Abstract

Background

Gabapentin reduces acute postoperative and chronic neuropathic pain, but its sites and mechanisms of action are unclear. Based on previous electrophysiologic studies, we tested whether gabapentin reduced γ-Amino butyric acid (GABA) release in the locus coeruleus (LC), a major site of descending inhibition, rather than in the spinal cord.

Methods

Male Sprague-Dawley rats with or without L5-L6 spinal nerve ligation (SNL) were used. Immunostaining for glutamic acid decarboxylase and GABA release in synaptosomes and microdialysates were examined in the LC and spinal dorsal horn.

Results

Basal GABA release and expression of glutamic acid decarboxylase increased in the LC but decreased in the spinal dorsal horn following SNL. In microdialysates from the LC, intravenously administered gabapentin decreased extracellular GABA concentration in normal and SNL rats. In synaptosomes prepared from the LC, gabapentin and other α2δ ligands inhibited KCl-evoked GABA release in normal and SNL rats. In microdialysates from the spinal dorsal horn, intravenous gabapentin did not alter GABA concentrations in normal rats but slightly increased them in SNL rats. In synaptosomes from the spinal dorsal horn, neither gabapentin nor other α2δ ligands affected KCl-evoked GABA release in normal and SNL rats.

Discussion

These results suggest that peripheral nerve injury induces plasticity of GABAergic neurons differently in the LC and spinal dorsal horn, and that gabapentin reduces pre-synaptic GABA release in the LC but spinal dorsal horn. The present study supports the idea that gabapentin activates descending noradrenergic inhibition via disinhibition of LC neurons.

Introduction

Gabapentin produces analgesia in a wide range of animal pain models1–5 and in patients with acute post-operative pain and chronic neuropathic pain.6, 7 Despite this widespread use, the sites and mechanisms of analgesic action of gabapentin remain uncertain. Gabapentin binds with high affinity to the α2δ subunits of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels,8 and this molecular site is important to gabapentin induced analgesia.9–11 Although acute inhibition of Ca2+ currents by gabapentin is either very minor or absent,12 gabapentin inhibits trafficking of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels to the cell membrane by binding to α2δ subunits13–15 which are upregulated in primary sensory afferents and the spinal cord in rats after peripheral nerve injury.11 Despite demonstration of α2δ subunits as molecular targets of gabapentin action, the identity and neuronal circuits essential to gabapentin analgesia remain obscure.

Since spinal plasticity and sensitization play pivotal roles in neuropathic pain following peripheral nerve injury, most laboratory studies have focused on actions of gabapentin in the spinal cord, where it reduces afferent traffic and responses of spinal projection neurons.4, 10, 11, 16, 17 However, it is unlikely that gabapentin relies exclusively on spinal actions for analgesia. We and others have demonstrated in rodents after paw incision and peripheral nerve injury and in humans with chronic pain that systemically administered gabapentin activates descending bulbospinal noradrenergic inhibition to produces analgesia, blocked by intrathecal α2-adrenoceptor antagonists.2, 3, 5 Additionally, gabapentin, both systemically administered in vivo and locally applied to isolated brainstem slices, activates noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus (LC).18 These results suggest that gabapentin acts on the local circuits within the brainstem to activate descending noradrenergic inhibition.

γ-Amino butyric acid (GABA), the prototypical inhibitory neurotransmitter of the central nervous system, plays an important role in sensory processing, and analgesic effects of gabapentin may reflect modulation of GABA release. Gabapentin’s actions on GABA release are controversial and likely depend on the site in the central nervous system. For example, some studies show an increase in extracellular concentration of GABA in the brain from gabapentin,19–21 whereas others show a direct reduction in GABA release when cortical synaptosomes are exposed to gabapentin.22 In the LC, gabapentin reduces GABA-mediated inhibitory post-synaptic currents and thereby dis-inhibits LC neurons,23 consistent with the activation of LC neurons by gabapentin.18 The effect of gabapentin on spinal GABA release in normal and neuropathic states has not been fully examined.

The present study tested whether gabapentin and other α2δ ligands inhibit GABA release in the LC and spinal cord, using intact (in vivo microdialysis) and isolated (in vitro synaptosomes) approaches to examine circuit and direct effects, respectively, in normal and neuropathic rats. We further tested whether peripheral nerve injury regulates extracellular GABA concentration and expression of the GABA-synthesizing enzyme glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) in the LC and spinal cord.

Materials and Methods

Animals and surgeries

Male Sprague-Dawley rats, weighing 180–250 g, from Harlan Industries, housed under a 12-h light-dark cycle with food and water ad libitum, were used. All experiments were approved by Animal Care and Use Committee at Wake Forest University (Winston Salem, NC). L5-L6 spinal nerve ligation (SNL) was performed as previously described.24 Briefly, under anesthesia with 2% isoflurane in oxygen, the right L6 transverse process was removed and the right L5 and L6 spinal nerves were tightly ligated using 5–0 silk suture. Seven to ten days after SNL, some animals were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane and placed securely in a stereotaxic frame. A sterile steel guide cannula (CXG-8, EICOM CO., Kyoto, Japan) was implanted into the right LC as previously described.18 The coordinates for placement of the tip of the guide cannula were 9.8 mm posterior and 1.4 mm lateral to the bregma, and 6.5 mm ventral from the surface of the dura mater, according to the rat brain atlas.25 Animals were allowed to recover for at least 5 days prior to the study.

Timing and rationale of experimental manipulations

The primary purpose of the current study was to probe the effect and mechanisms of action of gabapentin on GABA release in the LC. We therefore examined more concentrations of gabapentin as well as testing whether other drugs acting on α2δ subunits (L-isoleucine, pregabalin) in this preparation than in the spinal cord.

Microdialysis for GABA measurement

On the day of experiment, anesthesia was induced with 2% isoflurane and then maintained with 1.25–1.5% isoflurane during the study. A heating blanket was used to maintain rectal temperature 36.5 ± 0.5°C and the right jugular vein was cannulated for saline infusion (1.2 ml/kg/hr) and gabapentin (Toronto Research Chemicals Inc., North York, Toronto, Canada) or pregabalin (gift from Pfizer Inc., New York, NY) injection. For microdialysis in the spinal dorsal horn, the L3–L6 level of spinal cord was exposed by the T13-L1 laminectomy. A microdialysis probe (OD = 0.22 mm, ID = 0.20 mm, length = 1 mm, CX-I-8-01, EICOM CO.) was inserted from just lateral to the right dorsal root 1 hr prior to the study and perfused with Ringer’s solution (1.0 µL/min). Fractions were collected every 30 min for 2.5 hr starting 1 hr prior to drug treatment and samples were kept at −80 °C until assayed for GABA. For microdialysis in the LC, a probe was inserted through the guide cannula and microdialysis was performed using the same protocol as described for the spinal cord. After the experiment, the probe was perfused for 10 min with methylene blue to stain the areas surrounding the active dialysate window in the brainstem. Rats were then killed by decapitation, and the brainstem was removed and post-fixed with 8% buffered paraformaldehyde overnight. After sectioning, the placement of the probe was verified microscopically. Data were used only from animals with staining in the LC. GABA content in the microdialysates was measured by a high pressure liquid chromatography system with electrochemical detection (HTEC-500, EICOM CO.). GABA in samples were derivatized with 2-mercaptoethanol and ο-phthaldialdehyde (4 mM) in 0.1 M carbonate buffer (pH=9.5). The ο-phthaldialdehyde derivatives were then separated on the column (3.0 mm × 150 mm, SC-5ODS, EICOM CO) at 30°C, using a mobile phase consisting of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH=2.8) and methanol (1:1 vol/vol) containing 5 mg/ml EDTA-2Na at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The limit of detection of GABA assay in the current study was 1.5 pg per injection.

GABA release from Synaptosomes

Under deep anesthesia with 5% isoflurane, animals were killed by decapitation and the brainstem and spinal lumbar enlargement were quickly removed and placed in ice-cold sucrose (0.32 M)-HEPES (10 mM) buffer, pH = 7.4. Brainstem slices (2 mm thickness) containing the LC were obtained using a precision brain slicer (RBM-4000C, ASI Instruments, Inc., Warren, MI), the region of the LC was carefully dissected under the surgical microscope, and homogenized in ice-cold sucrose-HEPES buffer. Each brainstem synaptosome preparation contained the bilateral LC and adjacent tissue from 4 normal or 4 SNL rats. Since SNL surgery or gabapentin equally activates the LC bilaterally,18 we used bilateral LCs for the present study. The lumbar spinal dorsal horn tissue ipsilateral to SNL surgery was obtained from 4 SNL rats for each synaptosome preparation, as previously described.26 Control spinal cord tissue was obtained bilaterally from 2 normal rats. The initial homogenate was centrifuged at 1,000×G for 3 min and the resulting supernatant was centrifuged again at 10,000×G for 13 min. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was resuspended in Krebs buffer (in mM: NaCl 124, KCl 3, MgSO4 2, CaCl2 2, NaH2PO4 1.25, NaHCO3 25, and glucose 10, saturated with 95% O2-5% CO2, pH = 7.4). [3H]-GABA release from synaptosomes was measured as previously described,22 with minor modifications. After incubation with [3H]-GABA and unlabeled GABA (final concentration of 0.25 µCi/ml and 1 µM, respectively) for 20 min at 37°C, the synaptosome-containing solution was centrifuged at 10,000×G for 5 min and the pellet was resuspended in Krebs buffer. Each synaptosome preparation was divided into six equal aliquots and transferred to Whatman filters in temperature controlled perfusion chambers (SF-12, Brandel, Gaithersburg, MD). Synaptosomes were perfused with Krebs buffer (0.8 ml/min) for 25 min to remove free radioactivity, and then fractions were collected every 5 min for 20 min. After a 10 min baseline collection, synaptosomes were perfused with a test drug, either gabapentin, pregabalin, L-isoleucine (Sigma Chemical CO, St. Louis, MO), or D-isoleucine (Sigma Chemical CO), for 2 min and then stimulated with 25 mM KCl-Krebs buffer (in mM: NaCl 102, KCl 25, MgSO4 2, CaCl2 2, NaH2PO4 1.25, NaHCO3 25, and glucose 10, pH = 7.4) containing a test drug for 3 min. The inhibitor of GABA transporters 1,2,5,6-tetrahydro-1-[2-[[(diphenylmethylene)amino]oxy]ethyl]-3-p yridinecarboxylic acid hydrochloride (NNC-711, 1 µM, Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO) was present during perfusion to inhibit reuptake of GABA.22 Amount of radioactivity of each fraction was measured by a liquid scintillation spectrometry (LS6500, Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA).

Immunohistochemistry

Under deep anesthesia with intraperitoneal pentobarbital (100 mg/kg), animals were perfused intracardially with cold phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) containing 1% sodium nitrite followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline. The spinal cord and brainstem from normal and SNL rats were postfixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 3 h, cryoprotected with 30% sucrose for 48 h at 4°C, and sectioned on a cryostat at a 16-µm thickness. For staining in the spinal cord, after pretreatments with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide, 50% ethanol, and 1.5% normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA), the sections were incubated with a mouse anti-GAD67 antibody (1:1000; Millipore, Billerica, MA) in 1.5% normal donkey serum for 24 h at 4°C. The sections were then incubated with biotinylated donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc.), processed using an Elite Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and developed by the standard glucose oxidase-nickel method. For staining in the LC, the sections were incubated with a rabbit anti-tyrosine hydroxylase antibody (1:500; Pel-Freez Biologicals, Rogers, AR) and a mouse anti-GAD67 antibody (1:500) followed by a Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:600; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc.), a biotinylated donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:200), and Cy2-conjugated strepavidian (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc.).

For quantification of GAD67 immunoreactivity, 4–5 brainstem and spinal cord sections were randomly selected from each rat. Images of dorsal horns and LCs from normal or SNL rats were captured using a digital charged couple device camera. The area of the LC was identified by a cluster of tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactive cells. By using an image analysis software (SigmaScan Systat Software, San Jose, CA), pixels of GAD67-immunoreactive objects within the area of the dorsal horn containing lamina I-IV or the LC were quantified based on a constant threshold of optical density. Data are expressed as a percentage of GAD67-immunoreactive pixels in total pixels of the quantified area. The person performing image analysis was blinded to treatment.

Statistical Analyses

Otherwise stated, data are presented as mean ± SE. Differences among groups for microdialysis experiments were determined using two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) and other data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Basal GABA release and GAD immunoreactivity in the LC and spinal dorsal horn

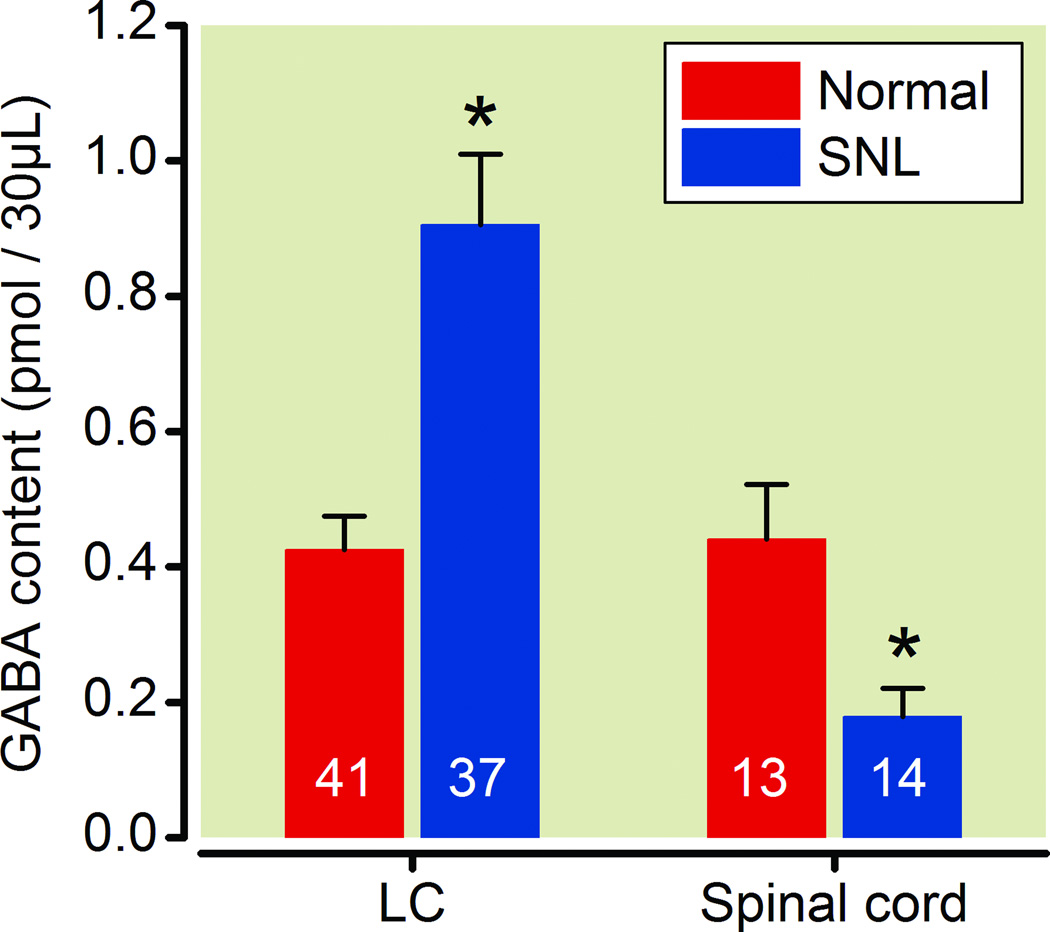

In microdialysates from the LC, basal GABA concentrations were significantly greater from SNL compared to normal rats (Fig.1). The opposite effect of SNL was observed in the spinal cord, where, basal GABA concentrations in microdialysates were significantly less from SNL compared to normal rats.

Fig. 1.

SNL altered basal γ-Amino butyric acid (GABA) release from the locus coeruleus (LC) and spinal cord ipsilateral to surgery. Data are presented as GABA content in microdialysates during baseline collection for 30 min. N=13–41. *P<0.05 vs. normal.

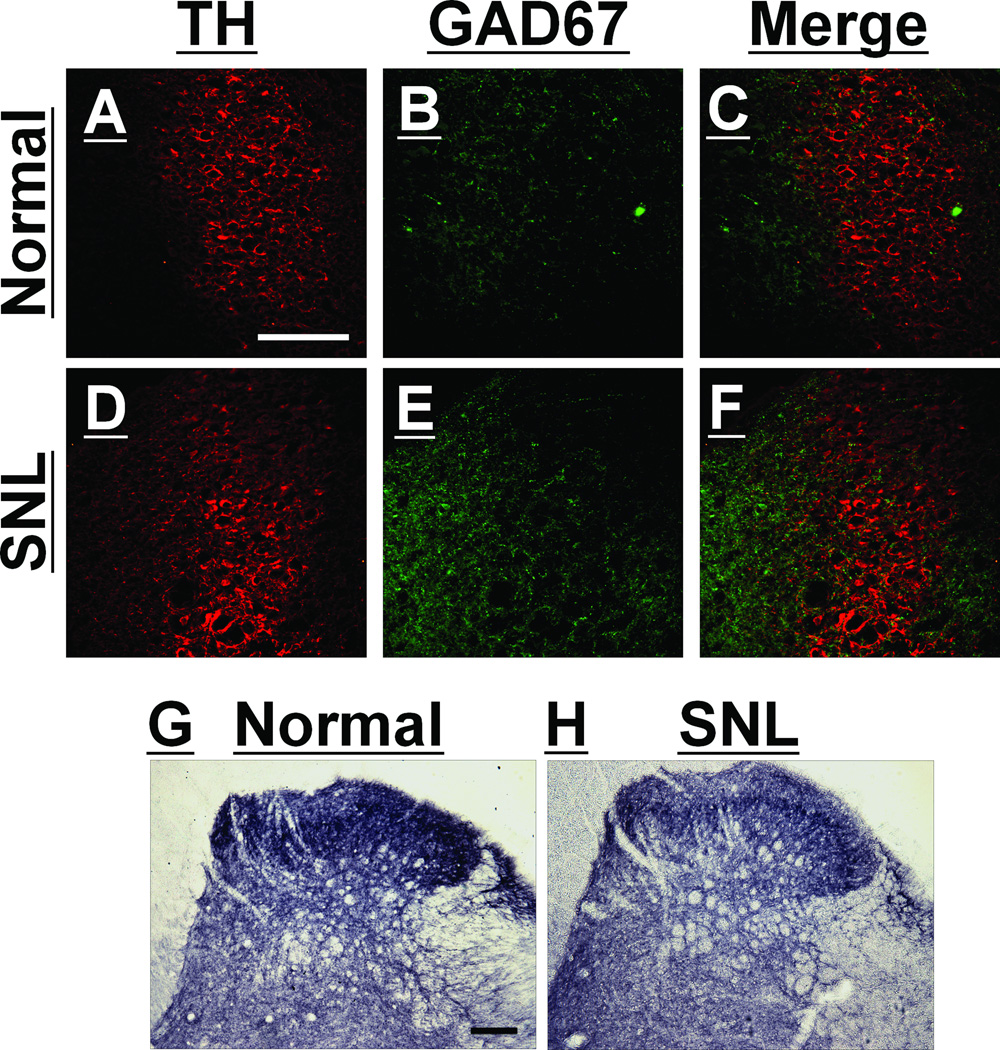

Figure panels 2A-F depict the LC, identified by a cluster of TH-immunoreactive cells, and GAD67-immunoreactivity within and adjacent to the LC in normal and SNL rats. GAD67-immunoreactivity within the LC was found mainly in axons but a few GAD67-positive cells were also found in both normal and SNL rats. Quantitatively, GAD67-immunoreactivity in the LC was significantly great in tissue from SNL compared to normal rats (2.94 ± 0.51% pixels above threshold versus 1.03 ± 0.20%, respectively; n=5 per group; P<0.01). In the lumbar spinal dorsal horn, GAD67-immonoreactivity was found in axons and cells in both normal and SNL rats (Fig. 2G and 2H). As with basal GABA concentrations, the effect of SNL on GAD67-immunoreactivity in the spinal dorsal horn was opposite that observed in LC, with less immunoreactivity in SNL rats compared to normal rats (5.21 ± 0.94% pixels above threshold versus 8.04 ± 0.49%, respectively; n=6 per group; P<0.01).

Fig. 2.

Spinal nerve ligation (SNL) altered glutamic acid decarboxylase 67 (GAD67)-immunoreactivity in the locus coeruleus (LC) and spinal dorsal horn ipsilateral to surgery. A–F: Photomicrographs of immunostaining for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH: A and D), GAD67 (B and E), and their merge (C and F) in the LC of normal (A, B, and C) and SNL (D, E, and F) rats at 2 weeks after surgery. G–H: Photomicrographs of immunostaining for GAD67 in the lumbar spinal dorsal horn of normal (G) and SNL (H) rats. Scale bar = 100 µm.

Microdialysis studies

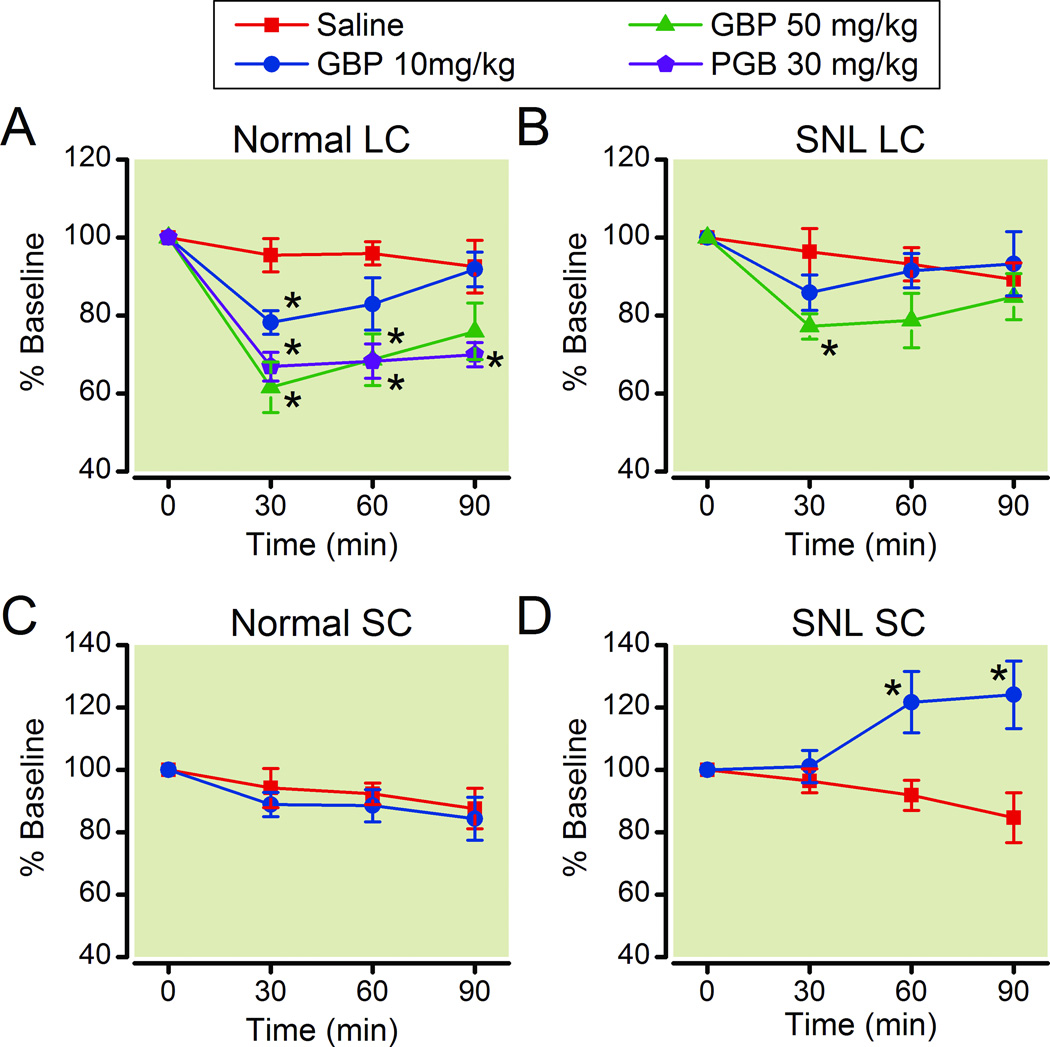

In normal animals, intravenous injection of gabapentin (10 and 50 mg/kg) dose-dependently decreased GABA concentrations in microdialysates from the LC compared to saline (Fig. 3A). Similarly, another gabapentin-related α2δ ligand pregabalin (30 mg/kg) significantly decreased GABA concentrations in microdialysates from the LC compared to saline in normal rats (Fig. 3A). The peak effect of both drugs was observed at 30 min after injection. In SNL rats, only high dose of gabapentin (50 mg/kg) significantly decreased GABA concentrations in microdialysates from the LC compared to saline (Fig. 3B). Although the percentage decreases from the baseline by gabapentin (50 mg/kg) did not differ in normal and SNL rats (p=0.127), the quantitative decrease in GABA concentration in the dialysates collected from 0–30 min after gabapentin injection compared to the baseline was significantly greater in SNL rats (0.18 ± 0.03 pmol/30µl, n=12) than in normal rats (0.10 ± 0.02 pmol/30µl, n=13, p<0.05).

Fig. 3.

Effects of gabapentin and pregabalin on γ-Amino butyric acid (GABA) release in the locus coeruleus (LC) and spinal cord (SC). Normal (A and C) and spinal nerve ligated (SNL: B and D) rats received intravenous saline, gabapentin (GBP 10 and 50 mg/kg), or pregabalin (PGB, 30 mg/kg). Changes in GABA content in microdialysates from the LC (A and B) and spinal cord (C and D) are presented over time as percentage of baseline. N=8–14. *P<0.05 vs. saline.

In the spinal dorsal horn, gabapentin (50 mg/kg) did not affect GABA concentrations in microdialysates compared to saline in normal rats (Fig. 3C). In SNL rats, gabapentin (50 mg/kg) slightly but significantly increased GABA concentrations in microdialysates from the spinal dorsal horn compared to saline (Fig. 3D).

Synaptosome studies

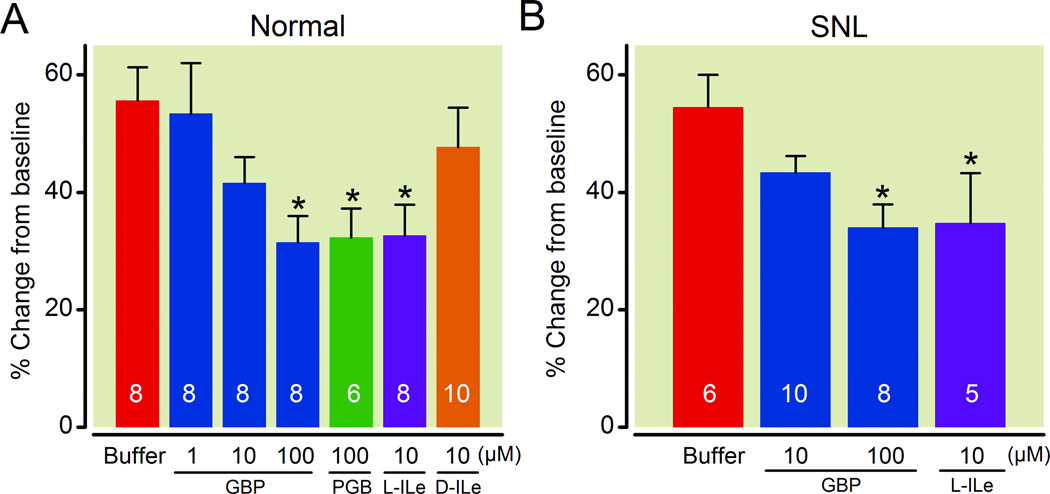

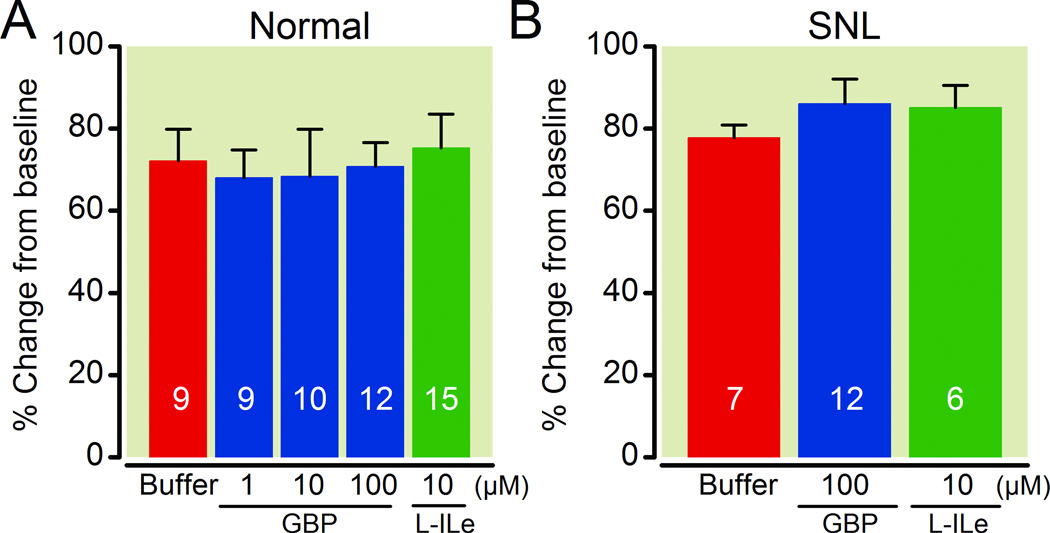

In LC-containing synaptosomes, gabapentin reduced 25 mM KCl-evoked [3H]-GABA release in a concentration-dependent manner in both normal and SNL rats (Fig.4). Pregabalin (100 µM) or an endogenous α2δ subunit ligand L-isoleucine (10 µM) also significantly reduced KCl-evoked [3H]-GABA release from the LC synaptosomes in normal and SNL rats. In contrast, the inactive enantiomer of L-isoleucine, D-isoleucine (10 µM), failed to affect KCl-evoked [3H]-GABA release from the LC synaptosomes in normal rats (Fig.4). As shown in Figure 5, neither gabapentin nor L-isoleucine affected KCl-evoked [3H]-GABA release from the lumbar spinal dorsal horn synaptosomes in either normal or SNL rats.

Fig. 4.

Effects of gabapentin and other α2δ subunit ligands on 25 mM KCl-evoked γ-Amino butyric acid (GABA) release in synaptosomes prepared from the locus coeruleus (LC) and its adjacent tissues. Data are presented as percentage change from baseline release. Synaptosomes from normal (A) and spinal nerve ligated (SNL: B) rats were treated with buffer, gabapentin (GBP, 1–100 µM), pregabalin (PGB, 100 µM), L-isoleucine (L-ILe, 10 µM), or D-isoleucine (D-ILe, 10 µM). N=5–10. *P<0.05 vs. buffer.

Fig. 5.

Effects of gabapentin and L-isoleucine on 25 mM KCl-evoked γ-Amino butyric acid (GABA) release in synaptosomes prepared from the lumbar spinal dorsal horn. Data are presented as percentage change from baseline release. Synaptosomes from normal (A) and spinal nerve ligated (SNL: B) rats were treated with buffer, gabapentin (GBP, 1–100 µM), or L-isoleucine (L-ILe, 10 µM). N=6–15.

Discussion

Despite its name and structural similarity to GABA, gabapentin is thought primarily to act on subunits of Ca2+ channels without direct effects on GABA or its receptors. Additionally, a focus on the spinal cord as a key site of sensory processing and plasticity after nerve injury has led to an assumption, supported by some electrophysiologic experiments, that gabapentin has a primary site of action in the spinal cord. Recently, we and others have challenged this dogma, demonstrating that noradrenergic neurons in the LC are excited by gabapentin, coincident with noradrenaline release in the spinal cord and behavioral anti-hypersensitivity,2, 5, 18 and a GABA-mediated response of gabapentin in the LC has been suggested in electrophysiologic experiments.23 The current study adds importantly to these single cell studies by demonstrating that gabapentin and other α2δ ligands inhibit GABA release in vivo, and that this effect is in part due to direct pre-synaptic inhibition, as demonstrated in vitro using synaptosomes. We confirm that the substrate for this effect of gabapentin is increased after the stress of peripheral nerve injury, confirming previous results with other non-painful stressors. 27, 28 The lack of α2δ ligand action on GABA release in the spinal dorsal horn, suggests that surpraspinal rather than spinal sites of action are important to gabapentin analgesia, at least as it relates to GABA mediated mechanisms.

Basal GABA release and GAD immunoreactivity in the LC increased after nerve injury in the current study, consistent with previous observations of increased GAD expression in the LC under other forms of chronic physical and psychological stress conditions in rats.27, 28 One might therefore expect that increased GABA tone in the LC after peripheral nerve injury would result in reduced activity of noradrenergic neurons and of descending inhibition. Yet, we and others previously demonstrated just the opposite: peripheral nerve injury in rats increases noradrenergic cell activation in the LC, coincident with increased basal release of noradrenaline in the spinal dorsal horn.18 The reasons for this discrepancy are unclear. Other, non-painful chronic stress states increase glutamate content in brain regions 29, 30 and down-regulate the expression of GABAA receptors.31, 32 Should similar effects occur in the LC, it is possible that nerve injury, despite increased basal GABA release, results in a net excitation by increasing glutamate release and reducing postsynaptic GABA receptor expression. We are currently testing this hypothesis.

Although controversial, several studies have observed a reduction of GABA release in the spinal cord after nerve injury, presumably allowing hyper-excitation of spinal neurons and resulting in behavioral hypersensitivity.33. In the current study, basal GABA release and GAD immunoreactivity decreased in the spinal dorsal horn after nerve injury, consistent with previous observations in rats after peripheral nerve or spinal cord injury.34–36

The effect of gabapentin on GABA release varies widely and in different directions depending on brain region.22, 37–39 Here and in other studies, gabapentin and other α2δ ligands decrease pre-synaptic GABA release in the LC,23 consistent with gabapentin-induced activation of noradrenergic neurons in the LC and noradrenaline release in the spinal dorsal horn.18 These results suggest that gabapentin reduces pre-synaptic GABA release to dis-inhibit LC neurons via α2δ interactions both in normal and SNL animals. Interestingly, gabapentin does not affect mechanical withdrawal threshold in normal rats.4, 18 The reasons why increased withdrawal threshold by gabapentin is only seen after SNL, whereas similar effects on GABA release in the LC by gabapentin are observed in normal and SNL rats, are unknown. Perhaps the hypersensitive state of the spinal cord after nerve injury may be required to unmask a significant effect of descending noradrenergic tone. It is also conceivable that increased basal release of noradrenaline and α2-adrenoceptor-mediated acetylcholine release which develop after injury3, 18, 26, 40 are responsible. It should be noted that microdialysis experiments were performed in the presence of isoflurane, which could have reduced the dynamic range of GABA release observed.

In contrast to the LC, both gabapentin and L-isoleucine failed to affect KCl-evoked GABA release from spinal dorsal horn synaptosomes in normal and SNL animals, suggesting that expression or function of α2δ subunits on GABAergic terminals is either very low or absent in the spinal dorsal horn. On the other hand, systemically administered gabapentin induced a small but significant increase in spinal GABA release in SNL rats but not in normal rats. Since systemic administered gabapentin induces more spinal noradrenaline release in SNL rats than normal rats18 and since noradrenaline activates some GABAergic neurons in the spinal dorsal horn via α1-adrenoceptors,41, 42, gabapentin-induced spinal noradrenaline release may contribute to this small increase of spinal GABA release in the presence of nerve injury. The role of this mildly enhanced spinal GABA release for gabapentin analgesia is unclear, since GABAA and GABAB receptor antagonists did not affect analgesia from intrathecally injected gabapentin in SNL rats.43

In summary, peripheral nerve injury induces different GABAergic neuronal plasticity in the LC and spinal dorsal horn, increasing expression and release of GABA in the LC but decreasing it in the spinal cord. Gabapentin and other α2δ ligands inhibit pre-synaptic GABA release in the LC but not in the spinal dorsal horn. These results suggest that gabapentin reduces the influence of GABA in the LC as one mechanism by which it activates descending inhibition from this structure.

MS #201110020 – Final Boxed Summary Statement.

What we already know about this subject:

Gabapentin causes analgesia through binding to α2δ subunits of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels

Gabapentin acts on noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus

Activation of descending noradrenergic inhibition is one mechanism of gabapentin analgesia

What we know from this paper that is new

Gabapentin inhibits presynaptic γ–aminobutyric acid (GABA) release in the locus coeruleus, but not in the spinal dorsal horn

Gabapentin activates descending inhibition from the locus coeruleus, at least in part, by reducing the influence of GABA in the locus coeruleus

Acknowledgements

The authors thank to Dr Helen Baghdoyan (Univeristy of Michigan) for helping to obtain preliminary data of GABA microdialysis.

Funding: This work was supported by grants NS57594 to JE and DA27690 to KH from the National Institute of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Summary Statement: Peripheral nerve injury increases γ-Amino butyric acid content in the locus coeruleus and gabapentin decreases γ-Amino butyric acid release in this structure, but not in the spinal cord.

References

- 1.Chen SR, Pan HL. Effect of systemic and intrathecal gabapentin on allodynia in a new rat model of postherpetic neuralgia. Brain Res. 2005;1042:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayashida K, DeGoes S, Curry R, Eisenach JC. Gabapentin activates spinal noradrenergic activity in rats and humans and reduces hypersensitivity after surgery. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:557–562. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200703000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayashida K, Parker R, Eisenach JC. Oral gabapentin activates spinal cholinergic circuits to reduce hypersensitivity after peripheral nerve injury and interacts synergistically with oral donepezil. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:1213–1219. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000267605.40258.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan HL, Eisenach JC, Chen SR. Gabapentin suppresses ectopic nerve discharges and reverses allodynia in neuropathic rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;288:1026–1030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanabe M, Takasu K, Kasuya N, Shimizu S, Honda M, Ono H. Role of descending noradrenergic system and spinal alpha2-adrenergic receptors in the effects of gabapentin on thermal and mechanical nociception after partial nerve injury in the mouse. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;144:703–714. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laird MA, Gidal BE. Use of gabapentin in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:802–807. doi: 10.1345/aph.19303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahl JB, Mathiesen O, Moiniche S. 'Protective premedication': an option with gabapentin and related drugs? A review of gabapentin and pregabalin in in the treatment of post-operative pain. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2004;48:1130–1136. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2004.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynch JJ, 3rd, Honore P, Anderson DJ, Bunnelle WH, Mortell KH, Zhong C, Wade CL, Zhu CZ, Xu H, Marsh KC, Lee CH, Jarvis MF, Gopalakrishnan M. (L)-Phenylglycine, but not necessarily other alpha2delta subunit voltage-gated calcium channel ligands, attenuates neuropathic pain in rats. Pain. 2006;125:136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gee NS, Brown JP, Dissanayake VU, Offord J, Thurlow R, Woodruff GN. The novel anticonvulsant drug, gabapentin (Neurontin), binds to the alpha2delta subunit of a calcium channel. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5768–5776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li CY, Zhang XL, Matthews EA, Li KW, Kurwa A, Boroujerdi A, Gross J, Gold MS, Dickenson AH, Feng G, Luo ZD. Calcium channel alpha2delta1 subunit mediates spinal hyperexcitability in pain modulation. Pain. 2006;125:20–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luo ZD, Calcutt NA, Higuera ES, Valder CR, Song YH, Svensson CI, Myers RR. Injury type-specific calcium channel alpha 2 delta-1 subunit up-regulation in rat neuropathic pain models correlates with antiallodynic effects of gabapentin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:1199–1205. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.041574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies A, Hendrich J, Van Minh AT, Wratten J, Douglas L, Dolphin AC. Functional biology of the alpha(2)delta subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heblich F, Tran Van Minh A, Hendrich J, Watschinger K, Dolphin AC. Time course and specificity of the pharmacological disruption of the trafficking of voltage-gated calcium channels by gabapentin. Channels (Austin) 2008;2:4–9. doi: 10.4161/chan.2.1.6045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hendrich J, Van Minh AT, Heblich F, Nieto-Rostro M, Watschinger K, Striessnig J, Wratten J, Davies A, Dolphin AC. Pharmacological disruption of calcium channel trafficking by the alpha2delta ligand gabapentin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3628–3633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708930105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mich PM, Horne WA. Alternative splicing of the Ca2+ channel beta4 subunit confers specificity for gabapentin inhibition of Cav2.1 trafficking. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:904–912. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.045153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coderre TJ, Kumar N, Lefebvre CD, Yu JS. Evidence that gabapentin reduces neuropathic pain by inhibiting the spinal release of glutamate. J Neurochem. 2005;94:1131–1139. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimoyama M, Shimoyama N, Hori Y. Gabapentin affects glutamatergic excitatory neurotransmission in the rat dorsal horn. Pain. 2000;85:405–414. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00283-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayashida K, Obata H, Nakajima K, Eisenach JC. Gabapentin acts within the locus coeruleus to alleviate neuropathic pain. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:1077–1084. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31818dac9c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor CP, Gee NS, Su TZ, Kocsis JD, Welty DF, Brown JP, Dooley DJ, Boden P, Singh L. A summary of mechanistic hypotheses of gabapentin pharmacology. Epilepsy Res. 1998;29:233–249. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(97)00084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petroff OA, Rothman DL, Behar KL, Lamoureux D, Mattson RH. The effect of gabapentin on brain gamma-aminobutyric acid in patients with epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:95–99. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gotz E, Feuerstein TJ, Lais A, Meyer DK. Effects of gabapentin on release of gamma-aminobutyric acid from slices of rat neostriatum. Arzneimittelforschung. 1993;43:636–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brawek B, Loffler M, Weyerbrock A, Feuerstein TJ. Effects of gabapentin and pregabalin on K+-evoked 3H-GABA and 3H-glutamate release from human neocortical synaptosomes. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2009;379:361–369. doi: 10.1007/s00210-008-0370-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takasu K, Ono H, Tanabe M. Gabapentin produces PKA-dependent pre-synaptic inhibition of GABAergic synaptic transmission in LC neurons following partial nerve injury in mice. J Neurochem. 2008;105:933–942. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim SH, Chung JM. An experimental model for peripheral neuropathy produced by segmental spinal nerve ligation in the rat. Pain. 1992;50:355–363. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. San Diego: Academic Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayashida K, Eisenach JC. Spinal alpha 2-adrenoceptor-mediated analgesia in neuropathic pain reflects brain-derived nerve growth factor and changes in spinal cholinergic neuronal function. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:406–412. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181de6d2c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Majumdar S, Mallick BN. Increased levels of tyrosine hydroxylase and glutamic acid decarboxylase in locus coeruleus neurons after rapid eye movement sleep deprivation in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2003;338:193–196. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)01404-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanaka D, Asakura M, Kanai S, Hishinuma T, Fujii S, Nagashima H. Regulation of TH activity by GAD immunoreactivity in rat peri-LC after chronic variable stress. Nihon Shinkei Seishin Yakurigaku Zasshi. 2005;25:11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elizalde N, Garcia-Garcia AL, Totterdell S, Gendive N, Venzala E, Ramirez MJ, Del Rio J, Tordera RM. Sustained stress-induced changes in mice as a model for chronic depression. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;210:393–406. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1835-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raudensky J, Yamamoto BK. Effects of chronic unpredictable stress and methamphetamine on hippocampal glutamate function. Brain Res. 2007;1135:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gruen RJ, Wenberg K, Elahi R, Friedhoff AJ. Alterations in GABAA receptor binding in the prefrontal cortex following exposure to chronic stress. Brain Res. 1995;684:112–114. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00441-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montpied P, Weizman A, Weizman R, Kook KA, Morrow AL, Paul SM. Repeated swim-stress reduces GABAA receptor alpha subunit mRNAs in the mouse hippocampus. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1993;18:267–272. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(93)90199-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gwak YS, Hulsebosch CE. GABA and central neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:799–808. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gwak YS, Crown ED, Unabia GC, Hulsebosch CE. Propentofylline attenuates allodynia, glial activation and modulates GABAergic tone after spinal cord injury in the rat. Pain. 2008;138:410–422. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu J, Wolfe D, Hao S, Huang S, Glorioso JC, Mata M, Fink DJ. Peripherally delivered glutamic acid decarboxylase gene therapy for spinal cord injury pain. Mol Ther. 2004;10:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eaton MJ, Plunkett JA, Karmally S, Martinez MA, Montanez K. Changes in GAD- and GABA- immunoreactivity in the spinal dorsal horn after peripheral nerve injury and promotion of recovery by lumbar transplant of immortalized serotonergic precursors. J Chem Neuroanat. 1998;16:57–72. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(98)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Honmou O, Oyelese AA, Kocsis JD. The anticonvulsant gabapentin enhances promoted release of GABA in hippocampus: a field potential analysis. Brain Res. 1995;692:273–277. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00634-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Timmerman W, Bouma M, De Vries JB, Davis M, Westerink BH. A microdialysis study on the mechanism of action of gabapentin. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;398:53–57. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00309-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Hooft JA, Dougherty JJ, Endeman D, Nichols RA, Wadman WJ. Gabapentin inhibits presynaptic Ca(2+) influx and synaptic transmission in rat hippocampus and neocortex. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;449:221–228. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayashida KI, Clayton BA, Johnson JE, Eisenach JC. Brain derived nerve growth factor induces spinal noradrenergic fiber sprouting and enhances clonidine analgesia following nerve injury in rats. Pain. 2008;136:348–355. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gassner M, Ruscheweyh R, Sandkuhler J. Direct excitation of spinal GABAergic interneurons by noradrenaline. Pain. 2009;145:204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baba H, Shimoji K, Yoshimura M. Norepinephrine facilitates inhibitory transmission in substantia gelatinosa of adult rat spinal cord (part 1): Effects on axon terminals of GABAergic and glycinergic neurons. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:473–484. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200002000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hwang JH, Yaksh TL. Effect of subarachnoid gabapentin on tactile-evoked allodynia in a surgically induced neuropathic pain model in the rat. Reg Anesth. 1997;22:249–256. doi: 10.1016/s1098-7339(06)80010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]