Abstract

Etomidate is a hydrophobic molecule, a potent general anesthetic, and the best understood drug in this group. Etomidate’s target molecules are GABAA receptors, its site of action has been identified with photolabeling, and a quantitative allosteric co-agonist model has emerged for etomidate effects on GABAA receptors. We have shown that when methionine residues that are thought to be adjacent to the etomidate site are mutated to tryptophan, that the bulky hydrophobic side-chains alter mutant GABAA receptor function in ways that mimic the effects of etomidate binding to wild-type receptors. Furthermore, these mutations reduce receptor modulation by etomidate. Both of these observations support the hypothesis that these methionine residues form part of the etomidate binding pocket.

Keywords: GABA-A Receptor, Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor, Ion Channel, Allosteric Model, Etomidate, General Anesthesia, Site-directed Mutagenesis, Electrophysiology

1. Introduction

The potent general anesthetic etomidate, acts via ionotropic γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors containing β2 and β3 subunits to produce sedation, loss-of-righting reflexes, and immobilization in the presence of noxious stimuli (Jurd et al., 2003; Reynolds et al., 2003). GABAA receptors are ligand-gated chloride channels formed from five subunits arranged around a central transmembrane pore. Etomidate acts as a positive allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors, enhancing chloride channel activation in the presence of low GABA concentrations, lowering GABA EC50, and prolonging inhibitory post-synaptic currents in the brain (Hill-Venning et al., 1997; Yang and Uchida, 1996; Zhong et al., 2008). High concentrations of etomidate also directly activate (i.e. agonize) GABAA receptors in the absence of GABA (Hill-Venning et al., 1997; Yang and Uchida, 1996). Using quantitative electrophysiology in Xenopus oocytes expressing α1β2γ2L GABAA receptors with stoichiometry 2α:2β:1γ (Chang et al., 1996), we found that both GABA potentiation and direct activation by etomidate are consistent with a single class of allosteric agonist sites (Rüsch et al., 2004). Our functional analysis suggested that two equivalent etomidate sites best explained the results. Subsequently, a radiolabeled photoreactive etomidate analog, azi-etomidate, was synthesized (Husain et al., 2003) and used to identify etomidate binding residues in purified bovine GABAA receptors (Li et al., 2006). The two photo-modified residues that accounted for nearly all the incorporated radioactivity were conserved methionines in transmembrane domains, one on α subunits (αM236), and one on β subunits (βM286). Azi-etomidate photo-incorporation at both αM236 and βM286 is inhibited in parallel by etomidate, suggesting that these residues both contribute to a single class of binding sites. Structural studies of GABAA receptors confirm that these methionines are located at the transmembrane interface where α and β subunits abut (Bali et al., 2009) and that two such interfacial sites are present on each receptor-channel complex.

For the experiments described here, we hypothesized that because etomidate is a bulky hydrophobic molecule,, mutating the photolabeled methionines to bulky hydrophobic tryptophans would mimic the presence of etomidate in its binding pocket. We created expression plasmids encoding α1M236W and β2M286W mutant subunits, co-expressed these in Xenopus oocytes with other wild-type subunits to produce α1M236Wβ2γ2L and α1β2M286Wγ2L receptors, and characterized their gating behavior and sensitivity to both GABA and etomidate (Stewart et al., 2008). Gating behavior have been quantified under multiple conditions: 1) basal gating in the absence of ligands; 2) GABA-dependent gating; 3) maximal GABA efficacy; 4) etomidate direct activation and efficacy; and 5) etomidate modulation of GABA sensitivity (left-shift or EC50 ratio). Our results demonstrated that tryptophan mutations at these two residues produce channels with enhanced sensitivity to GABA and spontaneous gating activity, changes that mimic the GABA-potentiating and direct activating effects of etomidate. In addition, left-shift analysis showed that, compared to wild-type, the mutant receptors are far less sensitive to etomidate, possibly because they partially occupy the space where etomidate normally binds.

Here, we describe the methods for Xenopus oocyte channel expression and electrophysiology, detail the procedures used to quantify each of the functional characteristics of GABAA receptors, and the quantitative analysis and model-fitting procedures.

2. Materials

2.1. Site-directed mutagenesis and messenger RNA synthesis

Plasmids encoding human α1, β2, and γ2L GABAA receptor subunits. Cloning vectors must have properly oriented transcription initiation sites for in vitro synthesis of mRNA. We subcloned cDNAs into pCDNA3.1 vectors (Invitrogen), which include a T7 transcription site and a BGH polyadenylation sequence that is important for stability of mRNA transcripts.

Quick-Change mutagenesis kit (Stratagene).

- Oligonucleotides for mutagenesis (see note 1). The oligonucleotide sequence used for the Quick-change mutagenesis were:

- α1M236W:TATTCAAACATACCTGCCGTGCATATGGACAGTTATTCTCTCCCAAGTCTCAT

- β2M286W: TGAAGGCCATTGACATGTACCTGTGGGGGTGCTTTGTCTTCGTTTTCATG

DNA Miniprep kits (Qiagen).

DNA purification kits: Wizard SV Gel and PCR Cleanup (Promega Corporation).

Endonuclease enzymes and buffers for linearization (New England Biolabs).

Agarose Gel Electrophoresis (minigel) equipment.

DNA Sequencing facility. 9. mMessage Machine and mRNA Purification kits (Ambion/Applied Biosystems).

2.2 Xenopus oocyte harvest, injection, and culture

Frogs. Adult female Xenopus laevis, injected with hcg, were purchased from Xenopus One. They are housed in a veterinary-supervised temperature-controlled environment with 12-hour light/dark cycles.

Calcium-free OR2 (82 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.6) and ND96 (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.6) supplemented with Gentamicin 50 μg/ml (see note 2).

Tricaine (Ethyl 3-aminobenzoate methanesulfonate salt) is purchased from Sigma Aldrich.

Fine forceps (Dumont #4 or #5 from Fine Science Tools).

Standard forceps (Dumont #2 or #3 from Fine Science Tools).

Collagenase Type 2 (Worthington Biochemical) solution (1 mg/ml in OR2).

Plastic-ware: Cell-culture dishes (10 cm and 15 cm diameter); Centrifuge tubes (15 and 50 ml); Disposable plastic transfer pipettes; Dispolable small plastic culture loops.

Dissecting microscope and illuminator.

Manual 3D micromanipulator with pipette holder (World Precision Instruments; see note 3).

Micropipettes for injection (10 μL).

Microinjector (Drummond Digital Microdispenser).

Cell-culture dish (5 cm) with plastic mesh (or Velcro) insert. The plastic mesh insert, cut to fit snuggly in the bottom of the cell-culture dish, provides a grid of appropriately sized holes (about 0.5 mm square) to keep the oocytes from rolling during injection.

Mineral oil.

Messenger RNA mixtures in RNAase-free water.

2.3 Oocyte electrophysiology (see note 4)

Vibration damping and faraday cage. While commercial tabletop vibration-damping devices are available, we achieve adequate damping using a heavy iron plate (12″ × 16″ × 0.75″) mounted on four large rubber stoppers. A faraday cage adequate for these experiments can be built from conductive metal screening on a frame (copper is ideal; aluminum is adequate).

Dissecting microscope and fiberoptic illuminator. (both from World Precisions Instruments).

Multi-reservoir remote-controllable superfusion system (ALA Scientific Instruments).

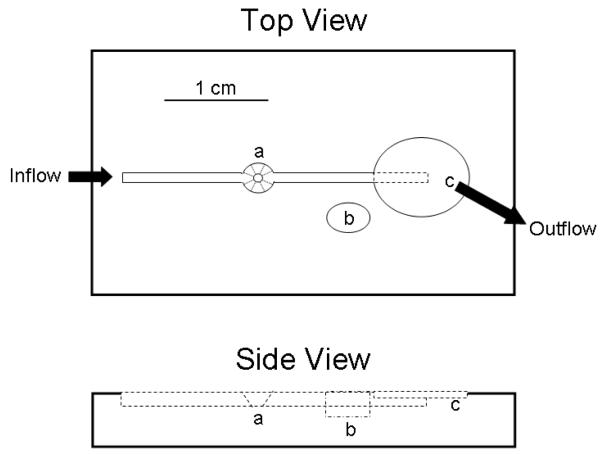

Low-volume flow chamber. Figure 1 depicts a simple linear flow cell with a low-volume chamber for an oocyte, a guard chamber for use of a salt-bridge, and a depressed “drain” area where outflow solution is removed into a suction canister using a house vacuum or peristaltic pump.

Two microelectrode voltage clamps (Warner Instruments).

Micromanipulators for electrodes.

Digitizer and data collection software: Digidata 1440 digitizer interface and pClamp software, both from Molecular Devices.

Microelectrodes (borosilicate pipettes and pipette puller; see note 5).

3M KCl for microelectrodes.

Bleach for treating Ag/AgCl2 electrodes.

GABA (Sigma-Aldrich) stock solution: 1 mM in ND96.

Picrotoxin (Sigma-Aldrich): 2 mM in ND96.

Etomidate (Bedford Laboratories): clinical preparation is 2 mg/ml (8.2 mM) in 35% (v/v) propylene glycol.

Alphaxalone (MP Biomedical): 2 mM in DMSO.

Figure 1. Diagram of a simple flow-cell design for oocyte electrophysiology.

The inflow channel is sized to accommodate small PTFE tubing (OD 0.12″). The oocyte chamber (a) is beveled to allow microelectrodes to enter at an angle from either side of the flow channel. The guard chamber (b) enables use of a salt bridge to reduce grounding variability. The outflow incorporates a stepped chamber design that allows suction to remove excess superfusate without removing all the fluid in the flow channel if inflow stops.

2.4 Data analyses

Clampfit 9.0 software (Molecular Devices)

Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc.)

Origin 6.0 software (OriginLab Corp.)

3. Methods

3.1. Site-directed mutagenesis and messenger RNA synthesis

1. Perform site-directed mutagenesis with appropriate template and mutagenic oligonucleotides.

2. Confirm sequence. We sequence the entire cDNA region with a set of sequencing oligonucleotides.

3. Linearize DNAs: Plasmids containing alpha and gamma GABA receptor wild type and mutant cDNAs were linearized with Xma I, and beta cDNAs were cut with Stu I. Linearized DNA is visualized on 0.8% agarose gel, and extracted from excised gel regions with Wizard clean-up kits.

5. mRNAs were synthesized using the mMessage mMachine T7 kit and were purified using NucAway Spin Columns (both from Ambion). mRNA yields were quantified using A260 measurements.

6. mRNAs were mixed for injection at a ratio of 1 alpha: 1 beta: 2-5 gamma subunit at a total RNA concentration of 0.2 μg/μl using Nuclease-free water (Ambion).

7. DNAs and mRNAs were visualized on 1% agarose gels using ethidium bromide and documented using a digital camera.

3.2 Xenopus Oocyte harvest, injection, and culture

Prior to mini-laparotomy (0.5 cm incision) to extract oocytes, frogs are anesthetized by immersion in ice cold 1.5% tricaine, pH 7.0. We prepare this solution using 1 litre of deionized water in a styrofoam ice bucket fitted with a cover.

Adequate anesthesia is assessed by both handling the frogs and pinching their abdomens and limbs with forceps prior to surgery. Modified aseptic technique is used in accordance with recent ARAC guidelines (http://oacu.od.nih.gov/ARAC/XenopusOocyte_101007_Fnl.pdf). Instruments are sterilized with heat or alcohol and flame, but no antiseptic prep is used on frog skin, which secretes peptides with broad antibiotic activity.

The abdominal skin is retracted using fine forceps or the tip of a sterile 19 gauge needle and a 0.5 cm incision is made in skin only using small sharp scissors (heat sterilized). The abdominal wall is then held with heavy forceps and punctured using the 19 gauge needle. The abdominal opening through muscle and fascia is enlarged by inserting the tips of the small scissors and opening them in a roughly cephalad-to-caudad direction (parallel to the muscle fibers). The heavy forceps are inserted into the wound and used to gently retract a lobe of ovary (see note 6). The lobe (volume approximately 1-2 ml) is excised with sharp scissors and placed in OR2 solution in a 10 cm diameter plastic cell-culture dish. The remaining ovary is pushed back into the abdominal cavity. The wound is closed in two layers (muscle/fascia first, then skin) with resorbable suture (3.0 or 4.0 Vicryl), using simple or figure-of-eight stitches.

Following surgery, frogs are recovered in room temperature shallow deionized water, oriented to keep their snouts above water. It is important to keep a heavy lid on the recovery chamber, to keep the frogs from jumping out and running for cover in the lab (they prefer the dark areas under equipment). Frogs are returned to the animal care facility following 1-2 hours of recovery, when they display vigorous activity.

Using one pair of heavy forceps and one pair of fine forceps, the excised portion of ovary is gently torn into small pieces, each containing four to ten oocytes (see note 7).

Transfer the small portions of ovary from the culture dish to 15 ml centrifuge tubes, approximately 1 ml of oocytes per tube, each containing 5 ml OR2 (see note 8). The ovaries will sink to the bottom of the tube. Gently aspirate the OR2 above the oocytes, and wash the oocytes by gently agitating with additional 5 ml aliquots of OR2 until clear. 7. Add 5 ml of Collagenase solution to each centrifuge tube. Place on a rocking platform or gentle orbital shaker, and incubate for 1 hour at room temperature (22 °C).

After 1 hour, aspirate collagenase solution from above the oocytes, and replace with fresh collagenase solution. Incubate for an additional 30-60 minutes (see note 9)

When oocytes are mostly free of connective tissue, aspirate collagenase solution and wash six times with 5 ml aliquots of OR2, gently agitating, then aspirating after each rinse. Resuspend oocytes in ND96 supplemented with antibiotics, and transfer to a 15 cm diameter cell-culture dish filled to a 3-4 mm depth with ND96 supplemented with antibiotics. While transferring, arrange the oocytes in a line across the diameter of the dish.

Examine the oocytes under a dissecting microscope. Identify healthy-appearing stage V and VI oocytes (these have a distinct band between the dark and light poles), and using a small plastic culture loop, separate these oocytes to another part of the culture dish, then use a disposable pasteur pipette to transfer them to a small culture dish containing ND96 supplemented with antibiotics. These oocytes will be used for injection. The remaining oocytes can be discarded or maintained in culture, in ND96 plus antibiotics at 17 °C for several days.

Prepare mRNA mixtures for injection in nuclease-free water. We usually use mRNA concentrations of 0.2 -0.5 ng/nl and w/w ratios of 1α:1β:2-5γ to improve incorporation of γ subunits into receptors (Boileau et al., 2002). These mixtures are stored at -80 °C and kept on ice during use.

Injection pipettes are pulled to a sharp tapered needle and broken to a sharp bevel on a glass bead on the microforge (see note 10). A small amount of mineral oil is inserted into the back end of the injection pipette, leaving no air space, and the pipette is carefully slid onto the plunger needle of the microinjector. After sealing the pipette onto the microinjector with the locking nut/flange, the plunger is advanced until a small droplet of oil is expressed at the tip. The microinjector is then mounted on the micromanipulator. A small depression is created in a piece of parafilm using a disposable pipette tip and a 2 μl droplet of mRNA mixture is deposited in the depression--it should appear clear with no particulate matter in it. Under the microscope, the injection pipette tip is positioned so that the tip is aiming at the center of this droplet, then advanced until the tip is in the droplet. Slowly draw the mRNA into the injection pipette by withdrawing the plunger, making sure that the solution is flowing, and that no air bubbles enter the injection pipette. When all of the solution is loaded into the injection pipette, retract the entire injector to keep the tip from being damaged while setting up oocytes for injection.

Transfer about 10-20 oocytes in ND96 plus antibiotics to the cell-culture dish fitted with a circle of plastic screen on its base. Arrange the oocytes in a line with their dark sides or the equatorial bands oriented toward the injection pipette. Advance the pipette until the tip enters the ND96 and is near the oocytes. Under microscope guidance, advance the pipette tip until it touches the first oocyte. Continue advancing until the pipette tip enters the oocyte. Slowly inject 25-50 nl (this is only a fraction of a turn on the Drummond injector) while observing the oocyte. It should visibly “plump up” as the injection occurs. Wait 5-10 seconds and withdraw the pipette tip to a position above the oocytes. Manually move the cell-culture dish until the next oocyte is positioned below the injector and continue injecting until all the oocytes are injected.

Transfer injected oocytes into labeled cell-culture trays in ND96 supplemented with gentamicin. Incubate at 17 °C for 24-96 hr. Examine daily for unhealthy oocytes (bloated with pale opalescent membranes) and remove these. Change ND96 solution daily.

3.3 Oocyte Electrophysiology

1. GABA concentration-response

Starting with a fresh aliquot of 1M GABA stock solution (see note 11), prepare a range of ND96 (antibiotic-free) superfusion solutions with GABA concentrations ranging from 0.1μM to 1 mM. We typically use half-log (3.2-fold) concentration steps. Concentration-responses should include at least 6 concentrations: one or two producing less than 10% activation, two or three defining the steep rising portion of the response curve, and at least two defining the maximal plateau. Recordings are performed at room temperature with oocytes clamped at -50 mV. Software-controlled experiments typically record 5-10 s of baseline data (ND96 solution) before switching superfusate to a GABA solution for 20-60 s, and then returning to ND96 for 20-30 s. The time required to reach peak current depends on the GABA concentration and flow characteristics in the chamber holding the oocyte. After each sweep, oocytes are “washed” in ND96 for at least 3 minutes before the subsequent experiment. This wash time is needed to allow desensitized receptors to return to activatable states (the current should return to a value similar to baseline current prior to GABA application), and is longer after long exposures to high GABA concentrations (Chang et al., 2002). To facilitate normalization of responses at different GABA concentrations, we measure a standard response every 2nd or 3rd sweep (see note 12).

2. Spontaneous channel activation

To assess whether spontaneously active GABAA receptors are present in the absence of agonists, we apply picrotoxin (see note 13), a potent inhibitor, and determine whether the “leak” current observed during superfusion with ND96 alone can be reduced. Data from Chang & Weiss (Chang and Weiss, 1999) suggest that, in comparison to wild-type, spontaneously active mutant GABAA receptors may be less sensitive to picrotoxin. We therefore use a high (2 mM) concentration of picrotoxin. The picrotoxin current (IPTX) must be normalized to maximal GABA responses () measured before and after the picrotoxin experiment. It is important to note that spontaneously active channels are often extremely sensitive to even nanomolar concentrations of GABA, so we make sure that the tubing and valves used for picrotoxin experiments are entirely GABA-free. In some cases, we have used “virgin” tubing and valves and manually apply picrotoxin, in order to avoid GABA contamination in these experiments.

Wild-type GABAA receptors have no detectable spontaneous activation (see note 14). In mutants where no spontaneous activity is detectable using picrotoxin, we have used known gating mutations and mutant-cycle analysis to estimate the mutant effect on spontaneous gating (Desai et al., 2009).

3. Maximal GABA efficacy

We use positive allosteric modulators to detect whether the maximal current response to GABA alone can be enhanced. In wild-type receptors, we have used 3 μM etomidate or 2 μM alphaxalone as allosteric enhancers. In channels with mutations that create etomidate insensitivity (such as α1M236W and β2M286W), we have found that alphaxalone retains strong enhancing activity (see note 15). The experiment is performed as a single sweep with three superfusate solutions; a baseline period in ND96; a period in maximally activating GABA until desensitization begins, then a period in maximal GABA plus enhancing compound. If the open probability at maximal GABA () is significantly less than 1.0, addition of enhancer (i.e. IGABA+Alphax) will open channels that are closed.

4. Etomidate direct activation

Etomidate concentration-response data is obtained similarly to GABA concentration responses. Our etomidate (FW = 244 g/mole) stock is the clinical preparation at 2 mg/ml (8.2 mM) in 35 volume % propylene glycol. We use concentrations up to 1 mM in experiments (see note 16) and have shown that the resulting propylene glycol concentration does not affect GABAA receptors. Etomidate is extremely hydrophobic and binds nonspecifically to lipids and proteins in the oocyte cytoplasm (see note 17). As a result, washout of etomidate can be extremely slow, requiring wash periods of up to 15 minutes between exposures (longer with higher etomidate concentrations). As with other experiments, normalization sweeps establishing maximal GABA responses are intermittently performed along with the etomidate responses.

5. Etomidate modulation of GABA responses (left-shift)

To measure the GABA-enhancing activity of etomidate, we use left-shift analysis. This simply compares the ratios of GABA EC50 in the absence of etomidate to GABA EC50s when etomidate is present. At least one etomidate concentration should be assessed this way. We chose a low concentration (3.2 μM) that is clinically relevant and produces large shifts in wild-type GABA sensitivity. Because control GABA EC50 can vary significantly from oocyte to oocyte, we prefer to measure left-shift by performing both control and etomidate-shifted GABA concentration-responses in individual oocytes, generating an EC50 ratio for each cell studied. Control GABA concentration-responses are measured as described above (section 3.3.1). We then repeat the GABA concentration response, using three-solution sweeps where oocytes are pre-exposed to 3.2 μM etomidate in ND96 for 30 s, then to solutions that contain both variable GABA and 3.2 μM etomidate (see note 18). Normalization sweeps establishing maximal GABA responses are intermittently performed along with the GABA concentration-responses.

3.4 Data Analyses

We have evaluated our data using a two-state equilibrium Monod-Wyman-Changeux (MWC) co-agonist model. Although this mechanism oversimplifies the number of states accessible to GABAA receptors (for instance, we ignore desensitized states), it provides a remarkably good quantitative fit as well as a useful framework for interpretation of results (Desai et al., 2009; Rüsch et al., 2004; Stewart et al., 2008). This model assumes that an equilibrium between inactive and active protein conformations is present in the absence of agonists or modulating ligands. This lower boundary of receptor activity is estimated using experiments described in Section 3.3.2. The theoretical upper bound of activation (100%) is assumed to be approximated when maximal GABA is enhanced with the positive allosteric modulator, alphaxalone. The efficacies of GABA (Section 3.3.3), etomidate (Section 3.3.4) and the combination of GABA plus etomidate can be estimated by comparison with the maximal GABA + alphaxalone response.

1. Leak correction

We use Clampfit 9.0 for leak correction (see note 19). The software has a function that allows identification of a baseline region between two cursors, and then corrects the entire sweep by subtracting the average current between the two cursors. A third cursor is positioned at the peak response, which is recorded along with the activating ligand concentrations.

2. Agonist concentration-response analysis

For either GABA or etomidate activation, descriptive analysis is performed using non-linear least squares regression fits to logistic functions (Equation 1):

| (1) |

Normalized concentration-response data is pooled into a Prism worksheet (log agonist concentration vs. normalized responses, one column per oocyte). The data are plotted in a semi-log plot with mean ± sem points. Non-linear least squares regression fitting to a four parameter logistic function [log(agonist) vs. response with variable slope) will result in the following fitted parameters and errors (SEM): Minimum (bottom), Maximum (top), Hill slope (nH), and log(EC50). Because the data are leak-corrected, it is appropriate to constrain the minimum to be zero in the fit, which will reduce the errors in other fitted parameters. For left-shift analyses, data for both GABA concentration-responses can be combined in the Prism worksheet (as A and B data sets) and simultaneously fitted. This results in fitted parameters for both data sets as well as a statistical analysis determining the probability that the results are identical (the null hypothesis). The fits can also be constrained so that only the EC50 values are compared (see note 20).

3. Spontaneous activation and maximum GABA efficacy

Normalized values for and are simply pooled and the mean ± sem calculated. is an initial estimate of spontaneous open probability, and assuming that maximal GABA plus alphaxalone open 100% of receptors, is the inverse of GABA efficacy.

4. Data renormalization for MWC co-agonist model fitting

Whereas descriptive fitting is performed on leak-corrected data that is normalized to maximal GABA responses, the MWC co-agonist model is fit to Popen values (Figure 2). Thus, if receptors are spontaneously active (P0 > 0), this basal activity must be added as a non-zero baseline. Furthermore, since GABA may activate less than 100% of receptors, responses must be renormalized so that IGABA+alphax represents the maximum open probability. To do this, normalized data are transformed into estimated Popen values using equation 2:

| (2) |

We transfer average normalized response data from GABA concentration-responses (with and without etomidate) and etomidate concentration-response to an Excel spreadsheet, organizing the data into three columns: GABA concentration; Etomidate concentration; Normalized Response. We input the mean values for and into two cells and then calculate in a fourth column from these values and the normalized responses.

Figure 2. Diagram illustrating corrections for spontaneous gating and maximal GABA efficacy.

The diagram depicts an absolute scale of channel open probability from 0 to 1. In mutant GABAA receptors with spontaneous activation, P0 is greater than 1 and the current carried by open channels can be blocked with picrotoxin (IPTX). In mutant GABAA receptors where maximal GABA efficacy is significantly less than 1, closed GABA-bound channels can be opened using allosteric enhancers such as alphaxalone. Rescaling leak-corrected, normalized data to the full Popen range is necessary before fitting with the allosteric mechanism.

5. Fitting MWC co-agonist parameters

The following procedure describes using Origin 6.1 for this non-linear least-squares fit. Prism 5.0, which supports global fitting procedures to multiple data sets, can also be used for this fit once the new equation is added to its non-linear least-squares repertoire.

Data for GABA concentrations, etomidate concentrations, and are transferred or imported from an Excel spreadsheet into a three-column Origin Worksheet with the following headers: GABA, ETO, Popen. GABA concentration-response data can be plotted on a semi-log plot of GABA vs. Popen. The nonlinear least squares fitting module is opened and a new user-defined equation is created to enable fits to the MWC co-agonist model (equation 3):

| (3) |

In the function editor, we named our function ‘MWC_coagonist’ and added it to the ‘Growth/Sigmoidal’ group of functions that also contains Logistic equations. The Parameter names are: L0,Kg,c,Ke,d,n. Independent variables are: gaba,eto. Dependent variable is: Popen. The equation in Y-script is defined as:

| (4) |

Note that equation 4 has one more free parameter than equation 3: the parameter n represents the number of equivalent etomidate sites in the model. We constrain this value to 2 when fitting data for etomidate, but we can also use this equation for other allosteric co-agonists with different numbers of sites (Rüsch and Forman, 2005). L0 in Eq. 3 is a dimensionless basal equilibrium gating variable, approximately P −10. KG and KE are equilibrium dissociation constants for GABA and etomidate binding to inactive states, and c and d are dimensionless allosteric efficacy parameters representing the respective ratios of binding constants in active versus inactive states.

To perform the non-linear least-squares fit in Origin, open the non-linear least squares fitting module. Select the user-defined ‘MWC_coagonist’ function. Click on the ‘Select Dataset’ button and assign Popen, gaba, and eto data columns and ranges. Under ‘More/Options/Constraints’ provide lower bounds of 0 for KG, c, KE, and d. Under ‘Options/Control’ set all the significant digits to 3, tolerance to 0.01, and the maximum number of iterations to 50. Click on ‘Basic Mode’ and insert initial parameters, including the constraint n = 2. Then hit ‘Start Fitting.’ When the fit is satisfactory and you hit ‘Done,’ the fitted equation will be plotted overlaying the GABA concentration-response plot.

Footnotes

Quick-change uses only a single oligonucleotide to replicate circular plasmid DNA. An alternative method we frequently use for site-directed mutagenesis is overlap extension, using two mutagenic oligonucleotides, one for each strand, each paired with a flanking oligonucleotide that encompasses an endonuclease site that can be used to transfer the double-stranded mutated product into a double-cut (gapped) wild-type plasmid.

All solutions are prepared using sterile deionized water with a resistivity of at least 10 MΩ-cm. Oocyte preparation and electrophysiology buffers are prepared as 20 X stocks, stored at 4°C.

Our oocyte injection station is mounted on a steel plate, providing a solid base for the magnetic stand holding the micromanipulator. The Drummond injector was modified with a custom-built brass locking nut that is much longer than the plastic piece delivered with the injector. Without this modification, we found that injection pipette tips moved as the needle plunger was advanced, perhaps because the rotational movement that drives the plunger was translated to the tip. The extra-long locking nut prevents this movement. Stu, I never used this.

A number of commercial superfusion and digitizer/data acquisition systems are available to build a two-microelectrode voltage clamp setup for oocyte electrophysiology. Here, we describe a set-up that incorporates mostly commercially available equipment and a flow cell that is easily built with access to a small milling machine. With a tight budget and access to a workshop, one can build an inexpensive multi-reservoir superfusion system with manual selection valves and one or two electrically-actuated “T” valves downstream. Low-cost digitizer equipment and software to both capture data and control experiments can also be obtained from various sources, (e.g. National Instruments Corp.).

While we fabricate our microelectrodes, pre-fabricated microelectrodes may be purchased from World Precisions Instruments.

Retracting ovary through a small abdominal incision requires continuous gentle traction back and forth, so that small portions of the ovary emerge at a time. If the ovary is very scarred, there may be little option but to enlarge the abdominal opening further.

Try to avoid rupturing oocytes by using forceps to retract connective tissue only about 5 mm apart and pulling the two forceps in opposite directions.

For transfer of clumped oocytes, we use a disposable plastic transfer pipette and cut the end at a bevel to create a larger opening that can accommodate the clumps of oocytes.

Finding the right type (and batch) of collagenase can be a tedious business. Different batches of collagenase have different activities and adjustment in the total incubation time will likely be needed. Worthington Biochemical Corp has a sample program specifically designed for testing different lots of collagenase. When most, but not all of the oocytes appear to be free of connective tissue (i.e. they are no longer in clumps, but move individually), the collagenase treatment is complete. Overtreatment with collagenase can damage membrane proteins and reduce oocyte viability in culture. Under-treatment with collagenase may leave connective tissue that may require other methods of removal, such as rolling on plastic (while immersed in ND96) or manual dissection under a dissecting scope.

This is achieved by first positioning the tip of the pipette next to the bead and then translating the pipette sideways so that a small portion of the tip is snapped off. Alternatively, a pipette tip can be used to break the tip of the glass injector pipette while observing under high magnification on the dissecting microscope.

We prepare a 100ml batch of 1M GABA in water and then store 1 ml aliquots in labeled microcentrifuge tubes at -80 °C. A fresh aliquot is removed each day and kept on ice to minimize the breakdown.

The number of active GABAA receptors on the oocyte surface can change over time (see ref. 12). We usually use a maximally activating GABA concentration for our normalization. Another option is to use a lower non-desensitizing agonist concentration for normalization to shorten the wash-time required after each normalization sweep. A second normalization step is then required to convert responses to fractions of maximal.

Picrotoxin (FW ≈ 600 g/M) is light sensitive and must be stored at room temperature away from windows. It is slow to go into solution-- we add 60 mg picrotoxin to 50 ml ND96 electrophysiology solution in a capped centrifuge tube, cover with aluminum foil, and place on a gently rocking surface for 30 minutes, or until fully dissolved.

We and others have estimated that the open probability of wild-type α1β2γ2L GABAA receptors is 0.0001 or less. The typical dynamic range for oocyte electrophysiology equipment is between 5 nA and 10 μA. Thus, in oocytes where maximal GABA currents are high, a quiet baseline enables detection of spontaneous activity levels of approximately 0.0005 x maximal GABA response.

We test the strength of enhancing activity by adding the enhancer to a low concentration of GABA, such as EC10 from GABA concentration-responses. Addition of enhancer should produce at least a three-fold (hopefully higher) increase in the GABA EC10 current response. Note also that alphaxalone is very hydrophobic and should be stored in glass.

Etomidate concentrations over 1 mM inhibit GABAA receptors.

For this reason, we also use glass containers for etomidate and alphaxalone solutions. These hydrophobic drugs will adsorb into plastic.

A simple switch to etomidate plus GABA will likely under-estimate the etomidate enhancement, as etomidate at low concentrations equilibrates slowly with the oocyte membrane.

An attractive feature of the pClamp/Clampfit suite (Molecular Devices) is that both programs can be open during data acquisition. As soon as a sweep is completed and saved, the resulting data file is automatically opened in Clampfit for analysis while the oocyte is undergoing its ND96 wash for several minutes.

Prism also has other useful fitting equations for these analyses including an ‘Allosteric EC50 shift’ equation.

4. Notes

5. References

- Bali M, Jansen M, Akabas MH. GABA-induced intersubunit conformational movement in the GABAA receptor alpha1M1-beta2M3 transmembrane subunit interface: Experimental basis for homology modeling of an intravenous anesthetic binding site. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3083–3092. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6090-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boileau AJ, Baur R, Sharkey LM, Sigel E, Czajkowski C. The relative amount of cRNA coding for gamma2 subunits affects stimulation by benzodiazepines in GABA(A) receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43:695–700. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Ghansah E, Chen Y, Ye J, Weiss DS. Desensitization mechanism of GABA receptors revealed by single oocyte binding and receptor function. 2002;22:7982–7990. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-07982.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Wang R, Barot S, Weiss DS. Stoichiometry of a recombinant GABAA receptor. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5415–5424. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-17-05415.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Weiss DS. Allosteric activation mechanism of the alpha1beta2gamma2 gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor revealed by mutation of the conserved M2 leucine. Biophys J. 1999;77:2542–2551. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(99)77089-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai R, Ruesch D, Forman SA. Gamma-Amino Butyric Acid Type A Receptor Mutations at beta2N265 Alter Etomidate Efficacy While Preserving Basal and Agonist-dependent Activity. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:774–784. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181b55fae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill-Venning C, Belelli D, Peters JA, Lambert JJ. Subunit-dependent interaction of the general anaesthetic etomidate with the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120:749–756. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain SS, Ziebell MR, Ruesch D, Hong F, Arevalo E, Kosterlitz JA, Olsen RW, Forman SA, Cohen JB, Miller KW. 2-(3-Methyl-3H-diaziren-3-yl)ethyl 1-(1-phenylethyl)-1H-imidazole-5-carboxylate: A derivative of the stereoselective general anesthetic etomidate for photolabeling ligand-gated ion channels. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2003;46:1257–1265. doi: 10.1021/jm020465v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurd R, Arras M, Lambert S, Drexler B, Siegwart R, Crestani F, Zaugg M, Vogt KE, Ledermann B, Antkowiak B, Rudolph U. General anesthetic actions in vivo strongly attenuated by a point mutation in the GABA(A) receptor beta3 subunit. FASEB J. 2003;17:250–252. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0611fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GD, Chiara DC, Sawyer GW, Husain SS, Olsen RW, Cohen JB. Identification of a GABAA receptor anesthetic binding site at subunit interfaces by photolabeling with an etomidate analog. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11599–11605. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3467-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds DS, Rosahl TW, Cirone J, O’Meara GF, Haythornthwaite A, Newman RJ, Myers J, Sur C, Howell O, Rutter AR, Atack J, Macaulay AJ, Hadingham KL, Hutson PH, Belelli D, Lambert JJ, Dawson GR, McKernan R, Whiting PJ, Wafford KA. Sedation and anesthesia mediated by distinct GABA(A) receptor isoforms. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8608–8617. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-24-08608.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch D, Forman SA. Classic benzodiazepines modulate the open-close equilibrium in alpha1beta2gamma2L gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:783–792. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200504000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch D, Zhong H, Forman SA. Gating allosterism at a single class of etomidate sites on alpha1beta2gamma2L GABA-A receptors accounts for both direct activation and agonist modulation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20982–20992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400472200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart DS, Desai R, Cheng Q, Liu A, Forman SA. Tryptophan mutations at azi-etomidate photo-incorporation sites on α1 or β2 subunits enhance GABAA receptor gating and reduce etomidate modulation. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:1687–1695. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.050500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Uchida I. Mechanisms of etomidate potentiation of GABAA receptor-gated currents in cultured postnatal hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience. 1996;73:69–78. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong H, Rusch D, Forman SA. Photo-activated azi-etomidate, a general anesthetic photolabel, irreversibly enhances gating and desensitization of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:103–112. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000296074.33999.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]