Abstract

Anatomical, physiological, and lesion data implicate multiple cortical regions in the complex experience of pain. These regions include primary and secondary somatosensory cortices, anterior cingulate cortex, insular cortex, and regions of the frontal cortex. Nevertheless, the role of different cortical areas in pain processing is controversial, particularly that of primary somatosensory cortex (S1). Human brain-imaging studies do not consistently reveal pain-related activation of S1, and older studies of cortical lesions and cortical stimulation in humans did not uncover a clear role of S1 in the pain experience. Whereas studies from a number of laboratories show that S1 is activated during the presentation of noxious stimuli as well as in association with some pathological pain states, others do not report such activation. Several factors may contribute to the different results among studies. First, we have evidence demonstrating that S1 activation is highly modulated by cognitive factors that alter pain perception, including attention and previous experience. Second, the precise somatotopic organization of S1 may lead to small focal activations, which are degraded by sulcal anatomical variability when averaging data across subjects. Third, the probable mixed excitatory and inhibitory effects of nociceptive input to S1 could be disparately represented in different experimental paradigms. Finally, statistical considerations are important in interpreting negative findings in S1. We conclude that, when these factors are taken into account, the bulk of the evidence now strongly supports a prominent and highly modulated role for S1 cortex in the sensory aspects of pain, including localization and discrimination of pain intensity.

The role of primary somatosensory cortex (S1) in pain perception has long been in dispute. In the early 20th century, Head and Holmes (1) observed that patients with longstanding cortical lesions did not show deficits in pain perception. Similarly, Penfield and Boldrey (2), based on studies of electrical stimulation of patients’ exposed cerebral cortices during epilepsy surgery, concluded that pain probably has little or no cortical representation. In more recent studies of S1 cortex in monkeys, single-cell recordings in both anesthetized (3) and awake (4) monkeys revealed so few nociceptive neurons that their functional significance was uncertain.

Other evidence suggests that S1 cortex may indeed play an important role in pain perception. Despite the lack of profound deficits in pain perception after widespread cortical lesions, patients do show at least transient deficits following cortical lesions (1, 5). Furthermore, Young and Blume (6) have reported that some patients with epileptic foci involving S1 cortex experience painful seizures. Anatomical evidence from primates demonstrates that regions of thalamus containing nociceptive neurons project to S1 cortex (7–9), thus providing the possible framework necessary to support the processing of nociceptive information within S1. Additionally, despite the small numbers of nociceptive neurons observed in monkey S1 cortex, their responses parallel pain perception in humans (10, 11). For example, by using optical imaging and neuronal recording techniques, Tommerdahl et al. (11) showed that nociceptive activity in area 3a of S1 cortex exhibited slow temporal summation and poststimulus response persistence after repeated cutaneous heat stimulation, which parallel perceptual consequences of the stimulation in humans. Finally, bilateral ablation of S1 cortex in monkeys disrupts their ability to discriminate intensities of noxious heat (D. R. Kenshalo, Jr., D. A. Thomas, and R. Dubner, unpublished observations).

Findings from human brain imaging studies have produced inconsistent results pertaining to the role of S1 cortex in pain perception. The first three modern brain imaging studies of pain, published in the early 1990s, produced vastly different results in terms of S1 cortex. By using positron emission tomography (PET) and repeated 5-sec heat stimuli presented to six spots on the arm, Talbot et al. (12) found a significant activation focus in S1 cortex contralateral to the stimulated arm. By using similar heat stimuli, but repetitively presented to a single spot on the dorsal hand, Jones et al. (13) failed to observe significant activation in S1 cortex. Finally, by using single photon-emission computed tomography, Apkarian et al. (14) found that submerging the fingers in hot water for 3 minutes led to a decrease in S1 activity.

Jones and colleagues (15, 16) postulated that the experimental procedures used by Talbot et al., particularly moving the stimulus among six spots during the scans, differentially direct more attention to the pain stimulus than to the control stimulus, and thus produce an attention-related modulation of S1 cortical activity. They further postulated that the presence or absence of pain, itself, is probably not a main determinant of S1 activation. More recent studies support the idea that attention can significantly modulate pain-evoked S1 activity, but little evidence supports the premise that pain is not a major determinant of S1 activity during painful stimulation.

Table 1 shows the methods and results of a number of human brain imaging studies of pain, by using PET, single photon-emission computed tomography, functional MRI, and magnetoencephalographic imaging. In the various studies, pain stimuli include phasic and tonic heat, cold, chemical irritants, electric shock, ischemia, visceral distension, headache, and neuropathic pain. As can be seen in Table 1, there is little consistency among the studies as to whether S1 is activated by pain. Some studies involving thermal, chemical, or electrical stimulation reveal S1 activation, whereas others using similar stimuli do not. Several factors that may contribute to these differential results include (i) influences of cognitive modulation in S1 activity; (ii) averaging-related degradation of the signal because of variability of sulcal anatomy; (iii) a possible combination of excitatory and inhibitory effects of nociceptive input to S1; and (iv) differences in statistical analyses and power.

Table 1.

Methods and results of brain imaging studies

| Study | Ref. | Modality | Subject | n | Stimulation device | Stimulation | S1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Talbot et al. | 12 | PET H215O | Healthy | 8 | Thermode 1 cm2 | 42, 47–48°C | Yes |

| Jones et al. | 13 | PET15CO2 | Healthy | 6 | Thermode 2.5 cm × 5.0 cm | 36.1, 41.3, and 46.4°C | No |

| Apkarian et al. | 14 | SPECT | Healthy | — | Water bath | Moderate heat pain | Inhibition |

| Crawford et al. | 24 | PET131Xe | Healthy | 11 | Tourniquet | Ischemia | Yes |

| Coghill et al. | 25 | PET H215O | Healthy | 9 | Thermode, 1 cm2 | 34, 47–48°C | Yes |

| Di Piero et al. | 26 | SPET 133Xn | Healthy | 7 | Water bath | Cold pressor test | Yes |

| Derbyshire et al. | 27 | PET H215O | Facial pain | 6 | Thermode | Ramp, 25–43°C | No |

| Healthy | 7 | ||||||

| Rosen et al. | 28 | PET H215O | Angina pectoris | 12 | Dobutamine infusion | Angina | No |

| Hsieh et al. | 29 | PET H215O | Neuropathic | 8 | None | Spontaneous pain | No |

| Hsieh et al. | 30 | PET H215O | Healthy | 4 | Intracutaneous injection | Ethanol | Yes |

| Davis et al. | 31 | fMRI | Healthy | 9 | Electrical nerve stimulator | Median nerve, 50 Hz | Yes |

| Weiller et al. | 32 | PET H215O | Migraine patients | 9 | None | Spontaneous migraine | No |

| Howland et al. | 33 | MEG | Healthy | 5 | Electrical nerve stimulator | Electric finger shock | Yes |

| Kitamura et al. | 34 | MEG | Healthy | 5 | Electrical nerve stimulator | Electric finger shock | Yes |

| Craig et al. | 35 | PET H215O | Healthy | 11 | Thermal grill | Bars 20 and 40°C | Yes |

| Casey et al. | 36 | PET H215O | Healthy | 9 | Thermode | 40 and 50°C | Yes |

| Casey et al. | 36 | PET H215O | Healthy | 9 | Thermode | 6, 20°C | Yes |

| Hsieh et al. | 37 | PET H215O | Cluster headache | 7 | Sublinguial nitroglycerin | Headache | No |

| Andersson et al. | 21 | PET H215O | Healthy | 6 | Capsaicin | Intracutaneous | Yes |

| Antognini et al. | 38 | fMRI | Healthy | 5 | Electrical stimulator | Electric hand shock | Yes |

| Aziz et al. | 39 | PET H215O | Healthy | 8 | Balloon | Esophageal distension | Yes |

| Cluster headache | 7 | ||||||

| DiPiero et al. | 40 | SPECT | Healthy | 12 | Water bath | Cold pressor | Yes |

| Rainville et al. | 17 | PET H215O | Healthy | 11 | Water bath | 35, ≈47°C | Yes |

| Silverman et al. | 41 | PET H215O | Healthy | 6 | Balloon | Rectal distension | No |

| Svensson et al. | 42 | PET H215O | Healthy | 11 | CO2 laser | Cutaneous | Yes, ns |

| Svensson et al. | 43 | PET H215O | Healthy | 11 | Electrical stimulator | Intramuscular | Yes, ns |

| Xu et al. | 44 | PET H215O | Healthy | 6 | CO2 laser | Cutaneous | Yes |

| Binkofski et al. | 45 | fMRI | Healthy | 5 | Balloon | Esophageal distension | Yes |

| Derbyshire et al. | 46 | PET H215O | Healthy | 6 | Thermode | Ramp, 25–43°C | No |

| Iadarola et al. | 47 | PET H215O | Healthy | — | Capsaicin | Subcutaneous arm | No |

| May et al. | 48 | PET H215O | Healthy | 7 | Capsaicin | Subcutaneous forehead | No |

| Oshiro et al. | 49 | fMRI | Healthy | 6 | Electrical stimulator | Finger, 8 Hz | Yes |

| Paulson et al. | 50 | PET H215O | Healthy | 10 | Thermode, 254 mm2 | 40 & 50°C | No |

ns, not significant; SPECT, single photon-emission computed tomography; fMRI, functional MRI; MEG, magnetoencephalographic imaging.

Cognitive Modulation of S1 Activity.

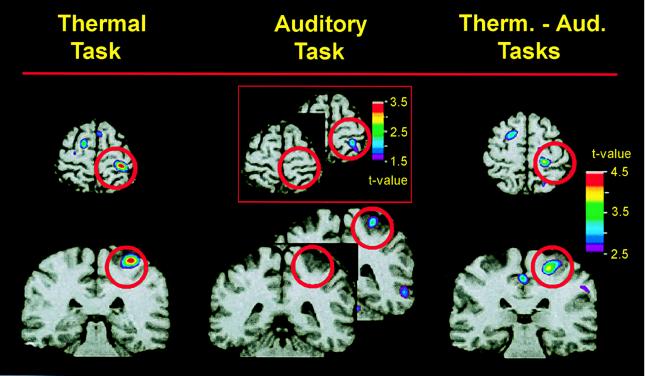

As proposed by Jones and colleagues (15, 16), S1 pain-related activation is highly modulated by cognitive factors that alter pain perception, including attention and previous experience. In our laboratory, we have shown that when the subject’s attention is directed away from a painful stimulus, the activity of S1 cortex is dramatically reduced (B.C., P. Rainville, T. Paus, G.H.D., and M.C.B., unpublished observations). Fig. 1 shows the results of this study, in which we used PET H215O bolus methods to measure regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) in nine subjects while they discriminated changes in thermal intensity or auditory frequency. During all scans, concurrent sequences of tones and contact heat stimuli (pain, 46.5–48.5°C or warm, 32–38°C on the left arm) were presented. After each scan, subjects used a 100-mm visual analogue scale to rate the perceived level of pain associated with the thermal stimuli. Statistical brain maps of pain-related activity, i.e., rCBF during the pain condition minus rCBF during the nonpainful warm condition, were obtained. Pain intensity was rated higher in the thermal than in the auditory task (50.4 vs. 41.4, P = 0.01), indicating that pain perception was modulated by the attentional demands of the discrimination tasks. Likewise, whereas in the thermal task there was a significant pain-related rCBF increase within S1 (t = 4.42, P < 0.01), there was no significant change in pain-related rCBF within S1 during the auditory task (Fig. 1). A direct comparison of pain-related S1 activity during the pain and auditory tasks showed that pain-evoked rCBF was significantly larger in the thermal than in the auditory task (t = 3.92; P < 0.01). In this experiment, the behavioral task used to direct attention toward the thermal stimuli involved the detection of a small change in the intensity of the heat stimulus. This task probably served to specifically direct the subjects’ attention to sensory aspects of the pain, rather than to the unpleasantness or suffering.

Figure 1.

Pain-related activity when attention is directed to the painful heat stimulus (Left) or to an auditory stimulus (Center) is revealed by subtracting PET data recorded when a warm stimulus (32–38°C) was presented from those recorded when a painfully hot stimulus (46.5–48.5°C) was presented during each attentional state. Differences in pain-related activity during the two attentional conditions are revealed (Right) by subtracting PET data recorded during the auditory task from that recorded during the heat-discrimination task (using only painful stimulus trials—46.5–48.5°C). PET data, averaged across nine subjects, are illustrated against an MRI from one subject. Horizontal and coronal slices through S1 are centered at the activation peaks. Red circles surround the region of S1. Whereas there was a significant activation of S1 when subjects attended to the painful stimulus (Left), there was no significant activation when subjects attended to the auditory stimulus (Center). However, there was a subsignificant activation in S1 during the auditory task, as shown in the Inset. The direct comparison of pain in the two attentional conditions (Right) shows a significant difference in pain-related S1 activity during the two attentional states.

Other data from our laboratory also support the idea that attention to sensory aspects of the pain experience can alter S1 activity. By using hypnosis, we found that suggestions specifically directed toward increasing or decreasing the perceived intensity of the burning pain sensation produced by submerging a subject’s hand in painfully hot water modulated pain-related activity in S1 (R.K.H., P. Rainville, G.H.D., and M.C.B., unpublished observations). In contrast, suggestions directed toward changing the unpleasantness of the pain had no effect on pain-related activity in S1, but produced instead a robust modulation of activity in anterior cingulate cortex directly correlated with the subjects’ perception of unpleasantness (ANCOVA, P = 0.005) (17).

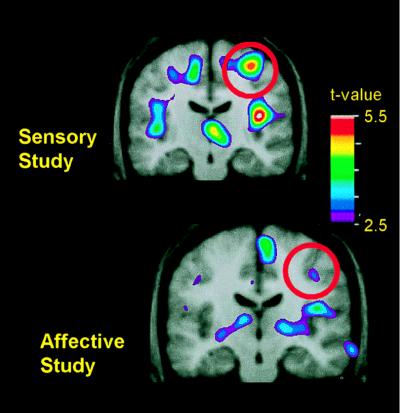

In these hypnosis experiments, we also found evidence that experience with the hypnotic suggestions may have produced long-term changes in the subjects’ neural processing of pain. At least a week before participating in a PET scanning session, all subjects received the same hypnotic induction, suggestions, and painful stimuli that were to be used during the scanning experiment. In subsequent PET sessions, two scans using the painful heat and two using the nonpainful warm control stimulus were performed before the subjects underwent hypnotic induction and suggestions. During these four scans, the subjects were simply instructed to relax and attend to the thermal stimulus—a control situation for identifying regions that could be examined for modulation related to hypnotic suggestions given in subsequent scans. Although subjects in the two hypnosis experiments produced similar ratings of pain intensity and unpleasantness during these control scans, those previously trained to attend to the intensity of the painful stimuli showed substantially greater pain-related activity in S1 than did those who had been trained to attend to the unpleasantness of those stimuli [Fig. 2 Upper (t = 5.05); Lower (17) (t = 3.01)].

Figure 2.

Changes in pain-related activity associated with previous hypnotic training by using suggestions for modulating pain sensation (Upper) or pain unpleasantness (Lower). Both images represent data from control scans, in which no hypnotic suggestions were given. Each image represents the subtraction of PET data recorded when the hand was submerged in thermally neutral water (35°C) from data recorded when the hand was submerged in painfully hot water (47°C). PET data were averaged across 10 experimental sessions in the sensory study (Upper) and, in a different group of subjects, 11 experimental sessions in the affective study (Lower). The PET data are illustrated against the average MRI for that subject group. Coronal slices through S1 are centered at the activation peaks, and red circles surround the region of S1.

Attentional modulation within S1 cortex is not restricted to pain-related activity. Other investigators have found that rCBF in S1, evoked by tactile stimuli, is reduced when subjects attend to another stimulus modality (18). Similarly, neuronal recordings in S1 cortex of trained monkeys reveal low-threshold neurons whose activity is enhanced by attention to the tactile stimulus (19, 20). Despite the extensive nature of attentional modulation of S1 activity, there is little evidence that attention activates S1 neurons without the concurrent presence of sensory-evoked activation. Anticipation of a painful stimulus has been shown to produce decreases in S1 rCBF (51) rather than increases in rCBF that would reflect excitatory neuronal activity.

Variability of S1 Sulcal Anatomy.

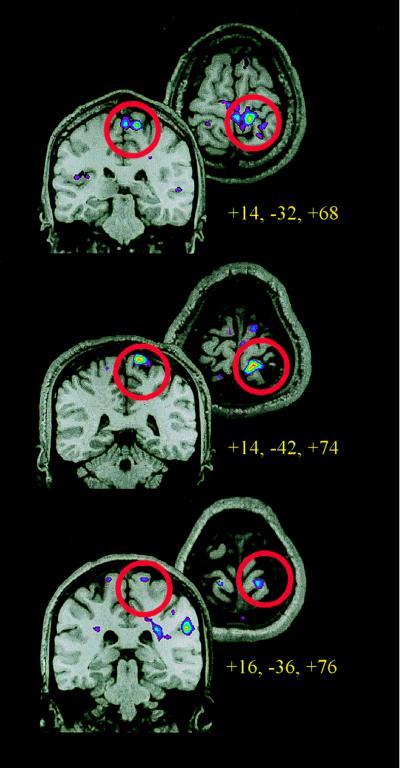

Both monkey and human data indicate that nociceptive activity in S1 cortex is somatotopically organized. Neuronal recording studies in monkeys show a somatotopic organization for nociceptive neurons similar to that observed for low-threshold cells (3). Similarly, by using PET to measure rCBF and capsaicin as a specific nociceptive stimulus, Andersson et al. (21) found distinct activation sites related to foot and hand pain, consistent with the known topographic organization of cutaneous receptive fields within S1. The somatotopic organization of S1 cortex probably results in a small focal activation evoked by a localized pain stimulus. Such focal activation is more easily observed with single-subject functional MRI studies than in PET studies involving a number of subjects and data smoothing. Fig. 3 shows the focal activation produced in S1 cortex of three individual subjects when the leg was stimulated with noxious heat (B.H., J.-I.C., B. Pike, G.H.D., and M.C.B., unpublished observations). The images show regions activated during stimulation with painful heat, as compared with that observed during nonpainful warm. Fig. 3 also shows that the pain-related S1 activation sites, although on the posterior bank of the central sulcus in all subjects, varied in terms of their stereotaxic coordinates, suggesting small intersubject differences in the localization of pain-related activity. This anatomical variability, although not of a large magnitude, degrades a focal signal when data are averaged across subjects. Thus, because of the somatotopically organized focal activation observed in S1, the rCBF signal arising from this area may be particularly susceptible to degradation when averaging data.

Figure 3.

Functional MRI data from three subjects, using a 1.5-T scanner and standard head coil. Each horizontal and coronal image represents the anatomical and functional data from a single subject during one session, which included a high-resolution anatomical scan and five to eight runs of 120 whole-brain functional MRI scans (10–13) 7-mm slices acquired at 3-sec intervals. Thermal stimuli were applied to the left calf on separate runs. Thermal runs consisted of 9 s alternating cycles of rest, painful (45–46°C), rest, and neutral (35–36°C) stimulation by using a 9 cm2 thermode. Activation maps were generated by using Spearman’s rank order correlation, comparing painful to neutral heat. The coronal and horizontal slices through S1 are centered at the activation peaks, and red circles surround the region of S1.

Inhibitory Effects of Noxious Stimuli in S1 activity.

Tommerdahl et al. (11) found in monkey S1 cortex that the presence of noxious heat reduced the intrinsic optical-imaging signal evoked by low-threshold mechanical stimulation of the skin. These data are consistent with the findings of Apkarian et al. (14), which showed a decrease in blood flow to S1 cortex in human subjects during the presentation of a tonic heat stimulus. Consonant with the idea that noxious stimulation produces inhibition of tactile sensitivity in S1 cortex are psychophysical data showing that the presence of pain reduces tactile perception (22).

Other evidence suggests that the inhibition of S1 tactile activity by noxious stimuli may take place at lower levels of the neuraxis rather than through a direct inhibitory influence at the level of S1. In awake monkeys, the spontaneous activity of low-threshold neurons in the ventroposterior thalamus is inhibited by topical application of capsaicin, which specifically excites C fibers (C.-C. Chen and M.C.B., unpublished observations). Similarly, capsaicin sometimes reduces the responses of spinothalamic tract neurons to noxious heat stimulation (23). Thus, when a painful stimulus is presented in a human brain imaging study, the net effect of exciting some neurons and inhibiting the spontaneous activity of others could have different effects on rCBF (as measured by PET) or on venous blood oxygenation (as measured by functional MRI), depending on such variables as timing, duration, location, and intensity of the painful stimulus.

Procedural and Analytical Differences in Studies.

In human brain imaging studies, many procedural variables can influence the resultant data. Analytical techniques are not standardized across laboratories or across imaging methods. For example, different approaches are used to compare stimulation conditions, including subtraction and regression comparisons across scans. Instructions to the subjects, which can influence the cognitive state, vary among studies, as does the timing of stimulus variables. The statistical analyses, including methods for calculating variance and assumptions about the nature of the data, also differ among laboratories. Although all analyses rely on some type of statistical determination of significance, the method of accounting for multiple comparisons varies, and thus the criteria for identifying an activation as significant are not uniform across studies. Finally, the power of any statistical test is influenced by the number of subjects studied, which is another factor that varies greatly among studies.

As with any statistical test, the interpretation of negative results must be performed with caution. Thus, it would appear more fruitful to identify regions that show activation across a number of pain studies than to rely on the data of any one study in isolation. Despite the wide methodological and analytical variation in human brain imaging studies of pain, there is surprising consistency in the activation of a number of brain regions, including anterior cingulate and insular cortices. Although the observation of pain-related activation in S1 is somewhat less consistent, the fact that at least half of the human brain imaging studies have identified significant activation of this region when subjects perceive pain suggests that S1 has a significant role in nociceptive processing.

What Is the Role of S1 in Pain Processing?

Anatomical, neurophysiological, and imaging data confirm a role of S1 cortex in pain processing. Overall, the findings support the traditional view that S1 is primarily involved in discriminative aspects of somatic sensation and extends this view to include discriminative aspects of somatic stimulation that is potentially tissue-damaging, e.g., painful. Single neurons in monkey S1 code stimulus intensity, location, and duration, and their activity correlates with human perception. Human imaging studies show activation of S1 by a range of noxious stimuli, including capsaicin, which selectively activates C fibers. These studies also confirm the somatotopic organization of S1 pain responses, thus supporting the role of S1 in pain localization. Other imaging data that implicate S1 in the sensory aspect of pain perception are findings that S1 activation is modulated by cognitive manipulations that alter perceived pain intensity but not by manipulations that alter unpleasantness, independent of pain intensity. Nevertheless, despite the probable role of S1 in the encoding of the various sensory features of pain, a considerable amount of evidence suggests that nociceptive input to S1 may also serve to modulate tactile perception, described by Apkarian et al. as a “touch gate” (22). Thus, S1 cortex may be involved in both perception and modulation of both painful and nonpainful somatosensory sensations.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our appreciation to Ms. Francine Bélanger for her help in preparing this manuscript and to Dr. Pierre Rainville for his intellectual and technical contributions to these studies. Imaging studies were performed at the Montreal Neurological Institute with the help and expertise of the its staff. This research is supported by operating grants from the Canadian Medical Research Council awarded to M.C.B. and to G.H.D.

ABBREVIATIONS

- S1

primary somatosensory cortex

- PET

positron emission tomography

- rCBF

regional cerebral blood flow

References

- 1.Head H, Holmes G. Brain. 1911;34:102–254. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penfield W, Boldrey E. Brain. 1937;60:389–443. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kenshalo D R, Jr, Isensee O. J Neurophysiol. 1983;50:1479–1496. doi: 10.1152/jn.1983.50.6.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kenshalo D R, Jr, Chudler E H, Anton F, Dubner R. Brain Res. 1988;454:378–382. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90841-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White J C, Sweet W H. Pain and the Neurosurgeon: A Forty-Year Experience. Springfield, IL: Thomas; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young G B, Blume W T. Brain. 1983;106:537–554. doi: 10.1093/brain/106.3.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gingold S I, Greenspan J D, Apkarian A V. J Comp Neurol. 1991;308:467–490. doi: 10.1002/cne.903080312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kenshalo D R, Jr, Giesler G J, Leonard R B, Willis W D. J Neurophysiol. 1980;43:1594–1614. doi: 10.1152/jn.1980.43.6.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rausell E, Jones E G. J Neurosci. 1991;11:210–225. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-01-00210.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chudler E H, Anton F, Dubner R, Kenshalo D R., Jr J Neurophysiol. 1990;63:559–569. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.63.3.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tommerdahl M, Delemos K A, Vierck C J, Jr, Favorov O V, Whitsel B L. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:2662–2670. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.6.2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talbot J D, Marrett S, Evans A C, Meyer E, Bushnell M C, Duncan G H. Science. 1991;251:1355–1358. doi: 10.1126/science.2003220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones A K P, Brown W D, Friston K J, Qi L Y, Frackowiak R S J. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 1991;244:39–44. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1991.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Apkarian A V, Stea R A, Manglos S H, Szeverenyi N M, King R B, Thomas F D. Neurosci Lett. 1992;140:141–147. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90088-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones A K P, Friston K, Frackowiak R S J. Science. 1992;255:215–215. doi: 10.1126/science.1553549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones A K P, Derbyshire S W G. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996;55:411–420. doi: 10.1136/ard.55.7.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rainville P, Duncan G H, Price D D, Carrier B, Bushnell M C. Science. 1997;227:968–971. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer E, Ferguson S G, Zatorre R J, Alivisatos B, Marrett S, Evans A C, Hakim A M. Ann Neurol. 1991;29:440–443. doi: 10.1002/ana.410290418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hyvärinen J, Poranen A, Jokinen Y. J Neurophysiol. 1980;43:870–882. doi: 10.1152/jn.1980.43.4.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poranen A, Hyvärinen J. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1982;53:535–537. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(82)90065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersson J L R, Lilja A, Hartvig P, Långström B, Gordh T, Handwerker H, Torebjörk E. Exp Brain Res. 1997;117:192–199. doi: 10.1007/s002210050215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Apkarian A V, Stea R A, Bolanowski S J. Somatosens Mot Res. 1994;11:259–267. doi: 10.3109/08990229409051393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dougherty P M, Schwartz A, Lenz F A. Neuroscience. 1998;90:1377–1392. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00551-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crawford H J, Gur R C, Skolnick B, Gur R E, Benson D M. Int J Psychophysiol. 1993;15:181–195. doi: 10.1016/0167-8760(93)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coghill R C, Talbot J D, Evans A C, Meyer E, Gjedde A, Bushnell M C, Duncan G H. J Neurosci. 1994;14:4095–4108. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-07-04095.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Piero V, Ferracuti S, Sabatini U, Pantano P, Cruccu G, Lenzi G L. Pain. 1994;56:167–173. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Derbyshire S W G, Jones A K P, Devani P, Friston K J, Feinmann C, Harris M, Pearce S, Watson J D G, Frackowiak R S J. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:1166–1172. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.10.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosen S D, Paulesu E, Frith C D, Frackowiak R S J, Davies G J, Jones T, Camici P G. Lancet. 1994;344:147–150. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92755-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsieh J C, Belfrage M, Stone-Elander S, Hansson P, Ingvar M. Pain. 1995;63:225–236. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00048-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsieh J C, Ståhle-Bäckdahl M, Hägermark, Stone-Elander S, Rosenquist G, Ingvar M. Pain. 1995;64:303–314. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis K D, Wood M L, Crawley A P, Mikulis D J. NeuroReport. 1995;7:321–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiller C, May A, Limmroth V, Juptner M, Kaube H, Schayck R v, Coenen H H, Diener H C. Nat Med. 1995;1:658–660. doi: 10.1038/nm0795-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howland E W, Wakai R T, Mjaanes B A, Balog J P, Cleeland C S. Cognit Brain Res. 1995;2:165–172. doi: 10.1016/0926-6410(95)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitamura Y, Kakigi R, Hoshiyama M, Koyama S, Shimojo M, Watanabe S. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1995;95:463–474. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(95)00139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Craig A D, Reiman E M, Evans A C, Bushnell M C. Nature (London) 1996;384:258–260. doi: 10.1038/384258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Casey K L, Minoshima S, Morrow T J, Koeppe R A. Neurophysiology. 1996;76:571–581. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.1.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hsieh J C, Hannerz J, Ingvar M. Pain. 1996;67:59–68. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)03066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Antognini J F, Buonocore M H, Disbrow E A, Carstens E. Life Sci. 1997;61:349–354. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00960-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aziz Q, Andersson J L R, Valind S, Sundin A, Hamdy S, Jones A K P, Foster E R, Langstrom B, Thompson D G. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:50–59. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Di Piero V, Fiacco F, Tombari D, Pantano P. Pain. 1997;70:185–191. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03318-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silverman D H S, Munakata J A, Ennes H, Mandelkern M A, Hoh C K, Mayer E A. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:64–72. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Svensson P, Rosenberg B, Beydoun A, Morrow T J, Casey K L. Somatosens Mot Res. 1997;14:113–118. doi: 10.1080/08990229771114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Svensson P, Beydoun A, Morrow T J, Casey K L. Exp Brain Res. 1997;114:390–392. doi: 10.1007/pl00005648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu X P, Fukuyama H, Yazawa S, Mima T, Hanakawa T, Magata Y, Kanda M, Fujiwara N, Shindo K, Nagamine T, Shibasaki H. NeuroReport. 1997;8:555–559. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199701200-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Binkofski F, Schnitzler A, Enck P, Frieling T, Posse S, Seitz R J, Freund H-J. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:811–815. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Derbyshire S W G, Vogt B A, Jones A K P. Exp Brain Res. 1998;118:52–60. doi: 10.1007/s002210050254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iadarola M J, Berman K F, Zeffiro T A, Byas-Smith M G, Gracely R H, Max M B, Bennett G J. Brain. 1998;121:931–947. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.5.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.May A, Kaube H, Büchel C, Eichten C, Rijntjes M, Jüptner M, Weiller C, Diener H C. Pain. 1998;74:61–66. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oshiro Y, Fuijita N, Tanaka H, Hirabuki N, Nakamura H, Yoshiya I. NeuroReport. 1998;9:2285–2289. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199807130-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paulson P E, Monoshima S, Morrow T J, Casey K L. Pain. 1998;76:223–229. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00048-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hsieh J-C. Ph.D. thesis. Stockholm: Karolinska Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]