | 12.1 – 18.0 | 15.1 ± 1.7 | 12.2 – 17.9 | 0.393 | 15.2 ± 1.1 | 13.4 – 17.0 | 0.778 |

| Age at diagnosis | 8.2 ± 3.7 | 2.0 – 15.2 | 8.1 ± 3.9 | 2.0 – 15.2 | 0.927 | 8.3 ± 3.7 | 2.1 – 13.4 | 0.811 |

| Years since treatment | 5.6 ± 3.7 | 1.1 – 16.0 | 5.6 ± 3.5 | 1.1 – 13.0 | 0.987 | 5.4 ± 3.5 | 1.2 – 11.4 | 0.796 |

Note.

Row % for “BT Survivors Referred for Follow-up” uses the ns from “BT Survivors With Clinical Concerns” as the denominator in each row. p-values are reported for comparisons of clinical concern status (With Clinical Concerns, No Clinical Concerns) and referral status (Referred, Not Referred) across demographic and clinical variables using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests for dichotomous and t-tests for continuous variables. Comparisons of referral status included only those survivors with one or more clinical concerns. Some survivors are represented in more than one treatment category.

Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at the pediatric cancer hospital where the study was conducted. Patients were identified on consecutive clinic schedules, and research visits were scheduled in coordination with medical follow-up visits. Only 14 eligible patients and families declined to participate. Most (n=9) reported the time required to participate was the primary reason they declined. Other reasons for declining included: concern that the evaluation asked uncomfortable questions (n=2), dissatisfaction with a past psychological evaluation (n=1), and concern about a recent family death (n=1). One family chose not to disclose a reason for declining. In addition to the high participation rate (87.7%), no differences by age, gender, diagnostic group, or age at diagnosis were found between those who participated and declined, supporting the representativeness of this sample.

Measures

Conners 3rd Edition (Conners 3)

The self-, parent-, and teacher-report versions of the Conners 3 [36] were administered, assessing symptoms associated with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and other attention-related disorders. Adequate internal consistency has been established across scales for all three versions: self-report r=0.81–0.92, parent-report r=0.83–0.94, and teacher-report r=0.77–0.97 [36]. T-scores are derived from age norms (M=50, SD=10).

Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF)

The BRIEF [37] is a parent-report questionnaire assessing behaviors associated with executive functioning in daily activities. Reports of internal consistency reliability range from 0.80–0.98 across indexes, and mean test-retest reliabilities across clinical scales are good for parents (r=0.81) and teachers (r=0.87) [37]. T-scores are derived from age norms (M=50, SD=10).

Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents-IV (DICA-IV), Parent Version

The DICA-IV [38] is a comprehensive structured interview assessing mental health disorders in children and adolescents based on the diagnostic criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) [39]. The computerized DICA-IV modules were administered to parents by a psychologist and assessed the patient’s history and current presentation of behavioral disorders (ADHD, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, Conduct Disorder), anxiety disorders (Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Social Anxiety Disorder, Specific Phobia, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Panic Disorder), and mood disorders (Major Depressive Episode, Mania, Dysthymia). The DICA has demonstrated strong inter-rater reliability across studies [40] and solid test-retest reliability and cross-informant agreement in a clinical sample [41].

Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI)

An estimate of general intellectual functioning was derived from the Vocabulary and Matrix Reasoning subtests of the WASI [42]. The WASI estimated IQ score is highly correlated with the comprehensive full scale IQ scores of the Wechsler intelligence scales (Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition (WISC-IV) r=0.82; Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Third Edition (WAIS-III) r=0.87) [43,44]. The WASI estimated IQ was converted to a standard score (M=100, SD=15) computed from age norms.

Wechsler Processing Speed Index

The Processing Speed Index measures the speed and accuracy of processing and sequencing simple visual information. The two subtests comprising the index (Coding and Symbol Search) were administered from the age-appropriate Wechsler scale for each participant (WISC-IV [45] for ages ≤ 16 years; WAIS-III [46] for ages ≥ 17 years). The test-retest stability coefficient for the Processing Speed Index is 0.86 on the WISC-IV and 0.84 on the WAIS-III, indicating good reliability on both measures [43,47]. Standard scores are derived from age norms (M=100, SD=15).

Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS), Color-Word Interference Test

The D-KEFS Color-Word Interference Test [48] provides a measure of executive function involving verbal inhibition and cognitive flexibility. This task consists of four conditions: Color Naming (naming colors in a series), Word Reading (reading printed color names), Inhibition (naming the ink color of color names printed in dissonant ink), and Inhibition/Switching (switching between reading a color name or naming the ink color according to a rule). The Color-Word Interference Test has demonstrated discriminative validity for detecting executive dysfunction in pediatric samples versus matched controls [49,50]. Scaled scores are derived from age norms (M=10, SD=3).

Conners’ Continuous Performance Test-II (CPT-II)

The CPT-II [51] is a computerized, performance-based measure of attention. This task requires the participant to watch a random series of letters presented one at a time on the computer screen. The participant is instructed to press the space bar each time a letter appears on screen, except for the letter ‘X.’ Internal consistency ranges from limited to excellent across indexes (r=0.66–0.95) [51]. T-scores are derived from age norms (M=50, SD=10).

Study measures were categorized by the primary clinical domain (cognitive, behavioral, or emotional) assessed (Table III). The cognitive domain includes only performance-based measures of cognitive abilities (estimated IQ, Processing Speed Index, Color-Word Interference Test, and CPT-II). The behavioral and emotional domains include informant-report measures only (i.e., behavior rating scales and/or parent-reported symptoms on the DICA-IV). Specifically, the behavioral domain includes the Conners 3 (all informants), the BRIEF, and the DICA-IV Behavioral Disorders modules. The emotional domain includes the DICA-IV Emotional Disorders modules (anxiety and depressive disorders). Some measures in the cognitive and behavioral domains overlap in their assessment of similar underlying cognitive constructs (e.g., attention, executive function). Since studies have found poor correlations between performance-based and informant-report assessments of cognitive functions [52–55], we categorized overlapping measures into cognitive and behavioral domains based on measurement approach. Categorizing measures into these three domains is intended to provide a broad framework for understanding those components of the assessment that yielded the highest number of clinical concerns and that were associated with the highest number of clinical referrals.

Table III.

Number of Survivors with Clinical Concerns Identified on Psychological Outcome Measures and Percentage of Survivors Referred by Diagnostic Group

| Domain and Measures | ALL Survivors with Clinical Concerns (n= 41)

|

BT Survivors with Clinical Concerns (n = 41)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % Referred | p | n | % Referred | p | |

|

|

|

|||||

| Behavioral | 39 | 41.0 | 1.000 | 37 | 37.8 | 0.280 |

| Conners 3 (parent-report) | 27 | 48.1 | 0.177 | 30 | 40.0 | 0.275 |

| Conners 3 (teacher-report)a | 12 | 75.0 | 0.017* | 16 | 50.0 | 0.273 |

| Conners 3 (self-report) | 21 | 47.6 | 0.412 | 20 | 45.0 | 0.176 |

| BRIEF | 23 | 47.8 | 0.350 | 24 | 50.0 | 0.018* |

| DICA-IV Behavioral Disorders | 5 | 60.0 | 0.633 | 4 | 50.0 | 0.596 |

| Cognitive | 21 | 61.9 | 0.011* | 26 | 42.3 | 0.186 |

| Estimated IQ | 0 | 0.0 | – | 3 | 0.0 | 0.539 |

| Processing Speed Indexa | 6 | 83.3 | 0.066 | 13 | 38.5 | 0.462 |

| Color-Word Interference Testa | 14 | 71.4 | 0.008** | 16 | 37.5 | 0.717 |

| CPT-IIa | 10 | 60.0 | 0.270 | 15 | 60.0 | 0.005** |

| Emotional | ||||||

| DICA-IV Emotional Disorders | 9 | 33.3 | 0.711 | 10 | 60.0 | 0.064 |

|

|

|

|||||

| Total # of Clinical Concerns | Not Referred | Referred | p | Not Referred | Referred | p |

|

|

|

|||||

| M ± SD (Range) | M ± SD (Range) | M ± SD (Range) | M ± SD (Range) | |||

|

|

|

|||||

| Behavioral | 3.9 ± 4.4 (0.0 – 17.0) | 10.5 ± 9.9 (0.0 35.0) | 0.014* | 5.1 ± 6.1 (0.0 – 23.0) | 11.7 ± 8.9 (2.0 – 28.0) | 0.018* |

| Cognitive | 0.5 ± 0.9 (0.0 – 3.0) | 2.2 ± 1.6 (0.0 – 5.0) | <0.001*** | 1.5 ± 1.8 (0.0 – 6.0) | 2.6 ± 2.6 (0.0 – 8.0) | 0.116 |

| Emotional | 0.4 ± 0.9 (0.0 – 4.0) | 0.4 ± 1.1 (0.0 – 4.0) | 0.988 | 0.3 ± 1.0 (0.0 – 5.0) | 0.6 ± 0.8 (0.0 – 2.0) | 0.370 |

| All Domains | 5.3 ± 6.0 (1.0 – 24.0) | 12.8 ± 10.1 (2.0 – 41.0) | 0.005** | 6.5 ± 7.1 (1.0 – 30.0) | 15.5 ± 9.0 (5.0 – 33.0) | 0.001** |

Note. n = number of survivors with a clinical concern identified in each domain (cognitive, behavioral, emotional) and on each measure. % Referred = % of survivors with clinical concerns on each domain/measure that were referred for psychological follow-up services.

Scores were missing for patients unable to complete the Processing Speed Index, Color-Word Interference Test, and CPT-II due to visual impairment (n = 2), for patients who fell asleep during administration of the Processing Speed Index and CPT-II (n = 2), for teacher-report forms not returned by teachers (n = 5), and teacher-report forms not included for parent-instructed homeschooled children (n = 6). p-values are reported for comparisons of referral status (Referred, Not Referred) by clinical concern status (Clinical Concern, No Clinical Concern) on each domain and measure using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests. T-tests compared mean differences in the total number of clinical concerns experienced by referral status. All comparisons included only those survivors with one or more clinical concerns.

p<.05.

p<.01.

p<.001.

Procedure

Following informed consent and assent procedures, participants underwent cognitive assessment and completed a behavior rating scale. The parent or guardian participated in a structured diagnostic interview and completed rating scales. The primary teacher of each participant also completed a rating scale reporting on the child’s classroom behavior.

Following evaluation, study measures were examined for clinical concerns in cognitive, behavioral, and/or emotional functioning. A clinical concern was identified according to the following criteria: (1) a score deviation on standardized measures (± 1.5 SD from the normative mean) in the direction of problematic functioning, AND/OR (2) the fulfillment of criteria for a clinical disorder on the DICA-IV. (The ± 1.5 SD from the mean criterion is often the lower end of the range customarily used to identify significant clinical concerns on most standardized measures)[56]. If an area of clinical concern was identified, a referral for psychological follow-up services was made according to the following criteria: (1) the clinical concern had not been previously identified in formal psychological assessment as documented in the medical record or psychology chart, AND/OR (2) the clinical concern was not adequately addressed by current school or psychological services based on the family’s report. Decisions for referral were agreed upon by both the examining psychologist (who performed all study evaluations) and the attending psychologist (one of five psychologists on weekly rotation as attending). Referrals for psychological follow-up included referral to any service provided in the hospital’s Psychology Clinic (consultation, assessment, and/or intervention). Referrals for rehabilitation services (e.g., physical therapy) are not examined.

Statistical Analysis

This study provides descriptive information about the number of clinical concerns identified in a comprehensive psychological evaluation, the number of referrals made for psychological follow-up services based on concerns identified during the evaluation, and the characteristics associated with clinical concerns and referrals. To examine relationships between groups on demographic, clinical, and psychological variables, we used χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests for dichotomous variables and t-tests for continuous variables. Pearson correlations were used to examine relationships between continuous variables. The significance level (p<0.05) was not adjusted for multiple comparisons because of the exploratory nature of this investigation.

RESULTS

Occurrence of Clinical Concerns

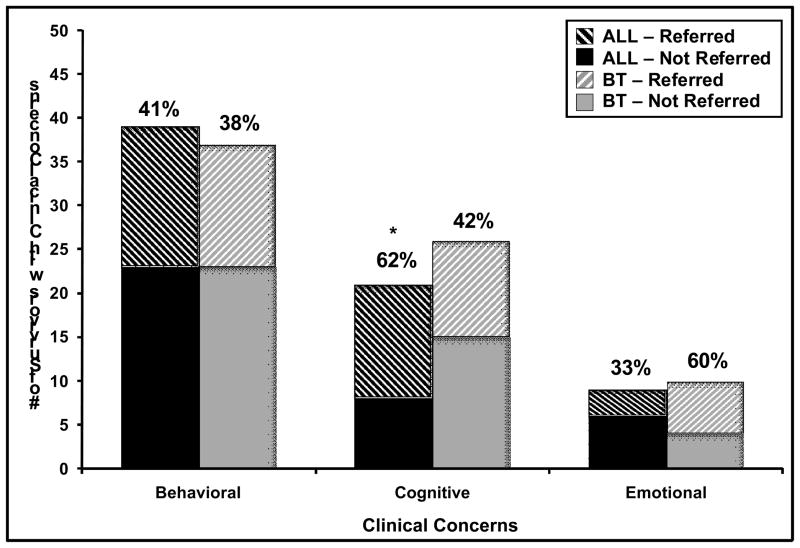

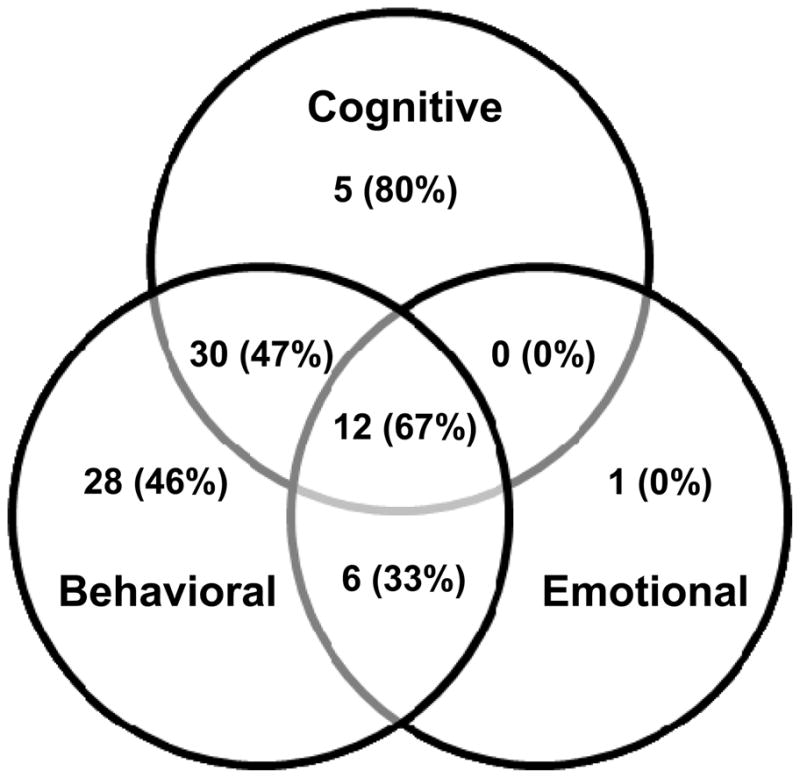

At least one clinical concern was identified across study measures for 82.0% of survivors (41 ALL, 41 BT). Of those survivors with any clinical concerns identified (n=82), most (58.5%) exhibited concerns in two or more domains of functioning. The greatest overlap occurred for survivors with concerns in both cognitive performance and behavioral domains (Figure 1). Patients with behavioral problems also had more cognitive problems, χ2(1,N=100)=8.68, p<0.01; having emotional problems was not associated with having cognitive or behavioral problems. Behavioral concerns were most frequent, experienced by 76.0% of survivors. Cognitive concerns were identified in 47.0% of survivors. Emotional concerns were least frequent, detected in 19.0% of the sample. The 12 survivors who exhibited clinical concerns in all three domains were 66.7% BT and 83.3% post-CRT. Figure 2 presents the frequency of clinical concerns by domain and diagnostic group.

Figure 1.

Number of survivors (% BT) with identified clinical concerns by domain (N = 82).

Figure 2.

Number of survivors with clinical concerns and % referred for follow-up by domain (Emotional, Behavioral, Cognitive) and diagnostic group (BT, ALL). Some survivors experienced clinical concerns in multiple domains and are represented in each respective category above. *Having a cognitive concern was associated with receiving a clinical referral among ALL survivors (p < 0.05, Fisher’s exact test). No statistically significant differences in frequency of referrals were found between diagnostic groups in any domain.

Correlates of Clinical Concerns

Fisher’s exact tests, χ2 tests, and t-tests identified demographic and clinical characteristics associated with the identification of clinical concerns on assessment (With Clinical Concerns versus No Clinical Concerns). The identification of clinical concerns did not differ between ALL and BT groups (data not shown); however, having a history of CRT was associated with experiencing cognitive problems in the combined sample, χ2(1,N=100)=5.63, p<0.05. No other demographic or clinical variables were found to be significantly associated with having any clinical concerns (versus none) among ALL or BT survivors (Tables I and II).

T-tests and Pearson correlations examined associations between the number of clinical concerns identified in and across domains and the demographic and clinical characteristics of survivors. In the ALL group, survivors with a history of CRT exhibited a higher number of cognitive (MCRT=2.6, MNo CRT=0.7, t(48)=3.52, p<0.01) and behavioral concerns (MCRT=12.1, MNo CRT=4.5, t(48)=2.70, p<0.01) as well as a higher total number of concerns across all domains (MCRT=15.7, MNo CRT=5.4, t(48)=3.23, p<0.01) than survivors without CRT. ALL survivors from lower-income families exhibited a higher number of cognitive concerns (M=1.9) than survivors from higher income families (M=0.5), t(47)=3.28, p<0.001. Older age at diagnosis was associated with having a higher number of emotional concerns among ALL survivors, r=0.31, p<0.05.

In the BT group, survivors treated with CRT exhibited more cognitive concerns (M=1.8) than survivors without a history of CRT (M=0.5), t(48)=2.84, p<0.01. BT survivors from lower-income families experienced more behavioral concerns (MLow=15.5, MHigh=5.1, t(48)=2.93, p<0.01) and a higher total number of concerns across all domains (MLow= 18.5, MHigh=6.9, t(48)=2.68, p<0.05) than survivors with higher family incomes. No statistically significant associations were found for either diagnostic group between the number of identified clinical concerns and gender, race, age, or time since completion of treatment.

Occurrence of Referrals for Clinical Follow-up

Of those survivors with identified clinical concerns (n=82), 37.8% received referrals for psychological follow-up services (i.e., for further psychological assessment, consultation, and/or intervention) based on findings from study measures. Similar numbers of ALL (n=17) and BT survivors (n=14) received referrals for follow-up. Figure 2 presents the number of survivors exhibiting clinical concerns by domain and the percentage of those survivors who received referrals for psychological follow-up.

Correlates of Referrals for Clinical Follow-up

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Fisher’s exact tests, χ2 tests, and t-tests identified demographic and clinical characteristics associated with receiving a referral for psychological follow-up services among survivors with any identified clinical concerns. Significance values are reported in Table I (ALL) and Table II (BT). Among ALL survivors, receiving a referral was associated with lower household income, χ2(1,N=41)=8.05, p<0.01. No other significant associations were found between referral status and demographic and clinical characteristics for either diagnostic group.

Psychological domains and measures

Most survivors that received referrals for psychological follow-up services (80.7%) exhibited clinical concerns in two or more domains. Table III reports the number of survivors with clinical concerns identified on specific psychological outcome measures and the percentage of those survivors referred for follow-up. Including only those survivors with one or more identified clinical concerns in analysis, Fisher’s exact tests and χ2 tests were used to identify if receiving a referral was associated with having clinical concerns identified on individual measures or in specific domains. T-tests examined associations between referral status (Referred, Not Referred) and the number of clinical concerns identified within and across clinical domains. Significance values are reported in Table III.

Many survivors exhibited clinical concerns in the behavioral domain, which is comprised of several informant-report rating scales and DICA-IV modules. The number of clinical concerns identified and the associated referral status across measures in the behavioral domain are reported in Table IV. In this domain, the most frequent concerns emerged on the parent-report BRIEF and Conners 3. The scale that resulted in the most elevations assessed working memory behaviors on the BRIEF. On the Conners 3, clinical scores on the Learning Problems, Inattention, and Peer Relations scales were most frequent across reporters. The fewest concerns were identified on the DICA-IV Behavioral Disorders modules. Survivors with parent-reported executive dysfunction (e.g., Conners 3 Executive Functioning scale, BRIEF Plan/Organize and Metacognition scales) were frequently referred. Although externalizing problems (e.g., hyperactivity/impulsivity, oppositional behavior, conduct problems, aggression) were relatively infrequent in this sample, when such elevations were identified, referrals were frequent, particularly when concerns emerged on the teacher-report form.

Table IV.

Number of Survivors with Clinical Concerns Identified on Behavioral Measures and Percentage of Survivors Referred

| Behavioral Measures and Scales | Survivors with Clinical Concerns on Behavioral Measures (n = 76)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % Referred | na | % Referred | n | % Referred | |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Parent-Report | Teacher-Report | Self-Report | ||||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Conners 3 | ||||||

| Inattention | 25 | 60.0 | 12 | 66.7 | 19 | 57.9 |

| Hyperactivity/Impulsivity | 16 | 50.0 | 6 | 83.3 | 11 | 27.3 |

| Learning Problems | 27 | 59.3 | 19 | 68.4 | 19 | 63.2 |

| Executive Functioning | 21 | 71.4 | 6 | 66.7 | — | — |

| Aggression | 12 | 50.0 | 4 | 75.0 | 11 | 63.6 |

| Peer Relations | 29 | 37.9 | 14 | 64.3 | — | — |

| Family Relations | — | — | — | — | 3 | 66.7 |

| Conduct Disorder | 9 | 66.7 | 2 | 100.0 | 10 | 70.0 |

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 13 | 69.2 | 7 | 57.1 | 7 | 71.4 |

| ADHD Index | 18 | 66.7 | 7 | 71.4 | 17 | 35.3 |

| Global Index | 18 | 50.0 | 10 | 50.0 | — | — |

| BRIEF | ||||||

| Inhibit | 12 | 66.7 | — | — | — | — |

| Shift | 20 | 60.0 | — | — | — | — |

| Emotional Control | 12 | 50.0 | — | — | — | — |

| Initiate | 19 | 63.2 | — | — | — | — |

| Working Memory | 30 | 56.7 | — | — | — | — |

| Plan/Organize | 19 | 78.9 | — | — | — | — |

| Organization of Materials | 18 | 50.0 | — | — | — | — |

| Monitor | 15 | 66.7 | — | — | — | — |

| Behavioral Regulation Index | 11 | 63.6 | — | — | — | — |

| Metacognition Index | 18 | 72.2 | — | — | — | — |

| Global Executive Composite | 16 | 68.8 | — | — | — | — |

| DICA-IV Behavioral Disorders | ||||||

| ADHD | 4 | 75.0 | — | — | — | — |

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 8 | 50.0 | — | — | — | — |

| Conduct Disorder | 1 | 0.0 | — | — | — | — |

Note. n = number of survivors with a clinical concern identified on each scale of the behavioral measures. % Referred = % of survivors with clinical concerns on each scale that were referred for psychological follow-up services.

Scores were missing for teacher-report forms not returned by teachers (n = 5) and teacher-report forms not included for parent-instructed homeschooled children (n = 6).

In the ALL group, survivors referred for psychological follow-up had a higher number of behavioral concerns, t(39)=2.57, p<0.05, cognitive concerns, t(39)=4.14, p<0.001, and total number of concerns across all domains, t(39)=2.96, p<0.01, compared to survivors who were not referred. The number of emotional concerns was not associated with referral status in this group. Most ALL survivors with concerns on the following measures were referred for psychological follow-up: Conners 3 teacher-report form, DICA-IV behavioral disorders modules, Processing Speed Index, Color-Word Interference Test, and CPT-II. Receiving a referral for psychological follow-up services was significantly associated with having a cognitive concern (p<0.05, Fisher’s exact test; Figure 2) and with having a concern identified on the Conners 3 teacher-report form (p<0.05, Fisher’s exact test) and the Color-Word Interference Test (p<0.01, Fisher’s exact test).

In the BT group, survivors who were referred for psychological follow-up also had a higher number of behavioral concerns, t(39)=3.56, p<0.01, and a higher total number of concerns across all domains, t(39)=3.52, p<0.01, compared to survivors who were not referred. The number of emotional or cognitive concerns was not associated with referral status in this group. Most BT survivors with concerns identified on the CPT-II and the DICA-IV emotional disorders modules were referred for psychological follow-up. Among BT survivors, receiving a referral was associated with the identification of a clinical concern on the BRIEF (p<0.05, Fisher’s exact test) and the CPT-II (p<0.01, Fisher’s exact test). No other associations with referral status were found for either diagnostic group.

History of Psychological Services for Survivors

Most survivors in this sample (92%) had undergone psychological testing (clinical or research) in the past. BT survivors had been tested more recently than ALL survivors (time since last testing: MBT=22.0 months, MALL=36.4 months), t(89)=2.51, p<0.05. Longer time since last testing was associated with longer time since diagnosis and time off treatment (r=0.54 and r=0.56, respectively, both p<0.001). Family income was not significantly associated with time since testing. Having past testing and time since testing were not statistically associated with receiving a clinical referral.

Most survivors in this sample (59%) received school services in the past (ranging from tutoring to special education). More BT survivors received school services than ALL survivors, χ2(1,N=100)=11.95, p<0.01. Among survivors with clinical concerns, currently receiving school services was associated with receiving a clinical referral, χ2(1,N=82)=4.20, p<0.05, but not income. Nearly one quarter of the sample (24%) had been retained for at least one grade in school, which was not associated with diagnostic group or referral. Finally, 28% of the sample had received past psychological intervention (counseling or therapy), with only 9% of survivors currently receiving these services. Having received psychological intervention services was not associated with diagnostic group, income, or referral in this sample.

CONCLUSIONS

The substantial majority (82.0%) of adolescent survivors of pediatric ALL and BT in this sample exhibited cognitive, behavioral, and/or emotional concerns identified on psychological assessment. Many of those survivors (37.8%) were referred for psychological follow-up services when these concerns had not been previously identified or were inadequately managed by current support services. These findings suggest many adolescent survivors experience clinically concerning psychological symptoms that remain unidentified or untreated.

Most survivors (76.0%) exhibited behavioral concerns, while cognitive and emotional concerns were less common (detected in 47.0% and 19.0% of survivors, respectively). Concerns were often identified in multiple domains of functioning, with particular overlap between behavioral and cognitive domains, consistent with the overlap in constructs assessed by some informant-report measures in the behavioral domain and performance-based measures in the cognitive domain. In fact, most behavioral concerns were identified on the Conners 3 and the BRIEF, rating scales assessing behaviors associated with attention and executive function. Within the behavioral domain, clinical concerns emerged most often on scales assessing behaviors associated with executive functioning, inattention, learning problems, and peer relations. Externalizing problems (e.g., hyperactivity/impulsivity, conduct problems, oppositionality) were infrequent. In those patients that did exhibit such problems, referrals for follow up services were common.

Emotional concerns were infrequent and rarely occurred in isolation. Most survivors with emotional concerns also exhibited behavioral and cognitive concerns, possibly representing a subset of the most severely impaired survivors in this sample. Nearly all survivors in this group had a history of CRT (83.3%) and most had a BT diagnosis (66.7%), two of the most consistent clinical risk factors for post-treatment psychological dysfunction [15,17–19].

A recent national survey of adolescents in the U.S. reported that one in every four to five adolescents meets criteria for a mental disorder, with 40% of those experiencing more than one disorder [57]. Clearly, adolescents in the general population are quite vulnerable to pathological trajectories, perhaps due, in part, to lagging frontal lobe development and/or hormonal surges during puberty that contribute to insufficient inhibitory responses of heightened emotionality [58,59]. Adolescence is also marked by the social challenges of increased parental and societal expectations and the navigation of changing peer groups [60–62]. Our sample represents a unique population of adolescents that have endured more physiological and social insults than is normative during childhood. Therefore, the overwhelming number of participants meeting criteria for a clinical concern is not surprising. Many survivors in the sample received treatments known to impact cognitive functioning. The comorbidity of concerns exhibited by some survivors post-CRT makes sense in an already vulnerable developmental period that may be further exacerbated by treatment effects. Few emotional concerns in this sample may be due to parent reporting, which has been shown to underestimate adolescent-perceived internalizing symptoms [63–65]. Therefore, our data may under-represent the emotional concerns of adolescent survivors in our sample.

A comprehensive assessment of psychological functioning across domains with data from multiple informants appears ideal for identifying survivors who require clinical attention. Referrals were associated with concerns on different types of attention and executive function measures (performance tasks and behavior rating scales) in both diagnostic groups. This is consistent with the vulnerability of these abilities to the deleterious effects of CNS-directed therapies [9–14]. The association between referrals and concerns identified on teacher-report measures underscores the importance of monitoring classroom behavior for ALL survivors, a group already known to be at risk for academic difficulties [6,66,67]. It is possible that inclusion of teacher-report measures in this study identified classroom concerns that had not been previously assessed for many survivors.

Surprisingly, no difference in the frequency of clinical concerns or referrals was identified between diagnostic groups. However, a history of CRT was associated with exhibiting a higher number of cognitive concerns. This is consistent with extensive research demonstrating cognitive risk with CRT [68] and highlights a vulnerable subgroup of survivors for whom long-term psychological follow-up is particularly critical. In both diagnostic groups, survivors with a higher number of problems were referred more often for follow-up, indicating the criteria for referral captured survivors suffering from the greatest psychological impairment.

Having a cognitive concern (Figure 2) or teacher-reported classroom difficulties was associated with referral for psychological follow-up among ALL survivors only. Although the difference was non-significant, more ALL survivors with cognitive concerns (61.9%) were referred for follow-up than BT survivors (42.3%). Our study evaluations may have detected cognitive late effects that emerged after a survivor’s last evaluation or lasting deficits that were no longer adequately addressed by recommendations from an evaluation conducted years earlier. In fact, at the time of study participation, ALL survivors had not received an updated psychological evaluation in over three years on average, while BT survivors were evaluated significantly more recently. Further, BT survivors in this sample were more likely to receive school services. These trends suggest ALL survivors may not receive psychological follow-up as regularly or as far out from treatment as BT survivors, leaving them at greater risk for experiencing unaddressed cognitive and educational needs.

Only one demographic indicator was found to be associated with clinical problems or referrals in this sample. Survivors from families with lower income experienced more psychological problems than their more affluent counterparts, consistent with previous reports of psychological vulnerabilities among disadvantaged survivors [17,20]. Specifically, ALL survivors with lower income exhibited more cognitive problems and received more referrals than the higher income group. Although few BT survivors in this sample fell into the lower-income category, they still exhibited significantly more behavioral and total problems across domains compared to higher-income BT survivors. The higher rate of problems among lower-income survivors may reflect premorbid differences that exist independent of the cancer experience. Alternatively, it may be an indicator of limits placed on a survivor’s recovery from treatment-related insults due to socioeconomic barriers (e.g., fewer educational supports). The higher rate of referral for lower-income ALL survivors suggests these families may have difficulty obtaining adequate support services in the community due to resource limitations.

It is important to consider the unique clinical environment of the pediatric research hospital where these study evaluations were conducted. This institution provides clinical services for patients regardless of their ability to pay and covers costs of travel and lodging for out-of-town families returning for follow-up care, removing financial and logistical barriers that could otherwise prevent lower-income families from returning to clinic for standard follow-up or for study participation. Thus, we may have been able to capture a truer estimate of the number of adolescent survivors needing psychological care by reducing the influence of privilege on study participation. Unfortunately, survivors with lower income (who are at increased risk for psychological problems according to our findings) may be least likely to receive routine psychological monitoring at other institutions that charge for services and are unable to assist with travel costs. Finally, even in a setting that conducts routine psychosocial screening and provides services free of charge, some families choose not to follow through with referrals for psychological evaluations or to engage local resources recommended by their providers. Income may impact these decisions even when services are free, such as when parents are forced to choose between being paid a day’s wages or taking the child to clinic. Further, when survivors are referred for psychological services in the community (outside of a cancer center), other barriers may emerge, including limitations in providers’ expertise with survivorship issues, availability of appropriate interventions for this population, and accessibility of adequate services to disadvantaged groups.

Certain methodological limitations must also be considered. The small sample size may have limited our ability to detect significant relationships with clinical factors (e.g., diagnosis, age at treatment). We examined numerous outcome measures per survivor in this exploration, and some clinical elevations across measures would be expected by chance. Still, the significant association between receiving a referral and having a higher number of clinical concerns indicates our methodology identified survivors experiencing the most clinical distress. Finally, it is possible that parents seeking help for symptomatic children were more likely to participate in this study, which would boost the occurrence of psychological problems in our sample, although the low refusal rate indicates the influence of such a selection bias should be minimal.

This is a secondary analysis, whereby extant data imposed certain limitations on our exploration. First, our measures were categorized conceptually into three gross domains: behavioral, cognitive, and emotional. Impairment in a single area of functioning can result in elevated scores on more than one measure or domain. For example, impaired attention functioning may result in clinical scores on both the Conners 3 (behavioral domain) and the CPT-II (cognitive domain). Second, measurement approaches differed across domains. The emotional domain was represented by the presence or absence of emotional disorders on the DICA-IV, potentially yielding a conservative measure of emotional concerns reflected in the low frequency of concerns identified in this domain relative to the others. Conversely, behavior rating scales may over-estimate the presence of concerns in the absence of a clinical interview to clarify symptoms and functional impairment. Third, our assessment of emotional concerns was based on parental report only. Future research should directly assess the experience of emotional difficulties from the adolescent’s perspective to better capture the frequency and severity of emotional problems in this population. Finally, for survivors requiring clinical referrals, we were unable to identify the reason for each referral (i.e., a previously unidentified concern versus inadequate services) based on the data available in this secondary analysis. As such, important questions remain regarding the frequency of late emerging clinical concerns versus the lack or inadequacy of services provided to survivors for psychological needs. These remain essential areas of investigation for future research efforts.

Further work is needed to fully understand the psychological needs of adolescent survivors of ALL and BT. Adolescence is a period of transition when individuals assume increasing levels of independence but continue to practice and refine their skills under parental guidance. Since survivors of childhood cancer are at risk for functional impairments in adulthood [69–71], it may be especially important to monitor survivors’ needs during adolescence when parents are still involved in navigating clinical care systems and resources are still available to survivors through pediatric centers and secondary education systems. This study suggests many adolescent survivors of ALL and BT experience psychological difficulties that are not adequately managed by current services, underscoring the need for long-term psychological monitoring. CRT and low income may place survivors at increased risk for post-treatment psychological problems that require intervention. Further, survivors of ALL, although not at increased risk for psychological concerns compared to BT survivors, may experience problems that go undetected or receive inadequate supports years after completion of treatment.

According to COG long-term follow-up guidelines, survivors of pediatric cancer should receive annual psychosocial assessment [34]. Notably, lower income is listed in the guidelines as a risk factor for psychosocial and mental health difficulties post-treatment, which is supported by our findings. Most survivors of ALL or BT received treatments that require baseline neuropsychological assessment with periodic reevaluation according to COG guidelines, yet the high frequency of unmet psychological needs identified in this study may indicate that these guidelines need to provide greater specificity regarding the quality of annual psychosocial assessments (e.g., focusing on cognitive functioning and behavioral measures of inattention and executive dysfunction, obtaining reports from parents and teachers) and the frequency of formal neuropsychological reevaluation (e.g., every 1–2 years through adolescence). Improving detection of and implementing targeted interventions for unmet psychological needs may increase the likelihood that adolescent survivors of ALL and BT will become psychologically healthy, productive, and independent adults.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported, in part, by the National Institute of Drug Abuse F32DA024503 (Lisa Schum [Kahalley], Principal Investigator), the NIH Cancer Center Support CORE Grant CA21765, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Abbreviations

- ADHD

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

- ALL

acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- BT

brain tumor

- CNS

central nervous system

- COG

Children’s Oncology Group

- CRT

cranial radiation therapy

Reference List

- 1.Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2004. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill JM, Kornblith AB, Jones D, et al. A comparative study of the long term psychosocial functioning of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia survivors treated by intrathecal methotrexate with or without cranial radiation. Cancer. 1998;82:208–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lorenzi M, McMillan AJ, Siegel LS, et al. Educational outcomes among survivors of childhood cancer in British Columbia, Canada: report of the Childhood/Adolescent/Young Adult Cancer Survivors (CAYACS) Program. Cancer. 2009;115:2234–2245. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stehbens JA, Kaleita TA, Noll RB, et al. CNS prophylaxis of childhood leukemia: what are the long-term neurological, neuropsychological, and behavioral effects? Neuropsychol Rev. 1991;2:147–177. doi: 10.1007/BF01109052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moleski M. Neuropsychological, neuroanatomical, and neurophysiological consequences of CNS chemotherapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2000;15:603–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterson CC, Johnson CE, Ramirez LY, et al. A meta-analysis of the neuropsychological sequelae of chemotherapy-only treatment for pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:99–104. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ris MD, Noll RB. Long-term neurobehavioral outcome in pediatric brain-tumor patients: review and methodological critique. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1994;16:21–42. doi: 10.1080/01688639408402615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fossen A, Abrahamsen TG, Storm-Mathisen I. Psychological outcome in children treated for brain tumor. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1998;15:479–488. doi: 10.3109/08880019809018309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmquist LA, Scott J. Treatment, age, and time-related predictors of behavioral outcome in pediatric brain tumor survivors. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2002;9:315–321. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langer T, Martus P, Ottensmeier H, Hertzberg H, Beck JD, Meier W. CNS late-effects after ALL therapy in childhood. Part III: neuropsychological performance in long-term survivors of childhood ALL: impairments of concentration, attention, and memory. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;38:320–328. doi: 10.1002/mpo.10055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lockwood KA, Bell TS, Colegrove RW. Long-term effects of cranial radiation therapy on attention functioning in survivors of childhood leukemia. J Pediatr Psychol. 1999;24:55–66. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodgers J, Horrocks J, Britton PG, Kernahan J. Attentional ability among survivors of leukaemia. Arch Dis Child. 1999;80:318–323. doi: 10.1136/adc.80.4.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maddrey AM, Bergeron JA, Lombardo ER, et al. Neuropsychological performance and quality of life of 10 year survivors of childhood medulloblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2005;72:245–253. doi: 10.1007/s11060-004-3009-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson V, Godber T, Smibert E, Ekert H. Neurobehavioural sequelae following cranial irradiation and chemotherapy in children: an analysis of risk factors. Pediatr Rehabil. 1997;1:63–76. doi: 10.3109/17518429709025849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noll RB, Kupst MJ. Commentary: the psychological impact of pediatric cancer hardiness, the exception or the rule? J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:1089–1098. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eiser C, Hill JJ, Vance YH. Examining the psychological consequences of surviving childhood cancer: systematic review as a research method in pediatric psychology. J Pediatr Psychol. 2000;25:449–460. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/25.6.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patenaude AF, Kupst MJ. Psychosocial functioning in pediatric cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30:9–27. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lund LW, Schmiegelow K, Rechnitzer C, Johansen C. A systematic review of studies on psychosocial late effects of childhood cancer: structures of society and methodological pitfalls may challenge the conclusions. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56:532–543. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stam H, Grootenhuis MA, Last BF. Social and emotional adjustment in young survivors of childhood cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2001;9:489–513. doi: 10.1007/s005200100271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuemmeler BF, Elkin TD, Mullins LL. Survivors of childhood brain tumors: behavioral, emotional, and social adjustment. Clin Psychol Rev. 2002;22:547–585. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gurney JG, Krull KR, Kadan-Lottick N, et al. Social outcomes in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2390–2395. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zebrack BJ, Gurney JG, Oeffinger K, et al. Psychological outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood brain cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:999–1006. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zebrack BJ, Zeltzer LK, Whitton J, et al. Psychological outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood leukemia, Hodgkin’s disease, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatrics. 2002;110:42–52. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mackie E, Hill J, Kondryn H, McNally R. Adult psychosocial outcomes in long-term survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and Wilms’ tumour: a controlled study. Lancet. 2000;355:1310–1314. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levin NW, Brown RT, Pawletko TM, Gold SH, Whitt JK. Social skills and psychological adjustment of child and adolescent cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2000;9:113–126. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(200003/04)9:2<113::aid-pon432>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radcliffe J, Bennett D, Kazak AE, Foley B, Phillips PC. Adjustment in childhood brain tumor survival: child, mother, and teacher report. J Pediatr Psychol. 1996;21:529–539. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/21.4.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyer EA, Kieran MW. Psychological adjustment of ‘surgery-only’ pediatric neuro-oncology patients: a retrospective analysis. Psychooncology. 2002;11:74–79. doi: 10.1002/pon.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rutter M, Graham P, Chadwick OF, Yule W. Adolescent turmoil: fact or fiction? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1976;17:35–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schultz KA, Ness KK, Whitton J, et al. Behavioral and social outcomes in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3649–3656. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krull KR, Huang S, Gurney JG, et al. Adolescent behavior and adult health status in childhood cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:210–217. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0123-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Servitzoglou M, Papadatou D, Tsiantis I, Vasilatou-Kosmidis H. Psychosocial functioning of young adolescent and adult survivors of childhood cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:29–36. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0278-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clinton-McHarg T, Carey M, Sanson-Fisher R, Shakeshaft A, Rainbird K. Measuring the psychosocial health of adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer survivors: a critical review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:25. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones BL. Promoting healthy development among survivors of adolescent cancer. Fam Community Health. 2008;31 (suppl 1):S61–S70. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000304019.98007.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Children’s Oncology Group. [Accessed June 6, 2011.];Long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancers. 2008 http://www.childrensoncologygroup.org/disc/le/

- 35.Kahalley LS, Tyc VL, Wilson SJ, et al. Adolescent cancer survivors’ smoking intentions are associated with aggression, attention, and smoking history. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:123–131. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0149-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conners CK. Conners 3rd Edition Manual. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Multi-Health Systems Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gioia GA, Isquith PK, Guy SC, Kenworthy L. BRIEF—Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function. Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reich W, Welner Z, Herjanic B. The Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents-IV. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rogers R. Handbook of Diagnositc and Structured Interviewing. Guilford Press; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Welner Z, Reich W, Herjanic B, Jung KG, Amado H. Reliability, validity, and parent-child agreement studies of the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (DICA) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1987;26:649–653. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198709000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children - Fourth Edition Technical and Interpretive Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. 4. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. 3. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wechsler D. Technical Manual. 3. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer JH. Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mattson SN, Goodman AM, Caine C, Delis DC, Riley EP. Executive functioning in children with heavy prenatal alcohol exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:1808–1815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wodka EL, Loftis C, Mostofsky SH, et al. Prediction of ADHD in boys and girls using the D-KEFS. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2008;23:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Conners CK MHS Staff. Conners’ Continuous Performance Test (CPT II) Computer Programs for WindowsTM Technical Guide and Software Manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anderson VA, Anderson P, Northam E, Jacobs R, Mikiewicz O. Relationships between cognitive and behavioral measures of executive function in children with brain disease. Child Neuropsychol. 2002;8:231–240. doi: 10.1076/chin.8.4.231.13509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Conklin HM, Salorio CF, Slomine BS. Working memory performance following paediatric traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2008;22:847–857. doi: 10.1080/02699050802403565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McAuley T, Chen S, Goos L, Schachar R, Crosbie J. Is the behavior rating inventory of executive function more strongly associated with measures of impairment or executive function? J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2010;16:495–505. doi: 10.1017/S1355617710000093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vriezen ER, Pigott SE. The relationship between parental report on the BRIEF and performance-based measures of executive function in children with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Child Neuropsychol. 2002;8:296–303. doi: 10.1076/chin.8.4.296.13505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rapport MD, Kofler MJ, Bolden J, Sarver DE. Treatment Research. In: Hersen M, Gross AM, editors. Handbook of Clinical Psychology, vol 2: Children and Adolescents. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2008. pp. 386–425. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication--Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sisk CL, Zehr JL. Pubertal hormones organize the adolescent brain and behavior. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2005;26:163–174. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nelson EE, Leibenluft E, McClure EB, Pine DS. The social re-orientation of adolescence: a neuroscience perspective on the process and its relation to psychopathology. Psychol Med. 2005;35:163–174. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brown BB, Mounts N, Lamborn SD, Steinberg L. Parenting practices and peer group affiliation in adolescence. Child Dev. 1993;64:467–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dekoviæ M, Noom MJ, Meeus W. Expectations regarding development during adolescence: Parental and adolescent perceptions. JYouth Adolescence. 1997;26:253–272. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ryan AM. The peer group as a context for the development of young adolescent motivation and achievement. Child Dev. 2001;72:1135–1150. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT. Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychol Bull. 1987;101:213–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cantwell DP, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Correspondence between adolescent report and parent report of psychiatric diagnostic data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:610–619. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199705000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sourander A, Helstela L, Helenius H. Parent-adolescent agreement on emotional and behavioral problems. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34:657–663. doi: 10.1007/s001270050189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reddick WE, Shan ZY, Glass JO, et al. Smaller white-matter volumes are associated with larger deficits in attention and learning among long-term survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2006;106:941–949. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Spiegler BJ, Kennedy K, Maze R, et al. Comparison of long-term neurocognitive outcomes in young children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with cranial radiation or high-dose or very high-dose intravenous methotrexate. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3858–3864. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.9055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mulhern RK, Butler RW. Neurocognitive sequelae of childhood cancers and their treatment. Pediatr Rehabil. 2004;7:1–14. doi: 10.1080/13638490310001655528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kirchhoff AC, Leisenring W, Krull KR, et al. Unemployment among adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Med Care. 2010;48:1015–1025. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181eaf880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mody R, Li S, Dover DC, et al. Twenty-five-year follow-up among survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Blood. 2008;111:5515–5523. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-117150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Armstrong GT, Liu Q, Yasui Y, et al. Long-term outcomes among adult survivors of childhood central nervous system malignancies in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:946–958. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]