Abstract

Assessment of an individual’s functional ability can be complex. This assessment should also be individualized and adaptable to changes in functional status. In the first article of this series, we operationally defined function, discussed the construct of function, examined the evidence as it relates to assessment methods of various aspects of function, and explored the multi-dimensional nature of the concept of function. In this case report, we aim to demonstrate the utilization of a multi-dimensional assessment method (functional performance testing) as it relates to a high-level athlete presenting with pain in the low back and groin. It is our intent to demonstrate how the clinician should continually adapt their assessment dependent on the current functional abilities of the patients.

Keywords: Functional testing, Physical performance tests, Physical therapy

Background

Clearly delineating the specific source(s) of symptoms in day-to-day clinical practice is often difficult, especially in patients with low back pain (LBP).1 Only a small percentage of individuals with LBP have been shown to demonstrate an identifiable pathoanatomical source.2 Specifically differentiating the spine versus the hip as the primary pain generator is currently limited primarily to impairment assessment,3,4 despite evidence supporting that ‘seemingly unrelated impairments in a remote anatomical region may contribute to, or be associated with the patient’s primary complaint’.4–8

Further complicating clinical decision making are the deficiencies in current diagnostic processes. There have been variable descriptions of pain sources for LBP, including the hip joint,9 sacroiliac joint (SIJ),10–12 and even an unidentified pain source12 after a diagnostic work-up. In fact, up to 10% of patients receiving diagnostic work-up at a spine surgeon’s clinic still did not have a defined pain source.12 An additional 25% of these patients were found to have significant contributions from the hip or SIJ for their complaints of LBP.12 Additionally complicating the diagnostic process is the potential inability of diagnostic imaging to identify the pain source, influence prognosis, or affect treatment outcomes.13–16

Clinical examination is also an area of concern regarding assessing an individual’s function. The ‘art’ of the clinical examination has seemed to suffer in light of ever increasing demands on efficiency,17–19 dependency on technology,20 defensive medicine,17,18,21–26 assorted patient and physician-related factors,27 and perhaps indolence. The decline in the capacity of performance of a skilled clinical examination has occurred from an over reliance on clinical special tests, laboratory tests, and imaging.28 Deficiencies in history taking and physical examination have also been well illustrated.28 Dependency on technology can be both seductive and misleading, contributing to the demise in physical examination skills of physicians.20

Advantages and disadvantages of each component of the assessment of function were outlined in the first article of this series.29 Assessment of function, in our opinion, requires the clinician to continually assess and re-assess. Assessment of one’s true ability to function is therefore quite complicated, and potentially arduous. While a multi-level assessment approach has been described, not all levels are necessary for all patients.29 High-level athletes may require only the higher levels of assessment, whereas, other patients may require multiple levels of assessment over an extended period of time. Others may start at lower levels and then skip to higher levels of assessment. It is the responsibility of the clinician to determine the most appropriate levels of assessment. This is where we believe that the comprehensive nature of function assessment reaps rewards. In the following case report, we attempt to demonstrate a specific example of how this approach can be employed.

Patient Characteristics

The patient was a healthy 26-year-old male with medical diagnosis of low back and right hip pain. He denied any previous significant medical history. Prior to assessment, the patient described in this case had three superficial heat and ultrasound treatments, along with hip stretching exercises from another clinician without any improvement in symptoms.

Sports/work history

The patient, a high-level athlete, had participated in throwing the javelin for 10 years. At the time of injury, the patient was training for the Olympic trials in the upcoming year. The patient was also concurrently working for a shipping service in the late evening to support his training. Work requirements involved repetitive lifting of boxes up to 50 lbs off the floor onto a conveyor belt, walking long distances, and standing for up to 10 minutes in one position.

Injury history

His injury history was significant for previous low back and groin pain similar to current pain location about 3 years ago as a result of performing medicine ball throws. The pain at that time was more in the groin than low back. Modality and stretching treatments quickly resolved his pain at that time.

Examination

Onset of right lateral SIJ, groin, and LBP was ∼2 weeks prior to examination, and was due to performing 18-inch plyometric box jumps and landing awkwardly, predominantly on the right lower extremity. Initially the patient felt a sharp pinching pain, with an audible pop in what he perceived to be his right lateral hip.

Pain was worse with transitional movements (sit to stand, first steps of walking, etc.), in addition to an inability to perform any training/work duties. Sharp pain (7/10 at worst on a 0–10 pain scale) was primarily lateral to right SIJ and low back, while deep groin pain was primarily with sitting (especially in low chairs) and rated at 4/10. Best pain rating was 0/10 at rest. Patient was able to walk normally with pain level of 2/10 after initial painful 2–3 steps.

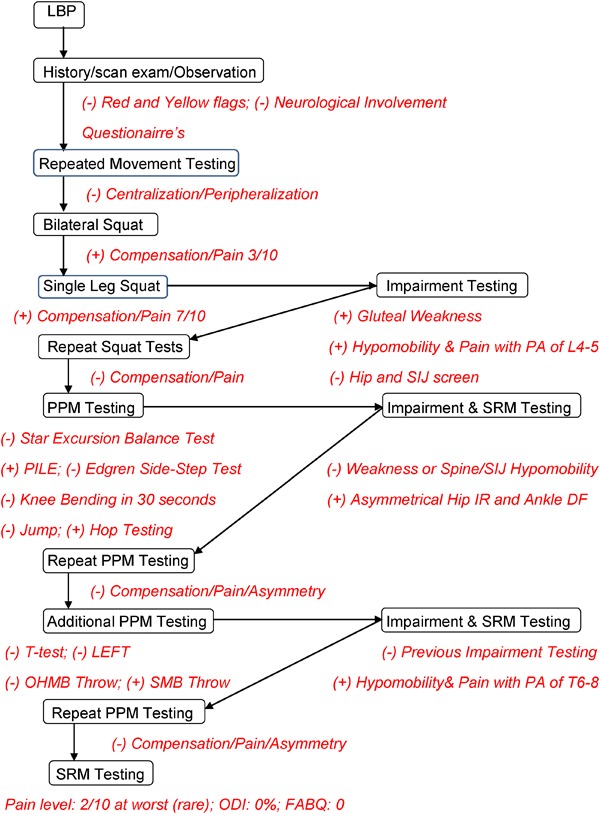

Multiple components of function were assessed during the patient’s rehabilitation (Table 1; Fig. 1). Diagnostic imaging was never practiced in this case once red flags and primary discogenic pathology was ruled out.30–39

Table 1. Summary of outcome measures.

| Measure | Initial visit | 2 weeks | 4 weeks | 6 months |

| Fear avoidance beliefs questionnaire | ||||

| Physical activity scale (0–24) | 12 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| Work scale (0–42) | 19 | 21 | 0 | 0 |

| Oswestry disability index (0–100%) | 42% | 36% | 8% | 0 |

| Pain intensity (at worst) | ||||

| Ordinal scale (0–10) | 7/10 | 4/10 | 2/10 | 0/10 |

| Pain intensity (at best) | ||||

| Ordinal scale (0–10) | 2/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 |

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of function assessment utilized in case. LBP, low back pain; PA, posterior–anterior joint play assessment; L4-5, lumbar 4 and 5 vertebrae; PPM, physical performance measure; SRM, self-report measure; PILE, progressive inertial lifting evaluation; SIJ, sacroiliac joint; IR, internal rotation; DF, dorsiflexion; LEFT, lower extremity functional test; OHMB, overhead medicine ball; SMB, side medicine ball; T6-8, thoracic 6 through 8 vertebrae; ODI, Oswestry disability index; FABQ, fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire.

Physical performance measures (PPMs), self-report measures (SRMs), and impairment testing methods were collaboratively employed dependent on previous examination findings. At each visit, the patient was asked to rate his pain on a 0–10 pain scale in which 0 reflected no pain and 10 was the worst pain imaginable. Additionally, an asterisk sign (particular movement/task that reproduced his pain) was utilized to determine his current status. All positive findings were re-examined after appropriate treatment. More complex PPMs were assessed once lower level PPMs were successfully completed.

The discovery of functional limitations with bilateral and single leg squat required impairment testing. Lumbar spine hypomobility and gluteal weakness was addressed as described below. Hip intra-articular pathology and SIJ were ruled out with negative findings on flexion–adduction–internal rotation testing,40 only one motion of hip joint restricted mobility,41 and a negative SIJ thrust test.42

Various PPMs were then employed to assess dynamic, multi-planar single-leg function (star excursion balance test and knee bending in 30 seconds) and quick lateral agility (Edgren side-step test). Assessment of all of these abilities was considered necessary since these movements are similar to throwing the javelin.43

Assessment of lifting ability [progressive inertial lifting evaluation (PILE) test] (Fig. 2) measured the patient’s readiness for return to employment. The PILE test was chosen since the movements required for successful completion closely represented the patient’s job duties. Once this PPM was passed, a return to light duty work, with a progressive return to previous job duties, was allowed.

Figure 2.

PILE testing. Reproduced with permission [reprinted, by permission from M Reiman and R Manske, 2009. Functional testing in human performance (Champaign, IL, Human Kinetics), 231. © Human Kinetics].

Limitations with PILE testing and hop testing were further clarified with impairment findings of asymmetrical hip internal rotation and ankle dorsiflexion range-of-motion on the involved right side. Once these limitations were corrected, repeat jump and hop testing were re-assessed. Serial assessment of these types of measures is suggested to ensure continued proper performance.44

Explosive throwing ability (overhead medicine ball throw and side medicine ball throw), agility/quickness (T-test), and anaerobic capacity (lower extremity functional test) were chosen as the demands of these PPMs were again similar to throwing the javelin.43

Re-assessment of side medicine ball throw testing was done after interventions addressing thoracic spine impairments were corrected. Pain-free performance of the side medicine ball throw, along with repeat testing of SRMs deemed the patient appropriate for discharge from formal therapy.

Clinical Impression

Functional performance testing was suggestive of musculoskeletal dysfunction without neurological, bio-psycho-social, or serious pathology involvement.

Intervention

The patient was seen for a total of six visits over a 4-week period prior to successful return to independent sport training. Several orthopedic manual therapy techniques were implemented to address the various impairments ascertained during the assorted levels of testing (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of OMT treatment utilized in case.

| OMT treatment | Limited PPM | Determined impairment |

| Lumbar spine side-lying gapping grade V thrust for two visits | • Pain with bilateral squat | • Limited right-side unilateral posterior–anterior joint mobility of L4-5 |

| • Pain worse with single-leg squat on involved right LE | ||

| Grade V long-axis thrust and grade IV posterior capsule mobilization to the right hip for three visits | • Hop testing elicited pain and asymmetry in distance jumped compared to non-involved side | • Limited hip internal rotation on involved right LE compared to non-involved side |

| • Pain with PILE test (initial lifting) (Fig. 2) | ||

| Talocrural joint grade V thrust for one visit | • Hop testing elicited pain and asymmetry in distance jumped compared to non-involved side | • Limited talocrural joint posterior glide mobility and pain with assessment |

| Grade V thrust thoracic spine vertebral levels 6 through 8 for two visits | • Asymmetry of distance thrown and pain with right rotation SMB throw | • Limited posterior–anterior joint mobility and pain at corresponding levels with joint play assessment |

Note: OMT, orthopedic manual therapy; PPM, physical performance measure; LE, lower extremity; L4-5, lumbar 4 and 5 vertebral level; PILE, progressive inertial lifting evaluation; SMB, side medicine ball.

Additional treatments during the rehabilitation program included gluteal and trunk stabilization training exercises, self-mobilization of posterior hip in quadruped, and anaerobic capacity training to limit deconditioning. Throughout the rehabilitation program, the patient was advised to maintain his conditioning level as per tolerance. Conditioning consisted of aquatic training and upper body ergometer early in rehabilitation sequence. Progression to weight training, running, jumping drills, and sports-specific training was integrated throughout the rehabilitation process dependent on re-assessment status.

Outcomes

SRMs, subjective reporting, and pain-free demonstration of throwing technique determined full release from professional care after six treatment sessions. The patient was able to return to a progressive, periodized sport training program with his coach at this time. The patient was recently seen for a 6-month follow-up. He had returned to normal training and job duties as prior to onset of symptoms without complaints (Table 1).

Discussion

This case describes the use of various components of function assessment. This assessment approach is highly reliant on the clinician’s diagnostic abilities. Multiple deficiencies have been documented with various aspects of clinical and technological examinations. Therefore, do we continue to focus our examinations on over-utilized and over-interpreted testing,13,45–51 as well as inadequate clinical testing52–54 procedures to assess the various impairments that a patient may have, or do we actually assess the entire patient? The deficiencies in these various testing methods only strengthen the support for clinicians to use their knowledge of proper movement and function in daily clinical practice. Continuous re-assessment, making use of various measures and clinical skills provides a much clearer picture of the patient’s true status compared to over-reliance on one specific assessment method. The assessment of function in this case report is strongly based on looking at multiple constructs in order to determine the concept of function.

Physical performance measures have traditionally been viewed as assessment methods appropriate only in later stages of rehabilitation. These PPMs have also customarily been categorized into one large assemblage of assessment methods. Rather than holding onto such customary philosophy regarding PPMs, it is offered that PPMs be utilized similar to other means of patient analysis. Of particular comparison would be special testing. The current literature provides us with judicious evidence supporting the use of some impairment tests as valuable screening or diagnostic methods. Unfortunately, as previously outlined, there are also several insufficient impairment tests. Additionally, there are very few tests that can be utilized for both screening and diagnostic means. Physical performance measures could serve similar or coexisting purposes with these tests.

Initial visit assessment was suggestive of musculoskeletal dysfunction with limited potential for serious spinal pathology, bio-psycho-social and discogenic/neurological involvement.30,36–39 The incidence of red flags in LBP is very rare.30,38 While a negative cluster of patient history variables essentially rules out sinister disorders with a sensitivity of 100%,39 the potential for fairly high false-positive rates does exist.30

Bio-psycho-social involvement has many ways to be measured. In our case, we chose the fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire (FABQ).31 The FABQ has been advocated as an appropriate instrument to identify patients with LBP who have elevated fear-avoidance beliefs and who may be at increased risk for prolonged disability.32–34 Our patient scored below an FABQ physical activity scale score indicative of ‘high’ fear-avoidance beliefs.31,35 Therefore, confident in a musculoskeletal diagnosis, we utilized a systematic, comprehensive examination scheme to determine the specific dysfunction(s).

Although no discriminative values exist, squat movements were utilized as screening tools in this case. Compensatory movements during squatting type activities have been demonstrated in subjects with LBP.55–57 Additionally, quantitative assessment of single-leg squat ability (level IV testing)29 for both lower extremity pathology58 and lumbopelvic stability59 has been substantiated. Our patient was able to perform bilateral squatting with minimal pain. Having the patient perform the same maneuver with bilaterally internally rotated lower extremities was also utilized to assimilate hip impingement test positioning.40 No change in symptoms in this position was interpreted as a component for the screening of intra-articular hip pathology. LBP was increased with single-leg squatting. Although not specific, this finding did lead to impairment testing.

Impairment testing (level II)29 of posterior to anterior mobility of L4-5 segment of the lumbar spine, negative hip screening (hip impingement40 and range-of-motion assessment),41 and negative SIJ provocation testing,42 combined with previous PPM findings, was a composite suggestion of right-side lumbar dysfunction versus lower extremity pathology. Joint mobility assessment of the spine has demonstrated marginal statistical value for detection of hypomobility alone.60–63 Pain accompanied with joint mobility assessment though has been demonstrated to be both reliable and valid.64–66 Screening out the other potential pain generators with a combination of PPMs and impairment testing methods was necessary due to the independent limitations of each assessment method.

Assessment of various components of sport-specific and work requirements involved several PPMs (star excursion balance test, Edgren side-step test, knee bending in 30 seconds, horizontal jump, hop testing, and the PILE test). Although these tests have all shown adequate levels of reliability, and have previously established normative values, their statistical value is limited in injured subjects.67 Several hop tests have demonstrated sensitive and specific values, but these are primarily limited to knee dysfunction. The PILE test has been questioned in regard to its clinical utility compared to other PPMs for trunk muscle endurance and lifting capacity,68 but it is the PPM that best approximated our patient’s work requirements. Additionally, most of these other PPMs were not challenging enough for our client at this stage of his rehabilitation.

During hop testing, the patient landed with medial collapse69 and pain on the right side. Impairment testing detected limited hip internal rotation and ankle dorsiflexion mobility on the involved right side.

Although reliability of various joint range-of-motion measures has been well established, joint mobility assessment of the lower extremity has come under recent scrutiny.70 Limitations discovered with PPMs (hop and PILE testing) in combination with findings of limited talocrural and hip internal rotation mobility afforded increased clinician confidence as compared to reliance on PPMs or impairment measure findings alone.

Levels IX and X testing29 (T-test, LEFT test, and medicine ball throws) was utilized to more closely reciprocate the specific demands of javelin throwing.43 Proper function of the lumbopelvic-hip complex has been suggested to contribute to higher rotational velocity in multi-segmental movements.71 Therefore, with improving status, it was deemed necessary to ascertain the patient’s ability to progress to independent training.

Since our patient was a power athlete, we needed to determine his ability to produce power in a manner similar to the sporting event that he would participate in. The overhead medicine ball throw has shown strong correlation with a previously established power index.72 The side medicine ball throw has demonstrated significant correlations with trunk rotation torque, and was therefore suggested as valuable assessment of trunk rotation power in male athletes.73 Thus, while findings of limited and painful joint mobility of the thoracic spine were valuable, these limitations should not be relied on to determine the patient’s ability to reciprocate his sport activity.

This approach of looking at the ‘big picture’ (task specific movement) to determine dysfunction is an advantage of PPMs. The use of PPMs in the early stages of the examination process can provide better screening utility. Using PPMs in later stages of the examination/rehabilitation process may prove better clinical utility as measures of correlation to the required sport or occupational task(s). Physical performance measures are not unlike any other testing method in that each test serves different purposes. Some PPMs are better at screening mechanisms, while others are more measures of high performance capability.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates the use of an integrated approach for the assessment of a high-level athlete with LBP and groin pain. This case focus was primarily on PPMs and impairment testing. The utilization of SRMs and bio-psycho-social measures was determined to be less impactful on the patient’s limits of function than they might be in other cases, especially in cases of chronic LBP. The greatest benefit of functional performance testing is its comprehensive, multi-directional flow of assessment that is continually adaptive to changes in the patient’s status.

References

- 1.Fogel GR, Esses SI. Hip spine syndrome: management of coexisting radiculopathy and arthritis of the lower extremity. Spine J. 2003;3:238–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abenhaim L, Rossignol M, Gobeille D, Bonvalot Y, Fines P, Scott S. The prognostic consequences in the making of the initial medical diagnosis of work-related back injuries. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20:791–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown MD, Gomez-Marin O, Brookfield KF, Li PS. Differential diagnosis of hip disease versus spine disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004:280–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Offierski CM, MacNab I. Hip-spine syndrome. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1983;8:316–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wainner RS, Whitman JM, Cleland JA, Flynn TW. Regional interdependence: a musculoskeletal examination model whose time has come. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37:658–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cleland JA, Childs JD, Fritz JM, Whitman JM, Eberhart SL. Development of a clinical prediction rule for guiding treatment of a subgroup of patients with neck pain: use of thoracic spine manipulation, exercise, and patient education. Phys Ther. 2007;87:9–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyles RE, Ritland BM, Miracle BM, Barclay DM, Faul MS, Moore JH, et al. The short-term effects of thoracic spine thrust manipulation on patients with shoulder impingement syndrome. Man Ther. 2009;14:375–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitman JM, Flynn TW, Childs JD, Wainner RS, Gill HE, Ryder MG, et al. A comparison between two physical therapy treatment programs for patients with lumbar spinal stenosis: a randomized clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:2541–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell B, McCrory P, Brukner P, O’Donnell J, Colson E, Howells R. Hip joint pathology: clinical presentation and correlation between magnetic resonance arthrography, ultrasound, and arthroscopic findings in 25 consecutive cases. Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13:152–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hodge JC, Bessette B. The incidence of sacroiliac joint disease in patients with low-back pain. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1999;50:321–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Bogduk N. The sacroiliac joint in chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20:31–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sembrano JN, Polly DW., Jr How often is low back pain not coming from the back? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:E27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borenstein DG, O’Mara JW, Jr, Boden SD, Lauerman WC, Jacobson A, Platenberg C, et al. The value of magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine to predict low-back pain in asymptomatic subjects: a seven-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83A:1306–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carragee E, Alamin T, Cheng I, Franklin T, Haak van denE, Hurwitz E. Are first-time episodes of serious LBP associated with new MRI findings? Spine J. 2006;6:624–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kleinstuck F, Dvorak J, Mannion AF. Are ‘structural abnormalities’ on magnetic resonance imaging a contraindication to the successful conservative treatment of chronic nonspecific low back pain? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:2250–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Modic MT, Obuchowski NA, Ross JS, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Grooff PN, Mazanec DJ, et al. Acute low back pain and radiculopathy: MR imaging findings and their prognostic role and effect on outcome. Radiology. 2005;237:597–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Espeland A, Baerheim A. Factors affecting general practitioners’ decisions about plain radiography for back pain: implications for classification of guideline barriers — a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2003;3:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ransohoff DF. Challenges and opportunities in evaluating diagnostic tests. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:1178–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shye D, Freeborn DK, Romeo J, Eraker S. Understanding physicians’ imaging test use in low back pain care: the role of focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 1998;10:83–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sahrmann S. Are physical therapists fulfilling their responsibilities as diagnosticians? J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2005;35:556–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith-Bindman R, McCulloch CE, Ding A, Quale C, Chu PW. Diagnostic imaging rates for head injury in the ED and states’ medical malpractice tort reforms. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29:656–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz DA, Williams GC, Brown RL, Aufderheide TP, Bogner M, Rahko PS, et al. Emergency physicians' fear of malpractice in evaluating patients with possible acute cardiac ischemia. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46:525–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrier ER, Reschovsky JD, Mello MM, Mayrell RC, Katz D. Physicians’ fears of malpractice lawsuits are not assuaged by tort reforms. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:1585–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hendee WR, Becker GJ, Borgstede JP, Bosma J, Casarella WJ, Erickson BA, et al. Addressing overutilization in medical imaging. Radiology. 2010;257:240–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeKay ML, Asch DA. Is the defensive use of diagnostic tests good for patients, or bad? Med Decis Making. 1998;18:19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, DesRoches CM, Peugh J, Zapert K, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA. 2005;293:2609–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whiting P, Toerien M, de Salis I, Sterne JA, Dieppe P, Egger M, et al. A review identifies and classifies reasons for ordering diagnostic tests. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:981–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feddock CA. The lost art of clinical skills. Am J Med. 2007;120:374–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reiman MP, Manske RC. The assessment of function, Part 1 — How is it measured? A clinical perspective. J Man Manip Ther. 2011;19:91–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Herbert RD, Cumming RG, Bleasel J, et al. Prevalence of and screening for serious spinal pathology in patients presenting to primary care settings with acute low back pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:3072–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, Somerville D, Main CJ. A Fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain. 1993;52:157–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fritz JM, George SZ, Delitto A. The role of fear-avoidance beliefs in acute low back pain: relationships with current and future disability and work status. Pain. 2001;94:7–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vlaeyen JW, Linton SJ. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain. 2000;85:317–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waddell G, Somerville D, Henderson I, Newton M. Objective clinical evaluation of physical impairment in chronic low back pain. Spine. 1992;17:617–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burton AK, Waddell G, Tillotson KM, Summerton N. Information and advice to patients with back pain can have a positive effect. A randomized controlled trial of a novel educational booklet in primary care. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24:2484–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laslett M, Oberg B, Aprill CN, McDonald B. Centralization as a predictor of provocation discography results in chronic low back pain, and the influence of disability and distress on diagnostic power. Spine J. 2005;5:370–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berthelot JM, Delecrin J, Maugars Y, Passuti N. Contribution of centralization phenomenon to the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of diskogenic low back pain. Joint Bone Spine. 2007;74:319–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lurie JD. What diagnostic tests are useful for low back pain? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2005;19:557–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jarvik JG, Deyo RA. Imaging of lumbar intervertebral disk degeneration and aging, excluding disk herniations. Radiol Clin North Am 2000;38:1255–66 vi [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sink EL, Gralla J, Ryba A, Dayton M. Clinical presentation of femoroacetabular impingement in adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008;28:806–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Birrell F, Croft P, Cooper C, Hosie G, Macfarlane G, Silman A. Predicting radiographic hip osteoarthritis from range of movement. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2001;40:506–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laslett M, Aprill CN, McDonald B, Young SB. Diagnosis of sacroiliac joint pain: validity of individual provocation tests and composites of tests. Man Ther. 2005;10:207–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu H, Leigh S, Yu B. Sequences of upper and lower extremity motions in javelin throwing. J Sports Sci. 2010;28:1459–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McElveen MT, Riemann BL, Davies GJ. Bilateral comparison of propulsion mechanics during single-leg vertical jumping. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24:375–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kent DL, Haynor DR, Larson EB, Deyo RA. Diagnosis of lumbar spinal stenosis in adults: a metaanalysis of the accuracy of CT, MR, and myelography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;158:1135–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jarvik JG, Deyo RA. Diagnostic evaluation of low back pain with emphasis on imaging. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:586–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boden SD, Davis DO, Dina TS, Patronas NJ, Wiesel SW. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:403–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haig AJ, Geisser ME, Tong HC, Yamakawa KS, Quint DJ, Hoff JT, et al. Electromyographic and magnetic resonance imaging to predict lumbar stenosis, low-back pain, and no back symptoms. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:358–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, Modic MT, Malkasian D, Ross JS. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:69–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maus T. Imaging the back pain patient. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2010;21:725–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saal JS. General principles of diagnostic testing as related to painful lumbar spine disorders: a critical appraisal of current diagnostic techniques. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:2538–45; discussion 2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Windt van derDA, Simons E, Riphagen II, Ammendolia C, Verhagen AP, Laslett M, et al. Physical examination for lumbar radiculopathy due to disc herniation in patients with low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(2):CD007431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cook C, Hegedus E. Diagnostic utility of clinical tests for spinal dysfunction. Man Ther. 2011;16:21–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Graaf I, Prak A, Bierma-Zeinstra S, Thomas S, Peul W, Koes B. Diagnosis of lumbar spinal stenosis: a systematic review of the accuracy of diagnostic tests. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:1168–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shum GL, Crosbie J, Lee RY. Three-dimensional kinetics of the lumbar spine and hips in low back pain patients during sit-to-stand and stand-to-sit. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:E211–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shum GL, Crosbie J, Lee RY. Symptomatic and asymptomatic movement coordination of the lumbar spine and hip during an everyday activity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:E697–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shum GL, Crosbie J, Lee RY. Effect of low back pain on the kinematics and joint coordination of the lumbar spine and hip during sit-to-stand and stand-to-sit. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:1998–2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Crossley KM, Zhang WJ, Schache AG, Bryant A, Cowan SM. Performance on the single-leg squat task indicates hip abductor muscle function. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:866–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Perrott M, Cook J, Pizzari T. Clinical rating of poor lumbo-pelvic stability is associated with quantifiable, distinct movement patterns. J Sci Med Sport 2010;12(Supplement 2):E6 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anson E, Cook C, Comacho C, Gwilliam B, Karakostas T. The use of education in the improvement of finding R1 in the lumbar spine. J Man Manip Ther. 2003;11:204–12 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maher CG, Simmonds M, Adams R. Therapists’ conceptualization and characterization of the clinical concept of spinal stiffness. Phys Ther. 1998;78:289–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cook C, Turney L, Miles A, Ramirez L, Karakostas T. Predictive factors in poor inter-rater reliability among physical therapists. J Man Manip Ther. 2002;10:200–5 [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Trijffel E, Anderegg Q, Bossuyt PM, Lucas C. Inter-examiner reliability of passive assessment of intervertebral motion in the cervical and lumbar spine: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2005;10:256–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jull G, Bogduk N, Marsland A. The accuracy of manual diagnosis for cervical zygapophysial joint pain syndromes. Med J Aust. 1988;148:233–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jull G, Treleaven J, Verace G. Manual examination: Is pain provocation a major cue for spinal dysfunction? Aust J Physiother. 1994;40:159–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dickey JP, Pierrynowski MR, Bednar DA, Yang SX. Relationship between pain and vertebral motion in chronic low-back pain subjects. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2002;17:345–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reiman MP, Manske RC. Functional testing in human performance. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smeets RJ, Hijdra HJ, Kester AD, Hitters MW, Knottnerus JA. The usability of six physical performance tasks in a rehabilitation population with chronic low back pain. Clin Rehabil. 2006;20:989–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Powers CM. The influence of altered lower-extremity kinematics on patellofemoral joint dysfunction: a theoretical perspective. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33:639–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.van Trijffel E, van de Pol RJ, Oostendorp RA, Lucas C. Inter-rater reliability for measurement of passive physiological movements in lower extremity joints is generally low: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2010;56:223–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Saeterbakken AH, Tillaar van denR, Seiler S. Effect of core stability training on throwing velocity in female handball players. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25:712–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stockbrugger BA, Haennel RG. Contributing factors to performance of a medicine ball explosive power test: a comparison between jump and nonjump athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2003;17:768–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ikeda Y, Kijima K, Kawabata K, Fuchimoto T, Ito A. Relationship between side medicine-ball throw performance and physical ability for male and female athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2007;99:47–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]