Abstract

Dielectric particles flowing through a microfluidic channel over a set of coplanar electrodes can be simultaneously capacitively detected and dielectrophoretically (DEP) actuated when the high (1.45 GHz) and low (100 kHz–20 MHz) frequency electromagnetic fields are concurrently applied through the same set of electrodes. Assuming a simple model in which the only forces acting upon the particles are apparent gravity, hydrodynamic lift, DEP force, and fluid drag, actuated particle trajectories can be obtained as numerical solutions of the equations of motion. Numerically calculated changes of particle elevations resulting from the actuation simulated in this way agree with the corresponding elevation changes estimated from the electronic signatures generated by the experimentally actuated particles. This verifies the model and confirms the correlation between the DEP force and the electronic signature profile. It follows that the electronic signatures can be used to quantify the actuation that the dielectric particle experiences as it traverses the electrode region. Using this principle, particles with different dielectric properties can be effectively identified based exclusively on their signature profile. This approach was used to differentiate viable from non-viable yeast cells (Saccharomyces cerevisiae).

INTRODUCTION

Single-cell analysis can provide insight into the mechanisms governing normal cellular growth and development. This is important because, for instance, the disruption of intracellular processes can lead to diseases.1, 2 In recent years, dielectrophoresis (DEP) emerged as a powerful and convenient approach to analysing and characterizing single cells. First described by Pohl3, 4 as a phenomenon in which forces are induced by a non-uniform electric field on neutral particles, it has over the years developed into a technique that can be used to characterize, sort, separate, isolate, and manipulate biological cells—see Refs. 5, 6 and references therein. Most notably, DEP method is label-free, since the information about cells is obtained based exclusively on their inherent electrical properties. To date, DEP has been used in blood analysis,7 including characterization of human red blood cells based on the blood type,8 sorting and concentrating the target microbe from a flowing blood sample,9 and isolation of red blood cells affected by malaria.10 By exploiting subtle differences between the healthy cells and their malignant counterparts, DEP can be employed to successfully isolate different cancerous cells11 and separate them from healthy ones,12 identify different types of cultured tumor cells,13 quantify electric properties of drug-resistant breast cancer cells,14 or study key stages in apoptosis of leukemia cells.15 Close connection between electrical properties of biological cells and their physiological and metabolic properties is often exploited to separate viable from non-viable cells,16, 17 but it also makes DEP a useful tool in studying stem cells,18, 19, 20 sorting out multiple different species of bacteria21, 22, 23 and subpopulations within the same bacterial species,24 or in characterizing plant protoplasts, yeast and algae.25, 26

A considerable number of DEP techniques are used in conjunction with microfluidics to probe and characterize the electrical properties of cells and their response to the electric field. Interestingly enough, few studies utilize electronic approach, and if they do, it is often combined with optical detection, or with analyses that require additional specific molecules for labeling and the appropriate pre-treatment.27, 28, 29

In this work, we discuss a system for an all-electronic detection and actuation of cells (and other dielectric particles) at high throughput. The procedure is completely label-free and requires minimal amount of preparation. In addition, analysis is done in a non-invasive manner and is perfectly suitable for miniaturization and completely automated analysis, making it a low-cost alternative with a great potential for application in both biomedical research and health care.

This paper specifies how to utilize dielectric response of a particle to a non-uniform ac electric field in order to probe the particles electronically. Material is organized as follows: the presentation of the appropriate background is followed by the explanation of the apparatus used for simultaneous detection and actuation; next, experimental results are related to the physical background, using simulations in order to calibrate the system. This is followed by a “catalogue” of electronic signals and the explanation of the kind of information that they contain; particle tracking is used to supplement this information and to provide the initial conditions for a numerical simulation of a particle trajectory. Finally, results are applied to a simple biological system, the Brewer’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), in order to illustrate the ability to discriminate between viable and non-viable cells.

BACKGROUND

The dielectric response of particles to electric fields can be exploited to both detect and actuate cells suspended in solutions in a laminar flow through microfluidic channels.30, 31 When a dielectric particle traverses the electrode region, a polarization P is induced within the particle volume as the microscopic charges inside separate and dipoles orient under the influence of the external field. This local reorganization results in changes in the electrical energy density within the dielectric particle and can be registered macroscopically as an impedance variation as the particle moves through the region of the electric field. Assuming that the dielectric particle is uniform, isotropic, and spherical, polarization P will be simply proportional to the external electric field E32

| (1) |

where is the field induced inside the particle volume. Quantities where are the complex dielectric permittivities of the particle (p) and the medium (m) it is suspended in. They involve both dielectric polarization effects (through dielectric permittivity ) and losses (through conductivity ) at different frequencies ω. (Note that the multiplying in Eq. 1 is not a complex quantity.33) Quantity is the Clausius-Mossotti factor,

| (2) |

Equation 1 holds in general, for both stationary and time-changing fields; this work concentrates on the latter and assumes a changing electric field of the form . If, in addition to the conditions given above, the particle is small compared to the channel, it may be assumed that the field is uniform over the entire volume of the particle. This last assumption allows the change in energy (time-averaged over a period of the electric field oscillation, as denoted by “”), resulting from the particle passing over the electrodes and stored in the particle-channel system, to be expressed as

| (3) |

In the above, V is the volume of the particle, represents the real part of the complex quantity is a complex conjugate of P, and is the rms value of the external field at the center of mass of the particle. Dielectric particles flowing above the electrodes cause a perturbation in the capacitance of the analysis volume, , so that , where is the rms value of the potential applied to the electrodes (such that ). Finally, the (average) change in capacitance can be expressed as

| (4) |

In a non-uniform field, a polarized dielectric particle moves along the field gradient. This phenomenon, termed DEP, occurs because the non-uniform field results in unequal forces on the charges separated by polarization. The resulting net force can be expressed as33

| (5) |

It is obvious from Eq. 5 that the sign of the DEP force, and therefore the direction in which the dielectric particle is actuated, does not depend on the polarity of the field, but is instead determined by the sign of the dielectric contrast between the particle and the medium, . Therefore, both the direction and magnitude of actuation depend on the specific dielectric properties of the particle suspended in a given medium. Furthermore, through , both sign and magnitude of depend on the field frequency. This makes DEP especially useful for manipulating particles like biological cells whose properties vary with their ionic content, often in close relation to their developmental stage or state of health.

DETECTION AND ACTUATION

The apparatus described here is unique in that it probes the dielectric properties of individual particles via simultaneous detection and actuation. A schematic illustration is provided in Fig. 1a. Using pressure-driven flow, individual particles are pumped into a tall interrogation channel, which houses coplanar electrodes fabricated on the channel floor. These electrodes are connected to an all-electronic detection-and-actuation system. The channel length, height, and width are measured along the x, y, and z axes, respectively. The coordinate origin is situated on the channel floor (x–z plane), at the intersection of the perpendicular bisectors of the central electrode.

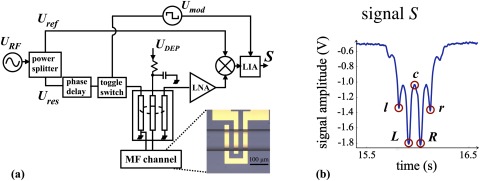

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic representation of the microwave interferometer (see Ref. 34 for full description) used to simultaneously detect and actuate particles. Electronic signatures were collected as PSS flowed through the microfluidic (MF) channel and over the two-gap electrode array (shown in the inset micrograph). (b) A characteristic signature, S, is proportional to and depicted here for a spherical particle passing above the two-gap electrode array. For a given elevation, the field is always stronger above the electrode edges than at their centres; therefore, peaks in signature S correspond (approximately) to the time instants when particle is directly above an electrode edge. Specifically, L and R are the peaks corresponding to the left and right edges of the central electrode, c is the trough corresponding to its middle, and l and r are peaks corresponding to the inner edges of the left and right electrode, respectively. The left-to-right symmetry of the signal indicates that the particle elevation does not change during its flow through the analysis volume.

Detection

The detection sensor is a microwave interferometer that has been described in detail previously.34 Briefly, an RF signal (in the gigahertz range, modulated at 100 kHz), supplied by the signal generator, , is split in two paths: the reference path, , is left unmodified, and the sensing path, , passes through a 1.45 GHz microwave resonator, which is connected to the coplanar electrodes. The electrodes create a non-uniform field in the channel volume directly above, hereafter referred to as the analysis volume. Particle detection is effected as a result of a change in the phase difference between the two paths, and , generated by the passage of the particle through the analysis volume.

As shown in Fig. 1a, the resonance path is amplified and then mixed with the reference path . The phase delay between the two paths is initially set to radians, so that the two paths interfere destructively when there are no particles in the analysis volume; this provides a baseline. Any additional phase difference between the two paths is, therefore, brought about by the change in capacitance, resulting from the particles passing over the electrodes. This phase difference is detected by the lock-in amplifier (LIA) and translated into the signal S (in volts) approximated by34

| (6) |

Here, G is the overall system gain, and are the amplitudes of the reference and resonant paths fed into the mixer, and is the rate of change of phase with respect to the change of capacitance at the resonant frequency —see Ref. 34 for details.

Evidently, the signal S is proportional to via the change in capacitance (Eq. 4). The characteristic signature of an unactuated sphere is reproduced in Fig. 1b. The varying amplitude of the signature directly correlates with the varying strength of the electric field above the specific regions of the two-gap electrode array. The field is strongest at the electrode edges, and thus the four most prominent peaks (labelled l, L, R, and r) correspond to the inner edges of the electrode array, as shown in Fig. 2. However, because also varies with elevation, any changes in the vertical trajectory of the cell will register on the amplitude of S.

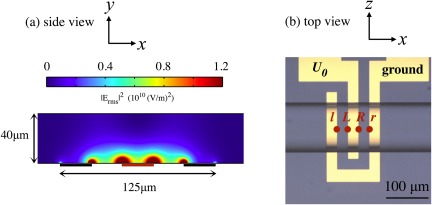

Figure 2.

(a) in the vertical x–y plane along the centre of the microfluidic channel, as obtained using comsol®multiphysics. These simulations confirm that the electric field is most intense at the electrode edges. (b) The peaks l, L, R, and r correspond approximately to the horizontal locations of the electrode edges, shown here in the micrograph looking down at the channel. The position of the central trough, c, is not explicitly labelled here, but follows as the midpoint between L and R.

Actuation

To actuate particles as they flow through the analysis volume, an additional path—labelled in Fig. 1a—is used to deliver a low frequency signal (100 kHz–20 MHz) across the same coplanar electrodes used for high-frequency detection. Because high (gigahertz) and low (kilohertz to megahertz) frequency ranges are highly disparate, detection and actuation signals are uncoupled and can be applied simultaneously.

As explained in Sec. 2, any dielectric particle immersed in a non-uniform electric field will experience DEP–an electrical force that acts along the field gradient. In response, the particle moves up or down the field gradient (depending on whether the particle or the surrounding medium is the more polarizable domain) and its elevation changes. The high-frequency detection signal is sensitive to particle elevation. Consequently, when a low-frequency DEP signal is applied to a particle flowing through the analysis volume, the resulting elevation changes are readily detected via changes in amplitude of S. It follows that the capacitance signatures of single cells depend greatly on the applied DEP force.

It is important to emphasize that we measure the particle response to DEP forces in an indirect way. Essentially, a high-frequency signal captures the cell response to low-frequency actuation, but the variations in the high-frequency capacitance signature emerge purely from changes in particle position, as influenced by the low-frequency DEP force. It is also important to note that although both low and high frequency signals can induce DEP, only the low-frequency signal changes the particle position in a detectable way. As part of the apparatus design, magnitude of the gigahertz (“high”) frequency field is kept intentionally low (), rendering the corresponding DEP force at least an order of magnitude weaker than its low-frequency counterpart ().

In conclusion, the advantage of simultaneous detection and actuation comes from the contrasting dielectric responses of the cell in two distinct frequency regimes. Between 100 kHz and 20 MHz, both the sign and the magnitude of the DEP force are sensitive to the ionic composition of the biological cells (see, e.g., Ref. 35 and references therein), which is directly related to the metabolism and physiological properties of the cells. Consequently, kilohertz to megahertz DEP force variations provide a way to successfully identify cells. Conversely, at gigahertz frequencies, the influence of ionic composition is minimal; instead, the permittivity (), which reflects the cell type, governs the detected signal. Using a combination of cell responses from two distinct frequency regimes allows for detection of subtle modifications in the electronic signatures of the cells. This ultimately provides a powerful technique for discriminating between subpopulations of cells (characterized by different ionic composition) within a large population of similar cells (all of which have the same permittivity, ).

SIMULATIONS

Both detection and actuation mechanisms can be modeled by computer simulations of a single sphere with known material properties. The sphere of radius a is assumed to be suspended in a solution whose properties are also known and set in a Poiseuille flow through the rectangular channel of height H, passing above the electrodes at different elevations . The simulation conditions were matched to the experimental ones, where polystyrene (PS) spheres were used as model particles with following dielectric properties:

| (7) |

| (8) |

In the above, is the (real) absolute permittivity of free space, (Refs. 36, 37), and is the surface conductivity of PS (Refs. 38, 39, 40). (For 1 MHz and above, for a —diameter PSS is always negative. Detailed plots of for different frequencies and sphere radii can be found in Ref. 38.) The spheres were suspended in deionized (DI) water, with known permittivity and with measured conductivity . All simulations were carried out using cosmol® multiphysics software.

To simulate a detection signal, it is enough to simulate the ratios This is accomplished by numerically solving the Laplace equation with appropriate boundary conditions, where φ is the electric scalar potential, and . The change in capacitance, is obtained by multiplying the by the factor which, for a diameter PSS in DI water, is at gigahertz frequencies. Since the signal, S, is proportional to (Eq. 6), experimentally measured signals will closely resemble the change in capacitance profiles and the simulated ratios and will depend on the particle elevation through these ratios. The system can then be calibrated by appropriately scaling the simulated ratios and comparing them with the experimentally obtained signals. An example of this procedure will be provided in Sec. 5.

Actuation is simulated by generating a trajectory of a particle assumed to be a point mass and subjected to time-averaged forces acting at that point. Specifically, the particle is assumed to be subjected to a DEP force, given by Eq. 5, and a fluid drag force,

| (9) |

Here, η is the viscosity of the fluid medium, a is the radius of the spherical particle, and and are the particle and fluid velocities, respectively. Assuming the fluid establishes Poiseuille flow with average flow speed , its velocity, (where is a unit vector in the x direction), at a given elevation within the channel (of height H) is given by

| (10) |

While particles flow outside the analytic volume their elevation is mainly governed by gravity, buoyancy, and hydrodynamic lift.41 In a laminar flow, particles sediment rapidly on the timescale of the experiment and establish an equilibrium position where the apparent weight, , (representing a difference between gravity and buoyancy) and hydrodynamic lift force, FL,42, 43 are equal

| (11) |

In the above expression, and are the (average) densities of the particle and the medium, is gravitational acceleration, and η is the viscosity of the medium. The lift force constant, , can be determined empirically. From Eq. 11, it follows that

| (12) |

Numerical value of can be obtained by applying the empirical conditions of an unactuated PSS. Assuming that an unactuated PS () sphere of radius establishes a equilibrium elevation within a Poiseuille flow () of DI water (), the value of the lift force constant in a high channel is found to be

The trajectory of an actuated particle is calculated by first assuming the velocity of the particle at a given elevation to be equal to the velocity of the fluid layer at that elevation, and then calculating subsequent positions and velocities of the particle at each time step as the particle moves under the influence of . The trajectory of a diameter PSS, entering the analysis volume at the and with a horizontal velocity of , and experiencing DEP forces resulting from a applied potential at 1 MHz, is shown in the inset of Fig. 3. As the PSS enters the electrode region, it encounters the DEP force, whose components are plotted in the same figure. While the vertical component always acts in the same direction, repulsing the particle from the electrodes and thereby increasing its elevation, the horizontal component switches the direction abruptly at each electrode edge. Both forces progressively diminish as the particle is deflected to higher elevations.

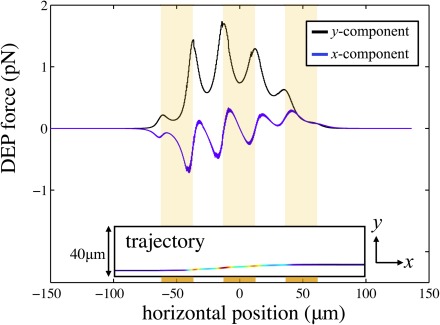

Figure 3.

Horizontal (x) and vertical (y) components of a simulated DEP force, which acts on a PSS initially flowing at an and horizontal velocity. Superimposed shaded areas represent the horizontal extent of the three electrodes and were added to make it easy to recognize that the vertical DEP force is strongest at the electrode edges. Outside the electrode region, DEP force quickly falls away to zero. The region of acceleration is restricted to in the horizontal direction. The inset below the force plots depicts a vertical cross-section (x–y plane) through the microfluidic channel, which contains the trajectory that an actuated PSS follows as it passes through the analysis volume. The colour along the trajectory represents the intensity of the y component of the DEP force on the PSS: dark blue corresponds to no force and deep red to the maximum force intensity of 1.74 pN.

For this example, apparent gravity, lift, and drag are all on the order of femtonewtons, and the DEP force clearly plays a dominant role in accelerating the particle. Outside of the analysis volume, however, it quickly falls away to zero, so that the region of particle acceleration covers the interval , as evident from the plot in Fig. 3.

SYSTEM CALIBRATION

Although the signal S is proportional to the ratio the overall coefficient of proportionality is unknown and needs to be determined via calibration. This involves matching the simulations to the experimental signals produced by a set of model particles—in this case, polystyrene spheres (PSS). While collecting experimental data, the apparatus-based proportionality factors (A in Eq. 6) are constant, and the dielectric contrast between the suspending medium and the model particle is known. Therefore, two particle parameters, size and elevation, can vary the signal amplitude.

The PSS are spherical and uniform in size, but not identical (. Consequently, at a given elevation, larger particles will induce larger capacitance changes. At the same time, this error source is somewhat counterbalanced because larger particles equilibrate at higher elevations compared with those of smaller particles (cf. Eq. 11). To minimize the effect of particle size to the signals amplitude, the system is calibrated by comparing the amplitude ratios of simulated signals to those of experimental signals. The best ratio to choose for this purpose is the one between the features that are most- and least-sensitive to particle elevation h. As can be observed from simulations of an unactuated signal (Fig. 4), this is the ratio between the average of the peak amplitudes at L and R, and the central minimum amplitude at c (see Fig. 1b).

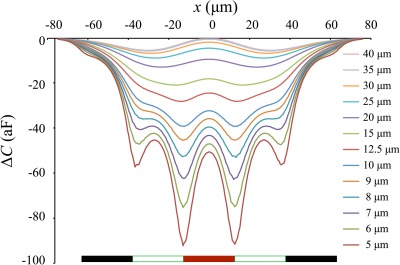

Figure 4.

Simulated capacitance signatures, , as induced by a diameter PSS flowing past the electrode array with different constant elevations . The electrode positions (black-red-black, separated by gaps of equal width) are indicated on the bottom of the figure.

Ideally, amplitudes L and R should be identical, but they rarely are in practice. Even slight changes in particle elevation (caused, for example, by Brownian motion) or small variances in electrode shape or thickness due to fabrication will translate into small variations between the corresponding peaks. For this reason, the average peak amplitude, (L + R)/2 is used.

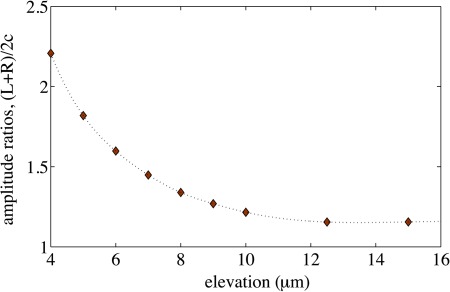

The ratios (L + R)/2c for different particle elevations, represented in Fig. 5, were extracted from simulations (Fig. 4). Once the system is properly calibrated in this way, the elevation of any particle at the time of measurement can be estimated, by interpolation, using the corresponding ratio obtained from its experimental signature.

Figure 5.

The (L + R)/2c ratios as computed for the simulations of Fig. 4, against the elevation h. The fine dotted line represents a spline interpolation used as a calibration curve to estimate particle elevations h from the (L + R)/2c ratios of experimental signatures S.

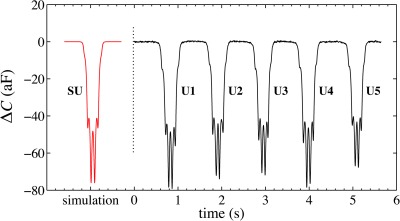

As an illustration of the calibration procedure, consider a set of five randomly chosen experimentally obtained signatures (U1-U5) generated by diameter PSS passing over the electrodes, as represented in Fig. 6.

Figure 6.

Five unactuated signals, U1-U5, are highly symmetric, indicating that there is very little change in elevation as any corresponding PSS flows over the electrode region. The profile of the simulated signal, SU, closely resembles the experimental signatures.

These particles were not actuated by low-frequency DEP forces to ensure their level trajectories. As noted in Ref. 34, over 90% of the particles are expected to flow at a roughly constant elevation between 3 and . We ensured that the path length prior to the electrode region is long enough for the particles to sediment into equilibrium positions, determined by . Video evidence was recorded simultaneously and used to verify that particle flow was also maintained inside the middle third of the channel width, to exclude edge effects.

For these experimental signatures, the amplitude ratios, profile asymmetry, and estimated elevations (using Fig. 5) are summarized in Table TABLE I.. Note that all signals are similar in size, as would be expected for a uniformly sized population of particles. Again, larger amplitudes can emerge from slightly larger particles or from particles at lower elevations. The elevations estimated from the ratios (L + R)/2c indicate that all five spheres passed between 5.7 and above the electrode array, with an average elevation of , consistent with previous observations. Note also that the fraction difference for the two central peaks, 2(L – R)/(L + R) indicates that the peak amplitudes are always within five percent of each other. The expected signal (SU) is obtained by calculating (simulating) the induced capacitance change of a polystyrene sphere flowing horizontally at its equilibrium elevation. The simulation parameters are as follows: particle radius , flow velocity , and equilibrium height .

TABLE I.

Ratio of peaks to central minimum for unactuated particles.

| Signal | Ratio L/c | Ratio R/c | Ratio (L + R)/2 c | 2(L– R)/(L + R) | Estimated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U1 | 1.625 | 1.641 | 1.633 | –0.010 | 5.8 |

| U2 | 1.631 | 1.671 | 1.651 | –0.024 | 5.7 |

| U3 | 1.581 | 1.606 | 1.593 | –0.016 | 6.1 |

| U4 | 1.685 | 1.641 | 1.663 | 0.027 | 5.7 |

| U5 | 1.552 | 1.571 | 1.562 | –0.012 | 6.2 |

CAPACITANCE SIGNATURES OF ACTUATED PARTICLES

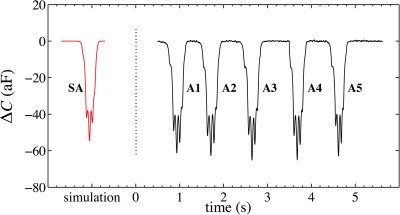

When particles are actuated by repulsive DEP forces, their corresponding capacitance signatures are asymmetric in both amplitude and time. Specifically, DEP repulsion progressively decreases the induced capacitance changes of flowing particles as they are repelled to increasing elevations above the electrodes (Fig. 7). At the same time, the particles experience acceleration as evidenced by the progressively narrower peaks and shorter time intervals between peaks. This velocity increase occurs because the repulsive DEP force directs particles from a relatively low equilibrium elevation () toward the mid-channel (h = H/2) elevation where the fluid velocity is a maximum. Within the lower half of the channel, the particle progressively translates into fluid layers of increasing velocity (cf. Eq. 10).

Figure 7.

Capacitance signatures from five PSS actuated by low-frequency () DEP signal. As the spheres flow above the electrodes, they are repelled into layers of faster fluid flow and subsequently accelerate. The repulsive character of the overall force is evident in the diminishing amplitudes of the signature peaks. The simulated PSS signature (SA) resembles the experimentally obtained signatures.

Actuated particles generate more complex capacitance signatures compared with those of unactuated particles. Specifically, the actuated signatures relate to acceleration, in addition to the cell size, velocity, and position information contained in unactuated signatures. Recall that an actuated particle experiences forces that change rapidly from one location to another (Fig. 3). Consequently, the particle is subject to non-uniform forces, which elevate the particle at variable rates as the particle passes through the analysis volume. This will be evident from a simulated particle trajectory described later (Sec. 7B).

As a consequence, amplitude ratios cannot be used to estimate the elevation of an actuated particle as they would be for unactuated particles. Although impractical, one way to achieve this would be comparing an experimental signal with a different simulation curve at every point along the particle trajectory. Fortunately, a fractional difference in peak amplitudes (for example, 2(R – L)/(L + R), or ), referred to as the “force index” (FI), can provide a useful measure of the average intensity (average acceleration) with which the particle is repelled away from the electrodes. This will be discussed in Sec. 8.

PARTICLE TRAJECTORY SIMULATION

Establishing the initial conditions

To this point, we have described the capacitance signatures induced by unactuated and DEP-actuated particles. As capacitance signatures emerge from unique trajectories, we begin this section by describing how to establish the initial velocity and equilibrium height of a particle in order to calculate its trajectory.

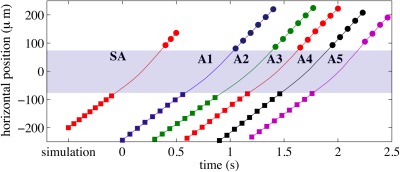

The initial elevation is estimated using the calibration procedure outlined earlier in Sec. 4, and the initial velocity is estimated using video microscopy. Videos captured the horizontal positions of particles U1-U5 and A1-A5 (see Figs. 67 for their capacitance signatures) at a rate of 15 frames per second (fps). Then, using video tracking software (open source ImageJ44 plugin MTrackJ45, 46), we collected the center of mass of each particle at all points along each trajectory. Knowing the time interval between points, the particle velocities can be analyzed.

Only points outside of the acceleration region, that is, points with , were used to estimate the incoming and outgoing horizontal particle velocities. Apparent weight and hydrodynamic lift are balanced before the PSS enters the analysis volume, guaranteeing a constant incoming velocity. After exiting the analysis volume, the PSS is again subject only to apparent weight and lift forces, but is now at a higher elevation. Although close in magnitude, the two forces are not exactly balanced anymore, and the PSS will gradually sink to layers of slower fluid flow. This sinking, however, is slow enough so that the horizontal velocity of the PSS can still be very accurately determined using video tracking.

As expected, tracking of the unactuated particles (U1-U5) resulted in measurements of constant velocity throughout each trajectory. The average incoming velocity of particles U1-U5, was used in the unactuated signal simulation (SU) shown in Fig. 6.

Tracking of the actuated particles (A1-A5) resulted in the velocities , as shown in Fig. 8, and listed in Table TABLE II.. The average incoming velocity of the actuated particles was found to be . This value is slower than the average obtained for the unactuated set of PSS and indicates that the overall flow had slowed during measurements. This also means that the incoming equilibrium elevation has adjusted to a new (slightly lower) elevation.

Figure 8.

Velocities of the actuated PSS are estimated from the center of mass positions obtained by tracking. Both before and after the actuation, PSS move with constant horizontal velocity. (After actuation, PSS slowly sinks back to the equilibrium elevation, but this sinking is slow enough that the horizontal velocity appears very nearly constant during tracking.) Therefore, only points outside of the interval (shown as a shaded strip) were used to estimate the velocities.

TABLE II.

Velocities of actuated particles.

| Signal | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 290 | 263 | 284 | 298 | 274 | |

| 399 | 395 | 397 | 411 | 412 |

The new equilibrium elevation may be calculated by first rearranging Eq. 10 for the mean flow velocity, and then substituting into Eq. 11 to obtain a cubic equation for h

| (13) |

with

| (14) |

For our velocity, the real solution of Eq. 13 is . Thus, an elevation of and a horizontal velocity of were used as initial conditions to simulate the actuated signal, SA, shown in Fig. 7. (Note that the same initial values were used in calculating the horizontal and vertical components of the DEP force shown in Fig. 3.)

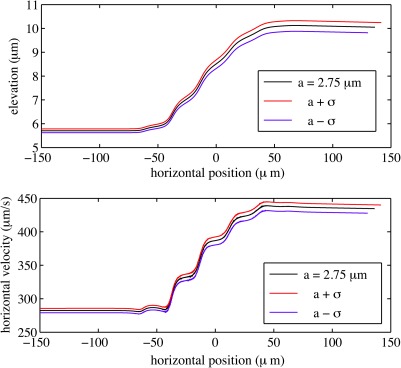

Plotting the trajectory

Using the initial elevation and velocity of the particle, we can now solve the equation of motion to simulate the actuated trajectory. The results of this simulation are summarized in Fig. 9. The trajectories and corresponding velocity variations are calculated for a PSS having a mean radius, as well as for radii that are one standard deviation smaller and larger. Careful inspection of these plots shows that the initial elevation and velocities were appropriately adjusted for particle size: slightly higher and faster for the larger, and slightly lower and slower for the smaller PSS. On average, the repulsive DEP force generated by a DEP rms voltage increases the PSS elevation by about . Since the DEP force is proportional to the volume of the PSS, subtle variations in initial elevation from one particle size to another become amplified in their final elevations.

Figure 9.

Trajectories and velocities for actuated PSS of different radii, as obtained from simulations. Each plot corresponds to an average PSS with radius , as well as for radii that are one standard deviation, , smaller and larger. The DEP force is proportional to the particle size, and a difference of about 3% in radius translates into a 9% change in force—note how slight initial differences in the PSS trajectories become amplified after the actuation.

Note that the trajectory simulation predicts that the velocity would increase from to for a PSS with —a plausible result that compares well with the incoming and outgoing velocities of the actuated signals A1-A5 (listed in Table TABLE II.), which the simulated signal resembles.

DISCUSSION AND RESULTS – YEAST EXAMPLE

To apply the technique for probing dielectric properties of particles described here to a biological sample, we used Brewer’s yeast cells (S. cerevisiae), prepared according to the following procedure: a spoonful () of granulated yeast was initially incubated for 24 h in 100 ml of yeast peptone dextrose (YPD) broth (10 g/l yeast extract, 20 g/l peptone, and 20 g/l dextrose) at . This solution was then progressively diluted to a concentration ten thousand times smaller and used to plate the culture. To this end, of the diluted solution was mixed with of sterile DI water and spread on YPD agar plates (YPD broth agar). Several plates prepared in this way were left in the incubator at for 48 h. After this time, one of the plates with robust growth was selected and one of the colonies was harvested from it, reseeded in a 100 ml of YPD broth and left in the incubator for another 24 h. Starter broth obtained in this way yielded a healthy homogeneous population from which samples were taken for measurements.

On the day of the experiment, the cells were triple washed by centrifuging at 6000 g for 5 min and resuspending in distilled and DI water each time. After the final wash, cells were suspended in DI water to which a solution of methylene blue dye was added to create a suspension with and a measured conductivity of . Methylene blue dye is commonly used to visually test yeast cell viability. The dye penetrates all cells, but only the viable ones metabolize the dye and remain clear, while the non-viable cells are stained blue.47 This labelling affords visual confirmation of cell viability as predicted from the electronic signature S.

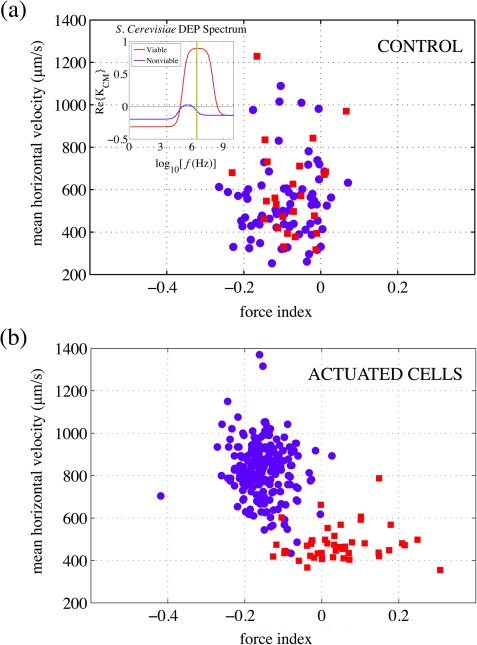

Yeast cells were then pumped through the microfluidic channel and subjected to a DEP potential with amplitude applied at 3 MHz. In addition to the electronic signatures, videos were collected to provide a visual record of the individual cell viability. From the estimates of the Clausius-Mossotti factor () for this frequency region (see the inset in Fig. 10a), DEP potential with amplitude applied at 3 MHz is expected to cause a strong attractive (pDEP) force on the viable cells and a weak repulsive (nDEP) force on the non-viable ones. Experimental results for both the control set (no DEP applied) and the actuated set are represented in Fig. 10.

Figure 10.

Cultured yeast cells were suspended in DI water, with methylene blue dye staining non-viable cells; viable cells remained clear. At 3 MHz, estimates for the (inset in (a)) predict strong pDEP for the viable cells (red squares) and weak nDEP for the non-viable cells (blue circles). (a) In a control set (no DEP applied), all cells flowed with comparable horizontal velocities and indistinguishable force index. (b) With 3 MHz DEP signal applied, data points segregate into two distinct groups, indicating that viable cells are attracted to the electrodes and decelerate as they enter slower layers of fluid, and non-viable cells are repelled from the electrodes and accelerate as they enter faster layers of fluid.

Plotted on the horizontal axis is the DEP force index, chosen to be zero if there is no actuation, positive under pDEP and negative under nDEP. The “average velocity” for each passing yeast cell is calculated by dividing , the distance between the middle points of the two electrode gaps ((l + L)/2 and (R + r)/2), with the average time required for the cell to cover that distance, where s denote the times at which the corresponding peak amplitudes were recorded. It is clear that, when there is no DEP actuation (Fig. 10a), the majority of cells travel at relatively low velocities of , with DEP force index just slightly below zero. Conversely, when the 3 MHz DEP signal is applied (Fig. 10b), the data points segregate into two distinct and separate groups: viable cells (red) are attracted to the electrodes and, therefore, slow down, while the non-viable cells (blue) are repelled and speed up as they transfer into fluid layers with higher velocities.

Separating viable from non-viable yeast cells is not a new achievement: a great number of studies (many of them described in Refs. 5, 6) use DEP actuation to sort and trap biological cells based on their response to the electric field. At the end of this process, cells are often subjected to further analysis and categorization by methods other than DEP—work by Cheng etal.,22 for example, uses Raman spectroscopy to successfully characterize different populations of bacteria. Our device differentiates between cells without necessarily physically separating them (although this could be made possible by addition of traps and channel modifications), but with the aim of utilizing cell responses to the electric field at different frequencies in a way that can achieve a completely electronic characterization. Applications following from this kind of approach would exploit the ability to miniaturize and automate the analysis, ushering in a variety of low-cost sensors of relevance in research and industry alike.

CONCLUSIONS

We devised an all-electronic, label-free technique for simultaneous capacitive detection and DEP actuation of biological cells. The simple example presented in Sec. 8 illustrates the power and applicability of the technique. Using a single electrode array and the equipment that can be readily miniaturized allows us to successfully identify the subpopulations of cells based exclusively on their electronic signature. (Although methylene blue dye was added to the suspension to visually confirm cell viability, this visual input is not a requisite for individual cell identification, as the electronic signatures of the actuated cells contain adequate information.) Furthermore, these electronic signatures are easy to analyse and thus provide the opportunity for full automation. In order to show signatures with good resolution and provide a proper comparison with simulations, we restricted flows to slow speeds: , which (with dilution of about particles—or cells—per milliliter) translates into a throughput of about 3 or 4 particles per second. Nothing prevents us, however, from increasing this throughput to 10- or even 100-fold in the future.

As a next step in developing this technique, it could be used to discriminate between subpopulations of cells that differ much more subtly in their ionic composition than viable and non-viable yeast do. The ability to identify, for example, cells in different metabolic states would facilitate the design of various online and offline probes and detectors. The ability to miniaturize and completely automate the analysis opens up a possibility for a low-cost alternative biosensor with applications in biomedical research and healthcare.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Jessica Saunders and Dr. Paveen Sharma of the Biosystems lab at the Engineering Department of University of Manitoba for their assistance with the preparation of yeast culture. This work was funded in part by the Blewett Scholarship (M.N.-J.) awarded through the American Physical Society (APS). The authors would also like to thank: the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC); the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI); the Province of Manitoba; Western Economic Diversification Canada (WD); and Canadian Microelectronics Corporation (CMC) Microsystems for financial support of this research.

References

- Pantel K. and Brackenhoff R. H., Nature Rev. 4, 448 (2004). 10.1038/nrc1370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suresh S., Spatz J., Mills J. P., Micoulet A., Dao M., Lim C. T., Beil M., and Seufferlein T., Acta Biomater. 1, 15 (2005). 10.1016/j.actbio.2004.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohl H. A., J. Appl. Phys. 22, 869 (1951). 10.1063/1.1700065 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pohl H. A., Dielectrophoresis: The Behaviour of Neutral Matter in Nonuniform Electric Fields (Cambridge University Press, 1978). [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon Z., Electrophoresis 32, 2466 (2011). 10.1002/elps.201100060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pethig R., Biomicrofluidics 4, 022811 (2010). 10.1063/1.3456626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toner M. and Irimia D., Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 7, 77 (2005). 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.7.011205.135108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S. K., Daggolu P. R., Burgess S. C., and Minerick A. R., Electrophoresis 29, 5033 (2008). 10.1002/elps.200800166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczenski R. S., Chang H.-C., and Revzin A., Biomicrofluidics 5, 032005 (2011). 10.1063/1.3608135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gascoyne P., Mahidol C., Ruchirawat M., Satayavivad J., Watcharasitb P., and Becker F. F., Lab Chip 2, 70 (2002). 10.1039/b110990c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F., Yang X., Jiang H., Bulkhaults P., Wood P., Hrushesky W., and Wang G., Biomicrofluidics 4, 013204 (2010). 10.1063/1.3279786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker F. F., Wang X.-B., Huang Y., Pethig R., Vykoukal J., and Gascoyne P. R. C., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 92, 860 (1995). 10.1073/pnas.92.3.860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gascoyne P. R. C., Wang X.-B., Huang Y., and Becker F. F., IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 33, 670 (1997). 10.1109/28.585856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley H. M., Labeed F. H., Thomas H., and Hughes M. P., Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1770, 601 (2007). 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labeed F. H., Coley H. M., and Hughes M. P., Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1760, 922 (2006). 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Holzel R., Pethig R., and Wang X.-B., Phys. Med. Biol. 37, 1499 (1992). 10.1088/0031-9155/37/7/003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demierre N., Braschler T., Muller R., and Renaud P., Sens. Actuators B 132, 388 (2008). 10.1016/j.snb.2007.09.078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan L. A., Lu J., Wang L., Marchenko S., Jeon N. L., Lee A. P., and Monuki E. S., Stem Cells 26, 656 (2008). 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vykoukal J., Vykoukal D. M., Freyberg S., Alt E. U., and Gascoyne P. R., Lab Chip 8, 1386 (2008). 10.1039/b717043b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht D. R., Underhill G. H., Wassermann T. B., Sah R. L., and Bhatia S. N., Nat. Methods 3, 369 (2006). 10.1038/nmeth873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pysher M. D. and Hayes M. A., Anal. Chem. 79, 4552 (2007). 10.1021/ac070534j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng I.-F., Chang H.-C., Hou D., and Chang H.-C., Biomicrofluidics 1, 021503 (2007). 10.1063/1.2723669 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim U., Qian J., Kenrick S. A., Daugherty P. S., and Soh H. T., Anal. Chem. 80, 8656 (2008). 10.1021/ac8015938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellarnau M., Errachid A., Madrid C., Juárez A., and Samitier J., Biophys. J. 91, 3937 (2006). 10.1529/biophysj.106.088534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaler K. and Pohl H. A., IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. IA-19, 1089 (1983). 10.1109/TIA.1983.4504339 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaler K. V. I. S. and Jones T. B., Biophys. J. 57, 173 (1990). 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82520-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei M.-T., Junio J., and Ou-Yang H. D., Biomicrofluidics 3, 012003 (2009). 10.1063/1.3058569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes D. and Morgan H., Anal. Chem. 82, 1455 (2010). 10.1021/ac902568p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stott S. L., Hsu C.-H., Tsurkov D. I., Yu M., Miyamoto D. T., Waltman B. A., Rothenberg S. M., Shah A. M., Smas M. E., Korir G. K., Floyd F. P., Gilman A. J., Lord J. B., Winokur D., Springer S., Irimia D., Nagrath S., Sequist L. V., Lee R. J., Isselbacher K. J., Maheswaran S., Haber D. A., and Toner M., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 18392 (2010). 10.1073/pnas.1012539107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gascoyne P. R. and Vykoukal J., Electrophoresis 23, 1973 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voldman J., Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 8, 425 (2006). 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.8.061505.095739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau L. and Lifshitz E., Electrodynamics of Continuous Media, 2nd ed. (Pergamon, 1984). [Google Scholar]

- Jones T. B., Electromechanics of Particles (Cambridge University Press, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- Nikolic-Jaric M., Romanuik S. F., Ferrier G. A., Bridges G. E., Butler M., Sunley K., Thomson D. J., and Freeman M. R., Biomicrofluidics 3, 034103 (2009). 10.1063/1.3187149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markx G. H. and Davey C. L., Enzyme Microb. Technol. 25, 161 (1999). 10.1016/S0141-0229(99)00008-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Gupta M. C., Dudley K. L., and Lawrence R. W., Nanotechnology 15, 1545 (2004). 10.1088/0957-4484/15/11/030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasubramaniam R., Chen J., and Liu H., Appl. Phys. Lett. 83, 2928 (2003). 10.1063/1.1616976 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Honegger T., Berton K., Picard E., and Peyrade D., Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 181906 (2011). 10.1063/1.3583441 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M. P., Morgan H., and Flynn M. F., J. Colloid Interface Sci. 220, 454 (1999). 10.1006/jcis.1999.6542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold W. M., Schwan H. P., and Zimmermann U., J. Phys. Chem. 91, 5093 (1987). 10.1021/j100303a043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrier G. A., Romanuik S. F., Thomson D. J., Bridges G. E., and Freeman M. R., Lab Chip 9, 3406 (2009). 10.1039/b908974h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams P. S., Koch T., and Giddings J. C., Chem. Eng. Comm. 111, 121 (1992). 10.1080/00986449208935984 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Wang X.-B., Becker F. F., and Gascoyne P. R. C., Biophys. J. 73, 1118 (1997). 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78144-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/ for the ImageJ, public domain Java-based image processing program.

- Meijering E., http://www.imagescience.org/meijering/software/mtrackj/ (2012).

- Meijering E., Dzyubachyk O., and Smal I., Imaging and Spectroscopic Analysis of Living Cells (Elsevier, 2012), pp. 183–200. [Google Scholar]

- Glick B. R. and Pasternak J. J., Molecular Biotechnology: Principles and Applications of Recombinant DNA, 4th ed. (American Society of Microbiology, 2010). [Google Scholar]