The effects of hypercholesterolemia on host defense and TB immunopathology may depend on the types of elevated lipoprotein particles.

Keywords: apoplipoprotein E, cell death, foamy macrophages, host defense, hypercholesterolemi, low-density lipoprotein receptor, Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Abstract

The prevalence of hypercholesterolemia is rising in industrialized and developing countries. We reported previously that host defense against Mtb was impaired by hypercholesterolemia in ApoE−/− mice, raising the possibility that people with HC could be more vulnerable to TB. The present study examined whether TB immunity was similarly impaired in a different hypercholesterolemic model, LDL-R−/− mice, which developed comparable elevation of total serum cholesterol as ApoE−/−mice when fed HC or LC diets. Like ApoE−/− mice, LDL-R−/− mice had an exaggerated lung inflammatory response to Mtb with increased tissue necrosis. Inflammation, foamy macrophage formation, and tissue necrosis in LDL-R−/− mice increased with the degree of hypercholesterolemia. Unlike ApoE−/− mice, LDL-R−/− mice fed a HC diet mounted a timely and protective adaptive immune response that restricted mycobacterial replication comparably with WT mice. Thus, ApoE−/− and LDL-R−/− mice share a cholesterol-dependent hyperinflammatory TB phenotype but do not share the impairment of adaptive immunity found in ApoE−/− mice. The impact of hypercholesterolemia on TB immunity is more complex than appreciated by total cholesterol alone, possibly reflecting the different functional effect of specific lipoprotein particles.

Introduction

Metabolic disorders can have a profound impact on the immune system, as evidenced by the increased susceptibility of people with diabetes to a broad range of infectious agents and the recognition of atherosclerosis as an inflammatory disease. Hypercholesterolemia is a growing health problem faced by industrialized and developing nations [1], yet outside of the context of atherosclerosis, our understanding of how it might affect other aspects of immunity, including host defense, is limited. A better understanding of how hypercholesterolemia influences the immune system could provide novel insights to the full spectrum of its associated health risks.

ApoE−/− mice and LDL-R−/− mice are two hypercholesterolemic models used extensively in atherosclerosis research. Work with ApoE−/− mice or LDL-R−/− mice has demonstrated impaired host defense to Candida albicans, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella typhimurium, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus [2–7]. Proposed mechanisms of susceptibility include greater availability of lipids as a nutrient source for invading pathogens, detoxification of LPS by ApoE, reduced phagocytic capacity, and impaired cytotoxic T lymphocyte activation. We reported previously that hypercholesterolemic ApoE−/− mice are highly susceptible to Mtb. The immunological mechanism of susceptibility was delayed priming of the adaptive immune response [8]. TB susceptibility was not caused by ApoE−/− per se, as only ApoE−/− mice fed a HC diet had a severely compromised immune response.

The LDL-R regulates plasma cholesterol by removing intermediate-density lipoprotein and LDL, whereas ApoE has an important role in the receptor-mediated uptake of VLDL, LDL, and chylomicrons. As a consequence of these differences, LDL-R−/− mice have a greater proportion of LDL and a lower proportion of VLDL cholesterol compared with ApoE−/− mice [9, 10]. In the present study, the TB susceptibility of LDL-R−/− mice was examined in a low-dose Mtb aerosol infection model. LDL-R−/− mice have total serum cholesterol similar to ApoE−/− mice when fed LC or HC diets. LDL-R−/− lung-tissue involvement with inflammation after Mtb infection was dependent on the severity of hypercholesterolemia, similar to our findings for ApoE−/− mice. However, the kinetics of lung inflammation in LDL-R−/− was slower, and lung immunopathology was less extensive than seen for ApoE−/− mice. In contrast to ApoE−/− HC mice, LDL-R−/− HC mice were able to restrict Mtb growth comparable with WT mice. These findings suggest that the cholesterol-dependent TB phenotypes of hyperinflammation and delayed adaptive immune response have a distinct mechanistic basis. The effects of hypercholesterolemia on host defense and TB immunopathology may vary depending on the specific types of lipoprotein particles that are elevated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

C57BL/6, ApoE−/−, and LDL-R−/− mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) or bred at the University of Massachusetts Medical School (Worcester, MA, USA). Experiments were performed under protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and Institutional Biosafety Committee.

Reagents

Mice were fed a LC (0.12% cholesterol, standard rodent chow) or HC (1.25% cholesterol, 0.5% sodium cholate, D12109C; Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) diet, 2 weeks before and during the experiment. Both diets contain an equivalent amount of carbohydrate, protein, and fat. Serum cholesterol measurement was performed as described [8].

Mtb infection

Aerosol infections with Mtb Erdman were performed in a Glas-Col inhalation exposure system (Glas-Col, Terre Haute, IN, USA) set to deliver ∼50 CFU to the lungs, as described previously [8]. Two mice were killed 24 h p.i. to confirm the delivered dose. Enumeration of bacteria was done as described previously [8].

Histopathology

Lungs tissues were prepared for histology, as described previously [8]. Paraffin tissue sections were used for all staining techniques except for Oil Red staining, which used frozen tissue sections. H&E-stained lung sections were analyzed using Spot Advanced for Windows (Version 4.6, Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI, USA) or NIS-Elements AR for Windows (Version 3.10, Sp3, Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY, USA). Lung area involved with inflammation was calculated by dividing the cumulative area of discrete lesions by the total lung surface area surveyed at ×20 magnification. TUNEL staining was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and counterstained with 1% methyl green. As a negative control, sections were stained in the absence of the primary antibody. Thymus tissue sections were used as a positive control. Frozen lung sections were stained with Oil Red O, high-resolution images of TB lesions were generated by merging multiple ×100 images, and quantitative measurements were made with NIS-Elements AR. The lipid-body content of TB lesions was expressed as the cumulative area of all lipid bodies, divided by the lesion area (minus the cumulative area of the air spaces), and multiplied by 100. All staining procedures were done by the Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center Morphology Core Facility at University of Massachusetts Medical School.

IFN-γ ELISPOT

Mouse IFN-γ ELISPOT assays were performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations (mouse IFN-γ ELISPOT Pair, BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA). Lung leukocytes (1×104 or 4×104) were plated in duplicate and incubated (48 h, 37°C 5% CO2) in the presence of media only, 2 μg/ml Con A, 2 μg/ml Mtb Erdman CFP, or 10 μM Ag85A243-260 QDAYNAGGGHNGVFDFP H-2b-restricted epitope peptide (21st Century Biochemicals, Marlboro, MA, USA). Con A-stimulated cells served as a positive control. Uncoated wells and wells without cells were used as negative controls. The number and size of spots were measured with an automated ELISPOT reader (ImmunoSpot, CTL, Shaker-Heights, OH, USA), using CTL ImmunoSpot Academic Software for Windows (Version 4.0, CTL). Results were calculated as spots/105 CD4+ T cells, based on the frequency of CD4+ T cells (analyzed by flow cytometry) and mean number of spots from each duplicate.

Statistical analysis

Nonparametric ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer post-test and one-way ANOVA with Dunn's post-test, t-test, and Mann-Whitney test were preformed with GraphPad for Windows (Version 5.x; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Mycobacterial burden in LDL-R−/− mice

We reported previously that hypercholesterolemic ApoE−/− HC mice fail to mount a timely adaptive immune response to Mtb and die within 4 weeks p.i. with massive neutrophilic lung inflammation [8]. Impaired priming of the adaptive immune response substantially delayed the expression of protective immunity in these mice, allowing virtually uncontrolled bacterial growth. To further explore the relationship between hypercholesterolemia and TB susceptibility, WT, LDL-R−/−, and ApoE−/− mice were evaluated in a low-dose aerosol Mtb infection model. Mice were fed a LC or HC diet, starting 2 weeks before and during each experiment. After 2 weeks on their respective diets, mean serum cholesterol for WT HC, LDL-R−/− LC, LDL-R−/− HC, and ApoE−/− HC mice was 193 mg/dl, 380 mg/dl, 2308 mg/dl, and 2129 mg/dl, respectively (n=4–5). Total serum cholesterol, which is a combined measure of VLDL, LDL, and HDL, was thus comparable between LDL-R−/− mice and ApoE−/− mice. WT LC mice were not used, as we previously found that their TB phenotype did not differ from WT HC mice [8].

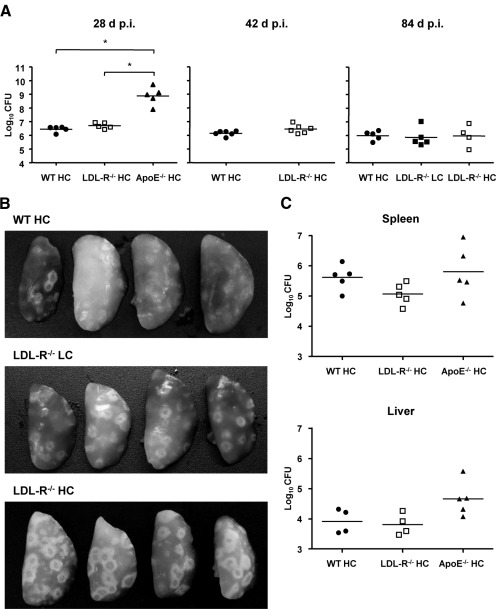

In our initial survey of the TB disease phenotype of LDL-R−/− mice, we infected WT, LDL-R−/−, and ApoE−/− mice fed a HC diet with ∼50 CFU of Mtb Erdman by aerosol and measured bacterial lung burden 28 days later (Fig. 1A, left panel). Mice were fed a HC diet, as ApoE−/− mice fed this diet were previously found to have the greatest impairment of TB immunity [8]. WT HC and LDL-R−/− HC mice had a comparable bacterial load, which was ∼2.5 logs lower than ApoE−/− HC mice. Bacterial burden in ApoE−/− HC mice (8.7 logs CFU) was consistent with our previous findings. C57BL/6, the background strain of the ApoE−/− mice and LDL-R−/− HC mice used in this study, is relatively TB-resistant with a median survival time > 250 days after aerosol infection. These mice hold lung bacterial load at a stationary level but eventually expire from progressive lung inflammation with a preterminal increase in bacterial load [11, 12]. To determine whether TB progresses faster in LDL-R−/− HC mice, lung CFU was measured 42 and 84 days p.i. with each time-point representing an independent experiment (Fig. 1A). Lung bacterial burden did not differ between WT HC and LDL-R−/− HC at either time-point, remaining at a plateau level of ∼6 logs CFU for both groups at all three time-points. LDL-R−/− LC mice had a bacterial lung burden similar to WT HC and LDL-R−/− HC mice, 84 days p.i. ApoE−/− HC mice fail to control Mtb replication and expire within 30 days after aerosol infection, so they could not be included at later time-points [8]. Despite the capacity of LDL-R−/− HC mice to restrict Mtb replication, TB lesions appeared more pronounced on LDL-R−/− HC lungs compared with WT HC lungs by gross pathology (Fig. 1B). LDL-R−/− HC did not develop the massive abscess-like lesions, which we reported for ApoE−/− HC mice with TB. Spleen and liver bacterial burden did not differ significantly among WT HC, LDL-R−/− HC, and ApoE−/− HC mice, 28 days p.i. (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. LDL-R−/− mice are able to control Mtb growth in the lung, in contrast to ApoE−/− HC mice where bacillary growth is unrestricted.

(A) Bacterial lung burden of WT, LDL-R−/−, and ApoE−/− mice fed a LC or HC diet, 28, 42, and 84 days (d) p.i., with ∼50 CFU Mtb. Individual data points are shown as log10 CFU with the geometric mean (horizontal lines). *P < 0.05 (n=4–6). (B) LDL-R−/− HC lungs had more extensive gross TB pathology than WT HC and LDL-R−/− LC lungs. Images showing the left lung lobes of WT HC, LDL-R−/− LC, and LDL-R−/− HC, 42 days p.i. (n=4). (C) Bacterial spleen and liver burden of WT, LDL-R−/−, and ApoE−/− mice fed a HC diet, 28 days p.i. with Mtb. Individual data points are shown as log10 CFU with the geometric mean (horizontal lines; P was not significant; n=4 or 5).

LDL-R−/− mice have a normal adaptive immune response

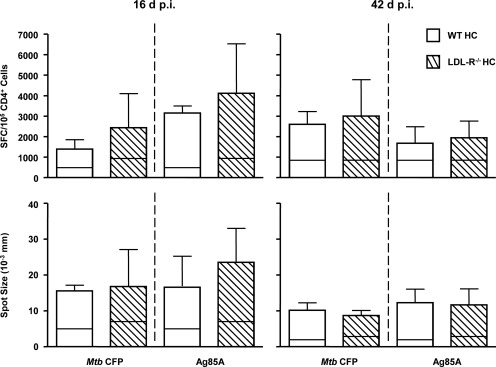

After aerosol infection of C57BL/6 mice, Mtb grows exponentially for ∼3 weeks until adaptive immunity causes the bacterial burden to plateau. We observed a markedly delayed adaptive immune response to TB in ApoE−/− HC mice, and as a consequence, logarithmic growth of Mtb continued until the mice expired after 4 weeks with a very high bacterial lung burden [8]. The similar bacterial lung burden of WT HC and LDL-R−/− HC mice up to 84 days p.i. indicated that the adaptive immune response of LDL-R−/− HC mice to Mtb was not grossly impaired by hypercholesterolemia. To confirm that impression, IFN-γ ELISPOT was used to assess the kinetics and strength of the adaptive immune response of LDL-R−/− mice to Mtb. Lung leukocytes from WT HC and LDL-R−/− HC mice were cultured with Mtb CFP, the Ag85A243-260 H-2b-restricted epitope peptide, Con A, or media. IFN-γ responses were measured by ELISPOT, 16 and 42 days p.i. (Fig. 2). Incubation with Con A or media served as positive and negative controls, respectively (Con A; data not shown). The frequency of CD4+ cells was determined by flow cytometry and used to calculate the number of SFC/105 CD4+ cells. WT HC and LDL-R−/− HC lung leukocytes had a similar frequency of TB antigen-specific CD4+ T cells at early and late time-points. Spot size also did not differ between WT HC and LDL-R−/− HC lung leukocytes at either time-point. As spot size correlates with the amount of IFN-γ secreted by a cell, this indicated that IFN-γ secretion by LDL-R−/− HC lung leukocytes was not impaired. Lung leukocytes from uninfected WT HC and LDL-R−/− HC did not respond to Mtb CFP or Ag85A243-260, but they did respond to nonspecific TCR stimulation with Con A (data not shown; n=3).

Figure 2. The kinetics and magnitude of the Mtb-specific T cell response are comparable between WT HC and LDL-R−/− HC mice.

Lung leukocytes isolated from WT HC and LDL-R−/− HC mice, 16 and 42 days after aerosol infection with Mtb, were cultured on IFN-γ ELISPOT plates in the presence of control media, Con A (not shown), Mtb CFP, or an Ag85A243-620 (Ag85A) peptide. The proportion of CD4+ lung leukocytes, as determined by flow cytometry, was used to calculate the number of CD4+ cells present. The number of SFC/105 CD4+ cells (upper plots) and average spot size (lower plots) is shown, and the horizontal lines inside each bar represent the average response of cells not stimulated with exogenous antigen. Results are representative of one experiment, and mean values are shown with +sd. P was not significant (n=5).

TB alters lipoprotein profiles

Infection and inflammation can have profound effects on lipoprotein metabolism, clearance, and composition [13]. There has been recent speculation that Mtb use lipids such as cholesterol as a carbon during latency or chronic infection. The Mtb genome has 21 annotated lipase and esterase genes [14], and Mtb mutants with defects in cholesterol uptake fail to establish robust, chronic infections in mice [15]. We reported previously that serum total cholesterol, preinfection and p.i. (28 days p.i.), did not differ for WT HC or ApoE−/− HC mice [8]. Here, we compared the serum total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, and triglycerides of uninfected and infected (42 days p.i.) WT HC, LDL-R−/− LC, and LDL-R−/− HC mice after 56 days on their respective diets (Table 1). A number of differences were identified within groups, but there was no discernable pattern to the differences between uninfected and infected serum lipoprotein profiles. The largest difference was a dramatic drop in serum triglycerides for infected LDL-R−/− HC in mice. Although Mtb has a lipase capable of hydrolyzing long-chain triacylglycerol [16], the kinetics and level of its expression during infection are not known. Whether the lipoprotein differences identified here relate to Mtb-mediated lipoprotein catabolism, Mtb directly altering host lipoprotein metabolism, or inflammation altering lipoprotein metabolism needs further investigation.

Table 1. Comparison of Serum Lipid Profiles of Mice in the Absence or Presence of TB.

| Total cholesterol |

HDL |

LDL |

Triglycerides |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean ± sd (mg/dl) | mean ± sd (mg/dl) | mean ± sd (mg/dl) | mean ± sd (mg/dl) | |

| WT HC | ||||

| Uninfected | 249 ± 8 | 123 ± 6 | 37 ± 4 | 76 ± 7 |

| TB | 203 ± 16 | 87 ± 11 | 33 ± 2 | 92 ± 21 |

| P | <0.05 | <0.05 | n.s. | n.s. |

| LDL-R−/− LC | ||||

| Uninfected | 295 ± 41 | 84 ± 11 | 90 ± 16 | 137 ± 5 |

| TB | 404 ± 35 | 109 ± 5 | 128 ± 14 | 196 ± 57 |

| P | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | n.s. |

| LDL-R−/− HC | ||||

| Uninfected | 2316 ± 71 | 24 ± 3 | 485 to >800a | 527 ± 154 |

| TB | 2321 ± 43 | 25 ± 6 | 502 to >800a | 190 ± 29 |

| P | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | <0.05 |

Blood was collected from mice after 56 days on a LC or HC diet. Mice with TB were infected with ∼50 CFU Mtb by aerosol, 14 days after starting their diet, and were 42 days p.i. when blood was collected. Serum total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, and triglycerides were measured and are shown as the mean (mg/dl) ± sd. P < 0.05 (n=3–4).

Minimum and maximum values are shown, as some samples exceeded the detection range of assay.

Greater lung inflammation in LDL-R−/− mice

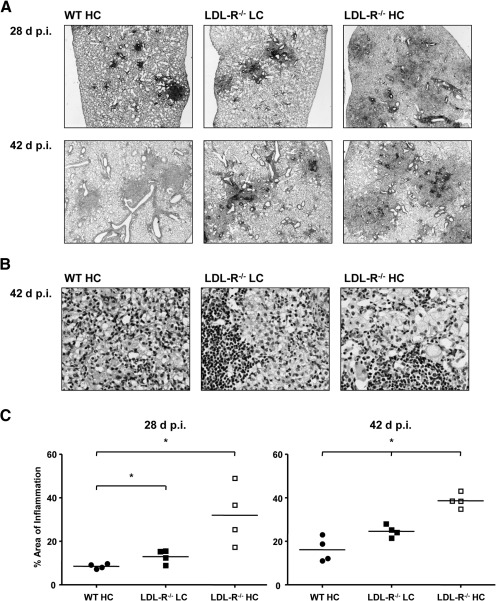

Gross lung pathology suggested that LDL-R−/− HC mice had a greater inflammatory response to TB compared with WT HC mice. To extend these observations, WT HC, LDL-R−/− LC, and LDL-R−/− HC mice were infected by aerosol with Mtb and lungs prepared for histopathology, 28 and 42 days p.i. Representative images of H&E-stained lung sections are shown in Fig. 3A and B. To quantify lung inflammation, morphometric analysis of H&E-stained lung sections was used. The cumulative area of inflammatory lesions was divided by the total area of lung tissue surveyed to derive the percent lung-tissue involvement with inflammation (Fig. 3C). LDL-R−/− mice fed a LC or HC diet had greater lung inflammation than WT HC mice. The kinetics of inflammation appeared to be strongly influenced by the degree of hypercholesterolemia, as LDL-R−/− HC mice had greater inflammation earlier than LDL-R−/− LC mice. Interestingly, the average area of lung inflammation remained virtually unchanged in LDL-R−/− HC mice between 28 and 42 days p.i. (albeit with less variation at 42 days), suggesting that the initially accelerated inflammatory response in the lung reached a plateau. LDL-R−/− mice fed a LC diet had only marginally greater lung inflammation than WT HC mice, indicating that increased lung inflammation in LDL-R−/− mice was dependent on the severity of hypercholesterolemia as opposed to an effect of LDL-R−/−, independent of cholesterol. The comparable bacterial burden in LDL-R−/− HC mice and WT HC mice also indicates that the exaggerated lung inflammation in the former is driven by factors other than the burden of ligands for PRRs presented to the immune system.

Figure 3. TB lung immunopathology increases with the level of serum cholesterol.

(A) Representative images of H&E-stained lung sections of WT HC, LDL-R−/− LC, and LDL-R−/− HC mice, 28 and 42 days p.i. with Mtb (n=4; original magnification, ×20). (B) Representative images of H&E-stained lung sections of WT HC, LDL-R−/− LC, and LDL-R−/− HC mice, 42 days p.i. with Mtb (n=4; original magnification, ×400). (C) The proportion of WT HC, LDL-R−/− LC, and LDL-R−/− HC lung tissue involved with inflammation, 28 and 42 days p.i. with Mtb. Total cross-sectional lung area and areas of inflammation were measured on H&E-stained lung sections by quantitative videomicroscopy to define the percent total area involved with inflammation. Individual data points are shown with horizontal lines indicating the mean. *P < 0.05 (n=4).

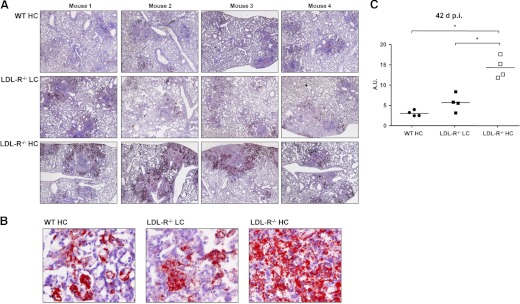

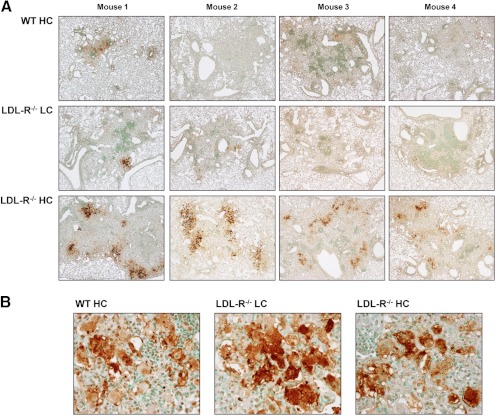

Foamy macrophages were observed in TB lesions of WT HC, LDL-R−/− LC, and LDL-R−/− HC mice (Fig. 3B). Macrophages with a large number of lipid bodies take on a foamy appearance when the paraffin-embedding process extracts theirs lipids and leaves behind bubble-like spaces in their cytoplasm. To measure the lipid-body content of TB lesions, lungs from WT HC, LDL-R−/− LC, and LDL-R−/− HC mice, 42 days p.i., were fixed and frozen, a process that does not extract lipids, and lung sections were stained with Oil Red O, causing lipid bodies to appear bright red. For all treatment groups, the bulk of the lipids was stored in lipid bodies along the periphery of the TB lesion, whereas lipid bodies with smaller amounts of lipids were found in the inner regions of the lesion (Fig. 4A and B). Quantitative videomicroscopy was used to measure the cumulative area of lipid droplets; the cumulative area of “open spaces”, i.e. airways, alveoli, and blood vessels; and the area of the TB lesion. These values were used to express the lipid-body content of TB lesions relative to lesion size minus open spaces (Fig. 4C). LDL-R−/− HC TB lesions had significantly higher lipid-body content than the other groups, and there was a trend for LDL-R−/− LC lesions to have higher lipid-body content than WT HC lesions.

Figure 4. Hypercholesterolemia promotes foamy macrophage formation in TB lesions.

(A) Foamy macrophages were identified by Oil Red O staining of lipid bodies in lung sections from WT HC, LDL-R−/− LC, and LDL-R−/− HC mice, 42 days p.i. with Mtb (original magnification, ×20). (B) Representative images of Oil Red O-stained lung sections of foamy macrophages, 42 days p.i. at higher magnification (original, ×400). (C) Lipid-body content of WT HC, LDL-R−/− LC, and LDL-R−/− HC lung TB lesions, 42 days p.i., expressed as arbitrary units (A.U.). The area of individual lipid droplets, lesion area, and air-space area within the lesion was measured by quantitative videomicroscopy. Arbitrary units equal the cumulative area of lipid bodies, divided by the lesion area (minus the area of open spaces), and multiplied by 100. Results are representative of one experiment. Lipid bodies are stained a bright red. *P < 0.05 (n=4).

Foamy macrophages are a common feature of human and murine TB lesions whose origins and functions in this setting are not well understood. Mycobacterial products such as oxygenated mycolic acids are one stimulus proposed to induce foam cell formation [17]. It is speculated that lipid bodies inside macrophages serve as energy reservoirs for Mtb during latency [18], and bacilli have been found in close proximity to lipid bodies in human tissue biopsies, supporting the concept that host lipids provide a carbon source to the pathogen [17].

Despite the greater number of foamy macrophages in LDL-R−/− HC TB lesions, these mice did not have a higher bacterial burden than WT HC mice. There are several possible explanations for this phenomenon: 1) the adaptive immune response mounted by LDL-R−/− HC mice may have driven the bacterium toward stationary persistence despite the increased availability of cholesterol, 2) the cholesterol in LDL-R−/− HC foamy macrophages may not be in a form readily metabolized by or accessible to the mycobacteria, and 3) a threshold amount of cholesterol is required for persistence, and more cholesterol is of no additional benefit.

Lipid bodies were viewed previously as inert depots, but mounting evidence suggests that they are sites of substantial metabolic activity and cytokine storage, depending on the stimuli initiating their formation [19]. ox-LDL was shown to induce macrophages to become foamy and form LT-synthesizing lipid bodies, and the oxidative environment of TB lesions would allow ample opportunity for LDL oxidation in LDL-R−/− HC mice [20]. LTs are strong, proinflammatory mediators stimulating cell recruitment and increasing vascular permeability, thus LDL-R−/− HC TB lesions may be sites that promote the formation of lipid bodies synthesizing proinflammatory LTs. Eicosanoids such as PGE2, LTB4, and lipoxin A4 have been shown to influence mycobacterial immunity and macrophage cell death [21–23].

Cell death increases with hypercholesterolemia

We previously observed massive neutrophil infiltration and extensive tissue necrosis in ApoE−/− HC lungs, 30 days p.i [8]. Therefore, in the present study, we assessed cell death in WT HC, LDL-R−/− LC, and LDL-R−/− HC lungs by TUNEL staining of lung sections, 28 and 42 days p.i. Greater TUNEL staining of LDL-R−/− HC TB lesions compared with WT HC and LDL-R−/− LC TB lesions was observed as early as 28 days p.i. (data not shown), but this difference became far more evident at 42 days (Fig. 5A). Similar to the Oil Red O lipid-staining pattern, the most intense TUNEL staining was around the periphery of the LDL-R−/− HC TB. Many of the dead cells in these intensely TUNEL-positive regions were macrophages, and these regions were often abutted by less-intensely TUNEL-stained foamy macrophages. Close proximity of foamy macrophages to areas of necrosis has also been reported in human LN biopsies from TB patients [17], and foamy macorphages have been associated with caseous necrosis [24]. TUNEL-positive foamy macrophages were less commonly found in association with WT HC and LDL-R−/− LC lesions. A higher proportion of the TUNEL-positive cells in WT HC and LDL-R−/− LC lesions appeared to be lymphocytes.

Figure 5. Hypercholesterolemia promotes cell death, necrosis, and foamy macrophage formation in TB lesions.

(A) TUNEL was used to detect cell death in lung sections from WT HC, LDL-R−/− LC, and LDL-R−/− HC mice, 42 days p.i. with Mtb (original magnification, ×40). (B) Representative images of TUNEL-stained lung sections of foamy macrophages, 42 days p.i. at higher magnification (original, ×400). TUNEL-stained cells are identified by a dark-brown insoluble dye precipitate. Results are representative of one experiment (n=4).

The TUNEL-staining pattern of foamy macrophages was diverse (Fig. 5B). Some foamy macrophages had TUNEL staining in the cytoplasm and the nucleus, whereas others had exclusively cytoplasmic or exclusively nuclear TUNEL staining. In the course of apoptosis, DNA fragmentation occurs in the nucleus; fragmented DNA may be seen in the cytoplasm as a later event if secondary necrosis ensues. The appearance of TUNEL staining exclusively in the cytoplasm of some macrophages in LDL-R−/− HC lesions suggests that these foamy macrophages were not apoptotic and rather, had acquired exogenous DNA by efferocytosis. Macrophages involved in the removal of dead cells have been reported to develop a foamy phenotype as they store the ingested membrane lipids from dead cells [25, 26]. The cytoplasmic TUNEL staining of these foamy macrophages and their close proximity to dead cells would be consistent with such a process. TUNEL-negative foamy macrophages were also present in TB lesions, suggesting that uptake of lipids from dead cells was not the only cause of foam cell formation. Multinucleated foamy macrophages were also present, and some had one or more TUNEL-positive nuclei. Cell death correlated with the degree of hypercholesterolemia as TB lesions of LDL-R−/− mice fed a HC diet had dramatically more dead cells than lesions of LDL-R−/− mice fed a LC diet.

Biological significance

WT C57BL/6 mice have high HDL and low LDL, even when fed a HC “Western” diet (see Table 1), making them a poor model of human hypercholesterolemia, which is commonly characterized by low HDL and high LDL. To address this issue, researchers have developed the ApoE−/− and LDL-R−/− murine hypercholesterolemia models, which have been used extensively as animal models of atherosclerosis. A Western diet is often used with these models to accelerate disease progression. LDL is the major circulating lipoprotein in hypercholesterolemic LDL-R−/− mice and in most hypercholesterolemic humans. Whereas dietary choices are believed to be the most common cause of hypercholesterolemia in people, rare mutations in the LDL-R, ApoB, and proprotein convertase subtilsen/kexin type 9 genes also cause hypercholesterolemia [27]. These mutations have been studied mostly in the context of cardiovascular disease, but a link between Chlamydia pneumoniae and coronary artery disease has been reported for people with a heterozygous mutation in the LDLR gene [28]. In contrast to LDL-R−/− mice, VLDL is the major circulating lipoprotein in ApoE−/− mice, and VLDL is often elevated in people with type II diabetes [29]. Diabetes is associated with increased susceptibility to many types of infections including TB. We reported previously that diabetic mice with chronic hyperglycemia (>3 months) but not acute (<1 month) are highly susceptible to TB [30]. Our past and current findings suggest that dyslipidemias, common in type II diabetes, may also contribute to increased TB susceptibility in that population.

Atherosclerosis is now viewed as a primarily inflammatory disease of large and medium-sized arteries, with infiltration of foam cells, macrophages, DCs, and lymphocytes in the vascular intima and adventitia [31]. Similar mechanisms may underlie the TB immunopathology of ApoE−/− HC and LDL-R−/− HC mice. The exaggerated immunopathology and increased cell death in LDL-R−/− HC lungs coincided with the formation of TB lesions. Lung inflammation was not a generalized phenomenon, as it was limited to sites of infection. Taken together, our data suggest that high levels of LDL cholesterol predispose LDL-R−/− HC mice for excessive inflammation and cell death in response to the presence of Mtb in the lung. There are several plausible mechanisms for this outcome. Uptake of ox-LDL through scavenger receptors is unregulated, which can lead to high intracellular levels of free cholesterol [32]. This could promote inflammation by at least two mechanisms. It was reported that cholesterol microcrystals can activate the NLP3 inflammasome, leading to proinflammatory cytokine production [33]. High intracellular cholesterol can also promote cell death. The extensive cell death and necrosis in LDL-R−/− HC TB lesions may have been another driving force behind the increased immunopathology. Necrotic cell death is an inflammatory process, wherein cell contents released into extracellular spaces may damage nearby cells and stimulate neutrophil recruitment [34–36].

The current study complements our earlier finding that severe hypercholesterolemia in ApoE−/− HC mice increases TB susceptibility. ApoE−/− mice and LDL-R−/− mice fed a HC diet share the phenotype of an exaggerated inflammatory response to TB, but only ApoE−/− mice had a significantly impaired adaptive immune response. Whether this difference relates to the biochemical effects of different lipoprotein distributions of ApoE−/− mice (high VLDL cholesterol) versus LDL-R−/− mice (high LDL cholesterol) or some other cholesterol-dependent mechanism linked to ApoE−/− remains to be determined. However, this difference suggests a previously unanticipated degree of complexity in the influence of dysplipidemias on protective immunity. Diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemias, previously associated with developed nations in the west, are increasing dramatically in frequency in emerging economies of Asia where TB rates are also high. Our findings in mouse models of hypercholesterolemia suggest that such disorders could have a clinically significant impact on the characteristics and severity of comorbid TB in human populations. This question has not been addressed previously in human clinical TB studies but should be considered based on the recent confluence of TB disease and metabolic syndromes, particularly in India and China.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH Grant HL081149 (H.K.). Core resources used for this work are supported by the Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center Grant DK32520. The authors thank Laura Fenton-Noriega and Antonela Dhamko for technical assistance with data collection and animal care.

SEE CORRESPONDING EDITORIAL ON PAGE 843

- −/−

- deficient

- ApoE

- apolipoprotein E

- ApoE−/−

- B6.129P2-Apoe/J

- CFP

- culture-filtrate protein

- CTL

- Cellular Technology Ltd.

- HC

- high cholesterol

- LC

- low cholesterol

- LDL-R−/−

- B6.129S7-Ldlr/J

- LT

- leukotriene

- Mtb

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- ox-LDL

- oxidized-LDL

- p.i.

- postinfection

- SFC

- spot-forming cell

- TB

- tuberculosis

AUTHORSHIP

G.W.M. and T.V. conceived of and performed the experiments. G.W.M., T.V., and H.K. wrote the paper.

DISCLOSURES

None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization (2002) World Health Report 2002; Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vonk A. G., De Bont N., Netea M. G., Demacker P. N., van der Meer J. W., Stalenhoef A. F., Kullberg B. J. (2004) Apolipoprotein-E-deficient mice exhibit an increased susceptibility to disseminated candidiasis. Med. Mycol. 42, 341–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roselaar S. E., Daugherty A. (1998) Apolipoprotein E-deficient mice have impaired innate immune responses to Listeria monocytogenes in vivo. J. Lipid Res. 39, 1740–1743 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Netea M. G., Joosten L. A., Keuter M., Wagener F., Stalenhoef A. F., van der Meer J. W., Kullberg B. J. (2009) Circulating lipoproteins are a crucial component of host defense against invasive Salmonella typhimurium infection. PLoS ONE 4, e4237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Netea M. G., Demacker P. N., Kullberg B. J., Boerman O. C., Verschueren I., Stalenhoef A. F., van der Meer J. W. (1996) Low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice are protected against lethal endotoxemia and severe gram-negative infections. J. Clin. Invest. 97, 1366–1372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. De Bont N., Netea M. G., Demacker P. N., Verschueren I., Kullberg B. J., van Dijk K. W., van der Meer J. W., Stalenhoef A. F. (1999) Apolipoprotein E knock-out mice are highly susceptible to endotoxemia and Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. J. Lipid Res. 40, 680–685 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ludewig B., Jaggi M., Dumrese T., Brduscha-Riem K., Odermatt B., Hengartner H., Zinkernagel R. M. (2001) Hypercholesterolemia exacerbates virus-induced immunopathologic liver disease via suppression of antiviral cytotoxic T cell responses. J. Immunol. 166, 3369–3376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martens G. W., Arikan M. C., Lee J., Ren F., Vallerskog T., Kornfeld H. (2008) Hypercholesterolemia impairs immunity to tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 76, 3464–3472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ishibashi S., Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L., Gerard R. D., Hammer R. E., Herz J. (1993) Hypercholesterolemia in low density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice and its reversal by adenovirus-mediated gene delivery. J. Clin. Invest. 92, 883–893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang S. H., Reddick R. L., Piedrahita J. A., Maeda N. (1992) Spontaneous hypercholesterolemia and arterial lesions in mice lacking apolipoprotein E. Science 258, 468–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mogues T., Goodrich M. E., Ryan L., LaCourse R., North R. J. (2001) The relative importance of T cell subsets in immunity and immunopathology of airborne Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. J. Exp. Med. 193, 271–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rhoades E. R., Frank A. A., Orme I. M. (1997) Progression of chronic pulmonary tuberculosis in mice aerogenically infected with virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuber. Lung Dis. 78, 57–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Khovidhunkit W., Kim M. S., Memon R. A., Shigenaga J. K., Moser A. H., Feingold K. R., Grunfeld C. (2004) Effects of infection and inflammation on lipid and lipoprotein metabolism: mechanisms and consequences to the host. J. Lipid Res. 45, 1169–1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cole S. T., Brosch R., Parkhill J., Garnier T., Churcher C., Harris D., Gordon S. V., Eiglmeier K., Gas S., Barry C. E., III, et al. (1998) Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393, 537–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pandey A. K., Sassetti C. M. (2008) Mycobacterial persistence requires the utilization of host cholesterol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 4376–4380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deb C., Daniel J., Sirakova T. D., Abomoelak B., Dubey V. S., Kolattukudy P. E. (2006) A novel lipase belonging to the hormone-sensitive lipase family induced under starvation to utilize stored triacylglycerol in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 3866–3875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peyron P., Vaubourgeix J., Poquet Y., Levillain F., Botanch C., Bardou F., Daffe M., Emile J. F., Marchou B., Cardona P. J., de Chastellier C., Altare F. (2008) Foamy macrophages from tuberculous patients' granulomas constitute a nutrient-rich reservoir for M. tuberculosis persistence. PLoS Pathog. 4, e1000204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Russell D. G., Cardona P. J., Kim M. J., Allain S., Altare F. (2009) Foamy macrophages and the progression of the human tuberculosis granuloma. Nat. Immunol. 10, 943–948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bozza P. T., Magalhaes K. G., Weller P. F. (2009) Leukocyte lipid bodies—biogenesis and functions in inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1791, 540–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Silva A. R., Pacheco P., Vieira-de-Abreu A., Maya-Monteiro C. M., D'Alegria B., Magalhaes K. G., de Assis E. F., Bandeira-Melo C., Castro-Faria-Neto H. C., Bozza P. T. (2009) Lipid bodies in oxidized LDL-induced foam cells are leukotriene-synthesizing organelles: a MCP-1/CCL2 regulated phenomenon. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1791, 1066–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Divangahi M., Desjardins D., Nunes-Alves C., Remold H. G., Behar S. M. (2010) Eicosanoid pathways regulate adaptive immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Immunol. 11, 751–758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mattos K. A., D'Avila H., Rodrigues L. S., Oliveira V. G., Sarno E. N., Atella G. C., Pereira G. M., Bozza P. T., Pessolani M. C. (2010) Lipid droplet formation in leprosy: Toll-like receptor-regulated organelles involved in eicosanoid formation and Mycobacterium leprae pathogenesis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 87, 371–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Peres C. M., de P. L., Medeiros A. I., Sorgi C. A., Soares E. G., Carlos D., Peters-Golden M., Silva C. L., Faccioli L. H. (2007) Inhibition of leukotriene biosynthesis abrogates the host control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbes Infect. 9, 483–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim M. J., Wainwright H. C., Locketz M., Bekker L. G., Walther G. B., Dittrich C., Visser A., Wang W., Hsu F. F., Wiehart U., Tsenova L., Kaplan G., Russell D. G. (2010) Caseation of human tuberculosis granulomas correlates with elevated host lipid metabolism. EMBO Mol. Med. 2, 258–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rios-Barrera V. A., Campos-Pena V., Aguilar-Leon D., Lascurain L. R., Meraz-Rios M. A., Moreno J., Figueroa-Granados V., Hernandez-Pando R. (2006) Macrophage and T lymphocyte apoptosis during experimental pulmonary tuberculosis: their relationship to mycobacterial virulence. Eur. J. Immunol. 36, 345–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Caceres N., Tapia G., Ojanguren I., Altare F., Gil O., Pinto S., Vilaplana C., Cardona P. J. (2009) Evolution of foamy macrophages in the pulmonary granulomas of experimental tuberculosis models. Tuberculosis (Edinb.). 89, 175–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang X., Li X., Zhang Y. B., Zhang F., Sun L., Lin J., Wang D. M., Wang L. Y. (2011) Genome-wide linkage scan of a pedigree with familial hypercholesterolemia suggests susceptibility loci on chromosomes 3q25-26 and 21q22. PLoS ONE 6, e24838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kontula K., Vuorio A., Turtola H., Saikku P. (1999) Association of seropositivity for Chlamydia pneumoniae and coronary artery disease in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia. Lancet 354, 46–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Winocour P. H., Durrington P. N., Bhatnagar D., Ishola M., Arrol S., Mackness M. (1992) Abnormalities of VLDL, IDL, and LDL characterize insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Arterioscler. Thromb. 12, 920–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Martens G. W., Arikan M. C., Lee J., Ren F., Greiner D., Kornfeld H. (2007) Tuberculosis susceptibility of diabetic mice. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 37, 518–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Galkina E., Ley K. (2009) Immune and inflammatory mechanisms of atherosclerosis (*). Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27, 165–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schmitz G., Grandl M. (2008) Lipid homeostasis in macrophages—implications for atherosclerosis. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 160, 93–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Duewell P., Kono H., Rayner K. J., Sirois C. M., Vladimer G., Bauernfeind F. G., Abela G. S., Franchi L., Nuñez G., Schnurr M., Espevik T., Lien E., Fitzgerald K. A., Rock K. L., Moore K. J., Wright S. D., Hornung V., Latz E. (2010) NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature 464, 1357–1361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yamasaki S., Ishikawa E., Sakuma M., Hara H., Ogata K., Saito T. (2008) Mincle is an ITAM-coupled activating receptor that senses damaged cells. Nat. Immunol. 9, 1179–1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McDonald B., Pittman K., Menezes G. B., Hirota S. A., Slaba I., Waterhouse C. C., Beck P. L., Muruve D. A., Kubes P. (2010) Intravascular danger signals guide neutrophils to sites of sterile inflammation. Science 330, 362–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang Q., Raoof M., Chen Y., Sumi Y., Sursal T., Junger W., Brohi K., Itagaki K., Hauser C. J. (2010) Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature 464, 104–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]