Abstract

Background

We investigated the role of different voltage sensitive calcium channels expressed at presynaptic afferent terminals in substance P release and on nociceptive behavior evoked by intraplantar formalin by examining the effects of intrathecally delivered N- (ziconotide), T- (mibefradil) and L-type voltage sensitive calcium channels blockers (diltiazem and verapamil).

Methods

Rats received intrathecal pretreatment with saline or doses of morphine, ziconotide, mibefradil, diltiazem or verapamil. The effect of these injections upon flinching evoked by intraplantar formalin (5%, 50μl) was quantified. To assess substance P release, the incidence of neurokinin 1 receptor internalization in the ipsilateral and contralateral lamina I was determined in immunofluorescent stained tissues.

Results

Intrathecal morphine (20μg), ziconotide (0.3, 0.6 and 1μg), mibefradil (100μg, but not 50μg), diltiazem (500μg, but not 300μg) and verapamil (200μg, but not 50 and 100μg) reduced paw flinching in phase 2 as compared to vehicle control (P < 0.05), with no effect upon phase 1. Ziconotide (0.3, 0.6 and 1μg) and morphine (20μg) significantly inhibited neurokinin 1 receptor internalization (P < 0.05), but mibefradil, diltiazem and verapamil at the highest doses had no effect.

Conclusion

These results emphasize the role in vivo of N-, but not T- and L-type voltage sensitive calcium channels in mediating the stimulus evoked substance P release from small primary afferents and suggest that T- and L-type voltage sensitive calcium channels blockers exert antihyperalgesic effects by an action on other populations of afferents or mechanisms involving post synaptic excitability.

Introduction

Small primary afferents are activated by a variety of high intensity thermal, mechanical and chemical stimuli. A subpopulation of these high threshold afferents contain and release excitatory amino acids and a variety of peptides. One population of such high threshold afferents, notably those that contain and release the peptide transmitter substance P1, project largely into the superficial dorsal horn, where they make synaptic contact with projection neurons that densely express Neurokinin 1 receptors (NK1r).2 Importantly, specific destruction of these NK1r (+) cells with substance P-Saporin, attenuated hyperpathic states initiated with tissue and nerve injury, emphasizing the functional relevance of these NK1r (+) cells to nociceptive processing.3,4,5

The release of substance P from these spinal terminals onto the NK1r (+) neurons is initiated by an increase in intracellular calcium secondary to the opening of voltage sensitive calcium channels (VSCCs) located on the central terminals from which this substance P release originates. VSCCs are classified into high-voltage-activated and low-voltage-activated channels. High-voltage-activated channels are further classified into L- (Cav1.1-1.4), P/Q- (Cav2.1), N- (Cav2.2) and R- (Cav2.3) types based on their activation kinetics, pharmacological sensitivities and α1-subunit sequences. Low-voltage-activated channel includes T-type VSCCs Cav (Ca3.1-3.3), which are activated in response to a small membrane depolarization.6-10

An important question relates to which one, if not all, of these channels play roles in mediating the release of transmitters from the small peptidergic afferents. With regard to their locations on primary afferents, L-type channels have been reported in myelinated and unmyelinated sensory axons.11,12 In the dorsal horn, L-type channel protein predominantly locates with neuronal soma and dendrites.13 N-type VSCCs predominate in lamina I largely located presynaptically on terminals and dendrites.13 Many substance P (+) nerve terminals also show colocalization with N-type VSCCs.13 Binding studies with omega-conotoxins indicate that the associated N-type channel is concentrated in laminae I and II on the superficial dorsal horn where small high threshold afferents terminate.14,15 T-type channel (Cav3.2 and Cav3.3) messenger RNA is present in dorsal root ganglion neurons. While some report transcripts to be only in small- and medium-sized neurons,16 others find Cav3.3 to be equally present in large dorsal root ganglion neurons.17 All members of the T-type VSCCs family are prominently expressed in lamina I.18,19 The role of the respective channels in afferent transmitter release may be assessed by the use of calcium channel antagonists. N-type channels are blocked by agents such as ω-conotoxin GVIA and their homologues, notably the commercially available ziconotide.20 L-type VSCCs are selectively blocked by 1, 4-dihydropyridines (such as nimodipine and nifedipine), phenyalkylamines (such as verapamil) and benzothiazepines (such as diltiazem).21 T-type channels are blocked by mibefradil.22

In spite of the apparent presence of many of the VSCCs species in afferents, electrophysiological studies in spinal slice preparations find that the monosynaptic postsynaptic depolarization of the superficial dorsal horn neurons in slices after root activation is diminished by N-type channel block and minimally by T- and L-type channel blocks.19,23 These observations on localization and electrophysiology raise the possibility that the N-, T- and L-type channels may contribute to varying degrees to release from peptidergic sensory neurons. Direct studies on peptide release (as a marker of small afferent terminal activity) have reported that N-type VSCCs blocker will prevent substance P release from primary afferents in ex vivo models.24-26 In contrast, L-type VSCCs blockers were reported to be without effect.25

In the present work, we examined the effects of intrathecally delivered N-, T- and L-type channel blockers to determine the effects on dorsal horn substance P release evoked by intraplantar formalin. To determine changes in extracellular substance P, we examined the internalization of the NK1 receptor. Previous work has shown that NK1r internalization is a robust index of extracellular substance P released from primary afferents.27-29 This methodology, in contrast to other in vivo (superfusion, dialysis) or in vitro (slice, culture) release approaches allows us to directly assess the effects of treatment on the release of substance P onto neurons known to be important in the spinal nociceptive pathway. As it is carried out in vivo, we can assess the relationship between drug effects upon release and the corresponding changes in behavior. Thus, the present studies will define the effects of the respective antagonists for N-, T- and L-type VSCCs given intrathecally on substance P release from small peptidergic primary afferents and the effects of these drugs on pain behavior at corresponding doses.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Holtzman Sprague-Dawley rats (250-300g; Harlan Indianapolis, IN) were individually housed in standard cages and maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 07h). Testing occurred during the light cycle. Food and water were available ad libitum. Animal care was in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health publication 85-23, Bethesda, MD) and as approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, San Diego, CA.

Intrathecal catheter implantation

Rats were implanted with a single intrathecal catheter for drug delivery, as described previously.30,31 In brief, rats were anaesthetized by induction with 4% isoflurane in a room air/oxygen mixture (1:1), and the anesthesia was maintained with 2% isoflurane delivery by mask. The animal was placed in a stereotaxic headholder and a midline incision was made on the back of the occipital bone to expose the cisternal membrane. The membrane was incised with a stab blade, and a single lumen polyethylene (outer diameter 0.36mm) catheter was inserted and passed into the intrathecal space to the level of the L2-L3 spinal segments (8.5cm). The other end of the catheter was joined to a polyethylene-10 catheter, which was tunneled subcutaneously to exit through the top of the head. The catheters were flushed with 10μl of saline and plugged. Rats were given 5ml of lactated Ringer's solution subcutaneously and allowed to recover under a heat lamp. If any showed motor weakness or signs of paresis on recovery from anesthesia, they were euthanized immediately. Animals were allowed to recover for 5-7 days before the experiment.

VSCCs blockade on formalin-induced paw-flinching

To assess formalin-induced flinching, a soft metal band (10mm wide) weighing ∼ 0.5g was placed around the left hindpaw of the animal being tested. Animals were allowed to acclimate in individual Plexiglas chambers for 30 min before experimental manipulation. For the VSCCs blockade studies, rats were administered saline, ziconotide (0.3, 0.6 or 1μg), mibefradil (50 or 100μg), diltiazem (300 or 500μg) or verapamil (50, 100 or 200μg) 10 min before a subcutaneous injection of formalin (5%, 50μl) into the dorsal side of the banded paw. Intrathecal morphine (20μg) was used as an active control. All drugs were injected intrathecally in a volume of 10μl followed by a 10μl saline flush. Immediately after the formalin injection, rats were placed individually into separate test chambers and nociceptive behavior (flinching and shaking of the injected paw) was quantified by an automatic flinch counting device (UARDG, Department of Anesthesiology, University of California, San Diego, CA).32 Flinches were counted in 1-min intervals for 60 min. The data were expressed as total number of flinches observed during phase 1 (0-10 min) and phase 2 (11-60 min). Animals were then euthanized.

VSCCs blockade on formalin-induced NK1r internalization

After recovery from intrathecal catheter implantation, rats received intrathecally saline, ziconotide (0.3, 0.6 or 1μg), mibefradil (50, 100 or 300μg), diltiazem (300 or 500μg) or verapamil (300μg). Intrathecal morphine (20μg) was used as an active control. Ten min after intrathecal drug administration, rats were anaesthetized with 4% isoflurane in a room air/oxygen mixture (1:1) and injected with formalin (5%, 50μl) to the left hindpaw. Rats were then transcardially perfused with fixative 10 min after the formalin injection.

Tissue preparation and immunocytochemistry

Anesthetized rats were transcardially perfused with 0.9% NaCl followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M sodium phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.4. The lumbar spinal cord was removed and postfixed overnight. After cryoprotection in 30% sucrose, coronal sections were made using a sliding microtome (30μm). Immunofluorescent staining was performed to examine NK1r expression in the spinal cord dorsal horn. In brief, sections were incubated in a rabbit anti-NK1r polyclonal antibody overnight at room temperature. The antibody was diluted to a concentration of 1:3000 in 0.01M phosphate buffered saline containing 10% normal goat serum and 10% Triton X-100. After rinsing in phosphate buffered saline, sections were then incubated for 120 min at room temperature in a goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa 488 to identify NK1 receptors and a goat anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa 594 to identify NeuN diluted at 1:1000 in 0.01M phosphate buffered saline containing 10% goat serum and 10% Triton X-100. All sections were finally rinsed and mounted on glass slides and coverslipped with ProLong mounting medium.

Quantification of NK1r internalization

Neurokinin 1 receptor internalization was counted using an Olympus BX-51 fluorescence microscope (Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan) at ×60 magnification and followed the standards outlined in previous reports.33,34 The total number of NK1r immunoreactive neurons an lamina I, with or without NK1r internalization, was counted and taken as a ratio of cells showing NK1r internalization versus all NK1r-positive cells and then converted into a percentage of NK1r-immunoreactive cells. Neuronal profiles that had 10 or more endosomes in their soma and the contiguous proximal dendrites were considered to have internalized NK1rs. NK1r-positive neurons in both sides of the dorsal horn were counted. The person counting the neurons was blinded to the experimental treatments. Mean counts from two to five sections per segment of the lumbar spinal cord were used as representative counts for a given animal. Three to five animals per drug treatment group were used for statistical analysis (n=3-5). Light microscopic images were taken using Magna FIRE SP (OPTRONICS, Goleta, CA) and processed by Photoshop CS4 (Adobe, San Jose, CA).

Effects of intrathecal ziconotide on NK1r internalization induced by exogenous substance P

To rule out the possibility that ziconotide directly blocks the NK1r internalization mechanism, the effect of ziconotide on internalization induced by exogenous substance P (intrathecal injection) was examined. Rats were administered intrathecal saline or ziconotide (0.6μg) 10min before intrathecal substance P (30 nmol). Thirty min after intrathecal substance P, rats were euthanized and fixed. The total number of NK1r immunoreactive neurons in lamina I, with or without NK1r internalization, was counted.

Behavioral and motor effects of intrathecal VSCCs blockade

Behavioral and motor effects of intrathecal VSCCs blockade were examined after the pretreatment according to methods described previously.21 Behavioral effects were assessed in a quiet environment and after stimuli, such as handling, a hand clap from 25cm (startle response), and toe pinching (withdrawal response). Motor function was examined by assessing the placing/stepping reflex, where normal behavior is a stepping reflex when the hindpaws are drawn across the edge of a table. Righting reflex was assessed by placing the rat horizontally with its back on the table, which normally gives rise to an immediate coordinated twisting of the body to an upright position. Before the examinations, behavioral and motor effects were assessed again. Rats with behavioral and motor dysfunction were removed.

Drug, antibody and materials

Ziconotide, mibefradil, diltiazem and verapamil were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St Louis, MO). Morphine sulfate was provided by Merck Pharmaceuticals (Rahway, NJ). Substance P was obtained from Peninsula Laboratory (Belmont, CA). All drugs were dissolved in saline and administered in a volume of 10μl followed by a 10μl saline flush. The rabbit anti-NK1r polyclonal antibody was purchased from the Advanced Targeting Systems (San Diego, CA). Secondary Alexa 488-conjugated antibody and Alexa 594-conjugated antibody were purchased from Invitrogen (Eugene, OR). Prolong mounting medium was from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Nomenclature for drugs and receptors conforms with the guide to receptors and channels of the British Journal of pharmacology.35

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by Prism 4 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Changes in formalin-induced paw-flinching behavior were analysed using t test or one-way analysis of variance for phases 1 and 2. Upon detection of a significant analysis of variance, Tukey's post hoc tests were performed for pair-wise comparisons of drug-treated groups with their phase 1 or 2. The analysis for NK1r internalization data consisted of t test or one-way analysis of variances. To detect the differences in the presence of a significant one-way analysis of variance, Tukey's post hoc analysis was conducted. In t test, P-value was expressed using two-tailed test. In all analyses, probability to detect the difference was set at the 5% level (P < 0.05).

Results

Intraplantar formalin injection evoked dorsal horn NK1r internalization

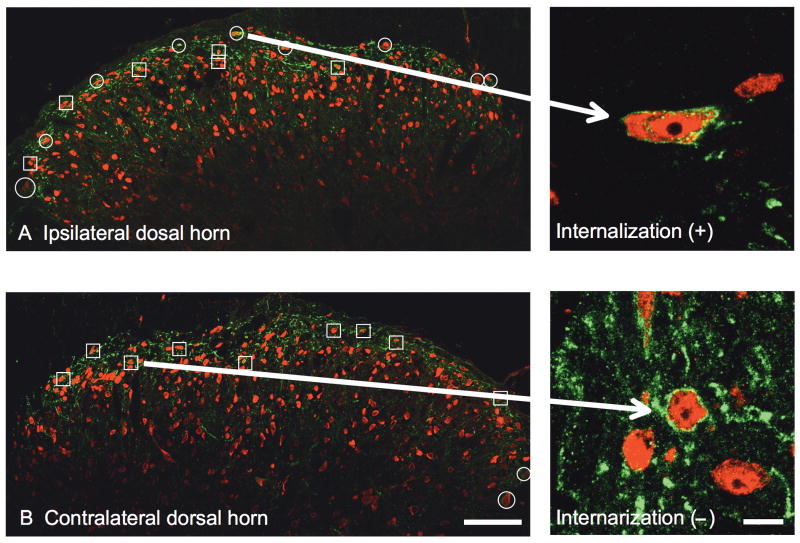

NK1-immunoreactivity was constitutively expressed in superficial dorsal horn neurons (Figure 1 A and 1B, Left). Examination of these sections at 63× revealed that in the absence of stimulation, a majority of these NK1(+) cells showed immunoreactivity distributed on the membrane surface (Figure 1B). Unilateral intraplantar injection of formalin (5%, 50μL) produced robust ipsilateral NK1r internalization, as evidenced by the appearance of NK1 (+) endosomes (Figure 1A, right). This internalization was typically most evident in lamina I at the L4-L6 levels of the lumbar spinal cord (Figure 1A). NK1r internalization was not observed on the contralateral side to the formalin-injected paw (Figure 1B, right).

Fig.1.

Representative confocal images of immune stained (red: NeuN; green: neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1r)) L6 dorsal horns ipsilateral (A) and contralateral (B) to the paw receiving intraplantar formalin in a rat administered intrathecal saline. Squares indicate the NK1r immunoreactive neurons without NK1r internalization. Circles indicate neurons showing NK1r internalization. In the ipsilateral dorsal horn, there are 15 NK1 (+) neurons with 9 showing NK1r internalizations. In the contralateral dorsal horn, there are 11 NK1r (+) neurons with 2 showing NK1r internalizations. Confocal images are taken at × 20. Scale bar is 100μm. The right pictures are conforcal images of NK1r immunoreactive neurons with (A) or without (B) NK1r internalization taken at × 63. Scale bar is 10μm.

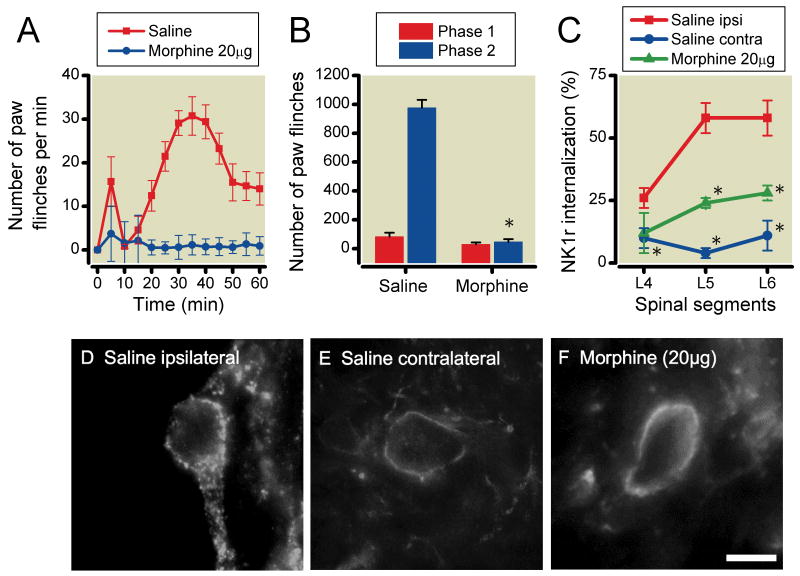

Effects of intrathecal morphine on formalin-induced paw-flinching behavior and NK1r internalization

The effects of intrathecal morphine on formalin-induced paw-flinching behavior and NK1r internalization in spinal lamina I are shown in Figure 2A-2F. Intrathecal 20μg morphine significantly reduced the formalin-induced paw-flinching behavior in phase 2 (saline: 976 ± 56, morphine 20μg: 47 ± 19, P<0.0001), but not phase 1 (saline: 83±27, morphine 20μg: 29±13, P=0.13) (Figure 2A and 2B). Intraplantar formalin (5%, 50μl) injection produced robust ipsilateral NK1r internalization in L5 and 6 compared to contralateral side (L4: ipsilateral 26±4% contralateral 10±4%, P=0.026, L5: ipsilateral 58±6% contralateral 4±2%, P<0.0001, L6: ipsilateral 58±7% contralateral 11±6%, P=0.0011) (Figure 2C-2E). 20μg morphine also significantly reduced the formalin-induced NK1r internalization at L5-L6 levels of ipsilateral spinal cord dorsal horn, as compared to vehicle control (L4: saline 26±4%, morphine 12±8%, P=0.14, L5: saline 58±6%, morphine 24±2%, P=0.0035, L6: saline 58±7%, morphine 28±3%, P=0.025) (Figure 2C and 2F).

Fig. 2.

Effects of intrathecal 20μg morphine on formalin-induced paw-flinching behavior and neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1r) internalization. (A) Time-effect curves of intrathecal morphine and saline on the formalin-induced paw-flinching. (B) Histogram showing cumulative flinching during phase 1 and phase 2. Intrathecal morphine significantly reduced phase 2 of formalin-induced paw-flinching. (C) Figure presents the percent of NK1r (+) neurons showing internalization versus spinal segment as a function of intrathecal treatment (saline vehicle ipsilateral, saline vehicle contralateral and morphine treatment ipsilateral). Unilateral intraplantar injection of formalin (5%) produced a robust ipsilateral NK1r internalization at L4-6 levels of lumbar lamina I compared with the contralateral side. Intrathecal morphine significantly reduced the formalin-induced NK1r internalization in the spinal segments L5-6 compared with saline. (D-F) Representative light microscopic images of NK1r internalization induced by unilateral injection of formalin (5%) into the hindpaw. (D) Image of formalin-induced NK1r internalization in the ipsilateral spinal lamina I from a rat administered intrathecal saline. Note the lack of a homogeneous cell membrane and the presence of NK1-containing endosomes internalizing into the cytoplasm. (E) Image of formalin-induced NK1r internalization in the contralateral spinal lamina I. Note the presence of a homogeneous cell membrane and the lack of NK1-containing endosomes internalizing into the cytoplasm. (F) Intrathecal morphine (20μg) blocked formalin-induced NK1r internalization. Data are presented as mean number of paw flinching and percentage of NK1r internalization with vertical bars showing S.E.M. *Represents a significant difference between saline-treated and drug-treated animal, P < 0.05. Images are taken at × 60. Scale bar is 10μm. In panel A and B, saline; n=6, morphine; n=5, in panel C, saline ipsilateral; n=5, contralateral; n=5, morphine; n=3.

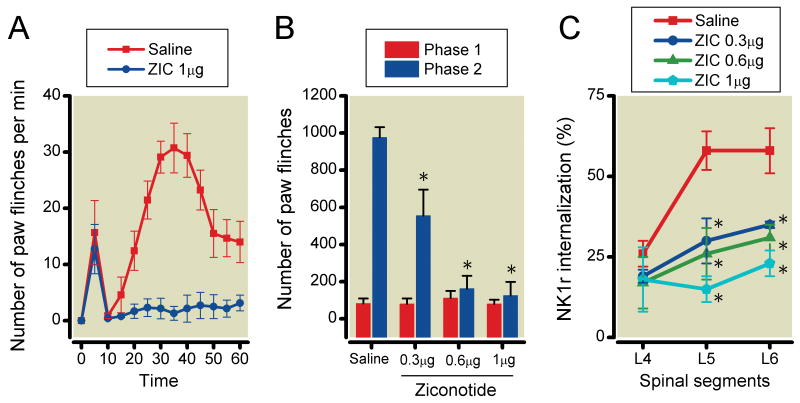

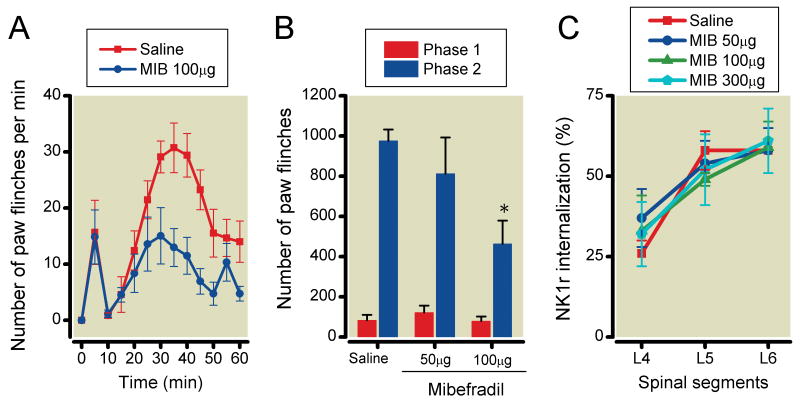

Effects of VSCCs blockade on formalin-induced paw-flinching behavior and NK1r internalization

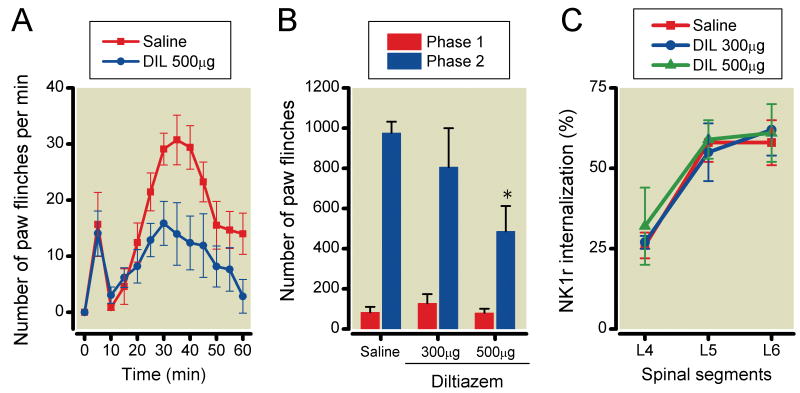

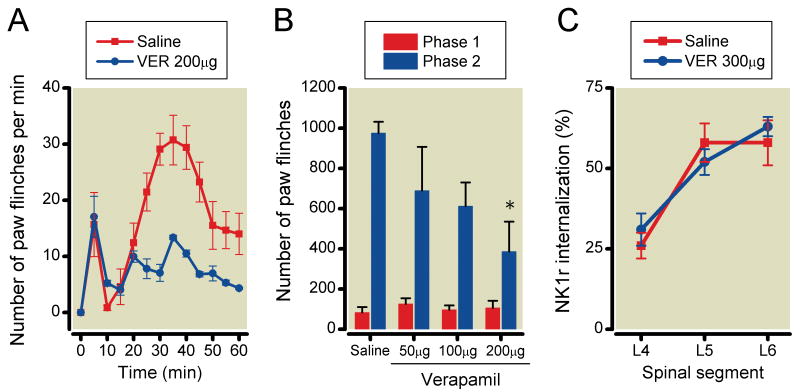

The effects of intrathecal ziconotide, mibefradil, diltiazem and verapamil on formalin-induced paw-flinching and NK1r internalization are shown in Figures 3-6, respectively. Ziconotide (0.3, 0.6 and 1μg) did not reduce the number of formalin-induced paw-flinching in phase 1 (0.3μg: 80±30, P>0.05, 0.6μg: 112±39, P>0.05, 1μg: 81±22, P>0.05), but reduced the phase 2 formalin-induced paw-flinching in a dose-dependent fashion as compared to vehicle control (0.3μg: 556±140, P<0.05, 0.6μg: 163±69, P<0.0001, 1μg: 126±73, P<0.0001) (Figure 3A and 3B). Ziconotide reduced formalin-induced NK1r internalization in L5 and L6 levels of spinal lamina I as compared with vehicle control (L4: 0.3μg 19±2%, P>0.05, 0.6μg 17±8%, P>0.05, 1μg 18±10%, P>0.05, L5: 0.3μg 30±7%, P<0.05, 0.6μg 26±8%, P<0.05, 1μg 15±4%, P<0.01, L6: 0.3μg 35±1%, P<0.05, 0.6μg 31±4%, P<0.05, 1μg 23±4%, P<0.01) (Figure 3C). Mibefradil (100μg but not 50) reduced formalin-induced paw-flinching in phase 2 (50μg: 813±180, P>0.05, 100μg: 464±115, P<0.05) but not phase 1 (50μg: 122±34, P>0.05, 100μg: 79±23, P>0.05) (Figure 4A and 4B). Mibefradil at the highest dose did not reduce formalin-induced NK1r internalization (L4: 50μg 37±9%, P>0.05, 100μg 33±11%, P>0.05, 300μg 32±10%, P>0.05, L5: 50μg 54±7%, P>0.05 100μg 49±2%, P>0.05, 300μg 52±11%, P>0.05, L6: 50μg 58±7%, P>0.05, 100μg 59±8%, P>0.05, 300μg 61±10%, P>0.05) (Figure 4C). Diltiazem (500μg but not 300μg) significantly reduced formalin-induced paw-flinching in phase 2 (300μg: 806±194, P>0.05, 500μg: 486±126, P<0.05) but not phase 1 (300μg: 128±46, P>0.05, 500μg: 80±21, P>0.05). Diltiazem at the highest dose had no effect on formalin-induced paw-flinching in phases 1 and 2 (Figure 5A and 5B) or upon formalin-induced NK1r internalization (L4: 300μg 27±2%, P>0.05, 500μg 32±12%, P>0.05, L5: 300μg 55±9%, P>0.05, 500μg 59±6%, P>0.05, L6: 300μg 62±8%, P>0.05, 500μg 61±9%, P>0.05) (Figure 5C). Verapamil (200μg but not 50 and 100μg) reduced formalin-induced paw-flinching in phase 2 (50μg: 690±217, P>0.05, 100μg: 612±118, P>0.05, 200μg: 386±149, P<0.05) but not phase 1 (50μg: 126±28, P>0.05, 100μg: 97±22, P>0.05, 200μg: 106±36, P>0.05) (Figure 6A and 6B). Verapamil, even at 300μg, did not reduce formalin-induced NK1r internalization (L4: 31±5%, P=0.41, L5: 52±4%, P=0.43, L6: 63±3%, P=0.65) (Figure 6C).

Fig. 3.

Effects of intrathecal ziconotide on formalin-induced paw-flinching behavior and neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1r) internalization. (A) Time-effect curves of intrathecal 1μg ziconotide and saline on the formalin-induced paw-flinching. (B) Intrathecal 0.3, 0.6 and 1μg ziconotide reduced phase 2 of formalin-induced paw-flinching. (C) Intrathecal 0.3, 0.6 and 1μg ziconotide reduced the formalin-induced NK1r internalization in the spinal segments L5-6 compared with saline. Data are presented as mean number of paw flinching and percentage of NK1r internalization with vertical bars showing S.E.M. *Represents a significant difference between saline-treated and drug-treated animal, P < 0.05. In panel A and B, saline; n=6, 0.3μg; n=5, 0.6μg; n=4, 1μg; n=4, in panel C, saline; n=5, 0.3μg; n=3, 0.6μg; n=3, 1μg; n=3.

Fig. 6.

Effects of intrathecal verapamil on formalin-induced paw-flinching behavior and neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1r) internalization. (A) Time-effect curves of intrathecal 200μg verapamil and saline on the formalin-induced paw-flinching. (B) Intrathecal 200, but not 50 and 100μg verapamil significantly reduced phase 2 of formalin-induced paw-flinching. (C) Intrathecal 300μg verapamil did not reduce the formalin-induced NK1r internalization. Data are presented as mean number of paw flinching and percentage of NK1r internalization with vertical bars showing S.E.M. *Represents a significant difference between saline-treated and drug-treated animal, P < 0.05. In panel A and B, saline; n=6, 50μg; n=3, 100μg; n=4, 200μg; n=4, in panel C, saline; n=5, 300μg; n=3.

Fig. 4.

Effects of intrathecal mibefradil on formalin-induced paw-flinching behavior and neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1r) internalization. (A) Time-effect curves of intrathecal 100μg mibefradil and saline on the formalin-induced paw-flinching. (B) Intrathecal 100μg, but not 50μg mibefradil significantly reduced phase 1 of formalin-induced paw-flinching. (C) Intrathecal 50 and 100μg mibefradil did not reduce the formalin-induced NK1r internalization. Data are presented as mean number of paw flinching and percentage of NK1r internalization with vertical bars showing S.E.M. *Represents a significant difference between saline-treated and drug-treated animal, P < 0.05. In panel A and B, saline; n=6, 50μg; n=5, 100μg; n=5, in panel C, saline; n=5, 50μg; n=3, 100μg; n=3, 300μg; n=3.

Fig. 5.

Effects of intrathecal diltiazem on formalin-induced paw-flinching behavior and neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1r) internalization. (A) Time-effect curves of intrathecal 500μg diltiazem and saline on the formalin-induced paw-flinching. (B) Intrathecal 500, but not 300μg diltiazem significantly reduced phase 2 of formalin-induced paw-flinching. (C) Intrathecal 300 and 500μg diltiazem did not reduce the formalin-induced NK1r internalization. Data are presented as mean number of paw flinching and percentage of NK1r internalization with vertical bars showing S.E.M. *Represents a significant difference between saline-treated and drug-treated animal, P < 0.05. In panel A and B, saline; n=6, 300μg; n=5, 500μg; n=5, in panel C, saline; n=5, 300μg; n=3, 500μg; n=3.

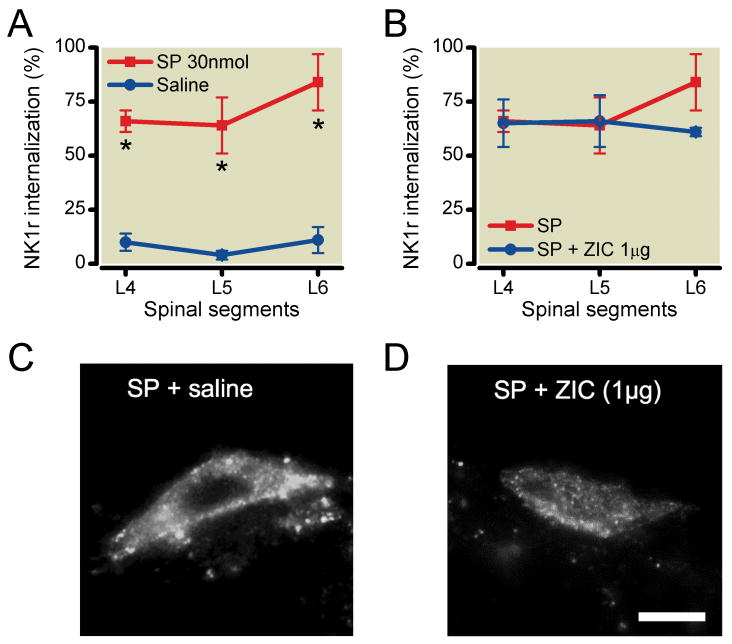

Effects of intrathecal ziconotide on NK1r internalization induced by exogenous substance P

To determine if agents preventing internalization were acting by a presynaptic action, we examined whether intrathecal ziconotide would alter NK1r internalization independent of a presynaptic mechanism. Accordingly, we showed that intrathecal substance P (30nmol) produced widespread formalin-induced NK1r internalization at L4-L6 levels of spinal cord lamina I compared with intrathecal saline (L4: saline 10±4%, substance P 66±5%, P<0.001, L5: saline 4±2%, substance P 64±13%, P<0.01, L6: saline 11±6%, substance P 84±13%, P<0.001) (Figure 7A). Intrathecal 0.6μg ziconotide, a dose that completely blocked formalin-induced NK1r internalization, did not, however, alter the exogenous substance P-induced NK1r internalization (L4: 65±11%, P>0.05, L5: 66±12%, P>0.05, L6: 61±2%, P>0.05) (Figure 7B-7D).

Fig. 7.

The effects of ziconotide on the neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1r) internalization induced by exogenous substance P. (A) Intrathecal substance P (30nmol) produced a robust bilateral NK1r internalization at L4-6 levels of lumbar lamina I compared with saline. (B) Pretreatment of intrathecal ziconotide (0.6μg) did not block NK1r internalization induced by intrathecal substance P. (C, D) Representative light microscopic images of NK1r internalization in lamina I after substance P alone (C), substance P after ziconotide (D). Data are presented as mean percentage of NK1r internalization with vertical bars showing S.E.M. *Represent a significant difference in NK1r internalization between saline-treated and drug-treated animal, P < 0.05. Images are taken at × 60. Scale bar is 10μm. Saline; n=5, substance P; n=3, substance P + ziconotide; n=3.

Behavioral and motor effects of intrathecal VSCCs blockade

During the experiment, ziconotide, mibefradil, diltiazem and verapamil caused dose dependent adverse effects on motor function (Table 1). In general, the adverse motor effects were dose dependent, showed an immediate onset and typically declined over the course of the experiment. As previously reported,36 ziconotide dose-dependently produced some adverse effects such as whole-body shaking, serpentine-like movement of the tail and ataxia. Mibefradil, diltiazem and verapamil typically produced a loss of hind paw function at the highest doses employed. It should be noted that while motor function was disturbed, this change in function did not impair the ability to flinch as evidenced by the lack of any effect upon phase 1 behavior. Moreover, flinching behavior was comparably observed in animals where there was little if any observable effect upon motor function. Morphine produced no adverse effects on behavior or motor function.

Table 1. Behavioral and motor effects of intrathecal voltage-sensitive calcium channels (VSCCs) blockers.

| Drug | Route | Dose (μg) |

n | % showing side effect | Side effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ziconotide | intrathecal | 0.3 | 8 | 38 | Body shaking, serpentine-like movement of the tail, ataxia |

| 0.6 | 7 | 43 | |||

| 1 | 9 | 56 | |||

| Mibefradil | intrathecal | 50 | 3 | 0 | Irreversible hindpaw paralysis ( > 2h ) |

| 100 | 3 | 0 | |||

| 300 | 4 | 75 | |||

| Diltiazem | intrathecal | 300 | 6 | 67 | Reversible hindpaw paralysis ( < 10 min ) |

| 500 | 5 | 80 | |||

| Verapamil | intrathecal | 50 | 3 | 0 | Reversible hindpaw paralysis ( < 10 min ) |

| 100 | 5 | 40 | |||

| 200 | 6 | 67 | |||

| Morphine | intrathecal | 20 | 5 | 0 |

Discussion

Tissue injury leads to the activation of small high threshold primary afferents which induces transmitter release from the dorsal horn terminals of those afferents. This terminal release is mediated by the opening of voltage sensitive calcium channels, which leads to increased intracellular calcium, and mobilization of transmitter vesicles, leading to exocytosis.37 An important component of this process is the identity of the VSCCs that must be involved in this process. As reviewed above, the three channel classes examined here are all present on small afferents. Electrophysiological studies in slices have, however, indicated that monosynaptic excitation evoked by root stimulation in slices is most strongly attenuated by N- and less so by L- and T-type channels.38 Such studies likely reflect upon the depolarization evoked by glutamate and not necessarily just by substance P. In the present studies, however, we found that release of substance P evoked by intraplantar formalin was blocked by doses of N-type channel blocker that blocked formain flinching, where L- and T-type channel blockades had significant effects upon flinching, but had no effect, even at higher doses, on substance P release. In the following sections we will consider several issues relevant to the interpretation of these studies.

Use of internalization to define substance P release

The NK1r is a G protein coupled receptor which internalizes when occupied by an agonist. The assertion that the degree of internalization reflects extracellular substance P derived from primary afferents is supported by several observations. i) Evoked internalization is lost in animals pretreated with doses of capsaicin which depletes the substance P in transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (+) afferent.29 ii) In spinal cord slices, there is a marked covariance between extracellular substance P and the fraction of cells showing internalization.27 and iii) Spinal opiates, which reduce extracellular substance P release through presynaptic action, reduces the fraction of spinal neurons that show NK1r internalization after stimulation with a noxious stimulus.29,39 iv) Conversely, intrathecal capsaicin which is known to evoke substance P release through activation of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 increases spinal NK1r internalization.40,41 v) We demonstrated that intrathecal ziconotide at a dose that blocked formalin evoked internalization had no effect upon the internalization evoked by direct NK1r activation using intrathecal substance P. Based on these several observations, we consider NK1r internalization to be a robust index of substance P release from spinal primary afferents and reduction of that internalization to be a marker for reduced release of substance P from those afferent terminals.

Role of N-, T- and L-type channels on formalin evoked pain behavior

In the present study, we characterized the effect of VSCCs blocker on formalin-induced paw-flinching behavior and in vivo substance P release from small primary afferents using NK1r internalization. In the present work, intrathecal ziconotide, mibefradil, diltiazem and verapamil reduced paw flinching behavior in phase 2. Previous work has shown that intrathecal N-type calcium channel blockers such as ziconotide are effective in a variety of models including those initiated by peripheral inflammation and by nerve injury.21,24,36,42,43 T-type VSCCs blockers such as mibefradil, have been reported to display analgesic effects in both phases of formalin-induced paw-flinching behavior.5,44 Previous work suggested that intrathecal L-type VSCC blockers, nimodipine and nifedipine had no effect on formalin-induced paw-flinching behavior, whereas verapamil and diltiazem produced modest, but significant inhibition.21 Importantly, these behavioral effects were observed at doses that did not produce motor dysfunction.

Effects on spinal substance P release

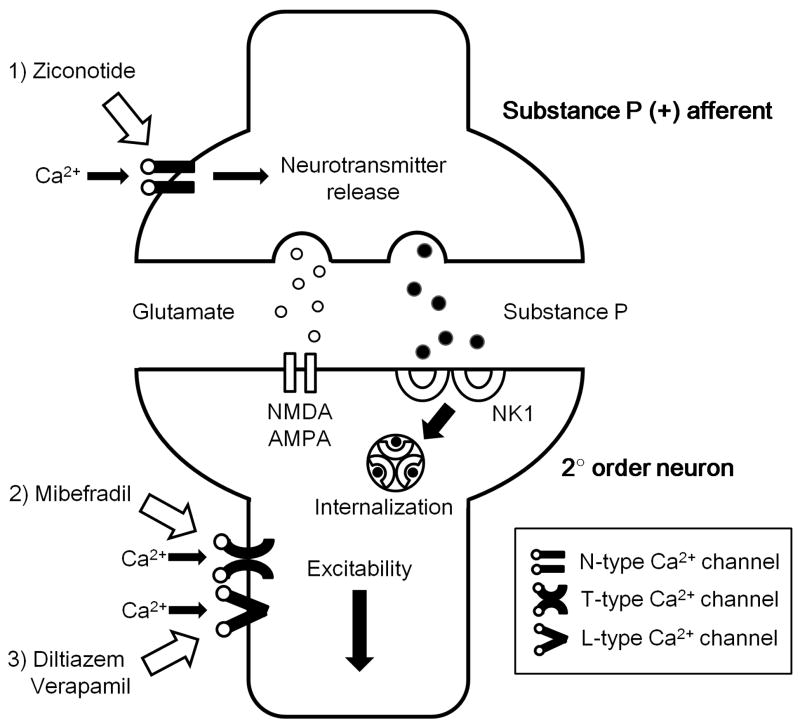

Previous studies have shown that inhibition of VSCCs via the activation of presynaptic μ opioid receptors serve to reduce the release from small primary afferents of nociceptive transmitters.29,39,45-47 In the present work, in spite of the reported presynaptic disposition of all three families of calcium channels, only the N-type channel blocker was found to be clearly effective in blocking release, suggesting its location on the terminals of small peptidergic primary afferents (Figure 8). These results are consistent with electrophysiological studies examining the effects of calcium channel blocker on monosynaptic evoked dorsal horn depolarization in spinal slices, where N-type channel blocker was highly effective as compared to T- and L-type channels.38

Fig. 8.

The role of voltage sensitive calcium channels (VSCCs) in nociceptive pathway in the spinal cord dorsal horn. 1) Ziconotide (N-type VSCCs blocker) inhibits Ca2+ influx then reduces releasing neurotransmitters such as substance P and glutamate at presynaptic terminals. 2) Mibefradil (T-type VSCCs blocker) inhibits Ca2+ influx at the dorsal root ganglion. Inhibition of Ca2+ influx inactivates a small depolarization and attenuates neuronal excitability and/or postsynaptic neurotransmitter release. 3) L-type VSCCs mainly locate on neuronal soma and dendrites. Diltiazem and verapamil (L-type VSCCs blocker) postsynaptically block Ca2+ influx and reduce excitability and/or postsynaptic neurotransmitter release. NMDA: N-methyl-D-aspartate, AMPA: α-amino-3-hydroxy- 5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid, NK1: neurokinin 1.

Previous studies have shown that intrathecal N-type VSCCs blocker reduced phase 2 of the formalin-induced paw-flinches and hyperalgesia initiated by knee joint inflammantion48 and intraplantar injection of capsaicin.49 Similarly, N-type VSCCs blocker suppressed the allodynia initiated by nerve ligation.6,36,42 Spinal N-type VSCCs are closely allied with processes that serve to augment the responses evoked by afferent input under the allodynic states.36 Results of the present study demonstrate that ziconitide dose dependently suppresses phase 2, not but phase 1 of formalin-induced paw flinching behavior. Within the same dose range, intrathecal ziconotide significantly reduced spinal substance P release.

The absence of effect of T- and L-type VSCCs blockers on release in the face of a significant effect on formalin flinching may reflect effects on non-substance P releasing afferents or a postsynaptic effect. As noted, the distribution of these calcium channels is not limited to the primary afferent but also noted on dorsal horn neuronal soma. Thus, T-type VSCCs exist in both presynaptic and postsynaptic sites of spinal sensory neurons and modulate synaptic transmission in the spinal cord dorsal horn.19,50,51 T-type VSCCs play an important role in the initiation of long-term potentiation at synapses between afferent C-fibers and lamina I projection neurons.37,50 Drdla and Sandkühler reported that spinal administration of mibefradil completely prevented long-term potentiation induction that was induced by low-frequency stimulation of C-fiber in the sciatic nerve.52 Todorovic and colleagues 53 reported work indicating that that T-type VSCCs facilitated pain signals in peripheral terminals of nociceptors. In the present work looking at the central terminals of substance P (+) afferents, mibefradil had no effect on release, suggesting a possible difference between the central and peripheral roles for this channel (Figure 8). With regard to L-type channels, previous work in slices reported that bradykinin-stimulated release of substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide were unaffected by the blockade of L-type VSCCs (nifedipine). In contrast, potassium-stimulated release of peptides was inhibited by nifedipine.54 The present work suggests that the postsynaptic effects of L-type VSCCs are important for the observed facilitatory actions (Figure 8).19,55,56

Important elements of these effects are that none of the agents, including ziconotide, had a measurable effect upon phase 1, even at the highest usable dose. This was unexpected and distinguished these effects from those agents that block substance P release, such as morphine, which dose dependently reduced phase 1 flinching. 32 This distinction for ziconotide suggests that the effect of this agent, in spite of the wide distribution of N-type channel, is surprisingly selective. Conversely, the effects on phase 1 may reflect upon the pre and postsynaptic actions of agents such as morphine. It is interesting to note that the predominate effects upon phase 1 versus phase 2 behavior reflect the profile of antihyperalgesic actions associated with the intrathecal effect of NK1 antagonists and the destruction of the superficial NK1 (+) lamina I neurons. 3,4,5,57

Motor effects

In the present study, at the highest doses, these agents produce reversible hindpaw paralysis that was observed immediately after injection. It has been reported that large doses of intrathecal diltiazem produced a reversible hindpaw paralysis that may be attributed to the local anesthesic action due to the blocking of Na+ channels.58 L-type VSCCs such as verapamil and diltiazem produce a local anesthetic effect as a result of inhibiting the fast Na+ inward current by Na+ channel blockade.59 Intrathecal ziconotide was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2004 for management of severe chronic pain. In cancer and Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome patients, following titrated intrathecal infusion, significant pain relief was observed with ziconotide.37 Because of the serious adverse effects, it has been recommended that ziconotide be used only for severe chronic pain refractory to other therapies.60,61 In humans, serious adverse effects such as nausea, dizziness, blurred vision, nystagmus, somnolence and asthenia, associated with the intrathecal ziconotide were reported.60-62 These adverse side effects vanished after ziconotide was discontinued.60 In animals, intrathecal administration of ziconotide produced dose-dependent reversible adverse effects21,63,64 In this study, intrathecal ziconotide produced adverse effects such as body shaking, serpentine-like movement of the tail, and ataxia (0.3μg: 38%, 0.6μg: 43%, 1μg: 56%). Consistent with these observations, the therapeutic index of intrathecal ziconotide is indeed narrow in the clinical setting.24

In conclusion, the present results show in vivo that the spinal delivery of N-type calcium channel blocker will reduce substance P release at doses that approximate those required to block the facilitated state in the formalin model. Blockers for the T- and L-type channels also had inhibitory effects upon the formalin-induced paw flinching; but at the highest doses examined, there were no effects upon substance P release. This suggests that T- and L-type channels may contribute to dorsal horn facilitated processing by mechanisms not involving the primary afferents.

MS #201009049 – Final Boxed Summary Statement.

What we already know about this topic

Ziconotide, an approved intrathecal drug for treating neuropathic pain, inhibits N-type voltage gated calcium channels as its presumed mechanism of action.

What this article tells us that is new

In rats, intrathecal ziconotide blocked neurokinin 1 receptor internalization, a measure of substance P release from small primary afferents.

Surprisingly, other spinal voltage gated calcium channel blockers produced antinociception, but did not reduce neurokinin 1 receptorinternalization.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Arbi Nazarian, Ph.D. (Assistant Professor, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Western University of Health Sciences, Pomona, California) for his assistance in setting up the internalization protocol.

Funding Support: This research was supported by funding from National Institutes of Health: NIH-DA02110, Bethesda, MD (TLY).

Footnotes

Preliminary data was presented as posters at the 13th World Congress on Pain, Montreal, Canada September 2nd, 2010.

Department and Institution to which work should be attributed: Department of Anesthesiology, University of California San Diego, California

References

- 1.Hökfelt T, Kellerth JO, Nilsson G, Pernow B. Substance p: Localization in the central nervous system and in some primary sensory neurons. Science. 1975;190:889–90. doi: 10.1126/science.242075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Littlewood NK, Todd AJ, Spike RC, Watt C, Shehab SA. The types of neuron in spinal dorsal horn which possess neurokinin-1 receptors. Neuroscience. 1995;66:597–608. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00039-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mantyh PW, Rogers SD, Honore P, Allen BJ, Ghilardi JR, Li J, Daughters RS, Lappi DA, Wiley RG, Simone DA. Inhibition of hyperalgesia by ablation of lamina I spinal neurons expressing the substance P receptor. Science. 1997;278:275–9. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5336.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nichols ML, Allen BJ, Rogers SD, Ghilardi JR, Honore P, Luger NM, Finke MP, Li J, Lappi DA, Simone DA, Mantyh PW. Transmission of chronic nociception by spinal neurons expressing the substance P receptor. Science. 1999;286:1558–61. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5444.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki R, Morcuende S, Webber M, Hunt SP, Dickenson AH. Superficial NK1-expressing neurons control spinal excitability through activation of descending pathways. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:1319–26. doi: 10.1038/nn966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cizkova D, Marsala J, Lukacova N, Marsala M, Jergova S, Orendacova J, Yaksh TL. Localization of N-type Ca2+ channels in the rat spinal cord following chronic constrictive nerve injury. Exp Brain Res. 2002;147:456–63. doi: 10.1007/s00221-002-1217-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao YQ. Voltage-gated calcium channels and pain. Pain. 2006;126:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng JK, Lin CS, Chen CC, Yang JR, Chiou LC. Effects of intrathecal injection of T-type calcium channel blockers in the rat formalin test. Behav Pharmacol. 2007;18:1–8. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3280141375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Catterall WA, Few AP. Calcium channel regulation and presynaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2008;59:882–901. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perez-Reyes E. Molecular physiology of low-voltage-activated t-type calcium channels. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:117–61. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlin KP, Jones KE, Jiang Z, Jordan LM, Brownstone RM. Dendritic L-type calcium currents in mouse spinal motoneurons: Implications for bistability. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:1635–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Westenbroek RE, Anderson NL, Byers MR. Altered localization of Cav1.2 (L-type) calcium channels in nerve fibers, Schwann cells, odontoblasts, and fibroblasts of tooth pulp after tooth injury. J Neurosci Res. 2004;75:371–83. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westenbroek RE, Hoskins L, Catterall WA. Localization of Ca2+ channel subtypes on rat spinal motor neurons, interneurons, and nerve terminals. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6319–30. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06319.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerr LM, Filloux F, Olivera BM, Jackson H, Wamsley JK. Autoradiographic localization of calcium channels with [125I] omega-conotoxin in rat brain. Eur J Pharmacol. 1988;146:181–3. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90501-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gohil K, Bell JR, Ramachandran J, Miljanich GP. Neuroanatomical distribution of receptors for a novel voltage-sensitive calcium-channel antagonist, SNX-230 (omega-conopeptide MVIIC) Brain Res. 1994;653:258–66. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90398-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Talley EM, Cribbs LL, Lee JH, Daud A, Perez-Reyes E, Bayliss DA. Differential distribution of three members of a gene family encoding low voltage-activated (T-type) calcium channels. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1895–911. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-01895.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yusaf SP, Goodman J, Pinnock RD, Dixon AK, Lee K. Expression of voltage-gated calcium channel subunits in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2001;311:137–41. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berridge MJ, Lipp P, Bootman MD. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:11–21. doi: 10.1038/35036035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinke B, Balzer E, Sandkühler J. Pre- and postsynaptic contributions of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels to nociceptive transmission in rat spinal lamina I neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:103–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.03083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malmberg AB, Yaksh TL. Effect of continuous intrathecal infusion of omega-conopeptides, N-type calcium-channel blockers, on behavior and antinociception in the formalin and hot-plate tests in rats. Pain. 1995;60:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00094-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malmberg AB, Yaksh TL. Voltage-sensitive calcium channels in spinal nociceptive processing: Blockade of N- and P-type channels inhibits formalin-induced nociception. J Neurosci. 1994;14:4882–90. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-08-04882.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dogrul A, Gardell LR, Ossipov MH, Tulunay FC, Lai J, Porreca F. Reversal of experimental neuropathic pain by T-type calcium channel blockers. Pain. 2003;105:159–68. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rycroft BK, Vikman KS, Christie MJ. Inflammation reduces the contribution of N-type calcium channels to primary afferent synaptic transmission onto NK1 receptor-positive lamina I neurons in the rat dorsal horn. J Physiol. 2007;580:883–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-02117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith MT, Cabot PJ, Ross FB, Robertson AD, Lewis RJ. The novel N-type calcium channel blocker, AM336, produces potent dose-dependent antinociception after intrathecal dosing in rats and inhibits substance P release in rat spinal cord slices. Pain. 2002;96:119–27. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00436-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holz GG, 4th, Dunlap K, Kream RM. Characterization of the electrically evoked release of substance P from dorsal root ganglion neurons: methods and dihydropyridine sensitivity. J Neurosci. 1988;8:463–71. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-02-00463.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maggi CA, Tramontana M, Cecconi R, Santicioli P. Neurochemical evidence for the involvement of N-type calcium channels in transmitter secretion from peripheral endings of sensory nerves in guinea pigs. Neurosci Lett. 1990;114:203–6. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90072-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marvizón JC, Wang X, Matsuka Y, Neubert JK, Spigelman I. Relationship between capsaicin-evoked substance P release and neurokinin 1 receptor internalization in the rat spinal cord. Neuroscience. 2003;118:535–45. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00977-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mantyh PW. Neurobiology of substance P and the NK1 receptor. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kondo I, Marvizon JC, Song B, Salgado F, Codeluppi S, Hua XY, Yaksh TL. Inhibition by spinal mu- and delta-opioid agonists of afferent-evoked substance P release. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3651–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0252-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yaksh TL, Rudy TA. Chronic catheterization of the spinal subarachnoid space. Physiol Behav. 1976;17:1031–6. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(76)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malkmus SA, Yaksh TL. Intrathecal catheterization and drug delivery in the rat. Methods Mol Med. 2004;99:109–21. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-770-X:011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yaksh TL, Ozaki G, McCumber D, Rathbun M, Svensson C, Malkmus S, Yaksh MC. An automated flinch detecting system for use in the formalin nociceptive bioassay. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:2386–402. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.6.2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mantyh PW, Allen CJ, Ghilardi JR, Rogers SD, Mantyh CR, Liu H, Basbaum AI, Vigna SR, Maggio JE. Rapid endocytosis of a G protein-coupled receptor: Substance P evoked internalization of its receptor in the rat striatum in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:2622–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abbadie C, Trafton J, Liu H, Mantyh PW, Basbaum AI. Inflammation increases the distribution of dorsal horn neurons that internalize the neurokinin-1 receptor in response to noxious and non-noxious stimulation. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8049–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-20-08049.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alexander SP, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC) Br J Pharmacol. (3rd) 2008;153:S1–209. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaplan SR, Pogrel JW, Yaksh TL. Role of voltage-dependent calcium channel subtypes in experimental tactile allodynia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;269:1117–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yaksh TL. Calcium channels as therapeutic targets in neuropathic pain. J Pain. 2006;7:S13–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Motin L, Adams DJ. omega-Conotoxin inhibition of excitatory synaptic transmission evoked by dorsal root stimulation in rat superficial dorsal horn. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:860–4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yaksh TL, Jessell TM, Gamse R, Mudge AW, Leeman SE. Intrathecal morphine inhibits substance P release from mammalian spinal cord in vivo. Nature. 1980;286:155–7. doi: 10.1038/286155a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jhamandas K, Yaksh TL, Harty G, Szolcsanyi J, Go VL. Action of intrathecal capsaicin and its structural analogues on the content and release of spinal substance P: Selectivity of action and relationship to analgesia. Brain Res. 1984;306:215–25. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90371-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nazarian A, Gu G, Gracias NG, Wilkinson K, Hua XY, Vasko MR, Yaksh TL. Spinal N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors and nociception-evoked release of primary afferent substance P. Neuroscience. 2008;152:119–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bowersox SS, Gadbois T, Singh T, Pettus M, Wang YX, Luther RR. Selective N-type neuronal voltage-sensitive calcium channel blocker, SNX-111, produces spinal antinociception in rat models of acute, persistent and neuropathic pain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;279:1243–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saegusa H, Matsuda Y, Tanabe T. Effects of ablation of N- and R-type Ca(2+) channels on pain transmission. Neurosci Res. 2002;43:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(02)00017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barton ME, Eberle EL, Shannon HE. The antihyperalgesic effects of the T-type calcium channel blockers ethosuximide, trimethadione, and mibefradil. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;521:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schroeder JE, Fischbach PS, Zheng D, McCleskey EW. Activation of mu opioid receptors inhibits transient high- and low-threshold Ca2+ currents, but spares a sustained current. Neuron. 1991;6:13–20. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90117-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang HM, Berde CB, Holz GG, 4th, Steward GF, Kream RM. Sufentanil, morphine, met-enkephalin, and kappa-agonist (U-50,488H) inhibit substance P release from primary sensory neurons: A model for presynaptic spinal opioid actions. Anesthesiology. 1989;70:672–7. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198904000-00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gu G, Kondo I, Hua XY, Yaksh TL. Resting and evoked spinal substance P release during chronic intrathecal morphine infusion: Parallels with tolerance and dependence. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:1362–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.087718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sluka KA. Blockade of N- and P/Q-type calcium channels reduces the secondary heat hyperalgesia induced by acute inflammation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;287:232–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sluka KA. Blockade of calcium channels can prevent the onset of secondary hyperalgesia and allodynia induced by intradermal injection of capsaicin in rats. Pain. 1997;71:157–64. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)03354-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ikeda H, Heinke B, Ruscheweyh R, Sandkühler J. Synaptic plasticity in spinal lamina I projection neurons that mediate hyperalgesia. Science. 2003;299:1237–40. doi: 10.1126/science.1080659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bao J, Li JJ, Perl ER. Differences in Ca2+ channels governing generation of miniature and evoked excitatory synaptic currents in spinal laminae I and II. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8740–50. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08740.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Drdla R, Sandkühler J. Long-term potentiation at C-fibre synapses by low-level presynaptic activity in vivo. Mol Pain. 2008;4:18. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Todorovic SM, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Meyenburg A, Mennerick S, Perez-Reyes E, Romano C, Olney JW, Zorumski CF. Redox modulation of T-type calcium channels in rat peripheral nociceptors. Neuron. 2001;31:75–85. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00338-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Evans AR, Nicol GD, Vasko MR. Differential regulation of evoked peptide release by voltage-sensitive calcium channels in rat sensory neurons. Brain Res. 1996;712:265–73. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01447-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perrier JF, Alaburda A, Hounsgaard J. Spinal plasticity mediated by postsynaptic L-type Ca2+ channels. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2002;40:223–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fossat P, Sibon I, Le Masson G, Landry M, Nagy F. L-type calcium channels and NMDA receptors: A determinant duo for short-term nociceptive plasticity. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:127–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamamoto T, Yaksh TL. Stereospecific effects of a nonpeptidic NK1 selective antagonist, CP-96,345: Antinociception in the absence of motor dysfunction. Life Sci. 1991;49:1955–63. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90637-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hara K, Saito Y, Kirihara Y, Sakura S, Kosaka Y. Antinociceptive effects of intrathecal L-type calcium channel blockers on visceral and somatic stimuli in the rat. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:382–7. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199808000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leszczynska K, Kau ST. A sciatic nerve blockade method to differentiate drug-induced local anesthesia from neuromuscular blockade in mice. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 1992;27:85–93. doi: 10.1016/1056-8719(92)90026-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Atanassoff PG, Hartmannsgruber MW, Thrasher J, Wermeling D, Longton W, Gaeta R, Singh T, Mayo M, McGuire D, Luther RR. Ziconotide, a new N-type calcium channel blocker, administered intrathecally for acute postoperative pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2000;25:274–8. doi: 10.1016/s1098-7339(00)90010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lynch SS, Cheng CM, Yee JL. Intrathecal ziconotide for refractory chronic pain. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1293–300. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Penn RD, Paice JA. Adverse effects associated with the intrathecal administration of ziconotide. Pain. 2000;85:291–6. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00254-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hama A, Sagen J. Antinociceptive effects of the marine snail peptides conantokin-G and conotoxin MVIIA alone and in combination in rat models of pain. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:556–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen JQ, Zhang YQ, Dai J, Luo ZM, Liang SP. Antinociceptive effects of intrathecally administered huwentoxin-I, a selective N-type calcium channel blocker, in the formalin test in conscious rats. Toxicon. 2005;45:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]