Abstract

In this paper, a detailed numerical and experimental investigation into the optimisation of hydrodynamic micro-trapping arrays for high-throughput capture of single polystyrene (PS) microparticles and three different types of live cells at trapping times of 30 min or less is described. Four different trap geometries (triangular, square, conical, and elliptical) were investigated within three different device generations, in which device architecture, channel geometry, inter-trap spacing, trap size, and trap density were varied. Numerical simulation confirmed that (1) the calculated device dimensions permitted partitioned flow between the main channel and the trap channel, and further, preferential flow through the trap channel in the absence of any obstruction; (2) different trap shapes, all having the same dimensional parameters in terms of depth, trapping channel lengths and widths, main channel lengths and widths, produce contrasting streamline plots and that the interaction of the fluid with the different geometries can produce areas of stagnated flow or distorted field lines; and (3) that once trapped, any motion of the trapped particle or cell or a shift in its configuration within the trap can result in significant increases in pressures on the cell surface and variations in the shear stress distribution across the cell’s surface. Numerical outcomes were then validated experimentally in terms of the impact of these variations in device design elements on the percent occupancy of the trapping array (with one or more particles or cells) within these targeted short timeframes. Limitations on obtaining high trap occupancies in the devices were shown to be primarily a result of particle aggregation, channel clogging and the trap aperture size. These limitations could be overcome somewhat by optimisation of these device design elements and other operational variables, such as the average carrier fluid velocity. For example, for the 20 μm polystyrene microparticles, the number of filled traps increased from 32% to 42% during 5–10 min experiments in devices with smaller apertures. Similarly, a 40%–60% reduction in trapping channel size resulted in an increase in the amount of filled traps, from 0% to almost 90% in 10 min, for the human bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells, and 15%–85% in 15 min for the human embryonic stem cells. Last, a reduction of the average carrier fluid velocity by 50% resulted in an increase from 80% to 92% occupancy of single algae cells in traps. Interestingly, changes in the physical properties of the species being trapped also had a substantial impact, as regardless of the trap shape, higher percent occupancies were observed with cells compared to single PS microparticles in the same device, even though they are of approximately the same size. This investigation showed that in microfluidic single cell capture arrays, the trap shape that maximizes cell viability is not necessarily the most efficient for high-speed single cell capture. However, high-speed trapping configurations for delicate mammalian cells are possible but must be optimised for each cell type and designed principally in accordance with the trap size to cell size ratio.

INTRODUCTION

Traditionally, investigations into the biology and physiology of cells invitro are conducted on large cell ensembles (103–107 cells/ml), and individual cellular properties and behaviours, as a result, are often averaged over the entire population.1, 2 Cell populations are rarely homogeneous in terms of phenotype, for example, their position in the cell cycle, their morphology and size, and gene expression. The lack of an intrinsic capability in traditional cell culture protocols for high throughput assessment of changes in the properties of individual cells within a population, in the absence of experimental robotic culture systems and integrated flow assisted cell sorting (FACS), represents a significant limitation in the field of stem cells, where researchers and industry require knowledge of the definitive status of cell phenotypes during each stage of expansion, maturation, or differentiation. To understand the impact of a stem cell’s initial phenotype (post isolation or extraction from their invivo niche) on subsequent fate decisions, including proliferation, self-renewal, differentiation, and apoptosis, and hence, potentially, their ultimate therapeutic potential, studies at the single cell level are necessary.3, 4, 5, 6, 7

Whilst FACS has in the past been the principal method by which biologists and bioengineering researchers have isolated and sorted single cells based on defined cell properties (such as size or surface-bound fluorophores ascribed to targeted surface markers), the extreme sensitivity of stem cells, and in fact many of other cell types, to the high shear stresses imposed on them during FACS-based processing can result in significant cell death and hence loss of representative sampling across the whole population.

Microfluidic devices, being relatively inexpensive and easy to fabricate, have proven to be useful analytical tools for a diverse range of biological experiments,8 especially due to them only requiring small cell numbers and media (and reagent) volumes for experiments. However, although microfluidic devices have substantive advantages to offer, and they are certainly becoming more widely used in bioengineering laboratory settings, they often require a significant investment in ancillary equipment (e.g., expensive syringe pumps) and have certain limitations that are imposed by the intrinsic small lengthscales within these devices (O ∼ 10 s–100 s of microns), resulting in, for example, long experimental times due to low volumetric flow rate limitations (depending somewhat on the material used in their fabrication). They are often not optimized or designed from the outset to be simple, everyday bench-top setups capable of being used by non-expert research or development laboratories, that is, by laboratories without significant expertise in operating cell-based microfluidic devices. This limits their translation to biologists and other researchers interested in exploiting their intrinsic ability to provide stable and reproducible results in a variety of laboratory settings.

As a case in point, recent investigations have proposed the use of microfabricated microfluidic devices to isolate or select (trap) single cells from high number density cell populations.4, 5 Whilst these elegant devices have proven utility in performing this function, they suffer from variable trapping efficiencies and, most importantly, low throughput. A fast microfluidic single cell trapping design must have high trapping efficiencies and be medium to high throughput. This will not only reduce the time required for arraying single cells, but it is a necessity to maximising the on-chip viability of cells being trapped or isolated, which represents a substantial advantage over present FACS-based protocols.

The hydrodynamic design concepts used in single cell trapping microfluidic devices to date has depended on the aim of the study and type of particles or cells. For example, many studies employ flow chambers, for use as a cytometer, with arrays of small, micropatterned wells to catch cells from a suspension flowing through them under positive pressure (i.e., using syringe pumps) or withdrawn via an applied suction pressure. The cells are trapped solely based on the collision of cells with traps and whilst achieving medium to high throughput processing of cells, they generally demonstrate low efficiencies of 10%–30%.4 Another device concept involves immobilizing or trapping a particle using hydrodynamic forces. These studies have used the forces generated by focused fluids in opposing flow paths to essentially “pin” a cell or cluster of cells in a microchannel junction.9, 10 These devices are useful for single cell genomics but not for high throughput screening and selection. Last, microfluidic-based single cell isolation arrays utilise the principal of “paths of least flow resistance” to initially direct a single cell into a trap, which results in this lead cell “blocking” the dominant flow path and thereafter redirecting subsequent cells through the next “path of least flow resistance” containing similar traps. This particular design concept, which is well established in the literature,11, 12, 13 can successfully fill 10%–80% of traps (representing percent occupancy) with up to 97% of them being filled with single particles or cells. Currently, the most efficient and fastest device filled 99% of traps with single human epithelial-like cells within 30 min.11 However, this study was done with only 200 traps per device, contrary to the more dense arrays used in previous, slower trapping experiments.12, 13 Scaling up to a higher density of traps is a significant challenge, as is adapting these devices to a wide variety of cell types. To incorporate more traps in a device, longer microchannels are needed, which significantly increases the total pressure drop across the device. This scheme requires a lower flow rate operation to counteract the increased pressure difference, which prolongs trapping experiments and diminishes the high throughput performance and ultimately the viability of cells within these devices.

Many mammalian stem, progenitor, and differentiated cells proposed as ideal cell sources for regenerative medicine applications are particularly delicate and sensitive to environmental conditions.14 Therefore, a major concern in cell assay applications is the mechanical forces exerted on cells by fluids, which can influence cell phenotype and fate decisions.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 For example, it has been established that shear stresses up to 4.5 Pa can actually help to inhibit apoptosis for human endothelial cells.20 Even in non-mammalian systems, external stresses can have detrimental implications on the cells. For example, algae cells have been shown to have compromised viability at stresses exceeding 1 Pa.21 Therefore, depending on the application of the trapping mechanism, any prolonged shearing of cells with fluid may or may not produce a desirable effect. This must be taken into consideration when optimizing lab-on-a-chip single cell isolation devices, as short trapping times will likely be accompanied by high velocities. On the contrary, inorganic microparticles, such as the polymeric-based materials used in controlled release drug delivery,22 can withstand shear stress regimes above that of biological matter, which whilst decreasing the number of design concerns in their use in high-speed microfluidic trapping arrays, do raise the concern of using them as a model system for devices aimed at cell-based applications.

In order to optimize high throughput screening and selection, it is necessary to correlate the kinematics of a trap and a trap’s physical geometry with the different types of cells being arrayed. Major factors impacted by the specific geometry of a trap include the trap’s ability to array large amounts of single cells or particles with high accuracy and the fluid shear forces generated during fast trapping. Other sensitivities affecting efficiency of fast trapping are any geometrical variability due to small-scale microfabrication, the microfluidic inlet and outlet channels, and the input concentration of the cell/particle suspension.

In this work, we aimed to develop optimisation protocols to improve the efficiency of a micro-trapping array based on previously proposed hydrodynamic design conditions.11, 12, 13 First, we present a numerical simulation of flow through the device to confirm the hydrodynamic conditions, determine the geometrical parameters that impact the flow, and pinpoint a velocity regime at which the design begins to fail. Second, we investigate the impact of different trap shapes on the efficiency of single cell or particle capture in a stable velocity regime confirmed by simulation. Finally, we apply our results to optimise the high-throughput performance for experimental trapping times on the order of minutes, not only for microparticles but also for human embryonic and mesenchymal stem cells and algae cells. The resultant microdevice can achieve very high capture efficiencies based on one particle or cell per trap, at velocities and in timeframes that permit optimal cell viability of trapped cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Device design

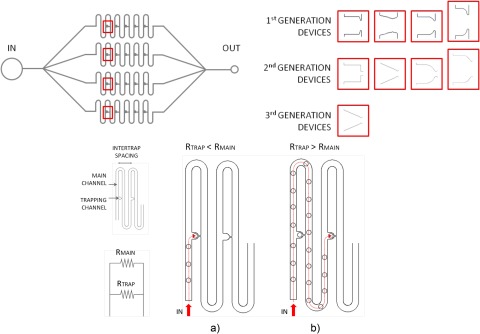

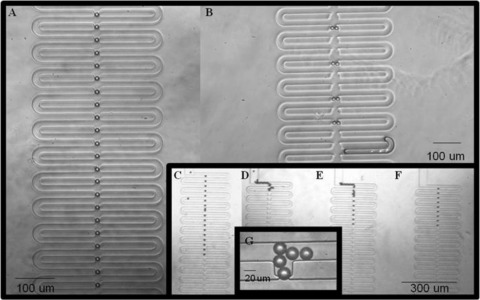

The microfluidic device architecture was designed with l-edit software (Tanner Research) and autocad 2009 (Autodesk, Inc.). The main design structure is based on the “Tan and Takeuchi” model.13 It consisted of parallel, serpentine microchannels connected to fluid inlet and outlet ports. These networks contained the hydrodynamic traps equally spaced along the channel. This elegant design concept requires the establishment of differential flow resistances along a section of the serpentine (main) channel that encourages fluid to preferentially flow through a connecting channel between two adjacent curved sections of the main channel, but only in the absence of a particle or cell being lodged (trapped) in this connecting channel (see Figure 1). A particle or cell being transported along the main channel is thus preferentially forced to enter the trap and thereafter the dominant flow path is that of the main channel, until the next open connecting channel is reached (see Fig. 1). Four different trap shapes were assessed: triangular, square, conical, and elliptical.

Figure 1.

(Top) Schematic of trapping arrays and the three device generations utilized for all experiments; (bottom) explanation of the mechanism behind hydrodynamic trapping of single cells: (a) trapping mode and (b) bypassing mode.

Microfabrication

The designs were printed on silicon wafers (4 in. diameter) through SU-8 (2025) negative UV lithography, using a glass mask patterned with a photoplotter (MIVA). The microfluidic chips were molded through Poly dimethyl siloxane (PDMS) soft lithography process using Sylgard 184 silicone elastomer and curing agent. The molds were degassed at room temperature for 45 min and cured at 65 °C for 2 h.

After curing and cutting out the individual devices from the mold, inlet and outlet ports were created in the PDMS using a 1 and 3.5 mm diameter hole punch, respectively. The molds were then irreversibly bonded to glass sides through a 20 s O2 plasma treatment at medium RF level. The resulting PDMS-glass devices were placed in a furnace for 1 h at 65 °C to allow for the inter-material bonds to strengthen.

Device evolution

Three generations of PDMS microfluidic devices were used over the course of all experiments, with modifications made to the channel geometries based on the experimental results of trapping. These are shown in Fig. 1. The first set of devices (generation 1) consisted of 4 branching main channels with 100 traps per shape, presenting a total of 400 traps per device. These channels were designed for trapping 20 μm particles or cells. The inlet and outlet channels to the arrays were 100 μm in width, while the main channels were 25 μm in width. Traps were designed to be 25 μm in depth, with the trapping channels 10–18 μm in width. Also, generation 1 devices had inter-trap spacings of 281 μm and 25 μm high channels.

A second set of devices (generation 2) consisted of larger inter-trap spacings, higher trap density, smaller trap channels, and tapering inlet and outlet channels. The trap arrays consisted of 1056 traps per device with 264 traps per shape. Inter-trap spacings were increased to around 1700 μm, the trap channels were decreased to 5–10 μm, and the inlet/outlet channels tapered from 100 μm to 50 μm, before reaching the 25 μm main trapping serpentine networks. Individual traps still remained at 25 μm in depth for targeting 20 μm particles or cells. The height of all channels was kept at 25 μm.

The results obtained for the generations 1 and 2 devices allowed for the optimization of geometrical features for generation 3 devices. In particular, the triangular trap geometry was utilized and scaled down in order to trap smaller cellular species on the order of 2–15 μm in diameter. Trapping channels were decreased to 1–5 μm, trap depths were 10 μm, and inter-trap spacings were 1000 μm. The inlet and outlet channels were 100 μm wide.

Optical profilometry

Non-contact white-light optical profilometry of all microfabricated SU-8 master structures was performed with a WYKO NT 1100 optical profilometer (Veeco, Plainview, NY). Samples were secured to the profiler stage via vacuum. Resulting microchannel heights and thicknesses were determined with a 20x objective operating in vertical scanning interferometry (VSI) mode with a field of vision (FOV) of 0.5, and a back scan of ±5 μm. The basic interferometric principle in VSI is that light reflected from a reference mirror combines with light reflected from a sample to produce interference fringes, where the best-contrast fringe occurs at best focus. In VSI mode, the white-light source is filtered with a neutral density filter, which preserves the short coherence length of the white light, and the system measures the degree of fringe modulation, or coherence, instead of the phase of the interference fringes. Both 2D analysis and 3D interactive plots of the SU-8 patterns were generated with wyko vision 31 analytical software (Veeco).

Microfluidic setup and operation

Microfluidic experiments were performed on a Nikon C1-T-SM confocal microscope connected to a high-speed camera (phantom v. 5.0) for image acquisition. PHD 2000 Infuse/Withdraw syringe pumps were operated in withdrawal mode for all experiments to achieve average (main channel) fluid velocities (based on flowrate-to-main channel area ratios) that ranged from 0.1 to 6 mm/s depending on the generation of device. This regime was chosen based on the results from preliminary numerical simulation (Sec. 2G), which demonstrated this would be a range with a stable flow profile. In general, the maximal achievable velocity with our pump setup was around 6 mm/s with these specific designs of devices. For the third generation devices, which were for the smallest cell species (∼10 μm or less), the maximal velocities used were 0.1 mm/s, mainly because this range was optimal after considering the physical properties of the specific cells tested in those devices. The cell or particulate suspension was placed at the 3.5 mm diameter inlet, and drawn through the device, exiting the 1 mm outlet through polyethylene tubing connected to the syringe.

Cell culture and suspensions preparation

Bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)

MSCs were isolated from the bone marrow of healthy 18–60 yr old volunteers after obtaining written informed consent (Mater Hospital Services (MHS) Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) number 740 A, MMRI ethics number 32). Briefly, 10 ml bone marrow aspirate taken from the iliac crest was resuspended in 20 ml phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and the mononuclear fraction separated by Percoll density gradient. The mononuclear cells were resuspended in low glucose Dulbecco's Modified Eagles Media (DMEM) supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin (10 000 units Gibco/Invitrogen Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and cultured in tissue culture flasks at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 in air environment. After 24 h non-adherent cells were removed by exchanging the medium and the remaining cells cultured with media changes every 3–4 days and passaging at 80% confluence. hMSCs at P4 were characterised by flow cytometry expressing surface markers CD29, CD44, CD49a, CD73, CD90, CD105, CD146, CD166, and negative for CD34 and CD45. The cells displayed tri-lineage differentiation potential along the osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic lineages. For the trapping experiments, adherent 80% confluent hMSCs were passaged and cell suspensions at desired number densities formulated. To do so, the media was removed, and then the attached cells were washed twice with sterile PBS (Amresco, USA). Once the PBS was removed, 5 ml TrypLE (Invitrogen, USA) was added, and the flask was then incubated for 3–5 min at 37 °C. Once the cells detached, media was added in order to deactivate the trypsin in the TrypLE solution. The mixture containing cells was transferred to a sterile tube, and centrifuged for 5 min at 1200 g. The suspension is then in two phases: the top of the vial being media and TrypLE, and the bottom being media and cells. The top phase was removed, and the cells are re-suspended in fresh media to the desired cell concentration, used in experiments, of approximately 60 000 cells/ml. Bovine serum albumin was added in the cell media to discourage cell agglomeration.

Human embryonic stem cells

H9 human embryonic stem cells were maintained by and obtained from StemCore, the Australian Stem Cell Centre’s core laboratory. For the trapping array runs, cells adapted to single-cell passaging with TrypLE (hereafter, “single cells”) were used. These were adapted from collagenase-passaged bulk cultures on mEF feeder layers. Cells were transferred to serum-free, feeder layer free conditions knockout serum replacement (KSR) media based on DMEM-F12 media, Matrigel attachment substrate) prior to use in the trapping arrays. Feeding of the cells was achieved by replenishing media daily until the cells were confluent. Once confluency was reached, the cells were passaged. To do so, the media was removed and then the attached cells were washed twice with sterile PBS (Amresco, USA). Once the PBS was removed, 5 ml TrypLE was added, and the flask was then incubated for 3–5 min at 37 °C. Once the cells detached, fresh media containing basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) was added in order to deactivate the trypsin in the TrypLE solution. The mixture containing cells was transferred to a sterile tube and centrifuged for 5 min at 470 g. The suspension is then in two phases: the top of the vial being media and TrypLE, and the bottom being media and cells. The top phase was removed, and the cells are re-suspended in fresh DMEM-F12, KSR media to the desired cell concentration. Then, a portion of the cells is transferred to a new flask with media, and then placed in an incubator at 37 °C with an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. Resulting cell suspensions used in experiments were around 10 000 cells/ml. Bovine serum albumin was added in the cell media to discourage cell agglomeration.

Chlorella algae cells

Green chlorella microalgae (2–10 μm diameter) were initially cultured in an incubator at 23 °C and kept in 18 h of light and 6 h of darkness. As cell densities increased, the suspensions were transferred to new flasks, which were kept agitated constantly in order to maintain the stock in suspensions. The solutions were incubated at 85 °C for sanitation and then were inoculated with F/2 media. Carboys were filled with 1 μm filtered, UV-sterilized seawater and hypochlorite and left for 24 h. The vessels were dechlorinated with thiosulfate stock solution and allowed to stand for an additional 4–6 h. All air was filtered to minimize contamination during culture. The carboys were inoculated with F/2 stocks A&B and sodium bicarbonate, NaHCO3, then swirled to dissolve the bicarbonate before being inoculated with algae culture. The carboys were continually swirled to maintain algae in the water column. After a few days, additional F/2 A&B stock was added and the aeration slightly increased. When cultures were 5–7 days old, cell densities were around 1 000 000 cells/ml.

Cell counting via hemocytometry

Cells were counted via hemocytometry. 20 μl of cell suspension was mixed with 20 μl of trypan blue and then, using a pipette, placed onto the hemocytometer glass slide. The viable and dead cells (dead cells are stained blue) for four of the large grids were counted and the amount of cells/ml was estimated by the approximation

| (1) |

where 5 is the number of grids or areas on the hemocytometer from which the cells were tabulated, 2 is the dilution factor from trypan blue, and 104 is the scaling factor (units of 1/ml) of the hemocytometer.

Polystyrene microspheres

Suspensions of polystyrene microspheres (20 μm diameter) in ethanol (Fischer-Scientific) were prepared at concentrations between 35 000 beads/ml and 500 000 beads/ml.

Numerical methods

2D numerical models were generated for generations 1 and 2 devices for all trap shape configurations to determine the channel velocity field and resulting shear stresses experienced by trapped cells at inlet velocities ranging from 0.001 to 10 m/s. The model for the cells or particles was a spherical, non-deformable body of size from 5 to 25 μm. The shear stress profile on the cell’s surface was generated for a variety of positions within the trap. Meshes were created by means of the solid modeler GAMBIT (Ansys, Inc., Canonsburg, PA, USA). Domains were discretised using a structured mesh of quadrilateral elements. The numerical simulations of the flow were performed using ansys 12.0.16 (ansys, 2009). This is a general-purpose commercial cfd package that allows the solution of the Navier–Stokes equations using a finite volume method via a coupled solver. Steady-state momentum and continuity equations for the fluid flow in the trap arrays were solved. The advection terms were discretised using an up-wind scheme with a second order correction to minimize numerical errors. Simulations were typically considered to have attained convergence as the normalised residuals for velocities and species fell below 1 × 10−7. Analyses were run on a linux cluster (1 node with 2 Quad-Core Intel Xeon processors, 8 GB RAM).

A uniform pressure condition (P = 0) was imposed at the inlet of the microchannel. No-slip boundary conditions were applied at all walls, while a uniform velocity profile normal to the cross sections was imposed at the outlet. De-ionised water was adopted as working fluid (ρ = 998 kg/m3, μ = 0.001 Pa·s).

A preliminary grid convergence study was carried out in order to verify that the solution was grid independent. In particular, the error on the inlet velocity profile was found to be less than 0.01 with increases of 10% in the number of cells. Therefore, a grid with approximately 104 elements was obtained (minimum elements size of 0.02 μm × 0.02 μm). Velocity maps and streamlines were plotted for the geometries analyzed and data concerning velocity and pressure distributions were extracted.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Optimisation of trap hydrodynamics through simulation

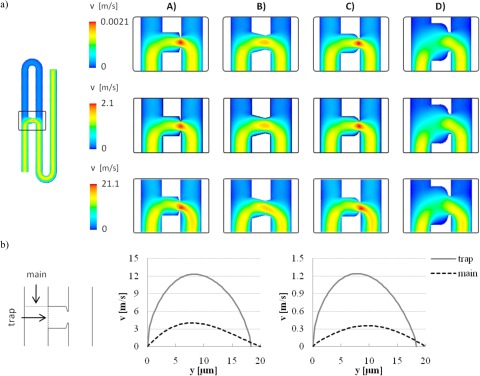

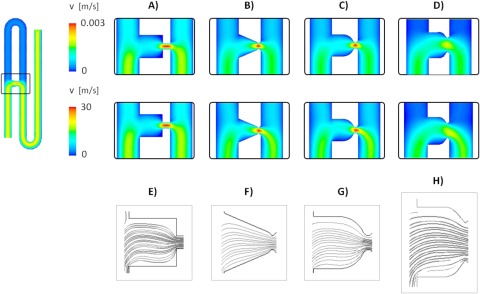

Simulation of fluid flow through the generation 1 trapping networks, shown in Fig. 2, confirmed the design dimensions permitted partitioned flow between the main channel and the trap channel, and further, preferential flow through the trap channel in the absence of any obstruction. The addition of a smaller channel to the trap exit is substantial in reducing the relative magnitude of velocities in the central regions of the trap, regardless of geometry, compared to inlet and outlet velocities (see Fig. 3). Different trap shapes, all having the same dimensional parameters in terms of depth, trapping channel lengths and widths, main channel lengths and widths, produce contrasting streamline plots, and the interaction of the fluid with the different geometries can produce areas of stagnated flow or distorted field lines, which may potentially trap cells or particles in unwanted positions, as well as cause aggregation and blockages. For example, in Figs. 3E–3H, it is evident that the tapering triangular structure creates a more focused streamline plot flow entering the trap, while the square, conical, and elliptical shapes cause greater distortion and nonlinear behaviour of the flow passing through the trap.

Figure 2.

(a) Velocity profiles for generation 1 hydrodynamic cell traps for the four analyzed geometries: A, square; B, triangular; C, conical; D, elliptical, for inlet velocities equal to 1 mm/s (top) 1 m/s (middle) and 10 m/s (bottom). (b) Flow partitioning between main channel and trapping channel for the square shaped trap for inlet velocities equal to 10m/s (left) and 1 m/s (right).

Figure 3.

Velocity profiles for second generation hydrodynamic cell traps for the four analyzed geometries: A, square; B, triangular; C, conical; D, elliptical, for a velocity of 0.001 m/s (top) and 10 m/s (bottom); streamlines within the trap for a velocity of 10 m/s for (E) square traps; (F) triangular traps; (G) conical traps; and (H) elliptical traps.

In general, from the data presented in both Figs. 23, varying the main channel (inlet) average velocity for the model from 0.001 m/s to 10 m/s does not substantially affect the velocity partition for the flow between the trap and the main channel. However, increasing inlet velocity up to 10 m/s slightly increases the ratio of fluid velocity through the trap and the main channel, respectively, but more noticeably, causes a shift and distortion of several microns in the location of the peak velocity in the trapping channel (Fig. 2b).

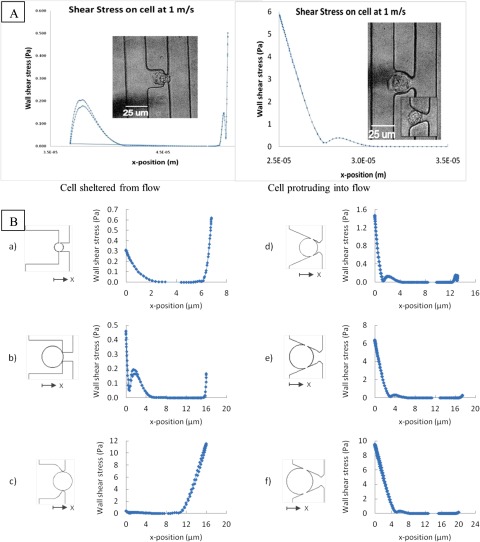

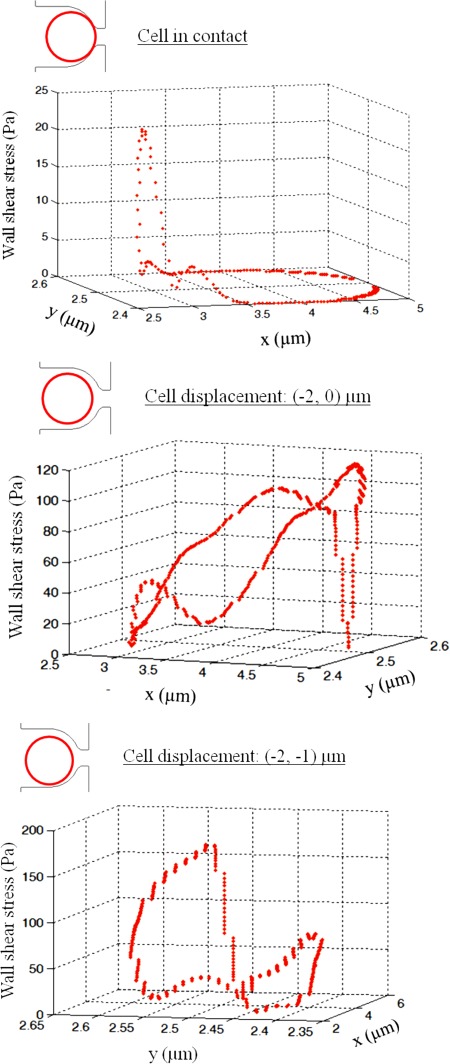

Cell stress analysis—Simulations

In order to assess the possible impacts of trap geometry and cell size on cell viability (across the three generations of devices investigated), additional computational analyses were performed considering individual circular particles with different dimensions sitting in the trapping channel in several positions to estimate the magnitudes of the shear stresses likely to be experienced at the surface of the trapped cells under the differing trap conditions, see Fig. 4. In the condition that the cell’s size is significantly less than the depth of the trap, a shearing fluid with a velocity of 1 m/s can induce a 1.5 Pa shear stress on the cell surface most proximal to the main flow (Fig. 4d). If the cell size is the same size as the trap such that the cell surface is tangent to the shear flow, the maximal stress experienced on the surface increases to 6.5 Pa (Fig. 4e), which is above the viability limit for most endothelial cells.20 When the cell surface protrudes into the flow, the shearing will increase to at least 10 Pa (Fig. 4f). Other conditions that increase the surface stress on the cell are described in Figs. 4a, 4b, 4c. As cell size decreases to the size of the trap exit, a parabolic distribution of stress across the surface dominates. If the cell is on the same size order as the trap exit (Fig. 4c), it will protrude into the main carrier flow, and thus experience a stress profile similar to Fig. 4f. Therefore, for a given trap configuration, there is an optimum trapping position, dependent on the ratio of cell size to trap size, for which the resulting surface stress will be minimal during the experiments. It should also be noted that for certain trap positions, the distribution of stress around the cell’s circumference is such that most of the cell (greater than 50%) experiences very little to no shear stress, even at high velocities around 1 m/s. In addition, the surface stress profile is symmetric, with both sides of the cell experiencing the same stress distribution.

Figure 4.

Cell surface shear stress distribution at 1 m/s carrier fluid velocity; (A) A cell surface (MSC pictured) completely sheltered from the carrier fluid (left picture) experiences significantly lower shear stresses than a surface at the trap entrance or protruding into the main flow (right picture); (B) resulting shear stress profiles across a cell surface for various cell sizes, trap geometries, and trapping configurations.

Since the fluid velocity profile becomes highly distorted at velocities exceeding 10 m/s, as shown in Figs. 2a and 3E–3H, there is a greater concern for non-ideal trapping schemes where individual cells are immobilized in the trap but not completely blocking the trap outlet channel. For example, if lateral motion of the trapped cell exposes the trapping channel by ±1 μm, the maximal shear stress on the surface will increase up to 450%, as seen in Fig. 5 (from 20 Pa to 110 Pa for 10 m/s inlet velocity). From the simulations, the cell position that results in the highest amounts of stress is when its surface was increasingly exposed to the main channel flow and when the trapping channel was not completely sealed by the cell. For example, when the cell is translated 2 μm off of the trap channel and 1 μm towards the main channel flow, the stress increases from 20 Pa to over 200 Pa. Additionally, the stress around the cell surface is not symmetric and more irregularly distributed. The highest velocities in the hydrodynamic traps occur through the trapping channel; thus, it is expected that the higher amounts of shear occur when that channel is only partially blocked by the cell, and fluid is still allowed to pass through.

Figure 5.

Shear stress distribution on a spherical cell surface in a hydrodynamic trap based on location in the trap at inlet velocity of 10 m/s.

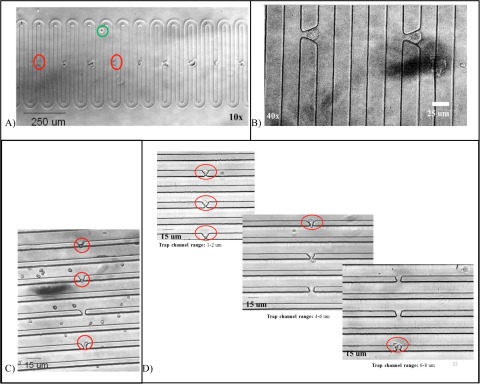

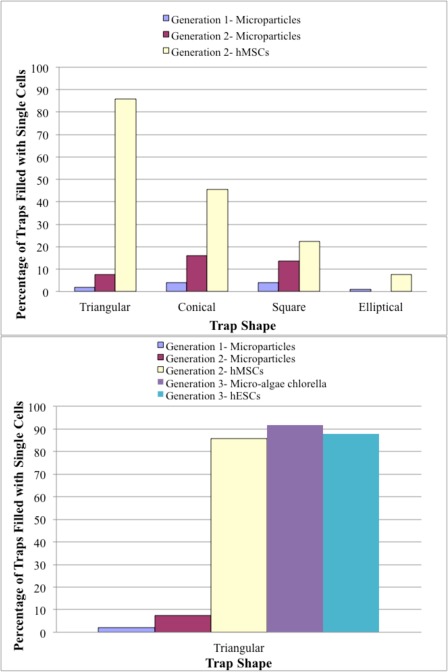

Single microparticle capture

For targeting single, spherical 20 μm polystyrene microparticles, particulate suspensions were perfused through the devices at velocities of 4 mm/s. For generation 1 devices, the majority of traps remained empty within 30 min of operation at flow rates around 4 mm/s. The highest number of filled traps for the 30 min period was recorded for the triangular array (32% filled at 30 min) and the lowest was the elliptical array (<5% at 30 min), as reported in Fig. 6. Comparatively, when the generation 2 devices were run at the same velocities, 5%–10% increases in the amount of filled traps was noticed across all trap geometries over shorter term (5–10 min) experiments. This is attributed to the smaller channel at the trap exit in generation 2 devices in comparison with those in the generation 1 devices. In generation 1 devices, it was observed that the larger trap exit, combined with the high velocity magnitude, facilitated the microparticles in passing through the trapping channel rather than remaining lodged. Also, it was observed that the larger trap exits permitted multiple particle trapping, mainly in conical, square, and elliptical geometries (Figs. 7B, 7D, 7E, and 7G), which led to aggregation and subsequent channel clogging.

Figure 6.

(A) Percentage of 20 μm polystyrene microparticles captured in generation 1 devices at v = 4 mm/s after 30 min; (B) percentage of 20–25 μm human mesenchymal stem cells captured in generation 2 devices at v = 4 mm/s, after 15–20 min; and (C) percentage of algae cells captured in generation 3 devices at v = 0.1 mm/s and v = 0.2 mm/s after 10 min.

Figure 7.

Single microparticle capture in generation 1 devices: (A) triangular arrays, (B) elliptical arrays, (C) triangular arrays, (D) elliptical arrays, (E) conical arrays, (F) square arrays, and (G) particle aggregation at square traps.

Across generations 1 and 2 devices, the elliptical trap displayed the lowest occupancy, with generally less than 10% being filled over a 5–10 min interval. Moreover, for both generations, the conical and square shapes captured 2%–10% more single particles than the triangular array over the shorter, 5–10 min trapping experiments. However, for trapping experiments lasting 15–20 min, there was a sharp change in efficiency, with triangular traps capturing 8%–30% more single particles than any other trap shape, whether they be square, conical, and elliptical traps. Overall, the triangular trap array was the most consistently reliable in filling large amounts of traps with single microparticles (Figs. 7A and 7C). It should be noted that the percent occupancy differences between the four traps shapes are also partially a result of factors irrespective of shape such as microchannel clogging from random occurrences of particle aggregation in the device. With increasing ratios of trap area to particle area, the selection for two or more particles increases from almost zero to 75% in generation 1 devices. This increasing trend is also associated with a higher percentage of empty traps (68%–98%). These results match similar values in the literature.11

As mentioned previously, a critical aspect that drastically influenced the reproducibility of microfluidic particle trapping systems is particle aggregation resulting in channel blockages. In fact, the impact of one array becoming blocked in a device that has 4 arrays in parallel (see Fig. 1) is substantial. A single blockage in one channel will cause the fluid velocities in the remaining arrays to increase because of the redistribution of pressure through the device. Sometimes clogs will resolve themselves, because the pressure drop eventually increases enough to force the blockage to break up or continue downstream to the device outlet, but this occurs unpredictably, and often times instead, the device will develop leaks or simply fail. Also, the various velocity changes associated with the fluctuations between particle aggregation and deglommeration can encourage more particle blockages. In these cases, the total percent occupancy achieved over any time period of these devices can then remain extremely low. Although particle aggregation within the trap arrays was decreased as a result of the generations 1 and 2 devices evolution, through tailoring the trap hydrodynamics, the trap geometries, and the device layouts, the overall percent occupancy achieved was still hampered at times by other blockages that occurred primarily at the device inlet. It should also be noted that the high percentage of blockages and clogging with polystyrene microparticles can be largely attributed to the fact that the microspheres are nondeformable particles.

Single-cell capture

Mesenchymal stem cells

When the suspensions of MSCs were perfused through generation 1 devices at 4 mm/s, cells were easily able to deform through the trapping networks, even when cells were twice the size of the trapping channel (i.e., 20 μm cell through 10 μm trapping channel). Single MSCs were successfully arrayed in generation 2 devices, which contained trapping channels that were 40%–60% smaller than the generation 1 devices. Single MSCs were captured at velocities of 4 mm/s in generation 2 devices, with over 85% of triangular traps filling with single cells within 10 min, see Fig. 6. Again, the elliptical arrays performed the worst, filling to only 13% occupancy with single cells. As observed with the polystyrene microparticles, the number of traps with single cells decreased with increasing trap-to-cell size ratio, indicating that the size of the traps can be used to tune the efficiency of single cell trapping devices based on the size of the cells. Although the cells and microparticles are similar in density and size, MSCs, being adherent, tissue cells, are deformable and elastic materials that have adhesive surfaces and can thus form aggregates. This deformability is advantageous, in terms of being able to “squeeze” past blockages, but their adhesive properties are disadvantageous in that cells can easily aggregate together and be captured in multiples in a single trap. However, with suitable upstream treatment of the cell suspensions in terms of transient removal of surface proteins to avoid any aggregates prior to injection into the device, this can be substantially moderated.

A decrease in trap width by 5–10 μm (e.g., 15–7 μm trapping channel width for the triangular array) can target the specific species (20 ± 5 μm MSCs), confirmed by the increase in single-cell occupancy from 0% to almost 90% in 5–10 min. This also indicates that the requirement for trapping channel width is dependent on the physical properties of the species. For example, the triangular trap in generation 2 devices captured 80% more single MSCs than single polystyrene microparticles. This trend is consistent with all of the trap shapes: more single MSCs are trapped than single microparticles in the same device. However, the conical trap only saw an improvement of 30%, the square trap around 8%, and the elliptical trap only 6%. The same hierarchy in efficiency with regards to trap shape is visible in the studies with particles in both generation 1 devices, where triangular arrays achieved >95% of filled traps having single particles, whilst the conical, square, and elliptical traps achieved 93%, 78%, and 25%, respectively. Figs. 8A and 8B show the individually arrayed MSCs in triangular traps at various magnifications.

Figure 8.

Trapped and arrayed mesenchymal stem cells imaged by phantom v. 5 high speed camera on a Nikon confocal microscope at (A) 10x, (B) 40x, (C) chlorella algae cells in triangular traps, and (D) increasing size of trap aperture arrays fewer single human embryonic stem cells.

Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs)

hESCs were captured in generation 3 devices at slower velocities of around 0.1 mm/s, filling devices to 85% occupancy with 100% of the occupied traps hosting single cells within 10–15 min. These cells require trapping time scales of 20 min or less before the cells become visibly distressed. A further indication of these devices being used in cell size selection, three different trap arrays with different trap channel widths were investigated with the hES cells. With increasing trap channel widths (from 1 to 8 μm), the amount of filled traps with single cells decreased drastically (80%–40%), as cells were both able to be filtered through traps and be captured as multiple cell aggregates, see Fig. 8D. This is in-line with the observed results for the MSCs and microparticles and further confirms this device’s precision in size selection to the order of microns.

Algae cells

For green chlorella algae cells, generation 3 devices filled to 92% occupancy with 77% of the filled traps containing single algal cells in 10 min at 0.1 mm/s (Figs. 6 and 8C). Higher percentages of traps with multiple cells (increasing from 0% to 18%) and of empty traps (increasing from 0% to 32%) were achieved when the withdrawal syringe pump flow rate was adjusted from 0.1 mm/s to 0.2 mm/s. This demonstrates that higher fluid velocities can decrease the single-cell percent occupancy of the devices, because there is a higher probability that cells will collide with each other within the carrier fluid, forming aggregates and trapping as multiples. Also, it should be noted that since cells are not rigid particles, a substantial carrier velocity can force the cells through the trapping channels, effectively deforming the cell’s membrane enough, so it is able to pass through the trap.

Fig. 9 shows the comparison of trapping devices for microparticles and cells for experiments lasting 5–10 min. It is clear that the particles and cells behaved quite differently across the generations, suggesting that the physical property of the species significantly impacts the trapping success or percent occupancy of the hydrodynamic arrays. In particular, for rigid bodies, such as polystyrene microparticles, clogging can easily nucleate in the small channels, while tissue cells are deformable and can be forced to move through small channels. Collisions between adherent cells in a flow can promote aggregation, but the overall physical properties remain the same. For materials such as polystyrene, electrostatic, or hydrophobic forces may also be a consideration in their increased propensity to agglomerate.

Figure 9.

Cross-generational device comparison for trapping experiments.

In terms of the possible impacts of shear forces on cell viability at extremely high carrier velocities (ranging up to m/s), referring to Fig. 4, across all device generations, we note that the square traps is the geometry where isolated MSCs are likely to experience the lowest shear stress of 0.4–0.6 Pa (at average velocities of 1 m/s). In contrast, whilst triangular shaped arrays were certainly the most efficient at immobilizing large arrays of individual cells or particles, these geometries, along with the conical shaped traps, tended to position the cells to experience 1.5–12 Pa, which, at a velocity of 1 m/s, is a range that reaches above the acceptable stress limit of maintaining human endothelial cells and algal cells.20, 21Although the square traps were predicted to be the best shapes for minimizing shear forces on MSCs, these geometries had 40%–60% lower filling efficiencies for single-cell capture than the triangular traps.

CONCLUSIONS

A detailed numerical and experimental investigation into the optimisation of hydrodynamic micro-trapping arrays for high-throughput screening and selection of single polystyrene microparticles and three different types of live cells at trapping times of 30 min or less has been described. We investigated the relative impacts on percent occupancy of the trapping arrays for four different trap geometries (triangular, square, conical, and elliptical) within three different device generations, in which device architecture, channel geometry, inter-trap spacing, trap size, and trap density were varied. Through numerical simulations, we first confirmed that the calculated device dimensions permitted partitioned flow between the main channel and the trap channel, and further, preferential flow through the trap channel in the absence of any obstruction. Second, we showed that the different trap shapes, all having the same dimensional parameters in terms of depth, trapping channel lengths and widths, main channel lengths and widths, do not impact the velocity magnitudes or the net direction of the field lines but do affect the degree of flow confinement and can cause distortion of the field lines; an outcome that may potentially trap cells or particles in unwanted positions, as well as cause aggregation and blockages. Last, our numerical investigation suggests that once trapped, any motion of the trapped particle or cell or a shift in its configuration within the trap will result in pressures on the cell surface increasing by 400%–450% and that the shear stress distribution across the cell’s surface exponentially decays as the cell becomes smaller than the trap, but a parabolic distribution of stress dominates as the cell approaches the size of the trap channel. Numerical outcomes were then validated experimentally with respect to the impact of these variations in device design elements on the percent occupancy of the trapping array (with one or more particles of cells) within these targeted short timeframes (<30 min). Limitations in obtaining high trap occupancies with initial device designs were overcome by optimisation of device design elements and other operational variables, such as the average carrier fluid velocity. MSCs, hESCs, and algae single cells were successfully arrayed at 85%, 100%, and 77%, respectively, in 10–15 min using optimised designs. These short time frame trapping outcomes are significant when considering that hESCs became apoptotic for trapping experiments longer than 20 min, while MSCs maintained their integrity over this same amount of time. Microalgal cells could remain on-chip for a period of several days without change in media, demonstrating a lesser need for high-speed trapping. For polystyrene microparticles, the maximal percent occupancy reached was 32%, as particle aggregates formed easily at high speeds, exemplifying the significant difference between outcomes for commonly utilised “model” cells (i.e., PS microparticles) and real living cells and the importance of using the target cell type for optimisation of cell-trapping devices. This investigation showed that in microfluidic single cell capture arrays, the trap shape that maximizes cell viability (square) is not necessarily the most efficient for high-speed single cell capture (triangular). However, high-speed trapping configurations for delicate mammalian cells are possible, because our models indicate that cells can be trapped in certain positions in which the resulting stress levels are in a viable range even at carrier fluid velocities greater than 1 m/s. However, the devices must be optimised for each cell type and designed principally in accordance with the trap size to cell size ratio.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors of this paper would like to acknowledge Dr. Peer Schnek and Dr. Holger Schuhmann of the UQ Algae Biotechnology group for the donated algae samples. Funding for this work was made possible by the UW-UQ Trans-Pacific Fellowship from the University of Washington, the Stem Cells Australia Special Research Initiative of the Australian Research Council, as well as the Tissue Engineering and Microfluidics Lab at the Australian Institute of Bioengineering and Nanotechnology.

References

- Lutolf M. P., Gilbert P. M., and Blau H. M., “ Designing materials to direct stem-cell fate,” Nature (London) 462, 433–441 (2009). 10.1038/nature08602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Chen Z. Z., and Li Q.-L., “ Microfluidic techniques for dynamic single-cell analysis,” Microchim. Acta 168, 177–195 (2010). 10.1007/s00604-010-0296-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ino K. et al. , “ Cell culture arrays using magnetic force-based cell patterning for dynamic single cell analysis,” Lab Chip 8, 134 (2008). 10.1039/b712330b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodkowic D., “ Microfluidic single-cell array cytometry for the analysis of tumor apoptosis,” Anal. Chem. 81, 5517–5523 (2009). 10.1021/ac9008463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlo D. D., Wu L. Y., and Lee L. P., “ Dynamic single cell culture array,” Lab Chip 6, 1445 (2006). 10.1039/b605937f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman G. T., Chen Y., Viberg P., Culbertson A. H., and Culbertson C. T., “ Single-cell manipulation and analysis using microfluidic devices,” Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 387, 9–12 (2006). 10.1007/s00216-006-0670-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Kim M.-C., Marquez M., and Thorsen T., “ High-density microfluidic arrays for cell cytotoxicity analysis,” Lab Chip 7, 740 (2007). 10.1039/b618734j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sia S. and Whitesides G. M., “ Microfluidic devices based on poly(dimethylsiloxane) for biological studies,” Electrophoresis 24, 3563–3576 (2003). 10.1002/elps.200305584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanyeri M. Johnson-Chavarria E. M., and Schroeder C. M., “ Hydrodynamic trap for single particles and cells,” Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 224101 (2010). 10.1063/1.3431664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz B. R., Chen J., and Daniel T. S., “ Hydrodynamic tweezers: 1. Noncontact trapping of single cells using steady streaming microeddies,” Anal. Chem. 78, 5429–5435 (2006). 10.1021/ac060555y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frimat J.-P. et al. , “ A microfluidic array with cellular valving for single cell co-culture,” Lab Chip 11, 231 (2011). 10.1039/c0lc00172d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobel S., Valero A., Latt J., Renaud P., and Lutolf M., “ Optimization of microfluidic single cell trapping for long-term on-chip culture,” Lab Chip 10, 857 (2010). 10.1039/b918055a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W. H. and Takeuchi S., “ A trap-and-release integrated microfluidic system for dynamic microarray applications,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 1146–1151 (2007). 10.1073/pnas.0606625104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson H., “ Microtechnologies and nanotechnologies for single-cell analysis,” Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 15, 44–49 (2004). 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J. et al. , “ Stepwise increasing and decreasing fluid shear stresses differentially regulate the functions of osteoblasts,” Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 3, 376–386 (2010). 10.1007/s12195-010-0132-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cioffi M. et al. , “ A computational and experimental study inside microfluidic systems: The role of shear stress and flow recirculation in cell docking,” Biomed. Microdevices 12, 619–626 (2010). 10.1007/s10544-010-9414-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M.-C. and Klapperich C., “ A new method for simulating the motion of individual ellipsoidal bacteria in microfluidic devices,” Lab Chip 10, 2464 (2010). 10.1039/c003627g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohles S. S., Neve N., Zimmerman J. D., and Tretheway D. C.,“ Mechanical stress analysis of microfluidic environments designed for isolated biological cell investigations,” J. Biomech. Eng. 131, 121006 (2009). 10.1115/1.4000121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J. V. et al. , “ Effect of channel geometry on cell adhesion in microfluidic devices,” Lab Chip 9, 677 (2009). 10.1039/b813516a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimmeler E. A., “ Shear stress inhibits apoptosis of human endothelial cells,” FEBS Lett. 399, 71–74 (1996). 10.1016/S0014-5793(96)01289-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michels M. H. A., Goot A. J., Norsker N.-H., and Wijffels R. H., “ Effects of shear stress on the microalgae Chaetoceros muelleri,” Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 33, 921–927 (2010). 10.1007/s00449-010-0415-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varde N. K. and Pack D. W., “ Microspheres for controlled release drug delivery,” Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 4, 35–51 (2004). 10.1517/14712598.4.1.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]