Abstract

With the adoption of national health insurance in 1977, Korea has been utilizing fee-for-service payment with contract-based healthcare reimbursement system in 2000. Under the system, fee-for-service reimbursement has been accused of augmenting national healthcare expenditure by excessively increasing service volume. The researcher examined in this paper two major alternatives including diagnosis related group-based payment and global budget to contemplate the future of reimbursement system of Korean national health insurance. Various literature and preceding studies on pilot project and actual implementation of Neo-KDRG were reviewed. As a result, DRG-based payment was effective for healthcare cost control but low in administrative efficiency. Global budget may be adequate for cost control and improving the quality of healthcare and administrative efficiency. However, many healthcare providers disagree that excess care arising from fee-for-service payment alone has led to financial deterioration of national health insurance and healthcare institutions should take responsibility with global budget payment as an appropriate solution. Dissimilar payment systems may be applied to different types of institutions to reflect their unique attributes, and this process can be achieved step-by-step. Developing public sphere among the stakeholders and striving for consensus shall be kept as collateral to attain the desirable reimbursement system in the future.

Keywords: National Health Insurance, Reimbursement System, Fee-for-service Payment, DRG-Based Payment, Global Budget Payment, Neo-KDRG-Based Payment

INTRODUCTION

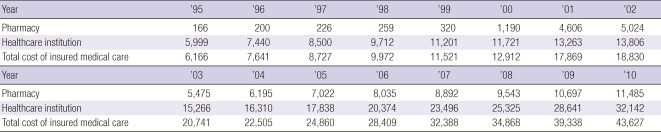

In conjunction with the adoption of national health insurance in 1977, Korea has been utilizing fee-for-service reimbursement system where providers receive payment for each service rendered. Since 1995, the cost of insured medical care for healthcare institutions has risen by 29% on average each year (1). When this figure is supplemented by the cost for pharmacies, the total cost of insured medical care is observed to increase by 40.5% each year (1) as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Annual trend of cost of insured medical care for healthcare institutions and pharmacies 〈Amount in KRW billion〉

Source: National Health Insurance Corporation (NHIC), Statistical Yearbook.

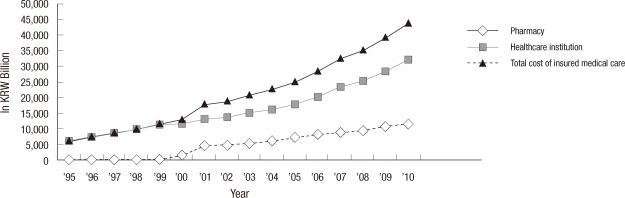

However, the latter shall take into account the effect of 'separation of prescribing and dispensing drugs' implemented between 2000 and 2001. The annual trend of cost of insured medical care for both healthcare institutions and pharmacies as well as the effect of separation of prescribing and dispensing drugs are comprehensively illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Annual trend of cost of insured medical care for healthcare institutions and pharmacies in Korea. Source: National Health Insurance Corporation (NHIC), Statistical Yearbook.

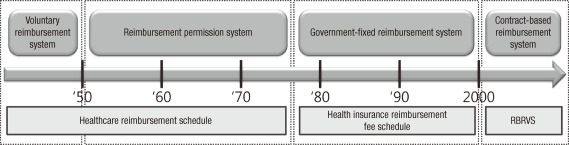

Health insurance law in Korea was revised to national health insurance law in 2000 with an introduction of contract-based healthcare reimbursement system. Prior to 2000, the reimbursement methods in Korea went through a series of changes from voluntary reimbursement system and reimbursement permission system to government-fixed reimbursement system (2). First, voluntary reimbursement system was in effect from the period of Japanese colonial rule to 1951 in which healthcare reimbursement was voluntarily determined by healthcare institutions. During this period, the healthcare market retained monopolistic structure, and thus reimbursement was relatively very high when compared to general price level. Second, reimbursement permission system was in effect from 1951 to 1976 where monopolistic provider voluntarily determined the reimbursement level in the healthcare market. Third, government-fixed reimbursement system was in effect from 1977 to 1999. As noted earlier, health insurance law was revised to national health insurance law in 2000 and the reimbursement system changed from the existing government-fixed system to a contract-based system. This transition of reimbursement systems is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Transition of reimbursement methods in Korea.

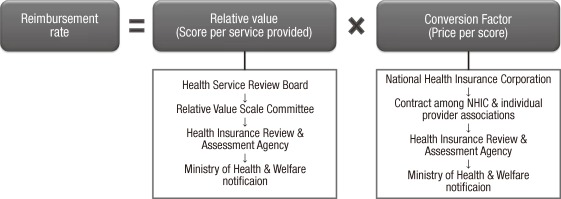

Simultaneously, the existing fee schedule was discarded and relative value scale was newly adopted. Under the relative value scale system, reimbursement for each service rendered is determined by multiplying relative value (i.e. value score) by conversion factor (i.e. price per value score). Beginning in 2007, relative values have been established by National Health Insurance Corporation (NHIC) with conversion factors determined through negotiations among NHIC, Ministry of Health & Welfare, and individual provider associations (3) as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Determination of relative value scale and conversion factor for reimbursement in Korea.

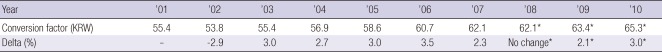

If these associations successfully established reimbursement contract with NHIC, the level and rate of reimbursement for that particular year would be finalized as agreed upon. Otherwise, they would be put on vote. Since the value scores of specific services provided are fixed, only the conversion factors may be subject to change year by year, and Table 2 below shows the transition of conversion factors from 2001 to 2010.

Table 2.

Transition of conversion factors in Korea 2001-2010

*Denotes final reimbursement for clinic-level healthcare organizations.

Contract-based reimbursement system in Korea, however, has indicated constraints and raised disputes among different provider groups to date mainly due to the origin of supporting data for analysis (3). A variety of mechanisms have been suggested to deduce appropriate conversion factors and reimbursement rates, but the majority of the analysis methods rely on financial statements voluntarily submitted by corresponding provider institutions including hospitals and clinics. Consequently, stakeholders involved in reimbursement contract ended up questioning the transparency and accuracy of the specific rates suggested by the opposite party, thus often leading to a rupture of negotiations.

Therefore, the researcher in this study pays close attention to the effect of fee-for-service reimbursement on national health insurance in Korea. As discussed above, the increase in the healthcare reimbursement rate has caused the cost of insured medical care to rise to a significant degree. Furthermore, fee-for-service reimbursement in Korea has been accused by a variety of stakeholders of augmenting national healthcare expenditure by excessively increasing healthcare service volume. With this taken into account, the researcher examines in this paper the two major alternatives, which are 'diagnosis related group (DRG)-based payment system' and 'global budget system', and forecasts the future of reimbursement system of Korean national health insurance.

BACKGROUND

In order to alleviate the aforementioned issues posed by fee-for-service reimbursement, a number of reimbursement alternatives have been given careful consideration by the decision-makers in Korea. Among a number of alternatives available, DRG-based payment and global budget systems have most frequently been discussed in Korea to date.

Diagnosis related group (DRG)-based payment system

The Healthcare Reform Commission under the Ministry of Health & Welfare proposed to phase in the DRG-based payment system in Korea in 1994 in order to overcome the existing limitations of fee-for-service payment (4). DRG-based payment system is a form of case-based prospective payment system (PPS) under which payment is based on particular diagnoses determined by physicians. Each DRG categorizes patients who share uniform clinical profiles and requisite resources. In the US, approximately 990 categories of DRGs (modified in 2010) are applied to hospital inpatient services (5). Major European countries are reported to prevent hospitals from evading patients with severe conditions and promote efficient usage of resources by utilizing inpatient DRGs when allocating budget to hospitals through global budget system. In case of Korea, Hospital Research Institute at Seoul National University initially developed a Korean version of DRGs, namely KDRG, to improve the overall review process of health insurance claims (6). Subsequently, the KDRG was refined in 1991 based on the refined DRG of the US, which considered the severity of diseases and conditions, and was applied to a specified group of diseases on a trial basis.

Under the case-based payment system, gross medical fee is determined by 'Rate(s) per case X Total number of cases' where the providers can only increase the number of cases, and thus the cost of medical care is likely to decrease. In fact, MEDPAC reported in 2002 a 32.2% decrease in the average length of stay (LOS) of hospitals between 1989 and 1999 (7). Meanwhile, Germany adopted Australian DRG in 2004 and experienced a negative growth of national healthcare expenditure in the years to follow (5). Therefore, case-based payment system such as DRGs may be seen as a valid cost cutting mechanism which has the ability to eliminate the factors of excessive care commonly observed under the fee-for-service payment system.

With regard to the quality of healthcare, no cases have been reported that the application of DRGs degraded the quality of care provided in the US (8, 9). In addition, case-based payment system is very convenient in terms of administration, and DRG-based payment system prevents the providers from charging excessively when compared to fee-for-service payment system. However, the preventive measure under the DRG-based payment system requires a substantial amount of screening and monitoring. As Charles and Weber noted, it is difficult to conclude that the DRG-based system is simply better than the fee-for-service system as far as administrative costs are concerned (10).

Global budget system

The recent financial deterioration of Korean national health insurance after the integration of national health insurance and separation of prescribing and dispensing drugs has demanded a change of reimbursement system from fee-for-service payment to global budget. Global budget is used by many European countries showing a stable increase rate of healthcare expenditure except Portugal. Among the Asian countries, Taiwan is identified to apply global budget to all of the healthcare institutions. In Taiwan, the budget increased by 3.5% in 2009 compared to that of the previous year. Furthermore, Taiwan simultaneously applies the soft-cap floating point value which is similar to the sustainable growth rate (SGR) used in the US (11).

A good example of global budget application is the method used in the Netherlands. In the Netherlands, budget for negotiation is determined by the following equation (11), in which capital expenditure is subject to repayment in 50 yr and is reimbursed on a daily basis.

Budget for negotiation for hospitals

= (No. of regional patients X Tariff) + (No. of approved beds X Tariff) + (No. of approved specialist unit X Tariff) + (No. of cases of hospital inpatients X Tariff) + (Total LOS X Tariff) + (No. of cases of hospital outpatients X Tariff) + (No. of special treatments X Tariff) + (No. of cases of day surgery X Tariff)

Since budget negotiation is a relatively simple method, administrative cost of global budget can be significantly reduced compared to that of fee-for-service payment. However, the providers may substitute by low-cost services, thus leading to a possible degradation of the quality of services provided. In case where variable budget system is used for quality control as witnessed in the Netherlands, the cost of medical care may increase again.

KDRG-BASED PAYMENT SYSTEM IN KOREA

As discussed earlier in this paper, the Healthcare Reform Commission under the Ministry of Health & Welfare proposed to phase in the DRG-based payment system in Korea in 1994 in order to overcome the existing limitations of fee-for-service payment. Accepting the proposition, the government carried out a KDRG (DRG, hereafter)-based system pilot project for eight groups of surgical diseases and procedures (appendectomy, tonsillotomy, hernia, cesarian section, hysterectomy, eutocia, cataract, and hemorrhoid) from February 1997 to 2001 (12). The results of the pilot project can be examined in three domains including cost, health services, and quality. Here, health services domain can further be broken down into three sub-domains of changes in service volume and LOS, provision of specified tests and treatments, and transition to outpatient services. In this part of the study, the researcher reviewed these results of the pilot project reported by the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service (13).

COST DOMAIN

The first set of results from the DRG-based system pilot project focused on the cost effect of the system. First, a total of 318 females among the 99 females in 1997, 119 in 1998, and 100 in 1999 who were discharged from a general hospital after receiving cesarian section were selected to examine the changes in the amount of self-payment (out-of-pocket) as well as of the insurer's payment (13). As a result, the actual amount self-paid by the patients dropped each year to KRW 228,800 in 1997, KRW 188,200 in 1998, and KRW 191,300 in 1999. On the contrary, the amount paid by the insurers increased from KRW 537,200 to KRW 810,100 in 1998 and KRW 831,200 in the following year. These results were all statistically significant with P < 0.001. Second, 100 females in 1999 and the same number of females in 2000 who received cesarian section at a general hospital in 1997 were chosen (13). The amount of self-payment before the pilot project was KRW 345,825 in 1997 with the amount after the pilot project in KRW 170,305 in 1999 and 2000, thus showing a substantial decrease after the project was carried out. This might have been caused by the change in reimbursement structure after the pilot project that excluded voluntary uninsured elements. In addition, the amount of insurers' payment before the pilot project was KRW 721,066 in 1997 with the amount after the pilot project in KRW 677,843 in 1999 and 2000, thus showing a decrease after the project was carried out with statistical significance (P < 0.01). According to these results, the implementation of the DRG-based system pilot project had a rather inconsistent impact on payment accuracy, insurer's payment, and patient's self-payment. Depending on the specific groups of diseases or health services provided, the total amount of health expenditure, insurer's payment, and patient's self-payment increased in some cases while decreasing in others.

HEALTH SERVICES DOMAIN 1

The second set of results from the pilot project focuses on the health services domain of DRG adoption in Korea. In specific, this domain examines the changes in service volume and LOS. A total of 318 females among the 99 females in 1997, 119 in 1998, and 100 in 1999 who were discharged from a general hospital after receiving cesarian section were selected again to analyze the changes both in health service volume and LOS before and after the pilot project took place by calculating average costs and LOS of inpatient examinations, injections, and oral medications affected by physician's diagnosis (13). As a result, service volume decreased by 25% in the first year and 29% in the second year after the pilot project was carried out. The LOS also decreased by 1% in the first year and 6% in the second year after the project took place. According to Lee et al. (14), the average LOS of monocular crystalline lens surgery decreased by 1.6 days (32.6%) from 4.9 days to 3.3 days, while that of binocular crystalline lens surgery decreased by 1.8 days (23.5%) from 7.6 days to 5.8 days. Furthermore, the cost, affected by service volume change, of monocular crystalline lens surgery dropped by KRW 174,344 from KRW 1,218,233 to KRW 1,043,889, while that of binocular crystalline lens surgery decreased by KRW 229,801 from KRW 2,303,907 to KRW 2,074,106. Therefore, significant differences were observed before and after the pilot project. Second, 100 females in 1999 and the same number of females in 2000 who received cesarian section at a general hospital in 1997 were chosen again, and the average LOS decreased from 7.6 days in 1997 to 6.7 days in 1999 and 2000 with statistical significance (P < 0.01) (13). In conclusion, the implementation of the DRG-based system pilot project had a positive effect on the health services domain 1 that both of the service volume and LOS decreased following the implementation.

HEALTH SERVICES DOMAIN 2

The third set of results from the pilot project focuses on the health services domain of DRG adoption in Korea. In specific, this domain explores provision of specified tests and treatments. Among the 318 females who were discharged from a general hospital after receiving cesarian section from 1997 to 1999, intravenous injection decreased by 5% in the first year and 11% in the second year after the pilot project (13). On the contrary, the period of oral antibiotics application increased by 8% in the first year and 10% in the second year after the project. Service volume of intravenous injection decreased while that of oral antibiotics increased. Lee et al. (14) reported that the days of use of antibiotics injection decreased by 36.5% for monocular crystalline lens surgery while it decreased by 19.4% for binocular crystalline lens surgery. Among the 200 females chosen in 1999 and 2000 who received cesarian section at a general hospital in 1997, the average drug price of oral antibiotics before the project was KRW 37,044, and the price dropped to KRW 20,294 after the project (13). In all specialty areas, the amount of antibiotics used per one inpatient decreased. These results imply that the DRG-based system pilot project retained weak control over the provision behavior of certain tests and treatments.

HEALTH SERVICES DOMAIN 3

The fourth set of results from the pilot project focuses on the health services domain of DRG adoption in Korea. In specific, this domain examines transition to outpatient services. Lee et al. (14) reported that number of outpatient visit prior to hospitalization is decreased while the total medical fee and fee per visit are increased for monocular crystalline lens surgery. Furthermore, number of outpatient visits, total medical fee, and fee per visit all decreased after hospital discharge. In case of binocular crystalline lens surgery, number of outpatient visits, total medical fee, and fee per visit all increased prior to hospitalization. Number of outpatient visits and total medical fee decreased and fee per visit increased after hospital discharge. Among the 200 females chosen in 1999 and 2000 who received cesarian section at a general hospital in 1997, the average number of outpatient visits was 1.3 in 1997 and 1.1 in 1999 and 2000 showing a slight decrease after the pilot project (13). This result conflicted with the evaluation conducted by Jung and Lee (15) that reported a 6.9% increase for the same variable. In conclusion, the DRG-based system pilot project retained a variable effect on the frequency of patient visits to outpatient services prior to and discharge from inpatient services.

QUALITY DOMAIN

The last set of results from the pilot project focuses on the changes in quality upon DRG adoption. Yim et al. (16) evaluated the effect of DRG system on the quality of healthcare by comparing 122 individuals who received surgical procedures under fee-for-service and 258 individuals who received similar services under DRG across 40 different healthcare institutions. As a result, no significant difference was observed between the conduct rates of required tests before and after surgery, and the groups under DRG system were shown to have higher quality of healthcare (P < 0.05). The LOS of healthcare institutions with a longer period (one to two years) of DRG application was shorter than that of the institutions with a short history of application (13). Lee et al. (14) reported no significant difference in the incidence rate of complications within one month after surgery. In conclusion, these results implied that the DRG-based payment system does not significantly degrade the quality of healthcare, and the groups of diseases under the DRG-based system may reflect higher quality of healthcare than the groups without any DRG application.

ACTUAL IMPLEMENTATION

Upon the results obtained from the DRG-based system pilot project, healthcare institutions were given the option to choose either the fee-for-service payment system or DRG-based PPS for four specialty areas and eight groups of diseases and conditions from January 2002. By 2007, more than 2,350 institutions participated in the actual implementation. However, the majority of these institutions was clinic-level institutions, and advanced tertiary institutions, which require actual application of the system, did not participate or withdrew from the program leading to the failure of DRG-based payment system overall. In particular, the healthcare sector already was pessimistic toward the DRG system since its implementation, and this behavior has been basically identical to date. The healthcare sector in Korea has been opposing the adoption of DRG-based system for the following principle reasons.

The adoption of the DRG-based payment system has not reflected the opinions of the healthcare sector, the relevant party, and introducing a foreign program developed in a dissimilar environment is likely to cause side effects.

Just as the fee-for-service system caused a rise in the gross healthcare expenditure in Korea by distorting care patterns where reimbursement is significantly low, the DRG-based payment system is also likely to bring about its own problems. The potential problem in the case of DRG would be 'under-care'.

Degradation of the quality of healthcare and restraints on the development of innovative medical technology or materials are anticipated under DRG.

NEO-KDRG-BASED PAYMENT SYSTEM IN KOREA

As discussed earlier, the Korean government phased in the adoption of DRG-based payment system starting with a pilot project in 1997 eventually leading to the actual implantation of the program in 2002. However, while lacking a social consensus, the existing DRG model was limited only to certain groups of diseases and conditions and applying the system for the healthcare institutions remained purely 'optional'. This model was a case-based model with low flexibility focusing on relatively simple diseases, and thus could not be applied to other diseases with great deviations in the care provided. Particularly, the existing model could not ensure the quality of healthcare provided to patients with high severity and complexity that a new mechanism became necessary. In response to these issues, the government recently developed the 'Neo-KDRG (hereafter DRG)-based payment system'.

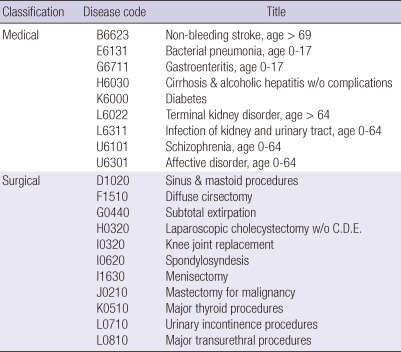

Neo-DRG-based payment model

Neo-DRG-based payment model has been developed as an effective alternative to alleviate the limitations of the existing fee-for-service system and DRG model in Korea. The model was designed initially for 20 groups of diseases and conditions, and the government carried out a Neo-DRG-based payment pilot project by applying the model to Ilsan Hospital which is an insurer hospital from April 2009 (15). The specific diseases included in the Neo-DRG payment model are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Diseases & conditions included in the Neo-DRG pilot project

Evaluation on Neo-DRG pilot project

Under PPS, the providers strive to reduce resource consumption since the level of reimbursement for the services provided is fixed in advance. This facilitates controlling healthcare expenditure but it may lead to 'under-care' at the same time. Under any payment system, reimbursement for resource utilization becomes asymmetric if bundling of payment unit becomes too big while the limitations related with fee-for-service arise if it becomes too small. Neo-DRG-based payment system is indeed a mixture of PPS and fee-for-service which shows a significant difference compared to the existing DRG model and fee-forservice system. The issue is, then, how and to what extent we are going to differentiate and use the two systems simultaneously.

The recent Neo-DRG model enables us only to identify the accuracy of healthcare reimbursement and changes in self payment and insurers' payment, but it cannot support analyzing the specific behaviors behind health service provision or transition from the bundling domain to the per-service domain. The medical staff at Ilsan Hospital may have less resistance toward Neo-DRG model itself than those at other institutions; however, Ilsan Hospital is a public insurer hospital which makes identifying the changes in general care behavior very difficult. Given the current conditions, we can re-evaluate the model on the following criteria.

Is the level of reimbursement set as appropriate?

Is the provider behavior induced to appropriate direction?

Is the model technically well-designed?

The Korean government is currently planning on developing yet another new model which will be applied to more than 70% of the entire population of inpatients through expanding the applicable groups of diseases and conditions. Furthermore, these disease groups will be used in four public regional-hospitals then in 40 additional public regional-hospitals following the recent Neo-DRG pilot project which ended in June 2010. However, the healthcare sector and academia continue to hold a negative view on Neo-DRG-based payment system, and various stakeholders including the government, NHIC, HIRA, and hospitals are organizing their own task force and advisory units for continued discussion in-depth.

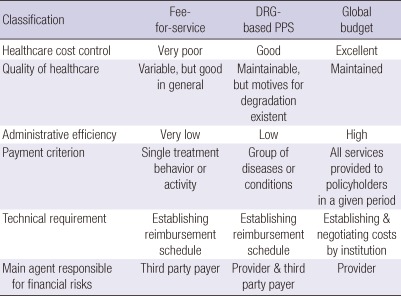

COMPARATIVE EVALUATION ON ALTERNATIVES

The attributes of the two reimbursement alternatives can be examined and cross-compared on two dimensions including the evaluation on performance of the reimbursement system and operation of the system. First, DRG-based payment as part of PPS is effective for healthcare cost control. Although certain motives exist for quality degradation, the quality is reported to be maintained to a certain degree in the aforementioned empirical studies. In addition, the administrative efficiency of the system is low because its screening function must be reinforced. With regard to its operation, reimbursement schedule must be established since rate(s) per case is determined in advance by groups of diseases under the DRG-based system.

On the contrary, global budget may be evaluated as adequate for controlling the cost of medical care and improving the quality of healthcare and administrative efficiency. In terms of operation of the system, the total amount of medical cost is fixed in advance under the global budget system. Furthermore, the providers retain financial responsibilities since both of the providers and third party payers can confirm the total amount. As shown in the case of Taiwan, global budget is applicable across all types of healthcare institutions. The attributes discussed above are briefly summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comp arison among major reimbursement systems

Furthermore, with regard to the global budget payment system, the hospital industry in Korea believes that the current reimbursement system is not the sole factor of the recent increase in national health expenditure; rather, this rapid increase has resulted from an increase in societal needs for healthcare including expanding national needs for overall health, development of medical technology, population aging, and expanding coverage of national health insurance (15). The majority of healthcare providers, hospitals in specific, are opposed to the claim that excess care arising from fee-for-service payment has led to the financial deterioration of national health insurance and that, as a direct consequence, healthcare institutions must take full responsibility with global budget payment as an appropriate solution. Therefore, the healthcare industry in Korea demands that, based on the experiences of major countries that have introduced global budget payment, countermeasures for the potential side effects such as 'under-care' of healthcare institutions, evading patients with severe diseases or conditions, distortion of medical practice, degradation of quality of care, and loss of motives for medical development must first be concretely established. In addition, now is the time to focus on further enhancing the quality of healthcare, and, in this respect, they argue that the fee-for-service payment system must be maintained until appropriate care is delivered to the nation.

CONCLUSION

Subsequent to reviewing preceding studies and examining the status quo with regard to evolving healthcare reimbursement system in Korea, the researcher believes that applying a specific payment system uniformly across all types of healthcare institutions retains high risk. Rather, different payment systems can be applied to different types of institutions so that they may function as intended in accordance with unique attributes of each category. Clinic-level institutions mainly focus on treating simple diseases or conditions and managing chronic diseases (17), and thus we can consider applying 'target health expenditure system' to this category of healthcare institutions. On the other hand, hospitals in general focus on providing services to diseases that require hospitalization, and DRG-based payment system can be an appropriate alternative. In this case, the DRG-based system would be further divided into outpatient DRG system and inpatient DRG system. For the 44 advanced tertiary hospitals operating across the nation, the researcher recommends global budget system in order to help alleviate the tilting phenomenon toward large-sized healthcare institutions. This phenomenon is especially predominant in Korea where patients with even minor diseases and conditions such as cold, sprain or otitis media tend to prefer receiving care from large hospitals rather than from local primary care institutions based on inappropriate patient mentality. In reality, these patients most likely do not require comprehensive medical specialties and high-end equipment that the large hospitals typically offer, and their distorted preference has been identified to exacerbate the tilting phenomenon of the overall patient pool toward large-sized healthcare institutions. With this taken into account, global budget system may be a helpful solution to the advanced tertiary hospitals in Korea.

In addition, the application of healthcare reimbursement system can be achieved step-by-step. One example is to apply the target health expenditure system to clinics and global budget system to advanced tertiary hospitals first, then subsequently applying outpatient and inpatient DRG-based payment systems to the remaining categories of hospitals. Prior to introducing the DRG-based system, the target health expenditure system may also be applied to general hospitals on a temporary basis. The target health expenditure system and global budget system can be introduced rather promptly under the given conditions; however, DRG-based system is likely to consume more time for the actual adoption since it requires further research on bundling payment units and various other issues discussed in this study.

Various alternatives under discussion for the prospective reimbursement system in Korea lack the possibility for social consensus among the stakeholders with providers in particular. More importantly, issues regarding national health insurance encompass complex political factors that make this possibility even lower. The decision makers who experienced the physicians' strike during the initial stage of separation of prescribing and dispensing drugs have been reluctant to push ahead with a drastic reform. However, the issues of healthcare in Korea are becoming significant political agenda as witnessed in major developed countries, and the national healthcare expenditure is likely to rise consistently in the future. Is there room for change as far as the national health insurance reimbursement system in Korea is concerned? The researcher strongly believes so. However, developing public sphere among the stakeholders and striving for consensus shall be kept as collateral to attain the desirable system in reality.

Limitation

The researcher endeavored to anticipate and suggest the future reimbursement system of Korean National Health Insurance in this study by focusing on two of the most frequently discussed alternatives. However, the primary mechanism to achieve the goal of the study was to indirectly review closely the results of the preceding studies and tests with regard to these available alternatives. In order to deduce directly the appropriate reimbursement systems, which fit the attributes of Korean National Health Insurance, and suggest prospective direction, empirical analyses using up-to-date data shall further be conducted in the future.

References

- 1.Korea National Health Insurance Corporation. National health insurance statistics yearbook. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yim K, Chae Y, Choi J. Korean Medical Association. 2008. A study on health reimbursement process and methodology, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korea National Health Insurance Corporation. A study on conversion factors for types of healthcare institutions. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korean Institute of Hospital Management. Improving reimbursement per types of institutions, Korea. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim Y. Problems of fee-for-service reimbursement system and alternatives. J Korean Health Secur. 2010;9:8–24. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seoul National University. A study on cost analysis using management analysis data of hospitals, Korea. Seoul National University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Office of Inspector General. Medicare hospital prospective payment system: how DRG rates are calculated and updated. USA Department of Health & Human Services MEDPAC; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sloan FA, Morrisey MA, Valvona J. Effects of the medicare prospective payment system on hospital cost containment: an early appraisal. Milbank Q. 1988;66:191–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DesHarnais S, Chesney J, Fleming S. Trends and regional variations in hospital utilization and quality during the first two years of the prospective payment system. Inquiry. 1988;25:374–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charles N, Weber A. Social health insurance: a guidebook for planning. USA: WHO-ILO; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korea National Health Insurance Corporation. Healthcare systems of major countries. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministry of Health & Welfare, National Health Insurance Corporation, Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service. Guidelines to neo-DRG-based payment pilot project. Korea National Health Insurance Corporation. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korea Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service. An evaluation on neo-KDRG-based payment system pilot project. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee M, Lee Y, Goh G. The change of medical care pattern and cost of cataract surgery by the DRG payment system in a general hospital. Korean J Hosp Manage. 2005;10:48–70. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jung S, Lee Y. Korean Hospital Association. 2010. A trend of national health insurance reimbursement systems and improvement, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yim J, Kwon Y, Hong D, Kim C, Kim Y, Shin Y. Changes in the quality of healthcare in cesarian section after DRG adoption. J Prev Med. 1991;34:347–353. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park Y. Korean Medical Association. 2010. An analysis on clinic management. [Google Scholar]