Abstract

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy and safety of adjunctive mosapride citrate for bowel preparation before colonoscopy.

METHODS: We conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with mosapride in addition to polyethylene glycol (PEG)-electrolyte solution. Of 250 patients undergoing colonoscopy, 124 were randomized to receive 2 L PEG plus 15 mg of mosapride citrate (mosapride group), and 126 received 2 L PEG plus placebo (placebo group). Patients completed a questionnaire reporting the acceptability and tolerability of the bowel preparation process. The efficacy of bowel preparation was assessed by colonoscopists using a 5-point scale based on Aronchick’s criteria. The primary end point was optimal bowel preparation rates (scores of excellent/good/fair vs poor/inadequate).

RESULTS: A total of 249 patients were included in the analysis. In the mosapride group, optimal bowel preparation rates were significantly higher in the left colon compared with the placebo group (78.2% vs 65.6%, P < 0.05), but not in the right colon (76.5% vs 66.4%, P = 0.08). After excluding patients with severe constipation, there was a significant difference in bowel preparation in both the left and right colon (82.4% vs 66.7%, 80.8% vs 67.5%, P < 0.05, P < 0.01). The incidence of adverse events was similar in both groups. Among the subgroup who had previous colonoscopy experience, a significantly higher number of patients in the mosapride group felt that the current preparation was easier compared with patients in the placebo group (34/72 patients vs 24/74 patients, P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION: Mosapride citrate may be an effective and safe adjunct to PEG-electrolyte solution that leads to improved quality of bowel preparation, especially in patients without severe constipation.

Keywords: Mosapride citrate, Bowel preparation, Polyethylene glycol-electrolyte solution, Colonoscopy, Prokinetics

INTRODUCTION

Polyethylene glycol (PEG)-electrolyte solution is used worldwide for bowel cleansing. Approximately 2 L of this oral solution, along with a laxative, is usually required for adequate bowel preparation in Japan[1]. However, the need to drink such large volumes of liquid with an unpalatable taste has a negative impact on patient compliance[2]. A thorough bowel preparation is required for safe and effective colonoscopy, and inadequate preparation not only decreases the sensitivity, but also increases the difficulty of the procedure[3-5]. Therefore, more effective bowel preparation regimens for colonoscopy are required to improve the acceptability and tolerability of the procedure. Prokinetics such as domperidone, metoclopramide, and cisapride have been used in combination with PEG-electrolyte solution to improve the quality of bowel preparation[6-12]. However, the addition of prokinetic agents to PEG-electrolyte solution has not been proven to improve patient tolerance or colonic cleansing[10-12] and is sometimes associated with serious adverse effects. For example, domperidone and metoclopramide may cause extrapyramidal symptoms with long-term use[13]. Cisapride was withdrawn from the market because of severe cardiac side effects, including QT-interval prolongation and ventricular arrhythmias[14]. Thus, safer and more effective prokinetic agents are needed.

Mosapride citrate (mosapride) is a selective 5-hydroxytryptamine-4 (5-HT4) receptor agonist. Mosapride enhances gastric emptying and motility by facilitating acetylcholine release from the enteric cholinergic neurons, without blocking dopaminergic D2 receptors[15]. It is known to be effective in gastroesophageal reflex disease[16], functional gastrointestinal disorders, such as functional dyspepsia[17], chronic gastritis with delayed gastric emptying, and diabetic gastroparesis[18]. As 5-HT4 receptors are also located in the human colon and rectum[19,20], mosapride is also expected to have a prokinetic effect on the colo-rectum. A few clinical studies have reported that mosapride in combination with PEG may enhance bowel cleansing and improve patient acceptability and tolerability[21,22]. However, the efficacy and tolerability of a PEG-electrolyte solution with or without mosapride has not been studied in a double-blind, randomized trial.

We conducted this study to evaluate the efficacy, acceptability, and tolerability of mosapride as an adjuvant to PEG-electrolyte solution for colonoscopy preparation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a prospective, double-blind, randomized, controlled study that included patients who underwent colonoscopy at Aichi Cancer Center Hospital (ACCH), Nagoya, from January 2009 to October 2009. This study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of ACCH.

Study population

All consecutive outpatients aged 20-80 years who were scheduled for colonoscopy at ACCH were evaluated for study inclusion. Patients with the following clinical features were excluded: presence of significant cardiac, renal, hepatic, or metabolic comorbidities; presence of ascites or bowel obstruction; known allergy to PEG-electrolyte solution; history of gastric stapling or bypass procedure; or a history of prior colonic or rectal surgery. A gastroenterologist assessed patient eligibility, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to inclusion.

Randomization and blinding

Patients were randomly allocated to receive one of two bowel preparation regimens using a computer-generated random-number list. Patients were randomized in block sizes of two, with serially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. Concealed allocation was accomplished through non-research personnel who were not involved in this study. Comparisons between subjects who received 2 L PEG plus mosapride (mosapride group) and 2 L PEG plus placebo (placebo group) were made in a double-blind fashion.

Bowel preparation methods

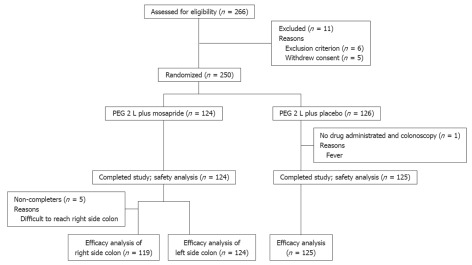

The colonoscopy preparation steps used in this study are shown in Figure 1. The day before colonoscopy, all patients were instructed to eat a pre-packaged, low-residue diet (Enimaclin CS; Horii Pharmaceutical Ind., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) that consisted of a lunch, snack, and dinner, and were asked to drink more than 2 L of clear liquid. On the day of the colonoscopy, all participants reported to the endoscopy room at 9:00 am, and received in-hospital bowel preparation. In-hospital preparation is important to ensure the uniformity of procedures within the study, and to remove any confounding caused by poor patient adherence. More than 10 toilet facilities were made available in the endoscopy unit for patient comfort. Six mosapride tablets (15 mg) (Gasmotin; Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) or six identical-looking placebo tablets were administered orally with water at 09:30. The timing of administration of the mosapride tablets was based on its pharmacokinetics[23]. After 30 min, both groups were instructed to drink 0.25 L of PEG-electrolyte solution (Niflec; Ajinomoto Pharmaceticals Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) every 15 min.

Figure 1.

Steps of preparation for colonoscopy.

Evaluation of bowel preparation

The efficacy of bowel preparation was assessed using Aronchick’s criteria[24], as follows: (1) Excellent (small volume of clear liquid, or greater than 95% of colonic surface seen); (2) Good (large volume of clear liquid covering 5% to 25% of colonic surface, but greater than 90% of surface seen); (3) Fair (some semisolid stool that could be suctioned or washed away, but greater than 90% of surface seen); (4) Poor (some semisolid stool that could not be suctioned or washed away, and less than 90% of surface seen); and (5) Inadequate (repeat preparation and colonoscopy needed). Participating endoscopists were trained to use Aronchick’s criteria to achieve a good level of agreement. Investigators performed calibration exercises involving more than 20 colonoscopies prior to study commencement, based on their interpretation of scale anchors, to ensure that their findings agreed. The final assessment of bowel preparation was divided into two categories: optimal and non-optimal. Bowel preparations rated as fair, good, or excellent, based on Aronchick’s criteria, were considered optimal; poor or inadequate ratings were considered non-optimal. After colonoscopy, two observers, including the endoscopist performing the procedure, determined the score by mutual agreement. They scored the quality of the preparation in the right colon (proximal to the splenic flexure), and the left colon (distal to the splenic flexure) and rectum separately. If the decision was discordant, a third expert reviewer graded and scored the recorded images, and this evaluation was used in the final analysis.

During or immediately following the colonoscopy, the investigator completed a physician questionnaire regarding the assessment of bowel preparation, amount of irrigation fluid used, time to reach the cecum, and ease of insertion into the cecum and visualization of the colonic lumen regardless of peristalses.

Patient tolerance and other measurements

The nursing staff recorded the time required to drink the indicated volume of lavage solution. They also recorded the time and number of motions from start of ingestion to the appearance of clear excretions. The nursing staff checked excretions until 1 h after patients finished the PEG + mosapride solution. If there was a solid stool with muddy excretions or no excretion at that time, we gave the patient an additional preparation, such as additional PEG or enema. A warm water enema of 500 mL volume was given until the excretions were clear. Patients who received an additional preparation were defined by Aronchick’s criteria as inadequate. The patient questionnaire, which was administered before bowel cleansing, consisted of 20 questions pertaining to patient characteristics, tolerability, and acceptability of study medication. It also included questions about the following: age; height; body weight; average number of bowel movements per week for the last year; number of previous colonoscopies; compliance with ingestion of PEG-electrolyte solution; willingness to repeat the same preparation regimen again, if required; ease/difficulty of taking the preparation compared with previous experiences; and presence of subjective symptoms while drinking PEG-electrolyte solution, such as nausea, vomiting, fullness, abdominal pain, and circulatory reactions such as palpitations or chest discomfort. We defined patients who suffered from constipation (defined as < 2 bowel movements per week) for > 1 year as having severe constipation. Patients completed the questionnaire before undergoing the colonoscopy and submitted the form to the nursing staff.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the difference in optimal rate of colon cleansing in the mosapride and placebo groups. Secondary endpoints included differences in patients’ acceptability and tolerance of solutions, time to first defecation, frequency of defecation, complete time for colonic preparation, time needed to reach the cecum, amount of irrigation fluid used, and subjective difficulty in colonoscopy insertion to the cecum and in observing the lumen of the colo-rectum because of peristalses.

Statistical analysis

The study was designed to detect an inter-group difference of 11% in the percentage of patients with optimal bowel preparation, with an α error of 5% and a power of 80%. This difference was based on a previous study[21]. The number of patients needed to demonstrate an 11% difference was 125 per treatment group, assuming a dropout rate of 10%.

The primary efficacy analysis was based on an intent-to-treat analysis and included patients who were randomized and received any treatment. The preparation of patients in this group was considered optimal or non-optimal based on the colonoscopist’s score regarding cleansing. Patients who did not undergo colonoscopy because of preparation-related adverse events, or preparation failure, or in whom the right colon could not be reached because of bowel obstruction or for technical reasons were excluded. The rates of optimal preparation were compared between the groups by the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

For secondary endpoints, the Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparison between continuous variables. Categorical variables were analyzed using the corrected χ2 or two-sided Fisher’s exact tests, where appropriate. The criterion for statistical significance was P < 0.05.

All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis Software (SPSS, version 12.0J for the PC, SPSS Japan, Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

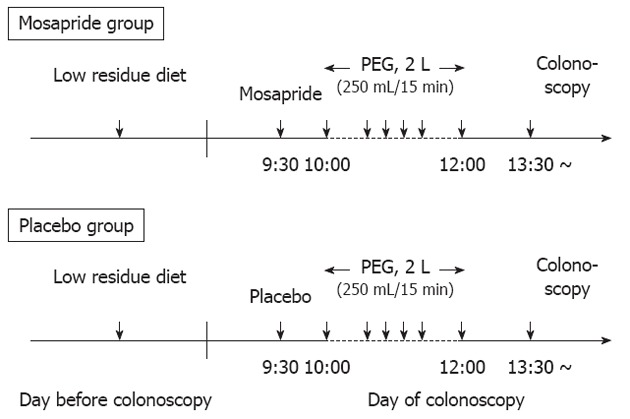

A total of 250 patients were randomized into two groups (Figure 2). Of those randomized to treatment, only one patient did not receive any treatment or undergo colonoscopy because he felt chilled and had a fever before treatment. Although 249 patients were analyzed, insertion of the colonoscope into the right colon failed in five (4%) patients in the mosapride group (advanced stenosing cancer in three and patient refusal in two), because of pain on colonoscopic advancement to the proximal colon. These five patients were excluded from the efficacy analysis of the right colon. Baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. Differences in age, gender, body mass index, and the number of previous colonoscopies between the mosapride and placebo groups were not significant. However, significantly more patients suffering from severe constipation (defined as < 2 bowel movements per week for > 1 year) were included in the mosapride group compared with the placebo group (P < 0.05). Therefore, we compared the efficacy, acceptability, and tolerability of the bowel preparation solution in subgroups of patients with or without severe constipation.

Figure 2.

Patient disposition flow chart. PEG: Polyethylene glycol.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Variable |

Overall |

Excluding patients with severe constipation |

P value |

|||

| A (mosapride) | B (placebo) | C (mosapride) | D (placebo) | A vs B | C vs D | |

| No. of patients | 124 | 125 | 108 | 120 | ||

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 67.3 ± 8.6 | 67.8 ± 10.1 | 67.3 ± 8.5 | 67.5 ± 10.2 | NS | NS |

| < 60 | 21 | 21 | 18 | 21 | NS | NS |

| 60-69 | 42 | 44 | 37 | 42 | ||

| ≥ 70 | 61 | 60 | 53 | 57 | ||

| Male | 69 | 83 | 64 | 80 | NS | NS |

| Female | 55 | 42 | 44 | 40 | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 22.5 ± 2.9 | 22.6 ± 2.7 | 22.7 ± 2.9 | 22.7 ± 2.6 | NS | NS |

| Bowel movements per week | ||||||

| < 2 | 16 | 5 | 0 | 0 | < 0.05 | NS |

| ≥ 2 | 108 | 120 | 108 | 120 | ||

| Previous colonoscopy | ||||||

| None (first time) | 38 | 27 | 32 | 26 | NS | NS |

| ≥ 2 | 86 | 98 | 76 | 94 | ||

P value by the χ2 test. NS: Not significant.

Bowel cleansing efficacy

As shown in Table 2, time to first defecation was significantly shorter in the mosapride group compared with the placebo group (P < 0.001). After excluding patients with severe constipation, the completion time for bowel preparation was significantly shorter in the mosapride group compared with the placebo group (P < 0.05). There were no differences in frequency of defecation, the elapsed time from last fluid intake to colonoscopy, time needed to reach the cecum, amount of irrigation fluid used, subjective difficulties in insertion to the cecum, and in observing the lumen of the colo-rectum between groups, or in the frequency of positive endoscopic findings.

Table 2.

Results of the preparation and endoscopic findings

| Variable |

Overall |

Excluding patients with severe constipation |

P value |

|||

| A (mosapride) | B (placebo) | C (mosapride) | D (placebo) | A vs B | C vs D | |

| No. of patients | 124 | 125 | 108 | 120 | ||

| Time to first defecation (min, mean ± SD) | 55.4 ± 27.3 | 71.2 ± 28.6 | 52.9 ± 26.2 | 70.4 ± 28.9 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Frequency of defecation (times, median, quartile) | 8.3 (4-18) | 8.6 (4-18) | 8.3 (4-18) | 8.0 (4-18) | NS | NS |

| Time of bowel preparation (min, mean ± SD) | 185.1 ± 63.8 | 198.0 ± 76.5 | 178.6 ± 58.2 | 198.0 ± 76.6 | 0.11 | < 0.05 |

| Elapsed time from last fluid intake to colonoscopy (min, mean ± SD) | 154.6 ± 48.9 | 154.1 ± 48.2 | 157.1 ± 63.2 | 155.5 ± 62.1 | NS | NS |

| Cecal intubation rate, n (%) | 119 (96.0) | 124 (99.2) | 108 (100) | 120 (100) | NS | NS |

| Insertion time1 (min, median, quartiles) | 7.8 (2-55) | 8.5 (2-38) | 7.4 (2-55) | 8.5 (2-38) | NS | NS |

| Feel of peristalsis, n (%) | 20 (16.1) | 22 (17.6) | 14 (13.0) | 22 (18.3) | NS | NS |

| Amount of irrigation fluid | ||||||

| None | 67 | 65 | 57 | 62 | NS | NS |

| < 50 mL | 40 | 47 | 33 | 46 | ||

| 50-100 mL | 15 | 11 | 12 | 11 | ||

| > 100 mL | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Endoscopic findings | ||||||

| Cancer | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | ||

| Polyps | 70 | 82 | 61 | 79 | NS | NS |

| Diverticulosis | 32 | 39 | 29 | 38 | ||

P value by the Mann-Whitney U test.

Insertion time was based on patients in whom the cecal portion of the colon examined. NS: Not significant.

The efficacy of bowel preparation is shown in Table 3. Twenty-five (20.2%) patients required additional preparation in the mosapride group (mean 0.6 L additional PEG in 22 patients, 0.5 L enema in one patient, and both in two patients). Thirty-eight (30.4%) patients required additional preparation in the placebo group (mean 0.75 L PEG in 35 patients, 0.5 L enema in one patient, and both in two patients).

Table 3.

Efficacy of overall colon-cleansing

| Variable |

Right colon |

Left colon and rectum |

P value |

|||

| Mosapride | Placebo | Mosapride | Placebo | Right | Left | |

| No. of patients | 119 | 125 | 124 | 125 | ||

| Overall score | ||||||

| Excellent | 39 | 24 | 48 | 33 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| Good | 34 | 38 | 37 | 39 | NS | NS |

| Fair | 18 | 21 | 12 | 10 | NS | NS |

| Poor | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | NS | NS |

| Inadequate | 25 | 39 | 25 | 39 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Optimal ratings, n (%) | 91 (76.5) | 83 (66.4) | 97 (78.2) | 82 (65.6) | 0.08 | < 0.05 |

P value by the χ2 test. NS: Not significant.

In the right colon, the number of bowel preparations rated as excellent was significantly higher in the mosapride group than in the placebo group (P < 0.05). However, the rate of optimal preparations did not differ significantly between groups (P = 0.08) (Table 3). After excluding patients with severe constipation, there were significant differences in the number of bowel preparations rated as excellent and the rate of optimal preparation in the mosapride group (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05 in the right colon and P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 in the left colon, respectively) (Table 4). In the left colon and rectum, the number of bowel preparations rated as excellent and the rate of optimal preparation were significantly higher in the mosapride group than in the placebo group (P < 0.05 and P < 0.05, respectively). These significant differences were maintained even after excluding patients with severe constipation (P < 0.05 and P < 0.05, respectively).

Table 4.

Results of colon-cleansing efficacy excluding patients with severe constipation

| Variable |

Right colon |

Left colon and rectum |

P value |

|||

| Mosapride | Placebo | Mosapride | Placebo | Right | Left | |

| No. of patients | 104 | 120 | 108 | 120 | ||

| Overall score | ||||||

| Excellent | 37 | 24 | 46 | 33 | < 0.01 | < 0.05 |

| Good | 31 | 37 | 33 | 38 | NS | NS |

| Fair | 16 | 20 | 10 | 9 | NS | NS |

| Poor | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | NS | NS |

| Inadequate | 18 | 36 | 18 | 36 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| Optimal ratings, n (%) | 84 (80.8) | 81 (67.5) | 89 (82.4) | 80 (66.7) | < 0.05 | < 0.01 |

P value by the χ2 test. NS: Not significant.

Patient tolerability and safety

There were no significant differences in compliance, as defined by > 80% and 100% intake of the PEG solution between the two groups (Table 5). Frequencies of symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, distention, abdominal pain, and circulatory reactions were similar in both groups. The proportion of patients who were willing to repeat the same preparation regimen was also similar in the two groups. However, among the subgroup of patients who had undergone a colonoscopy more than twice in the past, a significantly higher number of patients in the mosapride group felt that the current preparation was easier compared with patients in the placebo group (P < 0.05). This significant difference was maintained even after excluding patients with severe constipation (P < 0.05).

Table 5.

Results of patient questionnaire n (%)

| Variable |

Overall |

Excluding patients with severe constipation |

P value |

|||

| A (mosapride) | B (placebo) | C (mosapride) | D (placebo) | A vs B | C vs D | |

| No. of patients | 124 | 125 | 108 | 120 | ||

| Compliance > 80% | 120 (96.8) | 119 (95.2) | 105 (97.2) | 114 (95.0) | NS | NS |

| 100% intake | 112 (90.3) | 115 (92.0) | 97 (89.8) | 110 (91.7) | NS | NS |

| Any symptom | ||||||

| Nausea | 5 (4.0) | 6 (4.8) | 3 (2.7) | 4 (3.3) | NS | NS |

| Vomiting | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 | NS | NS |

| Distension | 40 (32.3) | 31 (24.8) | 31 (28.7) | 28 (23.3) | NS | NS |

| Abdominal pain | 4 (3.2) | 2 (1.6) | 3 (2.8) | 2 (1.7) | NS | NS |

| Circulatory reactions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS | NS |

| Willingness to repeat the same regimen | 77/115 (66.9) | 82/112 (73.2) | 67/100 (67.0) | 79/108 (73.1) | NS | NS |

| How easy/difficult to take preparation compared with previous one (easy/invariable/difficult) | 34/42/10 | 24/67/7 | 32/37/8 | 23/66/5 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 |

P value by the χ2 test. NS: Not significant.

DISCUSSION

This is the first prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy, acceptability, and tolerance of mosapride as an adjuvant to PEG-electrolyte solution for colonoscopy preparation. Mosapride is a benzisoxazole derivative prokinetic drug that is used for the treatment of gastrointestinal symptoms associated with chronic gastritis and functional dyspepsia[16,17,25-28]. It facilitates acetylcholine release from the enteric cholinergic neurons by its selective 5-HT4 receptor agonistic action[26]. It is also active through its main metabolite M1, which is a 5-HT3 agonist. The action of mosapride resembles that of a previously used 5-HT4 agonist, cisapride, which had been reported to be useful for bowel preparation[29,30]. Cisapride had additional effects of blocking K channels and D2 dopaminergic receptors and was withdrawn after its K channel blocking properties led to reports of QT interval prolongation and cardiac arrhythmias. In contrast to cisapride, mosapride does not block K channels or D2 dopaminergic receptors and is believed to have less cardiac toxicity[31].

5-HT4 receptors are present in the myenteric plexus and the muscle of stomach and colon, and mosapride has high affinity for these receptors[20,29,32]. In human studies, mosapride has been found effective for slow transit constipation, outlet obstruction-type constipation, constipation in Parkinson’s disease, and constipation associated with irritable bowel syndrome[33-35]. Recently, in guinea pigs, it was reported that mosapride enhanced the colon cleansing action of PEG via an increase in colonic transit, reducing not only fecal residue but also excessive fluid in the colonic lumen[36]. However, it is unclear whether mosapride would have additive beneficial effects on bowel cleansing before colonoscopy in humans.

We found that the rate of optimal preparation was significantly higher in the mosapride group compared with the placebo group in the left colon and rectum, but not in the right colon. The number of patients with bowel preparations rated as excellent was significantly higher for the mosapride group compared with the placebo group, especially for the right colon. Kim et al[37] have also described this differential efficacy of mosapride between the right and left colon in guinea pigs, and ascribed this finding to the differential distribution of colonic 5-HT4 receptors. Although the rates of optimal preparation were not significantly different in the right colon, the number of bowel preparations rated as excellent was significantly higher with the use of mosapride. Furthermore, after excluding patients with severe constipation, the rate of optimal preparation was significantly higher in the mosapride group compared with the placebo group. These findings support the efficacy of mosapride for bowel preparation.

In this study, many patients required additional bowel preparation. One possible reason may be that the nursing staff checked excretions 1 h after finishing the preparation, which may have been too short an interval for the PEG solution to adequately cleanse the colon. However, the rate of inadequate cleansing was significantly lower in the mosapride group compared with the placebo group. Furthermore, the time to first defecation was also significantly shorter in the mosapride group. The beneficial effect of mosapride on gastric emptying was expected to ameliorate nausea, vomiting, and fullness of the abdomen during bowel preparation. Mishima et al[22] showed that administration of mosapride prior to PEG solution significantly decreased the incidence of uncomfortable abdominal symptoms. However, there were no significant differences in the frequencies of these symptoms between the mosapride group and the placebo group in this study, and more patients were willing to repeat the same preparation regimen in the placebo group. This finding may be due to more abdominal distension and pain in the mosapride group due to its prokinetic effects. According to a postmarketing surveillance study, the most common adverse events associated with mosapride are abdominal pain and loose stools (both 0.35%)[38]. On the other hand, a larger proportion of patients in the mosapride group than in the placebo group felt that the preparation was easier to complete. These findings may support the efficacy of mosapride in terms of patient tolerance and acceptability. It is possible that 2 L of PEG solution is so large that these symptoms are unavoidable; in addition, it is also possible that the dose of mosapride was not sufficient to alleviate these symptoms.

Co-administration of laxatives such as sennoside and bisacodyl with lavage solution has been shown to improve colonic cleansing during colonoscopy. Addition of these adjunctive therapies has also allowed for lower volume PEG solutions to be administered with equivalent or increased efficacy. However, the adjunctive therapies have to be taken the day before the procedure. This may lead to sleep disturbances and inconvenience due to frequent defecation. If it is possible to begin the bowel preparation using mosapride on the same day as the colonoscopy, patient tolerability may improve.

Recently, it has been suggested that co-administration of mosapride and PEG-electrolyte solution is useful in preparing the colon for barium enema examination as it allows good evacuation of remaining feces[39]. As a result, mosapride is now approved in Japan for preparation for a barium enema examination, and a total dose of 40 mg mosapride is used. Major side effects have not been reported in Japan with this dose. In the present study, we administered 15 mg of mosapride for colonoscopy preparation, which is the recommended usual daily dosage of mosapride for adult patients with chronic gastritis. However because the effects of mosapride are reported to be dose-dependent[35,40], additional studies that address optimal dosage and timing of administration are required to clarify the best regimen for colonoscopy.

One of the limitations of this study was that there was a significant difference in the number of patients with severe constipation between the two groups. However, even with the inclusion of patients with severe constipation, there was a non-significant trend for improved preparation in the mosapride group, and this difference became significant after the exclusion of this subgroup. It is possible that for patients with severe constipation, the dose of 15 mg mosapride may be insufficient. The second limitation of this study was its single center location. Finally, we did not evaluate laboratory abnormalities, as co-administration of mosapride and PEG-electrolyte solution is already common in Japan for preparation for barium enema examination[39]. No serious laboratory abnormalities have been reported in Japan with a 40-mg dose of mosapride.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that co-administration of mosapride with PEG-electrolyte solution improves the quality of bowel preparation for colonoscopy in the left colon. Mosapride may be an effective and safe adjunct to PEG that leads to improved quality of bowel preparation, especially in patients without severe constipation.

COMMENTS

Background

Although prokinetics have been used in combination with polyethylene glycol (PEG)-electrolyte solution to improve patient acceptability and tolerance, as well as improve bowel cleansing, the efficacy and safety of these agents remain unproven. Prokinetics such as domperidone, metoclopramide, and cisapride have been used in combination with PEG-electrolyte solution to improve the quality of bowel preparation. However, the addition of prokinetic agents to PEG-electrolyte solution has not been proven to improve patient tolerance or colonic cleansing and can be sometimes associated with serious adverse effects. Thus, safer and more effective prokinetic agents are needed.

Research frontiers

Mosapride citrate (mosapride) is a selective 5-hydroxytryptamine-4 (5-HT4) receptor agonist. Mosapride enhances gastric emptying and motility by facilitating acetylcholine release from the enteric cholinergic neurons, without blocking dopaminergic D2 receptors. It is known to be effective in gastroesophageal reflex disease, functional gastrointestinal disorders, such as functional dyspepsia, chronic gastritis with delayed gastric emptying, and diabetic gastroparesis. As 5-HT4 receptors are also located in the human colon and rectum, mosapride is also expected to have a prokinetic effect on the colo-rectum. A few clinical studies have reported that mosapride in combination with PEG may enhance bowel cleansing and improve patient acceptability and tolerability.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This is the first prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy, acceptability, and tolerance of mosapride as an adjuvant in PEG-electrolyte solution for colonoscopy preparation. This study demonstrated that co-administration of mosapride with PEG-electrolyte solution improves the quality of bowel preparation for colonoscopy in the left colon.

Applications

The study results suggest that mosapride may be an effective and safe adjunct to PEG, leading to an improved quality of bowel preparation, especially in patients without severe constipation. Additional studies that address optimal dosage and timing of administration are required to clarify the best bowel preparation method for colonoscopy.

Terminology

PEG-electrolyte solution: PEG-electrolyte solution is used worldwide for bowel cleansing. Approximately 2 L of this oral solution with some laxatives is usually required for adequate bowel preparation in Japan. However, the need to drink such large volumes of liquid with an unpalatable taste has a negative impact on patient compliance.

Peer review

This is an interesting and well written study. The methodology and evaluation of data is correct. The conclusion sounds good and useful for the general practice.

Footnotes

Peer reviewers: Vito Annese, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Surgical and Medical Sciences, Unit of Gastroenterology, University Hospital Careggi, Pad. S. Luca Nuovo 16c, Largo Brambilla, 3, 50134 Florence, Italy; Luis Bujanda, PhD, Professor, Departament of Gastroenterology, CIBEREHD, University of Country Basque, Donostia Hospital, Paseo Dr. Beguiristain s/n, 20014 San Sebastián, Spain; Dr. Mitsuhiro Fujishiro, Department of Gastroenterology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8655, Japan

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Iida Y, Miura S, Asada Y, Fukuoka K, Toya D, Tanaka N, Fujisawa M. Bowel preparation for the total colonoscopy by 2,000 ml of balanced lavage solution (Golytely) and sennoside. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1992;27:728–733. doi: 10.1007/BF02806525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harewood GC, Wiersema MJ, Melton LJ. A prospective, controlled assessment of factors influencing acceptance of screening colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:3186–3194. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Regula J, Rupinski M, Kraszewska E, Polkowski M, Pachlewski J, Orlowska J, Nowacki MP, Butruk E. Colonoscopy in colorectal-cancer screening for detection of advanced neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1863–1872. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wexner SD, Beck DE, Baron TH, Fanelli RD, Hyman N, Shen B, Wasco KE. A consensus document on bowel preparation before colonoscopy: prepared by a task force from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:894–909. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.03.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ness RM, Manam R, Hoen H, Chalasani N. Predictors of inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1797–1802. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ziegenhagen DJ, Zehnter E, Tacke W, Gheorghiu T, Kruis W. Senna vs. bisacodyl in addition to Golytely lavage for colonoscopy preparation--a prospective randomized trial. Z Gastroenterol. 1992;30:17–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazarczyk DA, Stein AD, Courval JM, Desai D. Controlled study of cisapride-assisted lavage preparatory to colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:44–48. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reiser JR, Rosman AS, Rajendran SK, Berner JS, Korsten MA. The effects of cisapride on the quality and tolerance of colonic lavage: a double-blind randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:481–484. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)80007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katsinelos P, Pilpilidis I, Paroutoglou G, Xiarchos P, Tsolkas P, Papagiannis A, Giouleme O, Kapelidis P, Papageorgiou A, Dimiropoulos S, et al. The administration of cisapride as an adjuvant to PEG-electrolyte solution for colonic cleansing: a double-blind randomized study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:441–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martínek J, Hess J, Delarive J, Jornod P, Blum A, Pantoflickova D, Fischer M, Dorta G. Cisapride does not improve precolonoscopy bowel preparation with either sodium phosphate or polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:180–185. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.116562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brady CE, DiPalma JA, Pierson WP. Golytely lavage--is metoclopramide necessary? Am J Gastroenterol. 1985;80:180–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhodes JB, Engstrom J, Stone KF. Metoclopramide reduces the distress associated with colon cleansing by an oral electrolyte overload. Gastrointest Endosc. 1978;24:162–163. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(78)73495-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brogden RN, Carmine AA, Heel RC, Speight TM, Avery GS. Domperidone. A review of its pharmacological activity, pharmacokinetics and therapeutic efficacy in the symptomatic treatment of chronic dyspepsia and as an antiemetic. Drugs. 1982;24:360–400. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198224050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tonini M, De Ponti F, Di Nucci A, Crema F. Review article: cardiac adverse effects of gastrointestinal prokinetics. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1585–1591. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshida N, Omoya H, Oka M, Furukawa K, Ito T, Karasawa T. AS-4370, a novel gastrokinetic agent free of dopamine D2 receptor antagonist properties. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1989;300:51–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruth M, Finizia C, Cange L, Lundell L. The effect of mosapride on oesophageal motor function and acid reflux in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:1115–1121. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200310000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mizuta Y, Shikuwa S, Isomoto H, Mishima R, Akazawa Y, Masuda J, Omagari K, Takeshima F, Kohno S. Recent insights into digestive motility in functional dyspepsia. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1025–1040. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1966-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asakawa H, Hayashi I, Fukui T, Tokunaga K. Effect of mosapride on glycemic control and gastric emptying in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with gastropathy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2003;61:175–182. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(03)00121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLean PG, Coupar IM. Stimulation of cyclic AMP formation in the circular smooth muscle of human colon by activation of 5-HT4-like receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;117:238–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakurai-Yamashita Y, Yamashita K, Kanematsu T, Taniyama K. Localization of the 5-HT(4) receptor in the human and the guinea pig colon. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;383:281–285. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00642-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagashima M, Okamura S, Iizuka H, Ohmae Y, Sagawa T, Kudo T, Masuo T, Kobayashi R, Marubashi K, Ishikawa T, et al. Mosapride citrate for colonoscopy preparation with lavage. Kitakanto Med J. 2002;52:111–115. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mishima Y, Amano Y, Okita K, Takahashi Y, Moriyama N, Ishimura N, Furuta K, Ishihara S, Adachi K, Kinoshita Y. Efficacy of prokinetic agents in improving bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Digestion. 2008;77:166–172. doi: 10.1159/000141040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakashita M, Yamaguchi T, Miyazaki H, Sekine Y, Nomiyama T, Tanaka S, Miwa T, Harasawa S. Pharmacokinetics of the gastrokinetic agent mosapride citrate after single and multiple oral administrations in healthy subjects. Arzneimittelforschung. 1993;43:867–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aronchick CA, Lipshutz WH, Wright SH, Dufrayne F, Bergman G. A novel tableted purgative for colonoscopic preparation: efficacy and safety comparisons with Colyte and Fleet Phospho-Soda. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:346–352. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.108480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hunt RH, Tougas G. Evolving concepts in functional gastrointestinal disorders: promising directions for novel pharmaceutical treatments. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;16:869–883. doi: 10.1053/bega.2002.0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshida N, Kato S, Ito T. Mosapride Citrate. Drugs Future. 1993;18:513–515. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hongo M. Initial approach and pharmacotherapy for functional dyspepsia-a large clinical trial in Japan. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:A–506. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanaizumi T, Nakano H, Matsui Y, Ishikawa H, Shimizu R, Park S, Kuriya N. Prokinetic effect of AS-4370 on gastric emptying in healthy adults. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;41:335–337. doi: 10.1007/BF00314963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inui A, Yoshikawa T, Nagai R, Yoshida N, Ito T. Effects of mosapride citrate, a 5-HT4 receptor agonist, on colonic motility in conscious guinea pigs. Jpn J Pharmacol. 2002;90:313–320. doi: 10.1254/jjp.90.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jost WH, Schimrigk K. Long-term results with cisapride in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 1997;12:423–425. doi: 10.1002/mds.870120324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kii Y, Nakatsuji K, Nose I, Yabuuchi M, Mizuki Y, Ito T. Effects of 5-HT(4) receptor agonists, cisapride and mosapride citrate on electrocardiogram in anaesthetized rats and guinea-pigs and conscious cats. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;89:96–103. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2001.d01-142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taniyama K, Makimoto N, Furuichi A, Sakurai-Yamashita Y, Nagase Y, Kaibara M, Kanematsu T. Functions of peripheral 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors, especially 5-hydroxytryptamine4 receptor, in gastrointestinal motility. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:575–582. doi: 10.1007/s005350070056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Odaka T, Suzuki T, Seza A, Yamaguchi T, Saisho H. [Serotonin 5- HT4 receptor agonist (mosapride citrate)] Nihon Rinsho. 2006;64:1491–1494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Z, Sakakibara R, Odaka T, Uchiyama T, Uchiyama T, Yamamoto T, Ito T, Asahina M, Yamaguchi K, Yamaguchi T, et al. Mosapride citrate, a novel 5-HT4 agonist and partial 5-HT3 antagonist, ameliorates constipation in parkinsonian patients. Mov Disord. 2005;20:680–686. doi: 10.1002/mds.20387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimatani H, Kojima Y, Kadowaki M, Nakagawa T, Fujii H, Nakajima Y, Takaki M. A 5-HT4 agonist mosapride enhances rectorectal and rectoanal reflexes in guinea pigs. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;285:G389–G395. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00085.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mine Y, Morikage K, Oku S, Yoshikawa T, Shimizu I, Yoshida N. Effect of mosapride citrate hydrate on the colon cleansing action of polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution (PEG-ELS) in guinea pigs. J Pharmacol Sci. 2009;110:415–423. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08331fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim HS, Choi EJ, Park H. The effect of mosapride citrate on proximal and distal colonic motor function in the guinea-pig in vitro. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:169–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oikawa T, Takemoto Y, Haramu K. Post-marketing surveillance of mosapride citrate (Gasmotin) in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia on long-term administration [in Japanese] Rinsho Iyaku. 2005;21:831–837. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Futei S, Sugino Y, Kuribayashi S, Imai Y, Ueno F, Hibi T, Mitsushima T. [New preparation method for barium enema: efficacy and administration of oral intestinal lavage solution with gastrointestinal prokinetic agent] Nihon Igaku Hoshasen Gakkai Zasshi. 2004;64:22–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miyoshi A, Miwa T, Harasawa S, Yoshida Y, Masamune O, Kimura K, Niwa H, Mori H, Asakura H, Hayakawa T, et al. Dose-finding study of AS-4370 (mosapride citrate) in patients with chronic gastritis [in Japanese] Rinsho Iyaku. 1998;14:1069–1090. [Google Scholar]